In December 2019, a novel coronavirus, called SARS-CoV-2, was isolated as a causative agent of a new form of pneumonia that has spread globally since then and was subsequently renamed COVID-19 by the World Health Organization.1 According to data from the Spanish Ministry of Health, as of 1 May 2020, the number of cases diagnosed by PCR in Spain surpassed 215,000 and the number of deaths stood at around 25,000, representing a mortality rate of 11.6%.2

Some patients experience cytokine release syndrome. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is the key molecule in this cytokine storm.3 Tocilizumab, a humanised recombinant monoclonal antibody, acts against the IL-6 receptor. For that reason, it has come to be used in patients with serious COVID-19 and elevated IL-6. Despite the apparent benefits reported, the possible adverse effects of this agent should be borne in mind. We report the case of a patient treated with tocilizumab for serious COVID-19 who presented signs and symptoms consistent with segmental ischaemic colitis.

A 59-year-old man was admitted to the intensive care unit for bilateral pneumonia due to SARS-CoV-2, complicated by moderate to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) requiring prolonged orotracheal intubation. Notable elements of his medical history were hypertension and ischaemic cardiomyopathy, for which he underwent revascularisation in February 2020 and was on dual antiplatelet therapy. After three days with boluses of methylprednisolone, the patient's condition worsened, with unfavourable laboratory and radiological test results, for which a single dose of 600mg of intravenous tocilizumab was prescribed. Ten days following administration of this drug, the patient started to have episodes of haematochezia which required transfusion of four units of packed red blood cells and one unit of platelets (two units of packed red blood cells approximately every 48−72h) due to the onset of multifactorial anaemia, as he reached haemoglobin levels of 7.2g/dl.

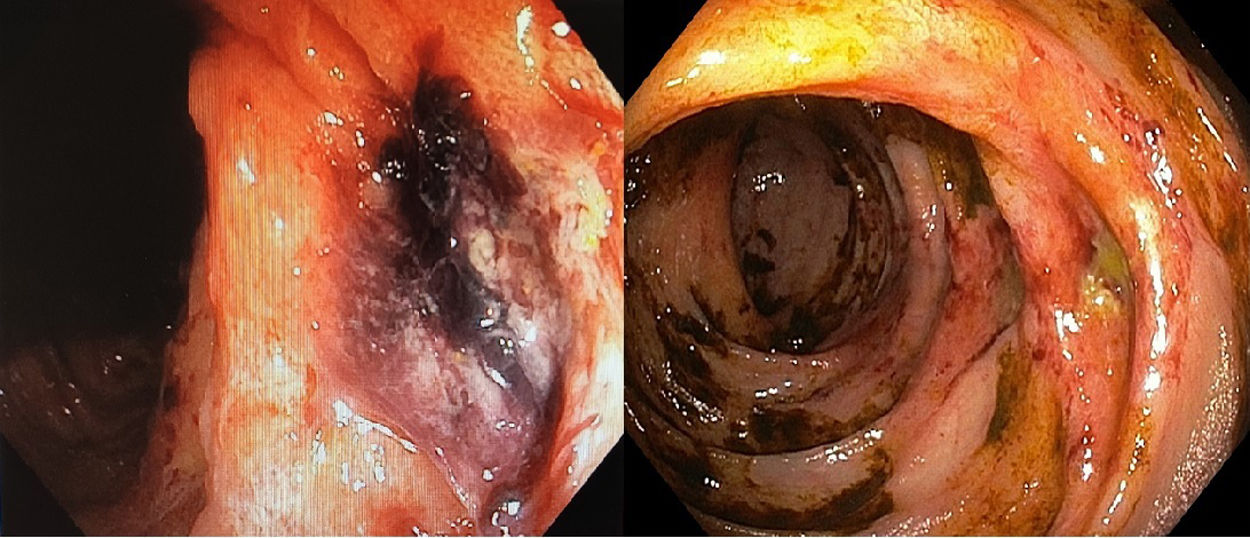

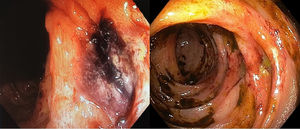

He underwent a colonoscopy 24h after the first episode of haematochezia. The procedure revealed digested blood debris (with no active bleeding) up to the hepatic flexure and signs in the mucosa of ischaemic colitis with two ulcers and an adhered clot 55–65cm from the external anal margin (Fig. 1). This colonoscopy was complete, although ileoscopy was not performed. A gastroscopy showed several gastric ulcers measuring around a millimetre suggestive of acute gastric mucosa lesions with no blood debris and no signs of active bleeding. In view of the endoscopic findings and the patient’s context, he was put on digestive rest with parenteral nutrition and broad-spectrum empirical antibiotic therapy. Days later, given the persistence of the patient’s haematochezia, a computed tomography (CT) angiography of the abdomen was ordered. This ruled out active bleeding and artery occlusion. It also found no segmental thickening or signs of a poor prognosis in the colon wall. As of that day, the patient's antiplatelet therapy was suspended. Two weeks from the first episode, the bleeding from the patient's rectum had been self-limited, so a decision was made to perform another colonoscopy (Fig. 1). This test showed the same lesions, now fibrinated, and improvement of the mucosal impairment in the same colon segment that was reported in the first endoscopy and classified as segmental ischaemic colitis. The colonoscopies found no diverticula in the colon.

The most common form of intestinal ischaemia is ischaemic colitis. It typically presents with colicky pain, defecation urgency and rectal bleeding. Most patients have mild forms that resolve within a few days with the mucosa recovering in two to three weeks. However, in more serious cases, recovery from the lesions may take up to six months, even if the patient remains asymptomatic. In addition, it must not be forgotten that a possible complication is bowel perforation.4

The recent COVID-19 outbreak has been deemed a global health emergency. As of the time of writing, there is still no effective treatment or available vaccine. Tocilizumab is useful in selected cases.3 Some possible adverse effects of a gastrointestinal nature of this drug are gastric ulcers (<2%), diverticulitis and gastrointestinal perforation.5 In our case, the patient presented colonic ulcers with episodes of haematochezia resulting in anaemia, which lasted for two weeks and ultimately were self-limiting.

The Naranjo algorithm was applied to determine the probability of a causal relationship between tocilizumab administration and ischaemic colitis, with a result of four points. Given all this, the possibility of an association must be taken into account. There are other limitations, such as the absence of a histological diagnosis of said ulcers, the presence of prior vascular disease and the patient's exposure to other events promoting possible ischaemic colitis (sepsis, hypotension, systemic impairment that required intensive care, etc.).

At present, in Spain there are several studies for evaluating the effects of tocilizumab in critically ill patients. Future lines of research could lead to studying the possible relationship between tocilizumab and ischaemic colitis. Few studies have observed an increase in gastrointestinal perforation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who receive tocilizumab, although the mechanism by which such damage occurs is unknown. One hypothesis points to inhibition by IL-6 of vascular endothelial growth factor, which plays an important role in maintaining the integrity of the intestinal mucosa when it is damaged.

FundingThere were no sources of funding for this work.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Forneiro Pérez R, Dabán López P, Zurita Saavedra MS, Hernández García MD, Mirón Pozo B. Tocilizumab como posible causa de colitis isquémica. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:373–374.