There has been a growing interest in open-source innovation and collaborative software development ecosystems in recent years, particularly in industries dominated by intellectual property and proprietary practices. However, consortiums engaged in these collaborative efforts often face difficulties in effectively balancing the competing dynamics of trust and power. Collaborative knowledge creation is pivotal in ensuring long-term sustainability of the ecosystem; knowledge sharing can take place by steering trust judgments toward fostering reciprocity. Drawing on a longitudinal case study of the Open Subsurface Data Universe ecosystem, we investigate the intricate interplay between trust and power and its pivotal influence on ecosystem governance. Our investigation charts the trajectory of trust and power institutionalization and reveals how it synergistically contributes to the emergence of comprehensive hybrid governance strategies. We make the following two contributions to extant research. First, we elucidate a perspective on the conceptual interplay between power and trust, conceiving these notions as mutual substitutes and complements. Together, they synergistically foster the institutionalization and dynamic governance processes in open-source ecosystems. Second, we contribute to the governance literature by emphasizing the significance of viewing governance as a configuration of institutionalization processes and highlighting the creation of hybrid forms of governance in complex innovation initiatives.

The open-source movement, recognized as a form of open innovation, has revolutionized the software industry by championing a “connect and develop” strategy (Chesbrough & Appleyard, 2007; Sakkab, 2002). The success of open-source projects, such as Linux, depends on a combination of people, codes, tools, governance modes, and various underlying infrastructure and algorithms (Shaikh & Henfridsson, 2017; Shaikh & Vaast, 2018, p. 2). By freely providing source codes, such projects foster innovation (Baldwin & Hippel, 2011). Therefore, specific governance mechanisms and strategies that effectively address aspects of openness, engagement, interdependence, and coopetition should be implemented (Leiponen et al., 2022). Prior literature has focused on open-source projects from different perspectives, including organizational structure and governance (O'Mahony & Ferraro, 2007; Raymond, 1999; Shaikh & Henfridsson, 2017; von Hippel & von Krogh, 2003); contributors’ incentives and user participation (Lakhani & von Hippel, 2003); interorganizational partnership and organizational decision-making (Shaikh & Levina, 2019); and governance concerns and tensions (Shaikh & Cornford, 2009). Most of these studies have concentrated on open-source projects, such as Linux, that involve both individual contributors and independent entities (O'Mahony & Ferraro, 2007; Shaikh & Henfridsson, 2017). We argue that with the growing number of open-source strategic consortiums comprising independent organizations in various industries, such as software (Samuel et al., 2022) and pharmaceuticals (Olk & West, 2020), there is a need to investigate the governance and interorganizational interactions in these ecosystems (Liu et al., 2021). The intricate nature of governing interorganizational collaboration has been extensively studied from a network perspective (Provan & Kenis, 2008) or within the context of open innovation (Remneland Wikhamn & Styhre, 2023). However, the existing literature suggests that there is no universal approach for organizing collaborative innovation efforts, including open-source projects (Ansell & Gash, 2007; Cao & Lumineau, 2015; Ritala et al., 2023; Schaarschmidt, 2023). As a prominent sociological factor, trust plays a significant role in collaborative knowledge creation and guiding governance decisions within an ecosystem to create a trustworthy environment to share knowledge (Zaheer & Venkatraman, 1995). However, imbalanced power relations among ecosystem actors can make the creation of trust rather challenging (Valença et al., 2018). Despite valuable insights provided by previous research on trust and power and on the creation of meritocratic open-source ecosystems (Eckhardt et al., 2014; Valença et al., 2018), we argue that managing power and autonomy and steering trust judgment to foster knowledge sharing and creativity in traditional industries—predominantly driven by a competitive mindset—requires more investigation (O'Mahony & Ferraro, 2007; Schaarschmidt, 2023; Shaikh & Henfridsson, 2017).

This paper addresses the need for a deeper exploration of governance within open-source innovation ecosystems, particularly in terms of understanding the intricate interplay among governance, institutional trust, and power (Autio, 2022; O'Mahony & Ferraro, 2007; Shaikh & Henfridsson, 2017). Due to the social embeddedness of interactions, we argue that greater attention should be paid to institutional contexts and constraints to study open-source innovation ecosystems and identify the most effective mechanisms for social and technical control within these ecosystems. Additionally, Lumbard et al. (2024) argue that open-source community health is an ongoing social construction. Therefore, we propose an evolutionary study of an open-source ecosystem in the oil and gas industry to investigate the interplay of institutional trust and power dynamics.

The following are our primary research inquiries: (1) How is trust institutionalized in interorganizational open-source-based innovation projects? (2) What is the interplay between institutional trust and power? How do these two influence the governance of an innovation ecosystem?

We build on a qualitative case study of the Open Subsurface Data Universe (OSDU) consortium. This ecosystem comprises energy companies, vendors, technology providers, research and development organizations, academics, and corporations that create new digital solutions. Its goal is to develop a data platform that separates data from applications to facilitate industrial digital transformation.

We present a twofold contribution: (1) We introduce different forms of power and trust as prerequisites for establishing frameworks that foster the development of institutional trust within an ecosystem. We demonstrate that while individual and organizational power can act as substitutes for trust in the initial stages of ecosystem formation, in subsequent stages, with institutionalization and the formation of organizational structures, institutional power and trust become interdependent and mutually reinforcing factors. (2) We elaborate on the dynamic nature and hybrid form of governance in complex ecosystems in managing institutional complexity and innovation processes at different organizational levels.

The remainder of the paper is structured in the following manner: In Background and theoretical concepts, we provide an overview of the theoretical bases for studying institutional trust and power in the governance of open-source projects. Next, the adopted method, research design, and case study are discussed. Thereafter, our research results are presented, followed by a section that discusses theoretical and practical implications.

Background and theoretical conceptsGovernance of an open-source ecosystemThe notion of an “ecosystem” was introduced by Moore (1993) from biology into the social sciences to describe the heterogenous cooperative and competitive relationships in innovation projects. An ecosystem commonly refers to loosely coupled, interconnected networks of affiliated organizations that operate beyond their traditional boundaries and collaboratively create capabilities around an innovation (Autio & Thomas, 2014; Moore, 1993). Scholars in various fields use the ecosystem notion, including innovation ecosystems (Autio & Thomas, 2014), platform ecosystems (Gawer & Cusumano, 2014), knowledge ecosystems (Järvi et al., 2018), open innovation ecosystems (Remneland Wikhamn & Styhre, 2023), and open source ecosystems (Jansen, 2014). Adner (2017) challenges the viewing of an ecosystem as a complex array of peripheral organizations gathering around dominant actors or a focal technology, such as a platform to create value; instead, he adopts the ecosystem-as-structures perspective and defines ecosystems as motivation-driven entities with complex interdependencies that prioritizes the centrality of the value proposition. This value perspective advocates ecosystems as sociotechnical assemblages in which the social and technological aspects intersect and influence one another (Orlikowski & Scott, 2008), which is in line with Giddens’ (1984) “structuration theory” and the notion of “infrastructuring” given by Star and Ruhleder (1996). In this study, we adhere to the propositions given by Adner (2017) and Ritala and Almpanopoulou (2017), which focus on innovation activities and the temporal evolution of stakeholders. We conceptualize an open-source innovation ecosystem as a socio-technical structure that facilitates interactions among actors with complex interdependencies, thereby leading to the development of an open-source innovation.

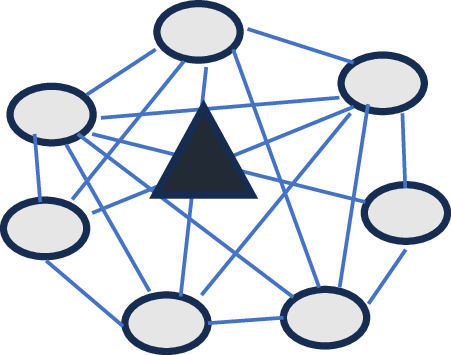

The governance of establishing order, decision-making, and managing opposing logics of value creation and capture to ensure the generativity and cohesivity of ecosystems is rather challenging (Remneland Wikhamn & Styhre, 2023). Governance refers to “all processes of governing” (Bevir, 2012, p. 5). It serves as a means to organize transactions and establish order in situations that involve loosely coupled, interconnected networks of cooptative organizations in which potential conflicts can often jeopardize the possibility of achieving mutual benefits (Williamson, 1999). Governance requires a constant choreography of establishing order, making decisions, and managing opposing logics of value creation to ensure the generativity and cohesivity of an ecosystem (Remneland Wikhamn & Styhre, 2023; Ritala et al., 2023). Complex interdependencies among various actors engender new social orders that necessitate dynamic governance mechanisms (Autio, 2022; O'Mahony & Ferraro, 2007). Shaikh and Henfridsson (2017) categorized governance within open-source ecosystems into three distinct forms based on their underlying authority structures: centralized, libertarian, and collective. The authors highlighted the complexities inherent in the Linux project and asserted that the dynamic evolution of governance and the emergence of hybrid governance forms in expanding open-source communities require a deeper consideration of the dual aspects of governance and coordination. This duality can become particularly intricate when organizing interorganizational open-source initiatives, as it involves a delicate balance between the forces of cooperation and coopetition. The goal is to simultaneously mitigate transaction costs, elevate collaborative performance, and foster innovative outcomes. Consequently, hybrid forms of governance—comprising structural, relational, and administrative governance mechanisms—may emerge as a viable solution (Cao & Lumineau, 2015; Jayaraman et al., 2013). The network governance literature goes beyond the traditional unicentric and “hub and spoke” governance models and considers the complex nature of the task, structural factors, and relationship dynamics (Jacobides et al., 2018; Provan & Kenis, 2008). Different governance modes have been identified, such as lead organization governance, shared governance, Network Administrative Organization (NAO) governance, core-periphery governance, and combined lead/NAO governance (Kenis et al., 2019; Provan & Kenis, 2008). We argue that hybrid and decentralized governance mechanisms are becoming more popular in innovation ecosystems (Shaikh & Henfridsson, 2017) and knowledge networks (Ritala et al., 2023). This is in accordance with the study by van Vulpen et al. (2022), which identifies partner management strategies and emphasizes the benefits of shifting individual governance mechanisms and orchestrations. However, the study by Eckhardt et al. (2014) on the Eclipse open-source ecosystem reveals that evaluating and achieving meritocracy through decentralized governance strategies can also be challenging. Further, Autio (2022) argued that ecosystem governance should occur at different technical, economic, institutional, and behavioral levels. We argue that the emphasis on the importance of the institutional layer is in accordance with Adler (2001) governance model based on price, power, and trust. Among these factors, he identified trust as the most influential in situations that involve knowledge-intensive assets. In noncontractual ecosystems, relational governance concerning trust and power plays a crucial role in designing the collective order of the ecosystem. This approach also minimizes transaction costs, enhances coordination, and enables the adaptive reconfiguration of the social order, thereby reinforcing collective solidarity (Adner, 2017; Cao & Lumineau, 2015; O'Mahony & Ferraro, 2007).

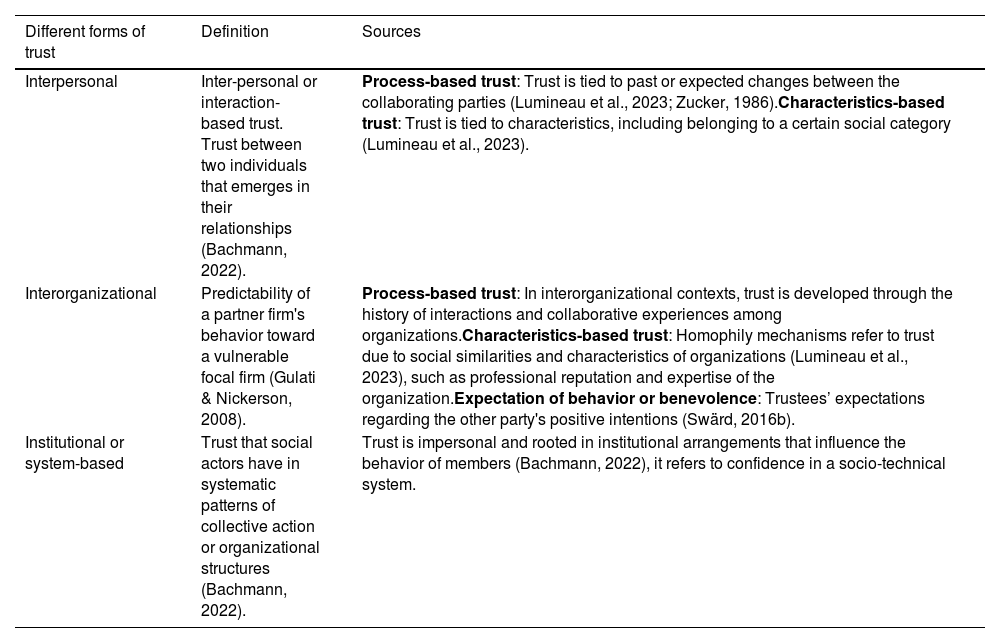

Institutional trust in open-source collaborationTrust is commonly described as the level of confidence and willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party (Mayer et al., 1995, p. 712; Zaheer et al., 1998). In interfirm collaborations, trust-building efforts and risk-management strategies are essential in improving overall exchange performance, and these strategies are highly effective instruments for governing interorganizational relations (Harrer et al., 2023). The literature on trust has its origin in social interactions and extensively investigates trust across two distinct levels— interpersonal and interorganizational—by delving into their interplay (Cao & Lumineau, 2015; Zaheer & Venkatraman, 1995). Lumineau and Schilke (2018) and Brattström et al. (2019) argued for adopting an organizations-as-institutions perspective. These authors drew attention to organizational structures that influence the cognition and behavior of its members and, hence, the development of trust, which they asserted is intricately tied to judgments and decision-making processes impacted by organizational structures (Lumineau & Schilke, 2018). Institutional trust refers to trust in a social system as well as institutionalized roles and routines within organizations (Kroeger, 2012). Therefore, institutional trust can be defined as the willingness of actors to trust an institution enough to make themselves vulnerable to the actions of other actors that, in turn, are guided by and act according to the institution's regulations (Kroeger, 2012; Mayer et al., 1995). Lumineau et al. (2023) challenged Zucker (1986) three modes of trust formation and argued that characteristic- and institution-based trust likely surpasses process-based trust in prominence and importance. Different potential forms of the development of trust in open-source ecosystems are presented in Table 1.

Different forms of the development of trust in open-source ecosystems.

| Different forms of trust | Definition | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal | Inter-personal or interaction-based trust. Trust between two individuals that emerges in their relationships (Bachmann, 2022). | Process-based trust: Trust is tied to past or expected changes between the collaborating parties (Lumineau et al., 2023; Zucker, 1986).Characteristics-based trust: Trust is tied to characteristics, including belonging to a certain social category (Lumineau et al., 2023). |

| Interorganizational | Predictability of a partner firm's behavior toward a vulnerable focal firm (Gulati & Nickerson, 2008). | Process-based trust: In interorganizational contexts, trust is developed through the history of interactions and collaborative experiences among organizations.Characteristics-based trust: Homophily mechanisms refer to trust due to social similarities and characteristics of organizations (Lumineau et al., 2023), such as professional reputation and expertise of the organization.Expectation of behavior or benevolence: Trustees’ expectations regarding the other party's positive intentions (Swärd, 2016b). |

| Institutional or system-based | Trust that social actors have in systematic patterns of collective action or organizational structures (Bachmann, 2022). | Trust is impersonal and rooted in institutional arrangements that influence the behavior of members (Bachmann, 2022), it refers to confidence in a socio-technical system. |

Institutional trust or “system trust” (Luhmann, 1979) functions as an organizing principle that compensates for the lack of regulatory pillars in open-source-based interorganizational ecosystems (Bachmann & Inkpen, 2011). This type of trust forms the foundation for relational governance and informal coordination. It enables diverse perspectives to align in fulfilling obligations, alleviating tensions between cooperation and competition, and striking a balance between individual value creation and community values (Autio, 2022; Autio & Thomas, 2014). However, the formation of trust is complex and incremental; it also depends on the shadows of the past and future in interorganizational collaborations that impact reciprocity in the ecosystem (Möllering et al., 2019; Swärd, 2016b). The shadow of the past is influenced by the previous history of interactions, while the shadow of the future pertains to partners’ motivation to trust each other due to expectations of a common future and potential adventures (Swärd, 2016b). Swärd adopted a social exchange perspective and argued that “reciprocity” (expected behavior from the other party) and “imprints” (expectations based on initial conditions or sensitive situations) should not be mistaken for trust in evolutionary studies on the formation of trust (Swärd, 2016a, 2016b). Imprints refer to the influences that specific periods or experiences have on individuals, organizations, or systems. Imprinting is not about a long-term chain of events; rather, it concerns how short, sensitive periods influence subsequent periods of stability (Swärd, 2016a). Swärd (2016a) explains that the establishment of a new ecosystem or interorganizational relationships are sensitive periods of uncertainty during which partners may carry imprints from the past or develop new imprints based on the situation. These imprints can shape behaviors, attitudes, and practices after the initial events have occurred; however, they may fade or persist overtime based on interactions and relationships.

To understand the development of trust in open-source-based interorganizational relationships, conducting a multilevel analysis of the ecosystem and institutional environment is most important.

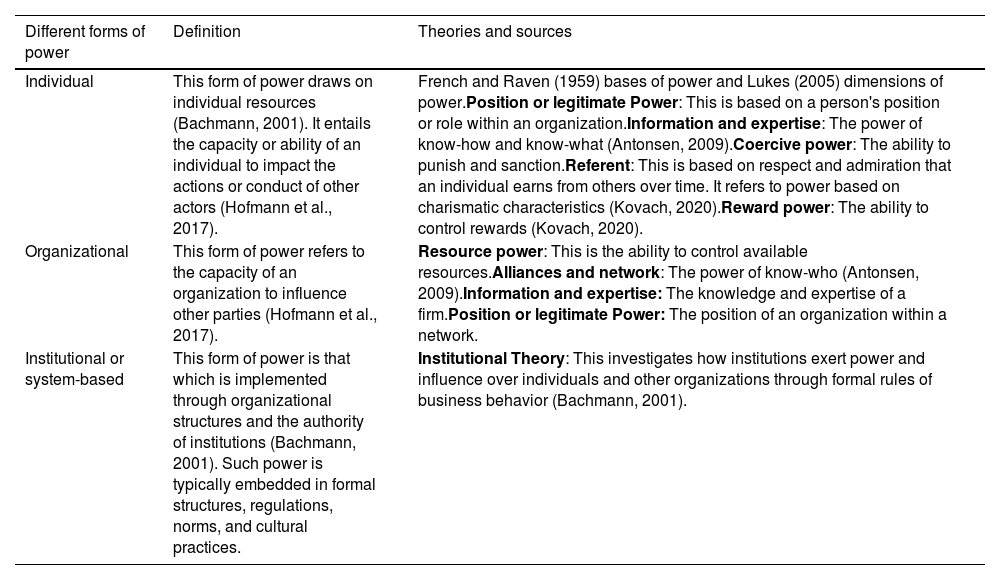

Power relationsPower is the structural capacity of a social actor to enforce its desires and decisions based on other social actors (Castells, 2007). The actor may not directly impose their power or intentionally use sheer force but rather influence other actors’ choices (Jasperson et al., 2002). Institutional systems inherently embody power relations shaped by a historical interplay of domination and resistance, and influential individuals devote themselves to upholding specific values or interests (Castells, 2007; Kroeger, 2012). Hence, social systems often exhibit biases toward the values and interests of certain selected groups, often at the expense of others (Antonsen, 2009). Different forms of power are presented in Table 2.

Different forms of power.

| Different forms of power | Definition | Theories and sources |

|---|---|---|

| Individual | This form of power draws on individual resources (Bachmann, 2001). It entails the capacity or ability of an individual to impact the actions or conduct of other actors (Hofmann et al., 2017). | French and Raven (1959) bases of power and Lukes (2005) dimensions of power.Position or legitimate Power: This is based on a person's position or role within an organization.Information and expertise: The power of know-how and know-what (Antonsen, 2009).Coercive power: The ability to punish and sanction.Referent: This is based on respect and admiration that an individual earns from others over time. It refers to power based on charismatic characteristics (Kovach, 2020).Reward power: The ability to control rewards (Kovach, 2020). |

| Organizational | This form of power refers to the capacity of an organization to influence other parties (Hofmann et al., 2017). | Resource power: This is the ability to control available resources.Alliances and network: The power of know-who (Antonsen, 2009).Information and expertise: The knowledge and expertise of a firm.Position or legitimate Power: The position of an organization within a network. |

| Institutional or system-based | This form of power is that which is implemented through organizational structures and the authority of institutions (Bachmann, 2001). Such power is typically embedded in formal structures, regulations, norms, and cultural practices. | Institutional Theory: This investigates how institutions exert power and influence over individuals and other organizations through formal rules of business behavior (Bachmann, 2001). |

Kroeger (2012) argued that the processes of institutionalization could exacerbate complications between power and trust by making trust more visible or power less visible. The invisibility and unconscious functioning of power were also emphasized in Bråten (1973) concept of “model power.” He distinguished between formal and informal powers and explained how dominant actors—individuals or organizations—in collaborative work can influence the perceptions and preferences of other cooperating actors (Bråten, 1973). The invisible influence on others can, in turn, shape the collective construction of meaning and understanding of a phenomenon in social life. The potent, implicit impact of power is also portrayed in Lukes (2005) “third dimension of power.” Valença et al. (2018) define power in software ecosystems as the influence one organization has on another through its “power capabilities” based on its assets and technologies. They warn against the risks of powerful actors taking advantage of less powerful companies. A power imbalance between stakeholders in open-source innovation projects may lead to a “winner takes all” situation (Cennamo & Santalo, 2013). However, to ensure the health of the ecosystem, Valença et al. (2018) suggest that powerful actors can use their influence to govern the ecosystem and prevent predatory attitudes of dominant key contributors, thereby avoiding centralized decision-making. Bachmann and Kroeger (2017) argue that power in the form of collectively binding law or social standards of business behavior results in “system power” or “institutional-based power.” Institutionalized power and establishing effective organizational structures creates institutional safeguards that reduce opportunistic behavior and, thus, serve as a prerequisite for trust-building and legitimacy in complex business relationships (Bachmann & Kroeger, 2017).

Method and presentation of the case studyThis research adopts a case study and an interpretive qualitative approach (Klein & Myers, 1999) to study the interplay among trust, power, and governance mechanisms in an open-source innovation ecosystem (the OSDU) initiated in the oil and gas industry. We employ a longitudinal perspective using temporal bracketing (Langley et al., 2013). The OSDU officially began in September 2018 as an open-source consortium to develop a standard-base data platform to eliminate data from applications, foster the adoption of data-driven approaches, and facilitate industrial digital transformation. Over the years, the initiative has expanded to an innovation ecosystem for the energy industry to address challenges in the entire energy sector. The ecosystem currently consists of 230 organizations, including global consortiums (the open group), oil and gas operator companies, technology providers and consultants, cloud providers, service and digital product providers, data providers, renewable energy companies, academics, and national oil companies.

There are several reasons why we selected the OSDU data platform as the focal point of our study. First, its diverse range of participants, institutional complexity, and dynamics of interactions and relationships provide the necessary complexity for studying trust, power, and governance mechanisms. Second, studying the OSDU since 2018 has given us access to valuable longitudinal data and, thus, enabled us to track its evolution.

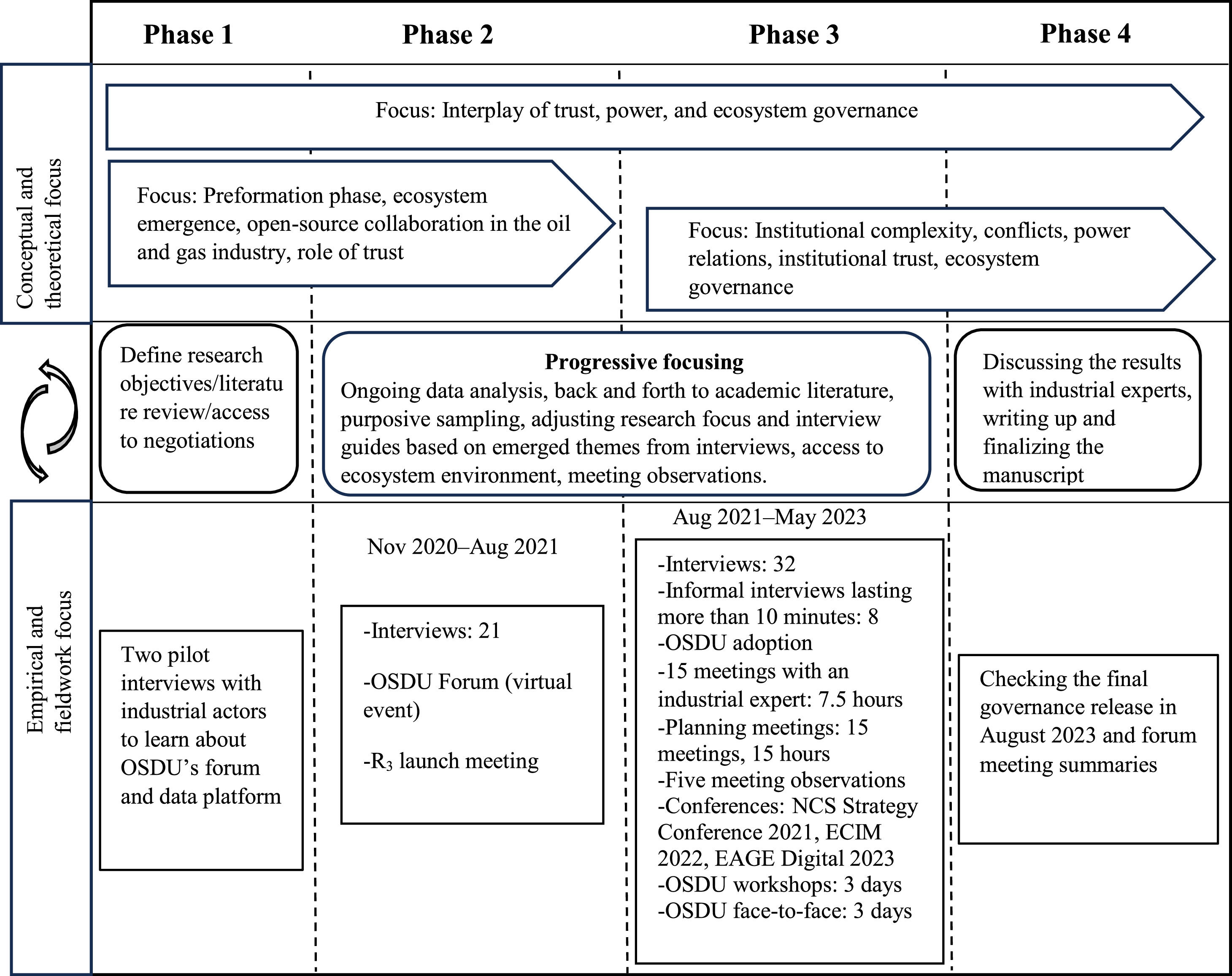

Data collectionInterview and observational data for this study were collected between November 2020 and May 2023. We searched through different archived documents and conducted 55 semi-structured individual and group interviews. The interviews lasted 30–60 min and were conducted face-to-face and via video communication platforms (e.g., MS Teams and Skype). We conducted multiple interviews with selected informants at different study phases, as presented in Table 3, to gain more comprehensive insights and asked follow-up questions to delve into additional details about the evolution of trust and power relations.

Progressive focus of the research, adopted from Almpanopoulou et al. (2019).

We asked open questions in our interviews but developed our own interview guide. Informants were encouraged to share their experiences about developing the new industrial ecosystem and platform, their interactions and communications with other platform members, and their trust in the ecosystem. We selected participants based on a purposeful sampling approach and snowball techniques. Further, we interviewed oil operators (Opt), vendors (V), consultants (C), and cloud providers (CP) to obtain retrospective and real-time accounts. We also observed the slack channel and participated in different meetings, as presented in Table 3. Several ad hoc and informal interviews during conferences, workshops, and related social events were also vital in extending our understanding of the observed ecosystem. We took extensive field notes during all interviews and observations and attempted to remain unbiased during data collection through data triangulation and reflexivity.

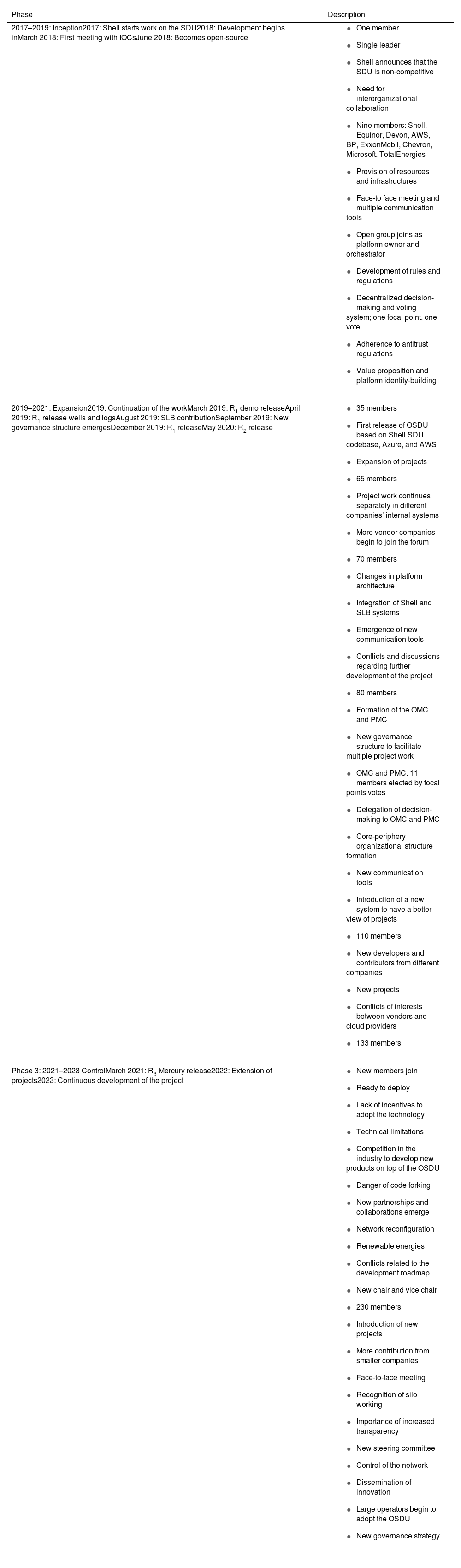

Data analysisTo better understand the evolution of the ecosystem and its dynamics, data analysis was conducted simultaneously with data collection. The analysis began with an iterative process of going back and forth through the collected data, marking relevant passages and collecting descriptive codes by comparing the informants’ perspectives on the research problem. Several rereadings of the interview and field notes provided a foundation for the study; additional archival data from the participating organizations were used to contextualize our interviews. We attempted to remain inductively oriented in identifying the governance and coordination mechanisms of open-source ecosystems. At that time, the previous literature and theoretical concepts proved valuable for coding the framework, conducting the data analysis, and interpreting the findings. To study the evolution processes of the digital ecosystem, we used the temporal bracketing method (Langley, 1999; 2013). Visual mapping by combining different data sources provided multiple perspectives regarding specific events, relationships, interests, key actors, and ecosystem objectives and governance. Temporal bracketing aligns with practice theory, and Giddens's structuration theory enabled us to perceive practices within their temporal context and in relation to social actors and structures. We identified three influential periods to sequence events chronologically in the evolution of the OSDU innovation ecosystem. In accordance with Autio (2022) multilayered framework, we refer to them as inception, expansion, and control.

Findings: evolution of the OSDU ecosystemPhase 1: inception, 2017–2019Our empirical findings reveal that the original idea for developing a data platform to foster innovation in the oil and gas industry was developed in the R&D department of one of the frontrunners in the industry. Recognizing the complexity of the product and the need for significant resources, the company proactively engaged with other major oil companies to collaboratively develop the innovative idea.

“In 2017, Shell decided to see its proprietary subsurface data universe (SDU) as noncompetitive and continue to work on it by sharing across the industry” (Opt7).

The initial formation of the forum occurred informally on the periphery of a conference. Informal relations and interpersonal and competence trust among representatives of the participating organizations played a vital role in initiating this innovation ecosystem.

“Informal relations were important in the formation of the OSDU as most of us who are now working together had never worked together formally earlier” (Opt7).

The participating companies were compelled to redefine their competitive boundaries to create an industrial competitive advantage through collaboration. However, establishing and sustaining such an initiative in the industry is a formidable task given the intricate institutional complexities characterized by numerous actors, objectives, and logics. Contract-based joint ventures and alliances are the most common forms of collaboration in exploring hydrocarbons or developing new products in the industry. Our empirical study on the OSDU reveals that historical legacy, intellectual property, proprietary R&D efforts, product complexity and uncertainty, and the regulatory environment are the leading causes of institutional complexity in the oil and gas industry.

Historical legacy, intellectual property, and proprietary R&D effortsPrevious instances of open-source projects in the oil and gas industry were constrained because of their scale and scope, as the sector is predominantly controlled by several companies that spearhead technology development and innovation through their proprietary R&D efforts.

“The entire industry is proprietary from head to toe, the mindset is proprietary, technology development is proprietary, and all the data is proprietary. I think they do not understand the benefits of being open, and there is a lack of knowledge about the open-source movement in the industry” (Opt15).

This proprietary mindset, with its inclination to emphasize intellectual property—such as patented technologies and exploration data—and its persistence in following traditional business logic and operating principles, can impact collaboration and information sharing among organizations.

Product complexity and uncertainty“The OSDU is a huge project and is a complex task that requires massive resources” (C1).

The complexity of developing the OSDU data platform, the uncertainty of the oil and gas industry due to oil price fluctuations and stringent environmental regulations, and the challenges of previous collaborative initiatives, such as the Energistics initiative (an open consortium that aims to define and develop data standards for the upstream oil and gas industry), make the OSDU a somewhat risky investment.

Regulatory environmentThe oil and gas industry's monopolistic history and antitrust regulations create significant challenges for companies collaborating on large-scale projects. The lack of clarity in market regulation introduces uncertainty regarding the future direction of hydrocarbon production, and the trend toward energy transition is a significant barrier to new investments and broader ecosystem initiatives. In addition, establishing an innovation ecosystem requires that organizations be embedded in different geographical and institutional contexts that are governed by both private and public authorities; these necessities add to the complexity and ambiguity of the regulatory environment.

Independent institutionalization catalystThe members employ an independent institutionalization catalyst to address institutional complexity, facilitate stakeholder collaboration with different organizational structures, and create an “interorganizational constituted practice” (Möllering et al., 2019). The “open group” is a global consortium and legal authority that acts as a “third-party guarantor,” independent intermediary, information mediator, regulator, NAO, and intermediary for innovation (Bachmann & van Witteloostuijn, 2009; Sydow, 1998). The entirety of the OSDU's intellectual property goes to this third-party organization.

“In the beginning, a few people got together informally, and this was the six major oil companies, but then being such a large group of companies, you really need to have a safety net when they start working together; otherwise, it looks like an antitrust problem, so they went to the open group, and the forum was initiated under the open group processes. They got the old antitrust regulations and created all the records of the meeting to follow; the nondisclosure agreement and not permitting sales-creating statements at the beginning of the meetings ensured that everyone was following the rules” (V3).

As the platform owner, the open group remains neutral and is not involved in decision-making or technical development. This increases trust in the ecosystem by facilitating open communication, sharing, creating membership regulations, and providing a framework to control the expectations and behavior of the involved stakeholders.

“I think it is necessary to have a mediator, and it is nice to have someone impartial to be the main sort of organizer of things. I think that we used to have good trust in other bigger companies the same size as us. But I now think that with this collaboration with more companies, both big and small, you can trust more companies when you get to know them better in the ecosystem” (Opt17).

Governance features

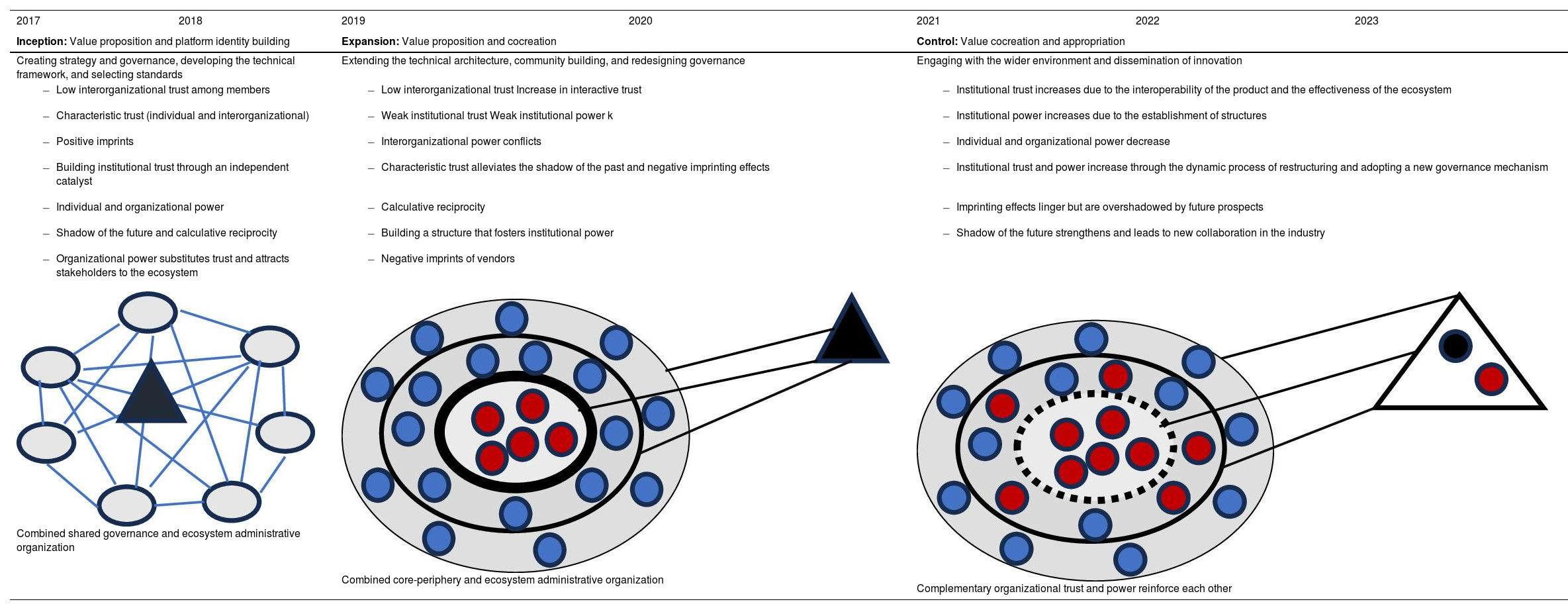

The ecosystem momentum phase mainly concerns creating the required regulations to facilitate collaboration among companies, building platform identity and legitimacy, working on data definitions, and integrating different systems. To facilitate decision-making processes and trust building, a shared voting system was designed, and one vote was assigned to each company. Therefore, a hybrid governance mechanism, combining shared third-party governance, was initially designed. We observed that the independent catalysts handled behavioral and institutional orchestration, while the technical orchestration was managed through the shared voting system. The absence of economic orchestration was notable at this stage. The governance system is intentionally designed to facilitate the formation of institutional and interorganizational trust. The positive feedback from initial informal meetings and having shared objectives created positive imprints of the objectives of the involved stakeholders. Moreover, the contributions and constant interactions among representatives from the participating organizations played a key role in cultivating interorganizational trust. During this phase, the distinct identities and powers of the organizations were of particular importance, particularly considering the pivotal role of one stakeholder as the primary contributor and initiator of the forum. As the lead developer of the data platform, this stakeholder gains organizational legitimacy due to their professional/technical background. This leads to its empowerment in playing a leadership role and influencing collective decisions on strategic and technical issues. In early ecosystem formation, we observed that the ecosystem's governance had a weak institutional framework. Therefore, individual and organizational power sources exerted a significant influence. The official announcement of the forum and increased activities gradually attracted more members. In 2019, during the launch of R1—the first version of the data platform—the forum had 35 members. Our findings demonstrate that the institutionalization process occurs through informational meetings and the sharing of documents by third-party catalysts and representatives from various organizations. These mechanisms are fundamental in fostering interorganizational trust, thereby providing a solid foundation for establishing shared norms and practices.

Phase 2: expansion and value cocreation, 2019–2021After the first launch phase, the focus shifted to fostering growth through network effects to attract more active organizations and resources and expand the project's technical scope. These collaborative efforts among the stakeholders fostered interorganizational trust, thus leading to its reinstitutionalization and influencing other organizations’ orientation toward the OSDU innovation ecosystem.

“Super majors are critical in the OSDU, and without their support, it would not happen. Right? Because, you know, this really started with Shell, and without the other super majors that have gotten on board, it would have never had the momentum that it needed to get attraction. When we saw that all our major customers are highly engaged in this initiative and contributed to it, we thought that we were missing an opportunity if we weren't part of the consortium” (CP2).

The early launches of the OSDU data platform demonstrated its capabilities in developing a new data platform and industry standard and, thus, fostered trust in its performance and proving that the system is reliable and functional. Consequently, more companies were motivated to join the initiative. In this stage, more vendor companies began joining the forum. Major vendor companies are powerful actors and are influential in directing industrial innovation trends. Their business model is based on traditional closed innovation approaches, which has led to the dominance of complex proprietary applications. The OSDU incentivizes these companies to change their competition criteria and participate in developing open-source technology by contributing their proprietary source code to the consortium.

The involvement of vendor companies created a few tensions in the forum that eventually influenced the technical and organizational aspects of the project. The vendor companies’ historical supplier–buyer relationships with the oil operators presented challenges in creating process-based trust. In fact, oil-operators had negative imprints regarding the motives of vendor companies based on previous experiences in standardization projects. However, characteristic-based trust was formed based on recognized competencies and capabilities in developing codes and new technologies. Characteristic-based trust facilitated collaboration and reinstitutionalization as well as provided opportunities to reorganize network and innovation processes; this enabled the successful integration of newly contributed codes into the existing system, (R1), and R2 was launched in 2020.

Governance features

The expansion of the project and its team members, the establishment of subgroups dedicated to various aspects of the product, the lack of transparency in tasks, and differences in the approach and contribution of partners created challenges in managing and coordinating individuals and resources across distinct boundaries. Therefore, a new governance mechanism was required to orchestrate the technical aspects of the project.

“We thought that there is a need for a more day-to-day decision-making authority which did not have to go through the cycle of more than 200 companies voting for every decision” (Opt21).

By increasing the number of members, the power of the open group as an institutional orchestrator decreased, and in the absence of a precise conflict resolution mechanism, the coherence of the ecosystem's institutional framework appeared fragmented. Consequently, the stakeholders involved were more inclined to leverage their power through their contributions to shape decision-making processes and the overall institutional structure.

“When the forum was initially started, we were not making software, so the original version of the OSDU was that mainly the operators would get together to define their needs; they were creating the reference architecture, data definitions, and the information security group to take care of security needs. The original theory was to create a reference architecture and look for cloud providers to implement them according to requirements. But it was changed because the vendor companies brought their code contribution, which then changed the whole model to the point that we were inside the forum developing the open-source data platform. They also brought in a new governance model, and it was then that the OMC [OSDU management committee] and PMC [project management committee] were formed to make decisions on behalf of the focal points” (V3).

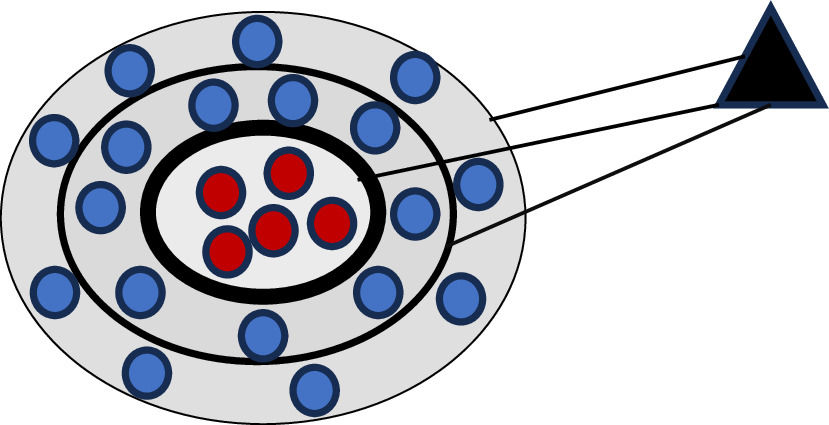

Hence, a chair was selected, and an OSDU management committee (OMC) and project management committee (PMC) were established; their members were selected through an election process with the votes of representatives from various member organizations. The abundance of vendor companies and the relatively fewer oil companies—although the latter were substantial in size, one conflict area during this phase regarding the governance of the ecosystem was to maintain them as operators—prevented the development of proprietary platforms in the community and the formation of an economic battleground. Consequently, each project group comprised eleven seats, which were distributed among five oil operators, three vendors, and three cloud providers. The composition of elected candidates for steering committees indicates that larger companies with more resources and power have a greater likelihood of being selected. This demonstrates that an organization's power is a precondition for trust in its ability to take a leading role in the ecosystem. The adopted governance structure contributed to amplifying a core-periphery structure within the forum, which exemplified a hierarchical organization. The core consisted of OMC and PMC members and the forum's chair. The semi-periphery comprised contributing developers, mainly from small companies, and active users; the periphery included passive and inactive members and users.

We observed that in this phase, the combined governance mechanisms—consisting of the independent catalyst and core periphery—were appropriate for accomplishing complex problems and fostering the institutionalization of trust and power in an interorganizational innovation ecosystem. However, the presence of the vendor companies and the exploration of future business models emphasize a distinct economic misalignment, thereby demonstrating the need to establish a well-defined financial roadmap.

Phase 3: 2021–2023—R3 Mercury release, further development, and adoption of the OSDUIn this phase, core- and semi-periphery members were actively working on developing the OSDU data platform; its first operatable version, R3 Mercury, was released in March 2021. Shortly thereafter, the large oil operators began adopting the OSDU internally, which required collaboration with vendor companies and cloud providers. Interaction within the OSDU ecosystem fostered the establishment of trust among its organizational members. Therefore, we noticed that new industry collaboration modes were emerging. The OSDU also created opportunities for small software and service companies to partner with large oil operators, which was rare in the past.

“We came to the understanding that previous supplier–customer relationships were not good enough, and we want to be partners with our previous customers” (V1).

An interwoven web of personal connections potentially leads to deep levels of trust among reliable individuals from various organizations. Thus, we observe a dynamic between individual and organizational levels of trust. This can even occur in cases where the organizations these individuals represent might not inherently possess a high degree of trustworthiness. This happened for small companies in the forum.

“So, in the beginning, it was more about luck for big vendors and a few companies. Now, we see that there are more companies in the market, and many smaller companies have the chance to develop their own tools and small features, or they can have specialists and analytics tools, those kind of things; it's much easier to do that with an OSDU kind of setup than it was in the past” (Opt17).

“Small companies can be recognized through their contribution. Without the OSDU, it would have been almost impossible for a small vendor company to sign a contract with a large company like Shell; now, we see the dynamic is changing and small vendors are gaining more visibility” (Opt22).

Our findings emphasize a remarkable pattern: when it comes to idea testing, small firms can exert their influence, but mainly on small-scale projects. However, in matters concerning aspects of influential projects and steering committee elections, there is a discernible trend in placing trust in larger companies. While this selected strategy undoubtedly helps stakeholders mitigate uncertainty in intricate decision-making processes, it is important to acknowledge that it could inadvertently compromise meritocratic idea testing. Over time, reinforcing the dominant members might negatively contribute to a competency trap and limit the ecosystem's ability to adapt and innovate effectively. As small companies’ competencies continue to gain increasing recognition, larger companies are making efforts to confer legitimacy upon them through novel collaboration contracts. However, the imprinting effects of perceiving them as less competent in the past do endure and they are still not trusted in large-scale idea testing. This trend is evident in the election results, as most individuals voted based on the company because they preferred it over those that they were unfamiliar with. Therefore, employees of large companies often secured positions as members of the OMC or PMC, which gave them more power in the decision-making process.

“When it comes to innovative ideas and approaches, it is hard to trust small companies because they do not have the competency” (informal interview, operator).

Following the release of R3, OSDU activities—such as product increases and competition among different vendor companies—were visible when the OSDU promoted its proprietary products. The R3 release was a turning point in the interoperability of the OSDU data platform—it strengthened the shadow of the future and increased hope for the platform's success. In addition, expanding the project's scope by developing a data platform for the energy industry attracted more members from renewable energy companies and national oil firms, which expanded the periphery; currently, the forum has 230 members. Therefore, the exchanges are now riskier and more complicated. The expansion of the periphery accentuates the issue of free riding, consequently raising concerns regarding the project's voluntary nature.

“However, the idea of the OSDU data platform is very attractive; thus, the intention of many companies to join the initiative is not clear. It is possible to say that many of the companies joined since they did not want to be left behind or they want to have access to information to prevent losing their dominance in the market” (Opt9).

“I think that there is a big problem in that there is no commercial contract among different parties working on the development of the OSDU and the job is done voluntarily” (C1).

Self-amplifying reciprocity is high in the subprojects, and whenever a company's representative initiates a task, other interested members join the group and voluntarily contribute to its accomplishment. At this level, reciprocity is facilitated through obligation, enthusiastic contribution, and interpersonal trust. However, the initial imprints regarding the motives of companies involved, particularly the vendor companies, may have a detrimental effect on the dynamics of self-amplifying reciprocity within large-scale project endeavors.

“When a company donates a code and they advertise it as part of their current product, it implies that the company is the one that knows most about the base code and how to build applications on top of it. Politically, when it comes to who the major players are, it's clear who has contributed a lot to the OSDU forum. In addition, if one company comes in and donates a code or something to the forum, the competitor company believes that it wants to increase its share or dominance in the forum. So, in the decision-making processes, it tries to vote against it” (V6).

However, members concern that uneven contribution could lead to conflict and hinder innovation processes:

“There are chances to see conflict in the development of the OSDU as many of the companies do a lot of work, but the rest contribute little and only observe the process. This can be a source of conflict and tension, especially when it comes to operation and benefit. It is hard to avoid free riders” (C1).

The team managed to reduce conflicts and tensions through negotiation and by providing more information regarding open-source projects through presentations from the open group and experienced forum members. Aligning divergent interests and crossing pragmatic boundaries to develop a common syntax regarding how the data platform should be developed and disseminated is challenging. However, we observed that reciprocity at this level was more driven by calculative benefit and the shadow of the future, which refers to the success of the OSDU and potential future collaborations.

“The success of OSDU will benefit all of us. So, it is a win-win situation to contribute your codes to the forum” (Opt16).

We discovered that the institutionalization of trust and power through formal organizational structures leads to a decrease in the power of individuals and organizations. The institutionalization of trust leads to a reduction in interpersonal trust and becomes an interorganizationally constituted practice. Even in complex dynamics, trust remains; new members are integrated into established practices (Möllering et al., 2019). Therefore, when a key individual involved in the initiation and development of the OSDU lost his influence, he chose to exit the forum—a decision that did not disrupt the ongoing work. This signified a shift toward a more collaborative decision-making process aligned with the formal forum structure. Consequently, the boards within the OMC and PMC committees acquired greater authority.

“While he was the creative mind behind the OSDU, he gradually lost his authority, and as we gained momentum, we realized that there are more democratic ways of doing the job” (Opt22).

“It's a political monster, but it has been impressively effective. No one thought it would move as fast as it has. But there is this development by committee, and that is always extremely difficult, so I'm very impressed about how fast people have aligned and how fast things have developed and aligned to the goals of the open group” (CP1).

However, interactions among actors and their power dynamics are intricately embedded within a complex web of institutional contexts that are nested and overlapping. A lack of clear guidelines and expectations regarding power dynamics results in conflicts arising from differences in strategic goals among the multiple parties involved. Powerful companies may use their power to disrupt the institutional power of formal decision-making channels.

“I see a stall and late tactic system if something is not going ideally for some particular company; they have the ability to pull the levels of governance and stall decision-making. I am quite shocked…” (Opt21).

“One company was biased toward a certain standard. They pushed that standard; they even reached out to us outside of the forum and wanted us to take their side, vote for the standard, and promote it” (Opt20).

Governance features

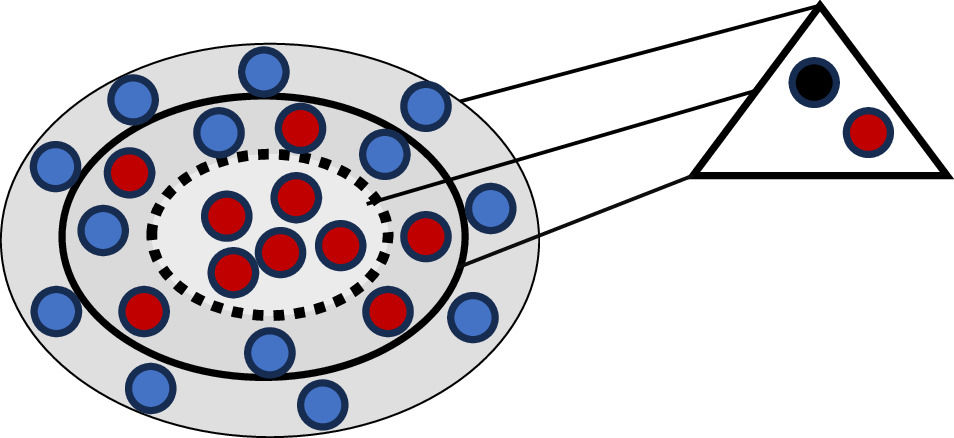

In this phase, we noticed a rise in the authority of the steering committees within the OMC and PMC groups. The increasing institutional power and trust in the formal governance structure reduced the forum chair's capability to uphold a command-and-order leadership style. The formation of formal structures within the ecosystem brought to light a potential issue in the leadership style of the chairperson. Instead of being constructive, his leadership style appeared to have a disruptive influence, particularly regarding institutional processes and technical development. Therefore, a new chair and vice chair were elected with a more administrative role to increase communication between the open group and the organizational members. The aim was to address concerns regarding the formation of a hierarchy due to the core-periphery structure and lack of clarity in the current governance system, which may have disrupted institutional trust and power and slowed the pace of innovation.

“The open group has standard processes for how the other forums work, but we want to make things clearer and see how the governance strategy is going forward because, in a normal forum, they do not normally have 230 companies working together. They had pushed more things to focal points votes in other forums, but in the OSDU, they vote for the people that they elect as members of the OMC or PMC. The project team should make decisions themselves, and if it is about software, they should take it to the PMC and get agreement there and then they should take it to the OMC to get agreement there; then, depending on the size of the impact, it may have to go to focal point votes. The open group will say that it should go through all these levels, and I am not sure why it should go through all these levels. It takes about six months or more, and, to me, that is not a reasonable time to make decisions” (V3).

In addition, federated self-governance mechanisms and stratified idea testing were evident in the project teams. Although crucial for evaluating the idea of meritocracy, siloed work environments and a lack of transparent communication processes among the different project teams resulted in overlaps across various projects, thereby posing challenges for effective management.

“The project teams do the job autonomously and, because of the lack of collaboration between teams, sometimes we do not see that the decision made in one team can negatively impact the other team” (V3).

The first step to address these issues was to create a committee in which an independent catalyst, a chair, and a vice-chair could orchestrate the forum. The goal was to establish a more engaged orchestrator that could monitor organizational members, cultivate a stronger community, enhance feedback loops, facilitate communication between independent catalysts and organizational members, and foster information flow among the core-, semi-periphery, and periphery layers, thereby facilitating the creation of institutional power and trust to amplify contributions. The second step was to clarify the technical orchestration and increase the visibility of ongoing projects to prevent overlapping. This occurred through a redefinition of the working groups and roles. Collaboration between the OMC and the administrative party increased exponentially, and the OMC revived its power as the “executive leadership with operational oversight of forum activities” (Opt21).

Moving forward, the PMC's focus will only be on software production. The new governance model aims to blend the borders of the core and periphery and make it easier for all members to obtain information across boundaries. Therefore, the coordination team now consists of a forum chair and vice chair, an OMC chair and vice chair, a PMC chair and vice chair, working group leads, and the independent catalyst. At this stage, the primary source of conflict revolves around the ambiguity of the ecosystem's business model and lack of economic orchestration mechanisms, which hinder the alignment of interests between operators and vendors. A detailed summary of important events during the evolution of OSDU in different stages is presented in Table 4.

Evolution of the OSDU.

The evolution of the OSDU ecosystem presented in Table 4 illustrates that the organizational structure is constantly changing and different structures coexist simultaneously. We observed that governance is a dynamic process that varies depending on the institutional needs of the ecosystem and the interplay between power and trust at different levels. In this case, the complexity of the task and interactions requires multiple governance strategies beyond the capabilities of one hub-actor organizer. The interplay among organizational trust, power, and the imprints of actors involved in the early stages of ecosystem development make the institutionalization process relatively complex. These imprints are formed based on the companies’ reputation, affiliation to different groups, and conflicts regarding the development of process-based trust. This emphasizes the necessity for an independent catalyst to create a trustworthy ecosystem to facilitate knowledge sharing and value cocreation in the inception phase. While we highlight the role of an external catalyst, the open group, in giving meaning and legitimacy to behavior, we argue that their lack of involvement in technical operations reduces their institutionalization power over time. We observed that the expansion phase was characterized by tensions, conflicts of interest, and power struggles stemming from negative imprints related to participant motives for joining the OSDU. These imprints linger in time and negatively impact reciprocity and collaboration. However, due to the institutionalization processes, establishing structures and routines, characteristic trust, and interactions among representatives of different companies help diminish the imprinting effects. A vision of the future eclipses these imprinting issues, and institutional trust in the OSDU innovation ecosystem drives collaboration.

There is an interplay between trust and power at different levels in the evolution of an ecosystem, as presented in Table . However, individual and organization-based trust and power decrease over time in favor of institutional structures that aim to stabilize these dynamics while accommodating the intricacies of the maturing ecosystem. Individual and organizational power are prerequisites for the development of individual and organizational-based trust in the early stages. However, over time, the institutionalization processes and the development of institutional trust reinforce the institutionalization of power. Establishing structures through self-regulation and formal governance design fosters the institutionalization of trust and power.

In the early stages of the OSDU, organizations continuously wielded their power in the ongoing negotiation processes and impacted governance and shaped the roles, expected behavior, and rules of engagement in the ecosystem. However, in the third phase, institutional power reached a point that outweighed individual and organizational power. In addition, the interoperability of the product strengthened the shadow of the future and increased trust, thereby leading to the effectiveness of the system and ecosystem. Over time, the stakeholders realized the importance of creating social order and adopting a combined extended core-periphery and ecosystem administrative committee governance strategy that facilitated participation and reciprocity by blending core- and semi-periphery borders. We emphasize the importance of directing institutional governance endeavors toward contextual integration, as this change ensures that the regulatory framework evolves in sync with the expanding ecosystem. Simultaneously, as stated by Autio (2022), it proactively adapts to changing regulations.

DiscussionThe findings of this study reveal that trust operates and develops over time and across various levels, including in the individual, interorganizational, and institutional tiers; these levels also mutually influence each other at different stages of ecosystem development. This study contributes to discussions on trust formation and its operation across multiple levels that are intricately nested within each other (Kroeger, 2012; Lumineau & Schilke, 2018). We elaborate on the development of and interplay between institutional trust and power in open-source ecosystems and their influence on its governance. Our contributions to discussions on the dynamics of institutional trust and power and organizational governance in open-source ecosystems are presented below.

Our first contribution is to the discussions on the interplay between trust and power at different levels. According to our findings regarding the evolution of the open-source innovation ecosystem presented in Table 5, as the OSDU initiative progresses and the digital ecosystem matures, trust dynamics may shift from traditional interpersonal and interorganizational trust to a focus on institutional trust and trust in the system, thereby encompassing confidence in governance structures and processes and a belief in the digital platform's performance and capabilities. Our findings reveal that successful releases of different versions of the OSDU data platform have increased trust in the system around digital technology. The belief that the designed organizational structures and governance mechanisms effectively facilitate collaboration and reciprocity, while reducing the opportunistic behavior of competitors, has contributed to the development of institutional trust in the OSDU ecosystem. This development of institutional trust has outweighed the characteristic-based trust in different organizations and individuals that was recognized in the early stages of the ecosystem's formation. The recognition of the important role of institutional trust in open-source ecosystems and interorganizational technology development initiatives aligns with the research of Lumineau et al. (2023). The evolutionary study of the OSDU reveals how the shadow of the future, successful development of technology, potential future collaborations, the shadow of the past, and experiences with vendor companies impacted collaboration and the development of institutional trust. This is in accordance with the study by Swärd (2016b), which emphasizes the role of the shadow of the past and future in shaping collaborations. However, by referring to the collaboration between vendor companies and oil-operators, we argue that the development of institutional trust has reduced the negative effects of the shadow of the past and increased the positive effects of the shadow of the future.

Interplay among trust, power, and governance.

Further, our findings demonstrate that in the early stages of ecosystem formation, where there is a lack of clear organizational structures and weak institutional arrangements, individual and organization-based power reinforce the development of trust in different individuals and organizations. The composition of the steering committees reveals that this trust-based power reinforces the power and domination of powerful actors and their influence in decision-making processes. However, the adopted governance structures and the development of institutional frameworks and structures diminish individual and organizational power and foster institutional power in subsequent stages. This institutionalization of power enhances institutional trust in the ecosystem and demonstrates how these factors complement each other. This institutionalization, in turn, requires the designing of a new governance strategy to increase transparency and improve the flow of knowledge and information in the ecosystem. Therefore, we argue that power and trust coexist, reinforce, and substitute each other at different levels and stages of ecosystem development and, thus, impact the governance of open-source ecosystems. The findings align with other studies that emphasize the complex interplay of trust and power in different interorganizational collaborations (Sydow, 1998; Sydow & Windeler, 2003).

Second, we extend the open-source governance literature (O'Mahony & Ferraro, 2007; Shaikh & Cornford, 2009; Shaikh & Henfridsson, 2017) by observing governance through an institutional lens. Because complex ecosystems rely on organizations with varying structures and business mindsets, the emergence of multiple authority structures becomes unavoidable. While Shaikh and Henfridsson (2017) challenged lead organization governance strategies and emphasized the diversity of governance structures in open source projects, their focus is only on internal power structures. We highlight the role of external power structures, such as regulatory frameworks of the oil and gas industry, in the governance and institutionalization of interorganizational-based ecosystems. Our study reveals that environments with institutional complexities where collaboration among different organizations is rather complicated, the presence of an independent catalyst can facilitate collaboration and ecosystem formation. According to our findings, the alignment of internal and external power structures by the open group has led to the development of institutional structures that encourage reciprocity. Therefore, we highlight the role of independent organizations in orchestrating collaboration and facilitating knowledge sharing as well as co-creating in exaptation-driven open-source projects that are dependent on resources from different organizations and with asymmetric power relations. This is in accordance with previous studies on third party guarantors or network administrators, such as Bachmann and van Witteloostuijn (2009), that emphasize the role of a mediator. Creating effective organizational structures and institutional mechanisms to facilitate collaboration plays a key role over time in enhancing institutional trust in the ecosystem and the technology under development. Establishing institutional trust and power ensures meritocratic idea creation and technology selection and testing that fosters stakeholder contribution and the creative recombination of technologies.

Further, governance based on multiple authority structures that reinforce institutional structures ensures the viability and sustainability of the ecosystem by offering stakeholders the opportunity to design adaptable structures that suit the current situation and enduring frameworks that align with the evolving needs and dynamics of the context. Institutionalizing power also influences the design of governance structures because it requires transparency, inclusivity, and adaptability. Therefore, we argue that there is a mutually intertwined relationship between institutional trust and governance. Effective governance practices can contribute to the development and maintenance of institutional trust. On the other hand, the development of institutional trust increases the need for adopting new governance methods, as presented in Table 5. Consistent with (Autio, 2022), we contend that institutional governance plays a key role in organizing different layers within the ecosystem and sets a foundation for technical orchestration. According to Table 5, we argue that the governance of an open-source ecosystem is a dynamic process that changes based on the needs of the ecosystem. We demonstrated different governance systems within an ecosystem, ranging from a shared governance to a combined form in Table 5. The multitude of governance authorities and the need for more than one organization to take the lead in complex interorganizational networks to address wicked problems have been discussed by Kenis et al. (2019), by Sydow et al. (2022) in a study on managing reliability and responsibility, and by (Shaikh & Henfridsson, 2017) in a study on Linux foundation. Referring to these studies, we present a new hybrid governance model to organize open-source ecosystems comprising an ecosystem of an administrative organization comprising an independent catalyst and stakeholder representatives; in addition, an extended core periphery that consists of groups of organizations belonging to different organizational layers and subgroups is required. We argue that the core-periphery governance model proposed by Kenis et al. (2019) results in a fragmentation of layers in large-sized ecosystems that may threaten the sustainability of the ecosystem. Therefore, an extended core-periphery model supported by an administrative structure that facilitates coordination is a more appropriate governance strategy to connect the different layers. We argue that this combined strategy increases meritocracy, institutional trust, and power in the ecosystem.

ConclusionsThis longitudinal study on the evolution of an open-source ecosystem within a traditional industry illuminated a dynamic paradigm for understanding the governance of an open-source innovation ecosystem. Our findings emphasized the evolving interplay between trust and power at the individual, organizational, and institutional levels and the significance of this interplay in shaping the trajectory of open-source initiatives. We demonstrated that the institutionalization of power and trust creates a crucial framework that underpins ecosystem development, particularly within ecosystems characterized by high interdependencies and the recombination of diverse knowledge and technologies. Institutionalizing power in asymmetric power relations can encourage the generation of meritocratic ideas and reduce the exploitation of more minor actors. Our study emphasized the importance of institutional trust and power in complex ecosystems reliant on the proprietary knowledge of stakeholders. If participants trust the entire system's integrity, this ensures the accuracy and reliability of information and facilitates knowledge sharing and the reuse and recombination of shared knowledge.

This framework can serve as a tool for reflective practitioners. It can enable practitioners comprehend the significant aspects of the governance and managerial decision-making involved in fostering the establishment and expansion of an open-source innovation ecosystem and interorganizational collaboration. It can enable companies involved in open-source initiatives to design the appropriate governance system to address trust- and power- related issues. The institutional trust-building process has played a significant role in facilitating collaborations and contributions for further development of this innovative technology. This experience provides a valuable roadmap for other open-source initiatives to design organizational structures and adopt governance mechanisms that ensure meritocracy and create a trustworthy socio-technical ecosystem. In addition, the findings of this study regarding the role of an independent organization in organizing complex ecosystems and institutionalization processes also provide a foundation for technology adoption through licensing, facilitated by an independent catalyst.

This study has certain limitations, as it is challenging to devise a perfect research design focusing on open-innovation-based ecosystems (Remneland Wikhamn & Styhre, 2023). This approach will likely open up new opportunities to study this ecosystem with other methodologies. For example, future studies could use quantitative methods and theory testing to explore new factors on trust. The OSDU is an ongoing initiative and one that is constantly changing, and our study only covers the initial phases of this system. The new governance model has been recently developed; however, due to time constraints, we were unable to study the impact of the new model and its reinstitutionalization processes. We recommend that future research examine how this new governance model influences the institutionalization of trust and power within the ecosystem. It would be beneficial to study how the new governance strategy impact members’ contributions to the forum and collaboration.

Submission declarationThis article has not been published and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Data availability statementResearch data are not shared.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMahdis Moradi: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Vidar Hepsø: Conceptualization, Supervision, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Per Morten Schiefloe: Conceptualization, Supervision, Methodology.

This research was sponsored by the BRU21 – NTNU Research and Innovation Program on Digital and Automation Solutions for the Oil and Gas Industry (http://www.ntnu.edu/bru21). The sponsor was not involved in research design and data collection.

Mahdis Moradi is a PhD student in sociology at the department of sociology and political science at NTNU. Her research is about social aspects of digital transformation in the oil and gas industry. Her focus is on interplay of institutional trust and power dynamics in the development and adoption of a new data platform, Open Subsurface Data Universe, in the oil and gas industry.

Vidar Hepsø holds a PhD in social anthropology and is adjunct professor at the NTNU Research and Innovation Program on Digital and Automation Solutions for the Oil and Gas Industry. His main interests are related to new types of collaboration enabled by new information and communication technology (ICT) in general and in particular ICT-infrastructure development, capability platforms and collaboration technologies.

Per Morten Schiefloe is an emeritus professor of sociology at NTNU. His research work is particularly linked to two main fields: Organizational sociological issues within development and change, culture, innovation, and safety; network theoretical issues within the local environment, networks in organizations.