The use of infliximab (IFX) in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has been associated with a 1–6% risk of infusion reactions. The usefulness of premedication with corticosteroids, paracetamol and /or antihistamines is controversial.

AimThe aim of this study is to assess, in IBD patients on IFX, whether there are differences in secondary reactions to the infusion between those who use premedication or not.

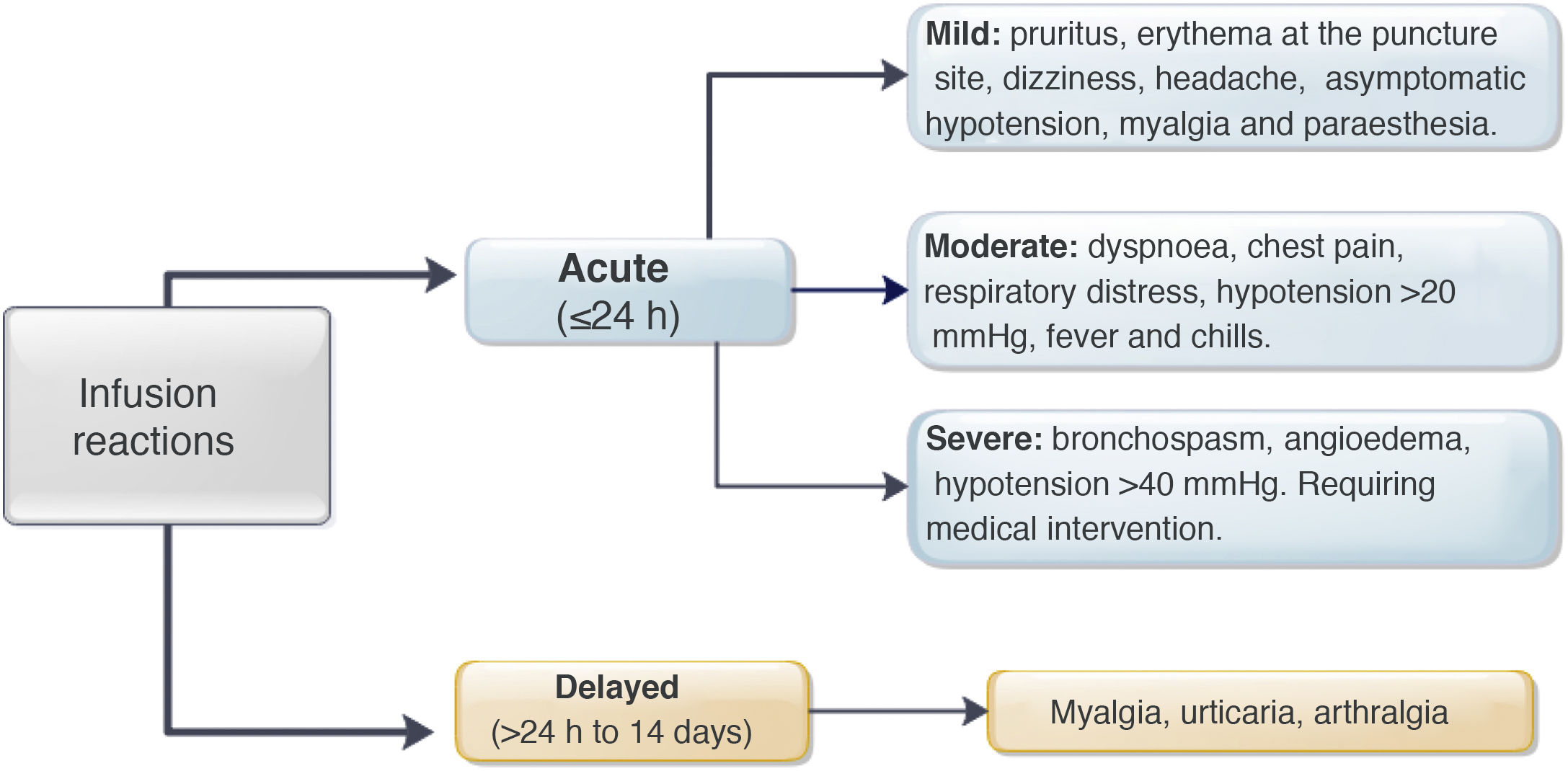

MethodsA retrospective cohort study was performed identifying patients with a diagnosis of IBD who received IFX at our institution between January 2009 and July 2019. Acute reactions were defined as those that occurred in the first 24h post infusion and late reactions for more than 24h. Infusion reactions were classified as mild, moderate and severe. Descriptive and association statistics were used (χ2; p<0.05).

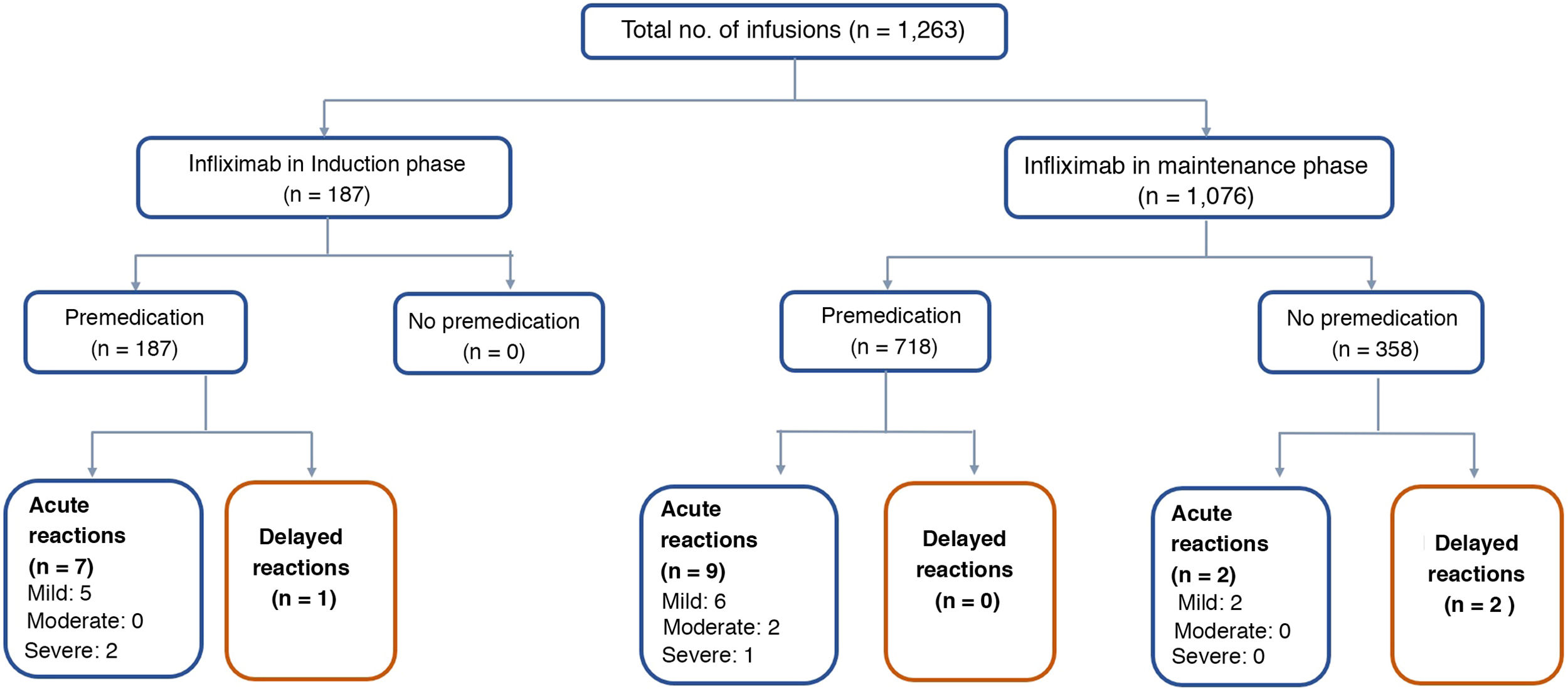

ResultsSixty-four patients were included with 1,263 infusions in total, 52% men. Median infusions per patient was 22 (2–66). All induction infusions were administered with premedication, and in maintenance in 57% of them. Premedication was given with hydrocortisone, chlorphenamine and paracetamol. Most of reactions were acute, mild or moderate in severity and no patient needed to discontinue IFX. In the maintenance group, there were 9/718 (1.2%) infusion reactions with premedication and 4/358 (1.1%) without it (p=0.606). In the induction group, there were 8/187 (4.3%) infusion reactions, significantly higher when compared with both maintenance groups.

ConclusionsIn this group, premedication use during maintenance was not effective at reducing the rate of infusion reactions. These results suggest that premedication would not be necessary.

El uso de infliximab (IFX) en enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII) se ha asociado con un riesgo de 1–6% de reacciones a la infusión. La utilidad de premedicación con corticoides, paracetamol y/o antihistamínicos es controvertido.

ObjetivoEvaluar si en pacientes con EII que utilizan IFX hay diferencias en las reacciones secundarias a infusión entre aquellos que utilizan o no premedicación.

MétodosEstudio descriptivo, observacional, retrospectivo en pacientes con EII, que han utilizado IFX entre enero 2009 y julio 2019. Se definieron como reacciones agudas aquellas ocurridas en las primeras 24hrs.post infusión y tardías después de ese período, clasificándose en leves, moderadas y severas. Se usó estadística descriptiva y de asociación (χ 2; p<0,05).

ResultadosSe incluyeron 1,263 infusiones en un total de 64 pacientes, 52% hombres. Mediana de infusiones por paciente 22 (2–66). El 100% de las infusiones en inducción fueron con premedicación y en mantenimiento el 57%. La premedicación fue realizada con hidrocortisona, clorfenamina y paracetamol. La mayoría de las reacciones fueron agudas, de gravedad leve a moderada y ningún paciente necesitó descontinuar IFX. En mantenimiento hubo 9/718 (1.2%) reacciones a la infusión con premedicación y 4/358 (1.1%) sin ésta, sin diferencias significativas (p=0.606). En inducción hubo 8/187(4.3%) reacciones a la infusión, significativamente mayor al compararlas con ambos grupos de mantenimiento.

ConclusiónEn esta cohorte de pacientes, el no usar premedicación en fase de mantenimiento de IFX no aumentó el número de eventos adversos a este fármaco. Estos resultados sugieren que su indicación no sería necesaria.

The advent of biological therapy signified a major advance in treating patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.1 The first anti-tumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF) available as a therapeutic strategy in IBD was infliximab (IFX), an intravenously administered chimeric IgG1 κ anti-TNF-α antibody.2

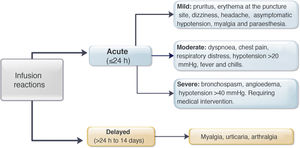

However, administration of this biological drug has been associated with a risk of either acute or delayed infusion reactions.3,4 The acute reactions occur within 24h of administration and affect somewhere in the region of 5–29% of patients and 6% of infusions.3–9 Symptoms can range from mild reactions such as erythema, pruritus, urticaria, fever, chills, myalgia, paraesthesia and asymptomatic hypotension, to severe reactions including anaphylaxis, seizures and symptomatic hypotension.3,9 The mechanisms that lead to these acute reactions are still not fully understood.4,10–13 Type 1 hypersensitivity reactions have been ruled out, as anti-IFX IgE levels are normal in patients who have had acute post-infusion reactions.11 However, premedication continues to be widely used in clinical practice to prevent acute reactions.14–17 This strategy generally includes the use of corticosteroids (prednisone, dexamethasone, hydrocortisone or methylprednisolone), antihistamines (diphenhydramine, loratadine or cetirizine) and antipyretics (paracetamol).7,8,15,18–21 Some have also added antiemetics (ondansetron) and prehydration (normal saline).22,23 In a survey that included 376 adult and paediatric gastroenterologists, 70% reported having prescribed an antihistamine, 64% paracetamol and 48% a corticosteroid before each IFX infusion.16

Delayed reactions appear from 24h to 14 days after the administration of the biological drug and occur in up to 3% of infusions.3,4,9 The most common symptoms are itchy rashes, fever, myalgia and arthralgia.3 The pathogenesis of these reactions is due to a variety of local and systemic inflammatory responses caused by complement fixation and activation which would be triggered by the binding of IFX to anti-IFX antibodies.4 Given the lack of evidence to support the use of premedication or clearly define which group of patients this strategy would benefit, a number of studies have questioned its effectiveness, particularly in patients on maintenance therapy.7,8,22–25

The aim of this study was to assess the effectiveness of premedication in the prevention of acute and delayed adverse reactions after IFX infusion, both in the induction and maintenance phases.

Patients and methodsObservational, descriptive, cross-sectional, analytical study in patients ≥18 years of age with a confirmed diagnosis of Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC) or IBD unclassified, who received IFX from January 2009 to July 2019 in induction and/or maintenance phases, and who were included in the Clínica Las Condes [Las Condes Clinic] Inflammatory Bowel Disease Programme. Patients who were administered the biological drug at another centre were excluded.

Demographic variables (age, gender and smoking) and clinical variables (diagnosis, Montreal classification, years since onset of disease, years since admission to the IBD Programme, current treatment with mesalazine, thiopurines (azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine) and methotrexate, induction or maintenance phase with IFX (dose, duration of infusion and number of weeks since the previous infusion), levels of IFX (measured by ELISA with upper limit >12μg/mL) and anti-IFX antibodies, optimisation requirements (if necessary to increase the dose or shorten the frequency of IFX administration), history of previous IFX use (reason for discontinuation, including loss of response, lack of adherence, withdrawal of biological drug due to clinical remission and mucosal healing), history of surgery for IBD and drug allergies) were obtained from the Clínica Las Condes registry of IBD patients, which is kept for research purposes and was approved by the local Ethics Committee in April 2012.

When starting treatment with IFX, the patients received 5mg/kg at week 0, week 2 and week 6 (induction phase). In the case of severe steroid-refractory UC, at the discretion of the treating gastroenterologist, an optimised scheme was indicated (10mg/kg and/or administration at week 0, week 1 and week 4). During the maintenance phase, the dose was 5mg/kg every eight weeks. Adjustments of doses (10mg/kg) and intervals (every four or six weeks) in this phase were made according to clinical activity and, if available, levels of IFX and anti-IFX antibodies.

Regarding premedication, the type of drug (hydrocortisone, prednisone, paracetamol, chlorphenamine or other type) was recorded, along with its dose and route of delivery. All acute infliximab-related infusion reactions were recorded, including the symptoms, treatment provided,27 and need for emergency medical assessment, hospitalisation and desensitisation. The severity of the reaction was classified according to the definitions identified as mild, moderate or severe (Fig. 1).3,9 In patients with delayed reactions (1–14 days), symptoms and required treatment were recorded.27 Patients at high risk of infusion reaction were defined as those with a history of prior reaction to IFX, delay in infusions (≥10 weeks since the previous infusion) or reintroduction of the biological agent after a period of suspension (≥20 weeks between infusions).24,26–29 Low-risk patients were those who did not meet any of the above criteria.

This study was approved by the institution’s Ethics Committee and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysisIn view of the fact that a reaction could occur with one infusion and not subsequently occur again in the same patient, each infliximab administration was considered as a single event and both risk stratification and frequency of infusion reaction were determined. The results of the study were analysed using the R Commander software program. Categorical variables were analysed through absolute frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were described in terms of measures of central tendency and dispersion depending on data distribution (mean and standard deviation for normal distribution, and median and interquartile range for non-normal distribution). Continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test or Student’s t test, depending on the distribution. Percentage relative frequency was used for categorical variables, and the chi-squared test was used for comparative statistical analysis. A p value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

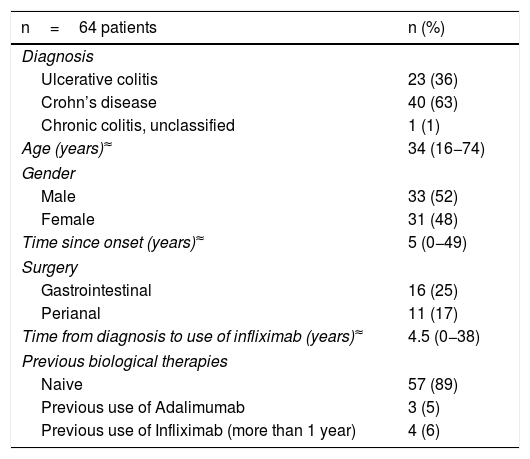

ResultsPatientsThe study included 1,263 IFX infusions in a total of 64 patients. The demographic and clinical data for the patients are shown in Table 1. Forty patients with a diagnosis of CD, 23 with UC and one with IBD unclassified participated in this study; 52% were male, with a median age of 34 (range 16−74), and a median time since disease onset of five years (range 0−49 years). Sixty-two patients had at some point been on combination therapy (IFX plus thiopurines/methotrexate). In relation to IFX, 89% of the patients had not used another biological drug and in four patients it was reintroduced as a strategy more than one year after the last dose (for non-medical reasons). None of the patients had a history of atopy, allergy or anaphylaxis to any drug.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of patients with infliximab.

| n=64 patients | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis | |

| Ulcerative colitis | 23 (36) |

| Crohn’s disease | 40 (63) |

| Chronic colitis, unclassified | 1 (1) |

| Age (years)≈ | 34 (16−74) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 33 (52) |

| Female | 31 (48) |

| Time since onset (years)≈ | 5 (0−49) |

| Surgery | |

| Gastrointestinal | 16 (25) |

| Perianal | 11 (17) |

| Time from diagnosis to use of infliximab (years)≈ | 4.5 (0−38) |

| Previous biological therapies | |

| Naive | 57 (89) |

| Previous use of Adalimumab | 3 (5) |

| Previous use of Infliximab (more than 1 year) | 4 (6) |

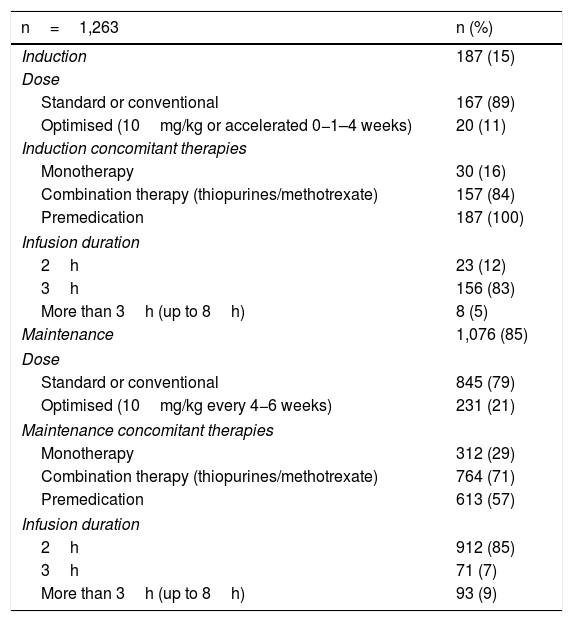

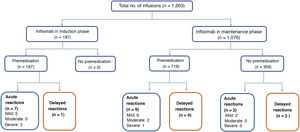

The median number of infusions per patient was 22 (range 2–66). All the patients received the original IFX (Remicade®) and 85% of the infusions were given in the maintenance phase. Both in induction and maintenance, the IFX dose most used was 5mg/kg (89% and 79% respectively) (Table 2). In 74% of cases, the IFX infusions were administered over three hours, in 18% over two hours, and in 8% over more than three hours (up to eight hours). In two patients, IFX desensitisation was performed as per protocol,4,30 with the drug being administered over eight hours in one of them. All (100%) of the infusions in induction and 57% in maintenance were administered after premedication. The premedication consisted of hydrocortisone (100mg in 95% and 200mg 5%), chlorphenamine (10mg) and paracetamol (1g) in all patients. None of the patients received prehydration (normal saline or lactated Ringer's solution) or antiemetics (ondansetron or domperidone) as part of their premedication.

Infliximab infusion characteristics.

| n=1,263 | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Induction | 187 (15) |

| Dose | |

| Standard or conventional | 167 (89) |

| Optimised (10mg/kg or accelerated 0−1–4 weeks) | 20 (11) |

| Induction concomitant therapies | |

| Monotherapy | 30 (16) |

| Combination therapy (thiopurines/methotrexate) | 157 (84) |

| Premedication | 187 (100) |

| Infusion duration | |

| 2h | 23 (12) |

| 3h | 156 (83) |

| More than 3h (up to 8h) | 8 (5) |

| Maintenance | 1,076 (85) |

| Dose | |

| Standard or conventional | 845 (79) |

| Optimised (10mg/kg every 4−6 weeks) | 231 (21) |

| Maintenance concomitant therapies | |

| Monotherapy | 312 (29) |

| Combination therapy (thiopurines/methotrexate) | 764 (71) |

| Premedication | 613 (57) |

| Infusion duration | |

| 2h | 912 (85) |

| 3h | 71 (7) |

| More than 3h (up to 8h) | 93 (9) |

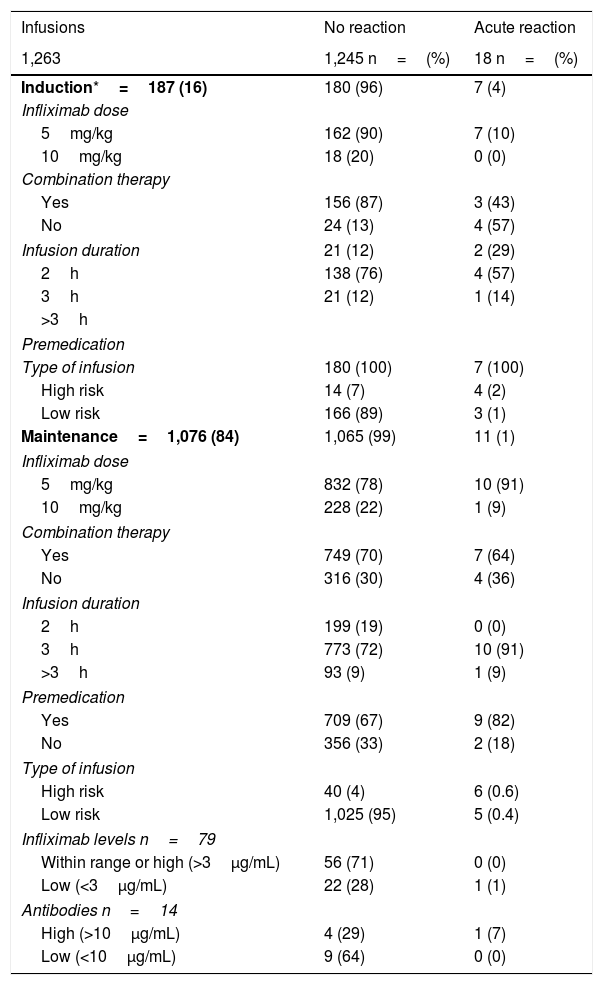

Of the 1,263 infusions analysed in this study, 64 (5%) were defined as high risk: 52 due to a history of an acute reaction after infliximab administration, eight due to a delay in the infusions, and four due to reintroduction of the biological agent more than 10 weeks after the last infusion. In this group, 46 doses were administered during the maintenance phase and in 57% the infliximab dose was 10mg/kg. Premedication was indicated in 85% of the infusions in this group. There were 10 (16%) acute infusion reactions (four in induction and six in maintenance), all with premedication. All the adverse events in the induction phase occurred with the second dose of IFX, with the patients having been premedicated. In maintenance, three events occurred despite the patients having received premedication (Table 3).

Acute post-infusion reactions.

| Infusions | No reaction | Acute reaction |

|---|---|---|

| 1,263 | 1,245 n=(%) | 18 n=(%) |

| Induction*=187 (16) | 180 (96) | 7 (4) |

| Infliximab dose | ||

| 5mg/kg | 162 (90) | 7 (10) |

| 10mg/kg | 18 (20) | 0 (0) |

| Combination therapy | ||

| Yes | 156 (87) | 3 (43) |

| No | 24 (13) | 4 (57) |

| Infusion duration | 21 (12) | 2 (29) |

| 2h | 138 (76) | 4 (57) |

| 3h | 21 (12) | 1 (14) |

| >3h | ||

| Premedication | ||

| Type of infusion | 180 (100) | 7 (100) |

| High risk | 14 (7) | 4 (2) |

| Low risk | 166 (89) | 3 (1) |

| Maintenance=1,076 (84) | 1,065 (99) | 11 (1) |

| Infliximab dose | ||

| 5mg/kg | 832 (78) | 10 (91) |

| 10mg/kg | 228 (22) | 1 (9) |

| Combination therapy | ||

| Yes | 749 (70) | 7 (64) |

| No | 316 (30) | 4 (36) |

| Infusion duration | ||

| 2h | 199 (19) | 0 (0) |

| 3h | 773 (72) | 10 (91) |

| >3h | 93 (9) | 1 (9) |

| Premedication | ||

| Yes | 709 (67) | 9 (82) |

| No | 356 (33) | 2 (18) |

| Type of infusion | ||

| High risk | 40 (4) | 6 (0.6) |

| Low risk | 1,025 (95) | 5 (0.4) |

| Infliximab levels n=79 | ||

| Within range or high (>3μg/mL) | 56 (71) | 0 (0) |

| Low (<3μg/mL) | 22 (28) | 1 (1) |

| Antibodies n=14 | ||

| High (>10μg/mL) | 4 (29) | 1 (7) |

| Low (<10μg/mL) | 9 (64) | 0 (0) |

The remaining 1,199 (95%) infusions were classified as low risk for an acute reaction to IFX; 169 (14%) were induction doses and in 97% the dose was 5mg/kg. Premedication was given in 100% of these cases, with eight acute reactions occurring after IFX administration (three in induction and five in maintenance).

IFX levels were measured in 79 infusions, in a total of 32 patients (Table 3). Nine patients had two measurements and 13 more than three measurements during the study period. The levels ranged from 0.01 to 52.4μg/mL. The presence of anti-IFX antibodies was measured in 14 infusions; two patients had two measurements. Antibody levels were elevated in five infusions (median 45.6μg/mL, range 26.5–125).

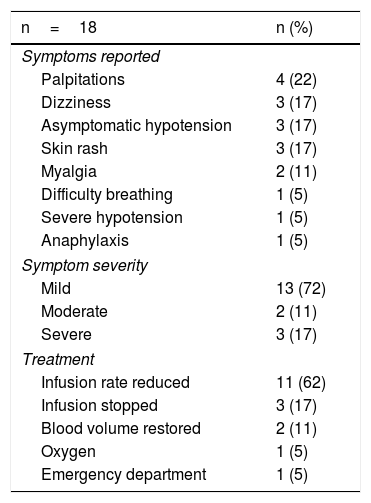

Acute reactionsEighteen acute reactions occurred in this study (1.4% of the infusions), affecting nine patients (14%), with seven of the reactions being in patients with CD. A description of these events, their severity and management is given in Table 4. In terms of severity, 13 were classified as mild, two as moderate and three as severe. The three severe acute reactions were in the group that had received premedication (Fig. 2). In one of these patients, IFX had to be temporarily discontinued, and the desensitisation protocol was applied in two of them, with a good response.4,30 Seven of the acute reactions occurred in the induction phase, six after the second dose. The other 11 reactions occurred during the maintenance phase, nine of them in patients who had received premedication (Fig. 2). The strategies most commonly used to manage acute reactions were decreasing the infusion rate (62%) and stopping the infusion (17%) (Table 4). It was not necessary to discontinue IFX and switch biological drug in any of the patients.

Acute infusion reactions.

| n=18 | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Symptoms reported | |

| Palpitations | 4 (22) |

| Dizziness | 3 (17) |

| Asymptomatic hypotension | 3 (17) |

| Skin rash | 3 (17) |

| Myalgia | 2 (11) |

| Difficulty breathing | 1 (5) |

| Severe hypotension | 1 (5) |

| Anaphylaxis | 1 (5) |

| Symptom severity | |

| Mild | 13 (72) |

| Moderate | 2 (11) |

| Severe | 3 (17) |

| Treatment | |

| Infusion rate reduced | 11 (62) |

| Infusion stopped | 3 (17) |

| Blood volume restored | 2 (11) |

| Oxygen | 1 (5) |

| Emergency department | 1 (5) |

In the univariate analysis, being at high risk was associated with more acute reactions in both induction (p<0.0001) and maintenance (p=0.00007). The use of immunomodulators was associated with a lower rate of adverse reactions, but this was only in the induction phase (p=0.0014) (Table 3).

Delayed reactionsOnly three delayed reactions (0.2% of infusions) were identified in this study. One patient reported myalgia during induction. The other two events occurred in the maintenance phase: one patient who received premedication had arthralgia, and the other, with no premedication, had urticaria. All three patients received chlorphenamine and paracetamol as treatment for these delayed reactions. In only one patient the IFX dose was decreased from 10mg/kg to 5mg/kg every eight weeks. None of the patients had elevated levels of anti-IFX antibodies.

Overall, in the maintenance phase, there were 9/718 (1.2%) reactions to the IFX infusion with and 4/358 (1.1%) without premedication, with no significant differences (p=0.606). In the induction phase there were 8/187 (4.3%) reactions to the infusion, significantly higher compared to both maintenance groups (without premedication p=0.02 and with premedication p=0.008).

DiscussionAdvances have been made in the treatment of IBD over the last 30 years or so with the advent of biological therapy (anti-TNF, anti-integrins and anti-p40 IL-12/23) and, more recently, the use of small molecules. These developments have helped alter the course of the disease and, with that, the quality of life of these patients.31 IFX in particular, in an induction and maintenance regimen, has proven to be highly effective in reducing inflammation, achieving clinical and endoscopic remission, and reducing the number of hospital admissions and the need for surgery.32,33 Early use of IFX has also been shown to change the course of IBD.34

IFX infusion reactions, although uncommon,3–9 are a concern to both the patient and the treating team due to the risk of having to discontinue therapy, especially considering the still limited therapeutic strategies available in the management of IBD. Our results confirm the low rates of acute reactions within the first 24h (1.4% of infusions, 14% of patients) and delayed reactions from 24h to 14 days (0.2% of infusions, 4.7% of patients).

In terms of the severity of the acute reactions, 87% were classified as mild to moderate, very similar to that described by other authors.9,14,23 In the study by Gold et al.,23 which included 7,090 infusions, 83% of the reactions were mild to moderate. However, the rate of mild events was higher in our study (72% vs 57%). The reason for these differences may be the number of patients included, and thus the number of infusions. One recent study of patients who received IFX in an outpatient clinic confirmed that the percentage of serious reactions is low (11.5% of reactions, 0.2% of all infusions).9 The most common post-infusion symptoms in our study were palpitations, dizziness, asymptomatic hypotension and skin rash. Other studies have mentioned additional symptoms such as itching, dyspnoea, myalgia, nausea, urticaria and headache.7,9,23

Of the acute infusion reactions, 39% occurred during the induction phase. Some studies have pointed out that this percentage can reach 100% of events, especially after the second dose.3,14 In our study, six of the seven acute reactions in the induction phase occurred after the second dose.

Sixty-four (5%) of our infusions were defined as high risk and acute reactions occurred following six of those (9%). In a study that included 986 high-risk infusions, only 5.4% had an acute infusion reaction, unrelated to the use of premedication, regardless of the type of drug used as strategy.23 In our study, however, there was a higher rate of acute infusion reactions both during induction and maintenance in the high-risk group. Prospective studies with a larger number of patients would help define the effectiveness of premedication in this scenario. In the low-risk group, premedication has been shown to have no protective effect, with adverse infusion reactions only occurring in 1% of cases.23 Our results confirm this trend; only 1% of the infusions in this group caused an acute reaction.

Combination therapy with IFX and thiopurines/methotrexate has been suggested as a strategy for decreasing the likelihood of post-infusion reactions.4,35 In our study, the combined use of immunomodulators in the induction phase was associated with fewer adverse events. Other studies have shown that patients who develop anti-IFX antibodies have twice the risk of developing an acute reaction and up to six times the risk of a serious IFX infusion event.13,37 One randomised controlled study showed that, although premedication with hydrocortisone decreased the formation of antibodies against IFX, it did not eliminate the risk of developing an infusion reaction.22 However, other studies have not managed to confirm this effect in patients receiving IFX treatment in a maintenance regimen.36 In our study, only one of the patients who had antibodies had an infusion reaction. It is important to point out that the technique used to measure the presence of antibodies only allowed them to be measured when IFX levels were low or absent.38

Although there are no specific guidelines for the management of acute post-IFX reactions, according to treatment recommendations based on case studies3,8,9,23 and expert opinion,4,39 decreasing the infusion rate, temporary discontinuation of IFX, use of normal saline or lactated Ringer’s solution and the use of drugs are the measures most often suggested, similar to those that were applied in our patients. Unlike other studies,9,14,39 definitive suspension of biological therapy was not required in any of our patients.

Delayed reactions after IFX administration only occurred on three occasions (0.2% of infusions), confirming the low frequency shown in other studies.3,4,9 In the Cheifetz et al. study3 only 0.6% of patients had a delayed reaction within 14 days after administration of infliximab. As described by other authors,3,4,9 the most common symptoms were urticaria, arthralgia and myalgia. The suggested treatment for these reactions is paracetamol and antihistamine,3,4,9 and this is what was used in our patients.

Although premedication with corticosteroids, antihistamines and antipyretics is frequently used to prevent the development of an IFX infusion reaction, adequate validation of the use of these treatments is lacking.16 Our study confirms that premedication with corticosteroids, paracetamol and chlorphenamine during the maintenance phase does not reduce the risk of developing an acute infusion reaction (nine of the 11 events were in the group premedicated prior to IFX administration). Studies have shown that premedication, either with hydrocortisone22 or the combination of intravenous steroids, antihistamines and paracetamol, does not prevent the development of acute IFX infusion reactions.7,9 When classifying the groups according to risk, our results also failed to show that premedication reduced the risk of an acute infusion reaction in the high-risk group, confirming the findings reported by others.23 Moreover, also in line with other authors,40 premedication did not reduce the risk of developing a severe acute reaction. The three severe acute reactions occurred in patients who had received premedication. We did not assess the use of normal saline as premedication, but Gold et al.23 showed that the use of prehydration, alone or in combination with other drugs, could reduce the risk of an acute IFX infusion reaction in high-risk patients. However, validation of these results is obviously required before such an indication can be suggested.

It is important to bear in mind that, like any drug, corticosteroids and antihistamines can also cause undesirable effects. Those associated with corticosteroids include drowsiness, blurred vision, abdominal pain and decreased alertness.41 Moreover, the use of corticosteroids as premedication is not optimal considering that patients with IBD have more exposure to these drugs as a treatment strategy for their underlying disease, along with the accompanying complications.31 Antihistamines can be associated with drowsiness and decreased alertness, which can prolong the patient’s stay at the infusion clinic or make it necessary for the patient to be accompanied.42 Interestingly, in a prospective study that included 1,632 patients with rheumatological conditions and IBD, the use of diphenhydramine was associated with an increased incidence of infusion reactions (OR 1.58; p=0.0007).7

Prospective studies have confirmed the effectiveness of biosimilar drugs in inducing and maintaining remission in patients with CD and UC.39 Although the biosimilar Remsima® is available in Chile, no patients received it during the time of this study. There is evidence that biosimilars would have a low immunogenicity and a similar rate of acute infusion reactions to the original drug, being higher in patients with previous exposure to an anti-TNF who developed antibodies during the induction phase.43

Our study has certain strengths. As it is a cross-sectional study and shows the experience of a tertiary hospital with an established IBD programme, it provides insight into routine clinical practice. Unlike other studies,9,16,23 the premedication was standardised in all the patients; the use of corticosteroids, paracetamol and chlorphenamine in this group means that real conclusions can be drawn about the effectiveness of this strategy in preventing the development of infusion reactions. Nevertheless, we know there are also limitations. The number of patients included in this study is low compared to other studies. However, from the number of infusions in the maintenance phase, with or without premedication, we are able to conclude that, in patients without risk factors for developing adverse events, the use of premedication may not be effective in preventing acute or delayed IFX infusion reactions. Secondly, as all patients in the induction phase were premedicated, we cannot confirm its effectiveness in this scenario and advise whether or not to use this strategy. Thirdly, we were not able to accurately define the time between the administration of the premedication, the start of the IFX infusion and the timing of the infusion reaction. The pharmacokinetics of the drugs used in premedication have to be considered when defining their role in the development of infusion reactions, especially when acute. In the Gold et al. study, the majority of acute reactions occurred within 15min of starting the infusion (data not shown).23 Last of all, in this study it was not possible to assess the presence of levels and antibodies in all the patients who developed acute or delayed IFX infusion reactions.

In conclusion, our study suggests that acute and delayed IFX infusion reactions are rare, mostly mild to moderate, and can be managed successfully without suspending the biological therapy. Although during the maintenance phase there may be scenarios where premedication should be considered, we suggest not using it routinely. Prospective studies have yet to define the role of this strategy in the induction phase.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Nuñez F. P, Quera R, Simian D, Flores L, Figueroa C, Ibañez P, et al., Infliximab en enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. ¿Es necesario premedicar? Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:321–329.