The automobile industry's transition toward sustainability remains impeded by inconsistent green governance, which hampers progress in hybrid vehicle production. Existing literature predominantly focuses on technological innovation and consumer adoption, often overlooking the governance structures that foster environmental responsibility. This study proposes a framework of green governance strategy (GGS) designed to drive automakers’ proactive engagement in hybrid vehicle development. Grounded in social identity theory, our research challenges traditional perspectives on green innovation within the automobile industry. It highlights that companies with robust GGS act as pivotal drivers of hybrid vehicle development. Contrary to prior studies that relegated green products to a peripheral status, our findings position hybrid vehicles as central to corporate identity, integrating environmental responsibility with long-term profitability and alignment with sustainable development goals (SDGs). The study further reveals that despite economic pressures such as rising electricity costs, companies committed to GGS continue to prioritize hybrid vehicle production as a critical strategy to enhance sustainability performance and secure recognition in sustainability awards. However, a significant gap persists: 60 % of surveyed companies fail to address SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), while 55 % neglect SDG 13 (Climate Action). This misalignment emphasizes the need for more comprehensive goal integration across the sector. The findings provide valuable insights for scholars, policymakers, and industry standard-setters, offering guidance for developing future governance frameworks that support more holistic contributions to sustainable urban and climate goals.

Over the last decade, research has explored the relationship between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and technological innovation in promoting economic and social progress through technological advancements (Dey et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2024). Despite growing interest in sustainable business practices, the transition to eco-friendly materials and the development of hybrid vehicles in the automobile sector remain underexplored areas, particularly concerning their contributions to long-term economic sustainability and social responsibility (Kim, 2023; Schillebeeckx et al., 2022). Developing innovative vehicles that offer genuine, long-term benefits to humanity poses a significant challenge for automakers (Plantec et al., 2023). As Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla, aptly noted: “Those who have not actually been involved in manufacturing just have no idea how painful and difficult it is. It's like you got to eat a lot of glass.” (Carmine, 2021).

Amid escalating global issues such as climate change, pollution, and energy shortages, sustainable vehicles are critical for advancing a low-carbon economy and achieving a net-zero future (Bellocchi et al., 2019). The United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the International Council of Moter Vehicle Manufacturers, 2023 roadmap for decarbonizing road transport highlight the urgency of adopting zero-emission vehicles to meet global climate targets (International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers, 2023; Helfaya & Bui, 2022; Helfaya et al., 2023a; Stephanie et al., 2021).

The automobile industry also holds substantial economic significance, employing over 50 million people worldwide (International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers, 2023). In the post-COVID-19 era, the industry faces heightened environmental challenges, particularly concerning the emissions associated with in electric vehicle batteries (Li, Xia & Guo, 2022). This context amplifies the need for environmentally friendly vehicles and innovative GGS to enable responsible innovation without undermining profitability. Notably, economic growth is closely tied to rising electricity consumption, which directly affects corporate budgeting and competitive advantages.

While the adoption of electric and hybrid vehicles is increasing, research on sustainable business practices often lacks a concentrated focus on the governance mechanisms that drive these innovations toward sustainability performance (e.g., Raj et al., 2023; De Souza et al., 2018). Investments in hybrid vehicle development require substantial resources and commitment, yet there is limited understanding of how such investments align with corporate strategies to foster sustainable development. Moreover, prior studies have predominantly examined the motivations behind eco-friendly initiatives rather than their direct impact on corporate strategies and sustainable performance outcomes (see Kumar et al., 2024; Mora et al., 2023).

Although social identity theory has been utilized to explore sustainable development, its application in understanding the potential of sustainable vehicles to drive corporate sustainability strategies remains limited. Existing literature suggests the need to investigate how GGS can shape corporate identity and stakeholder perceptions, enabling companies to effectively communicate their societal and environmental contributions (Hawn & Ioannou, 2016; Madzík et al., 2024).

In response, this study aims to contribute to the growing body of literature on GGS and sustainability performance in the context of product innovation. Specifically, it examines the role of green governance mechanisms in supporting hybrid vehicle production, investigating whether these mechanisms facilitate sustainable practices and align with long-term environmental goals. Furthermore, the study explores the extent to which hybrid vehicle production contributes to sustainability performance, assessing whether such innovations provide both competitive and environmental benefits. By applying social identity theory, the study also seeks to understand how corporations can manage their corporate identity and optimize stakeholder engagement, leveraging GGS to foster positive perceptions and contribute effectively to the SDGs.

Accordingly, this study addresses two main research questions (RQ):

RQ1

Does green governance strategy promote the production of hybrid vehicles?

RQ2

Does the production of hybrid vehicles lead to sustainability performance?

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next section reviews previous studies to establish the theoretical and methodological foundation for examining the complex relationships among the variables. Section 3 details the research methodology. Section 4 presents the empirical results, and Section 5 discusses the findings and concludes the study.

Literature reviewGreen governance strategy and corporate environmental responsibilityWith growing global concern over environmental issues, corporate environmental impact has become a central focus for stakeholders, prompting the need for effective GGS within industries, particularly those with significant ecological footprints, such as the automobile sector (Romero-Castro et al., 2022). Scholars have highlighted the essential role of corporate governance in guiding environmental practices, yet a cohesive and practical framework for implementing GGS is still emerging (e.g., Aguilera et al., 2021; Bui & Nguyen, 2024; Helfaya & Moussa, 2017; Moussa et al., 2022). GGS enables organizations to adopt environmentally responsible practices, including reducing waste, utilizing renewable materials, and integrating environmental considerations into strategic planning (Barnett et al., 2020; Kumar et al., 2024).

The evolution of GGS traces back to early conceptualizations of proactive corporate environmental strategies. For instance, Murphy and Poist (2000) emphasized reducing resource consumption, reusing materials, and incorporating recycled inputs. Over time, GGS has expanded to include investment in green technologies and renewable energy (Eyraud et al., 2013). These foundational perspectives highlight that GGS transcends mere regulatory compliance, emphasizing the active embedding of environmental principles within corporate operations.

In the automobile sector, the proactive implementation of GGS is particularly relevant. As demand for sustainable transportation grows, the industry faces mounting pressure to mitigate the ecological footprint associated with vehicle manufacturing and usage. In this context, GGS includes minimizing waste through recycling, enhancing fuel efficiency, and reducing emissions. Despite empirical evidence supporting the positive impact of GGS, two critical gaps persist. First, GGS should originate from a corporate philosophy ("inside-out" approach) rather than as a reaction to societal demands (Crilly & Sloan, 2012). For instance, Heinkel et al. (2001) demonstrated that companies are more likely to adopt ethical practices when a substantial portion of their investors prioritize green values, highlighting the importance of rooting sustainable practices within corporate identity. Second, successful GGS implementation must begin with a robust corporate governance mechanism to establish a foundation for long-term environmental strategies (see Helfaya et al., 2023b; Holland et al., 2024; Mora et al., 2023).

Building on these insights, our study defines a proactive set of green governance dimensions comprising five primary initiatives: green capital expenditure (capex) targets, green revenue targets, environmental partnerships, climate-related risk assessment processes, and environmental management teams.

Social identity theory, hybrid vehicles and sustainability performanceSocial identity theory, originating from Tajfel's work, examines how individuals define themselves based on group memberships, influencing their social values and behaviors (Hornsey, 2008). This theory has been extended to corporate sustainability contexts. For example, Umrani et al. (2022) argued that organizations can leverage social identity theory to shape a corporate identity aligned with stakeholder values, fostering trust, loyalty, and positive perceptions. In this context, hybrid vehicles symbolize the corporate commitment to sustainability, reinforcing an organization's dedication to environmentally friendly practices. As social groups increasingly advocate for eco-friendly mobility, hybrid vehicles serve not only as products but as representations of corporate sustainability identity (Stets & Burke, 2000). Adopting such vehicles aligns companies with the values of environmentally conscious stakeholders, fostering harmony, credibility, and positive reputations within communities (Helfaya et al., 2018; Lii & Lee, 2012).

Despite existing research on corporate identity and CSR, the relationship between social identity, hybrid vehicles, and sustainability remains underexplored. Few studies have examined how motivations behind CSR influence corporate behavior, such as hybrid vehicle production, or how these efforts impact stakeholder perceptions (e.g., Helfaya et al., 2023a; Madzík et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2023). Social identity theory posits that establishing a corporate identity aligned with sustainability values enhances appeal to eco-conscious stakeholders, creating strong incentives for automakers to pursue GGS and sustainable practices.

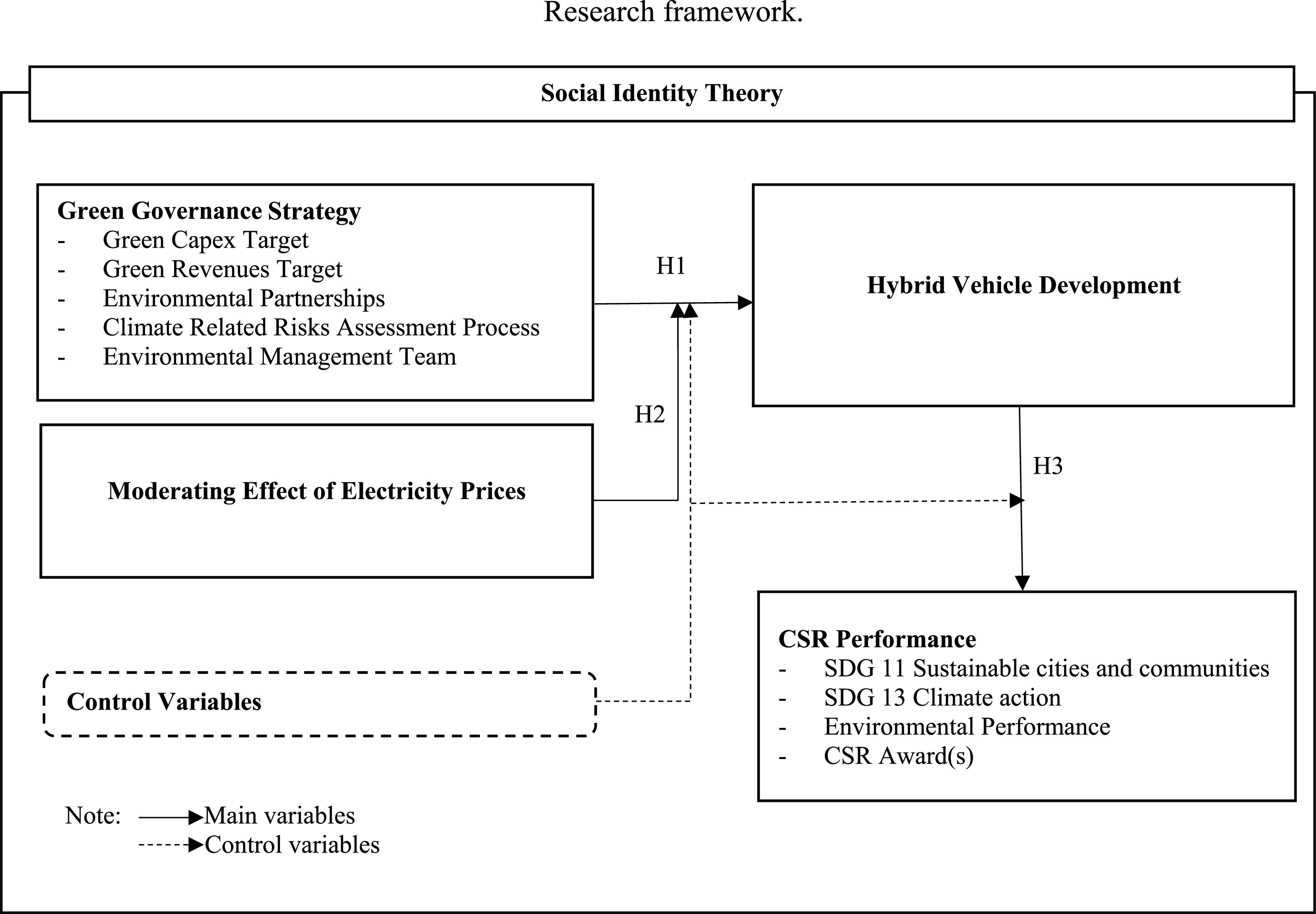

Thus, this study claims that two key factors drive corporate engagement in CSR and sustainable mobility initiatives (as shown in Fig. 1). First, companies must develop an awareness of their competitive standing to differentiate themselves through sustainable practices. Second, they must cultivate a unique "green" identity that resonates with stakeholders and reflects long-term environmental responsibility. Together, these factors incentivize automakers to adopt GGS, enhancing their competitive advantage and social capital in an increasingly eco-conscious marketplace.

Hypotheses developmentGreen governance strategy and hybrid vehicle developmentGreen practices mitigate environmental impact by improving corporate carbon performance, promoting sustainable mobility, and advancing a zero-carbon energy future (Bartnik et al., 2018; Kumar et al., 2024). Hybrid vehicle development aligns with these objectives, yet inconsistencies remain in defining GGS across industries and corporate structures. While GGS is recognized as a driver of corporate investment in green technologies for SDGs (Guo et al., 2020; Han et al., 2024), and green product innovation (Bartnik et al., 2018; Lyulyov et al., 2024). Further research is needed to explore their relationship with other strategic environmental approaches. Moreover, companies that adopt green practices experience reduced pressure to demonstrate their legitimacy and are more inclined to invest in green products, provided the anticipated benefits outweigh the costs (Helfaya et al., 2023b; Helfaya & Whittington, 2019; Kumar et al., 2024). A rational motivation is essential for such investments, as it enables companies to gain a competitive edge by effectively communicating the advantages of implementing and promoting GGS to stakeholders.

From a social identity perspective, corporate identity fosters a sense of belonging within environmentally conscious groups, encouraging companies to invest in hybrid vehicles as a tangible commitment to a zero-carbon economy (Rashidi-Sabet et al., 2022). Research rooted in social identity theory indicates that businesses prioritize fostering a positive social identity within their group rather than engaging in exclusionary practices (Abrams & Hogg, 1988). Recent studies also reveal a positive correlation between the implementation of GGS and investments in high-tech innovations (e.g., Li et al., 2016). Furthermore, social identity theory highlights the role of peer influence in shaping corporate identities and behaviors (Postmes et al., 2005; Turner, 1975). For example, as more automobile companies adopt green strategies, the pressure on others to follow suit increases, as maintaining a favorable standing among peers becomes critical. The necessity for companies with significant green investments to produce hybrid vehicles is further amplified, as these vehicles serve as tangible evidence of their commitment to environmental sustainability. Drawing from this discussion, we posit that GGS can catalyze hybrid vehicle production by supporting the establishment of a socially responsible corporate identity, aligning with stakeholder values, and ensuring competitiveness in an increasingly eco-conscious marketplace. Consequently, our first hypothesis is established, as follows:

H1

The greener the investment strategy, the higher the likelihood of automobile companies manufacturing hybrid vehicles.

The moderating effect of electricity pricesResearch on sustainable development highlights a connection between GGS and the inclination to invest in eco-friendly innovation (Song & Yu, 2018). However, the moderating role of energy pricing in the relationship between GGS implementation and green product development remains underexplored. A critical distinction exists between hybrid and electric vehicles: while electric cars are powered exclusively by electric motors, hybrid vehicles utilize a combination of internal combustion engines and electric assistance (Sanguesa et al., 2021). Studies suggest that producing an electric vehicle requires over twice the energy needed for a conventional car, despite its benefits in reducing greenhouse gas and NO2 emissions (see Han et al., 2024; Held & Baumann, 2011). Furthermore, the manufacturing of electric car batteries contributes to increased carbon emissions (Li, Xia & Guo, 2022), which may incentivize environmentally conscious companies to prioritize hybrid vehicles as a more balanced alternative.

Theoretically, social identity theory posits that individuals, including board members, managers, investors, and customers, are motivated to adopt behaviors and attitudes that enhance their group's positive image (Hornsey, 2008). Accordingly, automakers may continue investing in hybrid vehicles through GGS, even amid rising electricity prices, to address the challenges posed by electric vehicles, such as costs, capacity, and charging infrastructure. Moreover, electricity prices can act as a contextual factor influencing group norms, as suggested by social identity theory. When electricity prices rise, the relative benefits of hybrid vehicles become more apparent, reinforcing the commitment of both companies and consumers to sustainable practices. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2

Electricity prices positively moderate the relationship between green governance strategy and hybrid vehicle development.

Hybrid mobility and the triumph of positive sustainability performanceThe success of an environmental strategy should be evaluated based on both its corporate benefits and its ability to measure and control its actual environmental impact (Banerjee, 2002). Effective sustainability management can lead to tangible improvements in the corporate environmental and social outcomes. However, poorly managed sustainability initiatives can yield minimal benefits or even detract from corporate sustainability performance (Kaul & Luo, 2018). Consequently, examining the relationship between hybrid vehicle development and its impact on sustainability performance is crucial for understanding the practices of automakers.

Since investments in hybrid vehicles remain at an early stage, additional evidence is needed to substantiate the relationship between hybrid vehicle development, sustainability performance, and associated returns. Prior studies support the positive impact of hybrid vehicle investments on sustainability performance (García-Madariaga & Rodríguez-Rivera, 2017; Devinney, 2009). Siegel and Vitaliano (2007) argued that hybrid vehicle development is a CSR initiative, suggesting that companies engaging in green innovation achieve better sustainability outcomes than those without GGS. Green product innovation has been shown to enhance corporate sustainability performance through long-term sustainable growth expectations (Fernando et al., 2019). Green innovation has a significant and positive relationship with sustainable development. Empirical evidence also indicates that green innovation positively impacts sustainable development, improving economic, environmental, and social performance (see Ferreira et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2022).

Theoretically, social identity theory posits that when companies invest in green products, they aim to redefine their brand identity, signaling a commitment to environmental sustainability (Lyulyov et al., 2024; Olsen et al., 2014). Whitmarsh and O'Neill (2010) highlighted that hybrid vehicle development represents a pro-environmental identity, reflecting a corporation's environmental responsibility. Therefore, from the perspective of social identity theory, the decision to develop hybrid vehicles is not merely an operational choice; it represents a strategic, identity-driven approach aligning corporations with sustainability objectives while reinforcing their social credibility. Accordingly, we propose the following third hypothesis:

H3a

Hybrid vehicle development triggers corporations to adopt SDG 11 Sustainable cities and communities.

H3b

Hybrid vehicle development triggers corporations to adopt SDG 13 Climate action.

H3c

Hybrid vehicle development positively affects corporate environmental performance.

H3d

Hybrid vehicle development increases the achievement of corporate responsibility award(s).

Research methodologySampleThis study examines the relationships between green governance strategy (GGS), hybrid vehicle development, and sustainability performance, focusing on two primary contributing factors. First, as emphasized by Elon Musk, internal motivation ensures that automakers are genuinely committed to sustainable development. Second, external pressures encourage companies to adopt sustainable practices. Our analysis focuses on automobile manufacturers prioritizing sustainable vehicle development. Data were sourced from three primary databases: (1) the Refinitiv Eikon database to collect financial and non-financial data; (2) the U.S. Energy Information Administration database to collect electricity prices; and (3) the World Bank database to collect GDP data.

The initial sample comprised 1077 companies listed on global indices, identified through the Refinitiv database, specifically in the automobile industry based on the Global Industry Classification Standard.1 The sample period in this research was determined by the availability of data on hybrid vehicle development and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) metrics in the Refinitiv database for selected listed companies. Our analysis focused on green product innovation and environmentally friendly practices, including the adoption of SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and SDG 13 (Climate Action), as well as sustainability performance. Due to missing data on green practices, two prominent automakers, General Motors Co. and Volvo AB, were excluded, resulting in a final sample size of 42 companies from 15 countries. This yielded 294 observations across our three models for the 2015–2021 period, as detailed in Table 1. This sample size adequately captures within-entity and between-entity variations in the context of random-effects models for balanced panels (Wooldridge, 2010). Specifically, the total number of cross-sectional units is N = 42, derived from 294 observations over 7 periods. This aligns with the recommendation of 30 to 50 groups for robust variance component estimation (Clavrk & Linzer, 2015). Furthermore, the data set also meets the minimum requirements for predictor observations, with six predictors for Models 1 and 3 and seven predictors for Model 2, exceeding the threshold of 60 to 90 observations recommended by Scherbaum and Ferreter (2009).

Research sample.

| A. Sample selection | ||

|---|---|---|

| Indices | No. of automobile manufacturers | |

| Borsa Istanbul | 2 | |

| Deutsche Boerse AG | 1 | |

| Electronic Share Market | 2 | |

| Euronext - Euronext Paris | 3 | |

| Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Ltd | 4 | |

| Korea Stock Exchange | 2 | |

| London Stock Exchange | 2 | |

| Nasdaq Stockholm AB | 1 | |

| National Stock Exchange of India | 4 | |

| New York Stock Exchange | 4 | |

| Shanghai Stock Exchange | 5 | |

| Six Swiss Exchange | 1 | |

| Tokyo Stock Exchange | 9 | |

| Toronto Stock Exchange | 1 | |

| Xetra | 3 | |

| Total initial sample | 44 | |

| Less | ||

| Companies with missing ESG data | 2 | |

| Total final sample | 42 | |

| B. Country composition | ||

| No. | Country | No. ofautomobile manufacturers |

| 1 | Canada | 1 |

| 2 | China | 7 |

| 3 | France | 3 |

| 4 | Germany | 4 |

| 5 | Hong Kong | 1 |

| 6 | India | 4 |

| 7 | Ireland; Republic of | 2 |

| 8 | Italy | 1 |

| 9 | Japan | 9 |

| 10 | Korea; Republic (S. Korea) | 2 |

| 11 | Netherlands | 1 |

| 12 | Switzerland | 1 |

| 13 | Turkey | 2 |

| 14 | United Kingdom | 1 |

| 15 | United States of America | 3 |

| Total | 42 | |

Random-effects generalized least squares (GLS) models were employed to analyze the panel data, as the Hausman test indicated that random-effects models were more appropriate for capturing between-firm variations. This approach leverages the longitudinal structure of the data while assuming that firm-specific effects are uncorrelated with predictors, enabling efficient estimation and accounting for potential omitted variables (Laird & Ware, 1982). To ensure model robustness, several diagnostic tests were performed. In the beginning, we assessed multicollinearity by calculating the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for each explanatory variable, all well below the threshold of 10, indicating no significant multicollinearity. We then checked for endogeneity using the Durbin-Wu-Hausman (DWH) test, which confirmed that our model specifications were appropriate. Additionally, we tested for heteroskedasticity using the Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg test, which showed no significant heteroskedasticity, and for autocorrelation using the Wooldridge test, which revealed no significant serial correlation. These diagnostic procedures validated the reliability and robustness of the random-effects GLS models.

MeasuresGreen governance strategy (GGS) is defined as corporate actions aimed at reducing environmental impact, aligning with environmental values, and reinforcing a responsible identity for both organizations and consumers. To identify the strategy, we drew from existing literature and utilized to the Refinitiv Eikon database, focusing on a comprehensive range of proactive environmental initiatives outlined in Table 2. Each variable reflects practices and disclosures that are widely recognized as critical to enhancing corporate environmental accountability. This approach aligns with broader trends in corporate sustainability and green governance.

- •

Green Capex Target (GREENCT) indicates whether a company has set specific targets for allocating capital expenditure to climate-related opportunities. Strategic capital allocation toward environmental sustainability is linked to long-term profitability and environmental performance (Bhandari & Javakhadze, 2017).

- •

Green Revenues Target (GREENRT) reflects whether a company targets increasing revenue from green products or services, such as hybrid vehicles. Studies have shown that green revenue targets are a significant driver for companies’ adoption of sustainable practices, as they directly impact corporate profitability while also meeting growing consumer demand for sustainable products (Huang et al., 2024).

- •

Environmental Partnerships (ENVIP) measures a company's involvement in collaborations with NGOs, government bodies, or industry groups to address environmental issues, recognized as a strategic approach to enhancing sustainability initiatives (Rondinelli & London, 2003).

- •

Climate-Related Risks Assessment Process (CRRAP) assesses whether a company has processes for identifying and managing climate-related risks. Alignment with frameworks such as the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) highlights the importance of proactive risk management (O'Dwyer & Unerman, 2020).

- •

Environmental Management Team (ENVIMT) captures the presence of a dedicated environmental management team, distinct from the board of directors, to implement sustainability initiatives effectively (Papagiannakis & Lioukas, 2018).

Study variables.

| Variable(s) | Definitions/Measurement | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Hybrid Vehicles (HYBVE) | A dummy variable that equals one if the company is developing green vehicles, hybrid vehicles or technologies, electric vehicles, zero for otherwise. | Refinitiv |

| Green Governance Strategy (GGS)(Score: Max: 5/Min: 0) | A set of initiatives to control the effect of corporate operation on environmental degradation, which that is related to whether the companies did any of following:Green Capex Target (GREENCT): A dummy variable that equals one if the company has disclosed a target for the share or amount of expenditure deployed to climate-related opportunities, zero for otherwise.Green Revenues Target (GREENRT): A dummy variable that equals one if the company has disclosed a target to increase the share of green revenues in its overall sales, zero for otherwise.Environmental Partnerships (ENVIP): A dummy variable that equals one if the company report on partnerships or initiatives with specialized NGOs, industry organizations, governmental or supra-governmental organizations, which are focused on improving environmental issues, zero for otherwise.Climate Related Risks Assessment Process (CRRAP): A dummy variable that equals one if the company describes its process for identifying and assessing climate-related risks, zero for otherwise.Environmental Management Team (ENVIMT): A dummy variable that equals one if the company has an environmental management team, including employees of the company, who perform the functions dedicated to environmental issues on a day-to-day basis and are not the board committees (directors), zero for otherwise. | Refinitiv |

| CSR Performance | ||

| SDG 11 Sustainable Cities and Communities (SDG11) | A dummy variable that equals one if the company supports the UN Sustainable Development Goal 11 to make cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable, zero for otherwise. | Refinitiv |

| SDG 13 Climate Action (SDG13) | A dummy variable that equals one if the company support the UN Sustainable Development Goal 13 to take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts, zero for otherwise. | Refinitiv |

| Environmental Performance (ENVIP) | The log of the overall company score measuring the company's impact on living and non-living natural systems, including the air, land, and water, as well as complete ecosystems. | Refinitiv |

| CSR Awards (CSRA) | A dummy variable that equals one if the company has received an award for its social, ethical, community, or environmental activities or performance, zero for otherwise. | Refinitiv |

| Emission Score (EMISS) | The log of the overall company score measuring the company's commitment and effectiveness toward reducing environmental emission in the production and operational processes. | Refinitiv |

| Environmental Controversies (ENVIC) | A dummy variable that equals one if the company is under the spotlight of the media because of a controversy linked to the environmental impact of its operations, zero for otherwise. | Refinitiv |

| Moderating Variable | ||

| Electricity Prices (ELEC) | The log of the annualized monthly-average retail electricity prices adjusted by the consumer price index (CPI) | U.S. Energy Information Administration |

| Control Variables | ||

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) | The log of GDP in the country where the companies based | The World Bank |

| CEO Chairman Duality (CCDUAL)) | A dummy variable that equals one if the CEO simultaneously chair the board, zero for otherwise. | Refinitiv |

| Independent Board Members (INDBM) | The percentage of independent board members as reported by the company. | Refinitiv |

| Firm Size (FSIZE) | The log of total assets. | Refinitiv |

| Leverage (LEV) | Measured as long-term debt divided by total capital at the end of the fiscal period and is expressed as percentage. | Refinitiv |

| Profitability (PROFIT) | Measured as net income divided total assets | Refinitiv |

Hybrid Vehicles (HYBVE) represent a tangible commitment to environmental sustainability, significantly influencing public perception and enhancing social recognition (Whitmarsh & O'Neill, 2010). The first research objective is to identify the key factors of green governance strategy (GGS) that drive automobile manufacturers to invest in hybrid vehicles, as developed in Model 1.

Model 1:

Moderating Effect of Electricity Prices (ELEC) is expressed as GGSxELEC, representing an interaction term for green governance strategy and electricity prices. According to H2, β2 is expected to be positive, as higher electricity prices may prompt companies to reconsider investments in green strategies. Model 2 also incorporates GDP as a control variable to account for economic conditions. The second research objective evaluates the impact of green investments in hybrid vehicle development under the moderating effect of electricity prices, as detailed in Model 2.

Model 2:

Corporate Sustainability Performance (CSP) is assessed using proxies, including SDGs 11 and 13, environmental performance (ENVIP), and CSR awards (CSRA). These indicators align with sustainability and corporate responsibility goals. SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and SDG 13 (Climate Action) reflect global commitments to sustainable urbanization and climate action (United Nations, 2021). ENVIP measures the company's direct impact on natural systems, linking corporate practices to environmental stewardship (Brulhart et al., 2019). CSRA validates a company's achievements in CSR through awards (Li et al., 2018). Together, these proxies offer a comprehensive framework for evaluating CSP. The third research objective investigates the effect of hybrid vehicle development on sustainability performance, as formulated in Model 3.

Model 3:

To ensure validity and significance, firm-level characteristics were controlled. Specifically, we controlled for CEO-chairman duality (CCDUAL), independent board members (INDBM), firm size (FSIZE), and firm leverage (LEV). Independent directors and firm size impact CSR practices positively, while CEO duality has a negative impact (Singh & Rahman, 2021). Additionally, we included leverage as a control variable, since low-leverage companies can better manage agency problems related to overinvestment in CSR/sustainability (Ye & Zhang, 2011).

ResultsDescriptive statisticsTable 3 reports the descriptive statistics for the study's variables. The findings show that 95 % of the sampled companies had developed hybrid vehicles. The GGS score ranges from 0 to 3, with a mean value of 1.40. Adoption rates for SDG 11 and SDG 13 are 40 % and 45 %, respectively. These low averages suggest that many automobile companies, a sector among the most polluting industries, have overlooked critical sustainable development goals. Consequently, it is imperative to encourage automobile manufacturers to adopt environmentally sustainable practices and goals.

Descriptive statistics.

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HYBVE | 294 | 0.95 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| GGS | 294 | 1.40 | 0.79 | 0.00 | 3.00 |

| SDG11 | 294 | 0.40 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| SDG13 | 294 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| ENVIP | 294 | 4.15 | 0.49 | 1.72 | 4.59 |

| CSRA | 294 | 0.72 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| CCDUAL | 294 | 0.39 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| INDBM | 294 | 0.49 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| FSIZE | 294 | 24.28 | 1.47 | 21.27 | 27.11 |

| LEV | 294 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 1.97 |

| ROA | 294 | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.16 | 0.27 |

| ELEC | 294 | 2.36 | 0.02 | 2.33 | 2.41 |

| GDP | 294 | 2.92 | 4.18 | −11.03 | 24.37 |

Note:Table 2 fully defines all the variables used.

Despite the growing importance of ESG scores for enhancing corporate reputation, our data set from 2015 to 2021 reveals a minimum ESG score of 9.5 points (encompassing three ESG pillars) and an average of 64.01. Alarmingly, 60 % and 55 % of companies disregarded SDG 11 and SDG 13, respectively. However, companies receiving CSR awards achieved an average ESG score of 72 %, suggesting that hybrid vehicle development aligned with specific SDGs may be a significant driver of such recognition.

Regarding the control variables, the mean value of CEO duality is 0.39, indicating that most companies separate the roles of CEO and chairman. The mean value of independent directors is 0.49, reflecting moderate board independence. With a mean of 24.28 (minimum of 21.27 and maximum of 27.11), variations in firm size could influence the hypotheses. The mean of leverage is 25 %, indicating limited reliance on external financing. The mean of profitability is 5 %, with a minimum of −0.16 and a maximum of 27 %, revealing that companies urgently need to implement effective strategies to enhance corporate performance. The mean values for electricity prices and GDP are 2.36 and 2.92, respectively. Notably, GDP exhibits significant variation, ranging from −11.03 to 24.37.

Table 4 presents the correlation coefficients for the dependent, independent, and control variables. The analysis reveals strong correlations among some independent variables, indicating the potential risk of multicollinearity in the regression models. Appropriate diagnostic tests, including Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), were performed to address this concern.

Pearson's correlation matrix.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. HYBVE | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 2. GGS | 0.32*** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 0.00 | |||||||||||||

| 3. SDG11 | 0.15** | 0.36*** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 0.01 | 0.00 | ||||||||||||

| 4. SDG13 | 0.17*** | 0.37*** | 0.84*** | 1 | |||||||||

| 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||||||||||

| 5. ENVIP | 0.61*** | 0.72*** | 0.34*** | 0.36*** | 1 | ||||||||

| 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| 6. CSRA | 0.26*** | 0.48*** | 0.25*** | 0.23*** | 0.46*** | 1 | |||||||

| 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||||||||

| 7. CCDUAL | −0.05 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.17*** | 1 | ||||||

| 0.38 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.77 | 0.70 | 0.00 | ||||||||

| 8. INDBM | 0.15** | 0.11* | 0.28*** | 0.24*** | 0.13* | −0.02 | 0.20*** | 1 | |||||

| 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.77 | 0.00 | |||||||

| 9. FSIZE | −0.14** | 0.38*** | 0.12* | 0.11* | 0.27*** | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.17*** | 1 | ||||

| 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.46 | 0.00 | ||||||

| 10. LEV | 0.12* | 0.12* | 0.11 | 0.15** | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.20*** | 0.26*** | 0.12* | 1 | |||

| 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | |||||

| 11. ROA | 0.09 | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.04 | −0.19*** | −0.11 | −0.34*** | −0.24*** | 1 | ||

| 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.60 | 0.86 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| 12. ELEC | 0.06 | 0.16** | 0.33*** | 0.38* | 0.15** | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.14* | 0.05 | −0.02 | −0.07 | 1 | |

| 0.32 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.43 | 0.74 | 0.02 | 0.40 | 0.70 | 0.23 | |||

| 13. GDP | −0.06 | −0.22*** | −0.11 | −0.17* | −0.26*** | 0.03 | −0.09 | 0.04 | −0.25*** | −0.14** | 0.24*** | 0.14** | 1 |

| 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.66 | 0.11 | 0.46 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

Note: *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively. Table 2 fully defines all the variables used.

Our multiple regression analysis results are reported in Tables 5 and 6. As shown in Table 5, Models 1 and 2 of the first state were statistically significant at p < 0.01. Notably, in Model 1, GGS positively impacted hybrid vehicles (HYBVE) (β = 0.0644) at the 1 % significance level, supporting H1 and aligning with previous findings by Guo et al. (2020). This result is consistent with social identity theory, as investing in hybrid vehicles allows corporations to demonstrate their commitment to environmental protection and a zero-carbon economy (Whitmarsh & O'Neill, 2010).

Random effects GLS regression results.

| Indep. and control variables | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|

| HYBVE | HYBVE | |

| GGS | 0.0644*** | |

| (0.0180) | ||

| GGS*ELEC | 0.0274*** | |

| (0.00772) | ||

| CCDUAL | −0.0106 | −0.0108 |

| (0.0264) | (0.0265) | |

| INDBM | 0.0535 | 0.0530 |

| (0.0618) | (0.0620) | |

| FSIZE | −0.0344 | −0.0341 |

| (0.0177) | (0.0179) | |

| LEV | 0.0298 | 0.0294 |

| (0.0544) | (0.0545) | |

| PROFIT | −0.144 | −0.154 |

| (0.178) | (0.181) | |

| GDP | 0.000706 | |

| (0.00329) | ||

| _cons | 1.535*** | 1.629*** |

| (0.422) | (0.430) | |

| N | 294 | 294 |

| Year Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes |

| Wald Chi(2) | 28.34** | 28.15* |

Note: *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively. Values in parentheses are clustering standard errors at the firm level. Table 2 fully defines all the variables used.

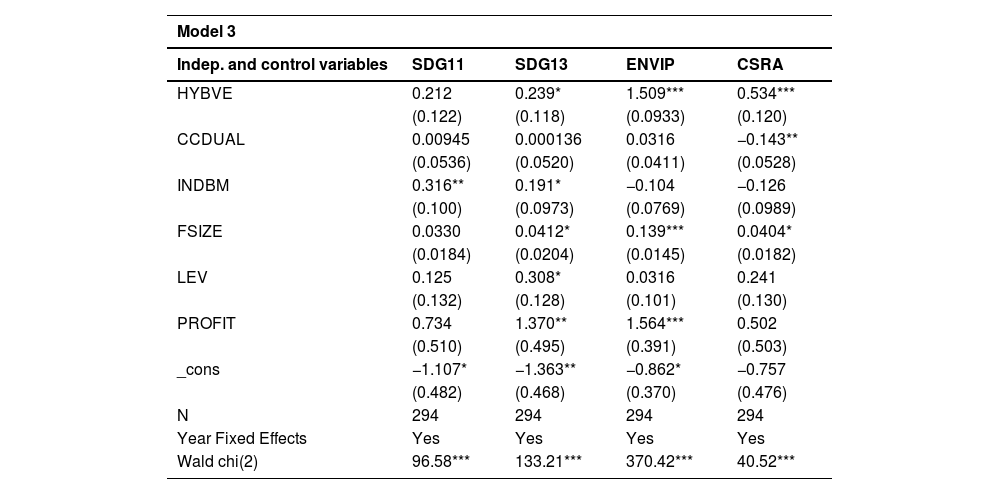

Regression results on hybrid vehicles and sustainability performance.

| Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indep. and control variables | SDG11 | SDG13 | ENVIP | CSRA |

| HYBVE | 0.212 | 0.239* | 1.509*** | 0.534*** |

| (0.122) | (0.118) | (0.0933) | (0.120) | |

| CCDUAL | 0.00945 | 0.000136 | 0.0316 | −0.143** |

| (0.0536) | (0.0520) | (0.0411) | (0.0528) | |

| INDBM | 0.316** | 0.191* | −0.104 | −0.126 |

| (0.100) | (0.0973) | (0.0769) | (0.0989) | |

| FSIZE | 0.0330 | 0.0412* | 0.139*** | 0.0404* |

| (0.0184) | (0.0204) | (0.0145) | (0.0182) | |

| LEV | 0.125 | 0.308* | 0.0316 | 0.241 |

| (0.132) | (0.128) | (0.101) | (0.130) | |

| PROFIT | 0.734 | 1.370** | 1.564*** | 0.502 |

| (0.510) | (0.495) | (0.391) | (0.503) | |

| _cons | −1.107* | −1.363** | −0.862* | −0.757 |

| (0.482) | (0.468) | (0.370) | (0.476) | |

| N | 294 | 294 | 294 | 294 |

| Year Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Wald chi(2) | 96.58*** | 133.21*** | 370.42*** | 40.52*** |

Note: *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively. Values in parentheses are clustering standard errors at the firm level. Table 2 fully defines all the variables used.

In Table 5, Model 2 illustrates the moderating effect of ELEC (electricity prices) on the relationship between GGS and the development of hybrid vehicles. GGS*ELEC shows a positive and statistically significant coefficient (β = 0.0274) at the 1 % significance level, supporting H2. To our knowledge, this is the first exploration of sustainability practices in the automobile industry. Our findings align with Li et al. (2022) and are consistent with the principles of social identity theory (Hornsey, 2008; Turner, 1975). Since electric car battery production generates substantial carbon emissions, corporations with green initiatives prefer investing in hybrid vehicles, even amid rising electricity prices, to mitigate the challenges posed by electric vehicles.

Table 6 presents the results of Model 3, which tested H3a, H3b, H3c, and H3d. These findings underscore the positive effects of hybrid vehicles on eco-friendly and sustainable SDGs, environmental performance, and the achievement of CSR award achievements. The results indicate a positive coefficient (β = 0.212) for SDG 11, while SDG 13 (β = 0.239) is significant at the 10 % level. ENVIP (β = 1.509) and CSRA (β = 0.534) are significant at the 1 % level. These findings support H3a, H3b, H3c, and H3d, respectively. However, the result for H3a is not significant. Table 6 also shows that CCDUAL, INDBM, and FSIZE positively and significantly impact corporate sustainability performance. Interestingly, CCDUAL is negatively correlated with SDG 13 and CSR award achievements, while INDBM is positively associated with SDGs adoption among automakers, particularly SDG 11 and SDG 13. These findings are supported by Taglialatela et al. (2023). Furthermore, FSIZE positively correlates with environmental variables, including SDG 13 and environmental performance scores.

Robustness checksVariables substitutionTo ensure the robustness of our results, we conducted several sensitivity analyses, as shown in Table 7. For Model 1, we re-estimated the model equation by substituting GGS with the board's environmental orientation (Moussa et al., 2020). This included variables such as board independence, board gender diversity, financial expertise on the audit committee, sustainability-based compensation policy, and multiple directorships. Additionally, we examined the moderating effect of electricity prices on the connection between board orientation and hybrid vehicle development. Although board environmental orientations positively correlated with hybrid vehicle development, the results were insignificant. This outcome highlights that our GGS are more closely tied to corporate strategies than board characteristics (see Moussa et al., 2020). In Model 3, we replaced ENVIP and CSRA with EMISS (emission score) and ENVIC (corporate environmental controversies), respectively. The results remained consistent, as shown in Model 3 of Table 7.

Regression results with variables substitution.

| Indep. and control variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HYBVE | HYBVE | SDG11 | SDG13 | EMISS | ENVIC | |

| BENVIO | 0.00293 | |||||

| (0.0146) | ||||||

| BENVIO*ELEC | 0.00178 | |||||

| (0.00604) | ||||||

| HYBVE | 0.0755 | 0.169 | 1.356*** | 0.292* | ||

| (0.172) | (0.174) | (0.172) | (0.134) | |||

| CCDUAL | −0.0133 | −0.0134 | −0.0244 | −0.0464 | −0.123 | −0.0308 |

| (0.0269) | (0.0270) | (0.0769) | (0.0782) | (0.0784) | (0.0602) | |

| INDBM | 0.111 | 0.106 | 0.642*** | 0.582*** | 0.520** | 0.0210 |

| (0.0673) | (0.0676) | (0.157) | (0.155) | (0.170) | (0.119) | |

| FSIZE | −0.00755 | −0.00878 | 0.0351 | 0.0520 | 0.201*** | 0.134*** |

| (0.0184) | (0.0185) | (0.0351) | (0.0326) | (0.0480) | (0.0248) | |

| LEV | 0.00735 | 0.00747 | −0.0361 | −0.00724 | −0.0170 | 0.0881 |

| (0.0549) | (0.0550) | (0.167) | (0.174) | (0.161) | (0.134) | |

| PROFIT | −0.187 | −0.163 | −0.750 | −0.0386 | 0.176 | 0.155 |

| (0.176) | (0.180) | (0.558) | (0.594) | (0.523) | (0.461) | |

| GDP | −0.00139 | |||||

| (0.00211) | ||||||

| _cons | 1.084* | 1.115* | −0.781 | −1.241 | −2.284 | −3.327*** |

| (0.450) | (0.450) | (0.884) | (0.829) | (1.185) | (0.631) | |

| N | 294 | 294 | 294 | 294 | 294 | 294 |

| rmse in estimates of β | 0.111 | 0.112 | 0.376 | 0.414 | 0.334 | 0.323 |

Note: *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively. Values in parentheses are clustering standard errors at the firm level. Table 2 fully defines all the variables used.

A Difference-in-Differences (DiD) estimate measures the difference in outcomes before and after treatment between a treatment group and a control group (Abadie, 2005; Goodman-Bacon, 2021). Our research design utilizes the DiD methodology to examine whether GGS enhances hybrid vehicle production (RQ1) and whether hybrid vehicle production improves corporate sustainability performance (RQ2) (Abadie, 2005). Specifically, for RQ1, DiD evaluates companies with and without GGS over time, isolating the impact of the strategy while controlling for external influences. For RQ2, DiD assesses changes in sustainability performance before and after hybrid vehicle production, comparing producers and non-producers. This approach allows for robust causal inference, making DiD a valuable framework for evaluating the effects of GGS and hybrid vehicle production on sustainability outcomes.

To further ensure robustness, we applied the DiD estimator to Model 1 and Model 3, using 2015–2018 as the pre-period and 2019–2021 as the post-period. The year 2018 was selected as the transition point to address potential endogeneity concerns, as significant external events influenced corporate sustainability strategies. For instance, in October 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued a report warning of only 12 years to limit global warming to 1.5 °C (Rhodes, 2019). Additionally, the Paris Agreement "rulebook" was enforced at COP24 in 2018, prompting corporations to revise their green strategies (Schneider et al., 2019).

Table 8 indicates that the R-squared values range from 0.101 to 0.549, explaining 10.1 % to 54.9 % of the variance. Notably, the coefficient for GGS is 0.0845 at the 1 % level, indicating a significant positive effect. HYBVE exhibits negative coefficients (−0.305 and −0.355) at the 1 % level. The post-2018 period (Year ≥ 2018) has a positive coefficient (0.295) at the 1 % significance level, indicating significant changes. The interaction term HYBVE*Year ≥ 2018 is 0.184 at the 5 % significance level, indicating a notable shift in hybrid vehicle impacts post-2018. Therefore, these results validate our main findings.

DiD regression results.

| Model 1 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HYBVE | SDG11 | SDG13 | ENVIP | CSRA | |

| GGS | 0.0845*** | ||||

| (0.0206) | |||||

| HYBVE | −0.305*** | −0.355*** | 1.473*** | 0.295 | |

| (0.0562) | (0.0609) | (0.385) | (0.264) | ||

| Year ≥ 2018 | 0.00773 | 0.295*** | 0.359*** | 0.134*** | −0.0164 |

| (0.0490) | (0.064) | (0.0675) | (0.0377) | (0.0454) | |

| GGS*Year ≥ 2018 | 0.000843 | ||||

| (0.0305) | |||||

| HYBVE *Year ≥ 2018 | 0.184** | 0.199*** | 0.0171 | 0.0534 | |

| (0.0575) | (0.0528) | (0.0276) | (0.0617) | ||

| _cons | 0.829*** | 0.469*** | 0.523*** | 2.668*** | 0.438 |

| (0.0320) | (0.0372) | −0.0384 | −0.364 | −0.254 | |

| N | 294 | 294 | 294 | 294 | 294 |

| R-sq | 0.101 | 0.309 | 0.355 | 0.549 | 0.019 |

| adj. R-sq | 0.092 | 0.301 | 0.348 | 0.544 | 0.009 |

| rmse | 0.203 | 0.302 | 0.319 | 0.161 | 0.282 |

Note: *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively. Values in parentheses are clustering standard errors at the firm level. Table 2 fully defines all the variables used.

The main purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between green governance strategy (GGS), the development of hybrid vehicles (HYBVE), and sustainability performance (SDG 11, SDG 13, ENVIP, CSRA). We treated HYBVE as a dependent variable in Models 1 and 2, and as an independent variable in Model 3. Our findings significantly contribute to the literature on green business strategy and sustainability performance, particularly in corporate identity management.

Our study distinguishes itself from previous research in how we measure GGS, especially in the context of the automobile industry where capital investments are typically substantial. This approach enables us to shape a more efficient GGS that meets the need for proactive environmental management strategies. Consequently, H1 is supported, demonstrating that GGS is positively and significantly associated with the development of hybrid vehicles. This finding aligns with Guo et al. (2020), which emphasizes the critical role of GGS in enabling companies to transition toward a zero-carbon economy. However, our study goes beyond existing perspectives by reframing GGS not merely as a reactive measure to regulatory pressures or market demands but as a proactive strategy for reshaping corporate identity. Drawing on social identity theory, we posit that GGS serves as a mechanism for companies to publicly align their corporate identity with environmental values and the zero-carbon movement. This extends current theoretical understandings by demonstrating that implementing GGS is not only about compliance but also about leveraging sustainability as a core component of corporate identity, which can influence how companies are perceived in the market and among stakeholders. In this regard, our research critiques previous studies (e.g., Guo et al., 2020; Sahoo et al., 2023) that primarily view GGS as a tool for compliance or risk mitigation, instead positioning it as a strategic identity-building tool that redefines corporate engagement with environmental sustainability.

Regarding H2, our findings contribute to the economic sustainability literature by confirming the moderating effect of electricity prices on the relationship between companies with GGS and the development of hybrid vehicles. While prior studies, including those by Li et al. (2022), have explored similar themes, our results provide a more profound theoretical contribution by directly linking this interactive relationship to social identity theory. Specifically, the significant carbon emissions associated with electric car battery production suggest that companies aiming to project an environmentally responsible identity may prioritize hybrid vehicles over fully electric ones, particularly when electricity prices rise. This finding challenges the assumption that higher electricity prices universally push companies toward fully electric alternatives. Instead, it highlights how economic pressures can drive firms to sustain hybrid vehicle production as a more balanced solution. Additionally, the insignificant relationship between GDP and hybrid vehicle development further complicates prior assumptions about the straightforward connection between economic growth and sustainability efforts.

Moving to H3, the relationship between hybrid vehicle development and SDG 11 (H3a) is positive but not significant. This result may be attributed to the low adoption rates of SDG 11 within the sample (39.80 %). It suggests that the relationship between hybrid vehicle production and SDGs adoption becomes significant only when automobile manufacturers actively commit to these SDGs, indicating that prior studies (e.g., Chen, 2001; Lyulyov et al., 2024) may have underestimated the critical role of such commitment in linking production practices to sustainability goals. In contrast, H3b and H3c are supported, confirming that hybrid vehicle development positively impacts SDG 13 (Climate Action) and corporate environmental performance, this aligns with Khan et al. (2022). Specifically, the study emphasizes that producing low-carbon vehicles is not just an environmental obligation but also a significant driver of corporate social recognition, challenging existing models that view sustainability solely through the lens of financial performance. Social identity theory furthers insight into these findings, suggesting that companies producing hybrid vehicles bolster their pro-environmental identity, thereby fulfilling both their social and environmental responsibilities (Olsen et al., 2014). This conceptualization, however, calls for a critical re-examination of how "green" identities are constructed and the broader implications for corporate behavior.

Furthermore, the positive association between hybrid vehicle production and CSR awards (H3d) complicates traditional CSR models, implying that environmental innovations contribute directly to external recognition rather than merely serving as by-products of broader corporate social efforts. The control variables provide further insights, with independent board members (INDBM) positively correlating with SDGs 11 and 13 (Taglialatela et al., 2023). However, CEO duality's negative impact on CSR award achievement raises concerns about the potential misalignment between centralized decision-making and effective sustainability outcomes. These findings prompt a re-evaluation of how governance, corporate identity, and environmental actions intersect, indicating that integrating sustainability into corporate strategies is more complex and context-dependent than previously understood.

Our study significantly advances the field by challenging conventional assumptions regarding the role of green innovation in the automobile industry. We propose a nuanced framework for understanding whether investments in green products genuinely align with sustainable corporate objectives. Contrary to earlier approaches that repeatedly treated green products as marginal or supplementary, our findings reveal that companies with strong GGS are the primary drivers of hybrid vehicle development. This emphasizes a strategic alignment between environmental responsibility and corporate identity. Hybrid vehicles are positioned not merely as marketable innovations but as a defining aspect of corporate identity that directly addresses environmental challenges while supporting long-term sustainable profitability (see Wang et al., 2022). Thus, this product line repositions hybrid vehicles as central to enhancing environmental performance, a priority that remains underappreciated in sustainability discussions within the automobile industry (Kim, 2023). By emphasizing the crucial role of hybrid vehicle production in driving corporate sustainability, our study offers valuable insights into how automakers can effectively leverage GGS to achieve both environmental and economic objectives in an industry increasingly shaped by regulatory and societal expectations (e.g., Madzík et al., 2024; Shan et al., 2023).

Theoretical implicationsThese findings advance social identity theory by illustrating how corporations construct and maintain pro-environmental identities in response to societal pressures and sustainability goals. Unlike traditional applications of social identity theory, which often center on individuals' group affiliations (Postmes et al., 2005; Turner, 1975), this study extends the theory to corporate behavior, illustrating how companies leverage GGS and hybrid vehicle development to build an identity aligned with societal values regarding environmental responsibility.

First, the study reveals that corporations engage in sustainability practices not solely for competitive or economic gain but to establish a distinct, socially valued identity as environmentally responsible entities. This shifts the focus from purely financial motivations to identity-driven motivations, where companies aim to be seen as leaders in environmental stewardship (e.g., Madzík et al., 2024; Shan et al., 2023). This nuance advances social identity theory by positioning corporate identity as a proactive alignment with social and environmental expectations, particularly relevant in the automobile industry, where GGS can significantly reduce environmental impact (see Shan et al., 2023).

Second, by identifying electricity prices as a moderating factor in GGS and hybrid vehicle production, the study introduces an economic dimension to corporate social identity. The necessity to sustain a green identity despite fluctuating energy costs adds complexity to identity maintenance, suggesting that companies with strong GGS may absorb such pressures as part of their commitment to environmental identity (Lyulyov et al., 2024). This insight expands social identity theory by illustrating how external economic factors impact the corporate identity narrative, pushing companies to reinforce their identity as sustainable entities amid economic challenges.

Finally, governance structures emerge as key components of corporate social identity. Independent board members enhance alignment with SDGs, reinforcing the company's environmental and social identity (Martínez‐Ferrero & García‐Meca, 2020). Conversely, CEO duality negatively affects CSR recognition, suggesting that diffused leadership may strengthen, while concentrated leadership may hinder, a cohesive social identity. These findings advance social identity theory by demonstrating that internal governance and external pressures together shape the construction and credibility of corporate social identities in sustainability contexts (Toufighi et al., 2024).

Practical implicationsOur findings offer targeted and strategic propositions that can directly inform automakers, policymakers, and stakeholders about sustainable transportation. First, this study highlights five actionable components of GGS: setting measurable green capital and revenue targets, building strategic environmental partnerships, conducting regular climate risk assessments, and forming dedicated environmental management teams. The strategy is essential for automakers seeking to comply with government emissions and sustainability targets. For policymakers, recommendations include making GGS mandatory for automakers to access government incentives. For instance, companies that set measurable green targets and conduct climate risk assessments could qualify for tax credits or research grants to develop clean technologies (see Helfaya et al., 2023a; Madzík et al., 2024).

Second, rapid economic growth can strain energy resources, leading to potential electricity supply issues that drive up vehicle production costs (L. Zhang et al., 2023). Despite these rising electricity prices, our findings highlight that hybrid vehicle production remains vital for establishing a responsible corporate image (see Kim, 2023; Wang et al., 2022). Policymakers can support this alignment by developing guidelines that mitigate green production costs through incentives like subsidies for renewable energy in manufacturing or grants for energy-efficient technology investments (Shan et al., 2023). Such measures would enable automakers to address financial challenges while maintaining their commitment to low-carbon vehicle production.

Third, government policy can directly drive the production of hybrid vehicles by integrating environmental levies on high-emission vehicles and offering financial incentives for low-emission alternatives (e.g., R. J. Zhang et al., 2024). Policymakers could expand the scope of initiatives, such as the car scrappage scheme, to provide additional benefits for low-emission and hybrid vehicles, offering automakers a clear path for transitioning to green vehicle lines (see, Marin & Zoboli, 2020; R. J. Zhang et al., 2024). Furthermore, implementing eco-labelling standards and setting minimum percentages of green vehicles in corporate fleets can encourage automakers to prioritize sustainable product lines, aligning with the broader goals of sustainable transportation (e.g., Lyulyov et al., 2024).

Finally, policymakers should encourage public-private partnerships, particularly in areas of technology advancement and energy-efficient manufacturing (see Madzík et al., 2024; Shan et al., 2023). These partnerships can provide automakers with strategic support to achieve both financial and non-financial goals, thereby enabling emissions reduction on a larger scale.

Research limitations and avenues for future researchWhile the study offers valuable insights and implications, it has some limitations that pave the way for future research. First, the sample size is relatively small, consisting of only 42 companies from the automobile sector, with data covering a narrow timeframe from 2015 to 2021, given data availability. Although the study focuses on the automobile industry to investigate its GGS and their impacts on sustainability performance, incorporating companies from other sectors developing hybrid vehicles could broaden the research focus. Future studies could expand the scope by including companies from multiple sectors, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of hybrid vehicle development and its use across industries. Second, the automobile sector has been undergoing innovation progress, playing a crucial role in the economy due to its close connections to other industries, such as transportation, logistics, travel, and tourism. Although we considered the moderating effect of electricity prices and GDP factors in our model, future research could examine other economic factors as moderating or control variables (e.g., oil prices, Consumer Price Index (CPI), and national income) to provide better results. Third, we employed a quantitative research approach, leaving the possibility open for further studies to utilize a mixed research methodology. A comprehensive corporate strategy should consider both corporate and customer viewpoints when addressing hybrid vehicles; therefore, future studies could integrate corporate perspectives (e.g., corporate competitive advantages) and customer perspectives (e.g., consumer's awareness and purchasing power) to enrich the existing literature on GGS, hybrid vehicle development and sustainable development.

Data availability statementThe data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAkrum Helfaya: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Phuong Bui: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.