Emotional dysregulation (ED) is a transdiagnostic variable underlying various psychiatric disorders, including addictive behaviors (ABs). This meta-analysis examines the relationship between ED and ABs (alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, gambling, and gaming), and indicators of AB engagement (frequency, quantity/time of use, severity, and problems).

MethodSearches were conducted in PubMed, Scopus, WoS, and PsycINFO. Five separate meta-analysis were run using random-effects models. Moderators (age, sex, continental region, and sample type; community vs. clinical), and publication bias were evaluated.

ResultsA total of 189 studies (N = 78,733; 51.29 % women) were identified. ED was significantly related to all ABs. Problems and severity indicators exhibited the largest effects (r’s .118-.372, all p <.023). There were larger effect sizes for cannabis problems (r = .372), cannabis severity (r = .280), gaming severity (r = .280), gambling severity (r = .245), gambling problems (r = .131), alcohol problems (r = .237), alcohol severity (r = .204), and severity of nicotine dependence (r = .118). Lack of impulse control exhibited some of the largest effects in relation to ABs. Clinical samples of cannabis users vs. community-based exhibited larger magnitude of associations.

ConclusionsInterventions targeting ABs should address lack of strategies and impulsive behaviors as an emotion regulation strategy specifically, as it is a common risk factor for ABs.

Emotional dysregulation (ED) is a transdiagnostic variable underlying multiple mental health disorders in both adults and young populations, including depression, anxiety, and eating disorders (Aldao et al., 2010; Guerrini-Usubini et al., 2023; Sloan et al., 2017), but also addictive behaviors (ABs) (including both substance use disorders and behavioral addictions) (Stellern et al., 2023; Weiss et al., 2015; Weiss et al., 2022). There is also evidence supporting ED playing a role in alcohol-related problems (Fairholme et al., 2013; Weiss et al., 2018b), cocaine (Tull et al., 2016) and cannabis use (Lucke et al., 2021), and other related variables, such as craving (Ghorbani et al., 2019) and withdrawal (Rogers et al., 2019). ED is a predictor of Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) and gambling (Marchica et al., 2019), and a risk factor for binge drinking, especially in young men (Laghi et al., 2019).

There have been multiple attempts to define ED, but there is no agreement yet on the conceptual core of this construct (D’ Agostino et al., 2017). One of the most widely adopted definitions was provided by Gratz and Roemer (2008), who consider ED to be a multidimensional variable referring to difficulties in understanding emotions, lack of acceptance of emotions, the ability to engage in goal-directed behavior, and refraining from impulsive behaviors when experiencing negative emotions.

The association between ED and ABs appears to be reciprocal (Hessler & Katz, 2010; King et al., 2023). So far, various meta-analyses and systematic reviews have examined the relationship between ED and ABs. Lannoy et al. (2021) provided evidence of difficulties in emotional regulation (ER) in young people with hazardous drinking, although the findings were supported by one study and were generally inconsistent across others. Moreover, the studies they reviewed looked at adolescents, and no alcohol use patterns other than binge drinking were explored. Aldao et al. (2010) examined the effect of rumination, suppression, and avoidance on substance use (collapsing for all substances) in adults and adolescents. No other ED abilities or strategies (e.g., self-blaming, lack of emotional clarity) were explored in their review and it did not specifically look at the moderating effects of sex, age, or other sample characteristics. Similarly, Weiss et al. (2022) reported larger effect sizes for substance use in relation to ER abilities (e.g., impulse control difficulties) than strategies (e.g., expressive suppression). However, a notable limitation of this study is that they looked at specific categories of substance use (alcohol use only, drug use only, tobacco use only, use of multiple substances), and variables related to ABs were collapsed together, which seriously restricts the conclusions. In addition, they did not consider adolescent samples and behavioral addictions.

As regards to non-substance use ABs, a systematic review of studies with adolescents and adults by Velotti et al. (2021) showed that some ED strategies (e.g., non-acceptance of negative emotions, difficulties in maintaining goal-directed behaviors) were positively correlated with problem gambling. Age moderated the relationship between gambling disorder (GD), lack of clarity, and difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviors. In addition, both being older and being male moderated the effect of the non-acceptance of emotions on GD. Lastly, several literature reviews and meta-analyses have suggested a moderate relationship between IGD and some cognitive maladaptive behaviors (i.e., blaming others, emotional suppression, rumination) (Estupiñá et al., 2024; Ji et al., 2022; Marchica et al., 2019). However, the associations are too varied so far and comprehensive assessments of specific ED strategies have yet to be conducted.

Collectively, prior studies have focused on different ABs and none of them have examined ED across different substance use and non-substance use behaviors, considering different patterns of use. This is at odds with more recent conceptualizations of ED as a transdiagnostic process underlying the onset, development, and continuation of multiple health risk behaviours (Shadur and Lejuez, 2015; Sloan et al., 2017; Westphal et al., 2017). The fact that prior research has not examined the detail of relationships with ED by substance use and non-substance use indicators (e.g., frequency or severity) is a limitation, as that makes it more difficult to identify potentially relevant prevention and treatment targets in clinical and community samples.

People's ability to regulate emotions may be influenced by a variety of conditions, including culture, substance use, age, and sex. To date, there has been little examination of these variables as potential moderators of the relationship between ED and ABs. The existing evidence suggests stronger associations in samples of older people in relation to gambling severity (Velotti et al., 2021) and substance use more generally (Weiss et al., 2022). There is also some research suggesting cultural differences in ED indicating Asian people experience greater difficulties in ED, frequent use of suppression and rumination (Ford & Mauss, 2015; Su et al., 2015) and that clinical samples employ dysfunctional ED strategies (e.g., rumination, suppression) more frequently than community populations (Chen et al., 2020; D'Avanzato et al., 2013). Although ED relates to the severity of psychiatric disorders (Joorman & Stanton, 2016, Joseph et al., 2024; Oliva et al., 2023), whether this applies to substance use disorders and behavioral addictions has not been examined in close detail in a meta-analysis. Furthermore, men and women seem to differ in their difficulties with ER (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2012; Weiss et al., 2022). In this regard, there are different studies showing that women's greater tendency than men to engage in dysfunctional strategies is a significant mediator of their greater levels of psychopathology compared to men (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012). Unfortunately, most of the discussion of sex differences in ED has focused on depression and anxiety, and understanding whether ED plays any role in ABs in men and women is a priority. This is a gap in the literature that, once filled, is expected to help in the design of more effective interventions, especially considering that sex differences in patterns of AB engagement have been reported throughout the literature (Erol and Karpyak, 2015; Halladay et al., 2020; McHugh et al, 2018; Windle et al., 2020).

Against this background, this study consisted of five separate meta-analyses that sought to examine the role of ED in multiple ABs, including substance use (i.e., alcohol, tobacco, cannabis) and behavioral addictions (i.e., gambling and gaming). There were two specific aims: i) to examine the cross-sectional relationships between ED strategies and specific patterns of engagement in ABs (i.e., frequency of use, quantity/time of use, severity, and problems); and ii) to provide evidence on potential moderators (sex at birth, age, continent region, and clinical vs. community samples) in the relationships assessed. The methodological quality and publication bias of the reviewed studies were examined as well. It was hypothesized that: 1) significant relationships would emerge between ED and all ABs; 2) significant moderating effects would emerge by sex (higher effects for women vs. men), continental region (higher effects for Asian countries), and population type (higher for clinical vs. community samples), but not by age.

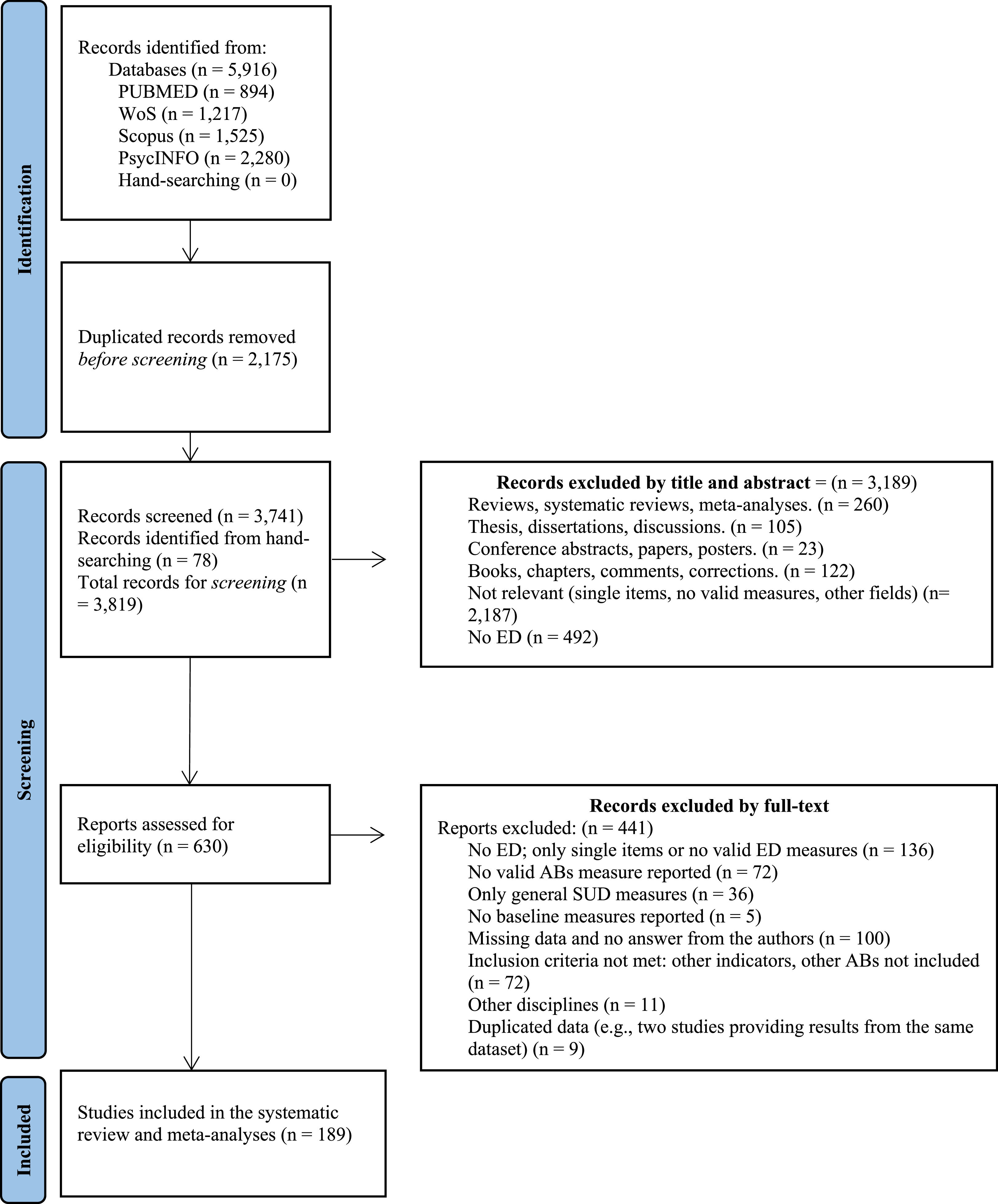

Materials and methodsLiterature search procedure and eligibility criteriaThis study followed the PRISMA statement (Page et al., 2021) and was pre-registered in PROSPERO (ID: CRD42021250237). It also conformed to both the Journal Article Reporting Standards (JARS) and Meta-Analysis Reporting Standards (MARS) (see Appelbaum et al., 2018). Literature searches were conducted up to July 2023 in the following databases: PsycINFO, PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus. As a supplemental approach, we conducted a manual search to identify additional primary studies as of the reference list of the studies retrieved in electronic databases. Specific MeSH terms were used in each of the databases (see supplementary Table A.1).

The primary inclusion criteria for this study pertained to peer-reviewed articles assessing the cross-sectional relationship between ED strategies and ABs. Whenever studies used measures of both ER and ED, only ED were considered for consistency with the aims of the study. To be included in the meta-analyses, potentially eligible studies had to: 1) use a validated measure of ED; and 2) provide a measure of at least frequency, quantity of use or time invested, problems, or severity of ABs (including alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, cocaine, heroin, opioids, methadone, stimulants, gambling, or gaming). Data not reported were requested from the corresponding authors. A total of 100 authors were contacted to provide data, and 19 (19 %) did so.

Data collection processTwo independent reviewers individually screened the full text of potentially eligible studies. For each study, we extracted the following variables: author(s), country, sample size, sex (% females), sample type (e.g., clinical or community), age, measure of AB (i.e., frequency, quantity/time of use, severity, and problems), substance use measure, co-occurrent behaviors, measure of emotional regulation, and effect size (i.e., zero order correlation) of the relationship between ABs and ED.

Meta-analytic approachThe software Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (v 4.0) was used. Meta-analyses were performed based on Pearson correlations using a random effects model. Cochran's Q and I2 were computed to characterize heterogeneity, with values ≤ 25 % suggesting low heterogeneity, values around 50 % signaling moderate heterogeneity and values ≥75 % indicating high heterogeneity across studies (Higgins et al., 2003).

To avoid heterogeneity across ABs, five separate meta-analyses were performed to examine the unique relationship between each AB (alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, gambling, and gaming) and ED (total score), and ED strategies. It is worth noting that the meta-analysis of the relationship between cocaine and ED (total score) could not be computed, due to insufficient available effect sizes (i.e., N = 1). In absence of an ED total score, whenever all subscales of ED questionnaires were available, a composite score was calculated for meta-analysis. As per prior recommendations (Corey et al., 1998), we used Fisher's z transformations and performed the analyses using this index. Then, we converted the summary values back to correlations for presentation. The Fisher's z essentially normalizes the sampling distribution and thus can be used to obtain an average correlation that is less affected by the skewness of the sampling distribution. Zero order correlations were the effect size metric selected to report results. Cohen's criteria for small (>0.20), moderate (>0.50) and large (>0.80) effect sizes were used to aid the interpretation of results (Cohen, 1988).

A set of Q-tests were conducted to examine differences in the relationship between ED (total score) and ABs by substance use or behavioral addiction indicator (i.e., frequency, quantity/time of use, severity, and problems), if available. Q tests were also conducted to examine differences in the relationship between ED and ABs by continental region [i.e., Europe (France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, Italy, Poland, Spain, Sweden, the UK), North America (Canada, the United States of America), Central and South America (Argentina, Ecuador, Mexico), Asia (China, Iran, Israel, Lebanon, South Korea, Turkey), Oceania (Australia)]. Meta-regressions, at a two-sided 95 % CI, looked at the potential mediating role of female sex and age. The moderating role of sample type (clinical vs. community) was also examined. Effect sizes in the relationship between ED and ABs were specifically conducted by sample type and are provided in the main body of the manuscript. Therefore, generalizability to clinical and non-clinical populations is ensured, given that we conducted subgroup analyses for both clinical and community samples by ABs specifically, and then performed Q-tests, (akin to t-tests for independent samples). We adopted common definitions of clinical and community samples as followed in popular and well-powered national surveillance studies, such as the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) (Blanco et al., 2008; Okuda et al., 2010). Clinical samples were defined as individuals with a current diagnosis of substance use disorder and/or receiving treatment for substance use or other psychiatric disorders. Community samples included participants recruited from the community that did not meet clinical diagnosis criteria and were not receiving treatment.

Methodological quality assessmentRisk of bias was assessed by two independent reviewers using an adapted 5-item version of the Joanna Briggs Institute [JBI] Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies (Desalu et al., 2019; Joanna Briggs Institute, 2020). The scale assesses the quality of studies based on eight items: (1) inclusion criteria; (2) study subjects and setting; (3) exposure measured in a valid and reliable way; (4) objective and standard criteria used for measurement of the condition; (5) confounding factors; (6) strategies to deal with confounding factors, (7) outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way and (8) appropriate statistical analysis. Items 5, 6, and 8 were not used in the methodological quality assessment to avoid methodological bias. Since our meta-analyses included only cross-sectional correlations, it would have been possible for a specific paper to be scored as poor quality just because it intended to provide exploratory assessments through zero order correlations, instead of a more robust analysis (e.g., partial correlation). The percentage of “yes” answers in the JBI was computed for each reviewed study, and interrater reliability assessment using Kappa values was also provided.

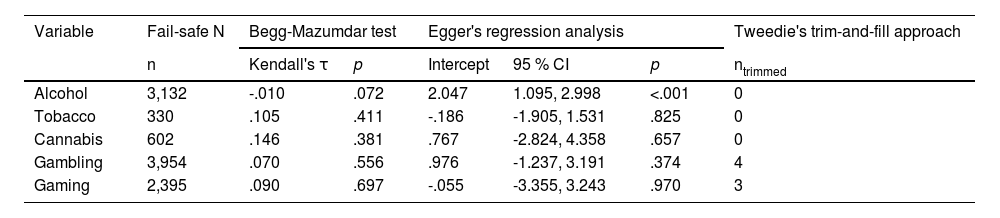

Publication bias in meta-analyses was examined using four indices: 1) Egger's test (Egger et al., 1997); 2) the Begg and Mazumdar rank (Begg and Mazumdar, 1994); 3) Duval and Tweedie's trim-and-fill (Duval and Tweedie, 2000); and 4) the leave-one-out ‘jack-knife’ sensitivity analysis (Sinharay, 2010).

ResultsA flow chart summarizing the literature search process is presented in Fig. 1. A total of 5,916 studies were initially identified through electronic databases, and 189 were finally retained in the meta-analyses.

Supplementary Table A.2 summarizes the study characteristics. Most of the studies (n = 129/189) focused on the relationship between ED and alcohol use. A total of 26/189 focused on tobacco, 15/189 on cannabis, 36/189 studies provided data on gambling, and 12/189 on gaming. For some ABs, there are more cases than studies, given that some studies reported on the relationship between a given ABs and ED (total score) and provided the correlation as well between ABs and specific ED dimensions. The total number of cases that were meta-analyzed can be seen in Table 1.

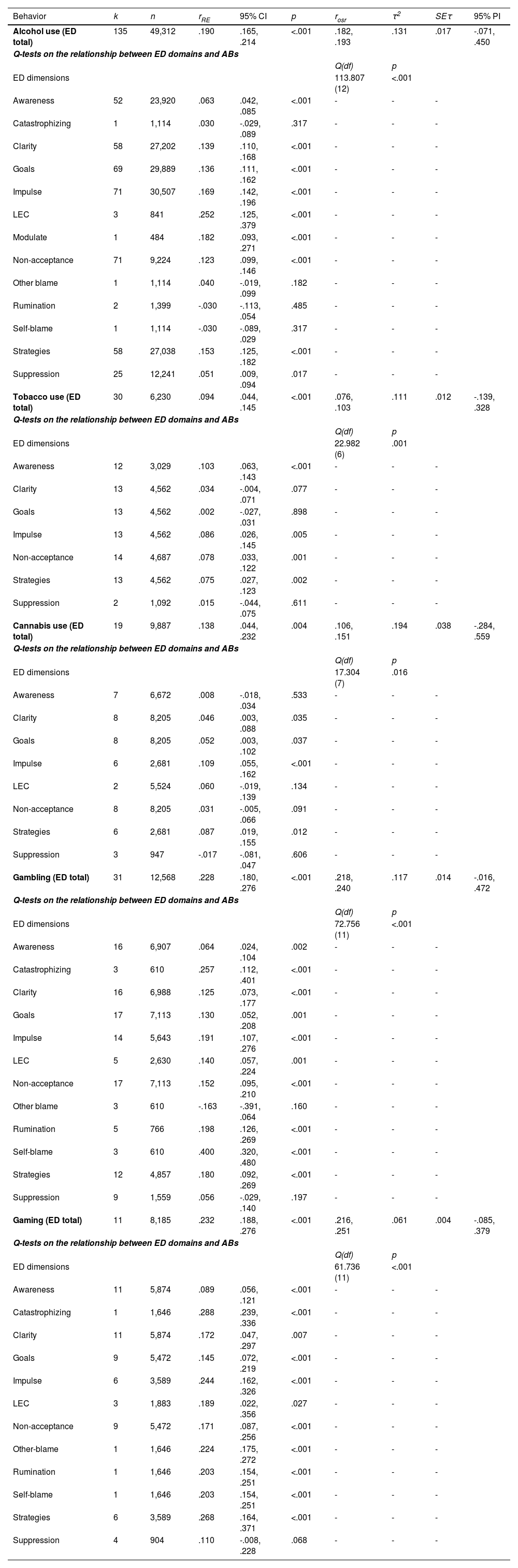

Omnibus effect sizes on the associations between addictive behaviors and emotional dysregulation (total scores)

Note. The table displays the five separate meta-analyses on the associations between each addictive behavior and emotional dysregulation (total scores). Below, it informs on the unique effect between each emotional dysregulation dimension and addictive behaviors and inter-group differences (see Q test and associated p value).

k = number of studies; n = sample size; rRE = correlation from the random effects model; 95 % CI = 95 % confidence interval; rosr = range of effect sizes from the Jackknife analysis; τ2 = Tau squared coefficient; SEτ = Tau squared standard error. ED = Emotion dysregulation; LEC = Lack of emotional control; 95 % PI = 95 % Prediction Interval.

The sample consisted of 78,733 participants (N range 21-3,707), 51.29 % female. Average age was 29.74 (SD = 7.62). Most of the studies were conducted in the US (112/189; 59.2 %), followed by Spain (16/189; 8.5 %), Italy (15/189; 7.9 %), Canada (9/189; 4.8 %), Australia (7/189; 3.7 %), France (4/189; 2.1 %), Iran (3/189; 1.6 %), UK (2/189; 1.1 %), Turkey (2/189; 1.1 %), Sweden (2/189; 1.1 %), South Korea (2/189; 1.1 %), Poland (2/189; 1.1 %), Ecuador (2/189; 1.1 %), China (2/189; 1.1 %), Norway (1/189; 0.5 %), Netherlands (1/189; 0.5 %), Mexico (1/189; 0.5 %), Lebano (1/189; 0.5 %), Israel (1/189; 0.5 %), Ireland (1/189; 0.5 %), Hungary (1/189; 0.5 %), Germany (1/189; 0.5 %), and Argentina (1/189; 0.5 %).

Of the reviewed studies, a total of 31.75 % (60/189) included people with co-occurrent ABs, 21.16 % (40/189) with post-traumatic stress disorder or trauma exposure, 16.93 % (32/189) with mood disorders, 11.64 % (22/189) with anxiety disorders, 4.76 % (9/189) with eating disorders, 3.17 % (6/189) with self-harm or suicidal ideation, 2.12 % (4/189) with psychotic disorders and neurodevelopmental disorders, and 1.59 % (3/189) with personality disorders. The remaining (6.88 %; 13/189) included community-based samples.

Measures of emotion dysregulation (ED)There were 149/189 (78.84 %) studies that used the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS-36), 7/189 used the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale-Positive (DERS-P) (3.70 %), 5/189 used the 28-item version of the DERS (2.65 %), 2/189 used the DERS-18 (1.06 %), 10/189 used the DERS-16 (5.29 %), 4/189 used the abbreviated version of the DERS (i.e., DERS-SF) (2.12 %), 1/189 used the M[modified]-DERS (0.53 %), 1/189 used the State Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (S-DERS) (0.53 %), 1/189 used the Mexican adaptation of the DERS (DERS-E) (0.53 %), and 1/189 used the Revised version of the DERS (DERS-R) (0.53 %). A total of 29/189 (15.34 %) of the studies used the “expressive suppression” subscale from the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ), 8/189 (4.23 %) of the studies used the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ), and 1/189 (0.53 %) used the 18-item version of the CERQ (i.e., CERQ-18). 2/189 (1.06 %) used the Rumination subscale of the Rumination Reflection Questionnaire (RRQ).

Measures of addictive behaviors (ABs)Measures of ABs comprised frequency (35/189; 18.52 %), quantity of use or time invested (31/189; 16.40 %), severity (158/189; 83.60 %), and problems (34/189; 17.99 %). Frequency, quantity, and time invested were self-reported and measures varied for the different ABs (e.g., drinking days during past week, tobacco use in the past month, or number of hours gamed per week). Studies focusing on gambling and gaming did not provide effect sizes for quantity.

Most studies included validated questionnaires to assess severity. The most common measure for evaluating hazardous alcohol use was the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; 83/102; 81.37 %). All measures of tobacco severity included the Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (FTCD; 13/13; 100 %). Cannabis use was measured with the Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST; 1/3; 33.33 %), the Cannabis Use Disorder-Clinician Severity Rating (CUD-CSR; 1/3; 33.33 %), and the Cannabis Abuse Screening Test (CAST; 1/3; 33.33 %). Gambling severity was mostly assessed with the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS; 17/31; 54.84 %), whereas the Game Addiction Scale (GAS; 3/7; 42.86 %) was the most used gaming measure.

Alcohol problems were most often evaluated by the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (YAACQ; 6/24; 25 %). No study examined this indicator for tobacco, and the Marijuana Problem Scale (MPS; 4/4; 100 %) was the only instrument used for cannabis problems. Gambling problems were assessed using the CAGE version of the Attentional Center for Drug-Addiction (MULTICAGE CAD4; 1/2; 50 %) and the short version of the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) (SPQ; 1/2; 50 %). Finally, four instruments were used to assess problems in gaming, the MULTICAGE CAD-4 (2/5; 40 %), the Questionnaire of Experiences Related to videogames (CERV; 1/5; 20 %), the Internet Addiction Test – WoW Version (IAT-WoW; 1/5; 20 %) and the Problem Video Game Playing Scale (PVP; 1/5; 20 %).

Meta-analysesTable 1 shows the random-effects meta-analyses of the relationships between ED (total score) and strategies by substance use and non-substance use behaviors.

AlcoholThe meta-analysis of the association between ED (total score) and alcohol (k = 135) revealed a statistically significant small effect (r = .190, p <.001; I2 = 93.131, Q = 1950.696, p <.001). This association differed significantly as a function of alcohol use measures (frequency (k= 11) vs. quantity (k= 10) vs. severity (k= 95), vs. problems (k= 19) (Q(3) = 36.568, p< .001). Effects were larger for problems (r = .237, 95 % CI: .148, .325, p <.001) than alcohol use severity (r = .204, 95 % CI: .175, .232, p <.001), frequency (r = .105, 95 % CI: .058, .152, p <.001) or quantity (r = .050, 95 % CI: .001, .099, p = .045).

By ED dimension, lack of emotional control exhibited the strongest association with alcohol indicators (k = 3, r = .252), followed by modulate (k = 1, r = .182), impulse (k = 71, r = .169), strategies (k = 58, r = .153), clarity (k = 58, r = .139), goals (k = 69, r = .136), non-acceptance (k = 71, r = .123), lack of awareness (k = 52, r = .063), suppression (k = 25, r = .051), other blame (k = 1, r = .040), rumination (k = 2, r = -.030), self-blame (k = 1, r = -.030), and catastrophizing (k = 1, r = .030), (Q(12) = 113.807, p < .001).

Sex did not significantly moderate the association between alcohol and ED (p = .107), but age did (β = .004, SE = .001, p = .003), with larger effects in studies with older participants. Sample type did not significantly moderate the association between ED and alcohol, with clinical samples (r = .238, 95 % CI: .173, .302, p < .001) exhibiting larger effects than community (r = .179, 95 % CI: .153, .205, p <.001) samples (Q(1) = 2.769, p = .096). Continental region did not demonstrate a significant impact on the relationship between ED and alcohol (Q(3) = 2.065, p = .559).

TobaccoThe meta-analysis of the association between ED (total score) and tobacco (k = 30) demonstrated a small statistically significant effect (r = .094, p = .001; I2 = 71.073, Q = 100.25, p <.001). This relationship did not significantly differ as a function of tobacco use measures [frequency (k= 4) vs. quantity (k= 14) vs. severity (k= 12) (Q(2) = 1.485, p = .476)]. Average effect sizes were as follows: frequency (r = .129, 95 % CI: .053, .205, p = .001), quantity (r = .069, 95 % CI: .002, .136, p = .043), and severity (r = .118, 95 % CI: .016, .220, p = .023).

In the ED dimensions, lack of awareness exhibited a stronger association across tobacco indicators (k = 12, r = .103), followed by impulse (k = 13, r = .086), non-acceptance (k = 14, r = .078), strategies (k = 13, r = .075), clarity (k = 13, r = .034), suppression (k = 2, r = .015), and goals (k = 13, r = .002), (Q(6) = 22.982, p = .001).

Sex (p = .604) and age (p = .474) did not significantly moderate the association between tobacco and ED, nor did sample type have an impact on ED (total score) estimates (Q(1) = .994, p = .319). Continental region did not exhibit a significant impact on the relationship between ED and tobacco (Q(1) = 1.715, p = .190).

CannabisThe meta-analysis on cannabis (k = 19) showed a significant relationship with ED (total score) (r = .138, p = .004; I2 = 94.400, Q = 321.448, p <.001). Differences by cannabis type measure were seen (Q(3) = 17.827, p .<.001). Effect sizes were larger for problems (k = 4, r = .372, 95 % CI: .160, .584, p =.001) than for severity (k = 4, r = .280, 95 % CI: .100, .461, p = .002), quantity (k = 2, r = .055, 95 % CI: -.033, .144, p =.222), or frequency (k = 9, r = .001, 95 % CI: -.046, .049, p =.953).

Regarding ED dimensions, impulse exhibited a stronger association across cannabis indicators (k = 6, r = .109), followed by strategies (k = 6, r = .087), lack of emotional control (k = 2, r = .060), goals (k = 8, r = .052), clarity (k = 8, r = .046), non-acceptance (k = 8, r = .031), suppression (k = 3, r = -.017), lack of awareness (k = 7, r = .008), (Q(7) = 17.304, p = .016).

Moderation analysis showed no statistically significant effects of sex (p = .906) or age (p = .153) on the relationship between ED and cannabis, but did show a statistically significant effect for sample type [Q(1) = 8.692, p = .003, (rclinical, k=4 = .346, 95 % CI: .223, .469, p <.001, rcommunity, k=13 = .094, 95 % CI: -.020, .208, p = .106)]. The participants’ continental region did not affect the association between ED and cannabis (Q(1) = 1.256, p = .262).

GamblingThe overall effect (k = 31) for the relationship between ED (total score) and gambling involvement was statistically significant (r = .228, p < .001; I2 = 84.211, Q = 190.006, p <.001). Of the gambling indicators, severity yielded the largest effects (r = .245, 95 % CI: .202, .288, p <.001) compared to problems (r = .131, 95 % CI: .077, .185, p <.001) and frequency (r = -.040, 95 % CI: -.109, .029, p =.253) (Q(2) = 48.448, p <.001). There were statistically significant differences (Q(11) = 72.756, p <.001) in the observed effect sizes by specific ED domains (see Table 1). Self-blame (k = 3, r = .400), followed by catastrophizing (k = 3, r = .257), rumination (k = 5, r = .198), impulse (k = 14, r = .191), strategies (k = 12, r = .180), other blame (k = 3, r = -.163), non-acceptance (k = 17, r = .152), lack of emotional control (k = 5, r = .140), goals (k = 17, r = .130), clarity (k = 16, r = .125), awareness (k = 16, r = .064), and suppression (k = 9, r = .056).

The moderation analyses indicated that age (Q(1) = 5.79, p = .016) moderated the relationship between ED total scores and gambling involvement. In addition, there were moderating effects of male sex (p = .004), meaning higher representation of male sex related to strengthened effects. Sample type did not moderate the abovementioned association (Q(1) = 1.668, p = .197), although continental region did (Q(3) = 14.759, p = .002). Participants from Oceania demonstrated the largest effect sizes (rOceania, k=2 = .394, 95 % CI: .312, .477, p <.001) followed by participants from Asia (rAsia, k=2 = .345, 95 % CI: .134, .555, p <.001), Europe (rEurope, k=16 = .215, 95 % CI: .146, .285, p <.001), and North America (rNorth America, k=11 = .199, 95 % CI: .121, .276, p <.001).

GamingThe relationship between ED (total score) and gaming (k = 11) was statistically significant (r = .232; I2 = 87.558, Q = 80.371, p< .001). Gaming measures focused on severity (r = .280, 95 % CI: .234, .325, p <.001) exhibited larger effect sizes than problems (r = .189, 95 % CI: .074, .305, p = .001) or time invested (r = .030, 95 % CI: -.070, .130, p = .555), (Q(2) = 20.578, p< .001).

There were differences by ED dimension (Q(11) = 61.736, p< .001). The largest effect sizes were observed for catastrophizing (k = 1, r = .288), followed by strategies (k = 6, r = .268), impulse (k = 6, r = .244), other blame (k = 1, r = .224), rumination (k = 1, r = .203), self-blame (k = 1, r = .203), lack of emotional control (k = 3, r = .189), clarity (k = 11, r = .172), non-acceptance (k = 9, r = .171), goals (k = 9, r = .145), suppression (k = 4, r = .110), and awareness (k = 11, r = .089) (see Table 1).

Moderator analyses did not reveal significant effects either by sex (p = .970) or age (p = .755). Sample type did not significantly moderate the effect sizes (Q(1) = .011, p = .915). There were no significant impacts of continental region on the association between ED and gaming (Q(2) = .166, p = .921).

Risk of biasMethodological quality assessmentComplete quality assessments for each study can be found in Supplementary Table A.3. A total of 50.79 % (n=96) of the studies showed good methodological quality (i.e., met 4-5 quality items), 30.16 % (n = 57) studies met 3 quality items, while 19.05 % (n = 36) met only 2 of the 5 quality items. On the other hand, items 3 (97.4, n = 184) and 7 (99.5 %, n = 188) were met by almost all the studies, item 1 was met by 58 % of the studies (n = 109), item 2 by 33.9 % (n = 64), and item 4 by 57.1 % (n = 108) . Low-quality ratings were due mainly to the vague definition of inclusion criteria, study subjects and setting described not in detail (especially time period), and vague definition (or lack of information) of characteristics used to include participants in the conditions. Inter-rater agreement (Cohen's Kappa) was almost perfect for items 3 and 7, substantial for item 1 and moderate for items 2 and 4.

Publication biasLow risk of publication bias was found across meta-analyses (see Table 2). Egger's test provided no evidence of asymmetry in the funnel plots, except for alcohol. The trim-and-fill analyses suggested there would be 4 and 3 unpublished studies potentially influencing the association between ED, gambling, and gaming. Jack-knife analyses showed no substantial changes and effect sizes remained similar after imputation (see Table 1).

Publication bias in the meta-analyses of emotional dysregulation (total score) by addictive behavior

This study reported statistically significant relationships between ED and all ABs. Problems and severity were the indicators that showed the strongest effect sizes in relation to ED. Sex and continental region were effective moderators of the relationship between ED and gambling. Moreover, there were stronger relationships in older participants than in younger participants (i.e., alcohol and gambling) and in clinical compared to community samples (i.e., cannabis). Minimal impacts of publication bias were found overall.

There were differences in the relationships between specific ED strategies and ABs. Both lack of strategies and difficulty in controlling impulses in the face of negative emotions were the only ED dimensions related to all substance and non-substance ABs. This maps well with the evidence supporting impulsivity conceptually overlapping the impulse dimension of ED (Willie et al., 2022) and means that difficulties in ER are in part due to impulse control behaviors, which are common in people with substance use disorders or presenting behavioral addictions (Cyders and Smith, 2008; Di Pierro et al., 2015). From this point of view, impulsivity may confer high vulnerability and prevent people envisioning possible negative consequences stemming from ABs, making it harder to access adaptive emotional regulation strategies (López-Torres et al., 2021).

Gaming and gambling were more strongly related than the other ABs to overestimation of negative emotional experiences (catastrophizing) and difficulties in impulse control (impulse). Catastrophizing of life events may confer vulnerability to gambling/gaming as a way of coping given these behaviors may serve to anesthetize disturbing emotional experiences (Melodia et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2020). On a similar note, difficulties in ER are particularly intertwined with two conditions that are prevalent in both gamblers and gamers, anxiety, and depression (Bridges-Curry and Newton, 2022; Daros et al., 2021), which also lead to risk of increased gambling/gaming by affecting how negative emotions are managed (Gerdner and Håkansson, 2022; Neophytou et al., 2023). In gamblers specifically, the prominence of these strategies may be accounted for by the many legal consequences (money lost, seizure of properties) of gambling and its negative impact on interpersonal relationships (e.g., loss of partners) (Fong, 2005). In addition, the significant relationship between self-blame strategies and gambling may be related to more severe emotional distress caused by feelings of guilt and the blame from relatives about the onset of this behavior and any ongoing relapses (Fan, 2020).

For alcohol, lack of emotional control and modulate were the ED strategies that showed the largest magnitude of effects. This suggests that alcohol users may have difficulties in reducing the intensity and the length of time they experience negative emotions. These behaviors have been related to impaired executive functions. In fact, there are several empirical studies suggesting that alcohol use hinders inhibitory control skills, which leads to difficulties in inhibiting alcohol use in the presence of alcohol-related stimuli (e.g., negative affect) (Fleming & Bartholow, 2014; López-Caneda et al., 2014).

For tobacco, lack of awareness, non-acceptance, and impulse were the ED strategies that showed the largest magnitude of effects, which suggests tobacco users would benefit from interventions providing psychoeducation on emotions. Awareness is associated with faster stress recovery following stressors (Borges, 2020). For this reason, training strategies aimed at increasing awareness of affective responses may be particularly important in that they can serve to buffer the negative symptoms associated with nicotine's pharmacological effects (e.g., increases in anxiety because of cravings). In addition, acceptance strategies to help managing urges to smoke are highly encouraged. This may include increased attention towards (and reduced avoidance of) negative symptoms through mindfulness-based and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) (Barlow & Eustis, 2022).

With regards to moderating variables, it is worth noting that, except for gambling, no association was found between sex, ED, and ABs, and this suggests ED is a risk factor for substance use and gaming regardless of sex. Age and type of population (clinical vs. community) were found to moderate several of the tested associations. The relationship between ED and alcohol was stronger in older populations, which is in line with existing research (Aldao et al., 2010). Although ER competence improves during life (Riediger and Bellingtier, 2021), it notably decreases in people with high levels of emotional activation, such as those struggling with ABs and emotional disorders (Lincoln et al., 2022).

Our findings showed a significant impact of continental region on the association between ED and gambling. Oceania, followed by Asia, Europe, and North America, exhibited the largest effect sizes. This finding is in line with research concluding that people's emotional regulation processes are shaped by culture (Ip et al., 2021; Su et al., 2015). Generally, gambling has less stigma than substance use, as its social status is judged to be higher (Dabrowska et al., 2020), which may in part account for the moderating effects seen in gambling but no other ABs. This has particular significance for Asian cultures that tend to value control overt behavior and use suppression and moderation of intense emotional experiences (Su et al., 2015). Moreover, Asian culture emphasizes the ‘interdependent self’, which suggest more dysfunctional strategies (e.g., suppression) may be deemed as culturally adaptive for the sake of harmonious social relationships (Ip et al., 2021). For western cultures, both the expression of and focus on emotional experiences may account for the larger observed estimates, as the process of enculturation in these countries emphasizes the need to foster positive emotions that include a positive sense of self and avoidance of negative emotions (e.g., sadness, depression) (Jung et al., 2009).

Interestingly, studies including clinical samples of cannabis users showed stronger associations. This is consistent with the fact that cannabis is overrepresented in people undergoing substance use treatment (Andersson et al., 2021; Pinto et al., 2019). What these results suggest is the importance of screening for ED in cannabis users and delivering ED-focused interventions to avoid falling into more severe patterns of use.

This study is not without limitations. Firstly, conducting multiple statistical tests in separate meta-analyses increases the risk of Type I error (false positives). While the random-effects approach provides some evidence for our hypothesis, it does not actually provide a truly comprehensive summary of the variables as if a single analytical model had been run. Secondly, because it examined cross-sectional relationships, no conclusions can be drawn about causality. Research on this topic is still in the early stages, and there is a need for more longitudinal studies on the association between ED and ABs before conducting a meta-analysis. Thirdly, we were unable to conduct a meta-analysis on cocaine as there was only one study that provided overall effect sizes between ED (total score) and cocaine. Other variables (e.g., ED dimensions, impulsivity, mental health disorders) were not considered as potential moderators. Virtually all studies provided data on the DERS-36 (149/189) and there was not sufficient variability in the ED measures to conduct a moderation analysis. In addition, none of the included studies provided detailed information on the presence of other mental health disorders and levels of impulsivity, and those providing such data were highly varied in terms of the variables and questionnaires they used, meaning it was not possible to analyze its moderating role. This poses an intrinsic limitation of the reviewed literature and there is need for future studies to look at individual moderators of the association between ED and ABs.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, this study supports ED as a transdiagnostic variable underlying substance use and behavioral addictions. Of the ED strategies, only a lack of strategies and impulse strategies demonstrated significant relationships across ABs. Importantly, catastrophizing was found to be common to both gambling and gaming. Health care providers are advised to evaluate ED and consider treatment protocols addressing ED that are key to each AB. Third-wave therapies, such as mindfulness-based strategies, ACT, and Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT) are promising in this capacity (Azevedo et al., 2024; Barlow & Eustis, 2022; Krotter et al., 2024), but there is still a need for further research into their potential effectiveness for both improving psychological processes (e.g., acceptance, valued oriented goals) and recovery from ABs.

Role of the funding sourceThis study was supported by the Spanish Government Delegation for the National Plan on Drugs (ref. 2020I003) and by a predoctoral grant from the Government of the Principality of Asturias (ref. PA-21-PF-BP20-015). The funding sources had no role other than financial support.

Meta-analysesThe references ⁎indicates the studies that were included in the meta-analyses.

- Download PDF

- Bibliography

- Additional material