The current study investigated the effects of the physical activity-related psychological intervention via social network service (SNS) on physical activity and psychological constructs in inactive university students.

MethodThirty inactive university students participated in the 12-week intervention and received the physical activity-related psychological strategy via SNS. The physical activity levels, stages of physical activity, self-efficacy, pros, and cons were measured at the three time points (baseline, after 6 weeks, and after 12 weeks). Data analyses included frequency analysis, McNemar chi-square (χ2) test, and a repeated measures ANOVA were conducted.

ResultsResults indicated that the number of inactive university students gradually decreased across the three different time points, and that a total physical activity of inactive university students significantly increased over the 12-week intervention. In addition, pros and self-efficacy significantly increased but cons gradually decreased over the intervention.

ConclusionsThe current study suggests that the SNS-based physical activity-related psychological strategies have positive effects on promoting physical activity and its related psychological constructs for inactive university students.

Se investigaron los efectos de la intervención psicológica relacionada con la actividad física a través del servicio de red social (SRS) sobre la actividad física y los constructos psicológicos en estudiantes universitarios inactivos. Método: Treinta estudiantes universitarios inactivos participaron en la intervención de 12 semanas y recibieron la estrategia psicológica relacionada con la actividad física a través del SRS. Niveles de actividad física, etapas de la actividad física, autoeficacia, pros y contras se midieron en tres puntos temporales (línea base, después de 6 semanas y después de 12 semanas). Los análisis de datos incluyeron análisis de frecuencia, prueba de chi-cuadrado (χ2) de McNemar y un ANOVA de medidas repetidas.

ResultadosLos resultados indicaron que el número de estudiantes universitarios inactivos disminuyó gradualmente en los tres puntos de tiempo diferentes, y que la actividad física total de los estudiantes universitarios inactivos aumentó significativamente durante la intervención de 12 semanas. Además, los pros y la autoeficacia aumentaron significativamente, pero los contras disminuyeron gradualmente durante la intervención.

ConclusionesSe sugiere que las estrategias psicológicas relacionadas con la actividad física basadas en el SNS tienen efectos positivos en la promoción de la actividad física y sus constructos psicológicos relacionados para estudiantes universitarios inactivos.

It is reported that the university enrollment rate in South Korea is 75.7%, which means that the majority people in their 20 s, i.e., their early adulthood, are university students (Statistics Korea, 2019). Unlike elementary, middle, and high school years when most of daily schedules were generally organized by significant others, university years are more autonomous and an important transitional phase of one's life. This phase is critical in terms of building health habits because it is easy to gravitate toward behaviors that pose health risks, such as drinking and smoking (An et al., 2020). Moreover, since their lifestyles are not fully formed and the possibility of behavioral modifications is high compared to other age groups, university students undergo physical, emotional, and social changes to develop their health habits that are carried on to their adulthood (Park et al., 2018).

In this regard, it is also well recognized that physical activity habits during this period are a strong predictor for one's regular engagement in physical activity after graduation (Jackson & Howton, 2008). However, university students spend most of their time on sedentary rather than involving in regular physical activity to prepare for the extremely competitive job market (Korean Ministry of Culture & Physical Education, 2019). Moreover, a recent study indicate that university students spend most of their leisure time watching TV and Youtube, or playing smart phone and computer games, or using social media such as Facebook and Instagram, indicating a high level of physical inactivity compared to the time spent on physical activity (Sutherland et al., 2018). According to the national survey reported that 34.3% of Korean university students never exercised (men, 25%; women, 43%); while among 32.5% of students who engaged in physical activity did so fewer than three times a week (once a week, 15.8%; 2–3 times a month, 16.7%) (Korean Ministry of Health & Welfare, 2019). Like Korean statistics, according to World Health Organization (2021), many university students did not involve in regular physical activity in many countries. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2017) indicated that 56% of American university students showed lack of physical activity, including approximately 32% who never exercised.

Based on the awareness of the importance of regular physical activity and the lack of success of many approaches to promoting physical activity in daily life, theory-based intervention has been repeatedly encouraged (Kim & Kang, 2021). Additionally, if a physical activity intervention over relies on the behavioral processes of change, it likely will not appeal to those people who are not ready to take action. In this regard, a more promising approach might be to offer interventions that appeal to the vast majority of university students who are not ready to take action or to offer stage-matched interventions (An et al., 2020; Kim & Cardinal, 2009). Though certainly not without its critics (West, 2005), stage-matched physical activity interventions based on the transtheoretical model (TTM) have shown some promise for increasing people's physical activity behavior (Kim et al., 2006; Lee & Kim, 2015)

The TTM is a contemporary psychological paradigm that seeks to understand the adoption and maintenance of intentional health behavior and is also frequently used to classify physical activity correlates (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983). This model accounts for the dynamic nature of health behavior change including physical activity and recognizes that individuals often must make several attempts at behavior change before they are successful (Kim, 2004). The TTM comprises of five stages of change, known as the motivational aspects of change (i.e., precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance). Moreover, several psychological and behavioral constructs such as processes of change, self-efficacy, and decisional balance (i.e., pros and cons) have been shown to have significant relationships with the stages of change and are included in the model as other constructs (Kang & Kim, 2017).

For more than a decade, many studies across a wide range of populations and settings have shown the significant relationships between physical activity and the TTM constructs (Nigg et al., 2019; Shaver et al., 2019). Recently, the TTM-based strategies are being recognized as being effective interventions for not only promoting physical activity, but also in realizing positive changes on the psychological variables affecting physical activity (Kim & Kang, 2021; Lee & Kim, 2015). Moreover, it is well documented that the interventions based on the TTM can effectively deal with individuals’ various psychological needs related to physical activity (Kim & Cardinal, 2009). Recently, Kim and Kang (2021) applied a motivational reinforcement intervention combining physical activity and the TTM constructs for physical activity and its related psychological variables. The results indicated that obese women showed significant changes in physical activity level, as well as psychological variables such as improved exercise efficacy and decision balance after the intervention.

It is widely witnessed that the online communication relationships in contemporary society have rapidly changed due to the recent innovative developments of digital media and information and communication technology. Especially, portable devices, such as laptops and smartphones developed rapidly, and free wireless internet can be used anytime and anywhere. Thus, this is an era wherein information can be easily exchanged. Consequently, with the rapidly increasing wireless data usage, mobile-type wireless internet services are proliferating instead of website-based services (Cho, 2018). Particularly, Social Networking Service (SNS), which brings social relations to the online space where individuals are central players and points of connection, is used as a new communication tool combined with mobile technology (Baek & Lee, 2021).

Social media plays an important role as a tool that continuously strengthens online activities on platforms, such as Facebook, Instagram, NAVER (Korean social networking platform), or KAKAO Talk (Korean chatting application), facilitating communication among people. In other words, social media not only makes it possible to quickly and easily obtain information needed by various people, but also supports social networking. Communication through social media makes human life convenient and leads to rapid changes in human relationships (Keum, 2016). According to the 2019 Internet usage survey in Korea, social media usage rates were in the order of 20 s (87.1%), 30 s (77.2%), and 6–19 years old (54.5%). Most social media users over the age of 6 years (63.8%) used profile-based services, such as Facebook (66.3%), Instagram (49.9%), and Kakao talk (38.1%) (Korean Ministry of Science & ICT, 2019).

Recently, in the fields of preventive medicine and exercise psychology, it has been reported that the strategy for promoting physical activity using social media to promote physical activity increased participation rates in physical activity (Jingwen et al., 2016). Another study investigated and confirmed the effect of “fitspiration images or texts” posted on social media, such as Instagram, on psychological variables related to individual physical activity (Deighton-Smith & Bell, 2018). Moreover, Hongu et al. (2014) demonstrated the positive effects of using smartphone apps to promote health and physical activity among various age groups Best et al. (2016). developed a counselling program using smartphone apps and confirmed that this device is significant to increase participation in physical activity among wheelchair users. In Korea, not only was there a study that verified the effectiveness of developing walking and exercise programs based on a smartphone app (Choi & Chae, 2020; Ki & So, 2020), but also there is ongoing research to enable the effective application of these programs within clinical settings. Nevertheless, studies using social media based on integrating physical activity and the TTM constructs are lacking in Korea. The current study investigated the effects of the physical activity-related psychological intervention via SNS on physical activity and psychological constructs in inactive university students.

MethodParticipantsThe participants consisted of inactive university students enrolled at Seoul National University of Science and Technology located in the northern Seoul. In the initial stage of the study, participant recruitment consisted of posting an announcement about the study, including objectives and participant inclusion criteria, on the university's website and student bulletin board. University students who satisfied the following criteria were asked to voluntarily participate in the study: (1) falling under precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of physical activity based on the TTM, (2) not engaging in physical activity at the time of the study, and (3) no physical or mental illness and capable of communicating on their own. Through these processes, a total of 38 students met the three criteria and among them 30 (n = 30, mean age = 22.9 years, SD = 1.9) sent written consent form and participated in a 12-week intervention. The participants received a $50 prepaid coupon (authorized QR with Barcode) three times during the intervention. The coupon could be exchanged for various sporting goods such as socks, T-shirts, and sport pants. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University of Science and Technology.

InstrumentsAll measures were translated into Korean (Kim, 2002). The methodology of translation and validation for the measures outlined by Banville et al. (2000) was used. The full methodological process has been described in previous studies (Kang & Kim, 2017; Kim & Cardinal, 2009).

Stage of Physical Activity. The Stage of Change Scale for Exercise revised into Korean (Kim, 2002) was used to assess the physical activity stages. This measure has five stages that describe each individual's physical activity. The participants were asked to choose one of the five stages most consistent with their actual physical activity and its related intentions. In a pilot stage test-retest reliability was conducted as a measure of instrument stability, and obtained a reliability of 0.85, and the internal validity of the physical activity recall questionnaire was 0.81.

The Amount of Physical Activity. The Korean version of Leisure Time Physical Activity Questionnaire was used to assess habitual weekly physical activity behaviors (Kim et al., 2006). Participants reported how many times during a typical week they took part in strenuous (e.g., running, vigorous cycling), moderate (e.g., fast walking, easy swim), and mild (e.g., yoga, golf) physical activity for more than 15 min. The response score was calculated by multiplying each exercise intensity level to obtain the total metabolic equivalent (MET) value [MET score = (strenuous × 9) + (moderate × 5) + (mild × 3)]. The construct validity of the questionnaire was verified by the correlation with the accelerometer (Spearman's rho = .77), and Cronbach's α = .82 was reported for reliability (Kim et al., 2006).

Decisional balance. The Korean version of the Decision Balance Scale for Exercise was applied to evaluate perceived benefits and barriers to physical activity (Kim et al., 2006). The scale consists of the two sub-scales (pros and cons with five items each). Participants responded to each question according to their perceived level on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from not at all important (1) to extremely important (5). The test-retest reliability was performed to measure the questionnaire's stability, and the reliability was .91 for pros and .89 for cons.

Self-efficacy. The Korean version of the Exercise Self-Efficacy Scale was used to assess individual's confidence to exercise (Kim et al., 2006). The participants were asked to indicate how confident they were that they could perform exercise routines regularly (three or more times a week) under the different circumstances on a 5-point Likert scale from not confident at all (1) to very confident (5). The two-week test–retest reliability of the scale was .87.

ProcedureBefore implementing the intervention, the intervention procedures were explained to the participants, then the principal investigator shared a link of Naver Blog (Korean social networking platform) and an online chatting room on Kakao (Korean chatting application) with the participants. Participants were asked to complete the baseline questionnaires, which measure the stage and level of physical activity, self-efficacy, decision balance within 7 days via the online survey tool created on Naver Blog. After returning baseline questionnaire, the participants received personalized, self-instructional stage-matched materials via Naver Blog once a week over the 12-week intervention. In an attempt to increase response rates, a pre-notification alert was sent via Kakao chatting room to the study participants notifying them that the second questionnaire would be forthcoming. Moreover, in order to confirm participation, the participants were required to leave a comment on the group chatting room after reading the intervention messages. After receipt of this questionnaire, participants were again sent the appropriate intervention materials via Naver Blog. The same procedures were followed at the end of 12 weeks.

InterventionThe current intervention applied the behavior change strategies developed on the basis of previous TTM studies (Kim & Cardinal, 2009: Kim & Kang, 2021). The intervention protocol was reviewed for content validity by an expert review and discussion panel comprised of three people. The expert group consisted of two exercise psychologists with knowledge of TTM and one health professional with knowledge about physical activity. The experts reviewed the following components of the stage-matched materials: (a) intervention goals and objectives, (b) recommended behavior change strategies, and (c) physical activity examples. The intervention materials were based on the study participants’ current stage of change classification (i.e., precomplation, contemplation, and preparation) and they were accompanied by a short stage-matched cover letter. The intervention was designed to improve physical activity and bring about positive changes in psychological constructs associated with physical activity in inactive university students. This physical activity stage-matched strategy comprises of the most appropriate motivational cognitive and behavioral modification techniques for each of inactive and irregular stages Table 1.

The topics and techniques of the physical activity-related psychological strategy.

| Week | Topic | Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| 1–2 |

|

|

| 3–4 |

|

|

| 5–6 |

|

|

| 7–9 |

|

|

| 10–11 |

|

|

| 12 |

|

|

A McNemar chi-square (χ2) test was carried out to investigate the difference in the distribution of the physical activity stage over 12 weeks. A repeated measures ANOVA was performed to investigate changes in the levels of physical activity and psychological constructs (i.e., self-efficacy, pros, and cons over 12 weeks. Post hoc Bonferroni-corrected tests were used to identify significant differences between each of the three time points. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Win 26.0.

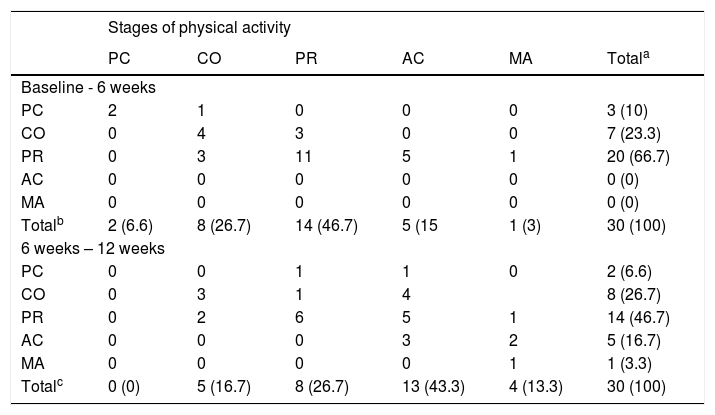

ResultsChanges in the stage of physical activityTable 1 shows the stage distribution of the study participants over the 12-week intervention. Overall, a majority of the study participants are preparation (66.7%) and followed by contemplaton (23.3%) and precontempltion (10%) at baseline. The number of inactive participants gradually decreased across the three different time points (precomplation: 6.6% at 6 weeks, 0% at 12 weeks; comtemplation: 16.7% at 12 weeks; preparation: 46.7% at 6 weeks, 26.7% at 12 weeks). A McNemar χ2 test was carried out to examine the differences in the stage transition in physical activity over the intervention and indicated significant differences between the three time points (χ2 = 14.24, df = 4, p = .01).

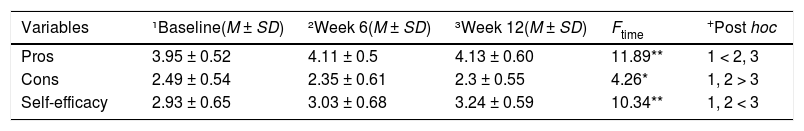

Effects of the physical activity-related psychological interventionTable 3 and 4 illustrate the results of the repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc contrasts for physical activity (i.e., METs) and its related psychological variables (i.e., self-efficacy, pros, and cons) across the three different time points. Results indicated that the total physical activity of inactive university students consistently increased across the 12-week intervention, and these changes were significant (F = 5.34, p < .01). In particular, mild physical activity (F = 5.41, p < .01) and moderate physical activity (F = 4.77, p < .01) were substantially increased across all the three different time points. Moreover, Table 4 shows psychological constructs were significantly changed over the 12-week intervention. In specific, inactive university students’ pros (F = 11.89, p < .001) and self-efficacy (F = 10.34, p < .001) significantly increased and their cons (F = 4.26, p < .05) significantly decreased over the intervention.

DiscussionThis study aimed at investigating the effect of the physical activity-related psychological intervention delivered by SNS over 12 weeks on changes in physical activity and psychological constructs among inactive university students.

The current study indicated that the stages of physical activity of inactive university students were significantly changed after the intervention, and this was supported by previous findings (Valle et al., 2015). In specific, the study participants consisted of inactive university students in the precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages based on the TTM. However, after the 12-week intervention 46.6% of the participants reported being in the action and maintenance stage.

Accompanying the positive changes in the physical activity stages, the participants also showed increases in their total physical activity levels across the intervention. Interestingly, there were significant change in the levels of mild and moderate physical activity, whereas strenuous physical activity was not significantly changed over the intervention. It is plausible to explain that providing the SNS-based physical activity messages is an effective strategy to positively change in physical activity (Parrott et al., 2008; Torniainen-Holm et al., 2016). In addition, it might be a possible reason to be considered that the inactive university students in this study might be happy and satisfied with mild-to-moderate intensity of physical activity or they might be preferred these intensities of physical activity with less physical burden because the study participants did not exercise at all or irregularly exercised. However, such interpretation needs to be considered with caution, because this finding has been obtained from only Korean inactive university students.

The current study indicated that pros and self-efficacy significantly increased during the intervention, with decreases in cons, and these findings are supported by previous studies (Lee & Kim, 2015; Kang & Kim, 2017). It is broadly documented that self-efficacy and decisional balance (i.e., pros and cons) are an important psychological determinant of physical activity in various cross-sectional studies (Kang & Kim, 2017). Especially, self-efficacy and pros are essential to strengthen individual's confidence and perceived benefits for physical activity adherence (Suton et al., 2013). Therefore, based on such cross-sectional findings it is clear that the intervention aiming at improving the level of physical activity should take an approach that focuses on positively changing self-efficacy and pros in a longitudinal viewpoint.

Considering the lack of research on psychological strategies using social media in behavioral medicine and health psychology, the current study indicates that the SNS-based intervention modality is a significant method to promote physical activity and positively change psychological constructs related to physical activity. Some studies have carried out to identify the effect of online physical activity interventions, yet limited evidence exists (Edney et al., 2017). Kang and Lee (2017) applied a smartphone app-based physical activity program (SPARK: Sport, Play and Active, Recreation for Kids) to the physical education class of junior high school and reported that this intervention played a significant role to improve physical activity participation and its related competence and enjoyment. More recently, Kwan et al. (2020) conducted systematic review and meta-analysis to identify the effect of e-health interventions on promoting physical activity. This study concluded that e-health interventions are effective at increasing the time spent on physical activity, energy expenditure in physical activity, and the number of walking steps. From these findings, it might be urgently needed to develop the SNS-based untact strategies and widely disseminate them to improve physical activity participation, considering that the Coronavirus-19 situation will be prolonged and this could be a major cause of sedentariness and physical inactivity.

There are a number of limitations should be considered. First, the study applied a quasi-experimental one group design employing a pretest-posttest. Without having a control group, it is impossible to know whether the changes observed were due exclusively to the intervention or whether there were other factors that contributed to the observed changes (e.g., attention, history, maturation). Second, the study participants may have spent time reading other physical activity-related posts outside of the study, which we were unable to objectively assess and account for in analyses. Third, given the relatively small and homogeneous sample from one university, the representativeness of the sample is not guaranteed. However, the objectives of this study are not descriptive, but seek to measure the changes of physical activity, self-efficacy and decisional balance in inactive college students. To this aim, longitudinal data was corrected to analyze those variables and provide concrete evidence of the intervention to meet this challenge efficiently and effectively (Cecchini et al., 2021). Fourth, the measures applied in this study underwent a rigorous and systematic translation and validation process. However, they relied on self-report, which may have added bias on the basis of item interpretation, recall, and social desirability, etc. Therefore, especially, using accelerometers is highly required to objectively measure physical activity (Cecchini et al., 2021).

Nevertheless, the current study is the significant trial to employ the intervention being delivered using a currently prevalent SNS-based modality based on the TTM as an organizing framework in inactive university students. Especially, as the medium of intervention was electronic (i.e., SNS), this can be recognized a rather novel and less studied intervention modality with the physical activity domain. The current study confirmed that the physical activity-related psychological intervention delivered by SNS was feasible for changing physical activity and its related psychological constructs. Therefore, further research should continue to investigate new ways to capitalize on the SNS features and functionalities that facilitate physical activity engagement and its longer-term adherence, and positively change psychological attributes related to physical activity.

FundingThis work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2020S1A5A2A03041894).

Stage distributions of physical activity over the 12 weeks.

| Stages of physical activity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC | CO | PR | AC | MA | Totala | |

| Baseline - 6 weeks | ||||||

| PC | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (10) |

| CO | 0 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 7 (23.3) |

| PR | 0 | 3 | 11 | 5 | 1 | 20 (66.7) |

| AC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| MA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| Totalb | 2 (6.6) | 8 (26.7) | 14 (46.7) | 5 (15 | 1 (3) | 30 (100) |

| 6 weeks – 12 weeks | ||||||

| PC | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 (6.6) |

| CO | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 8 (26.7) | |

| PR | 0 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 14 (46.7) |

| AC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 5 (16.7) |

| MA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (3.3) |

| Totalc | 0 (0) | 5 (16.7) | 8 (26.7) | 13 (43.3) | 4 (13.3) | 30 (100) |

Note. Parentheses are percent.

Changes in physical activity over the intervention.

| Variables | ¹Baseline(M ± SD) | ²Week 6(M ± SD) | ³Week 12(M ± SD) | Ftime | +Post hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total PA(METs) | 24.7 ± 18.75 | 32.53 ± 21.85 | 36.4 ± 19.38 | 5.34** | 1 < 2, 3 |

| Mild PA | 3.2 ± 2.49 | 4 ± 2.1 | 4.3 ± 2 | 5.41** | 1 < 2, 3 |

| Moderate PA | 1.9 ± 2.07 | 2.27 ± 1.89 | 3 ± 1.94 | 4.77** | 1, 2 < 3 |

| Strenuous PA | 0.93 ± 1.33 | 1.4 ± 1.47 | 1.3 ± 1.44 | 0.95 |

Note. METs: metabolic equivalents - equation: Total METs = (strenuous x 9) + (moderate x 5) + (mild x 3). **p < .01.

Changes in psychological variables over the intervention.

| Variables | ¹Baseline(M ± SD) | ²Week 6(M ± SD) | ³Week 12(M ± SD) | Ftime | +Post hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pros | 3.95 ± 0.52 | 4.11 ± 0.5 | 4.13 ± 0.60 | 11.89** | 1 < 2, 3 |

| Cons | 2.49 ± 0.54 | 2.35 ± 0.61 | 2.3 ± 0.55 | 4.26* | 1, 2 > 3 |

| Self-efficacy | 2.93 ± 0.65 | 3.03 ± 0.68 | 3.24 ± 0.59 | 10.34** | 1, 2 < 3 |

Note.+Mean differences for Bonferroni-corrected tests (p < .05); * p < .05, ** p < .01.