This study examines the innovation process through the interrelationships of entrepreneurial orientation (EO) dimensions in an emerging economy. Using a five-point Likert scale, we adopt a survey approach to measure individuals’ EO dimensions and explore the relationship between proactiveness, risk-taking, motivation, and innovation outcomes. We test our hypotheses using a sample of 466 individuals in Kuwait. Survey data are analyzed using principal component analysis (PCA) and a partial least squares approach. The results indicate that proactiveness and motivation positively relate to risk-taking. In addition, we find that our mediating variable, risk-taking, directly impacts innovation. The is an indirect effect of motivation and proactiveness on innovation, through risk-taking. These findings shed light on the interrelationships among different dimensions within the EO framework, pathways towards innovation, and provide meaningful insights for promoting innovation outcomes.

EO is widely recognized as a fundamental driver of entrepreneurship and innovation. EO has been identified as a key concept in the literature explaining the practices and processes behind entrepreneurial actions (Desset al., 1997). According to Miller (1983), EO is the propensity to take calculated risks, innovate and become proactive. The literature has expanded this multidimensional construct to refer to characteristics encompassing several dimensions, including innovation, risk-taking, proactiveness, autonomy, and competitive aggressiveness (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Wales, 2016). Understanding the relationship between these dimensions is imperative for organizations and individuals alike, especially those seeking to promote innovation and enhance competitiveness in the global dynamic business landscape (Alshanty & Emeagwali, 2019; Lumpkin & Pidduck, 2021). The interplay between these dimensions, especially as they relate to the process of innovation, plays a key role in the creation of new business forms (Al-Mamary & Alshallaqi, 2022; Saura et al., 2023), adoption of novel technologies (Guo et al., 2022), and creation of new social forms (Philipson, 2020). However, it remains elusive (Louçã, 2014) and understudied, particularly in emerging economies. While extensive research examines EO, studies focusing on the interplay of EO dimensions as they relate to the innovation process at the individual level are relatively scarce.

Innovation, that is, the process of creating and implementing new ideas and processes, is a fundamental driver of entrepreneurship (Drucker, 1985; Schumpeter, 1934). It allows organizations to create value and is key to their success and sustainability (Hermundsdottir & Aspelund, 2021; Teece et al., 1997). The primary objective of this study is to examine the interaction between the different dimensions of EO and identify new dimensions in the innovation process. Specifically, we aim to answer the questions: How do EO dimensions relate to the innovation process? Do other factors, such as motivation, shape the innovation process?

By gaining insight into these relationships, we aim to unpack the innovation process and contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the underlying mechanisms. Further, we intend to shed light on the relationships between different EO dimensions and how a new dimension, namely, motivation, may relate to the EO construct and innovation process. Motivation is closely linked to creativity and exploration (Benedek et al., 2020). It drives persistence at work (Fishbach & Woolley, 2022), productivity (Amabile & Pratt, 2016; Cerasoli et al., 2014), and ultimately, innovation (Fischer et al., 2019; Løvaas et al., 2020).

Our exploration of EO can provide valuable insights and advance the academic discourse in several ways. First, whereas innovation is often perceived as being generated through a sudden spark in creativity, our study unpacks the innovation process to show that innovation at the individual level is a process. This process involves several steps and dimensions that can be developed through an individual's propensity to take risks and maintain motivation. We contribute by demonstrating the mechanisms behind the innovation process. Second, we shed light on the innovation process through the EO construct to enrich the existing models with a newer dimension and examine the interplay between them. By uncovering the mediating pathway to innovation through risk-taking, we show the indirect effects of individual risk-taking and uncover the specific steps in the innovation process. This approach offers a more nuanced understanding than the direct effects of proactiveness alone and provides a deeper understanding of individual innovation mechanisms. Third, by identifying indirect variable effects, we offer practitioners richer insights into designing more effective interventions and bringing about the desired innovation outcomes within their organizations. Shedding light on innovation antecedents can improve the current understanding of innovation and encourage the development of best practices in organizations and educational institutions based on these mechanisms. We explore entrepreneurial attitudes in a non-Western emerging economy context. This strategy provides unique insights into innovation as an economic driver of sustainable development in an understudied context where data are scarce.

This paper is organized as follows. In the following section, we introduce the concept of EO and its key dimensions, review the literature, and develop the hypotheses. Section three presents the study's design and methodology, detailing the data collection and analytical techniques. In section four, we discuss the results and findings of our research. Finally, section five provides the implications of the findings and recommendations for future research.

Theoretical background and hypothesesEntrepreneurial orientationThe original EO construct was first introduced by Miller (1983) to capture the degree of entrepreneurship demonstrated by individuals and firms. EO refers to attitudes and practices that emphasize the propensity to innovate and explore new opportunities for value creation. Miller's (1983) conceptualization of EO encompasses three dimensions: proactiveness, risk-taking, and innovation. Miller (1983) suggests that the degree of EO of individuals or organizations may vary according to how well they encompass these three dimensions. Lumpkin & Dess (1996) refine the framework to include five dimensions: autonomy and competitive aggressiveness and the initial three dimensions of innovation, risk-taking, and proactiveness. Lumpkin & Dess's (1996) conceptualization suggests that EO captures the processes, practices, and decision-making activities that precede new entry.

Over the past several decades, researchers have emphasized the value of EO in innovation and strategic renewal (Covin & Slevin, 1989; Dess & Lumpkin, 2005). Despite advancements in EO research, EO continues to be perceived as an obscure black box, while conventional conceptualizations aggregate the construct without sufficient inquiry into its interrelationships and inner workings (Kreiser et al., 2002). While the literature has identified several interesting moderators to test, there is little consensus on what constitutes a suitable moderator (Rauch et al., 2009), especially concerning the innovation process. Kreiser et al. (2002) suggest that EO research should assess the connections among different dimensions to develop a deeper understanding of the construct. A meta-analysis of EO research calls for further study of the EO construct, especially investigating the interrelationships between its dimensions (Miller, 2011; Rauch & Frese, 2006; Wales et al., 2021). This is particularly important for shedding light on innovation processes.

Our research aims to uncover the relationships between Miller's (1983) three EO dimensions and introduce a new dimension, namely, motivation. We include motivation because it is closely tied to creativity, exploration (Benedek et al., 2020), persistence (Fishbach & Woolley, 2022), productivity (Amabile and Pratt, 2016; Cerasoli et al., 2014), and our crucial variable of interested, innovation (Fischer et al., 2019; Løvaas et al., 2020). Innovation implies overcoming obstacles in new ways. We contend that motivated individuals are more likely to persevere through challenges (Fishbach & Woolley, 2022) and find creative solutions (Benedek et al., 2020) when encountering challenges.

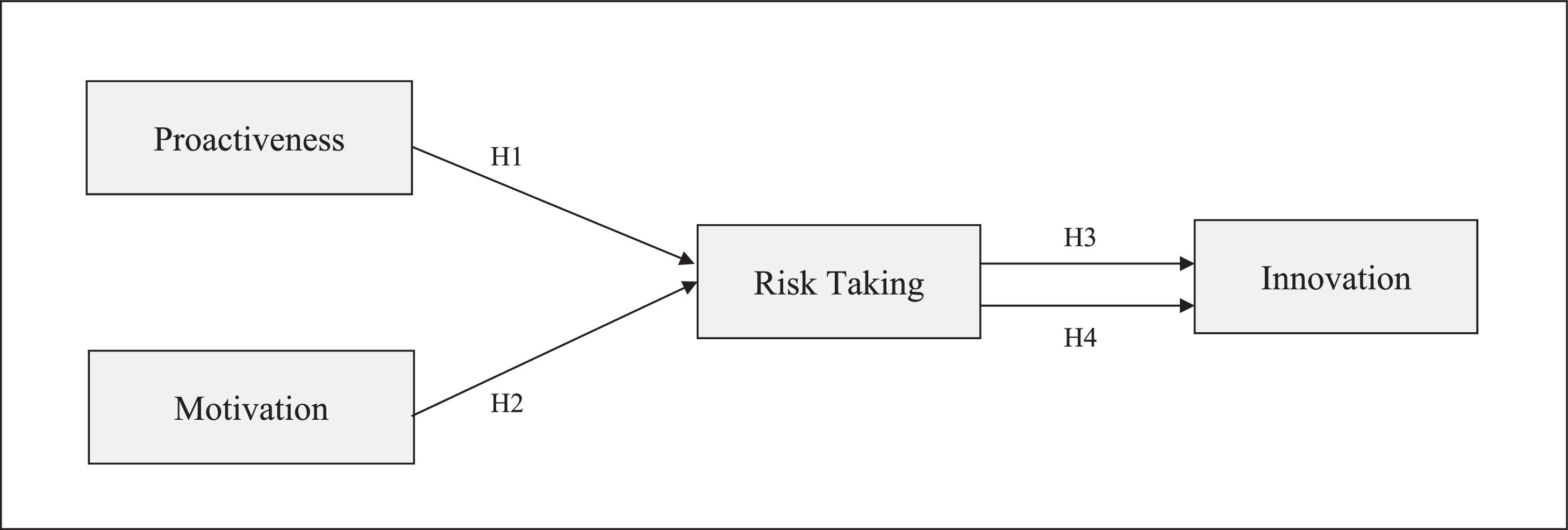

Specifically, we examine innovation as an outcome of proactiveness and motivation, with risk-taking playing a mediating role. Innovation inherently involves risk-taking (Garcia-Granero et al., 2015; Rapport et al., 2022), exploring and experimenting with new ideas, and stepping into the unknown to take chances when the outcomes are uncertain (Liu et al., 2023; Mai et al., 2022; Rapport et al., 2022). Innovators must be willing to embrace uncertainty and engage in actions that do not provide perfect knowledge of the outcomes in their attempts to discover something new. While Pérez-Luño, et al., (2011) found a link between innovation, proactivity, and risk-taking, their research does not examine its relationship with motivation. Thus, by drawing from previous literature, we argue that risk-taking is an antecedent to innovation, and that proactiveness and motivation precede risk-taking. We propose an extended EO model that includes the original dimensions of proactiveness, risk-taking, innovation, and motivation. Fig. 1 presents the research model for direct and indirect effects.

Entrepreneurial orientation in an emerging economyEmerging economies are often characterized by higher levels of risk and uncertainty (Kafka & Kostis, 2024; Marquis & Raynard, 2015; Rindova & Courtney, 2020; Soluk et al., 2021), variable levels of education (Mbiti, 2016; Muysken & Nour, 2006), limited access to finance (Nabisaalu & Bylund, 2021), and strong maintenance of the status quo that discourages disruptive behaviors. Given the dynamics of emerging economies, innovation may be more challenging. For example, limited access to finance can constrain investments in innovation. Variable levels of education may limit the attainment of higher levels of expertise and skills essential for innovation.

These dynamics create a unique landscape for investigating innovation, mainly because disruption is inherent in innovation. Innovation often involves challenging the existing processes and systems (Bertello et al., 2024; Fallon, 2022). Addressing these challenges requires creative solutions that are contextually embedded and relevant to the existing dynamics (Asheim & Isaksen, 2002; Richter & Christmann, 2023; Trippl & Bergman, 2021). Examining innovation in an emerging economy can improve knowledge in an understudied context, contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the EO construct, and bring about transformative changes for sustainable development.

HypothesesRisk-takingRisk-taking is often conceptualized as a choice between options that can lead to positive or negative outcomes (MacPherson et al., 2010; Zinn, 2019). Knight (1921) defines risk as a situation in which the probabilities of different choices are known. Other scholars incorporate probability components and perceptions of internal control into their definition of risk-taking (de-Juan-Ripoll et al., 2021). They describe risk-taking as a decision-making process that inherently involves uncertainty, where the decision-maker evaluates positive and negative outcomes associated with each probability (de-Juan-Ripoll et al., 2021).

Risk-taking occurs at different levels, with some involving higher stakes (Buelow, 2020; Kreilkamp et al., 2023; Zinn, 2019). In some types of risk-taking, the individual has no control over the outcome, which depends entirely on external factors such as luck (i.e., tossing a coin). Other types of risks involve individuals’ actions in terms of the outcome (Kreilkamp et al., 2023), and depends on factors within one's control, such as knowledge, skills, and effort (Zinn, 2019). Individual values determine the choice ultimately selected, such as a less profitable responsible option versus a more profitable non-responsible option (Arieli et al., 2020; Goodell et al., 2023), as well as the calculated expected outcomes of each choice, such as long-term and sustainable profitability versus short-term profitability. The costs and benefits of the choice are often weighed against the costs and benefits of the potential gains and losses in the expected outcomes without definite knowledge of the possible return (Duell et al., 2018). People are more likely to take risks when they value the success that comes with the risk (Buelow, 2020; Byrnes, 1998).

Proactiveness and risk-takingProactiveness is the tendency to create, change, and shape an environment (Fay et al., 2023). Proactive individuals are described as those who are not restricted by situational forces (Fay et al., 2023) and will “scan for opportunities, show initiative, take action, and persevere until they reach closure by bringing about change” (Bateman & Crant, 1993, p. 105). They establish a connection with the future and experience their work as meaningful. In contrast to passive persons, who are more likely to adapt, endure circumstances, and passively hope that externally imposed changes will work out, proactive individuals engage in activities to make things happen. In entrepreneurship, proactiveness refers to openness to new experiences, self-reliance, self-efficacy, and work centrality (Van Ness et al., 2020). In doing so, they may dominate competitors through bold actions, such as “seeking new opportunities which may or may not be related to the present line of operations, introductions of new products and brands ahead of competition” (Venkatraman, 1989). This attitude includes the tendency to seize opportunities and dominate competitors through bold action (Keh et al., 2007).

Proactive individuals are self-leaders (Abid et al., 2021; Inam et al., 2023) who constantly search for opportunities for improvement and make strong efforts to prepare for the future (Dada & Fogg, 2016; Van Ness et al., 2020). They may be inclined to take risks when the outcomes depend on their individual abilities and efforts. The potential reward for achieving future goals drives them to embrace uncertainty and take risks to realize positive outcomes. They desire to be pioneers (Wiklund & Shepart, 2005) and actively seek solutions to problems rather than wait for them to arise (Crant, 2000). This may lead them to take risks to fulfill their potential and realize future goals. Thus, we hypothesize:

H1: A direct positive relationship exists between proactiveness and risk-taking.

Motivation is the “degree to which an individual wants and chooses to engage in a specific matter” (Mitchell, 1982). Mitchell (1982) suggests that motivation is an individual phenomenon that is intentional and predictive of behavior. Motivation begins with unsatisfactory needs (Mullins, 2002), and can be driven by competition or contribution (Grant & Shandell, 2022). The three needs predictive of successful motivation and performance are economic rewards, intrinsic satisfaction, and social relations (Mullins, 2002). These unsatisfied needs drive the behavior required to satisfy needs and achieve goals (Bandhu et al., 2024), completing the motivational process.

According to Atkinson's (1964) conceptualization, motivation is built on motives and expectations. Motives refer to approaching a type of incentive, while expectations refer to an evaluation of whether their actions will lead to the desired outcome (Atkinson, 1964; Bandhu et al., 2024; Cobb-Clark, 2011). Intrinsic motivation is characterized by feelings of joy, interest, and satisfaction (Bandhu et al., 2024; Ryan & Deci, 2020). Neuroscience research suggests that intrinsic motivation governs exploration and play (Di Domenico & Ryan, 2017). Highly motivated individuals believe that they have the power to produce results and thus may be more willing to take risks in pursuit of fulfilling an unsatisfied need (Atkinson, 1957; Dewett, 2007; Salas-Rodríguez et al., 2023). The benefits associated with success may outweigh the perceived costs of risk-taking and drive the thrill of pushing boundaries (Van Duijvenvoorde et al., 2016). Higher motivation levels can lead individuals to feel more confident about their abilities (Muschetto & Siegel, 2021) and overcome the potential consequences of risky decisions. Motivation is often linked to excitement, curiosity, exploration, and play (Bandhu et al., 2024; Di Domenico & Ryan, 2017). These positive emotions can enhance individuals’ tolerance of risk and make them more willing to take chances and pursue their desired outcomes. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H2: A direct positive relationship exists between motivation and risk-taking.

Innovation has been recognized as one of the main values of entrepreneurial orientations (Gardner, 1994; Kraus et al., 2023; Pérez-Luño et al., 2011). Drucker (1985) defines innovation as "the specific tool of entrepreneurs, the means by which they exploit change as an opportunity for a different business or a different service" (1985, p. 19). In the EO literature, innovation refers to the propensity to develop new ideas, technologies, or practices through experimentation and creative processes (Dess & Lumpkin, 2005; Lumpkin & Dess, 2001). Vora et al. (2012) broadly conceptualize innovation in the EO literature, including all methods that create or adopt new products, services, or activities. This definition allows various activities to fit the EO conceptualization of innovation. In most conceptualizations, innovativeness captures the tendency to challenge the status quo and support new ideas, technology, processes, or product development (Baker & Sinkula, 2009).

Risk as a mediator to innovationRisk-taking drives innovation (Da Silva Etges & Nogueira-Cortimiglia, 2019; Hock-Doepgen et al., 2021; March, 1987). Hamel (2000a: 147) suggests that innovative firms take risks and lead the revolution to “knock history out of its grooves.” Innovation requires pushing boundaries and venturing into unchartered ground. Risk-taking allows individuals to pursue new and unconventional ideas. Research shows that bold actions and decisions are necessary to achieve innovative results (Kock & Gemünden, 2021; Latham & Braun, 2009). Taking risks often involves thinking outside the box and exploring new solutions. This fosters creativity and breakthroughs. According to Peters (1997; 27), risk-taking is essential for innovation as “incrementalism is innovation's worst enemy.” In firms, risk-taking refers to the propensity to allocate significant resources to choices that have the potential to reap high benefits (Garcia-Granero et al., 2015). Managers vary in risk propensity according to their level of proactiveness and motivation and their evaluation of possible gains from risky decisions.

According to Tzeng's (2009) review, innovation not only emerges from the properties of the knowledge itself but also from the personal commitment required of a revolutionary. A personal sense of duty is indispensable to innovation (Schumpeter, 1942). Innovation requires “personal responsibility,” and creating new combinations “requires personal force” (Schumpeter, 1942).

Proactive attitudes lead to radical creativity (Zhang & Xu, 2024), risk-taking, and innovation (Alikaj et al., 2021). Research shows that risk-taking is associated with entrepreneurial activities (Macko & Tyszka, 2009) and that innovation is closely related with proactiveness and tangible outcomes (Borins, 2000). Proactivity refers to initiating or engaging in action, rather than waiting passively and reacting to the environment (Van Ness et al., 2020). This view suggests that risk-taking is an antecedent to innovation, and individuals’ perceptions of control and proactiveness can explain risk-taking as a mediator of innovation.

Similar to proactiveness, motivation facilitates the risk-taking activities that drive innovation. Motivation begins with unsatisfied needs (Mullins, 2002). Some needs are related to economic rewards, while others are related to intrinsic satisfaction (Salas-Rodríguez et al., 2023). Innovation is driven primarily by intrinsic motivation rather than extrinsic rewards (Bandhu et al., 2024; Stern, 2004). When people are motivated, their brain-reward systems are activated, releasing dopamine (Wise, 2004), which enhances learning, promotes creative thinking, and the ability to make novel connections between ideas. To be creative and innovative, individuals must engage in activities they love (Amabile & Conti, 1997). Innovation is an iterative process that requires persistence (Andreini et al., 2022) and risk. Motivated individuals are more likely to persevere through trial and error and continue to refine their ideas to reach a discovery. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H3: Risk-taking mediates the relationship between proactiveness and innovation.

H4: Risk-taking mediates the relationship between motivation and innovation.

Kuwait provides a unique context for studying EO. It is a relatively small country that was primarily economically driven by pearl trade, prior to the discovery of oil in the mid-20th century (Al-Ebraheem, 2014). The discovery of oil transformed Kuwait's economy from its reliance on traditional industries such as pearl diving, to oil production and export. While oil exports currently dominate the economy, there is a growing demand for economic diversification away from oil exports towards more sustainable sources of income (Shehabi, 2020), alongside efforts to develop a knowledge intensive economy (Matallah, 2023). The governments growing focus on economic diversification and long-term sustainability has led to a rising awareness of the importance of human capital development, entrepreneurship, and innovation. More recently, government programs have emerged to support innovation and entrepreneurship ecosystems (The National Fund, n.d.). Initiatives made by the government include funding programs, incubators, and regulatory reforms, aimed at establishing a conductive environment for novel ideas and startups to flourish.

Innovation and entrepreneurship are integral components of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Kuwait Vision 2035. UN SDG 9 (Industries, innovation, and infrastructure) focuses on promoting sustainable industrialization and innovation (United Nations, n.d.). Similarly, Kuwait Vision 2035, a strategic development plan aimed at transforming Kuwait's economy, focuses on advancing competition, diversification, innovation, and long-term sustainable economic growth (World Bank, 2021). Individual innovation underlies these initiatives. By understanding individual innovation mechanisms, a culture of creativity and risk-taking can be fostered to align with sustainable development objectives.

Data collectionWe designed a questionnaire based on the following dimensions to investigate the innovation process. In total, 800 administrative and public sector employees were invited to participate in the research project. The participants were from various government departments and agencies to obtain a broad range of perspectives and experiences. Data were collected in 2023 using a self-administered questionnaire. Questionnaires were distributed and collected over six months. The methods employed involved internet surveys. First, we used a small pilot sample to examine the structure of the dimensions. We tested the items’ reliability and validity within the dimensions using Cronbach's alpha and total item-rest correlation. The remaining data were collected. A total of 446 questionnaires were administered and used in this analysis. Partial least squares (PLS) analysis was used to test the hypotheses. All analyses were performed using SmartPLS software.

Measures and assessment of goodness of measuresData were collected using a questionnaire that employed a five-point Likert scale for each construct of the research model. A Likert Scale was employed to assess attitudes (Willits et al., 2016), allowing us to determine the degree of each construct. The measures utilized for each construct in this study to assess the EO and motivation dimensions were derived from existing literature. Appendix A presents items, scale types, and authors.

Goodness of measuresValidity and reliability are the two main criteria used to assess the quality of the measures. Reliability pertains to the extent to which a measuring instrument consistently assesses the concept it intends to evaluate. Validity refers to the degree to which an instrument accurately measures the specific concept it is designed to assess (Sekaran & Bougie, 2010).

Construct validityThe concept of construct validity refers to the degree to which the results achieved from the measure are in line with the theories that the measure is designed around (Sekaran & Bougie, 2010). This approach was used to evaluate whether the instrument used to measure the concept aligned with the theorized concept. Convergent and discriminant validity are two methods used to validate the measures. The loadings and cross-loadings are presented in Table 1. Cross-loading refers to a situation in which an indicator exhibits a larger absolute loading on a latent variable than what it is intended to measure (Henseler et al., 2015; Sanchez, 2013).

Loadings and cross-loadings

Note. The bolded items are the specified loadings for each indicator.

A threshold of 0.6 was employed as a cutoff value for loadings, as suggested by Hair et al. (2010). If any items exhibit a loading greater than 0.6 on two or more variables, they are considered to have substantial cross-loadings. The items selected to measure each construct lead to high scores. This result suggests that the items demonstrate strong validity in measuring the targeted construct and confirm construct validity according to best practices and recommendations for cross-loadings (Costello & Osborne, 2019). PLS structural equation modeling was used to analyze the data.

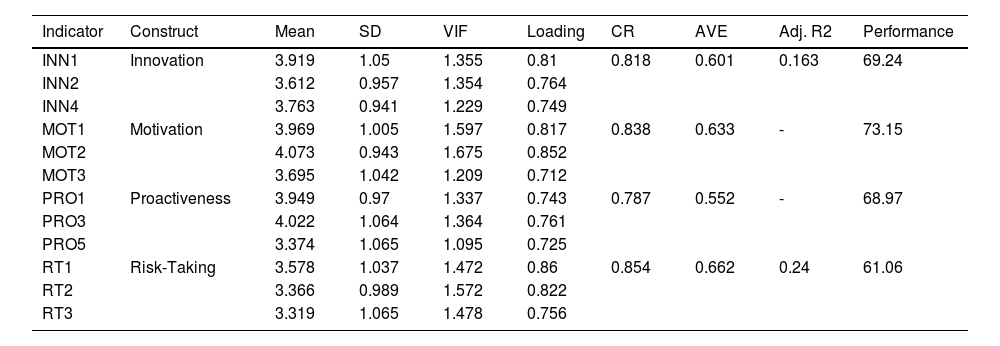

Convergent validityWe assessed the convergent validity, that is, to the extent to which numerous items measure the same underlying concepts. To evaluate convergent validity, we employed factor loadings, composite reliability, and average variance extracted (Hair et al., 2010). The loadings of all the components surpass the suggested threshold. Table 2 presents the composite reliability values.

Composite reliability values

As shown in Table 2, the loadings of the construct indicators range from 0.712 to 0.86. This result is consistent with the recommended value of 0.7 or above. The average variance extracted (AVE) ranges from 0.552 to 0.662. Measures above 0.5 justify using the construct (Barclay et al., 1995). Composite reliability (CR) assesses the internal consistency of constructs while considering the different loadings of indicator variables within each construct (Hair et al., 2014; Hair et al., 2017). This indicator helped evaluate the reliability of the constructs used in our study. A CR of 0.7 and higher is considered to satisfy the CR criteria. AVE is a measure of convergent validity that assesses the amount of variance captured by each construct through its indicators relative to the amount due to measurement error (Hair et al., 2014; Hair et al., 2017). An AVE value of 0.50 or higher is considered adequate convergent validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The Adjusted R-squared value was used to determine the proportion of variance in the dependent variable, which the independent variables can explain. This is a modification of the traditional R-squared method, which adjusts the number of terms in our model.

To gain more insights, this study uses an importance-performance map analysis (IPMA) to identify the dimensions that are most important and perform best and examines multivariate normality using Mardia's standardization coefficient (Ringle & Sarstedt, 2016). The performance indicator measures the overall effectiveness of each construct. Motivation falls into the highest performance category with a value of 73.15, followed by innovation, proactiveness, and risk-taking, at 69.24, 68.97 and 61.06 respectively. These indicators demonstrate the reliability of the constructs in our study and ensure the validity of the results.

Discriminant validityDiscriminant validity measures the extent to which concepts are theoretically distinguished. This test was conducted to ascertain the distinctiveness of each latent variable in the model from the other latent variables. Discriminant validity was evaluated using correlations among potentially overlapping concepts. In Table 1, it can be observed that the diagonal values, indicated in bold, exhibit greater magnitudes compared to the off-diagonal values. This pattern suggests evidence of discriminant validity (Henseler et al., 2015; Sanchez, 2013). Compeau et al. (1999) recommend that items in the model have a stronger loading on their respective constructs. Furthermore, the average variance between each construct and its measures should exceed the variance between the construct and the other constructs.

Discriminant validity mitigates potential problems associated with multicollinearity among the latent variables. To further analyze discriminant validity, we evaluated cross-loadings using the Fornell-Larcker criteria and the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2014). Table 3 presents the results of the Fornell-Larcker criterion.

We compared the square root of the AVE for each construct with the correlation of the construct scores. The diagonal elements correspond to the AVE values of the constructs, whereas the bottom triangular elements indicate the correlations among the construct scores. A violation of the Fornell-Larcker criterion occurs when the correlation between a specific construct and any other construct exceeds the square root of the AVE. All constructs in this study adhere to the Fornell-Larcker criterion, suggesting the absence of multicollinearity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2014).

Another measure used to assess discriminant validity is the HTMT ratio of correlation (Henseler et al., 2015; Sarstedt et al., 2019). Henseler et al. (2015) suggest that HTMT can obtain higher specificity and sensitivity rates than the cross-loading and Fornell-Larcker criteria. The HTMT ratio examines reflective indicators. If the HTMT ratio is greater than .90, multicollinearity among the constructs exists, and the measurement model may not be correctly specified (Gold et al., 2001). The HTMT ratios are listed in Table 4.

Non-response and common method biasWe conducted Harman's single-factor test to address the potential common method bias from single-source data collection. The findings show that a single factor explains 37.28% of the total variance, which falls below the recommended threshold of 50% (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Thus, common method bias is not an issue. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) presented in Table 2 further confirms this result (Kock, 2015). The VIF values for all constructs are below the threshold of 3.3, indicating that the instrument used in this study is free of common method bias.

ResultsDescriptive statisticsTable 5 presents the descriptive statistics. Of the sample collected, 38.8% were male, and 61.2% were female. When analyzing the educational credentials of the participants, 12.6% successfully obtained a high school diploma or equivalent. Additionally, 18.4% had a diploma, signifying the completion of two academic years at a post-secondary institution. The largest proportion (59.4 %) held an undergraduate or bachelor's degree. Furthermore, 9.6% had pursued postgraduate studies, including master's or PhD degrees. With respect to the participants' experience, 22.9% had less than one year of experience, whereas 31.6% had one to five years of experience. Additionally, 17.0% reported having six to ten years of experience, and 8.7% had 11 to 15 years of experience. Finally, 19.7% of the sample had more than 15 years of experience. With respect to occupational positions, a notable majority (73.5 %) were classified as entry- or mid-level workers, while 13.9% held higher positions in the administration. A smaller proportion (3.8 %) were identified as supervisors, and 8.7% were categorized as managers.

Descriptive statistics

Partial least squares path modeling (PLS-PM) analysis was conducted to determine whether the latent variables PRO, MOT, RT, and INNO adequately described the data. The weights of the structural models were calculated using a path-weighting scheme. PLS-PM aims to describe the network of variables and their relationships (Hair et al., 2016). Fig. 2 and Table 6 present the results.

Path analysis to test direct and indirect effects

PLS analysis of the direct effects shows statistically significant relationships between proactiveness, motivation, and risk-taking. The beta coefficients, which measure the magnitude and direction of the relationships, are positive. The R2 value is 0.243, suggesting that proactiveness and motivation explain 24.3% of the variance in risk-taking. The R2 value for innovation is 0.165, indicating that 16.5% of the variance in innovation can be explained by risk-taking. Table 6 presents the detailed results for the direct, indirect, and mediation effects.

The PLS model provides several key insights. First, proactiveness exhibits a strong direct effect on risk-taking, with a coefficient of 0.336 and a t-statistic of 5.945 (p<0.001), supporting H1. Similarly, the direct impact of motivation on risk-taking has a path coefficient of 0.205 with a t-statistic of 3.48, indicating a statistically significant effect (p=0.001) and supporting H2. Furthermore, our mediating variable, risk-taking, directly impacts innovation, with a path coefficient of 0.406 and t-statistic of 10.354 (p < 0.001), confirming strong relationships across these constructs. These results support our hypotheses.

We unpack the indirect impact of risk-taking on innovation by analyzing the total indirect effects in the model. These results demonstrate a significant mediating relationship. The indirect impact of proactiveness on innovation through risk-taking is substantiated, with a path coefficient of 0.137 and a t-statistic of 5.069 (p < 0.001), supporting H3. The indirect effect of motivation on innovation through risk-taking is substantiated by a path coefficient of 0.083 and a t-statistic of 3.059 (p = 0.002), supporting H4. These results demonstrate the indirect effects of proactiveness and motivation on innovation via risk-taking and the importance of risk-taking as a mediating factor that links motivational and proactive attitudes to innovation outcomes.

Finally, we present the total effects of our model, which includes both direct and indirect measures, and reinforce the significant pathways previously discussed. The total effects of motivation on innovation are significant, with a path coefficient of 0.083 and a t-statistic of 3.059 (p = 0.002). The total impacts of proactiveness on innovation and risk-taking are both significant, with path coefficients of 0.137 and a t-statistic of 5.069, confirming the robustness of these effects (p < 0.001). The comprehensive results from the model support not only the direct impact but also the intricate interplay of the indirect effects among the constructs.

Mediation analysis is recommended by Hair et al. (2014) to examine the percentage that carries forward the influence of independent variables on the dependent variable innovation. Hair et al. (2014) propose measuring the variance accounted for (VAF) to assess whether the mediating variables act as full mediators (VAF>80) or partial mediators (VAF = 20-80) or do not show any mediation effects (VAF<20). Our VAF calculations suggest that risk-taking partially mediates innovation through proactiveness and motivation.

DiscussionThis study investigates the effects of various individual-level dimensions on innovation. Previous studies have revealed the relationships between EO dimensions and their roles in entrepreneurial activity (Chowdhury & Audretsch, 2021), entrepreneurial intentions (Koe, 2016), internationalization (Dai et al., 2014), and non-profit organizations (Lacerda et al., 2020). In contrast, our study sheds light on the interplay between EO dimensions in the innovation process. We examine the relationship between the original dimensions of EO, which include proactiveness, risk-taking, and innovation, along with our proposed dimension of motivation, to understand their role in the innovation process. We find that the relationship between these dimensions is significant and positive. Furthermore, our examination suggests that innovation is mediated through risk-taking, either through proactiveness or motivation. Traditional models of innovation research often focus on macro conditions (Shao & Wang, 2023) or organizational factors such as technological capabilities (Camisón-Haba et al., 2019). By exploring the roles of individual proactiveness, motivation, and risk-taking, our study sheds light on the underlying mechanisms in the decision-making process that drive creative problem-solving in innovation.

Our first finding suggests that proactiveness is associated with risk-taking (H1). Those who demonstrate proactiveness make an effort to prepare for the future (Van Ness et al., 2020) and take the initiative to bring about change (Crant, 2000). The potential reward for achieving future goals and the fear of missing out on potential gains can drive them to embrace uncertainty and take risks related to future outcomes, supporting H1. Despite the growing body of research on risk-taking in innovation, few attempts have been made to explore the role of individual proactivity in risk-taking. Shin & Eom (2014) examine proactivity as a mediator between team risk-taking and creative performance. We suggest that individual proactivity, as a driver of change, self-initiative, and future focus, is linked to risk-taking and can be an essential avenue for future research.

Our second finding suggests that motivation is associated with risk-taking (H2). This result aligns with Atkinson (1957), who claims that people with strong motives to achieve are more inclined toward immediate risks. When they believe that they have the power to produce the desired result, they are willing to face uncertainty and take risks to fulfill an unsatisfied need (Bandhu et al., 2024; Mullins, 2002). Highly motivated individuals are more likely to feel confident in their abilities (Muschetto & Siegel, 2021) and experience emotions of joy, exploration, and play (Bandhu et al., 2024; Di Domenico & Ryan, 2017), which enhance their risk tolerance.

We extend our first finding to link proactiveness with innovation through risk-taking (H3). We find evidence that risk-taking acts as a mediator of innovation through proactiveness. In this case, the mediating effect may be explained by proactivity driving individuals to take risks to control future outcomes (Byrnes, 1998; Dada & Fogg, 2016) and fulfill their desire to be pioneers (Wiklund & Shepart, 2005). Previous studies show that individuals who demonstrate proactiveness take initiative to make things happen and are “relatively unconstrained by situational forces” (Bateman & Crant, 1993, 105). However, the link between individual proactiveness, risk-taking, and innovation remains relatively unexplored. Our study offers insights into the relationship between these dimensions.

We extend our second finding to tie motivation to innovation through risk-taking (H4). We find that risk-taking acts as a mediator of innovation. This result aligns with those of previous studies (Amabile & Pratt, 2016; Jiang et al., 2023). According to Amabile (1983), motivation is essential to creativity. More recent studies further demonstrate the importance of motivation in challenging individuals and driving innovative behavior and performance (Cai et al., 2022; Jiang et al., 2023). Highly motivated individuals are more likely to be innovative, partly because they tend to take risks. This attitude may be explained by the fact that innovation is an iterative process that requires persistence and risk (Chiffi et al., 2022), and highly motivated people are more likely to persevere through trial and error until they reach a discovery. Thus, for individuals who maintain motivation, the path to innovation is driven by risk-taking, supporting H4. Our findings highlight the paths and mechanisms underlying individual innovation processes. Considering the two paths to innovation examined in this study, we show that the path from proactiveness to motivation can explain a higher level of magnitude.

ConclusionTheoretical, empirical, and practical implicationsThe theoretical implications of this study lie in explaining individual innovation processes and enriching the EO model. In line with previous theories, we contend that innovation is one of the main values of EO dimensions (Gardner, 1994; Kraus et al., 2023; Pérez-Luño et al., 2011). Our study theoretically demonstrates that the individual innovation process can begin with proactiveness or motivation through risk-taking. Thus, proactive individuals are more likely to be innovative when taking risks. Similarly, motivated individuals are more likely to be innovative when taking risks. Both pathways are valid, but the pathway from proactiveness through risk-taking to innovation is stronger.

Furthermore, we enrich the EO model by examining the interplay between existing EO dimensions and a new dimension, motivation. We empirically demonstrate that motivation can be linked to the existing theoretical EO framework. Furthermore, our study empirically implies that proactiveness can be linked to risk-taking. There is a lack of research examining the relationship between proactiveness and risk-taking. Although this study provides valuable insights into the innovation process through these dimensions, further research is necessary to extend the current understanding of these areas.

By understanding the mechanisms behind the innovation process, institutions can develop more effective innovation strategies tailored to foster environments that encourage risk-taking, proactivity, and motivation. Programs can be designed to nurture these cognitive dimensions and develop the individuals who possess them, ultimately driving societal progress and innovation. Our study is relevant to understanding human attitudes and cognitive processes and helping develop individuals, educational practices, and workplace dynamics that foster innovation. This research can inform theoretical developments, practical interventions, and policy initiatives to enhance innovation.

We offer theoretical, empirical, and practical implications for the existing innovation literature in a unique emerging economy context. Innovation is often perceived as elusive and is generated through a sudden spark of geniuses. This study demonstrated that this process can be honed. This process involves several steps or dimensions that can be developed through an individual's propensity to maintain proactivity, motivation, and take risks.

Limitations and future researchThis study is conducted at a single time point. As a result, developments in entrepreneurship characteristics over time have not yet been captured. Although providing a population snapshot can be beneficial, causal inferences cannot be made without longitudinal data. Future studies could examine individual characteristics over time to explore whether the same relationships persist. In addition, this study is specific to Kuwait. Further studies can expand this model to include multiple countries in developing and developed economies to understand whether the same combination of individual factors leads to innovation.

We conduct this research in the public sector to understand individuals’ innovation particularly in this setting. It provides insights on individuals innovation in one setting, that is often more bureaucratically constrained. These environments often prioritize stability, promotions based on seniority, and allocate resources in a way that support existing processes than new ideas. There are less incentives for innovation. Additionally, there are more women the public sector and this is reflected in our sample. Further research with a larger sample size, encompassing both public and private sectors, and a more balanced gender ratio can improve generalizability and robustness. Given the price that economies and firms pay to increase innovation, future studies can provide valuable guidance for understanding the innovation process and recommend policies to boost innovation in their context.

ConclusionIn conclusion, this study enhances our understanding of the dynamic innovation process by examining the interplay among EO dimensions. Notably, we introduce a novel dimension, motivation, and explore its intricate relationship with other dimensions of the EO construct, highlighting its role in driving the innovation process. Through this exploration, we elucidate the interconnected roles of these dimensions, and illuminate the multiple pathways involved in fostering innovation. Moreover, our study enriches the EO model, through by incorporating a new dimension that underscores the inclination to innovate. In the context of emerging economies, there is a growing interest in examining the indicators of EO dimensions and their relationships with sustainable economic development. Out findings contribute to bridging the gap between existing EO dimensions and motivation, thereby deepening the understanding of how these factors collectively influence innovation outcomes.

We empirically examine the innovation process through the lens of the EO construct in a unique context. The findings of this study provide insights into the mechanisms underlying the innovation process in Kuwait. Our empirical investigation of the EO model identifies critical antecedents of innovation, particularly emphasizing the roles of proactiveness and motivation in facilitating innovation through risk-taking, shedding light on the mechanisms underlying the innovation process. By improving the current understanding of the innovation process at the individual level, we advance scholarly discourse and unpack the innovation process, its components, and its pathways. These insights not only enhance academic understanding, but also provide practical implications for organizations aiming to cultivate environments conductive to creativity and innovation.

CRediT authorship contribution statementNaeimah Alkharafi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Ahmad Alsaber: Validation, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Mohamad Alnajem: Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies.

Scale items questionnaire– the development of a measurement system

| Construct | Items | Scale type | Author |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proactiveness |

| Five-point Likert-type scale | Bolton & Lane (2012); Covin & Slevin (1989); Kreiser, Marino, & Weaver (2002); Miller (1983; 2011) |

| Risk-taking |

| Five-point Likert-type scale | Bolton & Lane (2012); Covin & Slevin (1989); Kreiser, Marino, & Weaver (2002); Miller (1983; 2011) |

| Innovation |

| Five-point Likert-type scale | Bolton & Lane (2012); Covin & Slevin (1989); Kreiser, Marino, & Weaver (2002); Miller (1983; 2011) |

| Motivation |

| Five-point Likert-type scale | Amabile (1983); Atkinson (1957); Polyhart (2008) |