The emergence of highly tolerable, effective, and shorter duration direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) regimens offers the opportunity to simplify hepatitis C virus management but medical costs are unknown. Thus, we aimed to determine the direct medical costs associated with a combo-simplified strategy (one-step diagnosis and low monitoring) to manage HCV infection within an 8-week glecaprevir/pibrentasvir (GLE/PIB) regimen in clinical practice in Spain.

Patients and methodsHealthcare resources and clinical data were collected retrospectively from medical charts of 101 eligible patients at 11 hospitals. Participants were adult, treatment naïve subjects with HCV infection without cirrhosis in whom a combo-simplified strategy with GLE/PIB for 8 weeks were programmed between Apr-2018 and Nov-2018.

ResultsThe GLE/PIB effectiveness was 100% (CI95%: 96.2–100%) in the mITT population and 94.1% (CI95%: 87.5–97.8%) in the ITT population. Three subjects discontinued the combo-simplified strategy prematurely, none of them due to safety reasons. Five subjects reported 8 adverse events, all of mild-moderate intensity. Combo-simplified strategy mean direct costs were 754.35±103.60€ compared to 1689.42€ and 2007.89€ of a theoretical 12-week treatment with 4 or 5 monitoring visits, respectively; and 1370.95€ and 1689.42€ of a theoretical 8-week with 3 or 4 monitoring visits, respectively. Only 4.9% of the subjects used unexpected health care resources.

Conclusions8-week treatment with GLE/PIB combined with a combo simplified strategy in real-life offers substantial cost savings without affecting the effectiveness and safety compared to traditional approaches.

La aparición de regímenes antivirales de acción directa altamente tolerables, eficaces y de corta duración permite simplificar el manejo de la hepatitis C, pero los costes médicos se desconocen. Así, se pretende determinar los costes médicos directos asociados a una estrategia simplificada (diagnóstico en un solo paso y monitorización reducida) para controlar la infección por VHC con un régimen de 8 semanas de glecaprevir/pibrentasvir (GLE/PIB) en la práctica clínica en España.

Pacientes y métodosLos recursos sanitarios y los datos clínicos se recopilaron retrospectivamente de las historias médicas de 101 pacientes elegibles en 11 hospitales. Los participantes fueron sujetos adultos, sin tratamiento previo de la infección por VHC y sin cirrosis, en los que se programó una estrategia combinada simplificada con GLE/PIB durante 8 semanas entre abril y noviembre de 2018.

ResultadosLa eficacia de GLE/PIB fue del 100% (IC 95% 96,2-100) en la población mITT y del 94,1% (IC 95% 87,5-97,8) en la población ITT. Tres sujetos suspendieron prematuramente la estrategia combinada simplificada, ninguno de ellos por razones de seguridad. Cinco sujetos reportaron 8 acontecimientos adversos de intensidad leve-moderada. Los costes directos fueron de 754,35±103,60€ frente a 1.689,42€ y 2.007,89€ de un tratamiento teórico de 12 semanas con 4 o 5 visitas de monitorización, respectivamente; y 1.370,95€ y 1.689,42€ de un tratamiento teórico de 8 semanas con 3 o 4 visitas de monitorización, respectivamente. El 4,9% de los sujetos utilizaron recursos de atención médica inesperados.

ConclusionesEn la vida real, el tratamiento de 8 semanas con GLE/PIB junto con una estrategia simplificada ofrece ahorros sustanciales de costos, sin afectar la eficacia y seguridad, en comparación con abordajes tradicionales.

The development of combination treatments comprising all oral, interferon-free, direct-acting antiviral (DAA) drugs has substantially improved the efficacy and safety of HCV therapy. Recommended treatments are associated with high rates of sustained virological response at post-treatment week 12 (SVR12), low risk of HCV drug resistance, and treatment durations as short as 8 weeks.1 The fixed-dose combination of GLE/PIB administered orally, once-daily, for 8 weeks is a pangenotypic regimen indicated for the treatment of HCV infected patients with compensated liver disease (with or without cirrhosis) without prior HCV therapy.2

The availability of these simple and efficacious pangenotypic regimens has led the World Health Organization to recommend the use of pangenotypic regimens to support the global campaign to eliminate HCV infection by 2030.3

The diagnosis of HCV infection has also been improved and the determination of antibodies and viral load in the same sample, in a single step, is now possible.4,5 A recent survey performed among public and private Spanish hospitals showed that, in 2019, reflex testing was performed by 89% of the centers, compared to 31% in 2017.6

The combination of a single step diagnosis with a low monitoring strategy and a short duration (8-weeks) pangenotypic regimen simplifies the HCV infection management and might reduce its costs. This would increase the resources available to treat more HCV patients, and thus contributing to the aim of the WHO of eliminating HCV infection as a public health problem by 2030. Thus, we aimed to determine the non-pharmacological direct medical costs associated with a combo-simplified strategy (one-step diagnosis and low monitoring) to manage HCV infection within an 8-week GLE/PIB regimen in clinical practice in Spain. Additionally, we aimed to assess the effectiveness and safety of the 8-week GLE/PIB, and to explore the non-healthcare costs and the satisfaction of HCV patients with the combo-simplified strategy.

Patients and methodsThis is a non-interventional retrospective and cross-sectional, national, multicenter study carried out in 11 hospitals of the Spanish National Health System from June to November 2019. Sites were selected if patient data could be provided and the combo-simplified strategy had been implemented as standard of care for at least six months before the beginning of the study. Inclusion criteria required patients to be older than 18 years, diagnosed with chronic HCV infection in a single step process (consisting of the testing of HCV serology and viremia on the same blood sample),6–8 to be HCV-treatment naïve, and to not have cirrhosis (determined by APRI <1 and/or FIB-4 <1.45 and/or FibroScan <12.5kPa). In addition, patients must have initiated an 8-week GLE/PIB regimen between April and November 2018, and planned to be managed with a low monitoring strategy (consisting of a baseline visit for diagnosis and a monitoring visit 12 weeks post-treatment).8 It is of note that a patient might have had other unexpected/not scheduled visits. The protocol established that the patients were going to be randomly selected in each participant center. However, due to the limited number of potential patients, all patients fulfilling the selection criteria were invited to participate in the study per chronological order. One written informed consent was requested for retrospective data collection and another for a structured survey about patient's satisfaction with the combo-simplified strategy.

The study was conducted in accordance with ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committees of Hospital La Paz (Madrid, Spain) on 6th February 2019; and Hospital General of Segovia (Segovia, Spain) on 7th May 2019. The Ethic Committees of the additional hospitals were notified following the Spanish legislation.

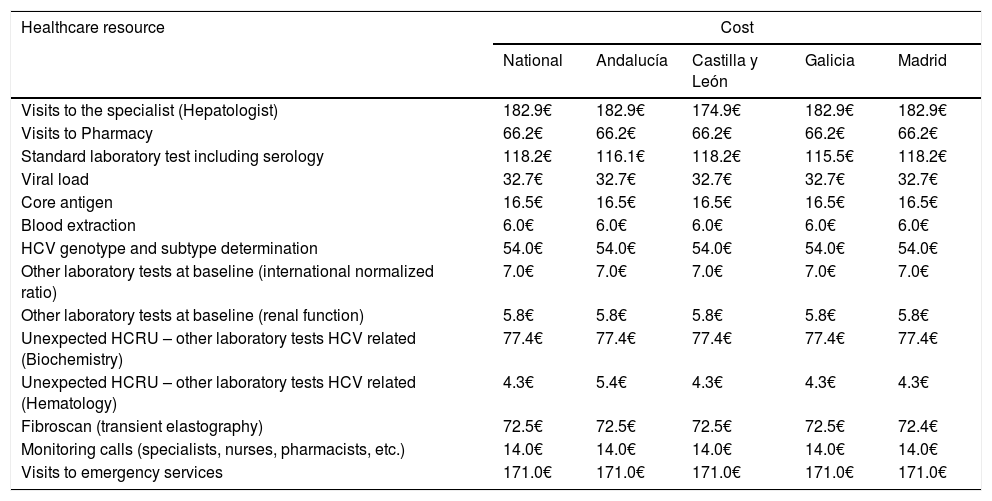

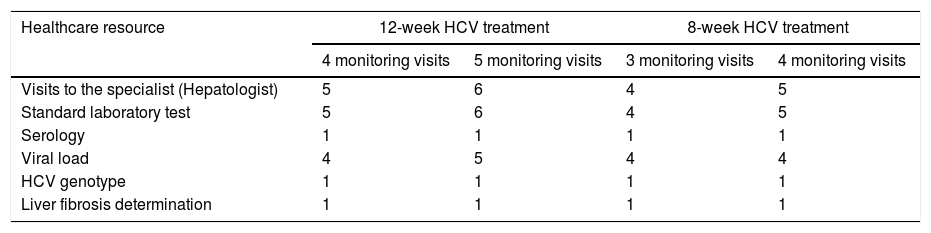

The primary endpoint was the average of the overall total non-pharmacological direct costs (other than DAA HCV cost, unrelated-HCV costs and the costs of the management of AEs unrelated to the 8-week GLE/PIB treatment) associated with the combo-simplified strategy from diagnosis to the last monitoring visit. Costs were calculated considering the expected use of healthcare resources [number of visits to the specialist and to the pharmacy (maximum two visits to the pharmacy were considered expected), the laboratory tests performed, and the additional support action considered standard of care at specific sites (monitoring calls or any other measures that were performed mainly to assess treatment adherence and safety)]. Unexpected healthcare resources were hospital visits, hospital admissions and extra laboratory tests or diagnostic tests. Costs were determined using regional costs published in Oblikue database.9 In case the information was not available for a specific region, a mean cost was calculated based on the available regional costs or the costs published by Instituto Carlos III.10 All costs were updated according to the inter-annual general Consumer Price Index (CPI) published by the National Institute of Statistics during the month of January-February 2019.11 Additionally, this information was used to estimate the theoretical non-pharmacological direct costs of a 12-week HCV treatment with traditional diagnosis and 4 or 5 monitoring visits, and the theoretical non-pharmacological direct costs of an 8-week regimen with traditional diagnosis and 3 or 4 monitoring visits. The costs of the healthcare resources used are shown in Table 1. Healthcare resources imputed to a 12-week treatment with traditional diagnosis and 4 or 5 monitoring visits and those imputed to an 8-week regimen with traditional diagnosis and 3 or 4 monitoring visits are shown in Table 2.

Costsa of healthcare resources, expected, unexpected or related to the standard of care, at national level and per region.

| Healthcare resource | Cost | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National | Andalucía | Castilla y León | Galicia | Madrid | |

| Visits to the specialist (Hepatologist) | 182.9€ | 182.9€ | 174.9€ | 182.9€ | 182.9€ |

| Visits to Pharmacy | 66.2€ | 66.2€ | 66.2€ | 66.2€ | 66.2€ |

| Standard laboratory test including serology | 118.2€ | 116.1€ | 118.2€ | 115.5€ | 118.2€ |

| Viral load | 32.7€ | 32.7€ | 32.7€ | 32.7€ | 32.7€ |

| Core antigen | 16.5€ | 16.5€ | 16.5€ | 16.5€ | 16.5€ |

| Blood extraction | 6.0€ | 6.0€ | 6.0€ | 6.0€ | 6.0€ |

| HCV genotype and subtype determination | 54.0€ | 54.0€ | 54.0€ | 54.0€ | 54.0€ |

| Other laboratory tests at baseline (international normalized ratio) | 7.0€ | 7.0€ | 7.0€ | 7.0€ | 7.0€ |

| Other laboratory tests at baseline (renal function) | 5.8€ | 5.8€ | 5.8€ | 5.8€ | 5.8€ |

| Unexpected HCRU – other laboratory tests HCV related (Biochemistry) | 77.4€ | 77.4€ | 77.4€ | 77.4€ | 77.4€ |

| Unexpected HCRU – other laboratory tests HCV related (Hematology) | 4.3€ | 5.4€ | 4.3€ | 4.3€ | 4.3€ |

| Fibroscan (transient elastography) | 72.5€ | 72.5€ | 72.5€ | 72.5€ | 72.4€ |

| Monitoring calls (specialists, nurses, pharmacists, etc.) | 14.0€ | 14.0€ | 14.0€ | 14.0€ | 14.0€ |

| Visits to emergency services | 171.0€ | 171.0€ | 171.0€ | 171.0€ | 171.0€ |

Healthcare resources imputed to HCV treatments with traditional management according to treatment duration and number of theoretical monitoring visits.a

| Healthcare resource | 12-week HCV treatment | 8-week HCV treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 monitoring visits | 5 monitoring visits | 3 monitoring visits | 4 monitoring visits | |

| Visits to the specialist (Hepatologist) | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 |

| Standard laboratory test | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 |

| Serology | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Viral load | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| HCV genotype | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Liver fibrosis determination | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Secondary endpoints included the rate of effectiveness of the 8-week GLE/PIB defined as rate of patients achieving sustained virologic response at week 12 (HCV RNA below lower level of quantification 12 weeks after the end of treatment), the number deviations from the theoretical low monitoring strategy and the number of patients not completing the combo-simplified strategy, the description of the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the patients, the identification of direct non-medical costs determinants, and the incidence of adverse events reported by the patients.

As exploratory endpoints, the study included the assessments of the indirect costs and the patient's satisfaction with the combo-simplified strategy.

The statistical analyses were performed in the Intent-to-treat (ITT) population which included those patients that fulfilled all the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria. Additionally, the effectiveness of treatment was analyzed in the modified intent-to-treat (mITT) population; in this population, patients from the ITT population who did not have a response due to other criteria different to virological reasons, i.e. lost to follow-up and/or other reasons (not-specified) were excluded.

Continuous variables are presented as mean, standard deviation (SD), median, first and third quartiles (Q1; Q3) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI), as appropriate. Shapiro–Wilk test was used to check whether the measure deviates from a normal distribution. Categorical variables are presented by using frequencies and percentages.

A logistic regression model was used to identify possible sociodemographic and clinical differences between patients with an effective combo-simplified management and those who had deviations from theorical combo-simplified management with age, sex, race, height, weight and the questions of the structured survey as dependent variables (place of residence, marital status, with whom did the patient live, educational level and employment status). Analyses were conducted using 2-sided test and a significance level of 0.05. Odds ratios and their 95% Wald confidence intervals were calculated and showed.

An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to identify determinants of direct non-medical cost, setting direct non-medical costs as dependent variable, and the sociodemographic and clinical variables age, drug use, and fibrosis as explanatory variables

A significance level of 0.05 for all tests in contrast was used.

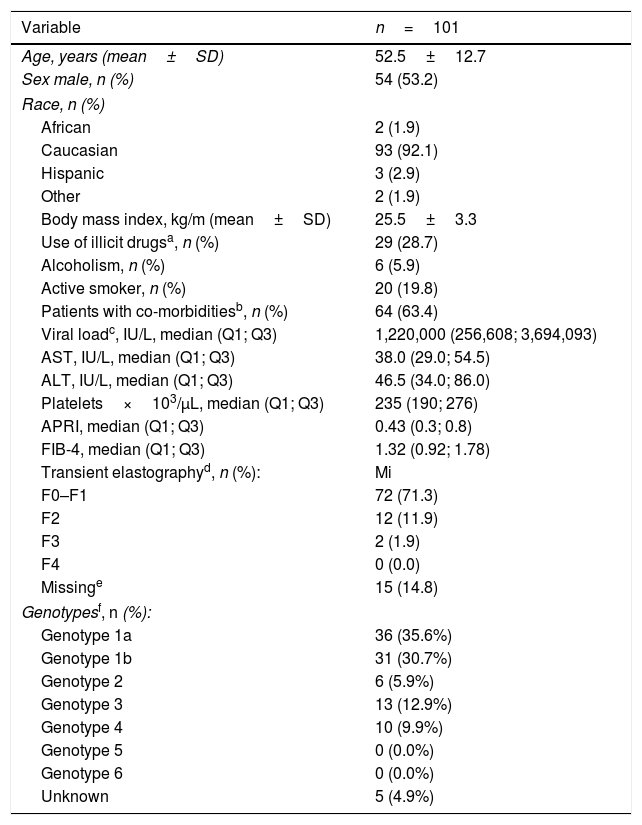

ResultsOne hundred and one subjects were enrolled at 11 centers from 4 Spanish autonomous regions. Mean patient's age was 52.5±12.7 years, 54% were men, 63.3% were infected with HCV genotype 1 and 12.9% with HCV genotype 3, 71.3% had F0-F1 fibrosis, and the median of FIB 4 was 1.3. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 3.

Clinic-demographic characteristics of the patients at baseline.

| Variable | n=101 |

|---|---|

| Age, years (mean±SD) | 52.5±12.7 |

| Sex male, n (%) | 54 (53.2) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| African | 2 (1.9) |

| Caucasian | 93 (92.1) |

| Hispanic | 3 (2.9) |

| Other | 2 (1.9) |

| Body mass index, kg/m (mean±SD) | 25.5±3.3 |

| Use of illicit drugsa, n (%) | 29 (28.7) |

| Alcoholism, n (%) | 6 (5.9) |

| Active smoker, n (%) | 20 (19.8) |

| Patients with co-morbiditiesb, n (%) | 64 (63.4) |

| Viral loadc, IU/L, median (Q1; Q3) | 1,220,000 (256,608; 3,694,093) |

| AST, IU/L, median (Q1; Q3) | 38.0 (29.0; 54.5) |

| ALT, IU/L, median (Q1; Q3) | 46.5 (34.0; 86.0) |

| Platelets×103/μL, median (Q1; Q3) | 235 (190; 276) |

| APRI, median (Q1; Q3) | 0.43 (0.3; 0.8) |

| FIB-4, median (Q1; Q3) | 1.32 (0.92; 1.78) |

| Transient elastographyd, n (%): | Mi |

| F0–F1 | 72 (71.3) |

| F2 | 12 (11.9) |

| F3 | 2 (1.9) |

| F4 | 0 (0.0) |

| Missinge | 15 (14.8) |

| Genotypesf, n (%): | |

| Genotype 1a | 36 (35.6%) |

| Genotype 1b | 31 (30.7%) |

| Genotype 2 | 6 (5.9%) |

| Genotype 3 | 13 (12.9%) |

| Genotype 4 | 10 (9.9%) |

| Genotype 5 | 0 (0.0%) |

| Genotype 6 | 0 (0.0%) |

| Unknown | 5 (4.9%) |

Of them, 22 subjects were past illicit drug users and had not taken illicit drugs 6 months prior to HCV diagnosis.

Co-morbidities presented in more than 1 patient: hypertension (n=6), generalized anxiety (n=8), hypothyroidism (n=7), diabetes mellitus (n=5), dyslipidemia (n=5), gastroesophageal reflux disease (n=4), asthma (n=4), insomnia (n=3), generalized pain (n=3), rheumatoid arthritis (n=3), osteoporosis (n=2), benign prostatic hyperplasia (n=2), obesity (n=2).

Ninety-seven subjects completed the 8-week treatment with GLE/PIB. Only 3 subjects (2.9%) discontinued the combo-simplified strategy prematurely; reasons for premature discontinuation of the combo-simplified strategy were lack of adherence in one subject, a job-related problem in another subject, and unknown in the third. The completion information was missing in another subject. Viral load measurements 12 weeks post-treatment was obtained in 95 (94.1%) patients. The GLE/PIB effectiveness in the ITT population was 94.1% (CI95%: 87.5–97.8%). When mITT population was used, the GLE/PIB effectiveness was 100% (CI95%: 96.2–100%).

Twenty-two subjects (21.8%) (CI95%: 14.2–31.1%) completed the combo-simplified strategy without deviations, and 79 subjects (78.2%) (CI95%: 68.9–85.8%) had deviations from the strategy; of them, 74 (73.3%) had additional expected HCRU and 5 (4.9%) additional unexpected HCRU. The expected HCRU corresponded to additional visits to the Pharmacy Service (63 subjects required one additional visit and 1 subject required 2 additional visits) and standard of care calls (15 subjects). Of those subjects requiring unexpected health care resources use, 1 subject was to the Emergency Room due to allergic rhinitis, 2 subjects needed additional ultrasounds, 1 subject was to the Emergency Room and required hospitalization due to dyspnea, and additional ultrasounds, and 1 subject needed an additional transient elastography. No sociodemographic or clinical subjects’ characteristics impacted on the logistic regression model used to identify possible differences between subjects who follow the combo-simplified management without deviations and those who had deviations from this strategy.

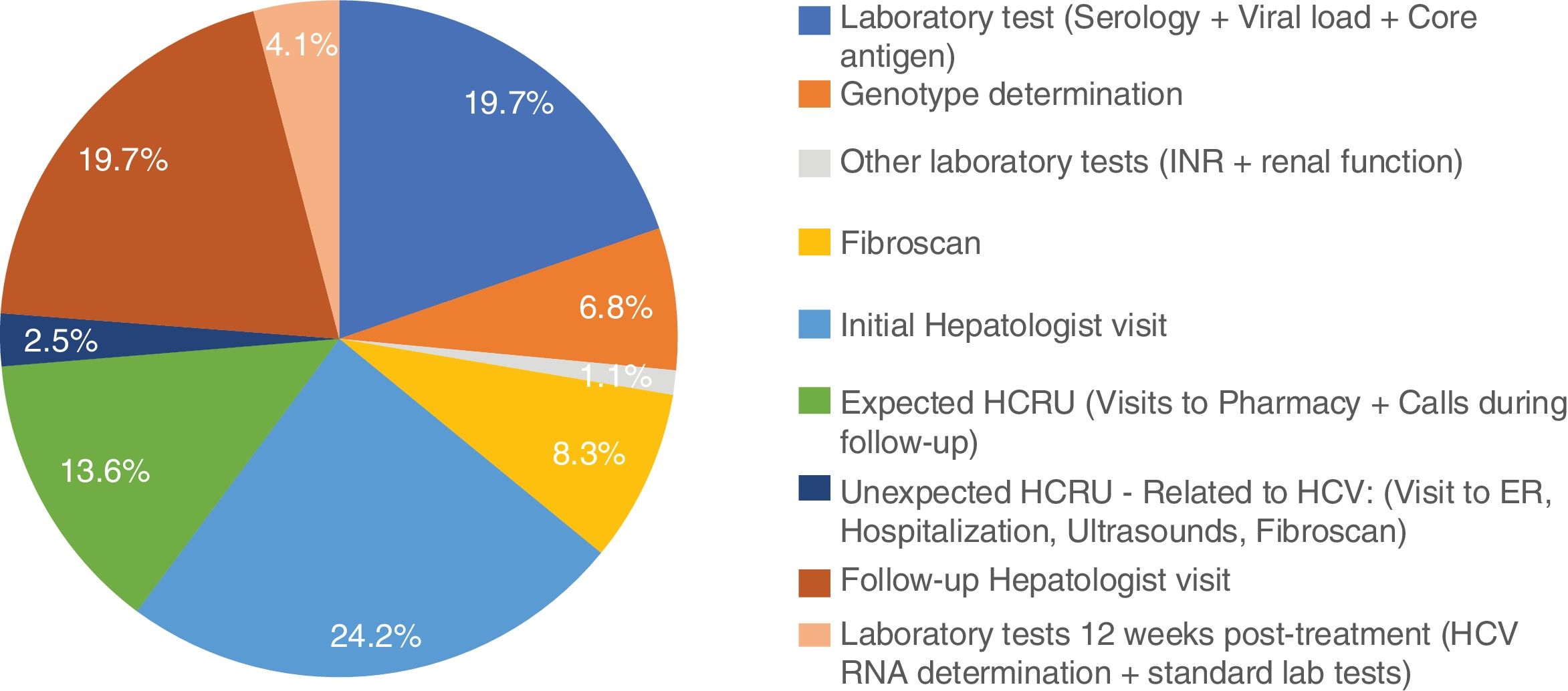

Excluding from the analysis one subject with outlier results (the subject was hospitalized for 9 days due to dyspnea), mean non-pharmacologic direct costs of the combo-simplified strategy were 754.3±103.6€. When this subject was included, the combo-simplified strategy mean non-pharmacologic direct costs were 837.9±845.6€. Almost 44% of the costs corresponded to visits to the specialists (basal/diagnosis and monitoring visits) and 30.6% to HCV laboratory tests (serology, core antigen, viral load, and genotyping). No determinants of direct medical cost were found with the ANCOVA model. The distribution of the costs per patient are shown in Fig. 1.

The theoretical non-pharmacological direct cost of a 12-week treatment with traditional diagnosis and 4 or 5 monitoring visits was 1689.4€ and 2007.9€ per patient, respectively; and the theoretical non-pharmacologic direct cost of an 8-week regimen with traditional diagnosis and 3 or 4 monitoring visits was 1370.9€ and 1689.4€ per patient, respectively. Comparing the real combo-simplified strategy with a theoretical traditional management, the combo-simplified strategy provides savings of 616.6€–935.1€ (for 8-week treatments comparisons) and 935.1€–1253.5€ (for 12-week treatments comparisons).

Five patients had a total of 8 adverse events (AEs); of them, 5 were of mild intensity [polycythemia, diarrhea, urinary tract infection, and headache (2×)] and 3 were of moderate intensity (pulmonary hypertension, rhinitis allergic and sleep apnea syndrome). One of these patients was hospitalized due to dysnea. There were no other hospitalizations. Only diarrhea and headaches were considered possibly related to GLE/PIB regimen. No other serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported.

Only 25 patients answered the structured survey; of them, 3 patients reported productivity losses; one subject missed 59 days, other missed 2 days, and the third one missed 6h. Mean indirect costs due to absenteeism from the initial to the last visit at 12 weeks post-treatment was 197.08±939.4€. Out of the 25 subjects that answered the structured survey, the medical care provided met their needs “Absolutely” in 21 subjects, and “Quite a lot” in 4 subjects. Six subjects were “Satisfied” and 19 “Very satisfied” with the medical services they had received. Finally, 21 subjects were “Satisfied” and 4 “Very satisfied” with the access to specialized care.

DiscussionThe elimination of HCV infection as a public health problem became an ambitious target that the WHO intends to achieve by 2030.3 The complexity of this objective lies, on one hand, in the difficulty of coordinating different stakeholders (competent authorities, payors, Healthcare providers, patients, etc.) to move toward universal programs of prevention, diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of HCV infected patients and, on the other hand, the financial resource limitations to implement those programs. A recent study carried out to assess the progress made in 45 high-income countries toward meeting the WHO's target showed that only 9 countries are on track toward achieving this goal by 2030; Spain was among them, and the estimated year for HCV elimination in Spain was 2023.12

The availability of effective pangenotypic regimens is one of the key elements for achieving HCV elimination as patients chronically infected with HCV can now be effectively treated.13 In our study, the effectiveness of the combo-simplified strategy was 100% considering the mITT population and 94.1% considering the ITT population. This is in line with the efficacy observed in clinical trials in which a traditional 8-week GLE/PIB treatment has shown sustained virological response rates ranging between 92.0% and 100% in patients with HCV genotype 1–6, without cirrhosis14–16 or with compensated cirrhosis17,18 or in other special populations like HIV-coinfected patients19 and patients with renal impairment.20 Our results are also in line with a recently published meta-analysis in which GLE/PIB was administered to 12,531 adults in a real-world setting. The SVR12 rate for the 3657 treatment-naïve patients without cirrhosis that received GLE/PIB for 8 weeks was 99.3% in the mITT population, defined as ITT population excluding patients who did not achieve SVR12 for reasons other than virologic failure.21 Nevertheless, the results of a recently published phase 3 clinical trial have shown that the efficacy of GLE/PIB in non-cirrhotic HCV patients with a simplified monitoring schedule did not achieve non-inferiority in comparison to the standard monitoring.22 In the ITT population, SVR12 was 92% in the simplified and 95% in the standard arm, a difference mainly driven by a higher proportion of patients with non-virological failure (death, discontinuation and loss to follow-up or missing HCV RNA) in the simplified arm (6%) compared with the standard arm (3%). Differently from our study, HIV co-infected patients and patients with severe fibrosis participated in this clinical trial. The authors suggested that patients without cirrhosis or adherence concerns may benefit of a simplified treatment monitoring.22 Thus, we consider necessary a thorough assessment of the patient's potential treatment compliance before assigning the patient to a simplified monitoring schedule.

Traditionally, patients with chronic HCV required close monitoring, incurring higher costs per patient and visits. In 2017, with the DAAs available at that time, at treatment initiation the guidelines recommended measurements of HCV RNA plasma or serum levels and genotyping as well as general laboratory tests. HCV RNA measurements were also recommended 12 weeks post-treatment.8 As in general practice HCV RNA measurements were also common at week 4 and at the end of HCV treatment, we calculated the non-pharmacologic costs of theoretical scenarios with 3–5 monitoring visits. Thus, with the available sources of information,9,10 we estimated that, in Spain, those costs ranged from 1370.9€ per patient of a traditional 8-week regimen with 3 visits to 2007.9€ per patient of a traditional 12-week treatment with 5 monitoring visits. However, the combination of an 8-week GLE/PIB regimen with a diagnosis-monitoring simplified strategy that included 2 monitoring visits reduced these non-pharmacological costs to a mean of 754.3€, thus providing a substantial cost saving in the HCV management burden. Regarding the deviations from the theorical combo-simplified management that impact in the non-pharmacologic costs, it is striking that most of them corresponded to additional visits to the Pharmacy Service. We consider that this is an area of improvement as an 8-week regiment should contribute to minimize these visits. But, the combo-simplified strategy offers not only potential non-pharmacological cost savings, but also a reduction in the burden of care, thus allowing hepatologists to treat more HCV patients or to dedicate technical and human healthcare resources to treat and manage other pathologies.

The safety profile of the 8-week GLE/PIB treatment in our study was similar to that observed in the above mentioned meta-analysis in which AEs were reported in 17.7% of the patients, being pruritus (4.7%), fatigue (4.2%) and headache (2.7%) the most frequently reported. SAEs were reported in 1.0% of the patients in the meta-analysis.21 In our study, only 4.9% of the patients reported AEs and none of them was considered serious.

Data to assess the exploratory endpoints indirect costs and patients’ satisfaction with the combo-simplified strategy was obtained only in a 25% of the participant patients; therefore, no conclusive results have been obtained.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, it is important to note that the study was designed in 2017 and carried out in 2018, when 4 or 5 monitoring visits in HCV patients treated with DAAs was clinical practice in most Spanish hospitals. Nowadays, the number of monitoring visits; therefore, comparisons with current standard approaches would not lead to such a substantial savings. In any case, GLE/PIB is still the only pangenotipic 8-week DAA regimen for treatment naïve HCV patients. Secondly, the hospitals participating in our study may not represent the whole Spanish hospitals, as only hospitals that had already implemented a simplified HCV patients’ management were selected, and this simplified strategy was not widely use in the Spanish hospitals at the time the study was carried out. Another limitation, inherent to retrospective studies, is the patients’ selection bias. Due to the circumstances already mentioned, the patients were not randomly selected; however, all available candidates with no exception, were invited to participate in the study, minimizing this potential bias. In our study HIV-coinfected patients or patients with chronic renal failure did not participate; thus, our results could not be extrapolated to those special patient populations. The study did not include a control group and the cost savings have been calculated with theoretical scenarios that might differ from the real clinical practice. Regarding the structured survey about patient's satisfaction with the combo-simplified strategy, a recall bias was unlikely as the elapsed period of time between the end of treatment and the survey was not long. However, as above mentioned, due to the small number of respondents, the results were not conclusive. Finally, the costs of some resources were not available in all regions. As in those cases a national mean cost was calculated based on the available regional costs or the costs published by Instituto Carlos III, therefore we do not expect a significant impact on our results.

One of the strengths of our study is that we have considered all relevant variables related to the non-pharmacologic costs of the HCV patient management. In addition, different from many other studies in which costs assessments have been performed using theoretical data based on the prevalence of the disease or the literature review, our study was a real-life study and the results obtained can be considered closer to our healthcare reality.

ConclusionTreatment of chronic HCV infection with GLE/PIB for 8 weeks allows to implement a simplified strategy in the patient evaluation and monitoring without affecting the effectiveness and safety observed with traditional strategies in other real-life studies, and led to substantial cost savings when compared with traditional regimens that were the standard of care in 2018 in the Spanish hospitals.

Savings obtained with the use of simplified strategies in the HCV infection management would let more patients to be successfully treated and this might contribute to reaching the WHO's target of eliminating HCV as a public health problem by 2030.

Conflict of interest and source of fundingTurnes Vázquez J. has received speaker and consulting fees from AbbVie and Gilead, and grants from Gilead.

Rincón Rodríguez D. has received consulting fees from Abbvie.

Calleja J.L. has received consulting and speaker fees from Abbvie, Gilead Sciences and MSD.

Delgado Blanco M. has received consulting and training fees from Abbvie, Gilead and MSD.

Rosales Zabal J.M. has nothing to disclose.

Andrade Bellido R.J. has received Advisor and Speaker Bureau: Abbvie, Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, and Research Grants from Willmar Schwabe GmbH & Co, Gedeon Richter/Preglem S.A.

Manzano Alonso M.L. has nothing to disclose.

Salmerón Escobar J. has nothing to disclose.

López Garrido M.A. has nothing to disclose.

Calvo Sánchez M. has nothing to disclose.

Gómez Camarero J. has received speaker fees from AbbVie.

Molina Pérez E. has nothing to disclose.

Nubia Frias Y. has nothing to disclose.

Galvez Fernandez R. has nothing to disclose.

Vallejo-Serna N. has nothing to disclose.

París S is AbbVie employee and may have AbbVie stocks.

Santos de Lamadrid R. is AbbVie employee and may have AbbVie stocks.

Olveria A. has received speaker and consulting fees and grants from AbbVie, Gilead and MSD.

AbbVie sponsored and financed the study; contributed to the design; participated in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in writing, reviewing, and approval of the final version. No honoraria or payments were made for authorship.

We thank Pivotal, S.L.U. (Madrid, Spain) for the statistical analysis, and Angel Burgos at Pivotal, S.L.U. for editing the manuscript and editorial writing assistance. These services were funded by AbbVie S.L.U.