El Monte Marino Alijos se localiza en el Océano Pacífico nororiental a unos 300km de la Península de Baja California. La edad y el análisis geoquímico de las rocas volcánicas que coronan este gran monte marino indican magmatismo reciente, que ha resultado de un proceso de diferenciación magmática a partir de magma basáltico medianamente alcalino. El Monte Marino Alijos está situado hacia el borde oriental de un mínimo de ondulación geoidal, de gran longitud de onda, que alcanza -47m con respecto al elipsoide del WGS84, y que se extiende sobre el Océano Pacífico nororiental. Restando de la ondulación geoidal su componente de gran longitud de onda y la ondulación debida a la topografía del monte marino, persiste una anomalía de ondulación negativa que indica un déficit de masa a profundidad. La inversión lineal de ésta anomalía de ondulación sugiere una región caracterizada por un contraste en densidad negativo, localizado por debajo del monte marino a profundidad entre 9 y 13km.

La edad y composición química del monte marino y el déficit de masa inferido, sugieren que existe magma atrapado entre la corteza oceánica y el manto superior, que explica la actividad magmática en tiempos recientes.

Escollos Alijos is a large seamount located in the NE Pacific Ocean about 300km off the Baja California Peninsula. Geochronology and geochemical analysis of volcanic rocks capping the seamount indicate recent magmatism that resulted from extensive differentiation of a mildly alkalic basalt parent magma.

Escollos Alijos is located towards the eastern edge of a long-wavelength geoid undulation minimum, of up to -47m with respect of the WGS84 ellipsoid, which extends over the northeastern Pacific Ocean. Subtracting from the geoid undulation its long-wavelength component and the undulation due to the seamount topography itself, a negative undulation anomaly persists that indicates a mass deficit at depth. Linear inversion of the undulation anomaly yields a region characterized by a negative density contrast, localized under the seamount at a depth between 9 and 13km.

The age and chemical composition of Escollos Alijos, and the inferred mass deficit suggest magma trapped between the oceanic crust and the uppermost mantle, which explains the magmatic activity in recent times.

The Escollos Alijos seamount is located at 24º 50’N latitude and 115º 34’W longitude, about 300km off the western continental margin of the Baja California peninsula (Figure 1). The bathymetry shows that the seamount is a compound of two flat-topped edifices, about 60km by 40km long at its base, and it sits on the seafloor at a depth of~4000m. On the sea surface Escollos Alijos consists of three craggy pinnacles, which rise to a maximum of 30m above sea level over an area of about 1000m2.

Study area showing bathymetry and topography at a contour interval of 1000m. Tectonic features of the Pacific Plate off Baja California adapted from Lonsdale (1991). The dashed lines represent fracture zones: Shirley (SFZ), Popcorn (PFZ) and Alijos (AFZ). Solid triangles indicate the fossil Cedros subduction zone. Remnants of Farallon plate: Guadalupe (GP) and Magdalena (MP) micro plates. Circles show DSDP holes 470 and 472. G-I is Guadalupe Island and A-S is Alijos seamount.

Davis et al. (1995) describe these rocks as europium-deficient trachyte that evolved by differentiation from a mildly alkalic parent basalt, and has laser fusion 40Ar/39Ar age of 270±16ka. These authors point out that the chemical composition of the volcanic rocks from Escollos Alijos is similar to that of Guadalupe Island (Figure 1). Batiza (1977) describes Guadalupe Island as an alkalic basalt seamount formed on a NS oriented spreading center with K-Ar age of 7.0±2.0 Ma. Later, Batiza et al. (1979) reported 40Ar/39Ar ages of 5.4±0.8 Ma and 3.7±0.4 Ma, as well as some volcanic rocks that were too young to be dated.

Marine magnetic anomalies (Lonsdale, 1991, Figure 9) suggest that Escollos Alijos sits on a 16-17 Ma old sea floor (Chron 5C), at about 200km from the Pacific–Farallon Ridge (Figure 1) that stopped spreading in mid-Miocene time, about 12 Ma ago, while Guadalupe and Magdalena plates stopped subducting. Escollos Alijos is elongated in the EW direction, parallel to a fracture zone (Figure 1) inferred by Lonsdale (1991) from marine magnetic anomalies. From the trachyte composition of rocks capping Escollos Alijos, and from magmatic activity in recent times, we may expect low-density magma in a localized magmatic chamber at depth, where differentiation takes place.

Except for work reported by Davis et al. (1995) and sparse marine gravity and magnetic data along ship tracks, Escollos Alijos Seamount and its surroundings remain unexplored. However, a homogeneous coverage of geoid undulations and free-air gravity anomalies from satellite altimetry with a spatial resolution of 1 arc minute, are available.

The geoid undulation from the Earth Gravitational Model 2008 (EGM2008) (Pavlis et al., 2012) over the northeastern Pacific Ocean (Figure 2) is characterized by a long-wavelength elliptically shaped -47m minimum referred to the World Geodetic System (WGS84) ellipsoid. The geoid undulation highlights several fracture zones, roughly oriented in an E-W direction, plus many seamounts.

Geoid undulation from the Earth Gravity Model 2008 (EGM2008) over the northeastern Pacific Ocean, exposing seamounts, oceanic islands, and fracture zones. The undulation associated to these physiographic features is within a long-wavelength undulation-minimum, with elliptical signature, that reaches about -47m with respect of the WGS84 ellipsoid.

Geoid undulations are due to density anomalies, as the geoid is warped up above mass excesses and down above mass deficiencies. Long-wavelength geoid features, as shown in Figure 2, have been attributed to density variations from mantle convection (McKenzie, 1983). Several long linear features shown in Figure 2, such as the Mendocino and the Tehuantepec fracture zones, among others, disrupt this geoid minimum. Since seamounts may be associated with short-wavelength geoid undulations, where the geoid is warped up, in this work I use geoid undulation data from the EGM2008 to infer, from linear inverse modeling, the subsurface density structure of Escollos Alijos.

The residual geoid undulationIn order to extract the geoid signal due to Escollos Alijos, one must estimate and remove the long-wavelength elliptical geoid undulation, attributed to density variations deep in the mantle. A review of geophysical applications of satellite altimetry (Cazenave and Roger, 2001) describes a widely used approach to estimate long-wavelength geoid undulations from geopotential solutions developed in spherical harmonics, up to a low degree of expansion (Sandwell and Renkin, 1988; Hager and Richards, 1989; Hager and Clayton, 1989). Another approach consists of applying a 2-D low-pass filter to gridded geoid data (Cazenave et al., 1992, 1996).

To extract the geoid undulation due to Escollos Alijos, an estimate of the long-wavelength component of the geoid was found by fitting, in the least squares sense, a bilinear polynomial surface to the geoid undulation from the EGM2008, in the vicinity of Escollos Alijos. The bilinear surface (Figure 3) nearly follows the long-wavelength geoid undulation trend, and was assumed that this surface locally represents the long-wavelength geoid undulation. This surface was subtracted from the EGM2008 geoid undulation to obtain a residual geoid undulation (Nr). The geoid undulation, the bilinear polynomial surface, and the residual geoid undulation in the vicinity of Alijos Seamount are shown in Figure 4.

The geoid undulation in a TM projection, with central meridian at -116o W longitude and false East at 500000m. Contour lines in m with respect to the WGS84 ellipsoid. The colored zone, in the vicinity of Alijos seamount, is a bilinear surface that locally represents the long-wavelength geoid undulation.

Data processing sequence to obtain the undulation anomaly in the vicinity of Alijos seamount: (a) Geoid undulation, (b) bilinear surface that represents the long-wavelength geoid undulation, (c) residual geoid undulation. All contour lines are shown in m with respect of the WGS84 ellipsoid.

The residual undulation (Figure 4c) is an elliptical feature with amplitudes varying from -0.273 to 1.877m. In the following section a solution to Bruns equation is derived to calculate the undulation due to a prism of constant density. This solution will later be used to discern if the residual undulation may be explained by the seamount topography alone.

Undulation due to a prism of constant densityThe undulation N at the point P(x0, y0, z0) caused by a prism of density r bounded by the planes x=x1, x2; y=y1, y2; z=z1, z2, is found from solving Bruns equation

where g=9.81 [ms-2] is the normal gravity, G≈6.674 x 10-11 [m3kg-1s-2] is Newton’s gravitational constant, R=(X2+Y2+Z2)1/2; X=x−x0, Y=y−y0, and Z=z−z0. As dX=dx, dY=dy, dZ=dz, equation (1) may be written

The integral in (2) with respect to the Z variable was obtained from Gradshtein and Ryzhic (1980) with the following result:

By partial integration, the integration of equation (3) with respect to Z yields

Similarly, integrating equation (4) with respect to X finally yields the desired solution

As an example, the undulation caused by a prism of constant density computed using equation (5) is shown in Figure 5.

Undulation due to Escollos Alijos and the surrounding sea floorThe undulation due to Escollos Alijos and the surrounding sea floor was computed using an array of rectangular prisms, each of 1km by 1km in its horizontal dimensions, in a model that includes the seamount, the sedimentary Layer 1, and the basaltic Layer 2.

In this calculation, the top of Layer 1 (Figure 6a) was defined by the bathymetry from the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans, and its thickness from a global estimate of sedimentary thickness by NOAA (<www.ngdc.noaa.gov/mgg/sedthick/>). The top of Layer 2 is conformable to layer 1 and its bottom extends down to 4200m below sea level, just exceeding the maximum thickness of the sedimentary layer (138m).

Graphic description of the data processing sequence: from the geoid undulation to the undulation anomaly in the vicinity of Alijos seamount. All contour lines are labeled in m, but the bathymetry that is labeled in km. (a) Bathymetry (ellipsoidal height) and thickness of the sedimentary layer with contours every 10m. (b) Undulation caused by the sedimentary Layer 1, the basaltic Layer 2, and the seamount core down to the base-level depth at 4200m. (c) Undulation anomaly.

Densities were assumed from density-logs at sites 470 and 472 (Figure 1) from Leg 63 of the Deep Sea Drilling Project (Yates et al., 1970), where the stratigraphic column consists of a sequence of Neogene sediments overlying basaltic pillow lavas of MORB composition. At site 472 the density (1500kg/m3) and seismic P-wave velocity (1420m/s) are nearly uniform throughout the sedimentary section down to 162m depth, and the basaltic layer has a density of 2770kg/m3 and seismic P-wave velocity of 5490m/s. At site 470 the density (1470kg/m3) and seismic P-wave velocity (1500m/s) are also uniform throughout the sedimentary section down to 112m depth, and the average density and P-wave velocity of the basaltic layer are 2790kg/m3 and 5510m/s.

The undulation due to the sediments and the basaltic layer 2 was calculated using a density contrast with respect to the seawater density (1030kg/m3). The density contrast of sediments was set to 470kg/m3, and the density contrast of the basaltic layer 2 was set to 1750kg/m3. Escollos Alijos was modeled, assuming the average density of trachyte (2600kg/m3), with a density contrast of 1570kg/m3.

The undulation computed from forward modeling (Figure 6b) varies between 1.264m and 5.201m, and its subtraction from the residual undulation (Nr) yields the undulation anomaly (Na) shown in Figure 6c, with values that vary between -1.243m and -3.405m. The negative undulation anomaly indicates a mass deficit below 4200m depth below sea level.

Studies using the teleseismic receiver function inversion technique at oceanic islands (Rarotonga, Kiribati, Tahiti, and Hawaii) with recent or active surface volcanism have found that between the lower crust and uppermost mantle, an anomalously slow seismic velocity is present, which has been interpreted as due to magmatic underplating (Leahy and Park, 2005; Leahy et al. 2010). The negative undulation anomaly at Escollos Alijos may also indicate magmatic underplating, as explored in the following section.

Inverse modeling the undulation anomalyInverse modeling of an undulation anomaly may yield an infinite number of density models. As a preferred density model (or a set of models) is desired as an outcome from the inversion, this objective is achieved by applying some regularization or physically reasonably constraints in the inverse problem (Jackson, 1979, Tarantola 2005) to find a particular solution to a non-unique inverse problem.

The geometry for the inversion is a cuboid that consists of a rectangular array of prismatic bodies. These prisms are arranged in layers; each layer has constant thickness and is constituted by a regular array of prisms. Each prism has fixed horizontal dimensions, and within every prism the density contrast is constant.

The model parameters, i.e. the density contrasts of the prisms in the cuboid, are represented by a vector m of dimension P that corresponds to the number of prisms in the cuboid. Vectors d and do, of dimension Q that denotes the number of data, respectively represent the solution to the forward problem and the undulation anomaly. With this notation the solution to the forward problem may be expressed as

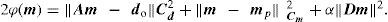

where each column of matrix A of dimension (Q, P) represents the solution of the forward problem for a prism of unit density. Assuming a priori Gaussian probability density functions for the data and model, with covariance matrices Cd and Cm, respectively, a solution to equation (6) may be found minimizing the following linear functional

The right hand side of equation (7) consist of a misfit term weighted by Cd=ε2I, where ε2 is the estimated data error variance, a model norm term weighted by Cm=σ2jI, where σj assigns a level of confidence in selected elements of the prior model mp, and a norm term that helps to impose smoothness in the solution, where α is a positive scalar that assigns importance to this constrain, and matrix D, of dimension (P, P) is a first- derivative operator that acts upon the model along the x, y, and z directions. Explicitly, the functional to be minimized is

Setting ∂ϕ(m)/ ∂m to zero, the solution of this inverse linear problem may be expressed as

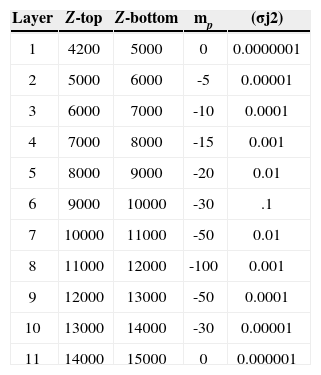

Results of the inverse modelingThe preferred model was found using a cuboid consisting of 11 layers of constant thickness, the layer 1 from 4.2 to 5km has a thickness of 800m, and from layer 2 to layer 11 the thickness was set to 1km, thus the cuboid model extends down to 15km below sea level. Each layer consist of a regular grid of 35 by 35 rectangular prisms, and each prism has horizontal dimensions of 4km by 4km. The value of α was set to 1000, and the prior model for each layer and their assumed variance are listed in Table 1. The overdetermined linear inverse problem was solved with 17161 undulation anomaly data (Q), distributed in a regular grid with nodes spaced appart 1km, assuming ε2=0.0001 as the data error variance.

11 layers of constant thickness, listed in m, for the cuboid model. For each layer, constituted by a regular array of 35 by 35 prisms, a prior (mp) density contrast (kg/m3) and variance (σj2) was assumed.

| Layer | Z-top | Z-bottom | mp | (σj2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4200 | 5000 | 0 | 0.0000001 |

| 2 | 5000 | 6000 | -5 | 0.00001 |

| 3 | 6000 | 7000 | -10 | 0.0001 |

| 4 | 7000 | 8000 | -15 | 0.001 |

| 5 | 8000 | 9000 | -20 | 0.01 |

| 6 | 9000 | 10000 | -30 | .1 |

| 7 | 10000 | 11000 | -50 | 0.01 |

| 8 | 11000 | 12000 | -100 | 0.001 |

| 9 | 12000 | 13000 | -50 | 0.0001 |

| 10 | 13000 | 14000 | -30 | 0.00001 |

| 11 | 14000 | 15000 | 0 | 0.000001 |

The observed and computed undulation anomalies and their misfit are shown in Figure 7. It is worth noting the smoothness of the computed undulation as compared with the undulation anomaly. The maximum misfit (Figure 7c) is located in the vicinity of Alijos seamount, where it varies between -10 and -20cm. In the region surrounding the seamount the misfit is less than±5cm. Figure 8 shows a 3D representation of the density contrast model, which varies between -293 to 15kg/ m3 and the minimum value is found in layer 7, between 10 to 11km depth, at the base of the oceanic crust, just under the seamount.

3D perspective views from the SW corner of the density contrast model from a cuboid constituted by 35x35x11 prisms. The density contrast values are assumed at nodes located at the centroid of the prisms. The top surface density contrast is shown in (a). From (b) to (f) are shown iso-surfaces of the following density contrasts: -250, -200, -150, -100, and -50(kg/m3); two sections that cross the model at the minimum density contrast show the interior of the model.

A negative undulation anomaly was found after subtracting from the EGM2008 geoid undulation an estimate of its long-wavelength undulation component and the undulation due to the seamount down to a base level at 4200m depth. The linear inverse modeling of the undulation anomaly yields a localized region with negative density contrast, situated at the base of the oceanic crust, which is interpreted as the possible source of the magma that sustains volcanic activity at Escollos Alijos in recent times. The mass deficit that produces the negative undulation anomaly, in addition to the young magmatic activity at Escollos Alijos and its chemical composition, supports the possibility of magmatic underplating at Escollos Alijos.

I gratefully acknowledge the review and comments by Alejandro Nava, Cinna Lomnitz, one anonymous reviewer, and the technical support by Victor Frías, Sergio Arregui and Julián Delgado. I acknowledge the work of the EGM2008 development team and the public release of geoid undulation data. This research was financed with fiscal funds provided to CICESE by Mexico’s Federal Government.