While the general principles of the Institutional Perspective have been widely accepted, there has been only limited consideration to the present time of their in-depth application to the strategies of individual firms engaged in international business. The paper argues that companies engaged in such activities will find that there is a significant gap in precisely what aspects of the formal and informal institutional perspectives need to be identified and assessed for international expansion. The purpose of this paper is to develop a theoretical paradigm that allows organizations not only to compare different countries with regard to their potential for international business expansion from the perspective of Institutional Theory but also drawing on theories of International Business Strategy where relevant. The theoretical framework assumes that such organizations are engaged in analyzing the institutional arrangements and resources of their home and possible host countries. The paper then develops a conceptual framework that identifies five major components, namely people, power, performance, pathways to international expansion, and productivity, the latter being defined in terms of knowledge and innovation. It explores each of these areas in more depth with the aim of adding a more detailed structure to elements of Institutional Theory relevant to international business expansion.

A pesar de que los principios generales de la Perspectiva Internacional hayan encontrado una amplia aceptación, hasta el momento sólo ha habido una consideración limitada de su aplicación en las estrategias de empresas individuales con negocios internacionales. Este artículo defiende que las empresas que participen en dichas actividades encontrarán un vacío en relación a qué factores formales e informales de las perspectivas institucionales se deben identificar y valorar para la expansión internacional. El objetivo de este artículo es desarrollar un paradigma teórico que permita a las organizaciones comparar el potencial de expansión internacional de diferentes países desde el punto de vista de la Teoría Institucional basándose, al mismo tiempo, en teorías de Estrategias de Negocios Internacionales cuando se precise. El marco teórico asume que dichas organizaciones se dedican al análisis de acuerdos institucionales y de los recursos de los diferentes países. El artículo desarrolla un marco conceptual que identifica cinco componentes principales: población, poder, rendimiento, vías de expansión internacional y productividad (definiendo productividad en términos de conocimiento e innovación). El artículo explora cada una de estas áreas en mayor profundidad con el objetivo de añadir una estructura más detallada a los elementos de la Teoría Institucional relacionados con la expansión de los negocios internacionales.

When the American food company Kraft (now Mondelēz International) acquired the UK chocolate company Cadbury in 2010 for $19.5 billion, it analyzed the institutional framework of its acquisition, including its legal and tax implications, and then moved the company headquarters to Switzerland. In an earlier move in 2002, the UK vacuum cleaner manufacturer Dyson moved all its manufacturing facilities from the UK to Malaysia following a careful analysis of the institutional differences between the two countries: the Institutional Perspective on international business strategy is a significant contributor to company development (Peng, Wang, & Yi, 2008). However, the detailed factors that are important from the Institutional Perspective in international business expansion remain unclear at the present time.

Institutional theory at the macro level has been well established for many years, particularly since the work of North (1990, 1994, 2005) and Scott (1995, 2001). They argued that both formal rules, such as the constitution of a country and its legal framework, and informal constraints, such as the customs of the country and its self-imposed rules of conduct, need to be understood in the assessment of the business potential of a country. Thus for example, it has been widely established that some countries are more successful than others in attracting foreign direct investment (World Bank, 2014), whereas other countries perform better in terms of productivity and innovation (Cahn & Saint-Guilhem, 2010; Gwartney, 2009). Institutional theory has long offered important general insights in international literature in the field of international business (Dunning & Lundan, 2008). There have been analyses at the country level covering international relations and political-economic issues, related at least in part to government and company negotiating (Eden & Potter, 1993; Hennart, 2015; Kobrin, 2001; North, 1990, 2005; Rodrick, 2000). These institutional perspectives have been complemented at the firm level by some individual studies of company networks, culture and related sociological issues. These determine – in part at least – the ways that companies manage, work and take decisions on international business issues (Hofstede, 1980; Kogut, 1992; Leung, Bhagat, Buchan, Erez, & Gibson, 2005; Vasudeva, Spencer, & Teegen, 2013; Westney, 1993). Firm-level institutional analysis can usefully draw on the work of Scott (1995) who identified three types of institutions, namely the normative, regulative and cultural-cognitive. Institutional processes derive from collective experience, education, social norms and mimetic societal rules. Amongst other commentators, DiMaggio and Powell (1983) proposed three principle processes for institutional diffusion – coercive, normative and mimetic.

In the context of international business strategy, this paper accepts that these distinctions and processes of the Institutional Perspective are important. However, we argue that they are incomplete for three reasons. First, they make the assumption that such considerations are clear and unambiguous whereas such issues are complex and involve a larger number of stimuli than an organization can possibly process (March & Simon, 1958). This suggests that a paradigm identifying the major elements will be beneficial to companies. Such a paradigm does not exist at the present time. Second, a static view of the institutional perspective assumes that companies must accept the inevitable outcome of such institutional structures and have no means of influencing or adapting to such structures. In practice, companies have choices with regard to countries from an institutional perspective, but they need a structured way of analyzing such countries. A more detailed paradigm of the Institutional Perspective will help companies to analyze the dynamics of both the companies themselves and the changing nature of the country institutions in which they are potentially or actually involved (Dunning & Lundan, 2008; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997). The paradigm proposed in this paper presents such a method. Third, the Institutional Perspective needs to help the ability of companies to gain new knowledge about country institutions and also to contribute through innovation because these two topics have the potential to change the rules of the game in a fundamental way with regard to country choice and company negotiation with countries (Bruton, Ahlstrom, & Puky, 2009; Chandler, 1986; Dunning, 1995, Chapter 5; Lynch & Jin, 2015; Peng et al., 2008; Verspagen, 2006). To summarize, the broad principles of the Institutional Perspective are not sufficiently detailed for firms considering which countries to select when expanding internationally. The detailed and comprehensive formal and informal institutional issues that need to be identified for a country and their implications for international business expansion remain largely unexplored. Hence, the purpose of this paper is to develop a theoretical framework which enables the in-depth comparison of organizations in different countries regarding their potential for international business expansion from an institutional perspective.

It follows that the contribution of this paper is the development of a such new paradigm. It employs elements of both institutional theory and international business theory to develop a new, more detailed framework of the factors that will influence the development of international business strategy at both the country and company level. To the best of our knowledge, this is a significant gap in our existing knowledge and represents the first time that such a paradigm has been proposed. We argue that the paradigm will apply in many areas of international business: developed as well as developing countries, small as well as large companies, entrepreneurial activity as well as more commodity-oriented business. Such a framework is important for companies engaged in international expansion strategies because it addresses an early and important consideration in the assessment of which countries to enter and how to engage with host countries beyond the entry phase (Kogut, 2002; Tallman, 2001).

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. The next section provides a general review focused on the literature of the Institutional Perspective resulting in the identification of the five elements of our proposed paradigm. The following section then explains these elements in more depth. The final section is then a discussion of the implications of the paradigm for companies engaged in international business strategy.

Literature review and theoretical backgroundBy ‘Institutional Perspective’, we mean both the formal national rules – such as those from a country's constitution, its legal framework and regulations – coupled with the informal country factors – such as norms of behaviour, unwritten conventions and self-imposed rules of conduct – that determine and deliver activities in each country (North, 1990, 1994, 2005). Such institutional arrangements impact on organizations and individuals in indirect but influential ways (Scott, 1995, 2001, 2002). The decision-making of both organizations and individuals is consequently impacted by such institutions (Hitt, Alstrom, Dacin, Levitas, & Svobodina, 2004). Thus, the fundamental concepts of the Institutional Perspective include, ‘The beliefs, codes, cultures and knowledge that support rules and routines’ (March & Olsen, 1998: 22). In addition, institutions also deliver results, performance, outcomes and purposefulness (Powell & DiMaggio, 1991). The institutional perspective covers policy perspectives, leadership, management and professionalism at both the country and company level. As we explain later, elements of our paradigm reflect directly these fundamental principles and also provide underpinning assumptions for our proposed structure.

Many distinguished scholars have explored aspects of the institutional perspective in the context of international business and other aspects of international political and economic activities (Chandler, 1986; Gomez & Sanchez, 2013; Porter, 1990; Tan & Wang, 2011; Zacharakis, McMullen, & Shepherd, 2007). From national and global perspectives, it has been argued that institutions form the foundation and structure for market and extra-market based economic and social development. Research includes studies of international relationships, international political economy and territorial relationships (Eden & Potter, 1993, Kobrin, 2001; Grosse, 2005). In addition, business historians have also explored the role of institutions (Jones, 2004; Jones & Khanna, 2006; Wilkins, 2001). Likewise, other perspectives include those of Hofstede on culture (1980) and the work of a number of distinguished scholars on the relationship between strategic choice and the formal and informal constraints bounded by institutional frameworks (summarized in Peng et al., 2008: 923). From another wholly different perspective, both Stiglitz (1998) and Sachs (2001) have offered powerful critiques of some world institutions that have provided both policy and guidance on institutional development. For the purposes of this paper, we have chosen to focus on the institutional aspects that relate directly to international business. Both Dunning and Lundan (2008) and Peng et al. (2008) have provided useful reviews and perspectives that have guided the development of the proposed paradigm described in the next section.

Finally, we note the particular importance of the institutional perspective in relation to developing countries. ‘It is research on emerging economies that has pushed the institution-based view to the cutting edge of strategy research. This is because the profound differences in institutional frameworks between emerging economies and developed economies force scholars to pay more attention to these differences in addition to considering industry- and resource-based factors’ (Peng et al., 2008: 923). Our aim with this paper is to provide structure and guidance that will enable the practical application to the international business strategy especially for companies from emerging countries.

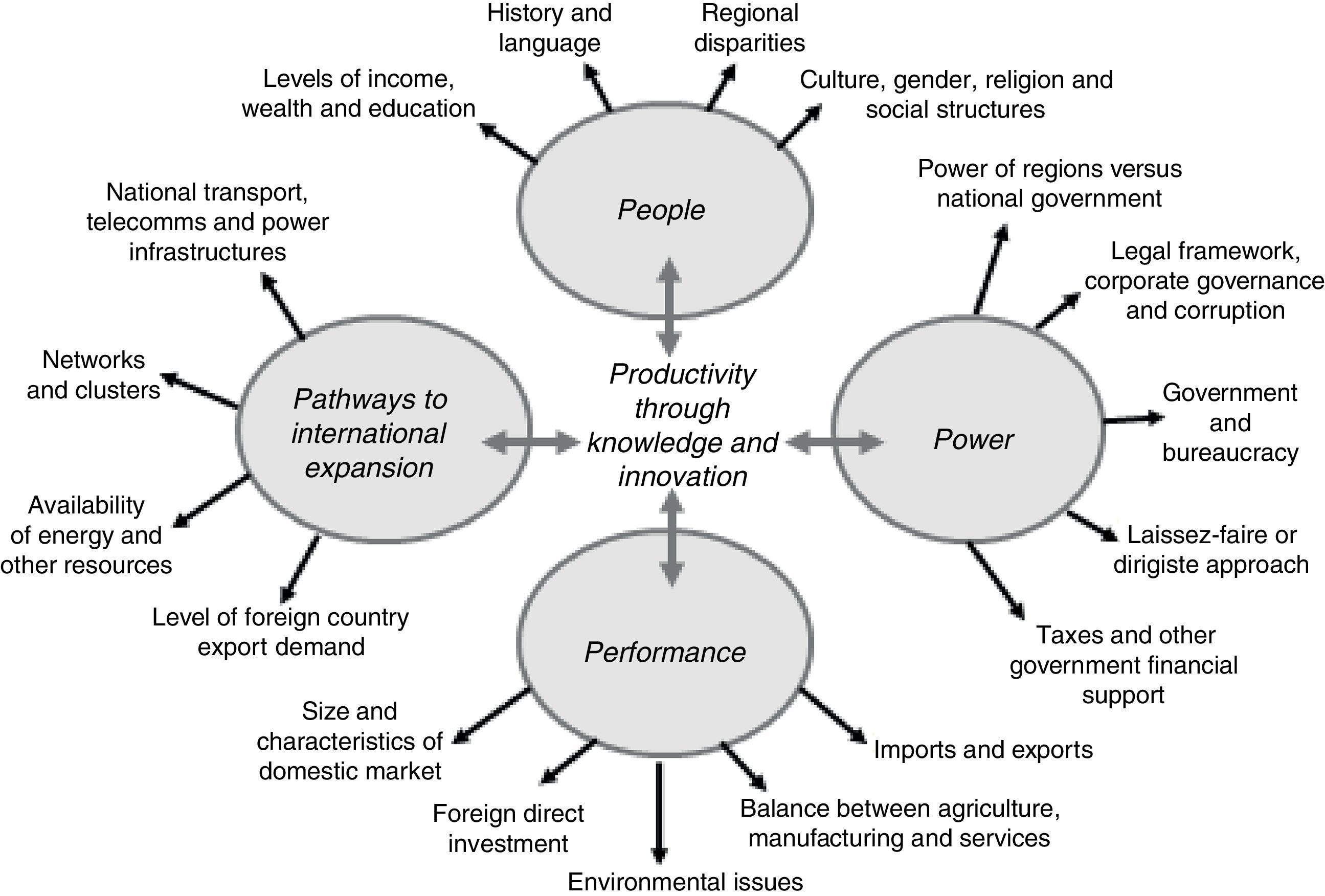

In developing our structuring of the institutional perspective with regard to international business, we argue that all the elements that influence this approach interact with each other. Some elements will be more dominant in some countries and in some contexts than others. Moreover, the balance will change over time and in relation to events outside the individual country. Because of these inter-relationships, the various elements are not simply a possible list of pointers but form a paradigm of factors that work together in various ways (Dunning & Lundan, 2008). We use this general survey of the institutional perspective to identify the first four principle elements the paradigm: namely, people, power, performance and pathways. The outcome of these four elements then delivers the productivity impact of country institutions defined in terms of both the increased knowledge and new innovation at both the level of the industry and of individual companies: the fifth ‘P’ of the paradigm. Hence, the delivery of enhanced productivity through increased and shared knowledge and innovation is the underpinning principle of the paradigm. This is supported from two perspectives: first, increased productivity is a widely accepted business objective for companies engaged in assessing international development opportunities (Peng et al., 2008; OECD, 2015); second, the role of knowledge and innovation hardly needs extensive justification as being amongst the prime elements of productivity to deliver competitive advantage and increased value (Damanpour, Walker, & Avellaneda, 2009; Grant, 1996; Leonard, 1995; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995).

The relationship between the five factors is shown in Fig. 1. Each of these elements is then examined and justified in more depth in the next section.

The five main elements of our proposed paradigmWe begin by identifying and explaining the five main elements of our proposed paradigm. We then explicate each of these elements in the section that follows.

People: The people of a country, including the many basic matters covered in the formal statistical analyses undertaken by such bodies as the World Bank and the United Nations to capture the main characteristics of a country such as age, social class, employment and education levels (see, for example, World Bank Report 2014). We also include here the past history and culture of a country which will have a profound influence on its future development, especially in the areas of innovation, entrepreneurial activity and the contribution of family companies (Hofstede, 1980; Kirkman, Lowe, & Gibson, 2006; Leung et al., 2005; Wang, Freeman, & Zhu, 2013). There have been many papers that support this element of our proposed paradigm.

Power: The way that a country is governed, the balance between the various power groups and the underpinning political and social philosophies of a country have long been established as highly influential in the development (or otherwise) of international trade. We formally note that we make no judgement on the merits or demerits of the democratic and other forms of government. We simply remark that this is a relevant aspect of any such analysis (Bruton et al., 2009; Keefer, 2004; Kennedy, 1990; Koopman & Montias, 1971; North, 1990, 1994; Rodrick, Subramanian, & Trebbi, 2002).

Performance: The results and other outcomes of international trade policies need to be linked to other aspects of the institution-based factors. These are mainly economic and financial and well developed recognized in international data and national statistics (see, for example, the reports of IMF and UNCTAD 2007).

Pathways to international expansion: The policy issues of a country, its government and its people do not necessarily and immediately impact on trade and investment matters. There are a number of intervening elements that are essentially structural in their ability to deliver or hinder international trade: for example, good or bad telecommunications and other communications services. We have attempted to identify what we regard as the main pathway issues in the Institution Perspective view based on international studies of such matters (see, for example, the extensive infrastructure studies in UNCTAD and World Bank Reports for 2006–2014).

Productivity through knowledge creation and innovation: This paper proposes that the guidance of Eisenhardt and Santos (2002: 140) is fundamental to company decision making from an Institutional Perspective: ‘Knowledge is conceptualized, as a resource that can be acquired, transferred or integrated to achieve sustained competitive advantage.’ Both knowledge and its decision-making consequence, innovation, are fundamental criteria in the process of selecting from the many complex potential issues that form the Institutional Perspective. Hence the paradigm proposes at its centre the concept of ‘Productivity’ defined as both the knowledge and the innovation that are derived from a company analysis using the Institutional Perspective. More specifically, we observe that, according to OECD (2001:11), productivity “is commonly defined as a ratio of a volume measure of output to a volume measure of input use.” We also note that productivity is important as it is often linked to international competitiveness (Van Biesebroeck, 2009), knowledge creation and innovation (Morey, Maybury, & Thuraisingham, 2002; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995).

Towards a more detailed frameworkAlthough we have identified the five main elements of the paradigm, these are not detailed enough to allow us to analyze specific international trade situations. We therefore explore each of these five headings in more depth.

Under our People dimension, we have identified four main elements:

Levels of income, wealth and education: The extent and levels of these factors have long been considered as key determinant of economic growth (World Bank Report 2014). In particular, the level of education and the knowledge of language are relevant to international trade.

History and language: The background history related both to company development and more general trends with regard to international trade and other relevant issues (North, 1990, 1994; Stiglitz, 1998). In addition, there is a well-established literature that links company history with strategy development both nationally and internationally (Chandler, 1986; Jones, 2004; Teece et al., 1997).

Regional disparities: Within each country, there are often differences in language, culture, minority ethnic issues, wealth and related matters that influence international business (see, for example, World Bank Report, 2014).

Culture, gender, religion and social structure: These and related sociological factors have long been seen as significant in international business development (Hofstede, 1980; Kirkman et al., 2006; Perlmutter, 1969). We include within this aspect of our dimension, innovation and entrepreneurial orientation. In addition, we highlight the relevance of family ties, family business and family support networks in the development of economic activity.

Personal freedom: This is the extent within which individuals can freely move with certain area, engage economic activities, and express their ideas and concerns (Gwartney, 2009).

Power covers five main areas:

Power of regions versus national government: There are some countries where important decisions with regard to international business are taken at regional level rather than national level. Equally, there may also be competition between regional governments and a desire by regional governments to continue to support companies for their benefits to local employment.

Legal framework, corporate governance and corruption: There are some aspects of a country's legal framework that impact either directly or indirectly on international trade issues. For example, issues related to foreign ownership and investment and issues related to contract law and employment. Corporate Governance has become an important issue for international business, as witnessed by some aspects of the 2009 global downturn. Corruption has long been identified as important to some aspects of international business (see, for example, UNCTAD 2008 on legal issues; Dunning & Lundan, 2008 for a summary of the latter two aspects).

Government and bureaucracy: The role of those involved in setting and implementing policy with regard to international trade and development has long been established. This aspect will also influence many other factors within the overall paradigm. In addition, the role of bureaucracy and the degree of flexibility in the system may also influence international business (see, for example, North, 1990, 1994, 2005).

Laissez-faire or dirigiste: This basic distinction between the two approaches to government action and intervention has long been recognized as fundamental to international trade (see, for example, Koopman & Montias, 1971).

Taxes and other government financial support: These topics, which also cover such matters as special export areas, have always had a strong influence on the way that international trade has developed (see, for example, UNCTAD 2008).

Performance has five main elements:

Imports and exports: One of the main outcome measures of any international trade – widely accepted in any trade analysis.

Balance between agriculture, manufacturing and services: It is well-established that more advanced economies move from agriculture to manufacturing and, at a later stage, increasingly towards a service economy (see, for example, World Bank Report 2014).

Environmental issues: Although these are often primarily of concern to the country itself, we judge that the impact on neighbouring countries may become more significant over time. Thus, issues such as global warming and air pollution from one country that impacts on other countries deserve to be included as part of the paradigm. However, these are relatively new considerations in international trade and do not necessarily have universal acceptance (see, for example, the negotiations surrounding the Kyoto Treaty).

Foreign direct investment: Capital and fixed investment by foreign companies have long been established as an important aspect of company performance. However, the scope of this category needs to be broadened to include investment in knowledge, R&D and other less precise measures that may also impact on international business activity.

Size and characteristics of the domestic market: Porter's research on the competitive advantage of nations showed that such issues as the competitive nature of domestic markets and the support structures for such markets can have an impact on the international competitiveness of nations and their industries (Porter, 1990). To some extent, these are input factors that might be identified in other areas of our paradigm, as well as performance outcomes. However, we have judged that their primary impact comes in the performance of the nation so we have chosen to place them here.

Pathways to international expansion has four main elements:

National transport, telecoms and power infrastructures: The costs, investment and general quality of these items are important in terms of the speed and costs of undertaking international trade. The balance between road, rail and air transport and the distances to be covered are also important aspects of this area.

Networks and clusters: The ability of a nation to handle efficiently (or otherwise) its imports and exports through specific, named locations is an important factor in international trade. The quality, extent and reliability of these factors will have a significant impact not only on costs but also on speed of response to change.

Availability of energy and other resources: The costs of various forms of energy, the ability of a nation to rely on its own energy resources and other forms of power represent important structural influences on a nation's ability to undertake all forms of production and processing. These factors are important in the general context of a nation's economic growth but specifically have an impact on its ability to trade internationally.

Level of foreign country export demand: In an increasingly smaller world with greater responsiveness to change, cheap and reliable communications have become more important. These matters will have an immediate impact on the ability of a nation and its individual companies to compete internationally.

Productivity can be measured in a number of ways.

These measurements can be either quantitative or qualitative (Teng, 2014) in multiple dimensions namely: technology change/growth, efficiency, real cost savings, production process benchmarking, living standards, etc. It is closely linked to technology advance and innovation.

Discussion and conclusionsThe strength of our proposed standardized approach – the ‘5P Framework – in analyzing countries and industries is that we have attempted to cover all the main factors from an institutional perspective. We address two important issues:

First, the institutional perspective is itself a broad and all-encompassing approach to international business analysis, as we showed in our summary of the literature on the topic. In other words, the wide-ranging nature of this perspective must itself pose difficulties for the collection of evidence on companies and industries and for the development of any framework to capture such evidence. We argue that our paradigm is helpful in identifying and structuring the main elements. The ‘5P Paradigm’ therefore has value.

Second, we argue that it assists the analytical process of companies engaged in international business expansion by providing a structured and reasoned analysis of a complex topic. In particular, our proposed 5P Framework offers one important insight that is not covered in market-based and resource-based alternative concepts (Peng et al., 2008).

The ‘5P Framework’ therefore represents an attempt to reintegrate international business strategy from the Institutional Perspectives. Gladwin, Kennelly, and Krause (1995) suggested that reintegration is one of the most important tasks for management theorist. The structural factors identified by the 5P Framework – including government policies, political beliefs, centralized decision-making, family companies, entrepreneurial tradition, national infrastructures, etc. – are the pre-conditions that then lead to the economic factors like low wage costs, barriers to trade and industry concentration according to our evidence.

In this sense, the 5P Framework of the Institutional Perspective relates to the cause rather than the outcome of many factors that are identified in market-based and resource-based approaches. Our proposed framework for the Institutional Perspective hence represents a new way of structuring and understanding this causality. It inevitably provides new research opportunities for academics and implications for practitioners.

The authors thank Dr. Bal Chansarkar, and Dr. Yi Zhu, Middlesex University, UK, for their helpful suggestions on an earlier version of this article. They also thank Professor Arno Haslberger, Webster University Vienna, Austria, for his careful reading and suggestions for revisions to an earlier version of this paper, Dr. Martin Sposato, and Maria Jimenez, Middlesex University, for their help in the translation of the Abstract into Spanish. We thank the anonymous reviewers of the journal for their comments on an earlier version of the paper and corrections for the Spanish version of the abstract.