Metastases to the gallbladder (GB) are very rare. Malignant melanoma is their most common origin.1 We report the case of a patient with a history of melanoma and pathological uptake in the GB seen on positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT). Surgery was performed with the preoperative diagnosis of melanoma metastasis to the GB, but the final histology was unexpected.

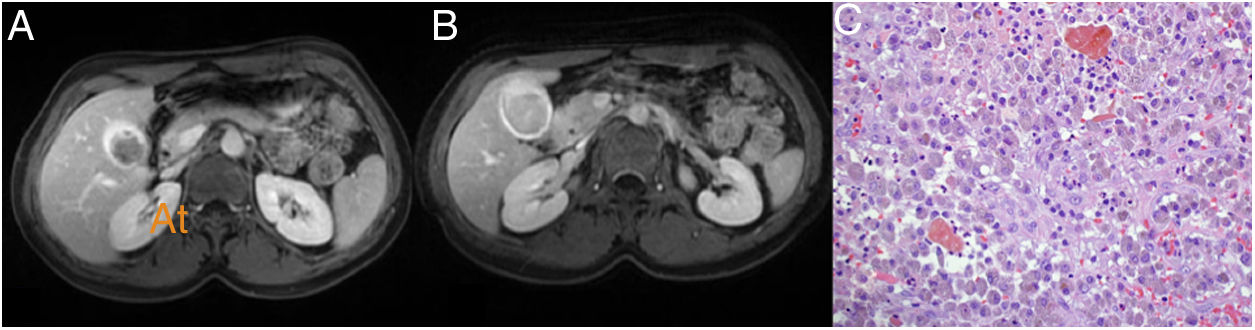

The patient was a 38-year-old woman diagnosed in August 2015 with malignant melanoma on her back. She was treated with wide resection and sentinel node biopsy (Breslow: 2 mm, Clark: III, without ulceration, mitosis: <1/mm2, stage Ib: pT2aN0M0). In September 2018, left axillary lymphadenopathy was detected by self-palpation; fine needle aspiration (FNA) was performed and confirmed melanoma metastasis. A left axillary lymphadenectomy was performed with tumour infiltration in four of the 14 lymph nodes removed. The patient received radiotherapy to the left axilla (50 Gy). In January 2019, she started treatment with nivolumab. In January 2020, a PET/CT scan revealed a 23-mm hypermetabolic lesion in the hepatic hilum (standardised uptake value [SUV]: 9.3), which was causing dilation of the GB. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a polypoid mass in the GB, with a diameter of 23 mm, hypointense on T1, and hyperintense and inhomogeneous on T2; these findings were consistent with gallbladder cancer (GBC) or metastasis. The gallbladder content was hyperintense on T1 and hypointense on T2, consistent with haemorrhagic content (Fig. 1A and B). All laboratory tests were normal. The multidisciplinary oncology committee decided on surgery.

The procedure revealed a dilated GB with a thickened wall and inflammation of the hilar plate. A cholecystectomy plus a 1.5-cm resection of the liver parenchyma was performed to ensure a clear margin. Histological sections showed lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate in the wall of the GB, accompanied by abundant histiocytes, which contained brown pigment in their cytoplasm and formed nodules (Fig. 1C). Erosions and ulcers of the mucosa were observed, with a significant acute inflammatory component forming abscesses. In the histological and immunohistochemical studies, no tumour infiltration was observed. The final histological diagnosis was xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis (XGC).

Malignant melanoma is one of the most aggressive forms of skin cancer. PET/CT has a high precision for the detection of metastases in malignant melanoma, but there is very little experience with using PET/CT in GB metastases.1

XGC is a relatively uncommon benign inflammatory disease of the GB (1.3%–5.2% of GBs removed) that occurs predominantly in middle-aged and elderly people.2,3 Its pathogenesis remains unclear, but it is most widely accepted that after an inflammatory process and a granulomatous reaction, extravasation of bile into the GB wall occurs.2,3 This focal or diffuse inflammatory process causes a macroscopic thickening of the GB wall similar to a neoplasm.2,3 The clinical signs of XGC are those seen in acute/chronic cholecystitis, but some patients are asymptomatic, as occurred in our patient. It is difficult to distinguish between GBC and XGC by imaging techniques, which may lead to unnecessary liver resections with higher morbidity than cholecystectomy.2,3

PET/CT is not entirely specific for malignant GB lesions.2 A 2015 meta-analysis of PET in GBC found a sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 78%. There were only 22 false positives which occurred in benign inflammatory lesions such as XGC, tuberculosis, adenomyomatosis or acute cholecystitis, and they occur due to absorption of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) in inflammatory cells.2–4 Nishiyama et al. evaluated the correlation between CRP and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) levels in the GB and verified that the specificity of PET for the diagnosis of GBC is 80% if CRP is normal, but 0% if CRP is elevated.5 However, our patient had normal CRP levels when PET was performed.

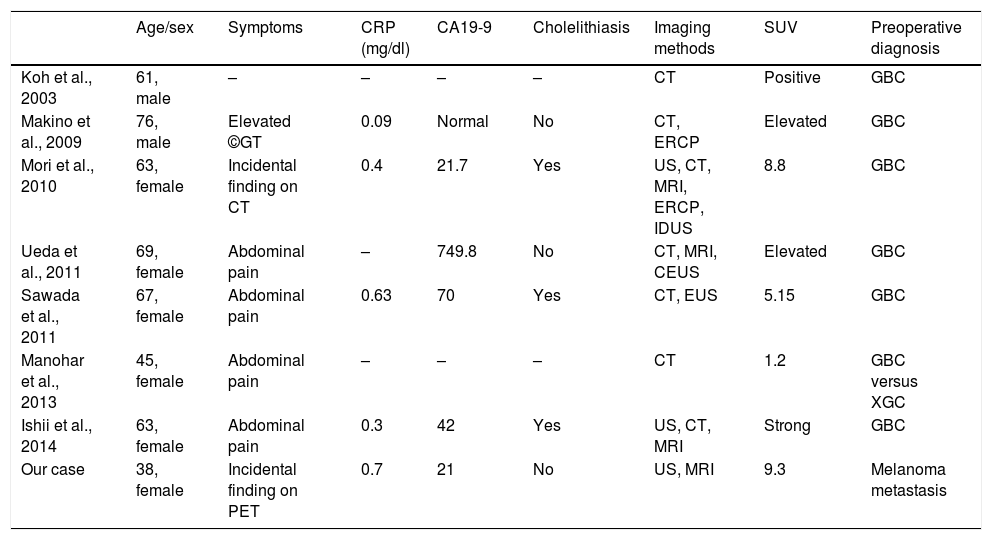

The eight published cases of false positive PET in XGC, including our case, do not allow many conclusions to be drawn. Six were women and two were men. The mean age was 60 years (range: 38–76). Four presented abdominal pain and three were incidental findings. CRP was always normal; inconsistent with the findings of Nishiyama et al.;5 three presented elevated carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) and only 50% (4/8) had cholelithiasis preoperatively. The PET SUV was high in all cases except one. In the seven previous cases, the usual preoperative diagnosis was GBC (Table 1).

Published cases of false positive PET in XGC.

| Age/sex | Symptoms | CRP (mg/dl) | CA19-9 | Cholelithiasis | Imaging methods | SUV | Preoperative diagnosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koh et al., 2003 | 61, male | – | – | – | – | CT | Positive | GBC |

| Makino et al., 2009 | 76, male | Elevated ©GT | 0.09 | Normal | No | CT, ERCP | Elevated | GBC |

| Mori et al., 2010 | 63, female | Incidental finding on CT | 0.4 | 21.7 | Yes | US, CT, MRI, ERCP, IDUS | 8.8 | GBC |

| Ueda et al., 2011 | 69, female | Abdominal pain | – | 749.8 | No | CT, MRI, CEUS | Elevated | GBC |

| Sawada et al., 2011 | 67, female | Abdominal pain | 0.63 | 70 | Yes | CT, EUS | 5.15 | GBC |

| Manohar et al., 2013 | 45, female | Abdominal pain | – | – | – | CT | 1.2 | GBC versus XGC |

| Ishii et al., 2014 | 63, female | Abdominal pain | 0.3 | 42 | Yes | US, CT, MRI | Strong | GBC |

| Our case | 38, female | Incidental finding on PET | 0.7 | 21 | No | US, MRI | 9.3 | Melanoma metastasis |

CEUS: contrast-enhanced ultrasound; CRP: C-reactive protein; CT: computed tomography; ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EUS: endoscopic ultrasound; GBC: gallbladder cancer; IDUS: intraductal ultrasound; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PET: positron emission tomography; US: abdominal ultrasound; XGC: xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis.

In conclusion, preoperative diagnosis of XGC is complex even when several imaging and PET techniques are performed. In our case, the patient's previous diagnosis of melanoma led us to a misdiagnosis of metastasis to the GB.

Please cite this article as: Ramia JM, Garcia Gil JM, Manuel-Vazquez A, Latorre-Fragua R, Candia A, de la Plaza-Llamas R. Colecistitis xantogranulomatosa como causa de falso positivo en PET. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;45:60–61.