Co-creation 5.0 is a new era in which frontline employees (FLE) and service robots work as a team. This study examines the consequences of co-creation 5.0 on service outcomes in a real context and analyses the moderating effect of the FLEs and collaborative service robot (CSR) teams. We employed the attribution theory as the conceptual framework. Moreover, we studied the relationships between two service outcomes (perceived value of the firm and word of mouth (WOM) intention about the firm), two explanatory variables related to the two agents (perceived competence of FLEs and satisfaction with human–robot interaction (HRI), and the moderating effect of the FLE–CSR team. An empirical investigation was designed involving two CSRs that provided customers with information for one week each in two hotel lobbies. Qualitative research was conducted through observations and personal interviews with employees and customers. Customer evaluations were performed using a questionnaire based on scales validated in the literature. The findings show that in the current state of technology, in the context of co-creation 5.0, the FLE is primarily responsible for the firms’ outcomes from the customer perspective. The CSR is seen as a service delivery team member with a complementary character. However, personnel have negative opinions about CSRs and do not regard them as partners. However, customers assign responsibility to CSR, and an increase in their social–emotional skills leads to increased attribution of responsibility.

In recent years, research on service robots has soared (Xu et al., 2023; Le et al., 2023). Although it is assumed that robots will replace workers in many jobs, a common scenario is the collaboration between frontline employees (FLE) and service robots (CSR) in a manner that they complement (de Kervenoael et al., 2019; Ho et al., 2020; Lu et al. 2020; Paluch et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2023; De Gauquier et al., 2023; Le et al., 2023). Subsequently, service robots will replace or augment the role of FLE (Khoa et al., 2023; De Gauquier et al., 2023). Noble et al. (2022) refer to the fifth industrial revolution, distinguishing it from the fourth by emphasising harmonious collaboration between humans and machines. Unlike the competitive nature of the previous revolution, this new era focuses on the well-being of humanity.

Therefore, augmented services (collaboration between FLE and CSR) could be a common scenario in the service industry (Phillips et al., 2023; Khoa et al., 2023; De Gauquier et al., 2023; Kraus et al., 2023). Khoa et al. (2023) estimate that at least 30% of the current service sector jobs will become augmented services. In sectors such as hospitality, the FLE–robot collaboration is expected to improve productivity, quality, operational efficiency, and employee well-being (Wirtz et al., 2018; Lakshmi & Bahli, 2020; Chong et al., 2021; Raisch & Krakowski, 2021; Lin & Mattila, 2021; Xu et al., 2023). However, integrating service robots into service co-creation currently generates more work and concerns for FLEs than it saves (Phillips et al., 2023).

Introducing service robots to customer service and sharing tasks with FLE is a major challenge for many organisations (Lakshmi & Bahli, 2020; AlQershi et al., 2023; Holthöwer & van Doorn, 2023; Phillips et al., 2023). Robotics significantly impacts business strategies, governance structures, organisational culture, and labour relations (Kraus et al., 2023). The challenge of augmented service must be addressed because a company's competitive advantage lies not only in incorporating innovations such as service robots but also in developing new routines, capabilities, and technological interdependencies and aligning employees’ skills with the company's innovation strategy (Kraus et al., 2023). This emerging perspective in research has coined concepts, such as ‘frontline employee–robot interdependence’ or ‘human–robot cooperative interaction’, which focus on the management of collaboration between both agents (Lu et al., 2020; Paluch et al., 2022; Le et al., 2023). In tourism, the concept of ‘Hospitality 5.0’ can be generalized to ‘Co-creation 5.0’. This new era envisions FLEs and service robots collaborating as a team with a human-centric orientation. It emphasises resilience, well-being, and sustainability (Adel, 2022; Noble et al., 2022).

Table 1 (appendix) reviews the most recent literature on co-creation 5.0. A significant number of studies have examined customer perceptions of the FLE-CSR team, whereas another group of studies has focused on employee perceptions of CSR. Special attention has been paid to the study on the acceptance of service robots (intention to use) by customers or employees using theories such as technology affordance theory, TPB, and technology acceptance model (TAM). However, we have not identified any study on joint perceptions of customers and FLEs concerning augmented services (360° view). The analysis of Table A1 also shows that most research on augmented services has focused on establishing customer preferences for the two actors, with surveys and lab experiments being the most commonly used empirical methodologies. However, the impact of the FLE-CSR team on firm outcomes has rarely been studied, and few studies have been conducted in laboratory settings (not in a real service context). For example, an experiment by Jiang et al. (2022) study customer purchase intention when the service was operated by a human or humanoid. Another experiment by Wu et al. (2023) analyse consumers' willingness to pay more based on whether the service was provided by an FLE or CSR. De Gauquier et al. (2023) use a video survey to study the retail sales conversion ratio of the FLE-CSR team.

In short, augmented services deserve the attention of researchers; however, the 360° view and consequences of co-creation 5.0 have hardly been studied (Phillips et al., 2023; Le et al., 2023; Paluch et al., 2022; Chong et al., 2021; Ho et al., 2020; Wirtz et al., 2018; Van Doorn et al., 2017). How the FLE–CSR team contributes to creating value for the company or to generating word of mouth (WOM) in a real service situation are key aspects of co-creation 5.0 research that have not yet been studied (Ho et al., 2020; Lin & Mattila, 2021). Le et al. (2023) believe a research gap exists since no frameworks provide guidance on how this collaboration should be designed. Further, Kraus et al. (2023) call for research into the future of work based on the ability of people and organisations to adapt to new technological environments.

This study aims to examine consequences of co-creation 5.0 on service outcomes in a real context and analyse the moderating effect of the FLE–robot team. We use attribution theory as a conceptual framework, allowing us to justify the causal relationships between two service outcomes (perceived value of the firm and WOM intention about the firm) and two explanatory variables related to the two agents (perceived competence of FLEs and satisfaction with HRI). The research approach can be summarized in three research questions:

RQ1: How does the augmented service (FLE–CSR team) affect service outcomes (perceived value of the firm and WOM about the firm)?

RQ2: To which agent of the FLE–CSR team does the customer attribute most responsibility for service outcomes?

RQ3: What are the perceptions of customers and FLEs regarding augmented service?

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. First, a literature review is conducted, wherein the theoretical background of attribution theory is presented. Next, we justified our hypotheses. We designed an empirical investigation using two service robots that provided information to customers for one week each in two hotel lobbies. Customer evaluations were conducted using a questionnaire based on scales validated in the literature. Moreover, additional qualitative research was conducted through observations and personal interviews with customers and employees. The results are then presented. Finally, a discussion and conclusions of the study are presented.

Theoretical backgroundAttribution theoryService robots are defined as ‘autonomous and adaptable interfaces that interact, communicate and deliver service to an organisation's customer’ (Wirtz et al., 2018, p. 909). The recent line of research on co-creation 5.0 has led some authors to define CSRs as ‘embodied machines equipped with some degree of artificial intelligence (AI) and functional autonomy that are designed to work alongside FLEs and perform similar service roles as their human counterparts’ (Paluch et al., 2022, p. 365).

The conceptual framework chosen to analyse the joint impact of FLEs and robots on service outcomes is the attribution theory (Heider, 1958; Kelley, 1973). This theory explains the causality of an observed event or behaviour based on internal and external factors. In a service delivery scenario, customers seek a causal explanation of the outcomes: they want to understand why things have happened to control and predict their behaviour (Weiner, 2000; Belanche et al., 2020; Arikan et al., 2023). Consumers make causal attributions by observing the conditions surrounding a service, the available information, and their beliefs and motivations (Belanche et al., 2020).

In service management, attribution theory has mostly been used to identify the causes of service failure (Iglesias, 2009; Hartmann & Moeller, 2014; Tam et al., 2014; Leung, Kim, & Tse, 2020); however, the literature has also demonstrated its usefulness in explaining the causes of satisfaction, loyalty, and positive WOM (Belanche et al., 2020; Arikan et al., 2023). Attribution theory considers three dimensions that customers deliberate on when assigning attributions: the locus of causality, controllability, and stability (Weiner, 1979; 1986). Locus of causality refers to who or what could be the main cause of success or failure in providing a service. Controllability indicates whether the responsible agent can change the course of service delivery. These two dimensions are often grouped under responsibilities (Belanche et al., 2020). Finally, outcome stability refers to the degree of performance attributed to the perceived cause of a service's success or failure, namely, the probability that the same outcome will occur again.

In a co-creation 5.0 scenario, the customer considers FLEs and CSRs as responsible actors (Bitner, 1990; Hess et al., 2007; Belanche et al., 2020; Arikan et al., 2023). However, the existing differences between the two agents have implications for customer attribution. Human–human interaction differs from HRI because the human–human interaction involves a) understanding the feelings, thoughts, and motivations of others; b) sharing knowledge, beliefs, and assumptions; c) empathising with the other party; and d) assuming the other's ability as an intentional agent whose behaviour is influenced by states, beliefs, and desires (Carruthers & Smith, 1996; Belanche et al., 2020). Thus, human–human interaction has a social–emotional component that HRI lacks (Phillips et al., 2023).

Belanche et al. (2020) show that customers attribute less responsibility for a service outcome to CSRs than to FLEs because, in the current state of technology, neither a significant degree of moral autonomy nor social–emotional capacity can be ascribed to them. However, the literature considers that customers attribute more outcome stability to CSRs than to FLEs (Casado & Mas, 2002; Iglesias, 2009). The standardisation provided by technology does not depend on an individual's mood, fatigue, personality, or attitude towards work, implying that CSR behaviours are predictable (Belanche et al., 2020).

Service outcomes, FLE competence, and HRIHo et al. (2020) consider that the degree to which different actors involved in delivering a service play social roles is critical for service evaluations and outcomes. In this study, two service outcomes (perceived value of the firm and the firms’ WOM intention) and two antecedent variables representative of the two agents studied (perceived FLE competence and satisfaction with HRI) are chosen (Table 2).

Variables definitions.

| Variable | Definition | Refs. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FLE | Perceived FLE competence | The degree to which a customer feels that FLEs’ efficiency, friendliness and professionalism stimulate their senses | Khan and Rahman (2017) |

| CSR | Satisfaction with HRI | HRI: information and action exchanges between humans and robots to perform a task through a user interface (vocal, visual, or tactile)Satisfaction with HRI: comparison of customer perception and expectations about HRI | ISO (2021)Moliner-Tena et al. (2023) |

| Service outcomes | Firms’ perceived value | Value for money received by the customer from the firm | Sánchez et al. (2006) |

| WOM-intention about the firm | The customer's intention to conduct informal communications such as recommendations and evaluations of the firm | Zeithaml et al. (1996) |

Perceived value has been defined as the tradeoff between benefits and sacrifices (Sweeney & Soutar, 2001; El-Adly, 2019; de Kervenoael et al., 2019; Lin & Mattila, 2021). The literature has also identified different dimensions (utilitarian versus hedonic) that span multiple areas, such as human value, value chain, and entertainment value (Sánchez et al., 2006; El Adly, 2019; de Kervenoael et al., 2019). Perceived value is a relevant variable for an organisation because empirical studies have shown that it is a significant antecedent of repurchase intention, satisfaction, and loyalty (El Adly, 2019; de Kervenoael et al., 2019; Lin & Mattila, 2021).

FLEs are the main aspect of service firms’ value creation (Oderkerken-Schröder et al., 2021). Perceived FLE competence can positively influence firms’ perceived value (Ho et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2023). Wu et al. (2015) and Hoang and Tran (2022) establish a positive and significant influence of employee competence on service quality, a relevant component of the benefits associated with a firm's perceived value. Boninsegni et al. (2020) empirically test whether FLE friendliness significantly influences a firm's perceived value. Moreover, in the current state of CSR technology, some authors consider FLEs the key players in value creation (de Kervenoael et al., 2019; Ho et al., 2020). Lakshmi and Bahli (2020) consider that CSR may allow FLEs to focus on tasks that require creativity and high skills, improving firms’ perceived value. Therefore, FLE influences the perceived value of a firm through aspects, such as service quality, friendliness, creativity, and benefits, which allows us to state the first hypothesis.

H1

Customers-perceived competence in FLEs directly influences the perceived value of firms

Regarding the impact of CSR, studies that empirically tested the effect of satisfaction with HRI (error-free, need-fulfilling service encounters) on the perceived value of firms are scant (Belanche et al., 2020). Lin and Mattila (2021) consider that prior research has ignored the role of AI and robots in the value co-creation process. De Kervenoael et al. (2019) empirically demonstrate that a robot's perceived value is an important aspect of its intention to use a social robot, concluding that social robots provide a differentiated experience that supports creating sustainable value. Kang et al. (2023) conclude that the perceived creepiness and coolness of a service robot influence its perceived value in the hospitality industry. Lin et al. (2024) establish that perceived experiential value is a mediating variable between robot anthropomorphism and tourists’ co-creation behaviour. Therefore, CSR influences a firm's perceived value through various aspects such as differentiated experience, creepiness/coolness, anthropomorphism, and experiential value. Customer satisfaction with HRI increases the perceived value of the firm because the fulfilment of expectations generated by CSRs increases the benefits received from the firm.

H2

Customers’ satisfaction with HRI directly influences the perceived value of the firm

Regarding the relevance of causality, attribution theory states that CSRs have a higher degree of outcome stability. However, the current state of technology causes CSRs to complement FLEs in value co-creation, implying that customers consider FLEs primarily responsible for frontline services (de Kervenoael et al., 2019; Ho et al., 2020; Belanche et al., 2020). The FLEs are considered actors with higher variability in outcome stability than CSRs (Belanche et al., 2020). In this context, based on attribution theory, we hypothesise that customers attribute greater responsibility to FLE than to CSR when evaluating firms’ perceived value.

H3

Customers’ perceived value of a firm is influenced more by the perceived competence of FLEs than by satisfaction with HRI.

FLE, HRI, and intention of WOM about the firmCustomers commonly use WOM to share their opinions, communicate experiences, and advertise preferences (Sweeney et al., 2020; Taheri et al., 2021; Talwar et al., 2021). The development of ICT has transformed the behaviour of WOM by creating e-WOM through social networks, blogs, reviews, comments, shares, likes, and other forms of user engagement, facilitating the rapid and global dissemination of ideas, behavioural styles, and values (Boateng et al., 2016). People connect to widely dispersed locations, exchange information, and share new ideas and emotional states using social media (Fang et al., 2018). Digital networking provides a flexible means for creating diffusion structures, expanding membership, and extending them geographically. This impulse responds to human social motivation based on altruism, a sense of social duty, and the pleasure of recounting experiences (Keiningham et al., 2018). Thus, WOM can be activated because of service experience. The WOM is a significant outcome for firms, especially in the wake of social digitalisation and the importance of viral messages.

The literature has empirically tested the influence of FLE on WOM, particularly in failure situations (Nguyen et al., 2019; Correia & Ferreira, 2020; Moisio et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2024). If the FLE performs as expected, positive WOM is likely to be generated; however, if the FLE's competence is below expectations and a failure situation occurs, negative WOM may be generated (Keiningham et al., 2018; Talwar et al., 2021). Social networks and the Internet 5.0 favour the dissemination of WOM, especially in negative situations, which can become viral. Thus, we propose that a good perception of FLE competence generates positive WOM intention, and, in particular, a poor perception of FLE competence leads to negative WOM intention (Moliner et al., 2023).

H4

Customers’ perceived competence in FLEs directly influences their WOM intention about the firm.

Few studies relate the WOM intention of companies with CSR (Xu et al., 2023). Mariani and Borghi (2021) establish that the presence of text in online reviews of service robots positively influences e-WOM. In a real service context, the presence of a CSR is a novelty that generates a ‘Wow’ effect and has experiential value (de Kervenoael et al., 2019; Fuentes-Moraleda et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2024de Gauquier et al., 2023). The extraordinary nature of an interaction with CSR creates a memorable experience that is highly likely to be disseminated as positive WOM (Williams et al., 2020; Moliner et al., 2023). However, a failure generates customer dissatisfaction and provokes negative WOM intentions (Williams et al., 2020; Moliner et al., 2023). Thus, it can be hypothesised that CSR generates WOM intention: satisfactory HRI generates positive WOM intention, whereas unsatisfactory HRI leads to negative WOM intention.

H5

Customer satisfaction with HRI directly influences the WOM intention about a firm.

Attribution theory places greater responsibility on services with FLEs than CSRs. Thus, we hypothesise that the influence of FLE on WOM intention is significantly greater than that of CSR. However, the presence of CSRs elicits a ‘Wow’ effect (Fuentes-Moraleda et al., 2020) or novelty value (Lin & Mattila, 2021), which may be a powerful incentive for WOM intention (Fuentes-Moraleda et al., 2020). However, though the ‘Wow’ effect justifies the influence of HRI on WOM intention, the conceptual framework considers that FLEs are attributed more responsibility. Therefore, FLEs have a significantly greater effect on WOM intentions.

H6

Customers’ WOM intentions about the firm are more influenced by the perceived competence of FLEs than the satisfaction with HRI.

Moderating factorsAttribution theory posits that moderating factors are related to the conditions surrounding a service (Belanche et al., 2020). One of the most prominent differences between human-to-human interaction and HRI is the social–emotional capability of FLEs versus CSRs (Belanche et al., 2020). Although CSRs have some social–emotional capabilities, the state of the technology is still far from matching FLEs (Wirtz et al., 2018; Phillips et al., 2023). What happens in scenarios where CSRs have different social–emotional abilities? According to attribution theory, more responsibility is attributed to CSR with higher social–emotional ability (Belanche et al., 2020).

Notably, however, FLEs and CSRs form a team, and customers perceive the interdependence between them (Phillips et al., 2023; Khoa et al., 2023). Interdependence theory considers that a person's outcome depends on their and their partner's performance (Khoa et al., 2023). Currently, FLEs must support CSRs because FLEs mitigate rigid robot service delivery, complete comprehensive social–emotional tasks, and balance service robot constraints (Phillips et al., 2023). This is the so-called service robot–FLE task paradox, which reflects the additional work for FLEs when CSR is present (Phillips et al., 2023).

The front end of the service and how FLEs and CSRs perform their tasks and coordinate, intensify customers’ confidence in the company's competence to provide the service (Huang, 2012). Customer perception of the FLE–CSR team depends on social co-presence, the customer's feeling of being accompanied by a team composed of a human and a robot (van Doorn et al., 2017; Le et al., 2023). Conversely, it depends on explicit coordination, the communication between team members to articulate plans or seek information to carry out a task (Rico et al., 2019).

The FLE–CSR interdependence implies that a lack of social–emotional ability of one team member (CSR) leads to more responsibility being attributed to another member of the tandem (FLE). De Kervenoael et al. (2019) consider that an FLE's degree of empathy enables the generation of a differentiated value for the company; therefore, CSR empathy should be considered a central driver of HRI. Robots with superior empathic and social skills promote customer familiarity and affinity and increase emotional engagement with the firm (de Kervenoael et al., 2019).

Therefore, attribution theory considers that a CSR's lack of social–emotional ability causes responsibility to be attributed to an FLE in a co-creation 5.0 scenario (Belanche et al., 2020). The FLEs are usually perceived as responsible for the positive or negative performance of an FLE–CSR team (Swanson & Davis, 2003). However, it remains to be established whether differences in the CSR's social–emotional abilities affect this attribution of responsibility. We hypothesise that the higher the social–emotional ability of the CSR, the greater the responsibility attributed to it, and the lower the influence of the perceived competence of FLEs on the firms’ outcomes.

H7

The greater the social–emotional ability of CSR, the lower the attribution of responsibility to FLEs for the firms’ outcomes.

Fig. 1 graphically represents the relationship model and hypotheses.

MethodologyA questionnaire was designed using adapted scales validated in the literature (Table 3). This study received a favourable report from the University Ethics Committee (file number CD/109/2021), confirming compliance with the required ethical standards.

Measurement scales.

| Construct | Number of items | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived personnel competence | 4 | Khan and Rahman (2017) |

| Satisfaction with HRI | 3 | Kim (2018) |

| Perceived value of the hotel | 7 | de Kervenoael et al. (2019) |

| WOM intention about the hotel | 3 | Hwang, Park, and Kim (2020) |

The hospitality sector was selected because it suits customers’ interactions with FLE-CSR. Hotel lobbies are spaces with a high flow of customers, making it easy to place service robots to complement the hotel reception staff. An experiment was designed using two CSRs in two Spanish hotels. The two robots, Tokyo and Nairobi (Fig. 2), had robotic and female human appearances, respectively. Their function was to provide customers with information about their destinations. These robots were selected; Tokyo, in particular, had a higher social–emotional ability since it used AI to deduce the gender and mood of the individuals it interacted with (customers were shown a game that aided Tokyo in making these determinations). This social-emotional skill of Tokyo is based on observing the customer's facial expression and interaction through a quiz, which allows for more fluid interaction between the customer, FLE, and CSR. However, Nairobi does not perform any socio-emotional activity despite having an anthropomorphic appearance. The main characteristics of the robot are listed in Table 4.

The experiment involved installing two CSRs for one week each in the lobbies of two hotels of the same chain. Both hotels were four-star, although one was an urban hotel and the other a sun and beach hotel. These characteristics were appropriate for this study because they enabled robot and hotel type segmentation.

Both hotels provided their facilities for the experiment, and a research team member supported the CSRs and administered the questionnaire following the customer–CSR interactions. When a hotel guest was interested in CSR, the researcher explained the research objectives, including the informed consent clause regarding data privacy. Guests passing through the hotel lobby approached the CSR because of the novelty of their presence. At that point, the researcher invited them to interact with the CSR. In addition to data collection, a qualitative study was conducted in which the research team observed customer behaviour, interacted with them after they had completed the questionnaire, and conducted in-depth interviews with the employees.

The fieldwork was conducted between May and August 2022. The total sample size was 633, of which 52.2% were men and 87% were 19–59 years. Confirmatory factor analysis was used to analyse the data. EQS was used as the statistical program.

ResultsQualitative researchThe qualitative study focused on two target audiences: customers and employees. For customers, we used the observation technique (before and during interaction with the robot) and conducted an in-depth interview (after completing the questionnaire). Thirty customers were interviewed within a few minutes after completing the questionnaire. Differences in participant profiles were taken into account: in the Madrid hotel, participants were older and multinational (from the USA, Spain, Argentina, Chile, Brazil, Belgium, and Mexico), and in the Benicàssim hotel, they were Spanish families with children on vacation, and Europeans attending the music festival FIB Festival Internacional de Benicàssim. In general, customers had a fun time interacting with the CSR, and their experience with the robot was positive. The robots experienced several glitches in their daily operations, such as battery problems, system overheating, and other technical problems that required regular assistance from technicians. This indicates that the technology is far from autonomously operational. Observations allowed us to detect that customers were attracted by the sight of a robot in the hotel lobby but were initially reluctant to interact. This reluctance was especially noticeable among the elderly. However, children were attracted to the robots like magnets. Some customers were indifferent to the robot's presence. Tokyo was regarded as more beneficial than Nairobi regardless of Nairobi's greater appeal, although it produced some rejection in female and elderly profiles.

The second part of the qualitative study comprised in-depth interviews with hotel employees following interactions with robots. Interviewees numbered 25 (14 from the Madrid hotel and 11 from the Benicàssim hotel). The profile included ten men and 15 women: six aged between 19 and 30 years, 11 between 30 and 39 years, two between 40 and 49 years, and six between 50 and 59 years. Fifteen were receptionists, and ten had other functions. The main conclusion was that employees were reluctant regarding the presence of robots in hotel lobbies and interacting with them. Overall, they had a poor opinion of CSRs because they did not consider them useful or add value to the hotel. This poor opinion was especially relevant in the case of Nairobi. Employees felt that robots would not help improve customer experience, service efficiency, or standardise quality. In general, reception staff rated more negatively than other hotel employees. In contrast, the robots’ ease of use was rated highly. Some employees suggested that robots could wear the hotel uniform to increase their integration. Thus, as some studies indicate, the opinion of the employees, especially the FLEs with whom the robots teamed, was not significantly positive.

Convergent and discriminant analysis of the scales of measurementRegarding the quantitative study, in this comprehensive analysis, we first present the findings of a confirmatory factor analysis with structural equations, focusing on the latent variables and their respective indicators (Table 5). The model fit statistics indicate that the proposed structural equation model aligns well with the empirical data. The Chi-square (χ2) value is 67.6457, with 56 degrees of freedom (df) and a p-value of 0.13692. While the p-value slightly exceeds the conventional significance level of 0.05, the other fit indices are exceptionally robust. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) stands at a commendable 0.023, and both the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI) exhibit high values of 0.994 and 0.991, respectively. These indices collectively affirm the model's robust goodness of fit (Jöreskog & Sörbom,1996).

Confirmatory factor analysis.

| Latent variables (4)/Items | Factor loading | t-value | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived personnel competence | 0.72 | 0.89 | ||

| Helpful and kind | .82*** | 7.46 | ||

| Appearance is very good | .84*** | 9.83 | ||

| The service provided is excellent | .71*** | 12.64 | ||

| The care offered is very good | .92*** | 10.26 | ||

| Satisfaction with HRI | .89 | .96 | ||

| I am satisfied with the interaction and the service received | .93*** | 22.40 | ||

| My expectations have been met | .90*** | 25.49 | ||

| In general, I am satisfied with this robot | .99*** | 27.88 | ||

| Perceived hotel value | .78 | .90 | ||

| The quality–price ratio is good | .88*** | 9.99 | ||

| The difference between what I have paid and what I have received is positive | .86*** | 15.14 | ||

| During my stay all my needs and wants were satisfied | .87*** | 11.77 | ||

| WOM intention about the hotel | .91 | .97 | ||

| I will probably say positive things about this hotel to other people | .92*** | 14.67 | ||

| I would probably recommend this hotel | .98*** | 18.06 | ||

| It is likely that it will encourage others to visit this hotel | .95*** | 19.59 |

Note: the model fits Chi-square (χ2): 67.6457; df: 56; p: 0.13692; RMSEA: 0.023; CFI: 0.994; NNFI: 0.991

AVE is the average variance extracted; CR is the composite reliability.

Factor loadings reveal the strength of the associations between latent constructs and their observed indicators. Our analysis identified four latent constructs: ‘perceived personnel competence’, ‘satisfaction with HRI’, ‘perceived hotel value’, and ‘WOM intention about the hotel’. All indicator loadings significantly exceed the recommended threshold of 0.7, confirming that our indicators effectively encapsulate the intended latent constructs (Bagozzi, 1980; Bagozzi & Yi, 1988; Hair et al., 2006).

Average variance extracted (AVE) values gauge the proportion of variance explained by latent constructs in their indicators. A well-constructed model typically features AVE values of 0.5 or higher. In this analysis, all four constructs comfortably surpass this threshold, with AVE values of 0.72, 0.89, 0.78, and 0.91 for the respective constructs. This underscores the constructs’ explanatory power over their associated indicators (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Composite reliability (CR) measures the internal consistency of latent constructs. For reliable constructs, CR values should ideally exceed 0.7. In our study, all four constructs exhibit CR values exceeding this threshold, registering values of 0.89, 0.96, 0.90, and 0.97. This attests to the reliability and internal consistency of the latent constructs under investigation (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988).

To summarise, our confirmatory factor analysis results indicate that the proposed model is an excellent fit for the data. The latent constructs exhibited reliable and robust associations with their respective indicators. While the p-value for the chi-squared test is marginally above 0.05, the RMSEA, CFI, and NNFI values corroborated a compelling fit, underlining the validity of our model and the effectiveness of our chosen indicators in capturing the intended latent constructs.

This research underscores the appropriateness of the selected indicators for evaluating ‘perceived personnel competence’, ‘satisfaction with HRI’, ‘perceived hotel value’, and ‘hotel intention of WOM’. These findings enhance our understanding of these constructs and provide valuable insights into marketing research, particularly in the context of hotel service and customer satisfaction.

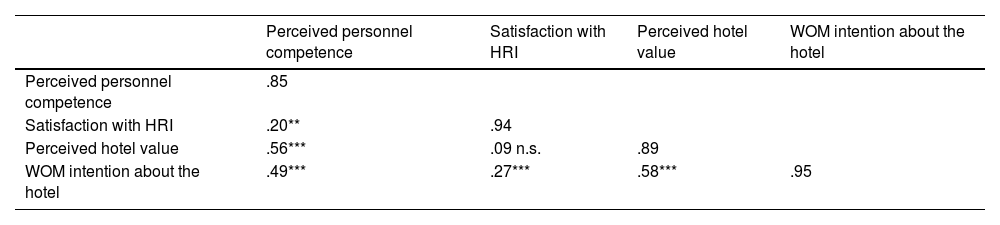

Table 6 displays discriminant validity, which plays a critical role in establishing that latent constructs (‘perceived personnel competence’, ‘satisfaction with HRI’, ‘perceived hotel value’, and ‘hotel intention of WOM’) truly represent distinct dimensions of the hotel experience. Notably, all the correlations between these constructs are consistently below 0.7. Importantly, these correlation values are lower than the diagonal values, corresponding to the square root of the AVE of each construct.

This key observation reaffirms the discriminant validity of the model. Essentially, it indicates that these latent constructs do not exhibit significant overlap. In simpler terms, each measures a unique and separate aspect of the hotel guest experience, and the correlations between them remain well below the 0.7 threshold. Regarding structural equation modelling, this outcome is highly desirable, as it underscores the model's ability to differentiate and capture the various facets studied effectively. This, in turn, strengthens the reliability and robustness of the model as it demonstrates that each construct measures something distinct from the others, thereby enriching our understanding of hotel guests’ experiences.

Causal model and moderator variablesOnce the measurement model was validated and the convergent and discriminant validity of the measurement scales confirmed, the causal model was tested. Table 7 shows the results and the fit indices. Perceived personnel competence is seen to influence perceived hotel value significantly (β=0.688; p<0.001) and hotel intention of WOM (β=0.562; p<0.001). Satisfaction with HRI significantly influences the hotel intention of WOM (β=0.143; p<0.001) but not perceived hotel value (β=0.018). Additionally, the influence of perceived personnel value on hotel intentions for WOM is greater than that of satisfaction with HRI. This implies that H1, H3, H4, H5, and H6 are satisfied, but not H2.

Linear regression.

| Perceived personnel value | Hotel intention of WOM | |

|---|---|---|

| Constant | 4.469*** | 3.908*** |

| Perceived personnel competence | 0.688*** | 0.562*** |

| Satisfaction with HRI | 0.018 | 0.143*** |

| Age | 0.012 | 0.144*** |

| Sex | −0.017 | 0.070*** |

| R2 adjusted | 0.479 | 0.425 |

| ANOVA Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| VIF≤ | 1.076 | 1.081 |

Significance: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

The control variables show biases according to age and sex: the older the participant, the higher the WOM intention about the hotel, and women also have a higher WOM intention.

Regarding the moderating effects of the FLE–CSR team, two variables were used for the analysis: a) the type of robot to determine whether the social–emotional ability of the robot influences the relationships between the base model variables and b) the hotel to determine whether the FLE–CSR teams of both hotels moderate the relationships in the base model.

Table 8 shows the moderating effects of the robot type. All variables included in this analysis were mean-centred before the calculation to avoid interference from multicollinearity. The results obtained indicate that robot type only has a moderating effect on the relationship between perceived personnel competence and perceived hotel value (β=0.194; p<0.001). There is no moderating effect on the other three causal relationships in the base model.

Moderating effects: type of robot.

| Perceived hotel value | Hotel intention of WOM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 4.456*** | 4.421*** | 3.349*** | 3.336*** |

| Perceived personnel competence | 0.774*** | 0.699*** | 0.580*** | 0.545*** |

| Satisfaction with HRI | 0.007 | 0.014 | 0.172*** | 0.174*** |

| Age | −0.003 | 0.010 | 0.147*** | 0.154*** |

| Sex | −0.019 | −0.015 | 0.068** | 0.069*** |

| Moderator effect | ||||

| Type of robot | −0.040 | −0.013 | 0.047* | 0.061* |

| Personnel competence × robot (Tokyo 1/Nairobi 2) | 0.194*** | 0.052 | ||

| Satisfaction HRI × robot (Tokyo 1/Nairobi 2) | 0.043 | 0.001 | ||

| R2 adjusted | 0.509 | 0.480 | 0.434 | 0.429 |

| ANOVA Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| VIF≤ | 1.486 | 1.474 | 1.466 | 1.449 |

Significance: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Furthermore, we conducted simple slope analyses to illustrate the moderating effects. As shown in Fig. 2, for the FLE–Nairobi team, the positive impact of perceived personnel competence on hotel perceived value (β=0.800; p<0.001) is higher than the impact of the FLE–Tokyo team (β=0.633; p<0.001) at the 0.001 level of significance. This implies that perceived personnel competence has a more pronounced positive effect on perceived hotel value in Nairobi than in Tokyo. Therefore, for a CSR with fewer social–emotional skills (Nairobi), more responsibility is assigned to personnel, which confirms H7.

An additional analysis was conducted to study the effect of the FLE–CSR team on firms’ outcomes. Table 9 shows that the hotel moderates the relationship between perceived personnel competence and perceived hotel value and the relationship between satisfaction with HRI and WOM intention about the hotel.

Moderating effects: Hotel.

| Perceived hotel value | WOM intention about the hotel | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 4.444*** | 4.459*** | 4.000*** | 4.003*** |

| Perceived personnel competence | 0.732*** | 0.695*** | 0.526*** | 0.516*** |

| Satisfaction with HRI | 0.011 | 0.014 | 0.172*** | 0.159*** |

| Age | 0.004 | 0.018 | 0.096*** | 0.106*** |

| Sex | −0.028 | −0.017 | 0.062** | 0.060** |

| Moderator effect | ||||

| Hotel | 0.031 | 0.017 | −0.127*** | −0.129*** |

| Personnel competence × Madrid team (1)/Benicàssim team (2) | −0.115*** | −0.052 | ||

| Satisfaction HRI × Madrid team (1)/Benicàssim team (2) | −0.001 | −0.058** | ||

| R2 adjusted | 0.490 | 0.478 | 0.440 | 0.440 |

| ANOVA Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| VIF≤ | 1.390 | 1.285 | 1.394 | 1.380 |

Significance: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

The simple slope analysis (Fig. 3) shows that in Madrid, the positive influence of perceived personnel competence on perceived hotel value (β=0.712; p<0.001) is significantly greater than in Benicàssim (β=0.647; p<0.001) at the 0.001 significance level. This suggests that personnel competence has a significantly higher positive impact on perceived hotel value in Madrid than in Benicàssim.

As for the other significant moderating effect, analysis indicates that in Madrid, the positive impact of satisfaction with HRI on hotel intention of WOM (β=0.271; p<0.001) is significantly higher than in Benicàssim (β=0.085; p<0.001) at the 0.01 significance level. This implies that satisfaction with HRI has a significantly higher positive effect on the hotel intention of WOM in Madrid than in Benicàssim.

Therefore, the influence of the FLE–CSR team on the perceived hotel value and intention of WOM is higher in the Madrid hotel than in the Benicàssim hotel, a responsibility attributable to both the FLE and CSR.

Therefore, the results of the moderating effects show that a) the worse the social–emotional skills of CSR, the more responsibility customers attribute to personnel, and b) customers attribute responsibility for the firm's outcomes to both actors in the FLE–CSR team. Table 10 summarises the degree of fulfilment of the hypotheses.

Hypotheses testing.

| Path | Result | |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Perceived personnel competence –> perceived hotel value | Supported |

| H2 | Satisfaction with HRI –> perceived hotel competence | Not supported |

| H3 | Perceived personnel competence has a greater influence on perceived hotel value than satisfaction with HRI | Supported |

| H4 | Perceived personnel competence –> WOM intention regarding the hotel | Supported |

| H5 | Satisfaction with HRI –> WOM intention about the hotel | Supported |

| H6 | Perceived personnel competence has a greater influence on WOM intention about the hotel than satisfaction with HRI | Supported |

| H7 | The greater the social–emotional ability of the CSR, the less attribution of responsibility to the FLE for the firm's outcomes | Supported |

This study examines the consequences of co-creation 5.0 on firms’ outcomes in a real context and analyses the moderating effect of the FLE–CSR team. The results show that both actors are responsible for firms’ outcomes, although FLEs are more accountable than CSRs.

Regarding RQ1, as hypothesised, the main antecedent is the FLE. The perceived competence of the FLE significantly influences the firm's perceived value and WOM intention about the firm more than satisfaction with HRI. This lower importance of CSR coincides with the results of Hoang and Tran (2022), who found that a human cleaner is perceived as more competent than a robot cleaner. It is noteworthy that satisfaction with HRI does not influence the perceived value of firms, which can be explained by the low relevance of the role played by CSRs (limited information distribution). These results confirm the conclusions of some authors that customers place more importance on FLEs than on CSRs when evaluating firms’ outcomes (Belanche et al., 2020; Oderkerken-Schröder et al., 2021; Phillips et al., 2023; Khoa et al., 2023).

Regarding RQ2, FLEs are primarily responsible for firms’ outcomes from a customer perspective. Customers regard CSRs as partners in the service delivery team, albeit with a complementary character, because they have no direct influence on firms’ perceived value and have a significantly lower impact than FLEs on WOM intention. Greater social–emotional and empathic skills of CSRs lead to increased attribution of responsibility by customers. However, the customer visualises a team consisting of an FLE and CSR and expects coordinated and satisfactory performance. A team with higher perceived competence achieves better outcomes for the firm (Khoa et al., 2023). Customers’ perceptions of FLE and CSR as a team affect the evaluation of the whole team and the firm's outcomes when the performance of one of the two agents drops. Personnel must compensate for CSR's social-emotional deficiencies to improve firms’ outcomes. This result confirms the CSR–FLE task paradox because the presence of a robot in co-creation 5.0 entails more work than benefits for personnel (Phillips et al., 2023). Given that the results show that CSR also contributes to improving a firm's outcomes and that its impact on co-creation 5.0 is significant, firms face the CSR–FLE task paradox.

Concerning RQ3 (What are the perceptions of customers and FLEs regarding augmented service?), this context of FLE–CSR interdependence and positive customer ratings of CSR contrasts with the FLE's negative view of the robot, identified in the qualitative study. Negative perceptions of FLE regarding CSR have been identified in other studies (Parvez et al., 2022a,b; Song et al., 2022a,b; Tu et al., 2023; Willems et al., 2023; Wong et al., 2023; Tojib et al., 2023). This is called the Tin–Woodman paradox. Like Tin Woodman looking for the Wizard of Oz to give him a heart, CSR requires social–emotional skills to integrate into a co-creation 5.0 environment and be accepted by the partner. However, the FLE considers that CSR does not help improve customer satisfaction, service efficiency, or quality standardisation. The CSR may require acceptance by FLEs, but FLEs reject it for fear of losing their jobs. The FLEs are unaware of the interdependence between the two players from the customers’ perspective nor of the benefits that collaboration could bring to their work, including avoiding repetitive tasks and focusing on highly skilled tasks. The Tin–Woodman paradox is a valid problem for firms because accepting CSRs is the key to augmented services (Phillips et al., 2023).

ConclusionsTheoretical contributionsThe first contribution of this study is that it tests the relevance of both actors in co-creation 5.0. So far, no 360° analysis of customer and FLE perceptions has been conducted. The integration of both perceptions has made it possible to identify the Tin Woodman paradox, which is a major challenge for the service industry and co-creation 5.0 since the positive reception of augmented services by customers contrasts with the negative view of FLEs. This paradox clarifies the complexity of the relationships among FLE, CSR, and customers (Belanche et al., 2020; Paluch et al., 2022; Song et al., 2022a,b; Le et al., 2023).

The second contribution is customers’ vision of FLE–CSR as a team. Noble et al. (2022) posit the research question of which combination of tasks makes service collaboration more (less) effective and enjoyable for human actors (customers and employees). This study sheds light on this issue. The social–emotional skills of the robot influence the FLE-CSR team performance because the lower the social–emotional abilities of the CSR, the greater the responsibility attributed to personnel competence. These results can be interpreted as the greater the CSR's social–emotional skills, the more responsibility the customer attributes to it in generating the firm's outcomes. These results show FLE–CSR interdependence, an effect not yet tested in the literature.

Practical implicationsIn addition to the current state of CSR technology, which still does not guarantee satisfactory co-creation 5.0, the main problem of the FLE–CSR team is the Tin Woodman paradox. Phillips et al. (2023) proposed that CSRs should be integrated into services using an augmentation–substitution strategy. They can be substituted by FLEs in some simple tasks, despite many tasks, especially the social–emotional ones, that require an augmented role for FLEs. Firms should consider the CSR–FLE task paradox, given that placing CSRs in a real service context entails additional work for FLEs, which affects their well-being (Lu et al., 2020; Phillips et al., 2023). Notwithstanding this paradox, firms should evaluate the advisability of incorporating CSRs with some social–emotional skills to moderate the effects of employee misconduct on firms’ outcomes.

Along with the FLE–CSR task paradox, the literature has detected other negative impacts on employee well-being following the introduction of service robots in service delivery (Lu et al., 2020; Phillips et al., 2023; AlQershi et al., 2023). AlQershi et al. (2023) suggested that FLEs may feel threatened or at risk of losing their jobs in the presence of CSRs. This may demotivate talented workers, resulting in the subsequent loss of valuable knowledge associated with such employees and damaging the firm's value proposition. Firms must address the threats that employees perceive by identifying the benefits in augmented service situations. Khoa et al. (2023) considered that hospitality management should work on three areas to ease FLEs’ acceptance of this disruptive technology: train FLEs for the new scenario, establish ethical governance for cobotics, and build FLEs’ trust in CSRs.

Lakshmi and Bahli (2020) considered that the new collaborative scenario poses challenges, such as paying attention to unintended situations and the consequences of the robot's behaviour. Similarly, overconfidence in a robot's capabilities can result in inefficiency and ineffectiveness. Therefore, the big challenge for organisations is for FLEs to treat CSRs as peers (Noble et al., 2022).

It follows that service 5.0 is not a neutral decision. In the real service context, CSR influences customer perceptions and firms’ outcomes. Hotels must plan and prepare a service schedule so that FLEs can support CSRs and customers interact with both actors seamlessly. The FLEs cannot disengage from CSRs because customers regard both agents as interdependent. Hotels must also consider that incorporating a robot with more developed social–emotional skills will consequently increase their responsibility towards the service, which may have a positive or negative impact on firms’ outcomes.

Social impactThere is a widespread societal view that CSRs will replace FLEs in many jobs. This impression has been reinforced by the emergence of several AI tools that bring the social–emotional capabilities of CSRs and humans closer together (Kraus et al., 2023). Given that no one can foresee its scope or impact, concern about the consequences of AI on society persists. Several authoritative voices have warned about the risk of not regulating AI.

As in all industrial revolutions, the most redundant and repetitive tasks will be automated, resulting in the replacement of employees; nonetheless, with growth in services, and the creation of new positions (Lakshmi & Bahli, 2020). The fifth industrial revolution focused on human technology and well-being, implying that the social impact of technology on sustainable development goals (SDGs) must be investigated (Noble et al., 2022). Following the SDGs, substitutions affecting the most vulnerable, less-skilled groups who perform more repetitive tasks must be contemplated. In addition, in co-creation 5.0, employee and customer well-being could be compromised. Therefore, disruptive innovations that affect the digitisation and automation of many jobs must also be analysed from the perspective of social impact, as they can generate pockets of vulnerable workers replaceable by machines.

Limitations and future agendaThe main limitation is the type of robot used. A broad CSR typology eists with different levels of AI and social–emotional capacities. It would be beneficial to replicate this study with other CSRs. Another limitation is the setting chosen for conducting the experiments, which included two hotels from the same chain. The existing hotel typology is extensive, and it would be convenient to replicate this study in other establishments. The third limitation relates to the cultural context. The customers interviewed were from Western countries, which limits the extrapolation of the conclusions to different cultures, such as Asian, Arab, and African countries.

This study opens new avenues for future research. An interesting line would be to delve into FLE–CSR interdependence in service 5.0 and the impact of the Tin Woodman paradox. Although CSRs’ social-emotional skills appear to influence the attribution of responsibilities, other moderating variables may exist, such as the importance of the task performed by CSRs or the technological skills of the customer. Further investigations of different CSR categories, environments, and cultural settings are required to corroborate these results on a broader scale.

FundingThis work was supported by the State Research Agency (STR) of the Ministry of Science and Innovation of the Spain Government supported this study (Grant number: I+D+i MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/PID2020-115585RB-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/)

CRediT authorship contribution statementMiguel A. Moliner-Tena: Writing – original draft, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Luis J. Callarisa-Fiol: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition. Javier Sánchez-García: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Rosa M. Rodríguez-Artola: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization.

Literature review of co-creation 5.0.

| Reference | Topic of FLE-robot team (dependent variable) | Theoretic framework | Methodology of empirical study | Robot role | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leung et al. (2020) | FLEs' intention to use service robots | Technology affordance theory and socio-material perspective | Lab experiments | Augmenting FLE | Hotel employees prefer a room service robot with physical affordance to a concierge robot with cognitive affordance because the room service robot offers more relative advantages and higher trust. |

| De Gauquier et al. (2023) | Shopper behaviour when interacting with FLE-robot team | POS conversion funnel | Survey with videos | Replacing and augmenting FLE | Service robot was the best option to generate attention and stop passers-by; however, the least number of passers-by were lured into the store. The FLE initiated the lowest number of interactions but could convert the highest number of passers-by into actual buyers. The FLE-robot team encouraged the highest number of passers-by to look at the store but did not convert most of them compared to the robot on its own. |

| Tu et al. (2023) | FLE willingness to work with service robots | Theory of Planned Behaviour | Survey | Augmenting FLE | The effects of employees' technology readiness, negative attitudes towards robots, and Big Five personality on intention to work with robots are inconclusive. |

| Wu et al. (2023) | Consumers' willingness to pay more | Service-Dominant Logic | Lab experiments | Replacing FLE | In-person coproduction settings, low-innovativeness consumers are willing to pay more to coproduce with human employees. In contrast, high-innovativeness consumers are willing to pay more to coproduce with robots. |

| Willems et al. (2023) | FLE's expected impact on job characteristics, job engagement and well-being | Employee well-being | Survey | Augmenting FLE | Retail FLEs expect that working with service robots can alleviate certain job demands; however, robots cannot help to replenish their job resources. Most retail FLEs expect the pains and gains associated with robots to cancel each other out. |

| Wong et al. (2023) | Customer's acceptance of AI | The artificial intelligence device usage acceptance and cognitive appraisal theory | Survey | Augmenting and replacing FLE | Employee presence moderated customers’ acceptance of AI. Human staff is still critical even in smart service encounters, especially when customers are looking for superior performance with low effort when using AI devices. |

| Tojib et al. (2023) | How anthropomorphic service robots with different levels of intelligence affect FLE. | Anthropomorphism | Experiments in consumer panel | Augmenting and replacing FLE | The effect of service robot anthropomorphism on employees' morale is mediated by perceived job-security threat and the type of AI. |

| Le et al. (2023) | FLE-robot collaboration | Interdependence theory | Conceptual | Augmenting FLE | It defines three structural components of the FLE-robot interdependence relationship: common goal, shared workflow and joint decision-making authority. |

| Holthöwer and van Doorn, (2023) | Customer discomfort | Social presence | Lab experiments | Replacing FLE | Consumers feel less judged by a robot (vs. a human) when engaging in an embarrassing service encounter, and prefer being served by a robot instead of a human. Robot anthromorphism moderates the effect. |

| Parvez et al. (2022a) | Employees' intention to use robots and collaboration | Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) | Survey | Augmenting FLE | Robot's perceived usefulness and ease of use positively influence employees' behavioural intentions to use robots and human-robot collaboration. The advantages and disadvantages of robots have a positive impact on robot awareness. |

| Parvez et al. (2022b) | Service employees' perception of service robots | Hospitality 5.0 perspective | Survey | Replacing FLE | Employees' awareness of adopting and using service robots significantly impacts their perception of robot-induced unemployment. The perception of robots' social skills significantly influences service employees' perception of robot-induced unemployment. |

| Song et al. (2022a) | The impacts of employees' perceptions on employee-robot collaboration | Sense-Think-Act framework | Survey | Augmenting FLE | Perceived risk and playfulness are the key drivers of employees' effort and performance expectancy, and perceived risk has the strongest positive impact on effort expectancy. |

| Paluch et al. (2022) | FLEs perception of collaborative service robots | Appraisal theory | Qualitative interviews | Augmenting FLE | It presents four employee personas (supporter, embracer, resister and saboteur) that help to understand how FLE-robot collaboration may differ |

| Lin and Mattila (2021) | Robotic-human partnerships | Collaborative intelligence and TAM | Qualitative+Survey | Augmenting FLE | Perceived privacy, functional benefits of service robots, and robot appearance positively influence consumers' attitudes towards adopting service robots. Functional benefits and novelty impact consumers' anticipated overall experience. |

| Song et al. (2022b) | Customers' perceived authenticity | Product level theory and authenticity | Survey | Augmenting FLE | Using robots at the core and facilitating product levels is less effective in improving consumers' perceived service and brand authenticity. |

| Belanche et al. (2020) | Attribution of responsibility | Attribution theory | Survey | Augmenting FLE | Customers make stronger attributions of responsibility for the service performance towards humans than robots, specifically when a failure occurs. The perceived performance stability is greater when the service is conducted by a robot than by an employee. |

| Ivanov et al. (2020) | Managers' perceptions of service robots | Supply-side perspective | Survey | Augmenting and replacing FLE | Repetitive, dirty, dull and dangerous hotel tasks would be more appropriate for robots. Managers prefer using employees for tasks requiring social skills and emotional intelligence. The managers considered that robots would decrease the quality of the service and were generally not ready to use robots. |

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.