The effectiveness of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment seems to be lower in people who inject drugs (PWID). We analyze the influence of various factors as psychiatric disorders and opioid substitution therapy (OST) on the treatment with direct-acting antivirals (DAA) in this collective.

Patients and methodsThree hundred thirty-two PWID patients were treated with DAA in 12 Spanish hospitals between 2004 and 2020. They were catalogued in recent and former consumers (if the last consumption was in the last 3 years) and several variables were included, evaluating the effectiveness of the treatment according to the viral load 12 weeks after the end of the treatment with the parameter “sustained viral response” (SVR12).

Results23.4% were recent consumers and 27,7% were on OST. 41.5% had any diagnosis of psychiatric disorder. SVR12 was 84.04%, ascending to 96.21% when excluded from the analyses the patients lost to follow-up (12,7%). SVR12 was lower due to an increase in the loss to follow-up in recent consumers and other factors like OST, being in prison the last 5 years, naïve patients, generalized anxiety disorder and benzodiazepine consumption.

ConclusionsThe effectiveness of the HCV treatment with DAA in PWID is similar than in general population in patients whit an appropriate follow-up. It is important to maintain a closer follow-up in patients on OST, recent consumers and those with psychiatric disorders.

La efectividad del tratamiento del virus de la hepatitis C (VHC) parece ser menor en usuarios de drogas por vía parenteral (UDVP). Analizamos la influencia de diversos factores como los trastornos psiquiátricos y la terapia de sustitución con opiáceos (TSO) en el tratamiento con antivirales de acción directa (AAD) de este colectivo.

Pacientes y métodosTrescientos treinta y dos pacientes UDVP fueron tratados con AAD en 12 hospitales de España entre 2004 y 2020. Se catalogaron, si se disponía del dato, en consumidores recientes y pasados (según si el último consumo fue en los últimos 3 años) y se recogieron diversas variables, evaluándose la efectividad del tratamiento según la carga viral 12 semanas tras la finalización del tratamiento con el parámetro «respuesta viral sostenida» (RVS12).

ResultadosEl 23,4% eran consumidores recientes y el 27,7% estaban en TSO. El 41,5% presentaban algún diagnóstico de enfermedad psiquiátrica. La RVS12 fue del 84,04%, ascendiendo a 96,21% al excluir del análisis a los pacientes que perdieron el seguimiento (12,7%). La RVS12 fue significativamente inferior debido a un aumento de la pérdida de seguimiento en consumidores recientes, aquellos en TSO, los que habían estado en prisión los últimos 5 años y pacientes naive, así como en el trastorno de ansiedad generalizada y consumidores de benzodiacepinas.

ConclusionesLa efectividad del tratamiento del VHC con AAD en UDVP es similar a la población general si se consigue un adecuado seguimiento. Es importante realizar un seguimiento más estrecho en pacientes en TSO, consumidores recientes y aquellos con patología psiquiátrica.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection currently stands among the leading causes of chronic liver disease, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.1

Traditional treatment for the disease was not very effective, with high rates of side effects;2 since 2013, with the advent of new oral direct-acting antivirals, the treatment regimens for the disease have achieved high effectiveness, low rates of side effects and interactions, and ease of dosage.1,3,4 They have been so successful that the World Health Organization (WHO) has set a goal of global eradication of HCV by 2030.5

To achieve this goal, special attention must be paid to some difficult-to-treat groups such as people who inject drugs (PWID).6

As HCV is essentially transmitted via the parenteral route, PWID currently constitute the group with the highest prevalence of HCV infection (60%) and account for the largest share of incidental cases (80%),7 especially in developed countries.1,8

PWID not only are the main transmitters of the virus given its aetiopathogenesis, but also often have both medical and psychiatric comorbidities;9 these factors increase the speed of progression of liver disease10 and complicate decision-making with regard to its management.11,12

PWID have traditionally been seen to be excluded from treatment due to lower effectiveness, poor adherence with loss to follow-up,2,13 more side effects and a high risk of reinfection.6 For these reasons, at present, a significant percentage of these individuals remain untreated in Spain.14 However, various studies have shown lower treatment effectiveness to be influenced more by problems with adherence to treatment than by the effectiveness of the drugs themselves.15,16

The objective of this study was to assess the effectiveness of treatment with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) in the subgroup of patients who are PWID with HCV, as well as how variables such as mental illnesses and opioid substitution therapy (OST) influence said effectiveness.

Materials and methodsParticipantsA multi-centre collaborative cohort study was conducted with a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data on patients treated for HCV between July 2014 and December 2020 at 12 hospitals in Spain. The study included patients over 18 years of age diagnosed with chronic HCV and treated with DAAs, whether or not they had cirrhosis and whether they were treatment-naïve or previously treated. The treatment regimen was that indicated by each physician responsible according to the clinical guidelines that were current at that time. Treatment duration was eight, 12, 16 or 24 weeks, with ribavirin (RVB) added or not added at the discretion of the corresponding physicians.

VariablesThe following variables were collected: age, sex, presence of diabetes mellitus, degree of liver fibrosis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, imprisonment in the past five years, viral genotype, cirrhosis, decompensation, viral load and having or not having received prior treatment. Regarding toxic habits, patients were classified as recent drug users if their date of last use was in the past three years, or past drug users if their date of last use was earlier than that (this classification being consistent with prior studies). They were also classified with respect to alcohol use (analysed according to whether they consumed more than 30 g or more than 80 g of alcohol per day) and additional use of marijuana and cocaine at present. Whether or not patients were on OST and, if so, their specific treatment type were recorded.

Any psychiatric diagnoses unrelated to drugs according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V), and the types of drugs used to treat them were included as well.

Degree of liver fibrosis was evaluated by means of liver biopsy, fibrosis scores, transient elastography (FibroScan®), MELD scores and Child-Pugh scores. The cut-off values for elastography were the following: F0-1 up to 6.9 kPa; F2 7–9.4 kPa; F3 9.5–12.4 kPa.; F4 as of 12.5 kPa.

Follow-up was conducted in an initial visit, an end-of-treatment visit and a 12 weeks post-treatment visit. HCV cure was defined as an undetectable HCV viral load 12 weeks after the conclusion of the infection (sustained virologic response after 12 weeks [SVR12]); viral load was also determined at the end of treatment. Viral load was measured using a COBAS® TaqMan® HCV assay (version 2.0; Roche), with a lower limit of quantitation of 15 IU/mL and a lower limit of detection of 10 IU/mL.

Theory/calculationsStatistical analysis was performed with the software programme SPSS®, version 23. Baseline characteristics were analysed using measures of frequency (absolute numbers and percentages) for qualitative variables, and mean (with 95% CI) and standard deviation for quantitative variables. The SVR12 obtained between the different subgroups was calculated based on recent or past use and being or not being on OST, and a univariate analysis based on demographic characteristics was performed.

To compare categorical variables, the chi-squared statistical test or Fisher's exact test was used, as applicable. To compare quantitative variables, analysis of variance (ANOVA), the Kruskal–Wallis test, the Mann–Whitney U test or Student's t-test was used, as applicable. In all cases, differences with a comparison test-associated p value less than or equal to 0.05 were considered significant.

ResultsDemographic characteristicsOf a total of 332 PWID, data corresponding to date of last use were available in 188; of them, 76.6% were past users (more than three years since their last use) and 23.4% were recent users (less than three years since their last use).

Out of 188 patients, 52 (27.7%) were on OST. Among these, 57.7% were recent users and 42.3% were past users.

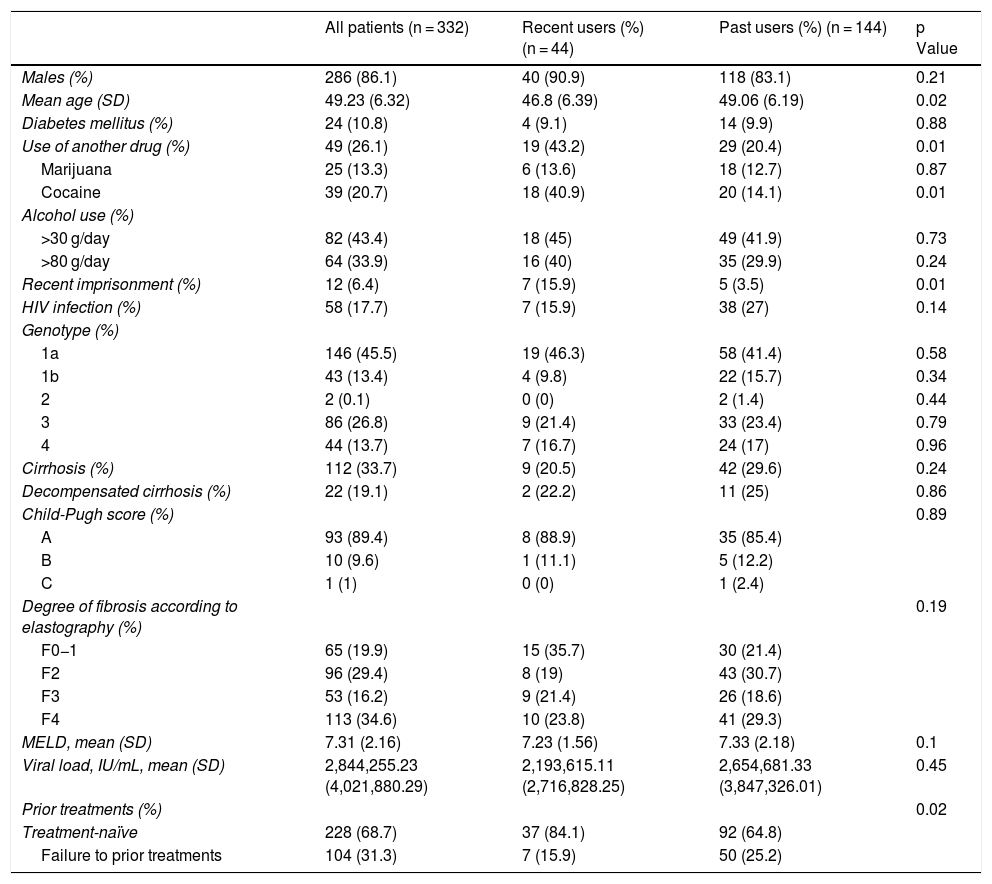

The following variables were collected: age, sex, cause of infection, presence of diabetes mellitus, HIV infection, genotype, cirrhosis, decompensation, Child-Pugh score, baseline FibroScan®, MELD value, viral load, prior treatment and use of alcohol and other drugs. These variables were segmented by whether patients were recent or past users, specifying the p value for the differences between the two groups (Table 1).

Demographic characteristics of the patients.

| All patients (n = 332) | Recent users (%) (n = 44) | Past users (%) (n = 144) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males (%) | 286 (86.1) | 40 (90.9) | 118 (83.1) | 0.21 |

| Mean age (SD) | 49.23 (6.32) | 46.8 (6.39) | 49.06 (6.19) | 0.02 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 24 (10.8) | 4 (9.1) | 14 (9.9) | 0.88 |

| Use of another drug (%) | 49 (26.1) | 19 (43.2) | 29 (20.4) | 0.01 |

| Marijuana | 25 (13.3) | 6 (13.6) | 18 (12.7) | 0.87 |

| Cocaine | 39 (20.7) | 18 (40.9) | 20 (14.1) | 0.01 |

| Alcohol use (%) | ||||

| >30 g/day | 82 (43.4) | 18 (45) | 49 (41.9) | 0.73 |

| >80 g/day | 64 (33.9) | 16 (40) | 35 (29.9) | 0.24 |

| Recent imprisonment (%) | 12 (6.4) | 7 (15.9) | 5 (3.5) | 0.01 |

| HIV infection (%) | 58 (17.7) | 7 (15.9) | 38 (27) | 0.14 |

| Genotype (%) | ||||

| 1a | 146 (45.5) | 19 (46.3) | 58 (41.4) | 0.58 |

| 1b | 43 (13.4) | 4 (9.8) | 22 (15.7) | 0.34 |

| 2 | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.4) | 0.44 |

| 3 | 86 (26.8) | 9 (21.4) | 33 (23.4) | 0.79 |

| 4 | 44 (13.7) | 7 (16.7) | 24 (17) | 0.96 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 112 (33.7) | 9 (20.5) | 42 (29.6) | 0.24 |

| Decompensated cirrhosis (%) | 22 (19.1) | 2 (22.2) | 11 (25) | 0.86 |

| Child-Pugh score (%) | 0.89 | |||

| A | 93 (89.4) | 8 (88.9) | 35 (85.4) | |

| B | 10 (9.6) | 1 (11.1) | 5 (12.2) | |

| C | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.4) | |

| Degree of fibrosis according to elastography (%) | 0.19 | |||

| F0−1 | 65 (19.9) | 15 (35.7) | 30 (21.4) | |

| F2 | 96 (29.4) | 8 (19) | 43 (30.7) | |

| F3 | 53 (16.2) | 9 (21.4) | 26 (18.6) | |

| F4 | 113 (34.6) | 10 (23.8) | 41 (29.3) | |

| MELD, mean (SD) | 7.31 (2.16) | 7.23 (1.56) | 7.33 (2.18) | 0.1 |

| Viral load, IU/mL, mean (SD) | 2,844,255.23 (4,021,880.29) | 2,193,615.11 (2,716,828.25) | 2,654,681.33 (3,847,326.01) | 0.45 |

| Prior treatments (%) | 0.02 | |||

| Treatment-naïve | 228 (68.7) | 37 (84.1) | 92 (64.8) | |

| Failure to prior treatments | 104 (31.3) | 7 (15.9) | 50 (25.2) | |

Recent drug users were significantly younger and had significantly higher rates of cocaine use, recent imprisonment and lack of previous treatment.

Data on psychiatric history were available in 188 patients. Seventy-eight patients (41.5%) had at least one diagnosed mental illness; the sum of these patients and patients on OST diagnosed with "substance abuse disorder" (SAD) was 110 (58.5%).

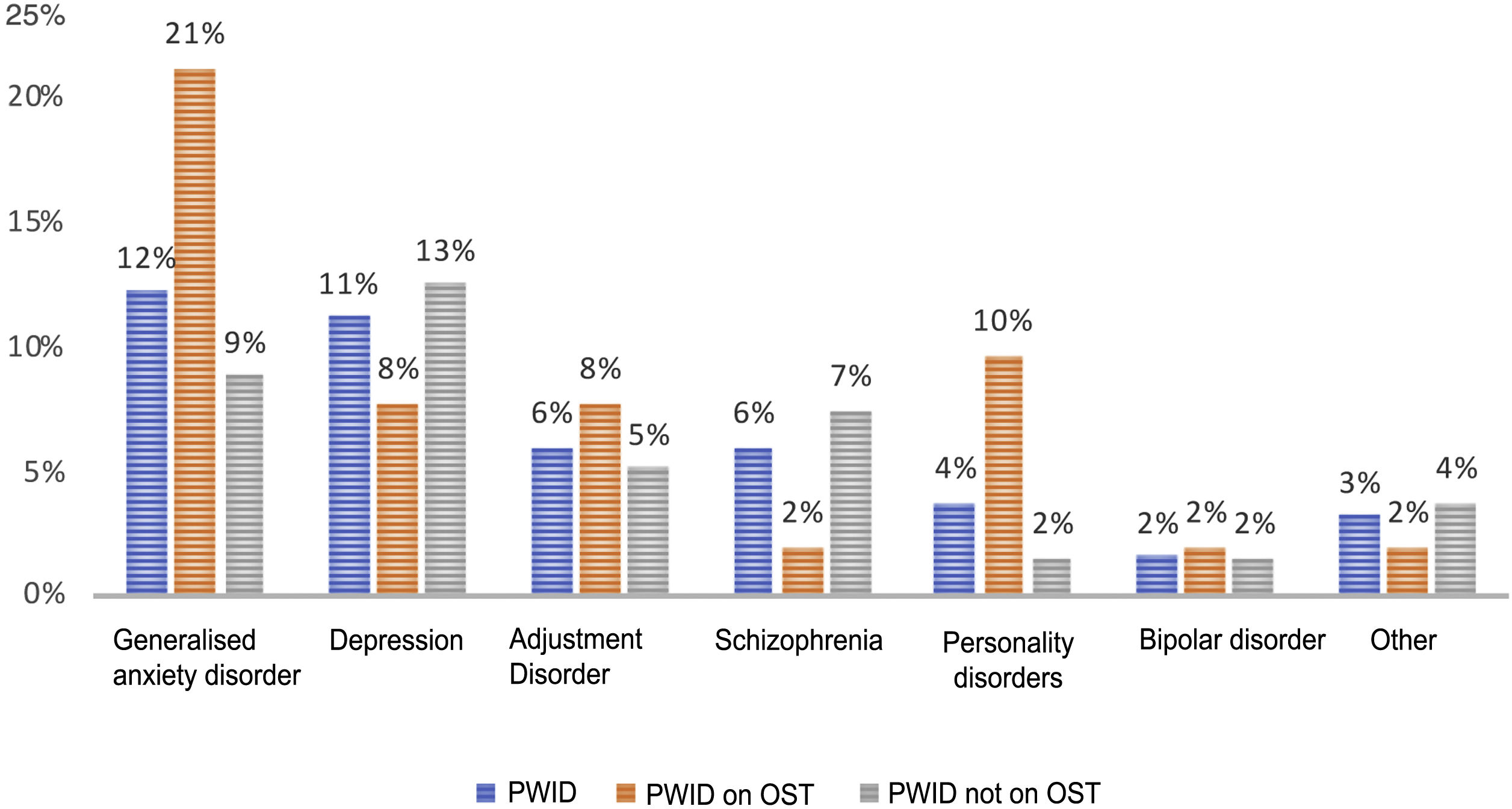

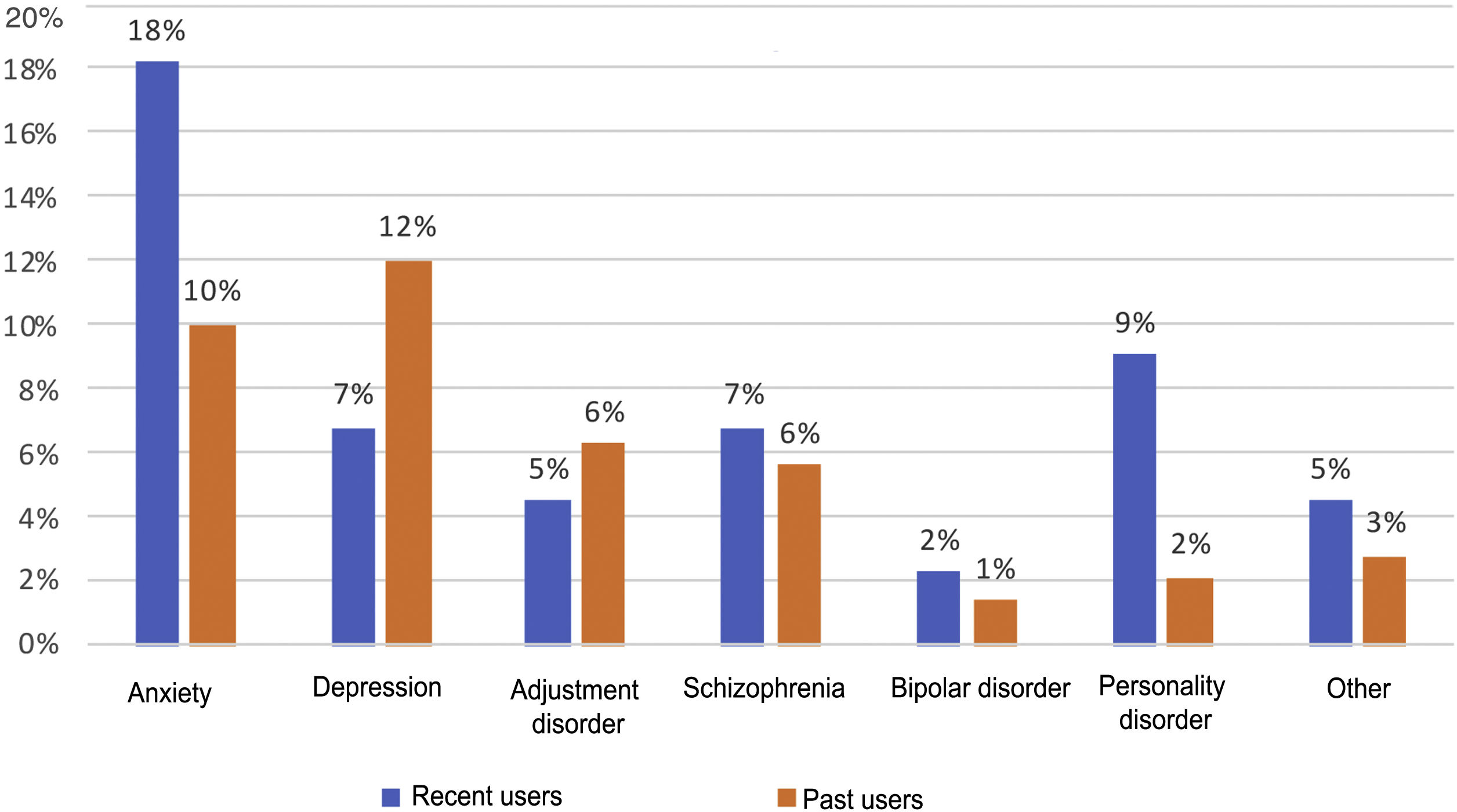

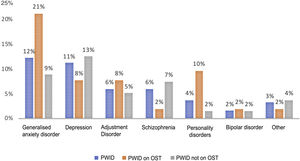

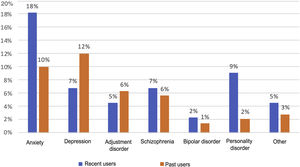

Psychiatric disorders (excluding SAD) were analysed in the general sample of PWID, by OST or no OST and by date of last use (Figs. 1 and 2). In order of frequency, the most prevalent psychiatric disorder in the general PWID population was generalised anxiety disorder (n = 23), followed by major depression (n = 21); adjustment disorders (n = 11: seven mixed, one with depressed mood and three with anxiety); schizophrenia (n = 11); personality disorders (n = 7: one antisocial, one borderline, one dissocial, one cluster C, one not otherwise specified with an impulse-control component, one not otherwise specified and one with dysfunctional traits); bipolar disorder (n = 3); and other (n = 6), including frequent attempts at self-harm with no established diagnosis (n = 2), panic disorder/agoraphobia, Diogenes syndrome, insomnia disorder and psychotic disorder not otherwise specified.

Patients on OST showed higher rates of generalised anxiety disorder (p = 0.02) and personality disorders (p = 0.01) compared to other patients; they did not show higher rates of other psychiatric disorders.

Recent users, like patients on OST, showed higher rates of personality disorders (p = 0.03) and no differences in terms of rates of other disorders.

The median number of psychiatric medications taken was two, the minimum was zero and the maximum was 11. The drugs most commonly used by patients diagnosed with psychiatric disorders, in order of frequency, were benzodiazepines (38.3%), followed by quetiapine and similar drugs (14.4%), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (12.2%), mirtazapine (9.6%), risperidone (5.9%), desvenlafaxine (3.2%), gabapentin (3.2%), pregabalin (2.7%), trazodone (2.1%), clomethiazole (1.6%), tiapride (1.1%), and amitriptyline (1.1%).

Drug use in patients on OST was significantly higher than in other psychiatric patients, with a median of three drugs as well as significantly higher use of benzodiazepines and quetiapine. Of patients on OST, 36 were on treatment with methadone (69.2%), 13 were on treatment with buprenorphine/naloxone (25%) and the remaining three (5.8%) were on unspecified treatment.

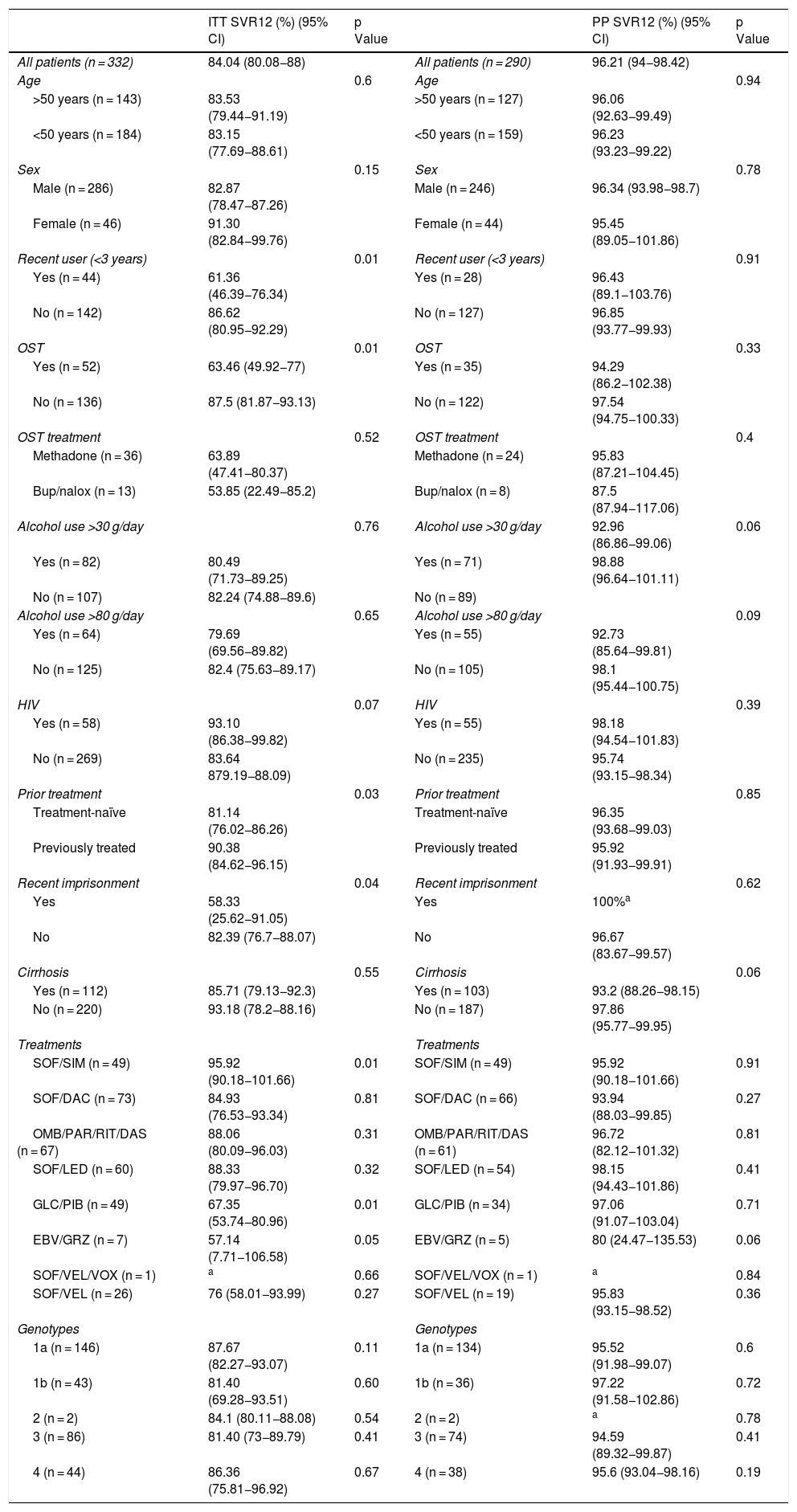

SVR12 resultsOf the patients who started treatment, one died of colon cancer (0.3%). Viral load 12 weeks after finishing treatment was not documented in a total of 42 patients (12.7%): the patient who died, the patients who did not attend their 12 weeks post-treatment visit and the patients who suspended treatment. Overall SVR12 results were 84.04%, with this percentage rising to 96.21% when negative results for patients lost to follow-up were excluded.

SVR12 levels were analysed by sex, age, date of last use, OST, type of OST, alcohol use, treatment regimen, genotype, presence of cirrhosis and HIV — both by intention-to-treat analysis (counting patients for whom no data were available as negative) and per-protocol analysis (excluding negative results for patients lost to follow-up) — yielding a p value for comparison of dichotomous categories (Table 2).

Overall SVR12 results according to per-protocol and intention-to-treat analysis.

| ITT SVR12 (%) (95% CI) | p Value | PP SVR12 (%) (95% CI) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (n = 332) | 84.04 (80.08−88) | All patients (n = 290) | 96.21 (94−98.42) | ||

| Age | 0.6 | Age | 0.94 | ||

| >50 years (n = 143) | 83.53 (79.44−91.19) | >50 years (n = 127) | 96.06 (92.63−99.49) | ||

| <50 years (n = 184) | 83.15 (77.69−88.61) | <50 years (n = 159) | 96.23 (93.23−99.22) | ||

| Sex | 0.15 | Sex | 0.78 | ||

| Male (n = 286) | 82.87 (78.47−87.26) | Male (n = 246) | 96.34 (93.98−98.7) | ||

| Female (n = 46) | 91.30 (82.84−99.76) | Female (n = 44) | 95.45 (89.05−101.86) | ||

| Recent user (<3 years) | 0.01 | Recent user (<3 years) | 0.91 | ||

| Yes (n = 44) | 61.36 (46.39−76.34) | Yes (n = 28) | 96.43 (89.1−103.76) | ||

| No (n = 142) | 86.62 (80.95−92.29) | No (n = 127) | 96.85 (93.77−99.93) | ||

| OST | 0.01 | OST | 0.33 | ||

| Yes (n = 52) | 63.46 (49.92−77) | Yes (n = 35) | 94.29 (86.2−102.38) | ||

| No (n = 136) | 87.5 (81.87−93.13) | No (n = 122) | 97.54 (94.75−100.33) | ||

| OST treatment | 0.52 | OST treatment | 0.4 | ||

| Methadone (n = 36) | 63.89 (47.41−80.37) | Methadone (n = 24) | 95.83 (87.21−104.45) | ||

| Bup/nalox (n = 13) | 53.85 (22.49−85.2) | Bup/nalox (n = 8) | 87.5 (87.94−117.06) | ||

| Alcohol use >30 g/day | 0.76 | Alcohol use >30 g/day | 92.96 (86.86−99.06) | 0.06 | |

| Yes (n = 82) | 80.49 (71.73−89.25) | Yes (n = 71) | 98.88 (96.64−101.11) | ||

| No (n = 107) | 82.24 (74.88−89.6) | No (n = 89) | |||

| Alcohol use >80 g/day | 0.65 | Alcohol use >80 g/day | 0.09 | ||

| Yes (n = 64) | 79.69 (69.56−89.82) | Yes (n = 55) | 92.73 (85.64−99.81) | ||

| No (n = 125) | 82.4 (75.63−89.17) | No (n = 105) | 98.1 (95.44−100.75) | ||

| HIV | 0.07 | HIV | 0.39 | ||

| Yes (n = 58) | 93.10 (86.38−99.82) | Yes (n = 55) | 98.18 (94.54−101.83) | ||

| No (n = 269) | 83.64 879.19−88.09) | No (n = 235) | 95.74 (93.15−98.34) | ||

| Prior treatment | 0.03 | Prior treatment | 0.85 | ||

| Treatment-naïve | 81.14 (76.02−86.26) | Treatment-naïve | 96.35 (93.68−99.03) | ||

| Previously treated | 90.38 (84.62−96.15) | Previously treated | 95.92 (91.93−99.91) | ||

| Recent imprisonment | 0.04 | Recent imprisonment | 0.62 | ||

| Yes | 58.33 (25.62−91.05) | Yes | 100%a | ||

| No | 82.39 (76.7−88.07) | No | 96.67 (83.67−99.57) | ||

| Cirrhosis | 0.55 | Cirrhosis | 0.06 | ||

| Yes (n = 112) | 85.71 (79.13−92.3) | Yes (n = 103) | 93.2 (88.26−98.15) | ||

| No (n = 220) | 93.18 (78.2−88.16) | No (n = 187) | 97.86 (95.77−99.95) | ||

| Treatments | Treatments | ||||

| SOF/SIM (n = 49) | 95.92 (90.18−101.66) | 0.01 | SOF/SIM (n = 49) | 95.92 (90.18−101.66) | 0.91 |

| SOF/DAC (n = 73) | 84.93 (76.53−93.34) | 0.81 | SOF/DAC (n = 66) | 93.94 (88.03−99.85) | 0.27 |

| OMB/PAR/RIT/DAS (n = 67) | 88.06 (80.09−96.03) | 0.31 | OMB/PAR/RIT/DAS (n = 61) | 96.72 (82.12−101.32) | 0.81 |

| SOF/LED (n = 60) | 88.33 (79.97−96.70) | 0.32 | SOF/LED (n = 54) | 98.15 (94.43−101.86) | 0.41 |

| GLC/PIB (n = 49) | 67.35 (53.74−80.96) | 0.01 | GLC/PIB (n = 34) | 97.06 (91.07−103.04) | 0.71 |

| EBV/GRZ (n = 7) | 57.14 (7.71−106.58) | 0.05 | EBV/GRZ (n = 5) | 80 (24.47−135.53) | 0.06 |

| SOF/VEL/VOX (n = 1) | a | 0.66 | SOF/VEL/VOX (n = 1) | a | 0.84 |

| SOF/VEL (n = 26) | 76 (58.01−93.99) | 0.27 | SOF/VEL (n = 19) | 95.83 (93.15−98.52) | 0.36 |

| Genotypes | Genotypes | ||||

| 1a (n = 146) | 87.67 (82.27−93.07) | 0.11 | 1a (n = 134) | 95.52 (91.98−99.07) | 0.6 |

| 1b (n = 43) | 81.40 (69.28−93.51) | 0.60 | 1b (n = 36) | 97.22 (91.58−102.86) | 0.72 |

| 2 (n = 2) | 84.1 (80.11−88.08) | 0.54 | 2 (n = 2) | a | 0.78 |

| 3 (n = 86) | 81.40 (73−89.79) | 0.41 | 3 (n = 74) | 94.59 (89.32−99.87) | 0.41 |

| 4 (n = 44) | 86.36 (75.81−96.92) | 0.67 | 4 (n = 38) | 95.6 (93.04−98.16) | 0.19 |

Bup/nalox: buprenorphine/naloxone; CI: confidence interval; DAC: daclatasvir; DAS: dasabuvir; EBV: elbasvir; GLC: glecaprevir; GRZ: grazoprevir; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; ITT: intention-to-treat; LED: ledipasvir; OMB: ombitasvir; PAR: paritaprevir; PIB: pibrentasvir; PP: per-protocol; RBV: ribavirin; RIT: ritonavir; SIM: simeprevir; SOF: sofosbuvir; VEL: velpatasvir; VOX: voxilaprevir.

The use of other drugs at the time of treatment (marijuana and/or cocaine) was not associated with a lower response.

SVR12 rates were significantly higher for all variables when patients lost to follow-up were excluded from analysis.

Intention-to-treat analysis revealed a lower SVR12 rate in recent users (<3 years), those who were on OST, those who had been imprisoned in the past five years, patients not previously treated (treatment-naïve patients) and patients on certain treatment regimens (sofosbuvir plus simeprevir and glecaprevir/pibrentasvir); SVR12 was similar across all other study variables. However, per-protocol analysis found no significant differences in outcomes compared to other patients.

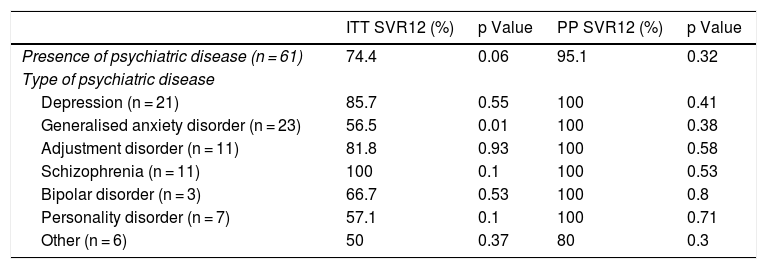

Similarly, the relationship between different psychiatric disorders and SVR12 results was studied by both intention-to-treat and per-protocol analysis (Table 3).

SVR12 and psychiatric disorders.

| ITT SVR12 (%) | p Value | PP SVR12 (%) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of psychiatric disease (n = 61) | 74.4 | 0.06 | 95.1 | 0.32 |

| Type of psychiatric disease | ||||

| Depression (n = 21) | 85.7 | 0.55 | 100 | 0.41 |

| Generalised anxiety disorder (n = 23) | 56.5 | 0.01 | 100 | 0.38 |

| Adjustment disorder (n = 11) | 81.8 | 0.93 | 100 | 0.58 |

| Schizophrenia (n = 11) | 100 | 0.1 | 100 | 0.53 |

| Bipolar disorder (n = 3) | 66.7 | 0.53 | 100 | 0.8 |

| Personality disorder (n = 7) | 57.1 | 0.1 | 100 | 0.71 |

| Other (n = 6) | 50 | 0.37 | 80 | 0.3 |

Having psychiatric disease was not associated with significantly lower HCV cure rates. No relationship was found between number of psychiatric drugs and SVR12 (p = 0.39).

No particular drugs were associated with a lower infection cure rate, apart from benzodiazepines (69.4% versus 87.6%; p = 0.02).

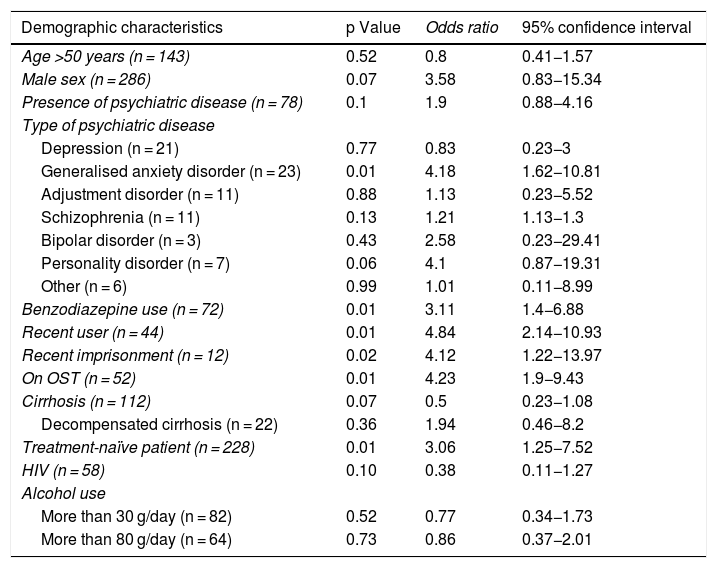

Analysis of patients lost to follow-upAs response rates were significantly higher in the per-protocol analysis, the characteristics of the patients lost to follow-up 12 weeks into the post-treatment period were analysed. Simple logistic regression was performed between each baseline characteristic and loss to follow-up within the sample; the results appear in Table 4.

Relationship between demographic characteristics and loss to follow-up 12 weeks into the post-treatment period.

| Demographic characteristics | p Value | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age >50 years (n = 143) | 0.52 | 0.8 | 0.41−1.57 |

| Male sex (n = 286) | 0.07 | 3.58 | 0.83−15.34 |

| Presence of psychiatric disease (n = 78) | 0.1 | 1.9 | 0.88−4.16 |

| Type of psychiatric disease | |||

| Depression (n = 21) | 0.77 | 0.83 | 0.23−3 |

| Generalised anxiety disorder (n = 23) | 0.01 | 4.18 | 1.62−10.81 |

| Adjustment disorder (n = 11) | 0.88 | 1.13 | 0.23−5.52 |

| Schizophrenia (n = 11) | 0.13 | 1.21 | 1.13−1.3 |

| Bipolar disorder (n = 3) | 0.43 | 2.58 | 0.23−29.41 |

| Personality disorder (n = 7) | 0.06 | 4.1 | 0.87−19.31 |

| Other (n = 6) | 0.99 | 1.01 | 0.11−8.99 |

| Benzodiazepine use (n = 72) | 0.01 | 3.11 | 1.4−6.88 |

| Recent user (n = 44) | 0.01 | 4.84 | 2.14−10.93 |

| Recent imprisonment (n = 12) | 0.02 | 4.12 | 1.22−13.97 |

| On OST (n = 52) | 0.01 | 4.23 | 1.9−9.43 |

| Cirrhosis (n = 112) | 0.07 | 0.5 | 0.23−1.08 |

| Decompensated cirrhosis (n = 22) | 0.36 | 1.94 | 0.46−8.2 |

| Treatment-naïve patient (n = 228) | 0.01 | 3.06 | 1.25−7.52 |

| HIV (n = 58) | 0.10 | 0.38 | 0.11−1.27 |

| Alcohol use | |||

| More than 30 g/day (n = 82) | 0.52 | 0.77 | 0.34−1.73 |

| More than 80 g/day (n = 64) | 0.73 | 0.86 | 0.37−2.01 |

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; OST: opioid substitution therapy; PWID: people who inject drugs.

Patients lost to follow-up were mostly male (95.2%), although differences compared to patients not lost to follow-up were not significant (86%; p = 0.07). No significant age differences were seen between the two groups. Psychiatric disease was present in 54.8% of patients lost to follow-up versus 38.9% of patients not lost to follow-up. Having a diagnosis of this nature, however, was not associated with a higher risk of loss to follow-up, although according to the univariate analysis, anxiety disorder did increase it by four times, just as benzodiazepines increased it threefold.

Of patients lost to follow-up, 54.8% were on OST (versus 22.3% of patients not lost to follow-up), representing a steeply increased (more than four times higher) risk of loss to follow-up. Similarly, 36.4% of recent users were lost to follow-up (versus 10.6% of past users), with a nearly five times higher risk.

There was also greater loss to follow-up of treatment-naïve patients and patients who had been in prison in the past five years. No differences were found in patients with cirrhosis, patients with HIV or alcohol users.

DiscussionAlthough HCV treatment has proven effective in patients with PWID, studies and meta-analyses on the same sample have yielded very mixed results, with eradication rates ranging from 63%17 to 95%–100%.18,19

There does seem to be a consensus, as shown by our study, that the apparently worse outcomes of HCV treatment seen in these subjects is due to loss to follow-up. The eradication rates observed in this study were significantly lower than in prior series for the general population,20–22 although once patients lost to follow-up were excluded from the analysis, similar results were obtained (an SVR12 of 96.21%). For this reason, it is essential to achieve suitable adherence to treatment.

The relationship between psychiatric disease and HCV infection is well known, although the literature on how it influences treatment in PWID is limited. Psychiatric comorbidity, predominantly depression, anxiety and schizophrenia, is high in patients with HCV and PWID (50%–60%); similarly, HCV infection tends to be present at higher rates among patients with mental and psychiatric disorders.15 In addition, patients with end-stage liver disease due to HCV infection usually are more depressed and have more mood disorders than patients with said disease due to other causes.23 In our study, rates of psychiatric disorders in PWID were consistent with the studies cited above, and having anxiety disorder was associated with lower HCV treatment effectiveness in PWID due to greater loss to follow-up, as has been demonstrated in studies on treatment of other diseases.24 Analogously, benzodiazepine use was seen to be related to loss to follow-up, though this was probably due to high rates of use of these drugs by patients with anxiety. The presence of psychiatric disease and loss to follow-up has traditionally represented a reason for exclusion from treatment due to decreased effectiveness.

DAAs have been widely shown to be safe and effective without requiring any specific dose adjustment or resulting in a decrease in either adherence or rates of SVR with the latest DAA treatments.3,4,25 However, in some registries, effectiveness in patients on OST remains lower than in individuals not on OST due to greater loss to follow-up,26 as was plain to see in our sample. We believe that this could be due to these patients' diagnosis of "substance abuse disorder" masking other psychiatric disorders, together with the high proportion of patients with a diagnosis of anxiety disorder among those on OST, and probably also limited awareness with respect to HCV infection on the part of these subjects.

In addition, those who had used parenteral drugs in the past three years and those who had been in prison in the past five years showed lower rates of adherence to treatment, greater loss to follow-up and, therefore, worse outcomes; these findings were consistent with other data series.15,27

Ultimately, this study demonstrated the importance of achieving suitable adherence to treatment in PWID patients, especially in recent users and those on OST, and highlighted the vital nature of a conducting a suitable psychiatric assessment and closer follow-up in these subjects. At present, no clinical guidelines justify delaying or impeding treatment in these patients and none require suspension of the use of these or of OST.20–22

Measures such as multidisciplinary support,28 financial incentivisation,29 telemedicine,30 needle and syringe programmes, rooms for supervised use, and primary care3,25 have been shown to increase this adherence and therefore would help to achieve higher rates of remission of infection. However, actual implementation of these interventions remains low; for this reason, they should continue to be pursued in order to ultimately achieve eradication of the virus in this group, which is considered vulnerable and which features the patients with the highest rates of infection transmission as well as the highest rates of morbidity and mortality due to liver disease.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from public, private or non-profit organisations.

AuthorsJC Fernández de Cañete: literature review; research process; statistical analysis; drafting and editing of original article.

JM Moreno: study design; protocol; study management.

MA García and A Mancebo: data collection.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Fernández de Cañete Camacho JC, Mancebo Martínez A, García Mena MA, Moreno Planas JM. Influencia de los trastornos psiquiátricos y la terapia de sustitución con opiáceos en el tratamiento del virus de la hepatitis c con antivirales de acción directa en usuarios de drogas por vía parenteral. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;45:265–273.