Splenosis is the ectopic splenic tissue autotransplanted following splenectomy or splenic trauma.1 This tissue may give rise to a mass or masses located in the peritoneum or extraperitoneally, which may present a difficult differential diagnosis. Occasionally, splenosis may produce abdominal pain, obstruction, and gastrointestinal bleeding.1,2

A 55-year-old male attended the emergency room (ER) for a new episode of melena in July 2018. Previous medical history included a necrotizing pancreatitis in 2003 with a splenic vein thrombosis with collateral circulation as a sign of prehepatic portal hypertension (PPH). In 2007 spleen rupture occurred. Since then, the patient presented several episodes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB). They were thought to be secondary to this PPH because on endoscopy an enlarged mucosal fold on the gastric fundus was found to be the source of bleeding recurrently (findings were: adherent clot to this fold, or an stomach full of blood with no alternative source). Despite different approaches (cyanoacrylate, aethoxysklerol, or arterial embolization of an active leak depending on the left gastric artery), UGIB episodes continued.

This time, a new endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) revealed a 39mm rounded, homogeneous, hypoechoic mass adjacent to the gastric fundus, with perforating vessels. A technetium (Tc) 99m-labelled heat-denatured erythrocyte scintigraphy (HDES) detected an uptake area in the gastric fundus. All this information was consistent with a diagnosis of splenosis. Selective cyanoacrylate injection under EUS guidance with disappearance of doppler uptake of the perforating vessels was done. Nevertheless, rebleeding occurred, and surgery was planned: a partial gastrectomy of the fundus was performed. In macroscopic examination, over the external surface of the gastric wall multiple solid nodular brown-violet formations are found measuring between 3 and 32mm, corresponding in the microscopic examination to splenic tissue including white and red pulp.

After an eighteen-month follow up, no rebleeding has occurred, anaemia is solved and stable, no more transfusions or iron supplements are required, and the patient is back to an active live.

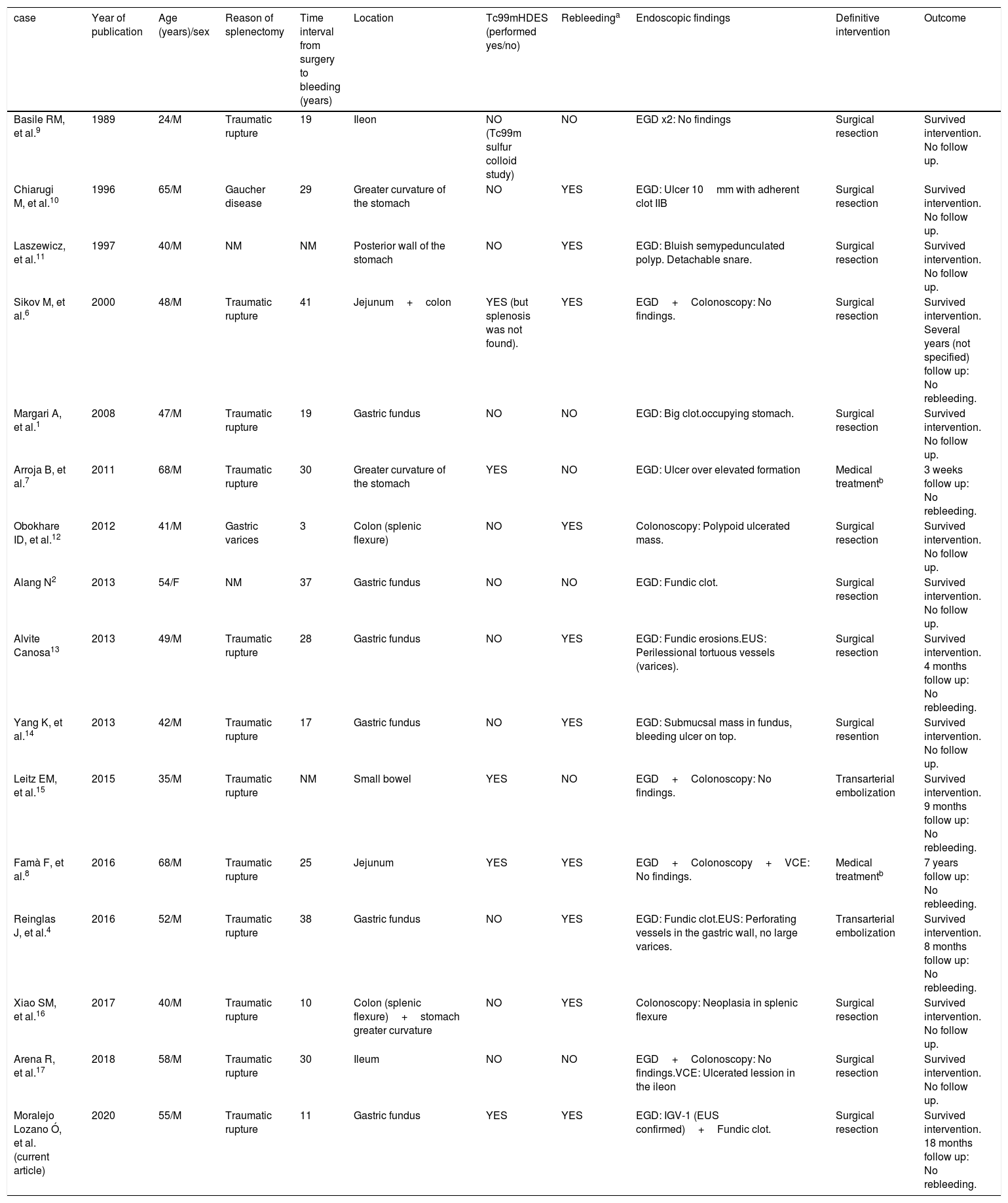

Previous published literature has been reviewed. We focused our interest on gastrointestinal bleeding due to splenosis. We conducted a search through PubMed using the MeSH terms “splenosis” and “bleeding” or “hemorrhage”, as well as through the references of the articles found. Language was limited to English. Fifteen previously cases were found, published between 1989 and 2019 (Table 1).

Summary of all cases reviewed.

| case | Year of publication | Age (years)/sex | Reason of splenectomy | Time interval from surgery to bleeding (years) | Location | Tc99mHDES (performed yes/no) | Rebleedinga | Endoscopic findings | Definitive intervention | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basile RM, et al.9 | 1989 | 24/M | Traumatic rupture | 19 | Ileon | NO (Tc99m sulfur colloid study) | NO | EGD x2: No findings | Surgical resection | Survived intervention. No follow up. |

| Chiarugi M, et al.10 | 1996 | 65/M | Gaucher disease | 29 | Greater curvature of the stomach | NO | YES | EGD: Ulcer 10mm with adherent clot IIB | Surgical resection | Survived intervention. No follow up. |

| Laszewicz, et al.11 | 1997 | 40/M | NM | NM | Posterior wall of the stomach | NO | YES | EGD: Bluish semypedunculated polyp. Detachable snare. | Surgical resection | Survived intervention. No follow up. |

| Sikov M, et al.6 | 2000 | 48/M | Traumatic rupture | 41 | Jejunum+colon | YES (but splenosis was not found). | YES | EGD+Colonoscopy: No findings. | Surgical resection | Survived intervention. Several years (not specified) follow up: No rebleeding. |

| Margari A, et al.1 | 2008 | 47/M | Traumatic rupture | 19 | Gastric fundus | NO | NO | EGD: Big clot.occupying stomach. | Surgical resection | Survived intervention. No follow up. |

| Arroja B, et al.7 | 2011 | 68/M | Traumatic rupture | 30 | Greater curvature of the stomach | YES | NO | EGD: Ulcer over elevated formation | Medical treatmentb | 3 weeks follow up: No rebleeding. |

| Obokhare ID, et al.12 | 2012 | 41/M | Gastric varices | 3 | Colon (splenic flexure) | NO | YES | Colonoscopy: Polypoid ulcerated mass. | Surgical resection | Survived intervention. No follow up. |

| Alang N2 | 2013 | 54/F | NM | 37 | Gastric fundus | NO | NO | EGD: Fundic clot. | Surgical resection | Survived intervention. No follow up. |

| Alvite Canosa13 | 2013 | 49/M | Traumatic rupture | 28 | Gastric fundus | NO | YES | EGD: Fundic erosions.EUS: Perilessional tortuous vessels (varices). | Surgical resection | Survived intervention. 4 months follow up: No rebleeding. |

| Yang K, et al.14 | 2013 | 42/M | Traumatic rupture | 17 | Gastric fundus | NO | YES | EGD: Submucsal mass in fundus, bleeding ulcer on top. | Surgical resention | Survived intervention. No follow up. |

| Leitz EM, et al.15 | 2015 | 35/M | Traumatic rupture | NM | Small bowel | YES | NO | EGD+Colonoscopy: No findings. | Transarterial embolization | Survived intervention. 9 months follow up: No rebleeding. |

| Famà F, et al.8 | 2016 | 68/M | Traumatic rupture | 25 | Jejunum | YES | YES | EGD+Colonoscopy+VCE: No findings. | Medical treatmentb | 7 years follow up: No rebleeding. |

| Reinglas J, et al.4 | 2016 | 52/M | Traumatic rupture | 38 | Gastric fundus | NO | YES | EGD: Fundic clot.EUS: Perforating vessels in the gastric wall, no large varices. | Transarterial embolization | Survived intervention. 8 months follow up: No rebleeding. |

| Xiao SM, et al.16 | 2017 | 40/M | Traumatic rupture | 10 | Colon (splenic flexure)+stomach greater curvature | NO | YES | Colonoscopy: Neoplasia in splenic flexure | Surgical resection | Survived intervention. No follow up. |

| Arena R, et al.17 | 2018 | 58/M | Traumatic rupture | 30 | Ileum | NO | NO | EGD+Colonoscopy: No findings.VCE: Ulcerated lession in the ileon | Surgical resection | Survived intervention. No follow up. |

| Moralejo Lozano Ó, et al. (current article) | 2020 | 55/M | Traumatic rupture | 11 | Gastric fundus | YES | YES | EGD: IGV-1 (EUS confirmed)+Fundic clot. | Surgical resection | Survived intervention. 18 months follow up: No rebleeding. |

EGD: Esophagogastroduodenoscopy, EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound, F: Female, IGV-1: Isolated gastric varices type 1, M: Male, NM: Not mentioned, Tc-99M HDES: Technetium (Tc) 99m-labelled heat-denatured erythrocyte scintigraphy, VCE: Videocapsule endoscopy.

Age ranged from 24 to 68 years (mean: 49.13 years; median: 48.50 years), mostly male (93.75%). Spleen rupture (75%) was the main reason for splenectomy. The interval time from splenectomy to diagnosis ranged from 3 to 41 years (mean: 24.07 years; median: 26.50 years). Most frequent location was the stomach (62.50%), followed by small intestine (31.25%) and colon (18.75%). This data contrast with the reported most frequent location of abdominal splenosis which are greater omemtum and serosal surface of small intestine.3 Recurrence of bleeding during hospital admission was common (62.50%).

Diagnosing splenosis can be challenging. Several imaging methods can be helpful such as abdominal ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), or standard magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) but a lack of specificity is present. Ferumoxide-enhaced MRI, Tc-99m sulphur colloid scintigraphy,3,4 or single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)5 have been described. However, technetium (Tc) 99m-labelled HDES is generally accepted as the most sensitive and specific test.3 It is to be noted that just in 37.50% of the cases HDES was performed, with the splenosis often being diagnosed intraoperatively. This could relate to a low grade of suspicion; but also, the clinical situation of the patient often required urgent surgery.

Definitive treatment for most cases was surgical resection (75%). However, conservative approach (12.50%) and arteriography (31.25%) have also been described. Arteriography was used in 5 cases, not detecting the bleeding source in 2 of them. When embolization was performed (3 cases), it was definitive just in two of them. In 56.25% of the cases no follow-up was reported. In those with informed follow-up, it was generally short, with only three cases (including ours) overcoming one or more years.6,8

As a conclusion, gastrointestinal bleeding due to splenosis occurs more commonly many years after splenectomy, mostly in males, with the gastric fundus as the most common location. It is frequently recurrent, and surgical resection is often required, but other approaches such as transarterial embolization4,15 or conservative treatment7,8 have also been reported.

FundingThe present investigation has not received specific aid from agencies from the public sector, commercial sector or non-profit entities.