This study examines the influence of participative leadership and cultural factors on employees’ speaking-up behaviour and knowledge-sharing in supplier development initiatives in the garment industry. Specifically, this study investigates the impact of leadership effectiveness, cultural dimensions, and individual characteristics using surveys and interviews. Our findings indicate that participative leadership positively correlates with employee speaking-up behaviour. However, the analysis of variance (ANOVA) results show that language proficiency and region significantly influence employees’ willingness to speak up, although the differences in knowledge-sharing scores across cultural groups are statistically insignificant. Mediation analysis further reveals that perceived leadership effectiveness partially mediates the relationship between participatory leadership and knowledge-sharing intentions. The interview findings provide deeper insights into the roles of cultural intelligence, communication barriers, and social identity in shaping knowledge flow. These findings offer practical implications for organisations seeking to enhance supplier development initiatives. To foster an inclusive environment that empowers employee voice and encourages collaborative knowledge sharing, organisations can adopt participative leadership, accommodate cultural and linguistic diversity, and promote effective leadership perceptions. We anticipate that future research will explore the generalisability of these findings across industries and examine additional cultural dimensions that influence knowledge-sharing dynamics.

Global buyers have long been implicated in supplier development programmes in the Global South; the garment industry is particularly infamous for its performance (Bag et al., 2023; Vang et al., 2023). Compared to other industries, the garment industry offers a unique and valuable setting for examining supplier development owing to its intricate global supply chains and complex buyer–supplier dynamics requiring careful coordination and management (Gereffi et al., 2005). Supplier development programmes in the garment industry often involve joint buyer-supplier initiatives to improve quality, productivity, and sustainability. For example, buyers may provide training and resources to help suppliers upgrade their manufacturing processes, implement lean methodologies, or adopt eco-friendly practices (Hasle & Vang, 2021a). Unlike other industries, the garment industry's supply chain is highly fragmented; suppliers are often located in developing countries while buyers are in developed markets (Gereffi et al., 2005). This geographical and cultural distance exacerbates communication barriers and hinders effective knowledge transfer between supply chain partners (Anderson et al., 2023; Asamoah et al., 2023; Nurhayati et al., 2023). Moreover, the garment industry faces intense competition, fast-paced product cycles, and stringent quality and compliance requirements (Jia et al., 2023). Hence, conducting supplier development programmes in the garment industry is essential to ensure quality, ethics compliance, and sustainability standards (Hasle & Vang, 2021; Jia et al., 2023; Vang et al., 2023). Moreover, implementing effective supplier development initiatives, particularly joint development initiatives (Krause & Krause, 1997), will enhance supply chain performance and foster mutually beneficial buyer-supplier relationships (Fält-Ollikainen, 2018; Saghiri & Mirzabeiki, 2021).

The organisational behaviour literature has extensively examined speaking-up behaviour and the voluntary expression of ideas, concerns, or opinions in improving organisational performance (Bergeron & Thompson, 2020; Frazier, 2013; Tedone & Bruk-Lee, 2022). While its relevance and implications in the context of supplier development initiatives remain underexplored, facilitating successful buyer-supplier relationships requires open communication, knowledge sharing, and expression of concerns and suggestions (Giannakis, 2008; Modi & Mabert, 2007; Wiratmadja & Tahir, 2021). Speaking up highlights potential issues in buyer-supplier relationships, encourages collaborative problem-solving, and ensures continuous improvement efforts. Cultural factors and leadership dynamics significantly influence speaking up and knowledge sharing in supplier development contexts (Salimian et al., 2017, 2021). Specifically, cross-cultural differences in communication norms, power distance, and individualism-collectivism orientations influence employees’ willingness to express opinions and share information (Kwon & Farndale, 2020). Furthermore, leadership styles and perceived psychological safety within organisations are crucial in encouraging or discouraging speaking up and knowledge sharing (Edmondson & Lei, 2014), thereby impacting supplier development activities.

Previous studies (Benton Jr et al., 2020; Gu et al., 2021) have extensively investigated supplier development from operational (Sillanpää et al., 2015; Singh & Kumar, 2020) and strategic (Sillanpää et al., 2015) perspectives. However, the understanding of how soft factors influence organisational behaviours and employee dynamics is limited (Chi et al., 2024; Long, 2024). Furthermore, the role of speaking-up behaviour and its impact on knowledge sharing and collaborative buyer-supplier improvement efforts have received limited attention in the supplier development literature (Morrow et al., 2016; Tucker, 2012).

This study addresses this critical gap in the literature by examining the leadership and cultural dynamics in supplier development in Myanmar's garment industry through speaking-up behaviour and knowledge-sharing perspectives. Specifically, it examines the influence of participative leadership, cultural factors, and individual background on employees’ speaking-up behaviour and knowledge sharing. Myanmar's garment industry, serving as a central manufacturing hub, is crucial to global supply chains. However, it faces various challenges, including low productivity, inconsistent quality, long lead times, and limited adoption of sustainable practices (Govindan et al., 2021). These constraints have hindered the industry's ability to attract large international buyers and grow through exports (Hasle & Vang, 2021b).

This study integrates insights from the organisational behaviour literature on speaking-up behaviour and knowledge sharing with the supplier development literature. This comprehensive approach aims to identify the mechanisms that promote or obstruct open communication and knowledge sharing during supplier development initiatives. It explores speaking-up behaviour and its antecedents, including leadership styles, cultural norms, and perceived psychological safety. An understanding of these dynamics can help buyers and suppliers create an environment in which employees are encouraged to collaboratively share their concerns and expertise and identify improvement areas (Nagati & Rebolledo, 2013; Rashidi & Saen, 2018).

Moreover, this study addresses gaps in various literature streams. It introduces a novel perspective, emphasising the importance of soft factors, particularly speaking-up behaviour and knowledge sharing dynamics. This study integrates organisational behaviour concepts to comprehensively understand the complex interactions between buyer–supplier relationships, communication patterns, and continuous improvement efforts. Furthermore, this study recognises the potential impact of individual characteristics such as cultural background, language proficiency, and demographic factors on speaking-up behaviour and knowledge-sharing tendencies. These individual-level factors contribute to a deeper understanding of the complex interplay between organisational, cultural, and personal factors that influence supplier development practices. By integrating insights from the organisational behaviour and cross-cultural management literature, this study provides a more holistic understanding of the complex dynamics that shape communication and collaboration among garment workers and their supervisors.

The rest of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 presents the existing literature and hypotheses development. Section 3 describes the research methodology. Sections 4 and 5 detail the findings and discussion, respectively. Section 6 presents the conclusions, limitations, and directions for future research.

Literature reviewOrganisations’ pursuit of supplier development initiatives is critical for enhancing supply chain performance and capability (Krause et al., 2007; Krause & Krause, 1997). When effectively implemented, these initiatives can bolster supply chain competitiveness by reducing costs, improving delivery reliability, and enhancing product quality (Modi & Mabert, 2007). Research has focused on the operational and strategic aspects of supplier development; however, the understanding of the role of soft factors, such as organisational behaviour dynamics and cultural influences (Suurmond et al., 2020), is lacking. Supplier development involves the long-term cooperative effort between a firm and its suppliers to improve supplier quality and performance (Krause & Krause, 1997). Suppliers are evaluated as part of conventional supplier development strategies; their performance is measured and direct assistance on quality management, process improvement, and product development is provided (Krause & Ellram, 1997b, 1997a). However, the human and behavioural factors that significantly impact the effectiveness of supplier development initiatives are often overlooked.

The importance of knowledge sharing for organisational success has been well-documented in the literature. Recent studies have explored the role of leadership styles in encouraging knowledge-sharing behaviours among employees. For instance, Khatoon et al. (2024) found that empowering leadership, directly and indirectly, enhances employees’ knowledge sharing through psychological empowerment; this relationship is further strengthened by employees’ learning goal orientation (Khatoon et al., 2024). Chaudhary et al. (2023) examined the influence of paternalistic leadership, along with its benevolent, moral, and authoritarian dimensions, on nurses’ knowledge sharing, revealing that affective and normative organisational commitment mediate this relationship. Furthermore, work ethics moderate the link between organisational commitment and knowledge sharing (Chaudhary et al., 2023). Islam et al. (2024) explored how knowledge sharing facilitates innovative work behaviour; occupational self-efficacy mediates this relationship, while entrepreneurial leadership strengthens it (Islam et al., 2024). Islam and Asad (2024) found that entrepreneurial leadership enhances employee creativity. This relationship is explained by knowledge sharing, with creative self-efficacy moderating the association between knowledge-sharing and creativity association (Islam & Asad, 2024). Collectively, these studies highlight the complex interplay between leadership styles, organisational factors, individual characteristics, and knowledge-sharing dynamics, providing a valuable foundation for this study.

Knowledge sharing enhances organisational learning and continuous improvement (Argote et al., 2000; Argote & Ingram, 2000). Buyer–supplier knowledge sharing is vital for supplier development because it can facilitate the transfer of best practices, identify improvement areas, and promote collaborative problem resolution (Modi & Mabert, 2007). Several factors can hinder knowledge sharing in inter-organisational contexts, including lack of trust, divergent organisational cultures, and lack of effective communication (Easterby‐Smith et al., 2008). A deeper understanding of the facilitators and enablers of knowledge sharing, including leadership support, shared goals, and cultural compatibility, is required to overcome these obstacles (Khalfan et al., 2007). Leadership effectiveness influences organisational outcomes and employee behaviour (Yukl, 2012). A company's leaders’ perceptions of trustworthiness, willingness to receive feedback, and empowerment can affect employees’ motivation and confidence in speaking up and sharing knowledge (Detert & Burris, 2007; Srivastava et al., 2006). The influence of cultural factors on communication patterns, knowledge-sharing norms, and supplier development initiatives cannot be overstated (Lakemond et al., 2006). Cultural dimensions, such as power distance and individualism-collectivism, can influence employees’ willingness to voice their opinions and share information (Hofstede, 2011). The quality and extent of information exchange between buyers and suppliers may also be affected by individual characteristics such as region and language proficiency (Simpson & Power, 2005).

Speaking-up behaviour—the voluntary expression of ideas, concerns, or opinions to improve organisational performance—is a crucial aspect of organisational dynamics (Detert & Edmondson, 2011). This process encourages employees to voice their suggestions, concerns, or dissenting views on organisational practices or policies (Li et al., 2020). Several factors, including leadership style, organisational culture, and perceived psychological safety, influence speaking-up behaviour (Edmondson & Lei, 2014). For instance, participatory leadership encourages employees to contribute their input and opinions, fostering a culture of psychological safety and trust and increasing employees’ willingness to speak up (Detert & Burris, 2007). Furthermore, organisations that value employee contributions and promote open communication are more likely to encourage employee speaking-up behaviour (Milliken et al., 2003), leading to a more engaged and empowered workforce.

Hypotheses developmentIn this study, we examine the applicability of speaking-up behaviour and its antecedents in the unique context of supplier development to contribute to the literature on organisational behaviour. We explore how participatory leadership (H1) and employee perceptions of leadership effectiveness (H3) particularly influence speaking up and knowledge-sharing tendencies within a cross-organisational setting. It sheds light on the role of speaking-up behaviour in inter-organisational collaboration by expanding speaking-up behaviour beyond the traditional intra-organisational context.

We acknowledge that cultural factors significantly impact employee behaviour and organisational dynamics. Investigating the effect of cultural norms, such as speaking up and backgrounds (H2), and individual characteristics like region and language proficiency (H4), contributes to the cross-cultural management literature. It enhances the understanding of how cultural influences shape communication patterns, knowledge-sharing practices, and the effectiveness of supplier development initiatives in diverse cultural contexts. Furthermore, this study contributes to knowledge management and organisational learning by examining how speaking-up behaviour and knowledge sharing can facilitate continuous improvement and collaborative buyer–supplier learning. To promote mutual learning and improvement opportunities, this study explores the mechanisms through which cultural factors, leadership dynamics, and individual characteristics influence knowledge exchange and integration across organisational boundaries.

We propose a novel theoretical framework, drawing from the supplier development, organisational behaviour, and cross-cultural management literature. This framework offers a unique perspective on the interaction between leadership styles, cultural differences, and individual characteristics in shaping knowledge sharing and speaking-up behaviour within the context of supplier development initiatives.

Participatory leadership, which champions employee involvement in decision-making processes and values employees’ contributions, enhances employee commitment, motivation, and job satisfaction. This approach, rooted in the literature, posits that employees thrive when involved in decisions that impact their work (Magbity et al., 2020; Somech, 2005). This offers hope for organisations seeking to foster a culture of open communication and knowledge sharing. Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) theory suggests that leaders are responsible for establishing unique relationships with their followers; the quality of these relationships influence various workplace outcomes, including employee voice behaviour (Hasib et al., 2020; Omilion-Hodges et al., 2021). Leadership that encourages participation will likely foster high-quality LMX relationships characterised by trust, respect, and open communication, motivating employees to speak out without fear of negative consequences (Cheung & Wu, 2014). Speaking-up behaviour is more likely to occur when employees feel psychologically safe. In a psychologically safe workplace, participatory leaders value employee input, encourage open communication, and employ a non-punitive approach to mistakes and dissenting opinions (Detert & Edmondson, 2011). Additionally, social interactions are often motivated by the expectation that others will treat them favourably or that their actions will be reciprocated (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Several empirical studies have found that participatory leadership and employee speaking up are positively related (Bao et al., 2021; Sax & Torp, 2015; Tedone & Bruk-Lee, 2022). Detert and Burris (2007) demonstrated that open communication and employee involvement in decision-making are essential for fostering a psychologically safe workplace. Tangirala and Ramanujam (2008) discovered that employees are more likely to speak up if they perceive their leaders as open to their input and include employees in their decision-making processes. Managing employees using a participatory approach and rewarding their contributions creates a sense of obligation and reciprocity, increasing employees’ willingness to share their thoughts and concerns (Detert & Burris, 2007).

Moreover, participatory leadership can catalyse open communication and buyer–supplier knowledge sharing in the garment industry. It is instrumental in fostering collective problem solving in day-to-day operations by leveraging workers’ ideas and insights to improve operations. Open communication and knowledge sharing can lead buyers and suppliers to engage in collaborative problem solving, continuous improvement, and effective transfer of best practices across the supply chain, instilling confidence in the proposed framework.

Based on this discussion, we propose the following hypothesis.

H1: Participatory leadership positively influences employee speaking-up behaviour within garment factories.

Hofstede's cultural dimensions theory posits that cultural values and norms influence an individual's attitudes, behaviours, and communication. Knowledge-sharing behaviours within organisations are influenced by power distance, individualism-collectivism, and uncertainty avoidance (Suppiah & Singh Sandhu, 2011). For example, in high power distance cultures, employees may feel intimidated about challenging those in higher positions, thereby reducing their willingness to share knowledge (Michailova & Hutchings, 2006). Ardichvili et al. (2006) reported low knowledge sharing in virtual teams due to the cultural values of individualism and distance. Research has demonstrated that cultural factors influence knowledge sharing (Abili et al., 2011; Azeem et al., 2021; Setini et al., 2020; Vajjhala & Baghurst, 2014). For instance, knowledge sharing may be hindered in cultures emphasising individual achievement and competition (Ardichvili et al., 2006). Employees’ cultural backgrounds significantly influence supplier development. These cultural factors shape their perceived social identity and willingness to share knowledge with ‘outsiders’ or members of different cultural groups (Choi et al., 2023; Ipe, 2003; Usanova et al., 2023). This underscores the importance of understanding and addressing cultural differences in fostering effective knowledge sharing in supplier development initiatives.

A critical component of the knowledge governance approach involves recognising that several formal and informal factors such as organisational culture, norms, and values, including communication styles, trust levels, and shared values, influence knowledge sharing within and across organisations (Pemsel et al., 2016; Van Kerkhoff & Pilbeam, 2017). Specifically, these factors, which are informal governance mechanisms or unwritten rules guiding behaviour, support or impede knowledge sharing (Suppiah & Singh Sandhu, 2011). Employee behaviour and decisions are influenced by an organisation's shared values, beliefs, and norms (Bagga et al., 2023). A team culture encompassing shared values, norms, and practices, including openness, collaboration, and trust, facilitate knowledge sharing. Conversely, a team culture involving secrecy, competition, and suspicion inhibits it (D. W. De Long & Fahey, 2000).

Cultural factors significantly affect buyer–supplier knowledge sharing in the garment industry (Tran et al., 2023; Zare et al., 2023). Cultural differences in communication, trust levels, and values may hinder effective knowledge exchange and collaborative problem solving (Aslam et al., 2023; Zheng et al., 2024).)To facilitate supplier development initiatives, organisations must consider these cultural factors and develop strategies to bridge cultural gaps, foster shared understanding, and cultivate an environment conducive to open communication and knowledge sharing.

Based on this discussion, we propose the following hypothesis.

H2: Cultural factors significantly impact employee knowledge sharing within garment factories.

The central hypothesis of this study proposes that perceived leadership effectiveness mediates the relationship between participative leadership and employee knowledge-sharing behaviour. This is because influential leaders’ behaviours and actions positively influence various outcomes, including employee attitudes, motivation, and performance, in achieving organisational objectives. Specifically, employees are more likely to engage in positive behaviours such as knowledge sharing when they perceive their leaders as effective, trustworthy, and competent (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Srivastava et al., 2006), trusting that their contributions will be valued and appropriately utilised. This highlights the significant role that employee perceptions play in the knowledge-sharing process, empowering employees to contribute to the organisation's growth and success.

Previous research has demonstrated that perceived leadership effectiveness significantly mediates the relationship between leadership styles and knowledge-sharing behaviours (Connelly & Kevin Kelloway, 2003; Lin et al., 2020). Effective leaders foster an environment conducive to knowledge exchange by promoting trust, support, and open communication. Therefore, participative leadership practices alone may not directly lead to increased knowledge sharing. Instead, employees’ perceptions of whether their participative leaders are practical and capable of creating a psychologically safe environment are critical intervening mechanisms facilitating knowledge sharing during supplier development initiatives.

Based on this discussion, we propose the following hypothesis.

H3: Perceived leadership effectiveness mediates the relationship between participatory leadership and employee knowledge sharing.

Individuals adapt and function effectively in various situations because of their cultural intelligence and preferences (Thomas et al., 2015). Cultural intelligence comprises four dimensions: cognitive, metacognitive, motivational, and behavioural (Earley & Ang, 2003). A critical factor in individual adaptability in a cross-cultural context, cultural intelligence can significantly influence effective communication and knowledge sharing. Employees with high cultural intelligence tend to demonstrate effective communication and knowledge-sharing skills and better navigate cultural differences. In cross-cultural contexts, group identities may influence an individual's attitude, behaviour, communication style, and willingness to share information. Our hypothesis focuses on group-level variations based on regional or linguistic backgrounds, aligning more with functional heterogeneity rather than individual cultural intelligence. Functional heterogeneity posits that team or organisational diversity can enrich or hinder knowledge sharing and collaboration.

In Myanmar's garment industry, employees’ speaking-up behaviour and knowledge-sharing tendencies may vary according to their backgrounds such as region or language. Individuals’ comfort levels in expressing ideas, concerns, or expertise may vary depending on cultural norms, linguistic barriers, and regional differences, particularly in cross-cultural buyer–supplier interactions. Understanding these individualised factors helps organisations develop strategies for facilitating effective communication and knowledge sharing across diverse employee groups. Therefore, it may be necessary to provide language training, foster cultural intelligence, and establish inclusive environments that value diversity and promote knowledge sharing and collaboration while addressing potential barriers to collaboration.

Based on this discussion, we propose the following hypothesis.

H4: Employees from diverse backgrounds, such as different regions or language groups, exhibit variations in their speaking-up behaviour and knowledge-sharing tendencies.

To address the research questions, we conducted a case study on Myanmar's garment industry using intervention-based research. Myanmar's garment industry, characterised by diverse cultural backgrounds and buyer–supplier relationships, provides a rich foundation for our study. We utilised a mixed methods approach as it suits our research goals, allowing the integration of numerical data and in-depth insights to elucidate the phenomena under investigation. Quantitative surveys enabled the assessing of statistical relationships between the key variables—participative leadership, cultural groups, and communication/knowledge-sharing behaviours. Qualitative interviews were conducted to complement the quantitative data, offering deeper insights into the underlying mechanisms, contextual factors, and individual experiences influencing these dynamics. Using a mixed methods approach enabled us to gain a holistic and contextualised understanding of how soft factors, including leadership styles and cultural influences, affect supplier development initiatives and collaborative improvement efforts between buyers and suppliers. This comprehensive mixed methods design aligns with the study's aim of uncovering the complex interplay between organisational, cultural, and individual-level factors influencing open communication and knowledge exchange within Myanmar's garment industry.

We developed and pre-tested a structured questionnaire to collect data from employees involved in supplier development initiatives in Myanmar's garment industry. The questionnaire comprised reliable and validated scales measuring different variables, guaranteeing data accuracy. These variables include participatory leadership, speaking-up behaviour, knowledge sharing, perceived leadership effectiveness, cultural dimensions (such as power distance and individualism-collectivism), and demographic variables. The questionnaire was translated into relevant languages to ensure accurate responses and comprehension.

In the qualitative phase of the study, we conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews with several employees and leaders involved in supplier development initiatives. The interviews explored the nuances of leadership dynamics, cultural influences, influence of peers and leadership communication, engagement mechanisms, and individual experiences related to speaking-up behaviour and knowledge sharing. The interview questionnaire was based on initial observations made during the intervention in factories and the literature review. Before the actual interviews, we conducted a pilot test with five frontline workers to test their reflections in terms of language, concepts, and so on. The interview questionnaire was slightly updated thrice once responses to a particular question became saturated or further exploration was required. Frontline workers (sewing operators and helpers) and line supervisors/leaders from the sewing production line were interviewed, following a purposive sampling method (based on gender, rural/urban, migrant and non-migrant, and Burmese or non-Burmese ethnicity). All respondents were involved in supplier development activities. We aimed to observe/understand respondents’ experiences through their involvement in supplier development interventions. To minimise time constraints and reduce potential social desirability bias in the responses regarding supervisors or the factory, interviews were conducted over the phone, in Burmese, outside the factory on Saturday afternoons or Sundays. Interviews with line supervisors/leaders were conducted over a digital platform (Zoom or Viber). Additionally, to minimise gender and age disparities, interviews were conducted by two female research assistants whose ages were within the range of many respondents. Typically, each interview lasted between 45 and 90 min.

In the quantitative phase of the study, a purposive sampling technique was used to ensure adequate representation of employees from different cultural backgrounds, regions, and language groups. The survey was administered in person considering the target population's accessibility and preferences. Nugraha et al. (2022) documented that a professional data gathering service provides reliable access to high-quality data. Thus, a team of local consultants, trained by the researchers involved, distributed the pre-tested questionnaire; a total of 459 individuals were surveyed. The system distributed 520 questionnaires, of which 472 were returned; 13 were rejected as they lacked data. According to Krejcie and Morgan (1970), the required sample size for a population of 6585 production workers from 9 selected factories is 459; the returned responses exceeded the required sample size. Each response was assessed using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Table 1 displays the factors, subfactors, items, and sources.

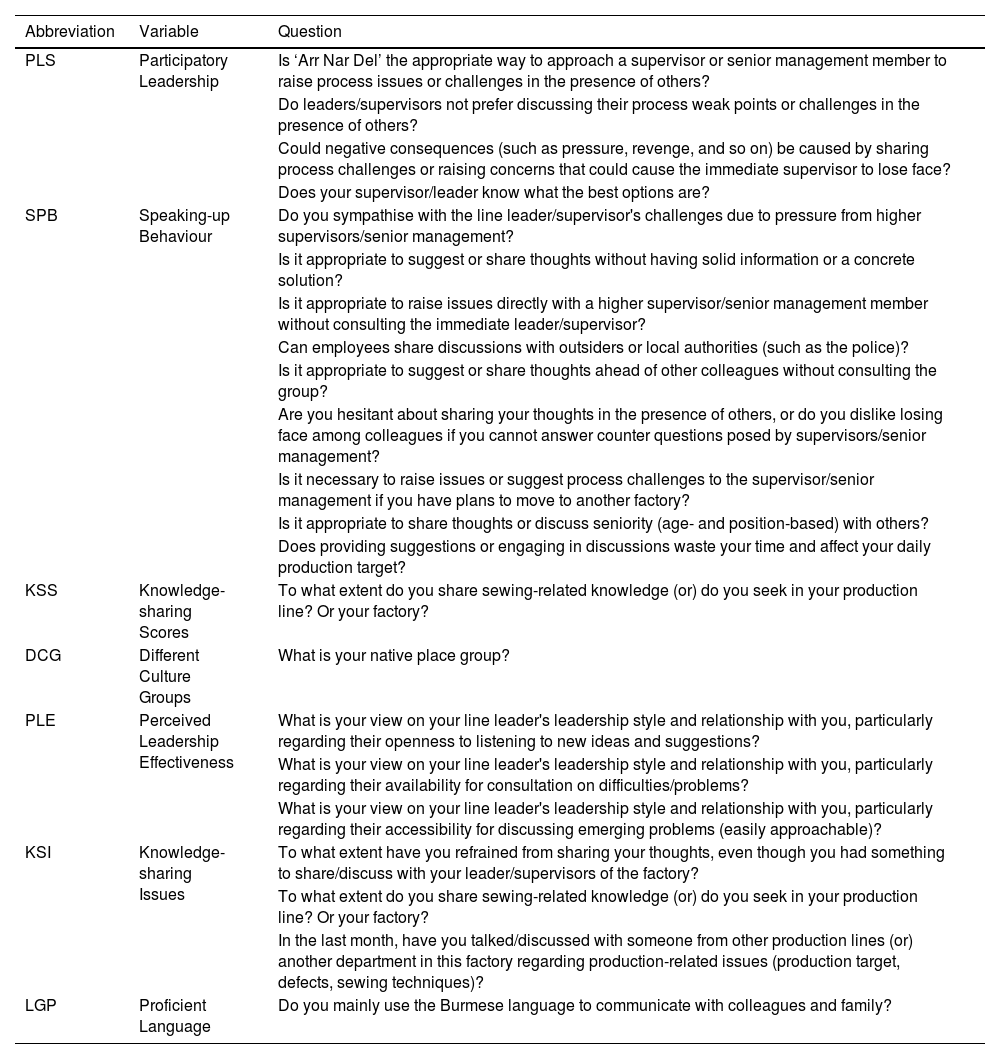

Constructs related to the questions.

We used regression analysis to test Hypothesis 1, while Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was employed to test Hypotheses 2 and 4. Mediation analysis was conducted to test Hypothesis 3, examining whether perceived leadership effectiveness mediates the relationship between participatory leadership and knowledge sharing.

The composition of the external teams (e.g. buyers and suppliers) involved in the supplier development initiatives was kept constant across all cases to isolate regional and linguistic diversity effects within the local teams. The external teams comprised individuals from the same cultural and linguistic background, thereby controlling for any potential variations introduced by diversity. This approach allowed us to examine regional and linguistic heterogeneity influences, specifically within the local teams, without confounding the effects of cultural differences from the external teams.

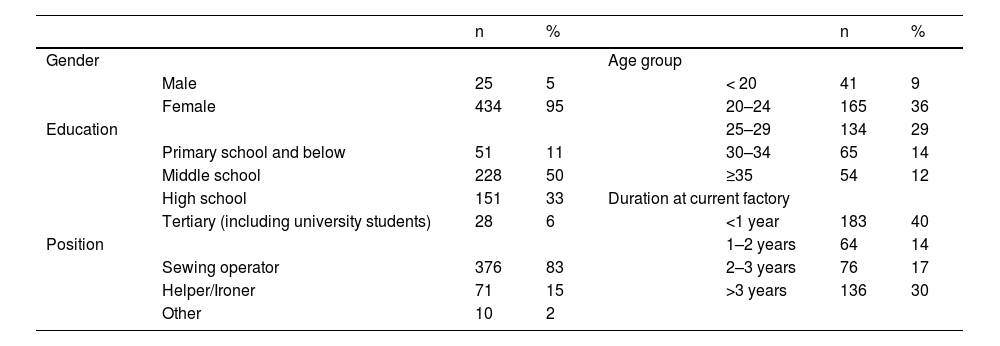

The survey design, which enabled the data collection team to follow up with the targeted respondents, primarily affected the survey's unbiased response rate. The quantitative data was triangulated with qualitative interviews (follow-up interviews, supplementary focus group interviews, and workshops) with 53 frontline workers (Nielsen et al., 2020). Table 2 presents the respondents’ demographic characteristics. Most respondents (40 %) had less than one year of work experience. Female operator responses (95 %) exceeded male responses.

Sample profile and respondents’ demographic information.

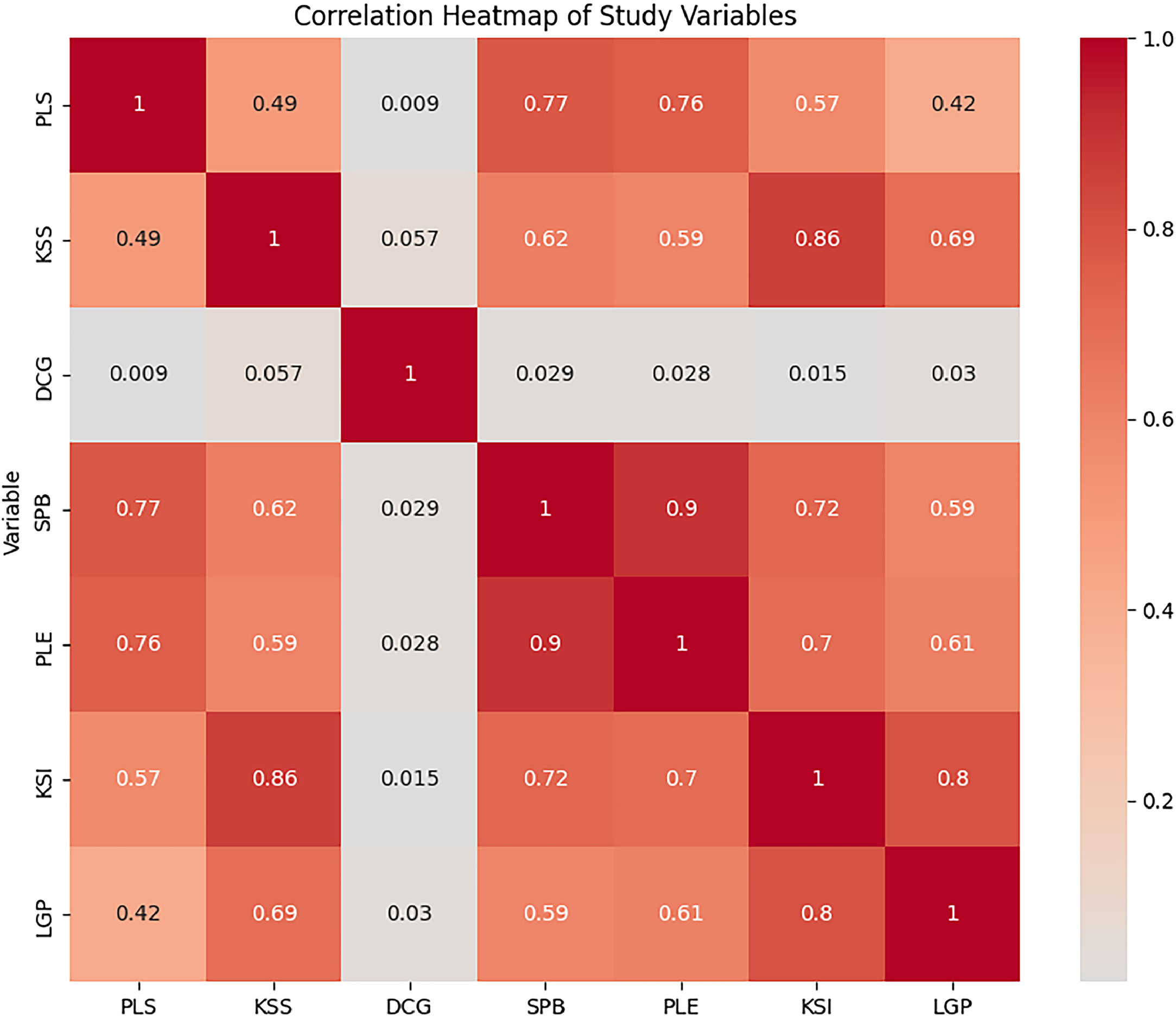

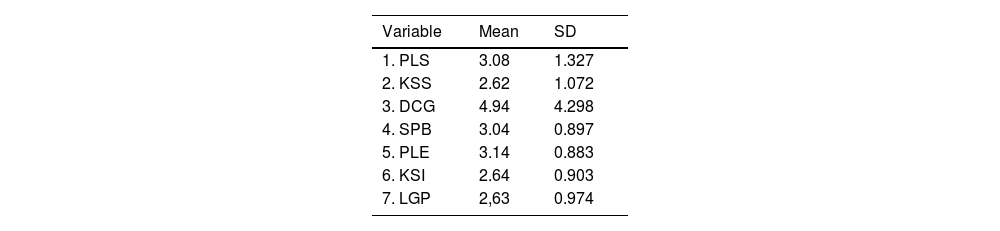

Table 3 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations among the study variables.

Table 3 and Fig. 1 reveal strong positive correlations between participatory leadership style (PLS) and speaking-up behaviour (SPB) (0.77), perceived leadership effectiveness (PLE) (0.76), and knowledge-sharing intention (KSI) (0.57). Similarly, knowledge-sharing score shows strong positive correlations with KSI (0.86) and moderate to strong positive correlations with SPB (0.62), PLE (0.59), and language proficiency (LGP) (0.69). Conversely, demographic/cultural group (DCG) exhibits very low correlations with other variables, suggesting that it may not significantly impact the other variables. This heatmap effectively highlights the key relationships, emphasising the strong associations between participatory leadership and knowledge-sharing-related behaviours and perceptions. The high correlation of 0.9 between PLE and SPB indicates potential multicollinearity concerns. To address this, we conducted additional diagnostic tests, including variance inflation factor (VIF), on the variables in the regression models. The VIF values were below the recommended threshold of five, suggesting that multicollinearity was not a significant issue in the analysis. The standard deviations of some variables such as DCG (4.298) and PLS (1.327) are relatively high compared to the mean values. This suggests a considerable spread in the data, which could be due to the sample's diverse cultural and demographic characteristics.

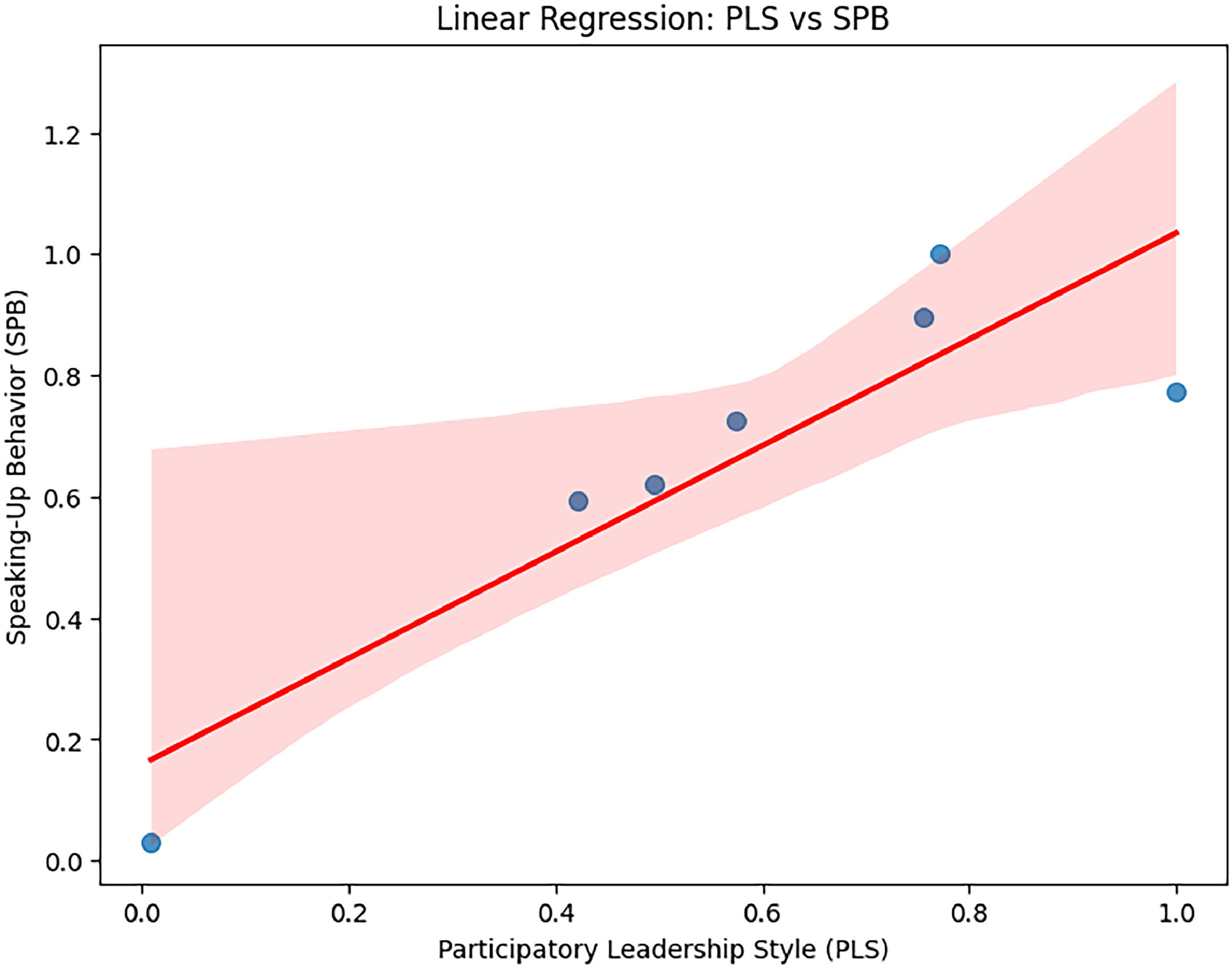

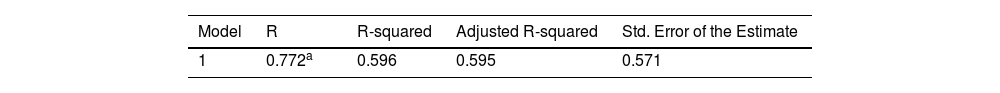

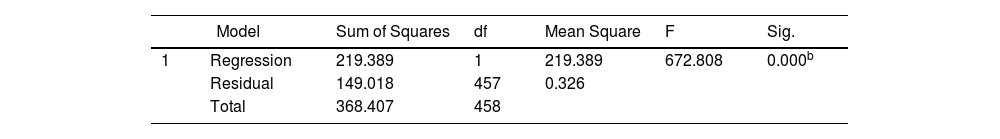

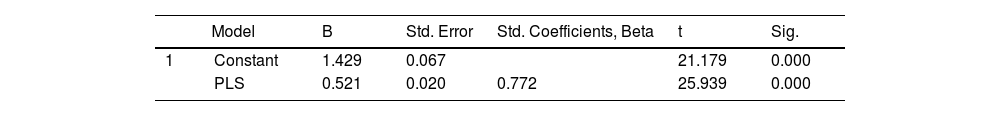

H1 was tested using linear regression analysis. The independent and dependent variables were PLS and SPB, respectively. The analysis also included control variables for employee demographics and organisational characteristics, although these variables are not specified in the output. The model summary (Table 4) provides an overview of the regression model's fit. The R-squared value of 0.596 indicates that 59.6 % of the variance in SPB is explained by the independent variable PLS; control variables are included in the model. However, other factors not included in the model may also contribute to the remaining variance. The ANOVA results (Table 5) assessed the overall significance of the regression model. The F-statistic of 672.808 with a p-value of 0.000 (less than the conventional significance level of 0.05) suggests that the regression model is statistically significant. This indicates that the independent (PLS) and control variables collectively and significantly influence the dependent variable (SPB).

Table 6 provides information on the individual predictors in the regression model. The unstandardised coefficient (B) for PLS is 0.521, with a standard error of 0.020. A standardised coefficient (beta) of 0.772 indicates that a one-unit increase in PLS is associated with a 0.772 standard deviation increase in SPB, holding all other variables constant. The t-statistic of 25.939 with a p-value of 0.000 (less than 0.05) for PLS suggests that the independent variable (PLS) has a statistically significant influence on the dependent variable (SPB), after controlling for other variables in the model.

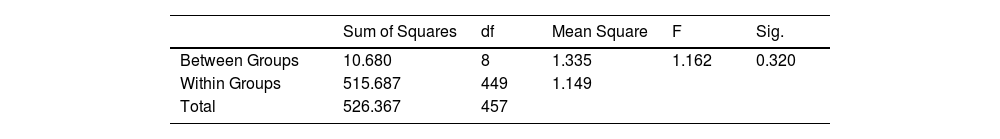

As shown in Fig. 2, the regression analysis results support H1, indicating that PLS significantly influences SPB among employees. The positive and statistically significant coefficient for PLS suggests that higher PLS levels are associated with increased SPB among employees. When interpreting these results, the study's context, measurement scales used, and any potential limitations or assumptions underlying the regression analysis should be considered. In summary, after controlling for employee demographics and organisational characteristics, the regression analysis supports the hypothesis that PLS positively influences SPB among employees in supplier development interventions.H2 was tested using ANOVA. ANOVA was used to compare the mean knowledge-sharing scores (KSS) across DCG. The ANOVA results presented in Table 7 show an F-statistic of 1.162 and a p-value of 0.320. As the p-value is more significant than the conventional significance level of 0.05, no statistically significant difference exists in the mean KSS scores among DCG.

The lack of statistically significant differences does not necessarily imply that cultural factors do not affect knowledge sharing. There could be other cultural dimensions or aspects not captured by the grouping variables used in the analysis. Additionally, the sample size within each cultural group may have been insufficient to detect significant differences. Interpreting these results should also consider the study's context, measurement scales used for knowledge sharing, and any potential limitations or assumptions underlying the ANOVA. In summary, the one-way ANOVA does not support the hypothesis that cultural factors significantly impact knowledge sharing among employees during supplier development interventions. However, further research and analysis are required to fully understand the relationship between cultural factors and knowledge sharing in this context.

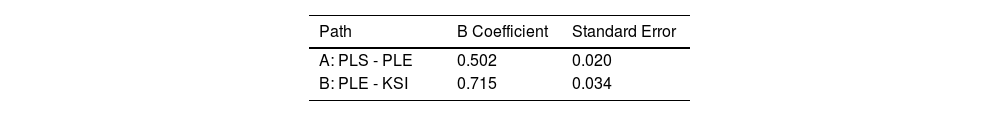

H3 was tested using mediation analysis, which estimated the mediating effect of PLE on the relationship between PLS and KSI. For this purpose, we used SPSS regression analysis and Sobel test. Details can be found in Baron and Kenny (1986), Sobel (1982), Goodman (1960), and MacKinnon et al. (1995).

The results of the two-stage regression analysis between PLS and PLE, and PLE and KSI are summarised in Table 8.

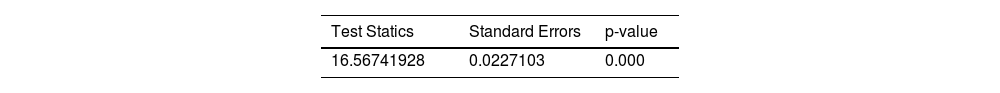

Using the B coefficients and standard errors in the online Sobel test, the critical ratio was calculated to test whether the indirect effect of PLS on KSI via the mediator is significantly different from zero. Table 9 presents the results of Sobel test.

The most important parameter here is the p-value, which is less than 0.05. Therefore, we can conclude that the indirect effect between PLS and KSI through PLE is statistically significant (p-value ≤ 0.05). To obtain the point estimate of the indirect effect at which the p-value in the Sobel test is statistically significant, we calculated the unstandardised beta coefficient: (0.502×0.715)=0.359.

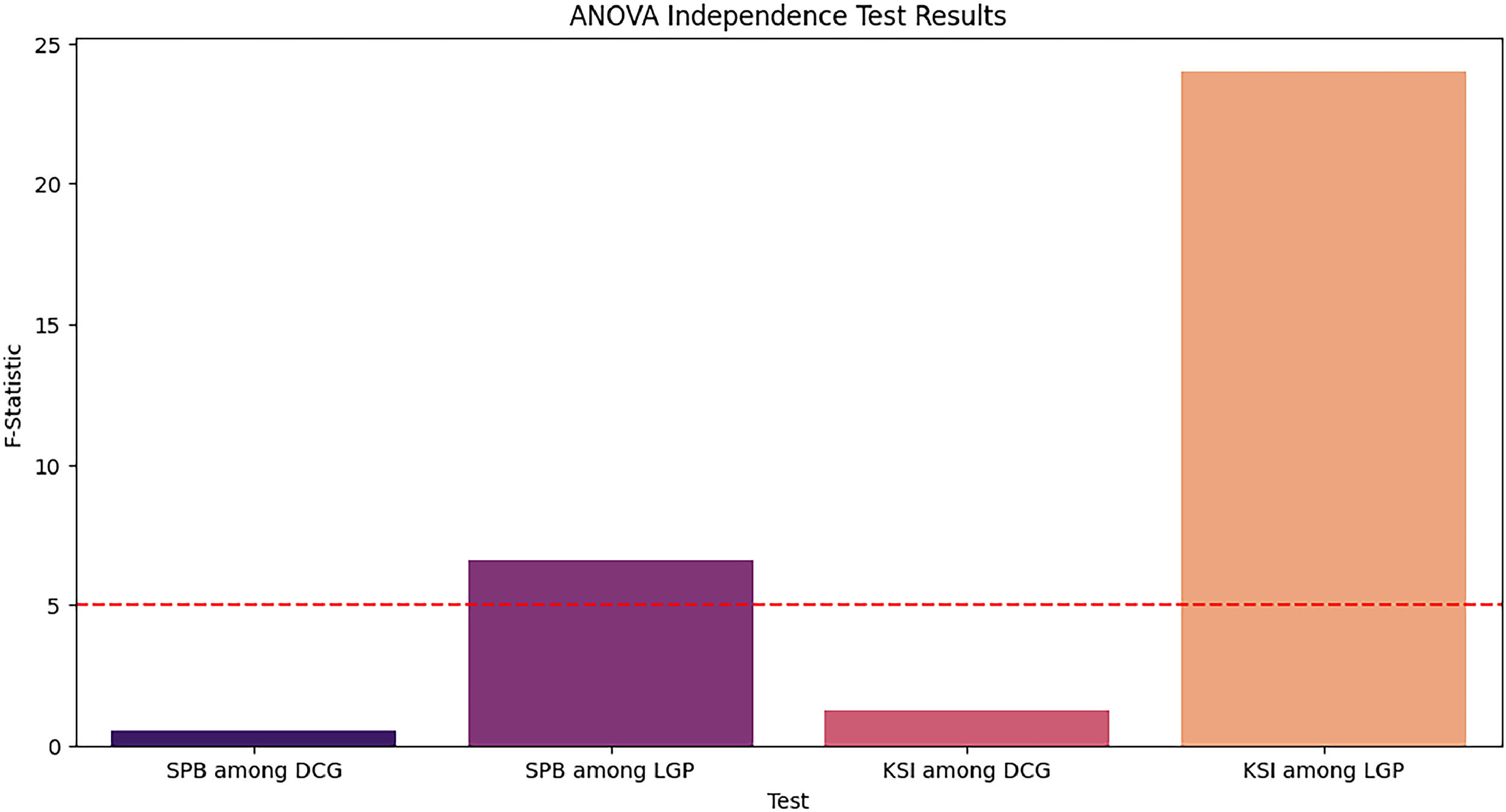

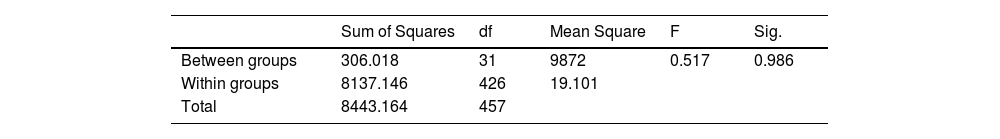

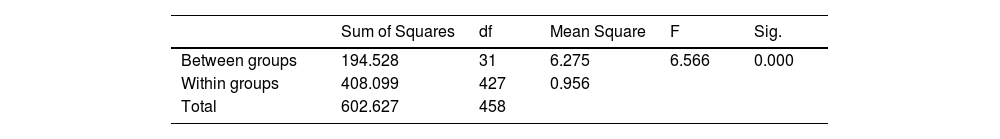

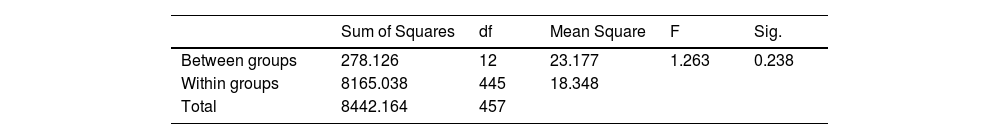

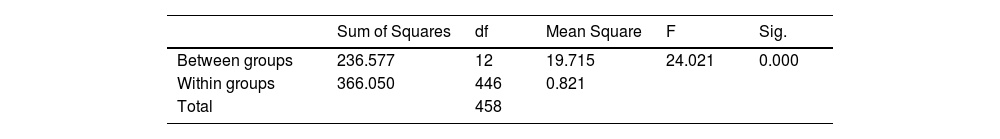

H4 was tested using ANOVA test of independence. Tables 10–13 show the ANOVA test of independence between the background characteristics, speaking-up behaviour, and knowledge-sharing tendencies.

As the p-values of SPB among DCG and KSI among DCG are greater than the conventional significance level of 0.05, no statistically significant association exists between region and SPB and KSI. The p-values in the tables show statistically significant associations between language proficiency and SPB and KSI.

Fig. 3 highlights the significant and non-significant associations between background characteristics and the dependent variables. The F-statistic values for each test are displayed; the dashed red line represents the conventional significance threshold (F = 5). Fig. 3 shows that the F-statistics for SPB among DCG and KSI among DCG are below the threshold, indicating no statistically significant differences in SPB and KSI across different cultural groups. In contrast, the F-statistics for SPB among LGP and KSI among LGP exceed the threshold, suggesting statistically significant differences in SPB and KSI based on language proficiency. This highlights that language proficiency significantly impacts both speaking-up behaviour and knowledge-sharing intention, whereas demographic or cultural group do not.

These findings suggest that employees’ background characteristics, specifically language proficiency, relate to their speaking-up behaviour and knowledge-sharing tendencies in supplier development interventions. Although the ANOVA tests indicated a significant association between the variables, they did not specify the strength or direction of the association. Furthermore, the interpretation of the results should consider the study's context, measurement scales used, and any potential limitations or assumptions underlying the ANOVA tests. These findings highlight the importance of considering individual background characteristics in fostering an inclusive and effective communication environment during supplier development initiatives.

DiscussionMany countries in the Global South, such as Myanmar, play a crucial role in global supply chains, often serving as suppliers or manufacturing hubs for industries like garment manufacturing. However, these nations face capacity constraints, knowledge gaps, and cross-cultural dynamics that hinder effective supplier development and knowledge transfer. Examining the interplay among leadership, culture, and individual factors in this context is particularly relevant. It informs strategies for empowering local workforces, overcoming communication barriers, and fostering an environment conducive to learning and collaboration. Understanding the nuances of speaking-up behaviours and knowledge sharing in the Global South can help organisations leverage their suppliers’ capabilities and facilitate mutual growth along the value chain. This study aims to offer insights to guide more inclusive and culturally intelligent approaches to supplier development in these regions. Several theoretical perspectives from the organisational behaviour and leadership literature support our finding that participatory leadership significantly influences employee speaking-up behaviour (Sax & Torp, 2015; Tedone & Bruk-Lee, 2022).

Embedded within leadership effectiveness, influential leaders inspire, motivate, and influence their followers to engage in behaviours aligning with organisational goals (House & Podsakoff, 2013). This finding provides a relevant framework for understanding the impact of participatory leadership on employee behaviours in this study's context.

Participatory leadership encourages employee involvement, collaboration, and open communication and is likely perceived an effective leadership approach (Cheung & Wu, 2014). When employees view their leaders as effective, they are not only more likely to feel empowered but also inspired and motivated to speak up, expressing their ideas and concerns (Li et al., 2020; Tedone & Bruk-Lee, 2022). This aligns with the observed positive relationship between participatory leadership and speaking-up behaviour. Social learning suggests that individuals learn by observing and modelling others’ behaviour, particularly those in positions of authority or influence (Guan et al., 2023). Participatory leaders, by actively soliciting input, attentively listening, and recognising employee contributions, serve as powerful role models for open communication and speaking up (Bagga et al., 2023). This underscores their influence on employee behaviours and organisational climate.

When leaders adopt a participatory approach during supplier development interventions, they cultivate an environment of trust and support for employees (Cheung & Wu, 2014). Participatory leaders signal that employees’ perspectives are valued by actively involving them and valuing their input. Consequently, employees may feel obligated to reciprocate by engaging in behaviours that benefit the organisation and strengthen the supplier–buyer relationship, such as proactively speaking up and sharing knowledge. In the context of supplier development initiatives, employees are more likely to voice their insights, concerns, and expertise when they perceive a supportive and inclusive climate fostered by participatory leadership (Bergeron & Thompson, 2020; Morrow et al., 2016). An open and psychologically safe environment encourages employees to contribute their perspectives, leading to improved collaboration, knowledge exchange, and buyer–supplier capability. This version clearly focuses on the study's context by explicitly linking leadership approach and employee reciprocation to supplier development intervention settings. It highlights how participatory leadership can foster employee speaking-up behaviour and knowledge sharing, strengthening the supplier–buyer relationship and facilitating mutual learning during these development programmes. When employees perceive a supportive and inclusive environment created by participatory leaders during supplier development initiatives, they are more likely to engage in voice behaviour, including speaking up (Bergeron & Thompson, 2020; Morrow et al., 2016).

A substantial portion of the variance in speaking-up behaviour explained by the regression model (59.6 %) is noteworthy, highlighting the significant impact of participatory leadership on fostering open communication and employee voice. However, other factors such as individual characteristics, team dynamics, and organisational culture may contribute to the remaining variance (Veldman et al., 2023). Overall, the theoretical foundations of leadership effectiveness and social exchange strongly support the observed positive relationship between participatory leadership and employee speaking-up behaviour in supplier development interventions. A participatory leadership approach fosters an environment in which employees feel empowered, supported, and motivated to speak up, contributing to effective collaboration and knowledge sharing during supplier development efforts (Lin et al., 2020).

The literature suggests that individuals learn by observing others in social contexts. In knowledge sharing, cultural factors influencing social interactions, such as communication norms and trust levels, significantly impact knowledge-sharing extent (I. G. Kwon & Suh, 2004; Rumjaun & Narod, 2020). If the ANOVA analysis did not yield statistically significant differences, it can be implied that the cultural factors examined do not strongly influence social learning processes related to knowledge sharing in this specific context. This concept posits that cultural differences are categorised into various dimensions such as individualism-collectivism, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance. However, this also suggests that the influence of these dimensions is more nuanced and complex than initially assumed. Organisational culture encompasses shared values, beliefs, and norms (Chatman & O'Reilly, 2016). This study included cases from multiple organisations participating in supplier development interventions, each with distinct organisational cultures. The specific organisational culture of the companies involved may exert a more significant impact on employees’ knowledge-sharing behaviours during the interventions than broader cultural factors at the national or regional level (Subramaniam et al., 2020). If so, the lack of significant differences in knowledge-sharing behaviour across different cultural groups suggests that organisational culture is more dominant in shaping knowledge-sharing practices than national or ethnic culture. Therefore, considering contextual factors to better understand employees’ behaviour is crucial. If our analysis did not find significant differences in knowledge-sharing behaviour across cultural groups, this could imply that the perceived benefits and costs of knowledge sharing are relatively consistent across cultures participating in supplier development interventions.

The analysis of the third hypothesis yielded significant results, indicating that perceived leadership effectiveness partially mediates the relationship between participatory leadership and knowledge-sharing intentions. This finding aligns with social exchange theory which posits that individuals engage in social exchanges based on the expectation of reciprocal benefits. Participatory leadership leads to positive perceived leadership effectiveness by fostering an environment of empowerment and value. This encourages employees to reciprocate by sharing their knowledge. The mediation analysis further suggests that perceived leadership effectiveness acts as a mechanism through which participatory leadership influences knowledge-sharing intentions. This underscores the transformative power of leadership in inspiring and motivating followers to enhance their performance (Asada et al., 2021). Participatory leadership involves employees in decision-making processes and aligns with the principles of transformational leadership. Employees perceive participatory leaders as effective because they provide opportunities for autonomy, involvement, and skill development (Bagga et al., 2023; Hasib et al., 2020). This positive perceived leadership effectiveness encourages employees to engage in knowledge-sharing behaviour. Participatory leadership significantly creates a social learning environment in which knowledge sharing is encouraged and valued. When employees perceive their leaders as effective in facilitating participation and collaboration, they are likely to emulate these behaviours and share their knowledge with others. This underscores the cognitive mechanism through which participatory leadership influences knowledge-sharing intentions, as individuals model their behaviour after influential leaders. In summary, the results of the third hypothesis align with theoretical perspectives emphasising the importance of leadership effectiveness in shaping employee behaviours such as knowledge sharing (Detert & Burris, 2007; House & Podsakoff, 2013). By fostering perceived leadership effectiveness, participatory leadership indirectly influences knowledge-sharing intentions through social exchange and learning mechanisms (Suppiah & Singh Sandhu, 2011; Usmanova et al., 2021).

The results of the fourth hypothesis, supporting the idea that employees from diverse backgrounds exhibit varying speaking-up behaviour and knowledge-sharing tendencies, align with several theoretical perspectives. Notably, social identity theory, a cornerstone of our theoretical framework, suggests that individuals’ self-concepts are shaped by their membership in social groups, such as language groups (Kassis-Henderson & Cohen, 2020). This finding provides a rich understanding of workplace dynamics. Employees may identify more strongly with individuals from their language group, leading to differences in communication behaviours. In the context of supplier development interventions, employees from different language groups tend to feel more comfortable speaking up and sharing knowledge with those from similar backgrounds. This is due to their perceived commonalities and shared experiences (Ganguly et al., 2020).

Consequently, variations in speaking-up behaviour are based on language proficiency, emphasising the influence of group membership on individual behaviour. Therefore, variations in speaking-up behaviour based on language proficiency are attributed to communication accommodation processes, wherein individuals tailor their communication strategies to suit their social context. In summary, the ANOVA test results, a crucial part of our study, empirically support the hypothesis that employees from diverse backgrounds exhibit variations in their speaking-up behaviour and knowledge-sharing tendencies during supplier development interventions.

Managerial implicationsOur findings carry significant managerial implications for the garment industry, aiming to foster effective communication, knowledge sharing, and employee engagement in supplier development interventions.

First, the positive influence of participatory leadership on speaking-up behaviour underscores the importance of leadership styles in creating an open and inclusive communication environment. Managers should adopt participatory leadership approaches that involve employees in decision-making, encourage active participation, and value diverse perspectives. By doing so, managers empower employees to voice their ideas and concerns, leading to increased engagement, innovation, and problem solving in supplier development initiatives.

Second, identifying variations in speaking-up behaviour based on employee backgrounds, such as region and language proficiency, highlights the need for managers to recognise and accommodate cultural and linguistic diversity within their teams. Managers should promote cultural sensitivity and inclusivity to ensure that all employees feel valued and respected, regardless of their backgrounds. Language support and communication training for employees with varying proficiency levels facilitate effective communication and collaboration across diverse teams.

Third, the partial mediation of perceived leadership effectiveness in the relationship between participatory leadership and knowledge-sharing intentions suggests that managers should promote participatory leadership behaviours and enhance employees’ perceived leadership effectiveness. Managers should communicate clear expectations, provide feedback, recognise employees’ contributions, and demonstrate a commitment to supporting knowledge-sharing initiatives. By fostering positive perceived leadership effectiveness, managers reinforce employee motivation to share knowledge and expertise, ultimately contributing to the success of supplier development interventions.

Overall, this study offers practical implications for garment industry leaders seeking to enhance intra-organisational communication, knowledge sharing, and collaboration among employees. By adopting participative leadership, accommodating cultural and linguistic diversity, and promoting perceived effective leadership, managers create an environment in which employees’ voices are empowered and knowledge is shared collaboratively to address operational challenges and drive organisational success.

Limitations and future research directionsWhile the study's findings provide valuable insights into the relationship between leadership, cultural dynamics, speaking-up behaviour, and knowledge sharing in the garment industry, several limitations must be acknowledged and avenues for future research should be explored. First, the study focuses on a specific industry—garment manufacturing—limiting the generalisability of the findings. Future research could extend this investigation to different industries to determine whether similar patterns of leadership effectiveness, cultural influences, and speaking-up behaviour emerge across diverse organisational contexts. Additionally, this study examines how participative leadership, cultural factors, and individual background characteristics affect employees’ speaking-up behaviour and knowledge sharing within supplier development initiatives in the Myanmar garment industry. While Myanmar represents a critical context within the Global South, our findings may not necessarily be generalisable to various nations and industries in the Global South. Myanmar's unique socioeconomic, political, and cultural characteristics may limit the transferability of the results to other developing regions. Future research examining similar dynamics across a broader geographic scope within the Global South is needed to enhance the external validity of the findings and provide a more comprehensive understanding of these phenomena in different developing countries.

Second, while the study identified significant associations among participatory leadership, cultural background, and speaking-up behaviour, the cross-sectional nature of the research design precludes causal inference. Longitudinal or experimental studies can elucidate the causal relationships between leadership styles, cultural dynamics, and communication behaviours over time. Moreover, the study focused primarily on speaking-up behaviour and knowledge-sharing intentions, neglecting other dimensions of communication effectiveness, such as listening skills, feedback receptivity, and conflict resolution strategies. Future research could adopt broader communication dynamics within supplier development interventions, exploring how various leadership styles and cultural factors influence communication effectiveness and organisational outcomes. Additionally, the study examined individual-level factors influencing speaking-up behaviour and knowledge sharing, overlooking potential contextual factors such as organisational culture, team dynamics, and leadership support structures. Future research could investigate the interplay between individual and organisational factors in shaping communication behaviours within supplier development initiatives, thus providing a more holistic understanding of the complex dynamics at play.

Contributions and implicationsThis study makes significant theoretical contributions to supplier development, organisational behaviour, and cross-cultural management by integrating insights from these diverse literature streams. This will further our understanding of the complex interplay among leadership dynamics, cultural influences, and individual factors in shaping speaking-up behaviour and knowledge-sharing practices within the context of supplier development initiatives. Practically, the findings of this study inform strategies for enhancing supplier development programmes and fostering more effective buyer–supplier relationships. Organisations design and implement supplier development initiatives that promote open communication, knowledge sharing, and continuous improvement by highlighting the importance of soft factors such as leadership styles, cultural considerations, and individual characteristics.

Furthermore, this research paves the way for future studies to explore other organisational behaviour concepts and their applications in supplier development and supply chain management, ultimately contributing to the development of more holistic and human-centric approaches to supply chain collaboration and performance improvement.

ConclusionsThis study sheds light on the intricate interplay among leadership styles, cultural dynamics, and individual background characteristics in shaping speaking-up behaviour and knowledge-sharing tendencies within the garment industry during supplier development interventions. The findings underscore the significant positive influence of participatory leadership on employees’ willingness to speak up, highlighting the importance of inclusive leadership practices in fostering open communication climates. Moreover, while we did not find statistically significant differences in knowledge-sharing scores across cultural groups, the associations among employees’ region, language proficiency, and speaking-up behaviour emphasise the nuanced impact of individual background characteristics on communication behaviours. The mediation analysis further elucidates the crucial role of perceived leadership effectiveness as a mechanism through which participatory leadership influences knowledge-sharing intentions, underscoring the importance of leaders’ abilities in inspiring employee confidence and trust.

Given its theoretical depth and practical relevance, this study offers valuable implications for organisations. It provides a roadmap for enhancing communication and knowledge sharing within supplier development initiatives. By adopting participatory leadership approaches, organisations can empower employees to voice their ideas and concerns, fostering collaboration and innovation. Additionally, organisations can effectively mitigate communication challenges and promote inclusivity by addressing cultural barriers and promoting cultural intelligence among leaders and employees. Ultimately, organisations can optimise supplier development interventions by understanding and leveraging the complex interplay between leadership, culture, and individual backgrounds. This, in turn, drives sustainable growth and success in the garment industry and beyond.

CRediT authorship contribution statementSeyed Pendar Toufighi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Iman Ghasemian Sahebi: Writing – original draft, Validation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Kannan Govindan: Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Investigation. Min Zar Ni Lin: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. Jan Vang: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Annalisa Brambini: Writing – review & editing, Visualization.

The research project behind the paper was funded by the DANIDA Danish Fellowship Centre (Project ID: Project no 19-M08-SDU; Overcoming barriers to improving OHS among SMEs in Myanmar). There are no conflicts of interest pertaining to the paper. The effort made by the Myanmar ESAM team to engage in data collection is recognized. The researchers also appreciate the collaboration of the local suppliers, global buyers, and employees at the factories. The project did not entail any collaboration with the Myanmar government.