Granulocyte and monocyte apheresis is the main non-pharmacological treatment for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), but we do not know how well accepted it is by patients in our setting.

AimTo determine how granulocyte and monocyte apheresis is perceived by patients in clinical practice in Spain.

MethodsOutpatients treated with granulocyte and monocyte apheresis in five IBD Units in Spain were asked to fill in a 14-item questionnaire.

ResultsFifty-two patients completed the questionnaire (88% ulcerative colitis, 12% Crohn's disease; 44% female; age 35 years [IQR 23–51]). Granulocyte and monocyte apheresis was generally well tolerated and well accepted. Very few of the participants regarded the length of the sessions as a limitation. The gastrointestinal symptoms, however, were a frequent concern, both in terms of attending to receive treatment and during the sessions. Overall, 44% were satisfied with the treatment effectiveness. Sixty percent (60%) claimed to be satisfied with the therapy overall, but this was influenced by the patients’ clinical response to the therapy. Eighty-two percent (82%) of participants said they would agree to be treated with this technique again in the future, regardless of the response to the treatment.

ConclusionsGranulocyte and monocyte apheresis is well tolerated and accepted by patients with IBD. Although we found no significant differences according to type of IBD or apheresis regimen, patient perception was affected by clinical effectiveness.

La leucocitoaféresis constituye el principal tratamiento no farmacológico para la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII), pero no conocemos su grado de aceptación por los pacientes en nuestro entorno.

ObjetivoConocer la percepción de los pacientes sobre la leucocitoaféresis en la práctica clínica en España.

MétodosSe ofreció un cuestionario de 14 preguntas a los pacientes ambulatorios tratados con leucocitoaféresis en 5 unidades de EII en España.

ResultadosCincuenta y dos pacientes respondieron el cuestionario (88% colitis ulcerosa, 12% enfermedad de Crohn; 44% mujeres, 35 años [RIQ: 23-51]). La leucocitoaféresis fue bien tolerada de forma global y con un alto grado de aceptación. La mayoría de pacientes no percibía la duración de las sesiones como una limitación. En cambio, los síntomas digestivos eran una preocupación habitual, tanto para acudir al tratamiento como durante las sesiones. Un 44% estaban satisfechos con la efectividad del tratamiento. El 60% contestaron que estaban satisfechos con la técnica de forma global, pero esto estaba influenciado por la respuesta clínica que habían experimentado. Un 82% estarían dispuestos a ser tratados de nuevo con la técnica, independientemente de la respuesta al tratamiento.

ConclusionesLa leucocitoaféresis es una técnica bien tolerada y aceptada por los pacientes con EII. A pesar de que no encontramos diferencias según el tipo de EII o la pauta de tratamiento, sí encontramos una percepción diferente según la efectividad de la técnica.

Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD) are two chronic conditions of the gastrointestinal tract, and both are included in the spectrum of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The treatment for these two diseases usually includes the use of drugs targeting the multiple immune mechanisms involved in their pathogenesis. Thus immunomodulators and biologic drugs are frequently required in clinical practice, but granulocyte–monocyte apheresis (GMA) has emerged as an alternative non-pharmacological option in some cases. This technique benefits from the ability of a column, filled with around 35,000 cellulose acetate beads, to adsorb some complement factors, white blood cells and platelets.1 Heparin-anticoagulated whole blood is extracted and processed through the column and later re-infused in a contralateral vein. The standard treatment consists of five weekly sessions of 60min processing 1800ml of blood, but it has been described that increasing the number of sessions with a longer duration may achieve better results in terms of clinical response.2,3

Recently, evidence has been emerging to suggest that there is a gap between the perceptions of patients with IBD and healthcare professionals.4 Only one previous study, of 112 patients from a single-centre in Japan, has explored in detail the experience and satisfaction of patients treated with GMA.5 In that cohort, 57% felt that coming to the hospital for GMA was somewhat inconvenient. Interestingly, 59% felt some burden during GMA sessions, and the main reason was the fear of faecal urgency during the treatment. Nevertheless, most of the patients (88%) were satisfied with the technique, and almost three-quarters were willing to be treated again with this therapy. The aim of our study was to assess the perceptions and satisfaction of patients with GMA in the European population in our daily practice.

Material and methodsWe have designed and used a new 14-item questionnaire assessing the experience of patients with GMA (Appendix A). In particular, it includes questions about the effort of going to the hospital, the time it takes to receive the treatment, discomfort associated with the use of needles, their greatest source of concern during the sessions, their opinion about the effectiveness of the therapy, and whether they would be willing to receive it again in the future. All patients were treated with GMA in one of five IBD units in Spain, and all completed their treatment regimen with GMA as prescribed by their treating physician in routine clinical practice.

Data on clinical characteristics were extracted from patients’ medical records retrospectively. We collected data on the following set of variables: age, sex, IBD type, disease extent according to the Montreal classification, and previous treatments including surgery. The clinical effectiveness of the treatment was assessed with the Mayo Score for UC and the Harvey–Bradshaw Index for CD.6,7 Data were collected retrospectively to assess the disease activity scores and biomarkers at baseline and 1 month after the last session when available. The Local Ethics Committee (Basque Country, Spain) approved the study protocol.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics of sociodemographic, questionnaire and clinical data were calculated using means and standard deviations (SDs) for quantitative data and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Relationships between IBD subtype, regimen, response, number of sessions and other sociodemographic, clinical and questionnaire variables were assessed with Chi-square and Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon and Kruskal–Wallis tests for quantitative variables. Differences were deemed statistically significant at p<0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS System, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Carey, NC).

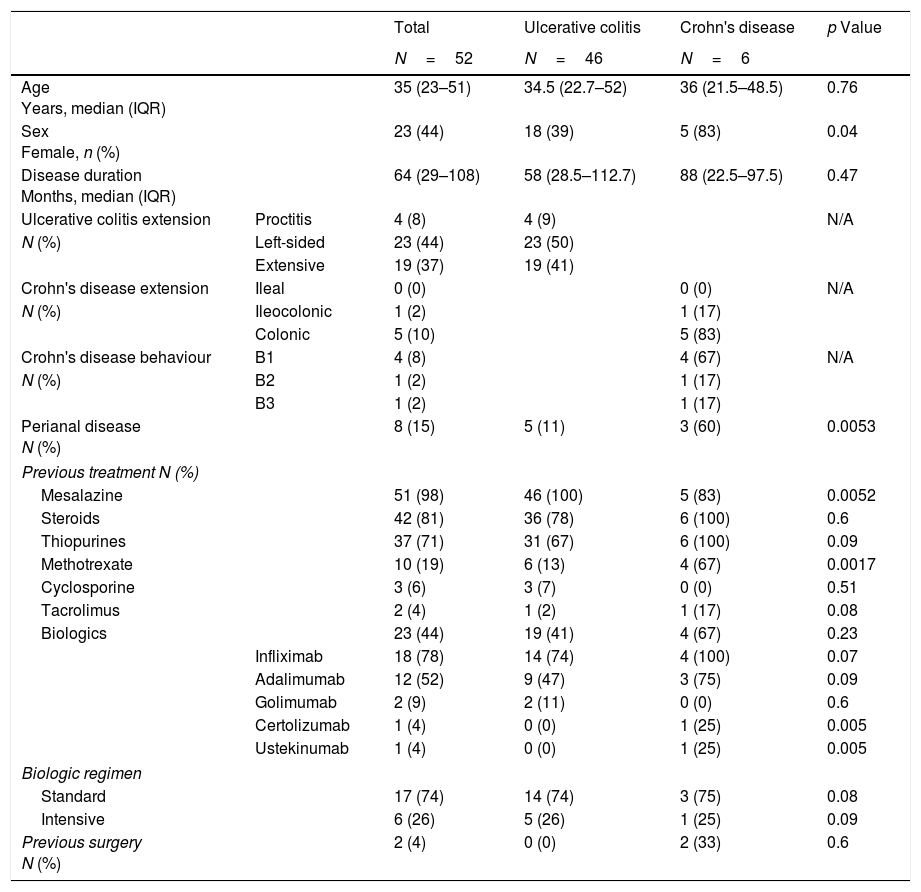

ResultsA total of 52 patients with IBD were included. The characteristics of the cohort are summarised in Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Total | Ulcerative colitis | Crohn's disease | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=52 | N=46 | N=6 | |||

| Age Years, median (IQR) | 35 (23–51) | 34.5 (22.7–52) | 36 (21.5–48.5) | 0.76 | |

| Sex Female, n (%) | 23 (44) | 18 (39) | 5 (83) | 0.04 | |

| Disease duration Months, median (IQR) | 64 (29–108) | 58 (28.5–112.7) | 88 (22.5–97.5) | 0.47 | |

| Ulcerative colitis extension | Proctitis | 4 (8) | 4 (9) | N/A | |

| N (%) | Left-sided | 23 (44) | 23 (50) | ||

| Extensive | 19 (37) | 19 (41) | |||

| Crohn's disease extension | Ileal | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A | |

| N (%) | Ileocolonic | 1 (2) | 1 (17) | ||

| Colonic | 5 (10) | 5 (83) | |||

| Crohn's disease behaviour | B1 | 4 (8) | 4 (67) | N/A | |

| N (%) | B2 | 1 (2) | 1 (17) | ||

| B3 | 1 (2) | 1 (17) | |||

| Perianal disease N (%) | 8 (15) | 5 (11) | 3 (60) | 0.0053 | |

| Previous treatment N (%) | |||||

| Mesalazine | 51 (98) | 46 (100) | 5 (83) | 0.0052 | |

| Steroids | 42 (81) | 36 (78) | 6 (100) | 0.6 | |

| Thiopurines | 37 (71) | 31 (67) | 6 (100) | 0.09 | |

| Methotrexate | 10 (19) | 6 (13) | 4 (67) | 0.0017 | |

| Cyclosporine | 3 (6) | 3 (7) | 0 (0) | 0.51 | |

| Tacrolimus | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | 1 (17) | 0.08 | |

| Biologics | 23 (44) | 19 (41) | 4 (67) | 0.23 | |

| Infliximab | 18 (78) | 14 (74) | 4 (100) | 0.07 | |

| Adalimumab | 12 (52) | 9 (47) | 3 (75) | 0.09 | |

| Golimumab | 2 (9) | 2 (11) | 0 (0) | 0.6 | |

| Certolizumab | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 0.005 | |

| Ustekinumab | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 0.005 | |

| Biologic regimen | |||||

| Standard | 17 (74) | 14 (74) | 3 (75) | 0.08 | |

| Intensive | 6 (26) | 5 (26) | 1 (25) | 0.09 | |

| Previous surgery N (%) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (33) | 0.6 | |

IQR: interquartile range.

All patients were treated with the same apheresis device (Adacolumn®, Japan Immunoresearch Laboratories, JIMRO, Takasaki, Japan). One of two different GMA regimens was prescribed as judged appropriate by each treating physician at each centre. The standard treatment regimen involves the use of five weekly sessions processing 1800ml per session in 60min. Alternatively, the treatment can be more intensive, patients usually receiving two sessions per week, with the aim of recirculating 100% of patients’ extracellular fluid volume per session, in approximately 90min, in line with the intensive regimen described elsewhere.8,9 In our cohort, half of the patients were treated with each regimen. Those assigned to the traditional regimen underwent a mean of 5 sessions (SD 1.9) and those on the intensive regimen 9 (SD 2.3) (p<0.0001).

One month after finishing the technique, the clinical activity scores in UC and CD patients decreased, but these differences were only significant for the former [4.9 (SD 2.2) versus 3.7 (SD 2.3), p=0.004; 9.7 (SD 4.3) versus 7.7 (SD 6.1), p=0.5, respectively] (Appendix A). The overall response rate to the technique was 67%, being the same for UC and CD (67%), but the remission rates were slightly higher in patients with UC than those with CD (33% and 25%, respectively, p=0.73). Twenty-four percent of patients were able to be completely weaned off steroids 1 month after finishing the apheresis, notably all these patients had UC. The biomarkers and disease activity scores are summarised in the supplementary material (Appendix A).

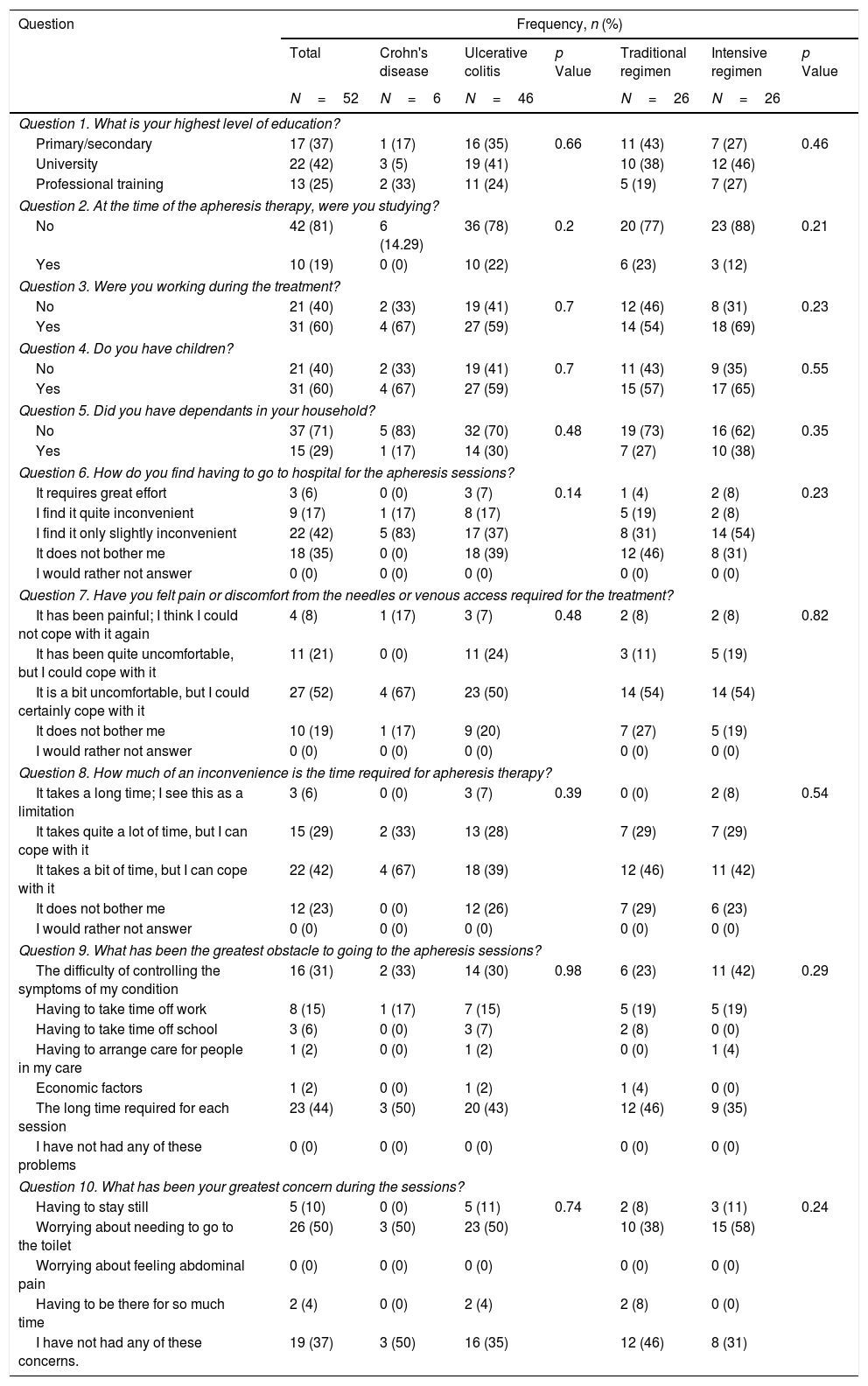

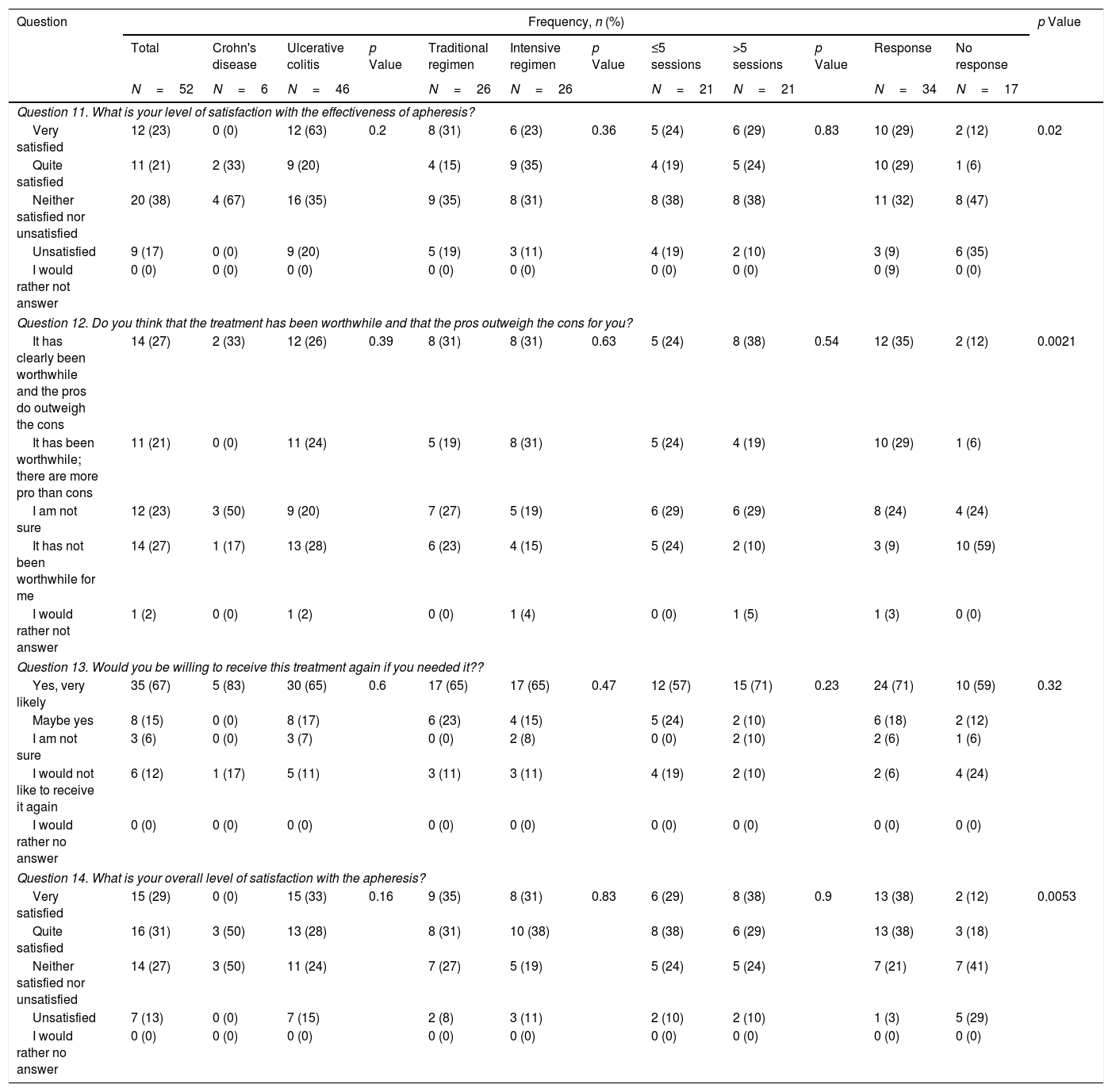

Questionnaire assessmentFifty-two patients completed the questionnaire. The results are summarised in Tables 2 and 3, showing overall response rates and stratified by disease type, GMA regimen, number of sessions and whether there was a clinical response to the technique.

Questionnaire results.

| Question | Frequency, n (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | p Value | Traditional regimen | Intensive regimen | p Value | |

| N=52 | N=6 | N=46 | N=26 | N=26 | |||

| Question 1. What is your highest level of education? | |||||||

| Primary/secondary | 17 (37) | 1 (17) | 16 (35) | 0.66 | 11 (43) | 7 (27) | 0.46 |

| University | 22 (42) | 3 (5) | 19 (41) | 10 (38) | 12 (46) | ||

| Professional training | 13 (25) | 2 (33) | 11 (24) | 5 (19) | 7 (27) | ||

| Question 2. At the time of the apheresis therapy, were you studying? | |||||||

| No | 42 (81) | 6 (14.29) | 36 (78) | 0.2 | 20 (77) | 23 (88) | 0.21 |

| Yes | 10 (19) | 0 (0) | 10 (22) | 6 (23) | 3 (12) | ||

| Question 3. Were you working during the treatment? | |||||||

| No | 21 (40) | 2 (33) | 19 (41) | 0.7 | 12 (46) | 8 (31) | 0.23 |

| Yes | 31 (60) | 4 (67) | 27 (59) | 14 (54) | 18 (69) | ||

| Question 4. Do you have children? | |||||||

| No | 21 (40) | 2 (33) | 19 (41) | 0.7 | 11 (43) | 9 (35) | 0.55 |

| Yes | 31 (60) | 4 (67) | 27 (59) | 15 (57) | 17 (65) | ||

| Question 5. Did you have dependants in your household? | |||||||

| No | 37 (71) | 5 (83) | 32 (70) | 0.48 | 19 (73) | 16 (62) | 0.35 |

| Yes | 15 (29) | 1 (17) | 14 (30) | 7 (27) | 10 (38) | ||

| Question 6. How do you find having to go to hospital for the apheresis sessions? | |||||||

| It requires great effort | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | 3 (7) | 0.14 | 1 (4) | 2 (8) | 0.23 |

| I find it quite inconvenient | 9 (17) | 1 (17) | 8 (17) | 5 (19) | 2 (8) | ||

| I find it only slightly inconvenient | 22 (42) | 5 (83) | 17 (37) | 8 (31) | 14 (54) | ||

| It does not bother me | 18 (35) | 0 (0) | 18 (39) | 12 (46) | 8 (31) | ||

| I would rather not answer | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Question 7. Have you felt pain or discomfort from the needles or venous access required for the treatment? | |||||||

| It has been painful; I think I could not cope with it again | 4 (8) | 1 (17) | 3 (7) | 0.48 | 2 (8) | 2 (8) | 0.82 |

| It has been quite uncomfortable, but I could cope with it | 11 (21) | 0 (0) | 11 (24) | 3 (11) | 5 (19) | ||

| It is a bit uncomfortable, but I could certainly cope with it | 27 (52) | 4 (67) | 23 (50) | 14 (54) | 14 (54) | ||

| It does not bother me | 10 (19) | 1 (17) | 9 (20) | 7 (27) | 5 (19) | ||

| I would rather not answer | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Question 8. How much of an inconvenience is the time required for apheresis therapy? | |||||||

| It takes a long time; I see this as a limitation | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | 3 (7) | 0.39 | 0 (0) | 2 (8) | 0.54 |

| It takes quite a lot of time, but I can cope with it | 15 (29) | 2 (33) | 13 (28) | 7 (29) | 7 (29) | ||

| It takes a bit of time, but I can cope with it | 22 (42) | 4 (67) | 18 (39) | 12 (46) | 11 (42) | ||

| It does not bother me | 12 (23) | 0 (0) | 12 (26) | 7 (29) | 6 (23) | ||

| I would rather not answer | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Question 9. What has been the greatest obstacle to going to the apheresis sessions? | |||||||

| The difficulty of controlling the symptoms of my condition | 16 (31) | 2 (33) | 14 (30) | 0.98 | 6 (23) | 11 (42) | 0.29 |

| Having to take time off work | 8 (15) | 1 (17) | 7 (15) | 5 (19) | 5 (19) | ||

| Having to take time off school | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | 3 (7) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | ||

| Having to arrange care for people in my care | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | ||

| Economic factors | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | ||

| The long time required for each session | 23 (44) | 3 (50) | 20 (43) | 12 (46) | 9 (35) | ||

| I have not had any of these problems | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Question 10. What has been your greatest concern during the sessions? | |||||||

| Having to stay still | 5 (10) | 0 (0) | 5 (11) | 0.74 | 2 (8) | 3 (11) | 0.24 |

| Worrying about needing to go to the toilet | 26 (50) | 3 (50) | 23 (50) | 10 (38) | 15 (58) | ||

| Worrying about feeling abdominal pain | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Having to be there for so much time | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | ||

| I have not had any of these concerns. | 19 (37) | 3 (50) | 16 (35) | 12 (46) | 8 (31) | ||

Questionnaire results about satisfaction with granulocyte–monocyte apheresis.

| Question | Frequency, n (%) | p Value | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | p Value | Traditional regimen | Intensive regimen | p Value | ≤5 sessions | >5 sessions | p Value | Response | No response | ||

| N=52 | N=6 | N=46 | N=26 | N=26 | N=21 | N=21 | N=34 | N=17 | |||||

| Question 11. What is your level of satisfaction with the effectiveness of apheresis? | |||||||||||||

| Very satisfied | 12 (23) | 0 (0) | 12 (63) | 0.2 | 8 (31) | 6 (23) | 0.36 | 5 (24) | 6 (29) | 0.83 | 10 (29) | 2 (12) | 0.02 |

| Quite satisfied | 11 (21) | 2 (33) | 9 (20) | 4 (15) | 9 (35) | 4 (19) | 5 (24) | 10 (29) | 1 (6) | ||||

| Neither satisfied nor unsatisfied | 20 (38) | 4 (67) | 16 (35) | 9 (35) | 8 (31) | 8 (38) | 8 (38) | 11 (32) | 8 (47) | ||||

| Unsatisfied | 9 (17) | 0 (0) | 9 (20) | 5 (19) | 3 (11) | 4 (19) | 2 (10) | 3 (9) | 6 (35) | ||||

| I would rather not answer | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (9) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Question 12. Do you think that the treatment has been worthwhile and that the pros outweigh the cons for you? | |||||||||||||

| It has clearly been worthwhile and the pros do outweigh the cons | 14 (27) | 2 (33) | 12 (26) | 0.39 | 8 (31) | 8 (31) | 0.63 | 5 (24) | 8 (38) | 0.54 | 12 (35) | 2 (12) | 0.0021 |

| It has been worthwhile; there are more pro than cons | 11 (21) | 0 (0) | 11 (24) | 5 (19) | 8 (31) | 5 (24) | 4 (19) | 10 (29) | 1 (6) | ||||

| I am not sure | 12 (23) | 3 (50) | 9 (20) | 7 (27) | 5 (19) | 6 (29) | 6 (29) | 8 (24) | 4 (24) | ||||

| It has not been worthwhile for me | 14 (27) | 1 (17) | 13 (28) | 6 (23) | 4 (15) | 5 (24) | 2 (10) | 3 (9) | 10 (59) | ||||

| I would rather not answer | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Question 13. Would you be willing to receive this treatment again if you needed it?? | |||||||||||||

| Yes, very likely | 35 (67) | 5 (83) | 30 (65) | 0.6 | 17 (65) | 17 (65) | 0.47 | 12 (57) | 15 (71) | 0.23 | 24 (71) | 10 (59) | 0.32 |

| Maybe yes | 8 (15) | 0 (0) | 8 (17) | 6 (23) | 4 (15) | 5 (24) | 2 (10) | 6 (18) | 2 (12) | ||||

| I am not sure | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | 3 (7) | 0 (0) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 2 (6) | 1 (6) | ||||

| I would not like to receive it again | 6 (12) | 1 (17) | 5 (11) | 3 (11) | 3 (11) | 4 (19) | 2 (10) | 2 (6) | 4 (24) | ||||

| I would rather no answer | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Question 14. What is your overall level of satisfaction with the apheresis? | |||||||||||||

| Very satisfied | 15 (29) | 0 (0) | 15 (33) | 0.16 | 9 (35) | 8 (31) | 0.83 | 6 (29) | 8 (38) | 0.9 | 13 (38) | 2 (12) | 0.0053 |

| Quite satisfied | 16 (31) | 3 (50) | 13 (28) | 8 (31) | 10 (38) | 8 (38) | 6 (29) | 13 (38) | 3 (18) | ||||

| Neither satisfied nor unsatisfied | 14 (27) | 3 (50) | 11 (24) | 7 (27) | 5 (19) | 5 (24) | 5 (24) | 7 (21) | 7 (41) | ||||

| Unsatisfied | 7 (13) | 0 (0) | 7 (15) | 2 (8) | 3 (11) | 2 (10) | 2 (10) | 1 (3) | 5 (29) | ||||

| I would rather no answer | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||

First of all, we performed an analysis of the responses in the whole cohort. GMA was well tolerated by the patients, with 77% of them reporting that receiving the treatment at the hospital was no bother to them or only slightly inconvenient, with 8% of participants considering the use of needles an important issue that could preclude the use of the therapy (question [Q] 6 and 7). Related to the time spent in each session, almost all of the patients (94%) did not consider this as a limitation (Q8). Nevertheless, among all the possible problems that were assessed, the time spent in each visit was the option most frequently chosen by patients (44%) (Q9). An important finding is that the second most common obstacle to attending the sessions was the difficulty of controlling symptoms of the disease (31%) (Q9). The importance of this concern is underlined by the fact that it was also the most frequently cited problem during the sessions (50%) (Q10). Regarding satisfaction with the technique (Table 3), we found that 44% of patients were satisfied with the effectiveness of GMA (Q11), and a similar percentage (48%) considered that the advantages outweigh the disadvantages of the therapy, while 27% answered that it was not worth receiving the treatment (Q12). We also assessed whether the patients would be willing to be treated again with this technique. Eighty-two percent of patients indicated that they would agree to receive GMA in the future, with a small percentage (12%) answering that they would decline this therapy at a later stage (Q13). When asked to rate their experience with GMA, 60% of patients were satisfied, while only 13% were not (Q14).

The questionnaire responses were analysed further to assess whether any characteristics of the treatment were related to a different perception of GMA. We found no statistically significant differences in any of the answers as a function of disease type, GMA regimen or total number of sessions received. On the other hand, a slightly higher percentage of patients in the intensive treatment reported some degree of inconvenience or effort related to coming to the hospital (70% versus 54%, p=0.23). Regarding the main obstacles to attending the sessions, in the intensive GMA group, we found that uncontrolled symptoms of the disease (42%) were the most frequent concern, while a significant proportion of patients on both regimens indicated that the time required to attend treatment sessions was an important limitation (46% and 35% of those receiving the standard and intensive regimens, respectively, p=0.29). During the sessions, needing to go to the toilet was the main concern of both standard and intensive group patients (38% and 58%, respectively, p=0.24).

Regarding satisfaction with the effectiveness of the treatment, there was not a significant difference between patients on the standard and intensive regimes, with around 50% being satisfied or very satisfied and less than 20% unsatisfied in both cases (p=0.36). These results were closely associated with whether GMA had been clinically effective, as demonstrated by the different levels of satisfaction between those who did and did not respond to the treatment (58% versus 18%, respectively, p=0.02). These statistically significant different points of view were also reflected in patients’ responses when asked about the balance between the advantages and disadvantages of GMA, more responders considering that the pros outweighed the cons (64% versus 18%, p=0.0021). Although 60% of the whole cohort reported being overall satisfied with the treatment, there were also significant differences when the answers were assessed according to clinical effectiveness (76% versus 30% in responders and non-responders, respectively, p=0.0053). Even more importantly, however, when patients were asked about their willingness to be treated again with GMA, most said they would consider it, regardless of whether the treatment had been effective on this occasion (89% versus 71% in responders and non-responders, respectively, p=0.32).

Adverse eventsSix adverse events (12%) were recorded. Headache occurred in four patients and fever in two. All these events were considered mild to moderate, and none of the patients required hospitalisation due to these symptoms. There were no cases of local or systemic infection during the treatment. No adverse events lead to discontinuation of the technique.

DiscussionIn this study, we describe for the first time the perception of European patients of GMA in our setting and across multiple hospitals. We have found that this technique is well accepted and tolerated and that the main problems in receiving the treatment are the symptoms of the disease itself and the time required for the sessions. Nevertheless, a high proportion of patients are satisfied and willing to be treated again with GMA.

The treatment of IBD has evolved in recent years with a significant increase in the number of pharmacological options available. Biologics have demonstrated to be effective in the induction of remission, especially in combination with thiopurines.10,11 Although they have changed dramatically the management of IBD, there is a significant number of patients who do not show a response or, once a response is achieved, lose it.12 Moreover, biological drugs may be contraindicated in some patients with specific coexisting conditions. This underlines the great need for other treatment options, while it is expected that new drugs will become available in the coming years.13

GMA has been established as the main non-pharmacological option for IBD. This approach consists in the recirculation of the patients’ blood through a membrane with cellulose acetate beads.1,14 This adsorbs multiple cellular and humoral inflammatory mediators involved in the pathogenesis of IBD.15 The effectiveness of GMA is supported by the data obtained from real-world studies16,17 and clinical trials,18,19 especially in UC patients. With the increasing therapeutic options for IBD, physicians should be able to make decisions based on the efficacy of each treatment, the natural history of the disease and previous medications, along with the sociodemographic situation of each individual patient. In this context, patients should also be part of a shared decision-making process.20 This becomes even more important when an international study showed that up to half of the patients with moderate-to-severe UC are dissatisfied with their treatments.21 These findings may well be attributable to different perceptions of the current treatment of IBD, doctors seeming to be more concerned about objective measures of remission, while patients usually focus on quality of life and social outcomes of treatment.22

Related to GMA, there is only one previous report assessing patients’ perceptions of the procedure.5 In that study, 112 patients were asked about the inconvenience of visiting the hospital, the use of needles, the time spent on the sessions and their satisfaction with the safety and effectiveness of the technique. In general, 57% reported some difficulties coming to the hospital, the time spent out of work being the main problem. Interestingly, 57% were worried during the sessions, mainly due to a fear of faecal urgency. Overall, 88% answered that they were very or somewhat satisfied with the treatment, and almost three-quarters would have agreed to be treated again with it. These results are of special interest in this field but there is lack of data to make external comparisons with other patient populations.

Our study is the first multicentre assessment of patients’ perception of GMA for the treatment of IBD. An important finding was that 60% of patients reported an overall satisfaction with GMA. Moreover, we found that the main factor associated with this satisfaction was the clinical effectiveness of the treatment, while no effect was observed in relation to IBD type, GMA regimen or the number of sessions. These findings are supported by the significant differences with the same trends when patients were asked about their satisfaction with the clinical effectiveness and whether the pros outweighed the cons of GMA. Most importantly, a high proportion of the patients would be willing to receive GMA as a treatment of their IBD if required in the future, regardless of whether the treatment had been effective on this occasion.

As GMA has some specific characteristics, we also considered it relevant to assess its possible drawbacks in clinical practice. We found that the main concern during the sessions was the need to use the toilet, and this result was present independently of the frequency of the sessions prescribed. Furthermore, the time required to receive GMA may be a disadvantage of the therapy in clinical practice. Most of the patients in our cohort (94%) did not consider it an important limitation when asked directly about this factor; however, when they were asked about multiple drawbacks of this technique, the time required in each visit and the uncontrolled gastrointestinal symptoms appeared as the two most common responses. In the subgroup analysis, the use of longer or more frequent sessions was not associated with a different perception. This finding is relevant because the intensive regimen demonstrated a higher effectiveness without increasing the discomfort of the patients related to the time spent in the hospital. Furthermore, as the overall satisfaction with GMA seems to be linked to its clinical effectiveness, our results support the use of the intensive regimen as a reasonable alternative regimen in IBD.

The results found in our population are in line with the previous findings in the Japanese cohort. Taking the two studies together, we can identify patterns in patients’ experience with GMA that seem to be present independently of social and cultural differences. Both cohorts have placed importance on controlling gastrointestinal symptoms during the sessions. Further, the rates of patient’ satisfaction and willingness to be treated again with GMA were comparable. The retrospective design of our study could have led to a recall bias, and also the relatively small number of patients included may have limited our findings. When analysing our results, the influence of these factors should be balanced with the inclusion of patients from multiple centres and the consistent results in line with the previously published literature in this field.

ConclusionsWe have observed that GMA is well accepted and tolerated by patients with IBD in our population and a significant proportion of patients would agree to be treated again with this technique. Importantly, these results are significantly influenced by the effectiveness of this therapy. Regarding future work, there is a need for more high-quality and prospective data including more patients in order to improve GMA treatment and in turn patient satisfaction.

Authors’ contributionsIR-L and JLC designed the study protocol. IR-L, JMB, VG-S, AG, LS, DG, MB-A and JLC managed the patients and compiled the data. IR-L drafted the manuscript. JLC critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestsJosé Luis Cabriada has served as a consultant for Otsuka Pharmaceuticals.