A Study related to Safety in Hospitals in the Region of Madrid (ESHMAD) was carried out in order to determine the prevalence, magnitude and characteristics of adverse events in public hospitals. This work aims to define a useful methodology for the multicenter study of adverse events in the Region of Madrid, to set out the preliminary results of the hospital enrollment and to establish a model of a strategy of training of trainers for its implementation.

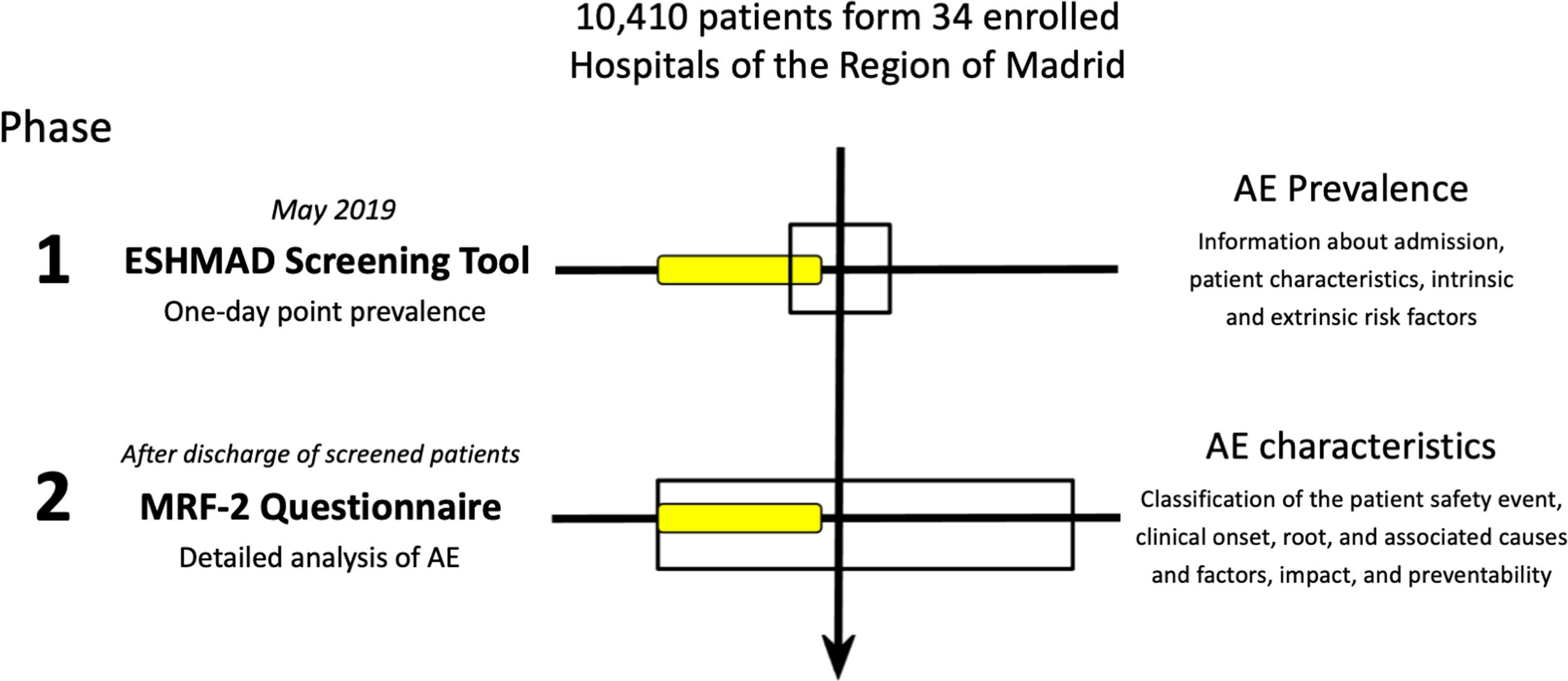

MethodsESHMAD was a multicenter, double phase study for the estimation of adverse events and incidents prevalence across the Region of Madrid. First phase comprehended a 1-day cross-sectional prevalence study, in which it was collected, through a screening guide, information about admission, patient characteristics, intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors, and the possibility of an adverse event or incident had happened during the hospitalization. Second phase was a retrospective nested cohort study, in which it was used a Modular Review Form for reviewing the positive screenings of the first phase, identifying in each possible adverse event or incident the classification of the patient safety event, clinical onset, root, and associated causes and factors, impact, and preventability. A pilot study was performed in an Internal Medicine Unit of a tertiary hospital.

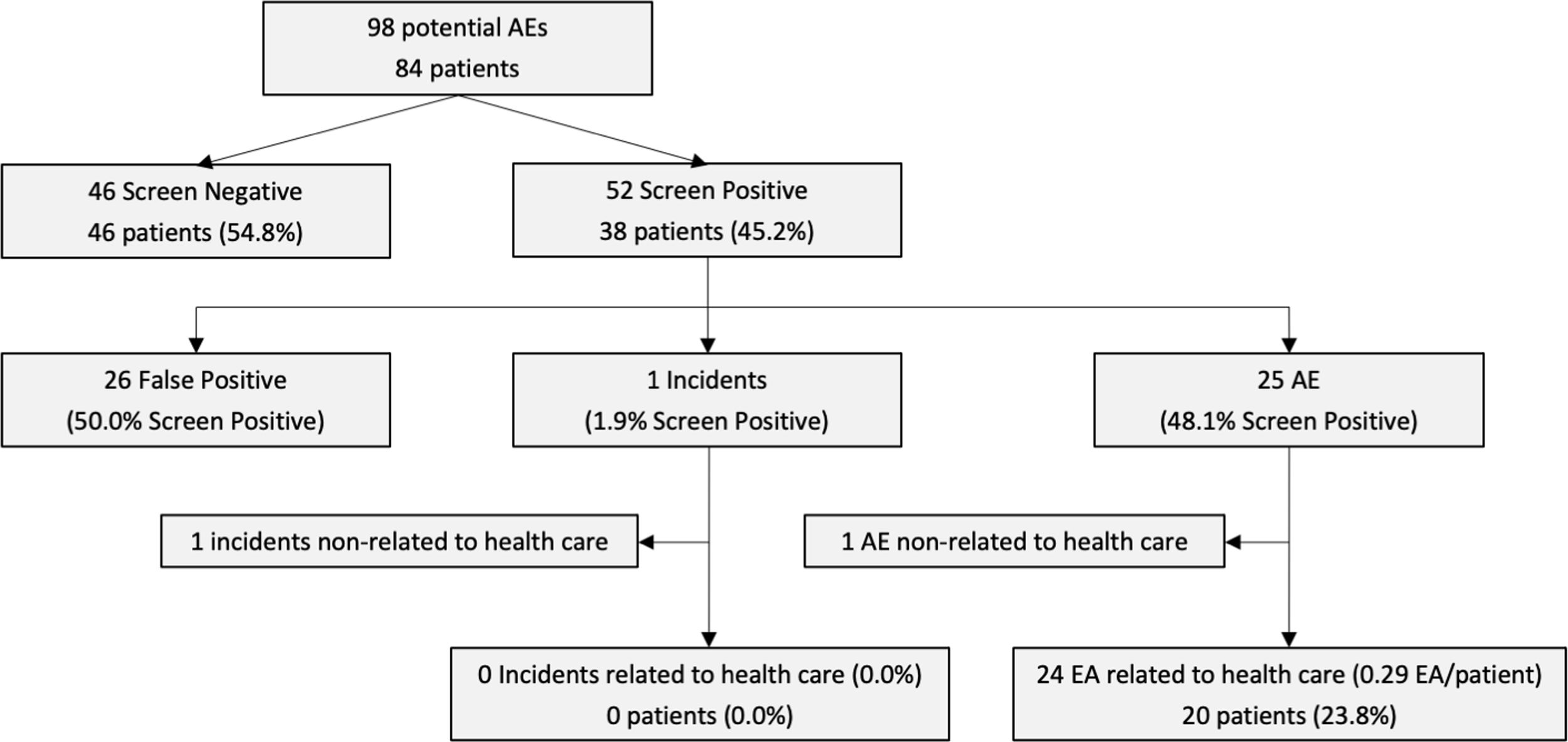

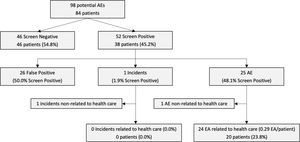

Results34 public hospitals participated, belonging to 6 healthcare categories and with more than 10,000 hospitalisations aggregate capacity. 72 coordinators were enrolled in the strategy of training of trainers, which was performed through five on-site training workshops. In the pilot study, 45.2% patients were identified with at least one positive event of the screening. Of them, 48.1% (25 positive events) were identified as truly AE, with a result of 0.29 EA per analyzed patient.

ConclusionsThe ESHMAD protocol allows to estimate the prevalence of adverse events, and the strategy of training of trainers facilitated the spread of the research methodology among the participants.

El Estudio sobre la Seguridad de los Pacientes en Hospitales de la Comunidad de Madrid (ESHMAD), fue desarrollado para estimar la prevalencia, magnitud y características de los eventos adversos en hospitales públicos. Este trabajo pretende definir una metodología útil para el estudio multicéntrico de eventos adversos en hospitales de la Comunidad de Madrid, exponer resultados preliminares sobre el conjunto de los hospitales reclutados y establecer un modelo de estrategia de preparación de formadores para su implementación.

MétodosESHMAD fue realizado como un estudio multicéntrico de doble fase para estimar la prevalencia de eventos adversos e incidentes de seguridad. La primera fase consistió en un corte transversal en el que se recopiló, a través de una guía de cribado, información del ingreso, características del paciente, factores de riesgo intrínsecos y extrínsecos, y la posibilidad de que haya ocurrido un incidente o evento adverso durante la estancia. La segunda fase fue un estudio retrospectivo de cohorte anidada en el que se utilizó un formulario de Revisión Modular para los cribados positivos, identificando en cada posible incidente o evento adverso el tipo de evento de seguridad del paciente, características clínicas, causas, factores asociados, impacto y evitabilidad. Se realizó un estudio piloto en una Unidad de Medicina Interna de un hospital de tercer nivel.

ResultadosParticiparon 34 hospitales públicos, pertenecientes a seis niveles asistenciales y con una capacidad conjunta mayor de 10.000 pacientes ingresados. Se reclutaron 72 coordinadores para la estrategia de preparación de formadores. En el estudio piloto, un 45,2% de los pacientes presentaron al menos un ítem durante el cribado. De ellos, el 48,1% se consideraron verdaderos eventos adversos, con un resultado de 0,29 eventos adversos por paciente.

ConclusionesEl protocolo ESHMAD permite estimar la prevalencia de eventos adversos y la estrategia de preparación de formadores facilita la difusión de la metodología del proyecto entre los participantes.

Adverse events (AE) and incidents were brought into the spotlight by the Harvard Medical Practice Study, and then by the Institute of Medicine publication To Err is Human.1,2 It's been almost two decades since then, and other epidemiological studies in several countries replicated this method to estimate AE. However, other complementary approaches have been also developed, such as the analysis of complaints and claims or incident reporting and learning systems.

The Harvard Medical Practice Study (HMPS)2 was one of the firsts attempts to elucidate AEs and nowadays has become the benchmark method for research on adverse events in hospitals.3 It was based on a two-stage chart review: in the first stage, patient records that were likely to include an adverse event were screened; in the second, through the Modular Review Form for retrospective case record review (MRF-2), selected charts were reviewed in more detail to confirm the presence of adverse events, and to assess the extent to which these events indicate substandard care.4

Other studies subsequently replicated this way of AE estimation in different countries.5–7 In Spain, the Spanish National Study of Adverse Events (ENEAS)8 estimated the incidence of AEs and incidents in hospitals, with a national, but not regional representativeness. ENEAS was designed as a retrospective cohort study, adapting the HMPS method to screen incidents and AEs, and the MRF-2 questionnaire to perform a comprehensive analysis of its characteristics, impact, and preventability. Other studies adopted different approaches, like the Iberoamerican Study of Adverse Events (IBEAS), which used a cross-sectional design, with similar questionnaires to screen and analyze AEs and incidents, to estimate AE for the first time in Latin American countries.9

On the other hand, cross-sectional studies require less time, are more cost-efficient and, although it doesn’t allow us to study the whole hospitalization period, it has proven to be capable enough to support a more stable in time vigilance system.10,11 An example of this would be the Prevalence of Adverse Events related to Hospitalization in the Valencian Region (EPIDEA),12 which was able to become a stable epidemiological method for over a decade to analyze AEs in all hospitals of the Valencian Region. This design has also been used by other studies related to patient safety, as the Prevalence Study of Nosocomial Infections in Spain (EPINE), which, since the 1990s, has been the first study to estimate risk factors and prevalence of healthcare-associated infections at a national and regional level.13

However, these studies are good opportunities not only for knowing the patient safety situation of a healthcare center or a health system but also for improving the training of healthcare professionals and to imply them in this field. In this context, the Study on Safety in Hospitals in the Region of Madrid (ESHMAD) was designed. This study, inspired by the EPIDEA protocol, also adapted and optimized its paper-based tools and selection criteria, as well as included improvements in data collection and professional's training.

The objective of this work was to define the methodology of the ESHMAD, developed to estimate the prevalence, magnitude, and characteristics of adverse events in public hospitals, as well as to set out the preliminary results of the hospital enrollment and to establish a model of a strategy of training of trainers for its implementation.

MethodsStudy designESHMAD was a multicenter, double phase study that comprehended a 1-day cross-sectional prevalence study and a retrospective nested cohort study to estimate AE prevalence. This study was developed in the Region of Madrid, a geographic territory with an area of more than 8000 squared kilometers and 6,600,000 inhabitants, whose main city is Madrid. This Region contains 34 public hospitals and 49 private hospitals, with 12,247 and 6819 functional beds, respectively.

All the public hospitals of the Region of Madrid, regardless of their capacity, received an invitation through the Health Department of the Region of Madrid Public Administration for participating in the study.

In this project, to avoid selection bias,14 all patients hospitalized in one single day (phase one: 1-day point prevalence) were taken into consideration. Each bed, as one day of hospital stay, was screened looking for possible patient safety incidents or AE, using a questionnaire of 18 items adapted from previous studies.2,8,9 Following, all cases with some positive screening criteria were reviewed using the medical record and an adapted paper-based MRF-2 questionnaire.4

Patient populationAll patients hospitalized before 8:00a.m. the day of the study fulfilled inclusion criteria for screening, regardless of the service, condition, or hospital stay. Patients hospitalized in a single medical department were studied on the same working day, excluding those patients temporarily displaced to other departments and did not return to this service. Beds were taken into account as physical locations of each patient and were examined only once. Not occupied beds during the data collection day were not taken into consideration for the study, and each service was methodologically screened to avoid duplicates or enrollment of empty beds.

Variables assessedThe AE definitions used in both designs were those published by WHO in the International Classification for Patient Safety.15 A patient safety incident was an event or circumstance that could have resulted, or did result, in unnecessary harm to a patient. An AE or harmful incident was an incident that resulted in harm to a patient that differs from his underlying condition. An avoidable AE or avoidable incidents were those incidents that could have been prevented if proper measures would have been taken.

To obtain this information, the medical records were analyzed by trained professionals who used a six-point scale to determine whether an AE was related to medical care. In this scale, the “1” value meant no evidence attributable to medical care, and the “6” value meant almost certain evidence attributable to medical care; considering a score of at least 4 out of 6 points as a positive association between the incident and the medical care. The same scale and interpretation were applied to determine the preventability of AE or incidents.

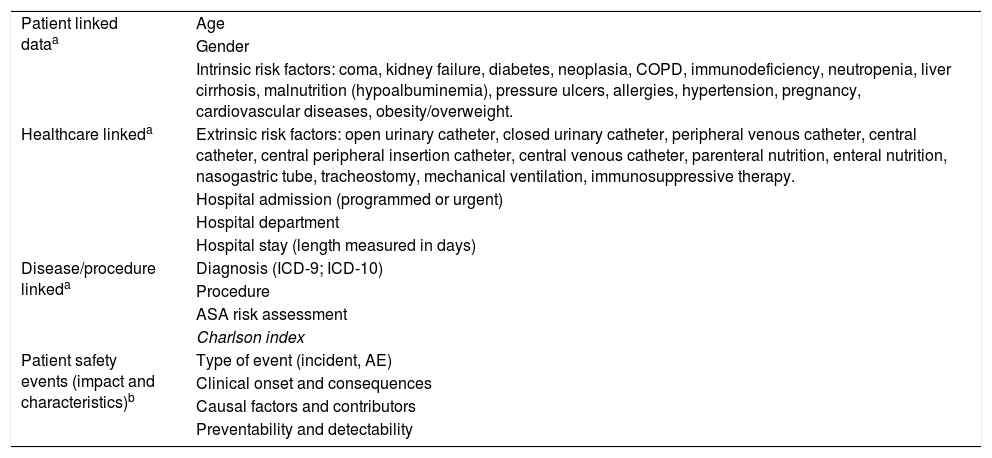

InstrumentsThe ESHMAD used two paper-based questionnaires. First, for the cross-sectional method, an adapted review question sheet from the IBEAS16 protocol screened all hospitalized patients to capture possible AEs (available as supplemental material), that were subsequently analyzed in Phase 2. For medium stay and psychiatric hospitals, the following records were not considered: criteria related to hospital transfers, second surgical procedures during the hospital stay, and complications with labor and delivery; due to not correspondence with the institution's capabilities. During this first phase, the screening guide collected information about admission, patient characteristics, intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors, and the possibility of an incident or AE had happened during the hospitalization. Eighteen criteria concerning possible patient-related incidents were checked, including information about the previous admission and possible incidents (such as treatment management, complications, transfers, AEs) of the ongoing hospitalization (Table 1). A licensed nurse with previous training could execute this task for all hospitalized patients. Hospital Units were notified to act if a healthcare resolvable AE is identified during this phase.

Independent variables collected in the study.

| Patient linked dataa | Age |

| Gender | |

| Intrinsic risk factors: coma, kidney failure, diabetes, neoplasia, COPD, immunodeficiency, neutropenia, liver cirrhosis, malnutrition (hypoalbuminemia), pressure ulcers, allergies, hypertension, pregnancy, cardiovascular diseases, obesity/overweight. | |

| Healthcare linkeda | Extrinsic risk factors: open urinary catheter, closed urinary catheter, peripheral venous catheter, central catheter, central peripheral insertion catheter, central venous catheter, parenteral nutrition, enteral nutrition, nasogastric tube, tracheostomy, mechanical ventilation, immunosuppressive therapy. |

| Hospital admission (programmed or urgent) | |

| Hospital department | |

| Hospital stay (length measured in days) | |

| Disease/procedure linkeda | Diagnosis (ICD-9; ICD-10) |

| Procedure | |

| ASA risk assessment | |

| Charlson index | |

| Patient safety events (impact and characteristics)b | Type of event (incident, AE) |

| Clinical onset and consequences | |

| Causal factors and contributors | |

| Preventability and detectability |

COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; ICD: International Classification of Diseases; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists. AE: adverse events.

The second phase started at the patient discharge, or 30 days later if this had not occurred. Then, for all those records with one or more positive results of the eighteen screening criteria, an exhaustive analysis was carried out using an individual MRF-2 questionnaire4 (one for each incident or AE detected since a single patient could have more than one; available as supplemental material). Thus, the following items were performed through medical records by trained physicians with experience in patient safety management: the classification of the patient safety event, clinical onset, root, and associated causes and factors, impact, and preventability (Fig. 1).

The following graphic schematizes the ESHMAD study protocol and its benefits: to the left, tool and method; to the right, results. In phase 1, the screening tool allowed us to capture a possible AE (yellow box). In phase 2 (at discharge or 30 days after the initial screening), with the MRF-2 questionnaire, the characteristics and impact of the AE were elucidated. AE: Adverse Events; ESHMAD: Study on Safety in Hospitals in the Region of Madrid; MRF-2: Modular Review Form for retrospective case record review.

Each hospital also performed voluntarily an additional register of data with every negative screened review. Through this approach, the available data from all patients (with or without AEs) was obtained and allowed the researchers to determine the baseline risk.

Project planningCompleted paper-based forms were transcribed in a web-based and encrypted platform from the adaptation and improvement of a tool previously designed for the EPIDEA project, the “Sistema de Vigilancia y Control de Eventos Adversos” based in “Base de Datos SVCEA 1.0 – IDEA 4.0”.

This study was performed in 2 phases: Phase 1, developed during May 2019 and coinciding with the EPINE study, which included the AE or incident screening guide, the intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors, or the data administrative aspects of hospital admission. Phase 2, that began after the discharge of each patient screened, or at least 30 days after it, in which the detected AE or incident was analyzed and characterize the patient's baseline risk.

A strategy of training of trainers was carried out to ensure the correct understanding of the organization and development details, and to unify AE concepts and clarify doubts regarding the tools or database.

Pilot testingA pilot study was performed in the second week of May 2019 (simultaneously with the EPINE research project) in an Internal Medicine Unit of a tertiary hospital of the Region of Madrid. The hospital had 822 functional beds capacity and a 79.2% hospital occupancy rate at the study time.

Data processingData was stored in the previously mentioned application and bases for its proper management only by the principal investigator. Subsequently, the data will be treated with the statistical software Stata® to conduct descriptive and multivariate analysis. Logistic regression will elucidate how different variables are modifying adverse events.

Study outcomesValuable information concerning the occurrence of AEs was collected. During the first phase, point-prevalence and the main characteristics were elucidated for each hospital and the Madrid Region. And, in the second phase, the MRF-2 provided with AEs impact over patient's health and what it represents to each hospital.

EthicsThe study was approved for the consideration of the Ethics and Research Committee of the Ramón y Cajal Institute of Health Research, ensuring the necessary conditions to guarantee compliance with the corresponding Laws/regulations of the countries on Protection of Personal Data: Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and the Council of April 27th, 2016 of Protection of Data (RGPD) and the Organic Law 3/2018, of December 5th, of Protection of Personal Data and guarantee of digital rights.

Also, on behalf of the group of researchers of the project, it was assumed the commitment to conduct research ensuring respect for the principles set out in the Declaration of Helsinki, the Convention of the Council of Europe (Oviedo) and the Universal Declaration of UNESCO.

All participants in the study were required to maintain confidentiality about the information they had access during the study, as in any other of their professional activities. This included a randomized ID assignment of every screening tool collected in the encrypted web-based application and the proper custody of paper questionnaires. The presentation of data was always added, in such a way that, in no case, from the diffusion of data no one could reach the identification of a patient.

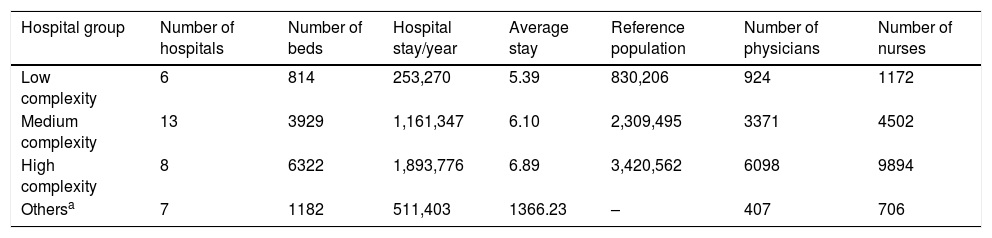

ResultsSample enrolledIn total, 34 public hospitals belonging to six healthcare categories across the Region of Madrid were enrolled for this study, including six low complexity hospitals, 13 medium complexity, eight high complexity, two support hospitals, three medium-to-long-stay hospitals, and two psychiatric hospitals. The whole capacity of these hospitals was 12,247 functional beds, which corresponded to 10,410 potential enrolled patients (Table 2).

Characteristics of enrolled hospitals.

| Hospital group | Number of hospitals | Number of beds | Hospital stay/year | Average stay | Reference population | Number of physicians | Number of nurses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low complexity | 6 | 814 | 253,270 | 5.39 | 830,206 | 924 | 1172 |

| Medium complexity | 13 | 3929 | 1,161,347 | 6.10 | 2,309,495 | 3371 | 4502 |

| High complexity | 8 | 6322 | 1,893,776 | 6.89 | 3,420,562 | 6098 | 9894 |

| Othersa | 7 | 1182 | 511,403 | 1366.23 | – | 407 | 706 |

In most cases, the Preventive Medicine and Public Health Units and the Health Care Quality Units, each of them with one designated group coordinator, performed the first and second phases, respectively. That implies that the first phase was executed by physicians and nursery staff, while the second phase was mainly performed by physicians (including medical residents) specifically trained in Patient Safety. Of the 34 public hospitals enrolled, one of them had four coordinators, and another had three. Thus, 71 coordinators were enrolled, 35 in charge of coordinating the first phase (screening of possible AE or incidents), and 36 more in charge of coordinating the second phase (retrospective nested cohort study for reviewing the positive screenings of the first phase). The role of these coordinators was to oversee the research team recruitment and training, specific fieldwork planning, and proper preparation and validation of data collection.

In order to establish main strategies and ensure homogeneity in the filling process, complete training was arranged for the designated coordinator. The training was performed throughout April 2019, in an on-site 8h theoretical-practical course which was repeated during five days in order to ease the attendance of all study coordinators. The training course was divided into two main sections: a first theoretical part, and a practical process of simulated cases. The theoretical classes aimed to give straightforward concepts of the process followed to complete the final project. In this regard, this section of the program was divided into four sets of materials (presentations on basic concepts, organization and design of the study, and specific aspects of phase 1 and phase 2, related scientific articles). In the beginning, introductory concepts of patient security, the main purposes of the study and the methodology followed were explained. Subsequently, the coordinators were given specific instructions to fulfill the screening guide, explaining the whole requirements to complete it, and verifying the need of concluding with the MDFR-2 (only in case the screening result was positive). At the end of this theoretical section, functional bibliographic resources were facilitated to the coordinators to complement the information previously exposed.

To accomplish training main objectives, the course was followed by a practical section. By means of the EPIDEA project database coordinators performed simulated cases in the project web platform. Coordinators had to complete a screening guide with fictional patient data following the steps previously proposed in the theoretical part. It was provided all the information needed, for example clinical details, in order to ensure a realistic performance.

All the content of the course was loaded in an electronic link on Internet, to simplify the access and promote their visualization of all the coordinators that had to train their own research team.

Pilot studyIn the pilot study performed over an Internal Medicine Unit of a tertiary hospital, 84 patients met the criteria to be included in the 1-day cross-sectional prevalence study of the first phase. Of them, 46 (54.8%) patients did not meet any item of the screening guide, while 38 patients (45.2%) were identified with at least one positive event of the screening. Through the second phase, using the MRF-2 questionnaire, 25 positive events (48.1%) were identified as truly AE, 1 (1.9%) as incident, and 26 (50.0%) as false positive screenings. Finally, 24 EA were considered related to healthcare assistance, which implies a result of 0.29 EA per analyzed patient (Fig. 2).

DiscussionMany studies have considered diverse methodologies to analyse the impact of adverse events related to patient safety in clinical practice. Among them, prevalence estimation method appears to be the most efficient. Determining a convenient study design is crucial to assure a high-quality execution and relevance in public health research, taking into consideration its final objectives to accomplish minimal bias and correct validity of its results and statistical method for data analysis.14

Several researches have established prospective studies to measure patient safety problems because of their major efficacy in identifying more AEs.17 Nevertheless, this design entails a number of challenges to face during the study development. First, the long period needed to record the data and the requirement of very detailed information implies an arduous task that can affect the methodologic quality, generating more bias. In this respect, the lack of complete information in medical records due to the demanding daily practice makes more clinicians tend to record the data more meaningful for them. Furthermore, the more sophisticated sampling with the tremendous effort required for good data collection and the need for more resources assume a high workload. For all the above reasons, planning a prospective study suppose a substantial cost.

Conversely, the cross-sectional studies are more cost-efficient and faster performed because of the sort period time collected being more easily replicable as a vigilance system over different editions.10,11

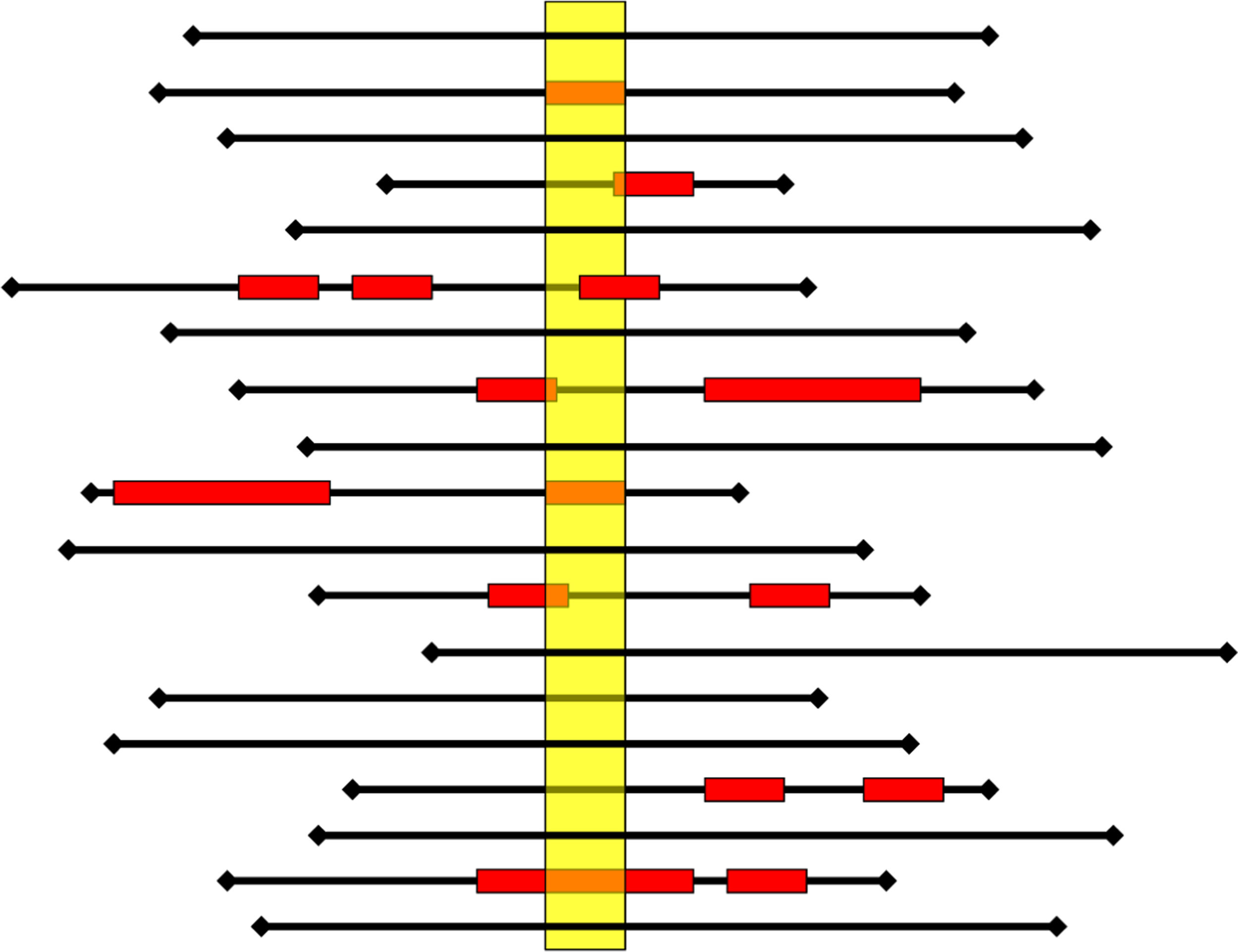

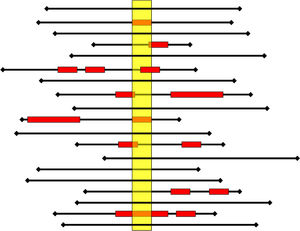

The cross-sectional study can be repeated sequentially (at least annually) and periodically, which will allow in the future to perform panel studies. Moreover, it adequately estimates the presence of AE in clinical practice. Thus, Fig. 3 illustrates the AE detection record among different cross-sectional studies. In this example, the prevalence study would not discriminate 6% of the cases detected in traditional retrospective review studies.18

Each black line represents the hospitalization (length of stay) of a patient; the red box represents adverse events (AE) (onset, duration, and end). The yellow rectangle represents the cross-sectional (1-day point prevalence). A prevalence study would detect seven patients with AE of 19 patients (Prevalence=37%, 47% of AE cases identified). A retrospective review study, which usually only considers the most severe AE that the patient has tended, would detect 8 of 19 patients with AE (incidence=42%, detection of 53% of the AE).18

This efficient and effective patient safety assessment methodology, adapted to the characteristics of the hospitals of the Region of Madrid, would contribute to knowing the frequency, nature, and predisposing and contributing factors of the AEs; to plan monitoring and surveillance strategies; and to guide the policies and activities aimed at their prevention.

Nationwide, ESHMAD has been the first attempt to collect AEs data from an entire region since EPIDEA integrating and optimizing efforts and resources developed in previous studies. Contrary to EPINE and other international initiatives, the protocol includes all related patient safety incidents and not only healthcare-associated infections and use of antibiotics. Throughout this method, data from impact, characteristics, preventability, and prevalence is estimated providing additional value.

Besides, the development of the first phase of ESHMAD simultaneously with the EPINE had multiple advantages: first, it allowed us to collect the data efficiently at one time for the two studies since both share common study variables; second, all the nosocomial infections identified and studied in the EPINE could be directly interpreted as adverse events in the ESHMAD; third, the epidemiological features of the final ESHMAD sample could be reviewed and compared with the obtained results of previous EPINE editions.

Moreover, the combination of the ESHMAD protocol (providing prevalence, characteristics, impact, and preventability of the AE) with the analysis of claims filed (for detecting latent errors) and the implementation and use of an incident notification system could reduce the gap between asserted policies for healthcare improvement.

Developing a surveillance study to estimate patient safety situation should go further than accurately estimate the incidence or prevalence of AE. It should encourage patient safety culture through the exhaustive analysis of problems, transforming these into means for learning and setting priorities. Thus, although this protocol requires time and expertise of physicians to be executed, this is able to provide to the set and each of the hospitals a group of trained professionals in AE analysis. Besides, it enhances the addressing of one of the objectives proposed by the Madrid's Region Patient Safety Strategy 2015–2020, which is to develop and fortify a unified patient safety incidents related notification system and improve quantitative and qualitative data collection due to the involvement of the Functional Health Risk Management Units of each hospital in the present study.19 This allows a combined task force in patient safety in each hospital, integrating efforts coming from multidisciplinary services with a common goal, to reduce AEs.

LimitationsA common inconvenience in epidemiological studies of this magnitude is the data availability, which can be scarce, containing poor quality information, and very dependent on the professional that collect it.

The subjective nature of the MRF-2 questionnaire was an intrinsic limitation in the process, mainly because it implies the judgement of the reviewer about the medical information available.

Although we tried to homogenize concepts with the training of researchers, using the same approach as other studies,20 we could not ensure the information provided by the coordinators to their own research teams after the training. An appropriate way to alleviate this problem could be to provide training to all the researchers responsible for data collection.

Moreover, the success of this study was hindered by the individual circumstances of every patient involved in the study which makes challenging to assess every case in particular. This bias could be alleviated in future editions when we have more information about different cases establishing a uniform strategy of performance.

It must be accounted for a possible survival bias, due to hospital admissions because of an AE, and those related to healthcare infection or those that were difficult to identify if the patient was not seen (such as contusions), due to the nature of the prevalence study. Similar to prospective studies, the communication with the plant staff or the review of the patient (who was hospitalized at that time), favored the judgment of the causality of the adverse effect and its preventability.

ConclusionThe ESHMAD study is a cross-sectional method that aims to become a surveillance system (executed every year) to assess the temporal evolution of the prevalence of AE in hospitals of different complexity of the Region of Madrid. Its performing simultaneously with the EPINE allows to collect the data efficiently and the strategy of training of trainers facilitated the spread of the research methodology among the participants.

FinancingThe ESHMAD was carried out at the regular working time of the participating researchers, with the commitment of the directors of each enrolled hospital. Thus, no researcher obtained additional remuneration to his ordinary contract. In the same way, it did not exist specific funding for the web platform, since its server belonged to the public administration. This research has not received specific funding from commercial sectors agencies or non-profit entities.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Asunción Colomer Rosas, Inmaculada Mediavilla Herrera, Mª José Esteban Niveiro, Nieves López Fresneña, Cristina Díaz-Agero Pérez, Pedro Ruiz Lopez, Isabel Carrasco Gonzalez, Cristina Navarro Royo, Carmen Albéniz Lizarraga, Yuri Fabiola Villan Villan, Ana Isabel Alguacil Pau, Alicia Díaz Redondo, Rosa Plá Mestre, Dolores Martín Ríos, Angels Figuerola Tejerina, Carlos Aibar Remón, José Joaquín Mira Solves.