Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and technological innovation (TI) are two fundamental driving forces for sustainable development. The importance of the CSR-TI relationship has grown in prominence over recent years. This study is motivated by two research questions: (1) What makes the CSR-TI relationship conclusions different? (2) Which emerging themes in the literature will likely set the stage for future work? Using VOSviewer for co-occurrence analysis, this research examines 67 scholarly works in related research fields from 1996 to 2023 in 36 leading journals to answer these questions. This paper is a systematic literature review of the CSR-TI relationship from different perspectives. Addressing these two research questions helps us clarify the internal logic of the existing research in the CSR-TI relationship, deepens the understanding of the relationship between CSR and TI, and provides a glimpse of the future.

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and technological innovation (TI) are two key driving forces for sustainable development (Bocquet et al., 2017; Dey et al., 2020; Shin et al., 2022), and thus, the importance of the CSR-TI relationship has been accentuated in recent years. Many companies incorporate CSR behaviors in their TI, committing themselves to spur responsibility through technological innovation and efforts. Hence, they deploy the innovative technological capabilities for CSR purposes. Over the last 28 years, various empirical studies on the CSR-TI nexus have been published in response to the call for strengthening economic and social development through technological advances. The conclusions and insights drawn from these studies have provided valuable insights into specific aspects of the field, and most of these papers have provided useful insights for mapping the influence of CSR on TI (Garel & Petit-Romec, 2021; Rodgers et al., 2013; Vishwanathan et al., 2020). Yet, extant research has fallen short of underscoring the variety of different assessments of the field.

Existing literature on the CSR-TI topic mainly focuses on the following three aspects: (1) the explorations of the linear effect of CSR on TI (e.g., Boehe & Barin Cruz 2010; Shin et al. 2022; Vishwanathan et al. 2020; von Weltzien Høivik & Shankar 2011); (2) the argument of the curvilinear effect of CSR on TI (Broadstock et al., 2020); and (3) the investigation of CSR on TI in different market environments (Hu et al., 2022; Ramus et al., 2018; Ren et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2022).

Yet, despite the growing importance of the CSR-TI relationship, several important theoretical issues remain within this field. For instance, there may be two different effects between CSR and TI, namely the “promotion effect” (Boehe & Barin, 2010; Garel & Petit-Romec, 2021; Mishra, 2017; von Weltzien Høivik & Shankar, 2011) and the “crowding out effect” (Miles et al., 2002; Mithani, 2016; Murcia, 2021). The promotion effect may occur when an increase in CSR activities simultaneously stimulates TI. On the other hand, the crowding out effect argues that under the call of “innovation” and “sustainable development,” companies’ pursuit of competitive advantages in both CSR and TI has triggered their competition for limited internal resources. As a result, managers are caught in a dilemma of allocating scarce resources between CSR practices and TI. To make matters worse, the findings of the different effects of CSR and TI are contradictory. Actually, the existing research fails to provide more nuanced insights on how different CSR purposes impact TI and narrowly focuses on issues to drive the field forward. Taking these limitations as a starting point, the current study analyzes the most recent research published in 36 leading journals from 1996 to 2023. This inquiry is motivated by two research questions:

- (1)

What makes the conclusions on the CSR-TI relationship divergent?

- (2)

Which emerging themes in the literature will likely set the stage for future work?

Gaining such insights is vital in light of the inconsistent findings of the literature examining the CSR-TI relationship. Our paper makes three significant contributions in this regard. First, we develop a comprehensive and interdisciplinary review of the literature on the CSR-TI relationship over the last 28 years and situate our analysis within the broader management literature. Second, based on this review, we identify key themes and insights and the differentiating attributes of this body of CSR-TI scholarship as a distinctive field within the management literature. Third, we consolidate the main distinctive themes, identify lingering gaps, and provide relevant guidance for future research.

We begin with the method of the review, detailing sampling and analysis of the literature. Next, the theoretical approaches section provides insights into the main theories employed by extant literature. Afterward, we review relevant literature that sheds light on the relationship between CSR and TI. Finally, the discussion and conclusions sections overview the essential findings and outline three promising avenues for future research.

MethodsSampleThe main aim of this paper is to summarize the relationship between CSR and TI, the underlying mechanism(s) explaining the effect, and the boundary condition(s) for the relationship. Consequently, the systematic literature review (SLR) approach was adopted to explore the literature linking CSR and TI (Centobelli et al., 2020, 2021; Shashi et al., 2020). The systematic literature review approach has many advantages over other generic literature review approaches, such as synthesizing the literature systematically, transparently, and for replication (Kushwah et al., 2019; Tranfield et al., 2003). At the same time, SLR is conducive to reducing the bias and chance effect, thus enhancing the legitimacy of research methods and conclusions (Reim et al., 2015). Due to the inherent benefits of the SLR approach in rationality and legitimacy, numerous studies have used it (Kushwah et al., 2019; Risi et al., 2023; Schaltegger et al., 2022). Although different studies present different specific ideas in using the SLR approach, these studies share three common steps. They start with the planning of the review (Inclusion and exclusion criteria), proceed with the execution of the review (Journal selection, Databases, and Review protocol and outcomes), and end by reporting the results of the review (Data analysis and synthesis). Following the research of Tranfield et al. (2003), the SLR approach of this paper follows a similar three-step procedure.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaBased on the two research questions mentioned in the introduction, the inclusion and exclusion criteria of sample articles selection in this paper are as follows:

- (1)

Inclusion criteria. The SLR uses four inclusion criteria:

- (a)

Studies that focus on the relationship between CSR and TI;

- (b)

Studies published in the English language;

- (c)

Studies published in peer-reviewed journal articles;

- (d)

Studies whose title, abstract, keywords, and introduction focus on the relationship between CSR and TI.

- (a)

- (2)

Exclusion criteria. The SLR uses three exclusion criteria:

- (a)

Studies that do not focus on the CSR-TI relationship;

- (b)

Conference papers were ignored;

- (c)

Duplicate studies were excluded.

- (a)

To ensure consistency between the scope of the selected journals and the research questions, as well as to ensure the quality of the articles included in this literature review, this research refers to the ten top management academic journals based on the research of Montiel and Delgado-Ceballos (2014): Academy of Management Journal, Academy of Management Review, Administrative Science Quarterly, Organization Science, Journal of Management, Management Science, Journal of International Business Studies, Journal of Management Studies, Organization Studies, and British Journal of Management. All of these journals were included in Bansal and Gao's (2006) list, which was based on Cohen's (2006) list of the highest-quality journals. In addition, since CSR and technological innovation are closely related to organizational behavior and corporate strategy, we selected four journals on organizational behavior referring to the research of Montiel and Delado-Ceballos (2014): Journal of Applied Psychology, Personnel Psychology, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, and Journal of Organizational Behavior; and one strategy journal: Strategic Management Journal. Furthermore, in order to observe the relationship between CSR and TI in management practice, we selected four top practitioner management journals in the Fortune Magazine list (Montiel & Delgado-Ceballos, 2014): Harvard Business Review, Academy of Management Perspectives, California Management Review, and MIT Sloan Management Review. Finally, in order to enhance the representativeness of research conclusions as much as possible, this paper added eight journals based on the 20 high-impact journals proposed by Aguinis and Glavas (2012): Business & Society, Business Ethics Quarterly, International Journal of Management Reviews, Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, Journal of Marketing, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, and Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science; and nine general management journals (including strategy and organizational studies) and CSR journals with Academic Journal Guide (AJG) ratings are all above three stars (Risi et al., 2023): Global Strategy Journal, Group & Organization Management, Journal of Business Research, Journal of Management Inquiry, Leadership Quarterly, Long Range Planning, Organization, Research in the Sociology of Organizations, and Strategic Organization. All 36 journals have an impact factor above 3, with the lowest being three and the highest being 18.2, which shows that these journals have a high influence (Maon et al., 2019).

Table 1 provides a list of journals and the number of analyzed papers.

Number of papers per journal.

| Journal | Number of papers |

|---|---|

| Academy of Management Journal | 0 |

| Academy of Management Perspectives | 0 |

| Academy of Management Review | 0 |

| Administrative Science Quarterly | 0 |

| British Journal of Management | 2 |

| Business & Society | 5 |

| Business Ethics Quarterly | 2 |

| California Management Review | 0 |

| Global Strategy Journal | 1 |

| Group & Organization Management | 0 |

| Harvard Business Review | 0 |

| International Journal of Management Reviews | 0 |

| Journal of Applied Psychology | 0 |

| Journal of Business Ethics | 29 |

| Journal of Business Research | 12 |

| Journal of Innovation & Knowledge | 2 |

| Journal of International Business Studies | 0 |

| Journal of Management | 0 |

| Journal of Management Inquiry | 0 |

| Journal of Management Studies | 2 |

| Journal of Marketing | 0 |

| Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology | 0 |

| Journal of Organizational Behavior | 0 |

| Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science | 5 |

| Leadership Quarterly | 0 |

| Long Range Planning | 3 |

| Management Science | 0 |

| MIT Sloan Management Review | 0 |

| Organization | 1 |

| Organization Science | 0 |

| Organization Studies | 0 |

| Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes | 0 |

| Personnel Psychology | 0 |

| Research in the Sociology of Organizations | 0 |

| Strategic Management Journal | 3 |

| Strategic Organization | 0 |

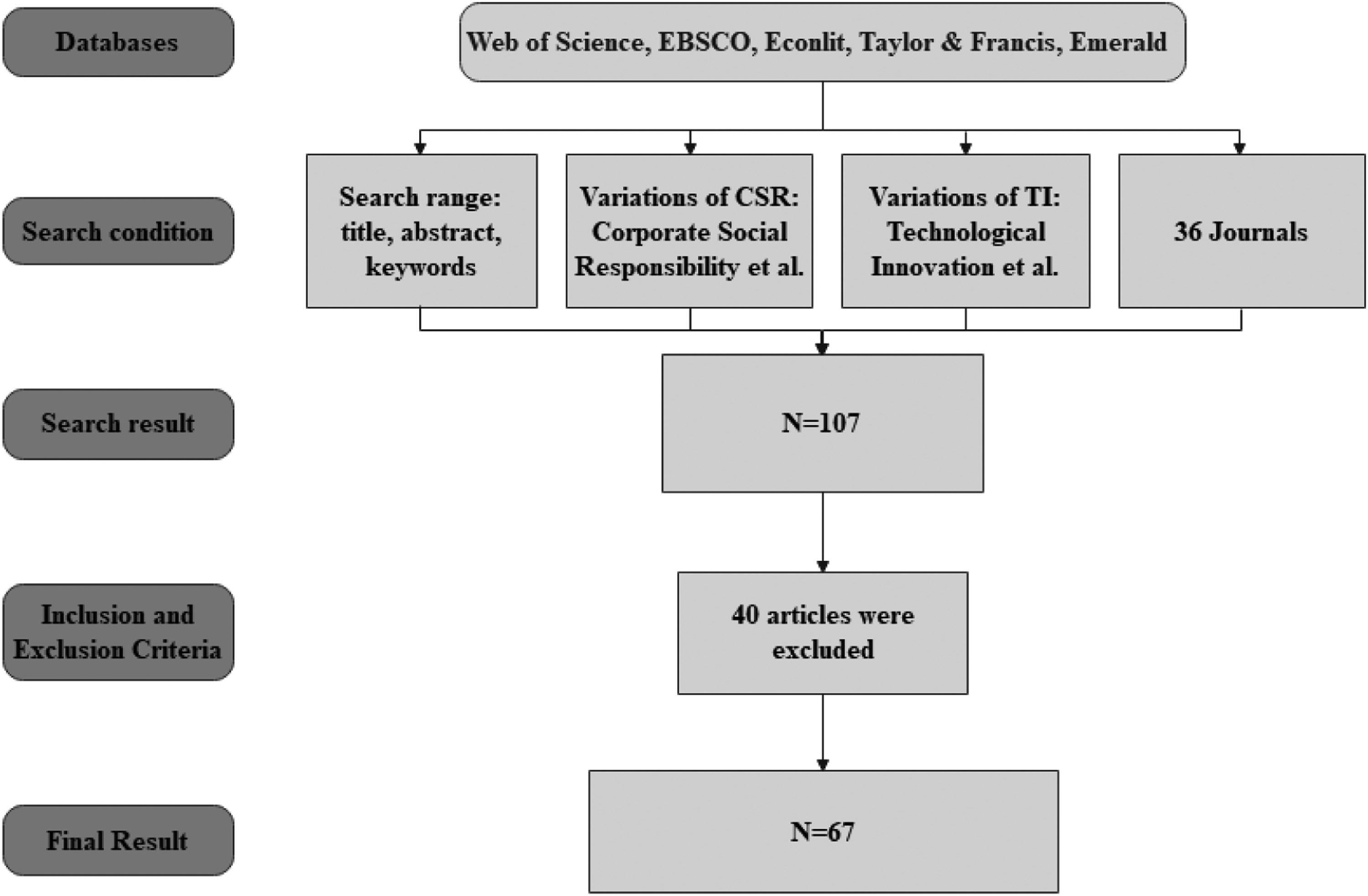

To improve the comprehensiveness and representativeness of the sample articles, the following five commonly used databases are used in this paper based on existing studies (Kushwah et al., 2019; Risi et al., 2023; Schaltegger et al., 2022). These databases are Web of Science, EBSCO, Econlit, Taylor & Francis, and Emerald since different databases can lead to different publications (Schaltegger et al., 2022).

Review protocol and outcomesConsidering that few studies contain both CSR and TI in the title, we ticked the “Search in title, abstract, and keywords” across all the five abovementioned databases (Schaltegger et al., 2022). The search terms used in this article are variations and derivatives of the CSR and TI concepts. Search terms related to CSR include “Corporate Social Responsibility,” “CSR,” “Corporate Responsibility,” “CR,” “Social Responsibility,” and “Corporate Citizen*,” and search terms related to TI include “Technology Innovation,” “Technological Innovation,” “TI,” “Innovation,” “Product Innovation,” “Process Innovation,” and “Technical Innovation” (Jamali & Karam, 2018; Schaltegger et al., 2022). The SLR started with the Web of Science database, and then the remaining four databases were individually searched to avoid duplicate articles. After the “title,” “abstract,” and “keyword” search in five databases with search terms, 107 non-duplicate articles were obtained. We evaluated these articles using the inclusion and exclusion criteria to retain 67 papers. To comprehensively observe the existing research, we did not set the beginning year of the SLR but proceeded inductively. The retrieval results suggest that the first topical paper was first published in 1996. Thus, the publication time interval of this review is 1996–2023. The article selection process is shown in Fig. 1.

Data abstraction and synthesisTo extract data related to the research questions, the coders of this paper conducted a detailed examination and review of the 67 articles obtained in the literature retrieval. Three coders trained in SLR methodology coded each article according to the following:

- (1)

The relationship between CSR-TI is positive, negative, or nonlinear;

- (2)

The theory employed;

- (3)

The research method is qualitative or quantitative (i.e., empirical);

- (4)

The country in which the study was conducted;

- (5)

The mediating and moderating variables involved in the CSR-TI relationship.

Three coders coded each publication independently and settled conflicts through discussion under the supervision of a fourth researcher. In addition, the fourth researcher reviewed the coding results, and the final coding results were given based on the consensus. The final coding results provide the research methods, theoretical framework, countries of research objects, and research variables of sixty-seven articles. This coding process enabled us to summarize the literature on the CSR-TI relationship and promote further research in this field.

AnalysisPublication timelineAs shown in Fig. 2, the 67 sample articles were published between 1996 and 2023 since the earliest sample article was published in 1996. The title of this first paper is How and why participatory management improves a company's social performance. This paper used the case study method to find that management innovation can improve social performance. In addition, the trend line shows that from 1996 to 2023, research on the CSR-TI relationship is on the rise, which indicates that this relationship and its defining effects will remain a meaningful and important topic in the future.

Journal distribution of sample articlesThe sample article number of each journal is shown in Table 1. The 36 journals with high Impact Factors include, among others, the Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, British Journal of Management, Business & Society, Business Ethics Quarterly, Global Strategy Journal, Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Business Research, Journal of Management Studies, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Long Range Planning, Organization, and Strategic Management Journal. These journals have all published research on the CSR-TI relationship. Among them, Journal of Business Ethics and Journal of Business Research have been published in large quantities, consistent with the article search results of Risi et al. (2023).

Geographic scopeThe geographic scope of the selected studies is presented in Fig. 3. Of the 67 articles, 45 identified the research subject's country, and 22 did not. We can see from Fig. 3 that most studies on the CSR-TI relationship were conducted in the United States (n = 13) and China (n = 7).

Keywords co-occurrence analysisOur review focused on 275 keywords in the selected 67 articles and used VOSviewer for co-occurrence analysis. VOSviewer is a helpful tool for co-occurrence analysis. It can clearly and efficiently show commonalities between articles and is widely used in research (Strielkowski et al., 2022; van der Weert et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023). A co-word network diagram is drawn based on the review of these articles. As shown in Fig. 4, the 67 articles mainly focus on the fields of “corporate responsibility,” “green innovation,” “competitiveness,” “sustainability,” “sustainable development,” “resource,” and “stakeholder.” We can preliminarily summarize variables included in the CSR-TI relationship from the keywords co-occurrence analysis.

Research methodsPrevious studies have used different methods to test the CSR-TI relationship, the action mechanism, and the boundary conditions in this relationship. To summarize the research methods used in the 67 sample articles, the SLR in this paper divided the research methods into qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods according to existing studies (McLeod et al., 2016). The coding results show that, out of the 67 articles, 26 use qualitative methods, 41 use quantitative methods, and none use mixed methods. In addition, there is also a gap in how the sample articles use qualitative and quantitative research methods. Qualitative research methods used in sample articles include case studies and literature reviews. Quantitative research methods used in sample articles include surveys, meta-analyses, and panel data analysis. Moreover, data processing methods include the multiple regression technique and structural equation modeling. The research methods of each article are shown in Appendix A.

TheoriesThe relationship between CSR and TI, the mediating variables, the moderating variables, and the theories used in the sample articles are shown in Appendix A. It can be seen that 58 articles study the impact of CSR on TI, and nine explore the effect of TI on CSR (the papers with gray shading in the column of the “CSR-TI relationship” are the articles studying the influence of TI on CSR).

Several powerful comparative frameworks discussing the CSR-TI relationship have been advanced in recent years. Stakeholder theory was the most widely employed theory (21 articles), followed by resource-based theory (RBT) (16 articles) and institutional theory (eight articles). Other noteworthy perspectives were ecological modernization, agency, corporate citizenship, social network, and strategic management theories. Due to the lack of coherent viewpoints on the CSR-TI relationship, the current study has adopted three prevailing theories- namely stakeholder theory, the resource-based view (RBV), and institutional theory- as a theoretical lens for much of our empirical work.

Under the aegis of stakeholder theory, the social responsibility of firms should satisfy the needs of different stakeholders, thus acquiring resources from them to implement TI (Du et al., 2010; Miles et al., 2002; Mirvis et al., 2016; Mishra, 2017; Murcia, 2021; Rodgers et al., 2013; Scandelius & Cohen, 2016). For instance, the responsibility of creditors helps firms have enough capital to conduct TI. The assumption of social responsibility to the government allows firms to get policy support to promote TI practice. Focusing on the needs of consumer markets and constantly updating the firm's products are also conducive to TI. While satisfying different stakeholders, heterogeneity in CSR, namely CSRs with different motives and natures, makes a difference in influencing TI (Shin et al., 2022; Waldron et al., 2022). Therefore, the stakeholder theory is employed to explain that the heterogeneity in CSR behaviors is one factor that makes the conclusions on the CSR-TI relationship divergent (Research Question 1). It is important to note that this discussion, based on stakeholder theory, sets a stage to further explore the relationship between different dimensions of CSR and TI (Research Question 2).

RBV signifies that fulfilling CSR and TI will consume many of the firm's resources. Since a firm's resources are limited, the firm is caught in a dilemma of allocating the resources needed for socially responsible practices and/or innovation activities (Hull & Rothenberg, 2008; Miles et al., 2002; Murcia, 2021). Due to the “promotion effect” and the “crowding out effect” between CSR and TI, RBV is applied in this study to categorize the influences on TI: the positive influence of CSR on TI, the negative influence of CSR on TI and the curvilinear effect of CSR on TI. Thus, RBV is utilized to mainly examine Research Question 1 (i.e., What makes the conclusions on the CSR-TI relationship divergent?)

Institutional theory signifies that the CSR-TI relationship is not the same in different institutional environments (Henderson, 2007). The institutional “rules of the game” like macroeconomic policies, economic systems, industrial environments, cultural traditions, and development levels may influence firms’ behavior (Marano & Kostova, 2016; Pache & Santos, 2010; Scherer et al., 2013). Based on the institutional theory, contingency factors of the relationship between CSR and TI are discussed. We believe the institutional theory is useful to analyze why the CSR-TI relationship is divergent while considering different context-specific factors (Research Question 1). The CSR-TI relationship needs further review since the Western CSR model may not be adaptable in emerging economies. Thus, the institutional theory also helps to shed light on the emerging issue related to future work (Research Question 2).

Based on these theoretical perspectives, the analysis reveals different types of relationships between CSR and TI. These include the positive influence of CSR on TI, the negative effect of CSR on TI, a curvilinear relationship between CSR and TI, a relationship between CSR and TI that is moderated by other factors (mainly personality-, company-, and institution-specific factors), and a relationship between CSR and TI that is mediated by other variables (particularly social capital and workforce).

ResultsThe positive influence of CSR on TIFrom the perspective of company strategy, the better the social responsibility is fulfilled, the more the demands of multiple stakeholders are taken into account, the more harmonious the corporate-stakeholders relationship, and the better the image and the social status of the company (Mishra, 2017; Rodgers et al., 2013). Thus, companies are more successful if they keep mutually-beneficial relations based on trust with the stakeholders who will provide resources such as capital, knowledge, information, and government support for TI (Shin et al., 2022; Waldron et al., 2022). Furthermore, CSR directly affects the individuals who invest in the company, therefore creating a cycle of benefits for the companies and the community (Chowdhury, Sarasvathy, & Freeman, 2023). In this sense, better CSR engagement helps companies attract higher-quality investors, gain more financial support, obtain superior business benefits, have more faithful customers, and tend to be more profitable. As a result, companies are more likely to conduct TI activities to reap those specific benefits.

The negative influence of CSR on TIThe trade-off hypothesis holds that a company's resources are limited. Therefore, the more a company fulfills its CSR, the fewer resources will be used in TI activities. As a result, a company's focus will be shifted from improving product quality and promoting TI to social relationship maintenance (Miles et al., 2002; Mithani, 2016; Murcia, 2021). Fulfilling CSR will inevitably consume vast funds and resources not allocated to technology investment (Hull & Rothenberg, 2008).

In developing countries, many valuable public resources, including land, state-owned assets, financial subsidies, and government credit, are in the hands of governments at different levels, which are more potent in allocating resources. As such, the more political resources a company has, the more likely the firm's performance is improved through rent-seeking rather than TI activities (Kiefer et al., 2017; Zimmerling et al., 2017). Politically-motivated CEOs engage in external CSR activities in order to establish good connections with the government and other key external stakeholders (Du et al., 2010). In addition, to obtain preferential policies, such as market access, tax incentives, and government subsidies, the companies are likely to engage in excessive CSR activities to get government trust. Accordingly, a considerable amount of resources are spent on these external CSR activities, reducing input in TI (Miles et al., 2002; Murcia, 2021).

The curvilinear effect of CSR on TIBased on the curvilinear effect of CSR on TI, some studies try to recognize there may be some synergy between CSR and TI. They put forward and verified the inverted U-shaped relationship between CSR and TI (Broadstock et al., 2020). These studies argue that CSR is not always conducive to TI, or they posit that CSR and TI do not always conflict sufficiently to constitute a zero-sum game between them. Therefore, the best value of CSR has to be investigated and kept within a reasonable range to avoid the negative impact of excessive CSR and maximize its incentive effect (Costa et al., 2015). When CSR is below a certain level, the TI of a company will be promoted accordingly with the increase of CSR intensity. If CSR intensity exceeds a certain level, however, the companies will fall into complex interactive relations with stakeholders, and various demands of multiple stakeholders must be considered, thus increasing the company's cost and reducing the efficiency of TI activities. Ultimately, it will lead to insufficient investment in TI resources (Broadstock et al., 2020).

Having discussed the linear and curvilinear effect of CSR on TI, we now highlight context-specific factors pertaining to managers-companies-institutions, which either amplify or dampen the effectiveness of a company's CSR efforts on TI.

Moderators of the CSR-TI relationship: personality-specific factorsAccording to the upper echelons theory, the personal traits of top executives affect strategic choices. Researchers in management have shown that top executives’ characteristics affect organizational decisions and behaviors (Chatterjee & Hambrick, 2007; Hambrick, 2007; Hambrick & Mason, 1984; Reger, 1997; Sanders, 2001). Liu et al. (2020) argue that there is a positive correlation between the personal traits of managers and CSR fulfillment since pursuing CSR activities is a means through which CEOs enhance their image and esteem. In fact, some narcissistic CEOs are more engaged in charity and donation to enhance their feelings of moral superiority and attract attention and praise (Petrenko et al., 2016). They are eager to receive respect from stakeholders, and thus, they will positively affect CSR fulfillment (Yang et al., 2021). Therefore, CEOs’ traits, such as narcissism, may promote CSR fulfillment and positively moderate the impact of CSR on TI.

Moderators of the CSR-TI relationship: company-specific factorsThis sub-section deals with three factors discussed in the CSR-TI relationship literature: organizational-level innovation practices, organizational inertia, and public visibility.

Organizational-level innovation practicesSome theoretical frameworks propose that organizational innovation practices enhance the positive impact of CSR on the generation of TI outcomes (Anzola-Román et al., 2023; Boulouta & Pitelis, 2014; Broadstock et al., 2020). The impact of CSR on TI is conditioned by the orchestrated efforts of different operational and specialized units within the company (Bendell & Nesij Huvaj, 2020). The practices related to organizational innovation, such as decentralization in decision-making, changes in production methods, or learning practices, help firms achieve TI that matches specific CSR objectives (García-Marco et al., 2020). For example, innovative practices related to changes in production organization (e.g., autonomous or semiautonomous teams and quality circles), as well as labor organization (e.g., job rotation, increased worker responsibility) are fundamental resources to sustain and direct absorptive capacity and thus impact companies’ TI performance (Antonelli & Scellato, 2013). Furthermore, innovative practices such as learning practices can strategically reinforce how employees enact and share their knowledge (Gangi et al., 2019; González-Masip et al., 2019) and become a crucial moderator for the effect of CSR on TI. Thus, implementing internal companies' innovation practices is needed to seek the positive effect of social CSR on TI performance.

Organizational inertiaOrganizational inertia refers to the tendency to maintain established organizational behavior and habits. It is divided into resource rigidity (i.e., the failure to change resource investment patterns) and routine rigidity (i.e., the inability to change organizational processes that use those resources) (Gilbert, 2005). The process of using CSR to acquire and use external knowledge to influence the company's TI performance inevitably involves adjusting the company's relevant routines. Thus, the routine rigidity in organizational inertia moderates the effect of CSR on the company's TI performance (Jiang et al., 2020). On the other hand, when the routine is more rigid, the difficulties encountered by the companies in facing the diverse demands of external stakeholders will involve the company's restructuring, and the efficiency of the companies’ TI will be more negatively affected (Murcia, 2021).

Public visibilityPublic visibility reflects how the general public observes companies’ actions regarding their business operation and management (Ren et al., 2023). Public visibility is a pre-condition for stakeholders to respond to companies’ behaviors. The recent literature indicates that public visibility generally correlates with stakeholders’ positive responses (Pollock et al., 2008; Rindova et al., 2005). Because visible companies draw more attention, public visibility also helps stakeholders to judge whether companies’ CSR activities meet their expectations (Amores-Salvadó et al., 2014). Companies with high public visibility can better build, maintain, or enhance relationships with multiple regulatory stakeholders, making it easier for them to access financial capital and preferential political support (Husted & Allen, 2007b), thus facilitating CSR translates into TI outcomes.

Moderators of the CSR-TI relationship: institution-specific factorsSome characteristics of institutional factors moderate the effectiveness of the CSR-TI relationship. This section discusses three institution-specific factors: competition intensity, market uncertainty, and informal institutions.

Competition intensityCompetition intensity means the degree of competition that firms face in a given industry. Some researchers have sought to find a link between CSR, competition intensity, and TI. However, the findings have not reached a consensus.

Some studies argue that market competition intensity plays a negative moderating role in the CSR-TI relationship. When competition intensifies, the firm faces increased demands from external stakeholders (Ren et al., 2023). The fierce market competition implies more challenges from competitors. Such challenges are reflected in discovering new market TI opportunities to enhance TI efficiency. When a company's excessive CSR activities lead to its intricate relationships with external stakeholders, it becomes more challenging to identify and respond quickly to new market innovation opportunities (Hu et al., 2022). Thus, competition intensity negatively moderates the CSR-TI relationship. However, some scholars have argued when the competition is fierce, companies are more inclined to retain and attract high-quality talents for TI activities through positive social responsibility behaviors (Rubera & Kirca, 2017). As such, market competition positively moderates the positive influence of CSR on TI.

Market uncertaintyIn an informal and uncertain market, the rules for market competition remain less predictable and blurry than in most formal and advanced economies because the formal institutions that support free markets, such as adequate legal infrastructure, are still evolving (Hoskisson et al., 2000). Therefore, companies must acquire resources from external stakeholders in a timely manner to carry out TI activities in order to improve their survival and adaptability (Achi et al., 2022; Hu et al., 2022). As a tool to help obtain access to scarce resources and information beneficial to TI from external stakeholders, CSR is more likely to be favored by companies (Lin et al., 2015; Park et al., 2017). In addition, the higher the degree of market uncertainty, the more unstable the relationship between the company and its external stakeholders (Wang et al., 2022). As a result, external stakeholders are less motivated to pressure the company to cater to their interests. Companies are less likely to be embedded in complicated networks with external stakeholders (Rubera & Kirca, 2017). Ultimately, market uncertainty positively moderates the influence of CSR on TI.

Informal institutionsUnlike formal institutions, informal sanctions mainly rely on values, ethics, cultural traditions, customs, and ideology (Fehr & Williams, 2018). Informal sanctions play a crucial role in enforcing social norms and providing public goods (Hu et al., 2022; Ren et al., 2023). Informal institutions such as moral norms and public opinion modify, supplement, or expand formal institutions, thus influencing resource allocation and company behavior in economic operation. Focusing on the moderating effect of informal institutions, some studies introduce the culture of internal responsibility (Chen et al., 2023; Jiang et al., 2020; Ramus et al., 2018) and the external social reputation of companies (Axjonow et al., 2018; Gwebu et al., 2018; Lin-Hi & Blumberg, 2018) into the relationship between CSR and TI. They reveal the normative guiding functions of informal institutions (such as corporate culture and information transmission) and expectation constraint functions (such as corporate social reputation) to verify the different moderating effects of informal institutions on the CSR-TI relationship.

Mediators of the CSR-TI relationshipSome research explored the mediating mechanisms that account for the effectiveness (or ineffectiveness) of the impact of CSR on TI. This section elaborates on two factors from external and internal perspectives.

Social capitalBased on the “CSR-external social capital-TI” pattern, the external perspective holds that social capital enables companies to establish good relations with stakeholders such as shareholders, employees, consumers, and suppliers through external social networks before obtaining information and resources (Mirvis et al., 2016; Scandelius & Cohen, 2016). Hillebrand et al. (2015) point out that the current market environment has shown a networking trend. The exchange and sharing of adequate information and scarce resources will promote the formation of a stakeholder network. The stakeholder network in which a company is embedded dramatically affects its ability to adapt to the environment, utilize resources, and gain a competitive advantage. By actively fulfilling social responsibilities, companies will be driven to establish social capital, obtain diversified information and resources from various stakeholders, and carry out TI (Maxfield, 2008; Mirvis et al., 2016; Scandelius & Cohen, 2016).

WorkforceThe internal perspective argues that mobilizing the initiative of internal employees of an organization is a source of TI. Through CSR, companies might translate human resource constraints into business benefits (Bocquet et al., 2013). It can help them recruit attractive employees by broadening the talent pool due to greater gender and nationality diversity (Gudmundson & Hartenian, 2000). Moreover, by increasing the diversity of their workforce, companies may enhance their adaptive capacity to compete in international markets (Loane et al., 2007), and the breadth of perspectives available to diversity, if adequately aligned with CSR, may thus improve decision quality and encourage innovation (Bocquet et al., 2017; Ueki et al., 2016). Companies engaged in CSR may benefit from different opportunities and, therefore, may exploit the value of workforce diversity. That is, a company with CSR is likely conscious of value-in-diversity. Because a company engages in CSR, it voluntarily pursues diversity, enhancing its performance, especially TI.

DiscussionThe following discussion provides an overview of the key findings. The discussion is organized along the two research questions underlying the study.

What makes the conclusions on the CSR-TI relationship divergent? (Research question 1)While many worthwhile studies discuss the relationship between CSR and TI, their results are sometimes contradictory. This study explores the various reasons concerning the conflicting results between CSR and TI. Past research indicates that possible reasons for the contradictory findings may stem from the heterogeneity of CSR and the heterogeneity of TI, as well as the spatial and temporal issues between CSR and TI, which may be solved in the future.

First, there is heterogeneity in CSR. CSR behaviors are divided into mandatory, responsive, strategic, and altruistic CSR behavior according to the willingness to fulfill (as illustrated in Table 2). From the motive perspective, companies’ mandatory and responsive CSR are passive behaviors, while strategic and altruistic CSR is dynamic. Specifically, compulsory CSR is when a company fulfills its responsibilities passively to avoid legal punishment and social condemnation. Responsive CSR is a company's behavior to fulfill CSR to cater to the public and to the government. Companies follow the mantra of “satisfying whoever has needs,” aiming at promoting short-term development rather than implementing firm strategy and long-term development. Strategic CSR is a company's behavior combining CSR fulfillment with the firm strategy. When fulfilling CSR, a company will consider all stakeholders to strengthen relationships with them. Based on stakeholder theory, Gallo et al. (2004) divide strategic CSR into internal and external CSR. Internal CSR emphasizes providing satisfactory products and services for society, creating economic wealth, and ensuring the company's sustainable development. At the same time, external CSR is intended to correct the damage caused to society by economic activities. Altruistic CSR is the highest level for companies to fulfill CSR. At this stage, the company will integrate itself with society and regard CSR as a dedication to repay society instead of seeking returns.

Classification and main characteristics of CSR.

| Behavioral Classification | Main characteristics | Attitude of companies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude towards CSR | Motive for fulfilling CSR | Influence on organization goals | |||

| Mandatory CSR behaviors | No action-passive acceptance. Forced to fulfill social responsibilities according to government policies and moral pressure imposed by the public. | Abide by laws, regulations, and social morality to avoid legal sanctions and moral condemnation. | Improve the company's legitimacy: reduce the negative impact caused by failing to fulfill essential responsibilities. | No actionPassive acceptance | |

| Responsive CSR behaviors | Passive acceptance-self-adaptation. Consider CSR as a tool to enhance the corporate image and use CSR to cater to the public and the government. | Enhance the corporate image and gain the favor of the public and the government. | Promote short-term development: The corporate image can be improved, and the short-term behavior of the company is consistent with the requirements of the public and society. | Self-adaptation | |

| Strategic CSR behaviors | Internal CSR (Maintain internal relations within the company) | Self-adaptation-Active Intervention. Combine CSR with internal stakeholder maintenance strategy to form a unique cooperative relationship. | Maintain the relationship with internal stakeholders and form a good cooperation atmosphere to improve the production efficiency of the organization. | Promote sustainable development: The company maintains harmonious relationships with the stakeholders, the organization's efficiency is improved, and the external financing constraints are reduced, all of which will help the firm occupy the market. | Active intervention |

| External CSR (Maintain external relations of the firm) | Self-adaptation-Active Intervention. Combine CSR with external stakeholder maintenance strategy to form a unique cooperative relationship. | Maintain the relationships with external stakeholders, reduce the external financing constraint, and expand the market. | |||

| Altruistic CSR behaviors | Active intervention-Full acceptance. In addition to fulfilling mandatory CSR, the firm actively and voluntarily undertakes social responsibilities not required by the political system and ethics. | Seek the realization of firm value. Show corporate culture and ideology, contribute to society, and give back to society. | Realize the harmonious development of the firm and society. Integrating the firm with society actively fulfills responsibilities and benefits society. | Full acceptance | |

Source: summarization based on extant research.

According to the heterogeneity of CSR, different CSR types with various motives and natures have divergent levels of influence on TI. Meanwhile, most existing literature uses rough CSR variable measures that are unclear, too generic, and lacking any comparative studies. This makes the suggestions on companies’ implementation of CSR and TI not pertinent.

Second, there is heterogeneity in TI. The existing studies on the influencing mechanism of CSR on TI also ignore the heterogeneity of TI. TI calls for introducing or developing new elements like new ideas, new products, new processes, new sources of raw materials, or new production methods (Hayward, 1998). Table 3 shows the definitions and features of different types of TI. TI is divided into different types according to various standards based on the differences in types, purposes, or ways the new elements are produced. TI is divided into product innovation, craftsmanship, and management innovation from the perspective of the object of innovation. From the innovation level perspective, TI comes in two types: exploratory and exploitative innovation. TI is divided into capital-saving, labor-saving, and neutral innovation from the perspective of resource-saving. From the perspective of organizational form, TI is divided into independent, joint, and imported innovation. Due to the differences in the learning path, R&D investment, resource allocation, and strategic objectives of the heterogeneous TI, the influencing mechanisms of CSR on them may differ.

Classification, definition, and characteristics of TI types.

| Division basis | Name of TI | Definition | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Object of TI | Product innovation | Product innovation refers to TI activities that produce new products, including tangible products and services. | Production of new products (tangible products or services) |

| Process innovation | Also known as process innovation. Craftsmanship innovation refers to the TI activities in which the technological process and manufacturing technology are improved or changed in the production procedures of firms. | Innovation in the production process | |

| Management innovation | Management innovation refers to TI activities that improve or produce new organizational management models. | Innovation in management models | |

| Level of TI (based on the dual innovation theory) | Exploitative TI | Exploitative TI is a small-scale, gradual, and innovative behavior that continues the established technology track, aiming to improve the quality of existing products, reduce energy consumption, and expand product categories to enhance the current market performance. | Low risk, low uncertainty, and low R&D investment |

| Exploratory TI | Exploratory TI is a large-scale, radical, and innovative behavior that breaks away from the existing technology track, aiming to develop new products, processes, and services in potentially competitive fields in the future. | High risk, high uncertainty, and high R&D investment | |

| TI aimed at resource-saving | Capital saving innovation | Capital saving innovation refers to TI activities that reduce capital input and improve output in product production; TI methods produce higher output with the same capital input. | Reduce capital input and increase output |

| Labor-saving innovation | Labor-saving innovation refers to TI activities that reduce labor input and improve output in product production; TI methods produce higher output with the same labor input. | Reduce labor input and increase output | |

| Resource-saving neutral innovation | Resource-saving neutral innovation refers to the TI activities that simultaneously reduce labor and capital input and improve output in product production; TI methods produce higher output with the same capital and labor input. There is no particular emphasis on saving capital or labor. | Reduce the input of capital and labor at the same time and increase the output | |

| TI aimed at creating new organizational forms | Independent innovation | Independent innovation refers to the TI activities developed and completed by a firm's in-house technical personnel and departments. | Easy to coordinate and control, and the firm has to be powerful. |

| Joint innovation | Joint innovation refers to the TI activities developed and completed by a firm with external organizations (other firms, the government, and institutions). | The coordination, management, and control are complicated but may fully play multi-organizations' advantages and improve innovation efficiency. | |

| Imported innovation | Imported innovation refers to the TI activities in which a firm directly introduces the innovation achievements of other organizations instead of carrying out innovation activities on its own. | Fast, low-risk, high initial capital investment. |

Source: summarization based on extant research.

Third, the relationship between CSR and TI is spatial and temporal. When discussing the direct relationship between CSR and TI, the existing studies argue that the relationship is a one-way causality, ignoring the influence of some vital contingent factors and the possibility of dynamic interaction (Benabou & Tirole, 2004). For example, the positive impact of conducting CSR activities on TI capability does not happen overnight but requires a gradual process with a certain lag. On the one hand, from the perspective of spatial dimension, different countries have different contexts for study. The CSR-TI relationship is not the same in different institutional environments (Henderson, 2007). In developing countries, markets are inefficient, and market prices do not adequately reflect all known information. Many irrational factors will interfere with the stakeholders when they receive information. It may be difficult for the stakeholders in these markets to obtain timely and comprehensive information about the fulfillment of companies’ CSR. The approach to CSR in Western countries has neglected these developments and works on the assumption of intact national institutions and a strict separation of public and private realms (Kitzmueller & Shimshack, 2012; Mäkinen & Kourula, 2012; Sundaram & Inkpen, 2004).

On the other hand, from the temporal point of view, to win the trust and support of stakeholders through active CSR, companies need to go through a process from the disclosure of CSR information, the transmission of CSR information to final acceptance by stakeholders (Zahra & George, 2002). In addition, companies have to experience a series of stages such as identification, evaluation, digestion, and application to build a knowledge base, absorb new knowledge, and cultivate new abilities (Pavlou & El Sawy, 2011). Therefore, CSR has a lag effect on the promotion of the TI capability of firms. Thus, addressing this research question provides us with a complete understanding of the progress made to date in the field of CSR-TI relationships.

Which emerging themes in the literature will likely set the stage for future work? (Research question 2)Based on the analysis of the extant research results, this paper develops three promising but under-investigated research agendas for future research on the CSR-TI relationship.

- (1)

Regarding the influencing mechanism of heterogeneous CSR on TI, most of the extant research distinguishes different kinds of CSR based on traditional classification, namely mandatory CSR, responsive CSR, strategic CSR, and altruistic CSR. This classification fails to acknowledge the real purpose of CSR. CSR with different objectives has a varying influence on companies' choices. While several excellent studies based on this theory discuss the relationship between CSR and innovation, attempts to deconstruct CSR purposes are not common. We must continue to flesh out how different CSR purposes influence a company's TI. The objectives of CSR are likely to be more complicated in emerging countries such as China. In order to build fame, some companies in China prefer to invest resources in CSR activities that can build and strengthen their reputation. They are eager for external attention and recognition and hope that the CSR they fulfill will bring them more significant social popularity, media praise, and an excellent social image (Campbell, 2007; McCarthy et al., 2017; Petrenko et al., 2016). Under the current conditions of the imperfect rule of law and insufficient penalties for fraud behaviors in China, companies may focus more on “pseudo-CSR behaviors” and neglect the investment in TI. For instance, the existing research shows government regulating authorities enforce the laws and regulations on the environmental strategies of the firms; while the public media, an effective carrier of the information of the firms to the outside, expose behaviors that damage the environment to the public (Mao & Wang, 2019). To avoid the punishment of the government and pressures from the news media and to enhance the image of the firm in the eyes of the public, the organizations are reevaluating their manufacturing processes in response to pressures concerned with the eco-friendly well-being of the stakeholders (Kiefer et al., 2017; Zimmerling et al., 2017).

Future studies should also investigate further CSR purposes: doing well or doing good? Doing well and good for whom (Maon et al., 2019)? The purposes of CSR need to be recontextualized via text analysis, questionnaires, or other tools to better observe the relationship between different dimensions of CSR and TI. Such research can improve our understanding of the inconsistency underlying the impact of CSR on TI and, therefore, have rich implications in this field. Policies on the implementation of CSR by firms will not be well-targeted without precise deconstruction of CSR purposes and comparative research. For this endeavor, future research can further explore whether different definitions of CSR impact TI differently.

- (1)

Further studies are needed on the particular institutional factors of CSR influencing TI. The existing empirical studies on the CSR-TI relationship touch on this issue by discussing various context-specific factors but are far from enough. The institutional environment is a very delicate matter (Marano & Kostova, 2016; Pache & Santos, 2010; Scherer et al., 2013). In particular, informal institutions are deeply ingrained in some emerging economies (Li et al., 2008). Thus, it is unsurprising that some informal elements, namely, culture, values, or links with the government, provide pervasive means to influence the CSR-TI relationship. Due to the differences in macroeconomic policies, economic systems, industrial environments, cultural traditions, and development levels, the rationality of the Western CSR model and the local adaptability of the study conclusions still need to be further reviewed. For example, in China, where CSR awareness has not yet emerged, there are significant differences between the perceptions and reactions of companies to CSR and those of companies in developed countries. In such a setting, does the problem of excessive CSR fulfillment of firms in Western countries exist in China? Do firms in China more frequently face the dilemma of insufficient CSR? In the future, the context of the study should be extended to various other developed and developing countries for comparison purposes. The unique attributes of CSR in emerging countries, in particular, warrant deeper exploration in order to better promote TI and enrich the theoretical research in this field.

- (2)

Exploring how TI impacts CSR is one important avenue for future research. There is relatively little research (nine out of 67 papers reviewed) on the impact of TI on CSR in emerging or developed economies. Only the papers of Chen et al. (2023), Collins (1996), Cruz, Boehe, and Ogasavara (2015), Dey et al. (2020), Huarng et al. (2021), Husted et al. (2015), Mishra (2017), Yuan et al. (2020), and Duan et al. (2022) deal with this issue. Seven of these nine papers conducted empirical research on the TI-specific factors that affect the charitable donations of firms. They found that firms with higher R&D investment intensity will make more charitable donations. They consider CSR a driver of company innovation activities and believe that companies that fulfill CSR need to adopt TI in their production processes and products to improve resource efficiency and reduce environmental pollution. Besides, they believe that companies’ TI will help them to fulfill CSR. However, the existing literature on this issue, primarily based on developed economies, tends to flow from a set of known, institutional “rules of the game.” The influence of TI on CSR needs further discussion, and the basic proposition that ‘institutions matter’ should be debated. Future research can take this as a starting point to provide various initial answers to these relevant but largely unresolved questions to push the research frontier.

Although theoretical development has brought CSR and TI ever closer, the relationship has not yet been unequivocally verified through studies. Our literature review comprehensively examined the research on the relationship between CSR and TI. After the analyses, we summarized the following conclusive remarks, as indicated in Fig. 5.

- (1)

To identify the CSR-TI relationship addressed in the leading academic journals, the systematic literature review evaluated the selected 67 studies on various parameters, such as publishing timeline, theories, dependent variables, moderators and control variables adopted, research methods, and geographic scope of the publications. The research on the CSR-TI relationship is immensely rich, but it has not been adequately explored yet. Furthermore, the review suggests the number of studies on the CSR-TI relationship fluctuated in the past decades. Still, the trend line shows that the number of related pieces of research was rising, indicating a growing interest in this field globally.

- (2)

Through integrating various perspectives, the current study examines the linear and curvilinear impact of CSR on the performance of TI, providing an opportunity to assess the field of the CSR-TI relationship in terms of its foundational theories, its research method types, and conclusions.

- (3)

The moderating effects on the relationship between CSR and TI are clarified based on context-specific factors pertaining to managers, firms, and institutions, deepening the understanding of contingency factors of the relationship between CSR and TI.

- (4)

From the internal and external perspectives of the company, the mediating effects of the relationship between CSR and TI are explored, deepening the understanding of the mediating mechanisms underlying the impact of CSR on TI. This additional layer of explanation (i.e., presence of mediators) has rich implications for company strategy.

- (5)

Given the limited focus on issues to drive the field forward, the current study responds to this call by identifying specific research questions that can be addressed to move the CSR-TI relationship agenda forward, which is essential to generate new knowledge. The future research directions will act as a platform for charting further investigations.

Accordingly, our review makes two distinct contributions to the literature. First, theoretically, this paper takes CSR with different content as the mainline and organically combines TI and its influencing factors. It helps expand the perspectives of CSR research and also provides theoretical guidance for the sustainable development of companies.

Second, practically, this paper examines the relationship between CSR and TI from different perspectives. As such, it helps companies establish the goal and directions of TI, accurately analyzes and identifies social needs, and documents the directions, guidelines, and plans for boosting TI value. As a result, the companies will form strategies that may regulate their behavior, promote competition, protect stakeholders’ interests, and enable sustainable and coordinated development of companies and society.

Although the present study provides an overview of the current status and prospects for scholarly research in the CSR-TI link, several limitations exist in the current systematic review. First, the SLR process is mainly qualitative; thus, coders may make subjective evaluations and judgments, potentially adding bias to the coding results. Therefore, future studies can use quantitative research methods like meta-analysis to review the literature. Secondly, we limited the study to 36 leading journals to ensure the high quality of sample articles. However, it is worth mentioning that many valuable articles on the CSR-TI relationship were also published in other journals that were not included in the current research. Therefore, future studies should consist of as many journals as possible to review the relevant literature comprehensively. Lastly, dissemination of scholarly work in the CSR-TI relationship is not limited to refereed journals. Books and monographs also serve this purpose. Therefore, future systematic review approaches to explore the CSR-TI relationship should consider books, book chapters, monographs, and potentially even other relevant research formats.

CRediT authorship contribution statementHailan Yang: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Resources. Xiangjiao Shi: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology. Muhammad Yaseen Bhutto: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Resources. Myriam Ertz: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Resources.

| Study | Authors (Year) | Theory | Research type | CSR-TI relationship | Mediating variable | Moderating variable |

| Paper 1 | Mishra (2017) | resource-based view | quantitative (panel data; n=3004; multiple regression) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 2 | Bocquet et al., 2017 | evolutionary perspective; strategic management theory | quantitative (panel data; n=213; multiple regression) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 3 | Kushwah et al. (2019) | marketing theory | qualitative (literature review) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 4 | Rodgers et al. (2013) | stakeholder theory; resource-based view | quantitative (panel data; n=497; multiple regression) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 5 | Isaksson et al. (2010) | stakeholder theory | qualitative | positive | – | – |

| Paper 6 | Yuan et al. (2020) | business strategy theory; resource-based view | quantitative (panel data; n=13,999; multiple regression) | positive | – | Social capital |

| Paper 7 | Boulouta and Pitelis(2014) | resource-based view | quantitative (panel data; n=104; multiple regression) | positive | – | Organizational-level innovation practices |

| Paper 8 | Chen et al. (2023) | signaling theory | quantitative (panel data; n=2862; multiple regression) | positive | – | state-owned or not |

| Paper 9 | Murcia (2021) | organizational hypocrisy theory | quantitative (panel data; n=122; multiple regression) | positive and negative | – | vertically integrated;absorptive capacity |

| Paper 10 | Garel and Petit-Romec (2021) | stakeholder theory | quantitative (panel data; n=2612; multiple regression) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 11 | Hoivik and Shankar (2011) | – | qualitative (case study) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 12 | Boehe and Cruz (2010) | resource-based and institutional theory | quantitative (survey; n=252; structural equations modeling) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 13 | Wagner (2010) | knowledge-based view | quantitative (panel data; n=3697; multiple regression) | positive | – | family firm |

| Paper 14 | Miles et al. (2002) | – | qualitative | negative | – | – |

| Paper 15 | Zhang (2010) | stakeholder theory | quantitative (panel data; n=103; multiple regression) | positive | customer orientation | – |

| Paper 16 | Waldron et al. (2022) | activist-driven responsible innovation theory; stakeholder theory | qualitative (case study) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 17 | Vishwanathan et al. (2020) | – | quantitative (n=344; meta-analytic structural equation modeling) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 18 | Flammer et al. (2019) | agency theory | quantitative (panel data; n=4533; multiple regression) | positive | CEO behavior | – |

| Paper 19 | Vakili and Zhang (2018) | creative class theory | quantitative (panel data; n=4533; multiple regression) | positive | innovation team diversity; knowledge sharing | – |

| Paper 20 | Flammer and Kacperczyk (2019) | resource-based view | quantitative (panel data; n=30,216; multiple regression) | positive | Knowledge leakage | – |

| Paper 21 | Ren et al. (2023) | institutional theory | quantitative (panel data; n=183; multiple regression) | positive | – | environmental enforcement intensity; state-owned; media coverage |

| Paper 22 | Dey et al. (2020) | complementarity theory | quantitative (survey; n=199; multiple regression) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 23 | Husted et al. (2015) | resource-dependency theory; the resource-based view | quantitative (survey; n=110; multiple regression) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 24 | Shin et al. (2022) | institutional theory | qualitative (survey) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 25 | Cruz et al. (2015) | resource-based view | quantitative (panel data; n=195; multiple regression) | positive | product-level CSR | – |

| Paper 26 | Arora and Kazmi (2012) | corporate citizenship theory | qualitative (case study) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 27 | McDermott et al. (2013) | social network theory | qualitative | positive | social capital | – |

| Paper 28 | Wang et al. (2022) | stakeholder theory; contingency theory | quantitative (panel data; n=226; multiple regression) | positive | – | market turbulence; technological turbulence |

| Paper 29 | Ueki et al. (2016) | resource-based theory | quantitative (survey; n=200; multiple regression) | positive | employee skills; workforce | – |

| Paper 30 | Broadstock et al. (2020) | stakeholder theory | quantitative (panel data; n=320; multiple regression) | nonlinear | – | Organizational-level innovation practices |

| Paper 31 | Achi et al. (2022) | resource-based theory | quantitative (panel data; n=176; multiple regression) | positive | – | environmental volatility |

| Paper 32 | Upadhaya et al. (2018) | stakeholder theory; resource-based view | quantitative (survey; n=132; structural equations modeling) | positive | organizational culture | – |

| Paper 33 | Mirvis et al. (2016) | knowledge-based view | qualitative (case study) | positive | social capital | – |

| Paper 34 | Liu et al. (2020) | social role theory; stakeholder theory | quantitative (panel data; n=683; multiple regression) | positive | – | personal traits of managers |

| Paper 35 | Scandelius and Cohen (2016) | stakeholder theory | qualitative (case study) | positive | social capital | – |

| Paper 36 | Lai et al. (2015) | – | quantitative (survey; n=500; multiple regression) | - (CSR as a moderator) | – | – |

| Paper 37 | Hu et al. (2022) | stakeholder theory | quantitative (panel data; n=3719; multiple regression) | positive | – | competition intensity; market uncertainty |

| Paper 38 | Huarng et al. (2021) | open innovation theory | qualitative (literature review) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 39 | Gummesson (2014) | stakeholder theory | qualitative | positive | – | – |

| Paper 40 | Bocquet et al. (2019) | institutional theory; decision-making theory | quantitative (panel data; n=1348; multiple regression) | positive | gender and nationality diversity | – |

| Paper 41 | Mithani (2016) | stakeholder theory; attention-based view | quantitative (panel data; n=5999; multiple regression) | negative | – | – |

| Paper 42 | Ban (2020) | systematically distorted communication theory | qualitative | positive | – | – |

| Paper 43 | Collins (1996) | stakeholder theory | qualitative (case study) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 44 | Mohr et al. (2009) | – | qualitative (literature review) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 45 | Brusoni and Vaccaro (2017) | – | qualitative | positive | – | – |

| Paper 46 | Zwetsloot (2003) | – | qualitative | positive | – | – |

| Paper 47 | Maxfield (2008) | economic theory | qualitative | positive | social capital | – |

| Paper 48 | Hanke and Stark (2009) | – | qualitative | positive | – | – |

| Paper 49 | Sullivan (2005) | – | qualitative | positive | – | – |

| Paper 50 | Vilanova et al. (2009) | – | qualitative (case study) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 51 | Husted et al. (2007) | strategic management theory | quantitative (survey; n=500; multiple regression) | positive | – | public attention |

| Paper 52 | Anzola-Román et al. (2023) | resource-based view | quantitative (panel data; n=3713; multiple regression) | positive | – | Organizational-level innovation practices |

| Paper 53 | Chowdhury et al. (2023) | stakeholder theory | qualitative | positive | – | – |

| Paper 54 | Ramus et al. (2018) | – | quantitative (survey; n=139; multiple regression) | positive | – | economic turbulence |

| Paper 55 | Rubera and Kirca(2017) | market-based assets theory | quantitative (panel data; n=85; multiple regression) | positive | – | competitive intensity; branding strategy; market dominance |

| Paper 56 | Mena and Chabowski (2015) | stakeholder theory | quantitative (survey; n=394; multiple regression) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 57 | Varadarajan (2017) | stakeholder theory | qualitative | positive | – | – |

| Paper 58 | Dew and Sarasvathy (2007) | stakeholder theory | qualitative | positive | – | – |

| Paper 59 | Jiang et al. (2020) | institutional theory | quantitative (panel data; n=126; multiple regression) | positive | – | firm age; high-tech status; state ownership; legal development |

| Paper 60 | Gutierrez et al. (2022) | stakeholder theory | quantitative (panel data; n=3916; multiple regression) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 61 | Phillips et al. (2019) | stakeholder theory | quantitative (survey; n=262; multiple regression) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 62 | Candi et al. (2019) | – | quantitative (survey; n=254; multiple regression) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 63 | Murphy and Arenas (2010) | stakeholder theory | qualitative (case study) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 64 | Husted and Allen (2007a) | resource-based theory | quantitative (panel data; n=473; multiple regression) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 65 | Blanco et al. (2013) | stakeholder theory | quantitative (panel data; n=595; multiple regression) | positive | – | – |

| Paper 66 | Duan et al. (2022) | industrial organization theory | quantitative (panel data; n=100; multiple regression) | positive | product market competition | enterprise life cycle |

| Paper 67 | Ilg (2019) | resource-based theory | qualitative (case study; literature review; interview) | positive | social capital | – |