To evaluate the performance of the quantitative markers of hepatitis B core-related antigen (HBcrAg) and anti-hepatitis B core antigen antibodies HbcAb versus hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and hepatitis B virus DNA (HBV DNA) in predicting liver fibrosis levels in chronic hepatitis B patients.

MethodsTwo hundred and fifty hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-positive and 245 HBeAg-negative patients were enrolled. With reference to the Scheuer standard, stage 2 or higher and stage 4 liver disease were defined as significant fibrosis and cirrhosis, respectively. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to evaluate the performance of the HBV markers investigated.

ResultsThe areas under the ROC curves (AUCs) of HBcrAg in predicting significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in HBeAg-positive patients (0.577 and 0.700) were both close to those of HBsAg (0.617 and 0.762) (both P> 0.05). In HBeAg-negative patients (0.797 and 0.837), they were both significantly greater than those of HBV DNA (0.723 and 0.738) (P=0.0090 and P=0.0079). The AUCs of HBcAb in predicting significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in HBeAg-positive patients (0.640 and 0.665) were both close to those of HBsAg. In HBeAg-negative patients (0.570 and 0.621), they were both significantly less than those of HBcrAg (P <0.0001 and P=0.0001). Specificity in predicting significant fibrosis and sensitivity in predicting cirrhosis in HBeAg-positive patients, using a single cut-off of HBsAg ≤5,000 IU/ml, were 76.5% and 72.7%, respectively. In HBeAg-negative patients, using a single cut-off of HBcrAg>80kU/ml, they were 85.9% and 81.3%, respectively.

ConclusionsHBsAg has good performance in predicting liver fibrosis levels in HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients, and HBcrAg has very good performance in predicting liver fibrosis levels in HBeAg-negative patients.

Evaluar el rendimiento de los marcadores cuantitativos del antígeno central de la hepatitis B (HBcrAg) y los anticuerpos contra el antígeno central de la hepatitis B (HBcAb) frente al antígeno de superficie de la hepatitis B (HBsAg) y el ADN del virus de la hepatitis B (ADN del VHB) en la predicción de los niveles de fibrosis hepática de los pacientes con hepatitis B crónica.

MétodosSe inscribieron 250 pacientes con HBsAg positivo y 245 pacientes con HBeAg negativo. Con referencia al estándar de Scheuer, la etapa patológica hepática 2 o superior y la etapa 4 se definieron como fibrosis y cirrosis significativas, respectivamente. Se utilizó la curva característica de funcionamiento del receptor (ROC) para evaluar el rendimiento de los marcadores del VHB investigados.

ResultadosLas áreas bajo la curva ROC (AUC) del HBcrAg en la predicción de la fibrosis y cirrosis significativa de los pacientes positivos para el HBeAg (0,577 y 0,700) fueron ambas cercanas a las del HBsAg (0,617 y 0,762) (ambas p > 0,05); de los pacientes negativos para el HBeAg (0,797 y 0,837) fueron ambas significativamente mayores que las del ADN del VHB (0,723 y 0,738) (p = 0,0090 y p = 0,0079); las AUC del HBcAb en la predicción de la fibrosis y cirrosis significativa de los pacientes positivos para el HBeAg (0,640 y 0,665) fueron ambas cercanas a las del HBsAg; de los pacientes negativos para el HBeAg (0,570 y 0,621) fueron ambas significativamente menores que las del HBcrAg (p < 0,0001 y p = 0,0001). La especificidad en la predicción de la fibrosis significativa y la sensibilidad en la predicción de la cirrosis de los pacientes positivos para el HBeAg, utilizando un solo corte de HBsAg ≤ 5.000 UI/mL fueron 76,5 y 72,7%, respectivamente; de los pacientes negativos para el HBeAg utilizando un solo corte de HBcrAg > 80 kU/mL fueron 85,9 y 81,3%, respectivamente.

ConclusionesEl HBsAg tiene un buen rendimiento en la predicción de los niveles de fibrosis hepática de los pacientes HBeAg positivos y negativos, mientras que HBcrAg tiene un muy buen rendimiento en la predicción de los niveles de fibrosis de los pacientes HBaAg negativos.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is still a global public health problem. Around 240 million people worldwide are infected with HBV, which causes about 600, 000 deaths per year.1,2 The main drivers of death from chronic HBV infection are hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatic decompensation, and the key link in which are the development of cirrhosis.3 Nevertheless, Chronic HBV infection may only progress and keep silent for decades until end-stage liver diseases of irreversible cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatic decompensation occur. Moreover, not all patients with chronic HBV infections will progress to end-stage liver diseases.4 Therefore, it is of great practical importance to identify those patients at risk of cirrhosis who require antiviral therapy.

Factors associated with the progression of chronic HBV infection have not been elucidated. Insufficient immune response to HBV, accompanied by quantitative changes in serum HBV markers, is the primary mechanism leading to liver injury and fibrosis progression.5,6 Therefore, quantitative serum HBV markers should theoretically be important parameters reflecting liver pathological states and guiding treatment decisions. Serum HBV markers can be divided into two categories according to the molecular attributes and detecting methods: HBV antigens and their specific antibodies, and HBV genome and its RNA transcripts.7 The quantitative HBV markers that have been commercially detected include hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis B core-related antigen (HBcrAg), hepatitis B core antibody (HBcAb), and HBV DNA. The quantitative detection of HBV RNA has been developed, but has not yet been standardized and commercialized.7,8 All of commercial quantitative HBV markers for predicting liver pathological states have been evaluated, but were rarely compared fully in the same cohort;9–28 and so far, only HBV DNA has been used in major international guidelines on the management of chronic HBV infection.29–32

To better characterize the clinical value of the quantitative HBV markers, we compared the performance of HBcrAg and HBcAb of the newer HBV markers with HBsAg and HBV DNA of the older HBV markers for predicting liver fibrosis levels in the same cohort.

MethodsStudy populationThis cross-sectional study included 495 treatment-naive Chinese patients with chronic HBV infection who underwent liver biopsy at the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center of Fudan University, China, between January 2015 and December 2017. The diagnoses of all patients were in accordance with the standard elaborated in the EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Hepatitis B Virus Infection.30

We did not include patients with HBV combined with other forms of hepatotropic virus, human immunodeficiency virus, cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus infection, and patients with drug-induced liver injuries, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (steatosis>5% of hepatocytes), significant alcohol consumption (>20g/day), Schistosoma japonicum liver disease, endocrine and metabolic diseases, and hematological diseases; we also excluded patients who had accepted therapy with interferon-alpha, nucleos(t)ides, matrine/oxymatrine, glycyrrhizinate, and traditional Chinese medicine in the last six months, and patients with poor quality of biopsy specimens (biopsy length <10mm).

EthicsThis study was approved by the independent ethics committee of Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center of Fudan University. All patients provided written consent before liver biopsy, and all clinical investigations were conducted according to the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki.

Laboratory assaysFasting blood samples were collected in the morning one day before and after liver biopsy. The serum was separated and stored at-40°C until it was measured. HBcrAg was measured using a chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay (CLEIA) in a LUMIPULSE G1200 automated analyzer (Fujirebio Diagnostics, Inc., Tokyo, Japan), and the HBcrAg kits were kindly provided by Fujirebio Diagnostics, Inc.(Tokyo, Japan); the detection range of HBcrAg is 1 to 10, 000 kU/mL, and a sample was retested at a dilution of 1: 1, 000 if HBcrAg exceeded the upper limit of detection (ULD). HBcAb was measured using a chemiluminescence microparticle immunoassay (CMIA) in a UMIC Caris200 automated analyzer (United Medical Instruments Co., Ltd, Xiamen, China), and the HBcAb kits were kindly provided by Innodx Biotech Co. Ltd. (Xiamen, China); the detection range of HBcAb is 100 to 100,000IU/mL. HBsAg and HBeAg were measured using a CMIA in an Abbott Architect I2000 automated analyzer (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, USA), and the reagents were purchased from Abbott Laboratories (Chicago, USA); the detection range of HBsAg is 0.05 to 250 IU/mL, and a sample was remeasured at a dilution of 1: 500 if HBsAg exceeded the ULD; the lower limit of detection of HBeAg is 1.0 S/CO. HBV DNA was detected using a PCR-fluorescence probing assay in a Roche LightCycler480 qPCR system (Roche Diagnostics Ltd., Rotkreuz, Switzerland), and the HBV DNA kits were purchased from Sansure Biotech Inc. (Changsha, China); the detection range of HBV DNA is 5.0×102 to 2.0×109 IU/mL.

Pathological diagnosesUltrasound-assisted liver biopsies were performed using a one-second liver biopsy needle (16G). The biopsy samples were immediately transferred into plastic tubes, snap-frozen, and processed within 36hours. The biopsy samples less than 10mm in length were excluded from this study. The liver pathological diagnoses were conducted independently by one experienced pathologist who was blinded to all serum biochemical and virological parameters. The pathological diagnoses were based on the Scheuer standard,33 in which grade is used to describe the intensity of necro-inflammation, and stage is a measure of fibrosis and architectural alteration; the grades include five levels from G0 to G4, and the stages include five levels from S0 to S4. In this study, the stage 2 or higher and stage 4 were defined as significant fibrosis and cirrhosis, respectively.

Statistical analysesMedCalc 15.8 software (MedCalc Software, Broekstraat, Mariakerke, Belgium) was used for statistical analyses and graphic productions. Pearson chi-squared test was used to compare the differences in frequencies of different liver pathological grades and stages between HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients. Independent samples Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the differences in medians of HBV markers between HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients. Fisher Z test was used to compare the differences in Spearman correlation coefficients between different HBV markers with liver pathological grade and stage. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to evaluate the validity of HBV markers in predicting significant fibrosis and cirrhosis. Paired-samples DeLong Z test was used to compare the differences in areas under ROC curves (AUCs) between different HBV markers in predicting the same levels of fibrosis. A two-sided P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

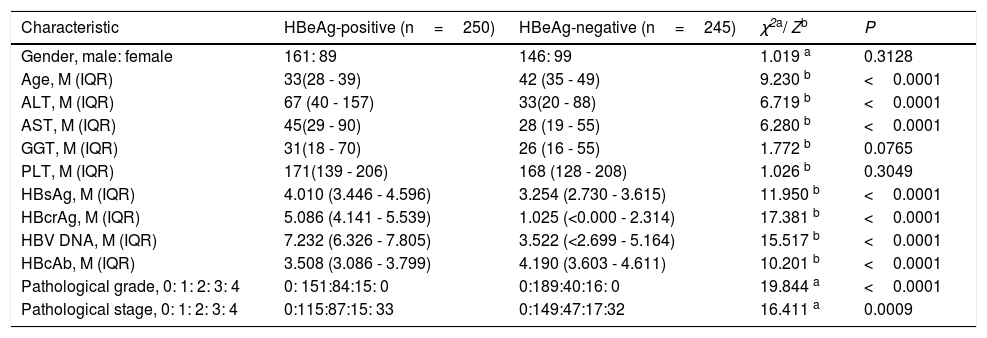

ResultsClinical, laboratory, and pathological characteristics of study populationThe clinical, laboratory and pathological data of the study population are summarized in Table 1. The frequency of significant fibrosis of HBeAg-positive patients (54.0%, 135/250) was significantly greater than that of HBeAg-negative patients (39.2%, 96/245) (x2=10.327, P=0.0013), and of cirrhosis of HBeAg-positive patients (13.2%, 33/250) was close to that of HBeAg-negative patients (13.1%, 32/245) (x2=0.008, P=0.9304).

Clinical, laboratory and pathological characteristics of study population.

| Characteristic | HBeAg-positive (n=250) | HBeAg-negative (n=245) | χ2a/ Zb | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, male: female | 161: 89 | 146: 99 | 1.019 a | 0.3128 |

| Age, M (IQR) | 33(28 - 39) | 42 (35 - 49) | 9.230 b | <0.0001 |

| ALT, M (IQR) | 67 (40 - 157) | 33(20 - 88) | 6.719 b | <0.0001 |

| AST, M (IQR) | 45(29 - 90) | 28 (19 - 55) | 6.280 b | <0.0001 |

| GGT, M (IQR) | 31(18 - 70) | 26 (16 - 55) | 1.772 b | 0.0765 |

| PLT, M (IQR) | 171(139 - 206) | 168 (128 - 208) | 1.026 b | 0.3049 |

| HBsAg, M (IQR) | 4.010 (3.446 - 4.596) | 3.254 (2.730 - 3.615) | 11.950 b | <0.0001 |

| HBcrAg, M (IQR) | 5.086 (4.141 - 5.539) | 1.025 (<0.000 - 2.314) | 17.381 b | <0.0001 |

| HBV DNA, M (IQR) | 7.232 (6.326 - 7.805) | 3.522 (<2.699 - 5.164) | 15.517 b | <0.0001 |

| HBcAb, M (IQR) | 3.508 (3.086 - 3.799) | 4.190 (3.603 - 4.611) | 10.201 b | <0.0001 |

| Pathological grade, 0: 1: 2: 3: 4 | 0: 151:84:15: 0 | 0:189:40:16: 0 | 19.844 a | <0.0001 |

| Pathological stage, 0: 1: 2: 3: 4 | 0:115:87:15: 33 | 0:149:47:17:32 | 16.411 a | 0.0009 |

M, median; IQR, Interquartile range.

ALT, alanine transferase; AST, aspartate transferase; GGT, gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase; PLT, platelet; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBcAg, hepatitis B core antigen; HBcrAg, hepatitis B core-related antigen; HBcAb, antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen; HBV DNA, hepatitis B virus DNA.

The units of measurement: age, years; ALT, AST and GGT, IU/L; PLT,×109/L; HBsAg, HBV DNA and HBcAb, log10 IU/mL; HBcrAg,log10 kU/mL.

The pathological stage was strongly positively correlated with pathological grade of both HBeAg-positive patients (rs=0.710, P<0.0001) and HBeAg-negative patients (rs=0.746, P<0.0001); and the Spearman correlation coefficient of pathological stage with pathological grade of HBeAg-positive patients was close to that of HBeAg-negative patients (Z=0.8479, P=0.3965).

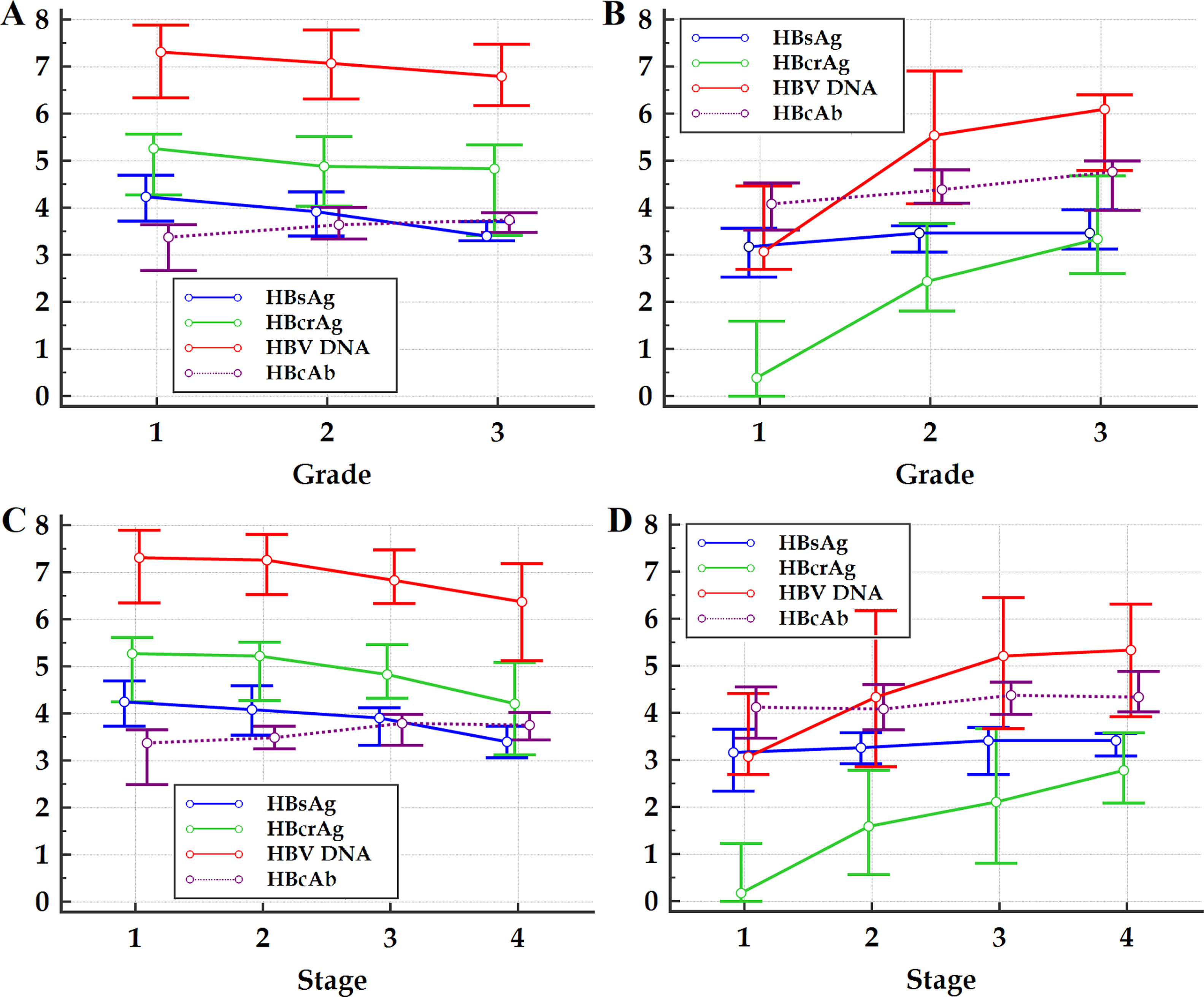

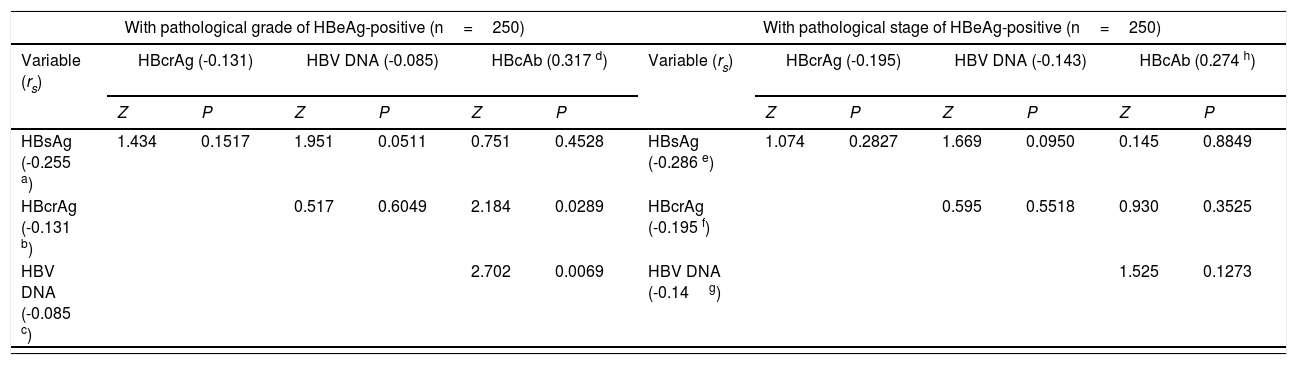

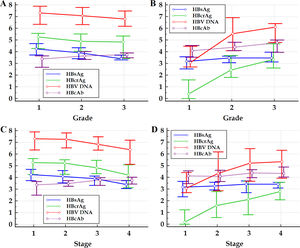

Within the frameworks of HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients, respectively, the differences in Spearman correlation coefficients between different HBV markers with liver pathological grade and stage are summarized in Table 2. The changes in medians and quartiles of HBV markers clustered by progressive pathological grades and stages are illustrated in Figure 1.

Difference comparisons in Spearman correlation coefficients between different HBV markers with liver pathological grade and stage.

| With pathological grade of HBeAg-positive (n=250) | With pathological stage of HBeAg-positive (n=250) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (rs) | HBcrAg (-0.131) | HBV DNA (-0.085) | HBcAb (0.317 d) | Variable (rs) | HBcrAg (-0.195) | HBV DNA (-0.143) | HBcAb (0.274 h) | ||||||

| Z | P | Z | P | Z | P | Z | P | Z | P | Z | P | ||

| HBsAg (-0.255 a) | 1.434 | 0.1517 | 1.951 | 0.0511 | 0.751 | 0.4528 | HBsAg (-0.286 e) | 1.074 | 0.2827 | 1.669 | 0.0950 | 0.145 | 0.8849 |

| HBcrAg (-0.131 b) | 0.517 | 0.6049 | 2.184 | 0.0289 | HBcrAg (-0.195 f) | 0.595 | 0.5518 | 0.930 | 0.3525 | ||||

| HBV DNA (-0.085 c) | 2.702 | 0.0069 | HBV DNA (-0.14g) | 1.525 | 0.1273 | ||||||||

| With pathological grade of HBeAg-negative (n=245) | With pathological stage of HBeAg-negative (n=245) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (rs) | HBcrAg (0.536) | HBV DNA (0.489) | HBcAb (0.239 l) | Variable (rs) | HBcrAg (0.535) | HBV DNA (0.404) | HBcAb (0.147 p) | ||||||

| Z | P | Z | P | Z | P | Z | P | Z | P | Z | P | ||

| HBsAg (0.179 i) | 4.593 | <0.0001 | 3.892 | 0.0001 | 0.690 | 0.4899 | HBsAg (0.128 m) | 5.153 | <0.0001 | 3.297 | 0.0010 | 0.213 | 0.8313 |

| HBcrAg (0.536 j) | 0.702 | 0.4829 | 3.903 | 0.0001 | HBcrAg (0.535 n) | 1.856 | 0.0635 | 4.940 | <0.0001 | ||||

| HBV DNA (0.489 k) | 3.201 | 0.0014 | HBV DNA (0.404 o) | 3.084 | 0.0020 | ||||||||

HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBcrAg, hepatitis B core-related antigen; HBcAb, antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen; HBV DNA, hepatitis B virus DNA.

a-pP values of Spearman correlation coefficients of HBV markers with liver pathological grade and stage:

Figure 1 Multiple variables graph of investigated HBV markers clustered by liver pathological grade (A and B) and stage (C and D) of HBeAg-positive (A and C) and HBeAg-negative (B and D) patients. HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBcrAg, hepatitis B core-related antigen; HBcAb, antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen; HBV DNA, hepatitis B virus DNA. The vertical axis represents HBsAg, HBcrAg, HBV DNA and HBcAb levels, the units of measurement of which are log10 IU/mL, log10kU/mL, log10 IU/mL and log10 IU/mL, respectively; the small circles in the scheme represent medians, and the horizontal lines above and below the small circles represent the quartiles.

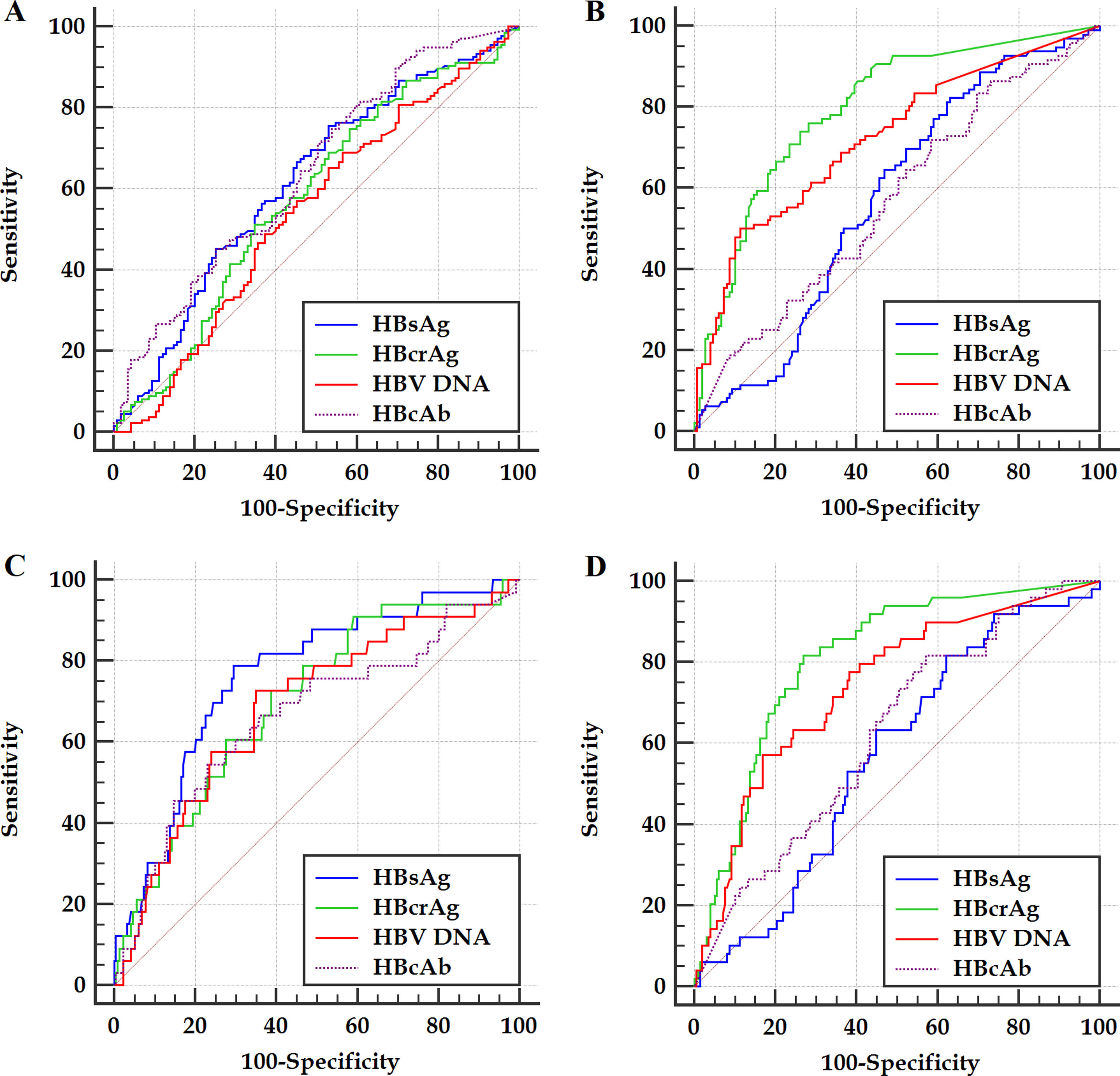

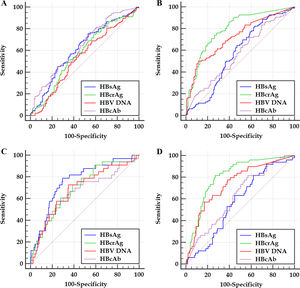

Within the frameworks of HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients, respectively, the ROC curves of the HBV markers for predicting significant fibrosis and cirrhosis are illustrated in Figure 2. The differences in AUCs between different HBV markers for predicting significant fibrosis and cirrhosis are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 2 ROC curves of investigated HBV markers for predicting significant fibrosis (A and B) and cirrhosis (C and D) of HBeAg-positive (A and C) and HBeAg-negative (B and D) patients. HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBcrAg, hepatitis B core-related antigen; HBcAb, antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen; HBV DNA, hepatitis B virus DNA.

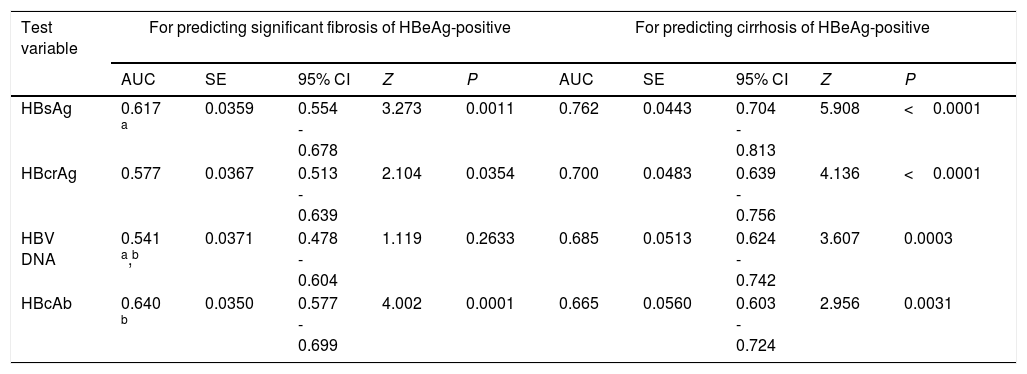

AUCs of investigated HBV markers for predicting significant fibrosis and cirrhosis.

| Test variable | For predicting significant fibrosis of HBeAg-positive | For predicting cirrhosis of HBeAg-positive | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | SE | 95% CI | Z | P | AUC | SE | 95% CI | Z | P | |

| HBsAg | 0.617 a | 0.0359 | 0.554 - 0.678 | 3.273 | 0.0011 | 0.762 | 0.0443 | 0.704 - 0.813 | 5.908 | <0.0001 |

| HBcrAg | 0.577 | 0.0367 | 0.513 - 0.639 | 2.104 | 0.0354 | 0.700 | 0.0483 | 0.639 - 0.756 | 4.136 | <0.0001 |

| HBV DNA | 0.541 a,b | 0.0371 | 0.478 - 0.604 | 1.119 | 0.2633 | 0.685 | 0.0513 | 0.624 - 0.742 | 3.607 | 0.0003 |

| HBcAb | 0.640 b | 0.0350 | 0.577 - 0.699 | 4.002 | 0.0001 | 0.665 | 0.0560 | 0.603 - 0.724 | 2.956 | 0.0031 |

| Test variable | For predicting significant fibrosis of HBeAg-negative | For predicting cirrhosis of HBeAg-negative | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | SE | 95% CI | Z | P | AUC | SE | 95% CI | Z† | P | |

| HBsAg | 0.574 c,d | 0.0366 | 0.510 - 0.637 | 2.029 | 0.0424 | 0.570 h,i | 0.0436 | 0.506 - 0.633 | 1.611 | 0.1071 |

| HBcrAg | 0.797 c,e,f | 0.0289 | 0.741 - 0.845 | 10.270 | <0.0001 | 0.837 h,j,k | 0.0273 | 0.785 - 0.881 | 12.383 | <0.0001 |

| HBV DNA | 0.723 d,e,g | 0.0335 | 0.663 - 0.779 | 6.662 | <0.0001 | 0.738 i,j,l | 0.0435 | 0.678 - 0.792 | 5.474 | <0.0001 |

| HBcAb | 0.570 f,g | 0.0374 | 0.506 - 0.633 | 1.880 | 0.0601 | 0.621 k,l | 0.0515 | 0.557 - 0.682 | 2.352 | 0.0187 |

AUC, area under ROC curve; SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval.

HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBcrAg, hepatitis B core-related antigen; HBcAb, antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen; HBV

DNA, hepatitis B virus DNA.

a − l DeLong pairwise samples Z test:

Based on binary logistic stepwise regression analyses, in which HBsAg, HBcrAg, HBV DNA and HBcAb were all the included independent variables, of HBeAg-positive patients, HBcAb and HBsAg were the only marker for predicting significant fibrosis [OR (95%CI): 2.266 (1.524-3.369)] and cirrhosis [OR(95%CI): 0.282 (0.163-0.488)], respectively; of HBeAg-negative patients, HBcrAg was the only marker for predicting both significant fibrosis [OR (95%CI): 2.282 (1.800-2.892)] and cirrhosis [OR (95%CI): 2.153 (1.628-2.848)].

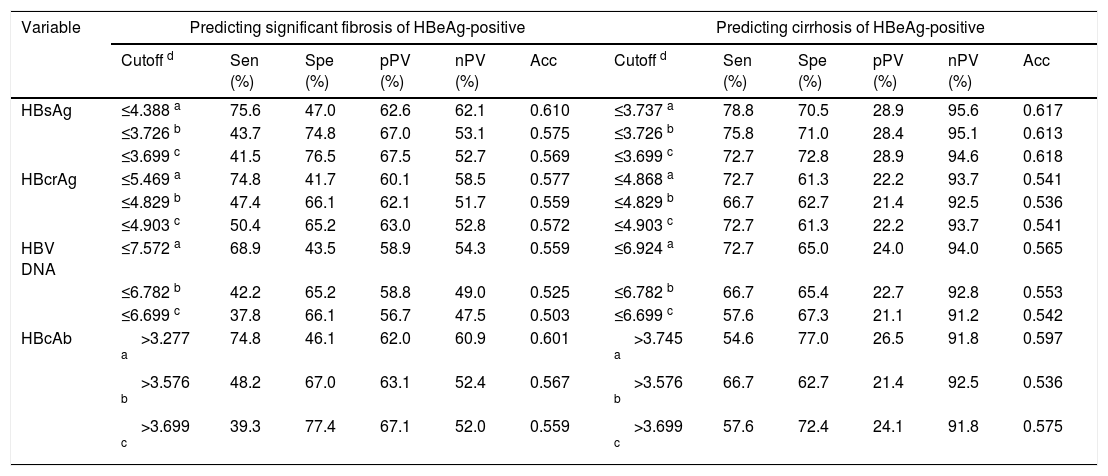

Performance of HBV markers in predicting significant fibrosis and cirrhosisWith reference to the Youden's index, an optimal cutoff was determined. According to the minimum difference in specificity of predicting significant fibrosis and sensitivity of predicting cirrhosis at the same cutoff, a tradeoff cutoff was selected. Near the tradeoff cutoff, an appropriate practical cutoff was chosen, in which “appropriate” was defined as that the specificity of predicting significant fibrosis and the sensitivity of predicting cirrhosis were both as large as possible and the cutoffs were easy to remember. The cutoffs and corresponding diagnostic parameters in predicting significant fibrosis and cirrhosis are summarized in Table 4.

Cutoffs and corresponding diagnostic parameters of investigated HBV markers in predicting significant fibrosis and cirrhosis.

| Variable | Predicting significant fibrosis of HBeAg-positive | Predicting cirrhosis of HBeAg-positive | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cutoff d | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | pPV (%) | nPV (%) | Acc | Cutoff d | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | pPV (%) | nPV (%) | Acc | |

| HBsAg | ≤4.388 a | 75.6 | 47.0 | 62.6 | 62.1 | 0.610 | ≤3.737 a | 78.8 | 70.5 | 28.9 | 95.6 | 0.617 |

| ≤3.726 b | 43.7 | 74.8 | 67.0 | 53.1 | 0.575 | ≤3.726 b | 75.8 | 71.0 | 28.4 | 95.1 | 0.613 | |

| ≤3.699 c | 41.5 | 76.5 | 67.5 | 52.7 | 0.569 | ≤3.699 c | 72.7 | 72.8 | 28.9 | 94.6 | 0.618 | |

| HBcrAg | ≤5.469 a | 74.8 | 41.7 | 60.1 | 58.5 | 0.577 | ≤4.868 a | 72.7 | 61.3 | 22.2 | 93.7 | 0.541 |

| ≤4.829 b | 47.4 | 66.1 | 62.1 | 51.7 | 0.559 | ≤4.829 b | 66.7 | 62.7 | 21.4 | 92.5 | 0.536 | |

| ≤4.903 c | 50.4 | 65.2 | 63.0 | 52.8 | 0.572 | ≤4.903 c | 72.7 | 61.3 | 22.2 | 93.7 | 0.541 | |

| HBV DNA | ≤7.572 a | 68.9 | 43.5 | 58.9 | 54.3 | 0.559 | ≤6.924 a | 72.7 | 65.0 | 24.0 | 94.0 | 0.565 |

| ≤6.782 b | 42.2 | 65.2 | 58.8 | 49.0 | 0.525 | ≤6.782 b | 66.7 | 65.4 | 22.7 | 92.8 | 0.553 | |

| ≤6.699 c | 37.8 | 66.1 | 56.7 | 47.5 | 0.503 | ≤6.699 c | 57.6 | 67.3 | 21.1 | 91.2 | 0.542 | |

| HBcAb | >3.277 a | 74.8 | 46.1 | 62.0 | 60.9 | 0.601 | >3.745 a | 54.6 | 77.0 | 26.5 | 91.8 | 0.597 |

| >3.576 b | 48.2 | 67.0 | 63.1 | 52.4 | 0.567 | >3.576 b | 66.7 | 62.7 | 21.4 | 92.5 | 0.536 | |

| >3.699 c | 39.3 | 77.4 | 67.1 | 52.0 | 0.559 | >3.699 c | 57.6 | 72.4 | 24.1 | 91.8 | 0.575 | |

| Test variable | Predicting significant fibrosis of HBeAg-negative | Predicting cirrhosis of HBeAg-negative | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cutoff # | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | pPV (%) | nPV (%) | Acc | Cutoff # | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | pPV (%) | nPV (%) | Acc | |

| HBsAg | >2.836 a | 82.3 | 36.9 | 45.7 | 76.4 | 0.543 | >2.996 a | 87.5 | 37.6 | 17.4 | 95.2 | 0.415 |

| >3.293 b | 53.1 | 56.4 | 44.0 | 65.1 | 0.543 | >3.293 b | 56.3 | 54.0 | 15.5 | 89.1 | 0.458 | |

| >3.301 c | 52.1 | 57.1 | 43.9 | 64.9 | 0.542 | >3.301 c | 56.3 | 54.9 | 15.8 | 89.3 | 0.463 | |

| HBcrAg | >1.161 a | 76.0 | 71.8 | 63.5 | 82.3 | 0.729 | >1.713 a | 90.6 | 71.4 | 32.2 | 98.1 | 0.651 |

| >1.850 b | 59.4 | 84.6 | 71.2 | 76.4 | 0.725 | >1.850 b | 84.4 | 75.1 | 33.7 | 97.0 | 0.664 | |

| >1.903 c | 57.3 | 85.9 | 72.4 | 75.7 | 0.722 | >1.903 c | 81.3 | 76.5 | 34.2 | 96.4 | 0.667 | |

| HBV DNA | >5.057 a | 50.0 | 88.6 | 73.8 | 73.3 | 0.699 | >4.587 a | 65.6 | 72.8 | 26.6 | 93.4 | 0.598 |

| >4.134 b | 61.5 | 71.1 | 57.8 | 74.1 | 0.661 | >4.134 b | 71.9 | 62.9 | 22.5 | 93.7 | 0.548 | |

| >4.000 c | 61.5 | 67.8 | 55.1 | 73.2 | 0.643 | >4.000 c | 71.9 | 60.6 | 21.5 | 93.5 | 0.533 | |

| HBcAb | >3.599 a | 83.3 | 30.2 | 43.5 | 73.8 | 0.500 | >3.916 a | 84.4 | 41.3 | 17.8 | 94.6 | 0.434 |

| >4.252 b | 47.9 | 56.4 | 41.4 | 62.7 | 0.519 | >4.252 b | 56.3 | 56.3 | 16.2 | 89.6 | 0.472 | |

| >4.301 c | 45.8 | 58.4 | 41.5 | 62.6 | 0.520 | >4.301 c | 53.1 | 58.2 | 16.0 | 89.2 | 0.475 | |

Sen, sensitivity; Spe, specificity; pPV, positive predictive value; nPV, negative predictive value; Acc, accuracy.

HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBcrAg, hepatitis B core-related antigen; HBcAb, antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen; HBV DNA, hepatitis B virus DNA.

Within the frameworks of HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients, respectively, we investigated comparatively the correlation of HBsAg, HBcrAg, HBV DNA and HBcAb of quantitative HBV markers with liver pathological grade and stage; and evaluated comparatively the performance of these HBV markers, and determined clinically valuable single tradeoff cutoffs and practical cutoffs of these HBV markers in not only affirming significant fibrosis but also screening cirrhosis.

Previous studies showed that, HBsAg, HBcrAg and HBV DNA are significantly negatively correlated with pathological grade and stage of HBeAg-positive patients, and significantly positively correlated with pathological grade and stage of HBeAg-negative patients;9–22 while HBcAb is significantly positively correlated with pathological grade and stage of both HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients.23–28 This study also displayed similar results. However, few studies have reported the differences in correlation strength between HBsAg, HBcrAg, HBV DNA and HBcAb with pathological grade and stage.9–28 This study showed that, the Spearman correlation coefficients of HBcAb with pathological grade and stage of HBeAg-positive and of HBeAg-negative patients are all close to those of HBsAg; nevertheless, of HBeAg-positive patients are respectively significantly greater than and close to those of HBcrAg and HBV DNA, and of HBeAg-negative patients are both significantly less than those of HBcrAg and HBV DNA. These findings suggested that, with hepatic aggravation of necro-inflammation and progression of fibrosis, of HBeAg-positive patients, the changes of HBcAb levels are in the opposite direction to those of HBsAg, HBcrAg and HBV DNA levels, and the pace of HBcAb increase is close to that of HBsAg decrease and faster than that of HBcrAg and HBV DNA decrease; almost the opposite, of HBeAg-negative patients, the changes of HBcAb levels are in the same direction as those of HBsAg, HBcrAg and of HBV DNA levels, and the pace of HBcAb increase is close to that of HBsAg increase and slower than that of HBcrAg and HBV DNA increase. These findings also provide further evidence for supporting the hypothesis that chronic HBV infection may evolve into four phases of immune exhaustion, immune activation, immune ignorance, and immune reactivation,22,34 in which circulating HBsAg is considered to be a key regulator of immune response against HBV.

Published studies demonstrated that, HBsAg and HBV DNA are respectively unquestionably and uncertainly valuable in predicting liver fibrosis levels of HBeAg-positive patients; conversely, HBsAg and HBV DNA are respectively questionably and certainly valuable in predicting liver fibrosis levels of HBeAg-negative patients.9–22 Preliminary investigations indicated that, HBcrAg and HBcAb are valuable in predicting liver fibrosis levels of both HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients.22,27,28 This study also showed similar results. However, few studies literatures have compared the differences in the validity between HBsAg, HBcrAg, HBV DNA and HBcAb in predicting liver fibrosis levels.9–22,27,28 ROC curve analyses of this study showed that, the AUCs of HBcrAg in predicting significant fibrosis and cirrhosis of HBeAg-positive patients are both close to those of HBsAg, and of HBeAg-negative patients are both significantly greater than those of HBV DNA; the AUCs of HBcAb in predicting significant fibrosis and cirrhosis of HBeAg-positive patients are both close to those of HBsAg and both close to those of HBcrAg, and of HBeAg-negative patients are both close to those of HBsAg and both significantly less than those of HBcrAg. Logistic regression analyses of this study displayed that, HBcAb and HBsAg are respectively the only marker for predicting significant fibrosis and cirrhosis of HBeAg-positive patients; HBcrAg is the only marker for predicting both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis of HBeAg-negative patients. These data suggested that, HBcrAg and HBcAb in predicting liver fibrosis levels of HBeAg-positive patients cannot be the dominant surrogate markers for HBsAg, and HBcrAg in predicting liver fibrosis levels of HBeAg-negative patients may be a potent surrogate marker for HBV DNA; while HBcAb and HBV DNA in predicting liver fibrosis levels of HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients can be a useful adjunctive marker, respectively.

Clear diagnosis of significant fibrosis and timely diagnosis of cirrhosis are crucial for effective management of chronic HBV infection.35–38 Therefore, compared with multiple optimal cutoffs for diagnosing different liver fibrosis levels, it is closer to clinical practice to select a single tradeoff cutoff to diagnose significant fibrosis with a lowest misdiagnosis rate and cirrhosis with a lowest missed rate. For the convenience of clinical application, we further chose a practical cutoff easy to remember by choosing one of 0, 2, 5 and 8, which is nearest to the integer reserved for the original number of the tradeoff cutoff expressed by scientific notation.

Based on the information of this study population, of HBeAg-positive patients, with standard of practical cutoff of HBsAg≤5, 000 IU/mL, the missed rate and misdiagnosis rate in predicting significant fibrosis are 58.5% and 23.5% respectively, and in predicting cirrhosis are 27.3% and 27.2% respectively; of HBeAg-negative patients, with reference to practical cutoff of HBcrAg>80 kU/mL, the missed rate and misdiagnosis rate in predicting significant fibrosis are 46.7% and 14.1% respectively, and in predicting cirrhosis are 18.7% and 23.5% respectively. These data further suggested that, HBsAg is a valuable but not satisfactory marker in predicting liver fibrosis levels of HBeAg-positive patients, which need combine HBcrAg or HBcAb improve its performance; while HBcrAg is a valuable and satisfactory marker in predicting liver fibrosis levels of HBeAg-negative patients.

This study had some limitations. Firstly, we did not study the relationships of HBcrAg and HBcAb with HBV genotypes, which might affect the measure results of HBcrAg and HBcAb. Secondly, we did not investigate the relationships of HBcrAg and HBcAb with HBV RNA, which is the updated HBV marker. Thirdly, as a clinical trial, we did not explore relationships of HBcrAg and HBcAb with intrahepatic HBV markers such as HBV DNA, HBV RNA and HBV covalently closed circular DNA. Fourthly, this is a cross-sectional study, and the argument is not stronger than a longitudinal study; however, performing a longitudinal follow-up is difficult, because many patients would receive antiviral therapy later.

In conclusion, with hepatic aggravation of necro-inflammation and progression of fibrosis, HBsAg, HBcrAg and HBV DNA of HBeAg-positive and of HBeAg-negative patients show respectively differential decrease and differential increase, while HBcAb of HBeAg-positive and of HBeAg-negative patients display both a gradual increase; the pace of HBcAb increase of HBeAg-positive patients is faster than that of HBcrAg and HBV DNA decrease, and of HBeAg-negative patients is slower than that of HBcrAg and HBV DNA increase. HBsAg is a valuable but not very good marker in predicting liver fibrosis levels of HBeAg-positive patients, while HBcrAg is a valuable and excellent very good marker in predicting liver fibrosis levels of HBeAg-negative patients.

Author contributionZhang-qing Zhang conceived and designed the study, and analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. Bi-sheng Shi, Wei Lu and Dan-ping Liu collated the data. Bi-sheng Shi and Dan-ping Liu performed the experiments. Bi-sheng Shi, Wei Lu, Dan Huang and Zhan-qing Zhang collaboratively collected the data. Yan-ling Feng performed pathological diagnoses. Zhan-qing Zhang, Bi-sheng Shi and Yan-ling Feng revised critically the manuscript.

Ethical standardsThis study was approved by the independent ethics committees of Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center of Fudan University (2013-K-008, 2016-S-046-02).

FundingThis work was supported by the “13th Five-year” National Science and Technology Major Project of China (2017ZX10203202), Shanghai Municipal Hospital of Joint Research Projects in Emerging Cutting-edge Technology (SHDC12016237).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The quantitative HBcrAg and HBc kits were kindly provided by Fujirebio Diagnostics, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan) and Innodx Biotech Co. Ltd. (Xiamen, China), respectively.