The entrepreneurship literature has long recognized the importance of education in fostering successful self-employment, yet a significant gap exists in our understanding of how the political economy of vocational education systems influences the financial success of self-employed graduates. We focus on vocational education systems that are collectivist—namely, collective decision making and stakeholder collaboration to align training with labor market needs and to promote social cohesion—and statist—a centrally controlled vocational education system directed by the state, aiming to align training with national development goals and to prioritize economic needs. Our study analyzed 6924 participants who received vocational education from collectivist systems (Czech Republic and Denmark) and statist systems (Finland and Norway). The findings show a significant earnings gap between employed and self-employed receiving vocational education in statist systems, and a non-significant difference in earnings between employed and self-employed in collectivist systems. The findings have implications for how the type of vocational training affects the earnings gaps among the employed and self-employed.

Vocational educational training (VET) programs play a crucial role in developing technical skills and preparing individuals for specific trades and industries (Chuan & Ibsen, 2022). These programs offer practical, hands-on experience and industry-specific expertise that are increasingly valuable in today's dynamic labor market (Galvão et al., 2018). Recent studies have highlighted the significance of VET in enhancing entrepreneurial competencies, such as problem solving, decision making, and opportunity recognition, positioning it as a valuable tool for those seeking to start their own businesses (Bairagya, 2021).

The political economy of VET systems provides a theoretical framework for understanding how different approaches to vocational education might influence entrepreneurial outcomes. Historically, VET-intensive countries have organized their education and training systems in two primary ways: collectivist and statist (Chuan & Ibsen, 2022). Collectivist systems, exemplified by countries such as Germany, involve heavy employer participation in curriculum design and apprenticeship offerings, focusing on practical industry or firm-specific skills. In contrast, statist systems, as seen in Sweden, feature less employer involvement and a state-set curriculum emphasizing general skills. These institutional differences in VET systems intersect with human capital theory and theories of entrepreneurial self-efficacy, potentially influencing the development of entrepreneurial skills and subsequent outcomes.

While the importance of VET in fostering entrepreneurship is well established, there is a significant gap in our understanding of how different VET systems impact entrepreneurial outcomes, particularly earnings. This study addresses this gap by asking: Do differences in the political economy of VET systems influence entrepreneurship earnings gaps? This question is crucial as VET plays a vital role in preparing individuals for income-generating occupations, especially for those who may turn to self-employment out of necessity rather than choice (Kusi-Mensah, 2019).

We hypothesize that the variations in VET training systems can significantly affect earnings differences among self-employed and employed individuals receiving VET training (Åstebro & Chen, 2014; Hyytinen et al., 2013). Specifically, we posit that statist systems, with their emphasis on general skills, may result in an increased earnings gap for the self-employed. In contrast, collectivist systems, which endow individuals with specific, industry-vetted skills, may lead to a smaller earnings gap between employed and self-employed individuals.

To test this hypothesis, we conduct a correlational study using data from the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). Our sample includes 6924 participants from four countries representing collectivist (Czech Republic and Denmark) and statist (Finland and Norway) VET systems. We employ hierarchical ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to analyze the earnings gap between employed and self-employed individuals across these different VET systems.

Our results reveal a significant earnings gap between employed and self-employed individuals in statist systems, while no significant difference is observed in collectivist systems. These findings contribute to both the entrepreneurship literature and policy discussions in two important ways (Li et al., 2024; Cattaneo, 2024). First, they provide practical insights for policymakers on how to direct VET recipients toward successful employment and self-employment outcomes. Second, they address a gap in the entrepreneurship literature by distinguishing between institutional differences in VET systems and their impact on entrepreneurial outcomes.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: We begin with a detailed literature review on VET and entrepreneurship, followed by a thorough explanation of our theoretical framework and hypothesis development. We then describe our methodology, including data collection and analysis procedures. Next, we present our results and discuss their implications. We conclude with a summary of our findings, limitations of the study, and suggestions for future research.

Theoretical development and hypothesisVocational training is widely recognized as playing a critical role in preparing individuals for entrepreneurship by providing them with the necessary skills, knowledge, and mindset to start and manage their businesses (Chuan & Ibsen, 2022). Research has demonstrated that vocational training is associated with increased employment opportunities and higher earnings. Studies have shown that vocational training leads to increased employment opportunities and earnings (Doerr, 2022). Research conducted in Israel by Neuman and Ziderman (1999) demonstrated that vocational education at the high school level confers a significant labor market advantage, especially when students work in their specialized fields. In Singapore, Sakellariou (2003) found that technical education leads to higher returns compared to secondary education, with a particular emphasis on the advantages experienced by female workers. Agrawal and Agrawal (2017) showed that VET graduates in India enjoy lower unemployment rates and higher salaries than their counterparts with general secondary education. Germany has made significant progress by raising public awareness and recognition of advanced vocational qualifications, further enhancing VET's value (Wolter & Kerst, 2015).

Research has shown that vocational training positively influences entrepreneurial intentions (Buli & Yesuf, 2015; Galvão et al., 2018) and self-efficacy (Maritz & Brown, 2013). Individuals with vocational training are more likely to consider entrepreneurship a viable career option because it provides them with the necessary confidence, technical skills, and industry knowledge (Brockmann et al., 2008). Vocational training programs that include entrepreneurship education also positively impact individuals' entrepreneurial motivations (Tufa, 2021). Studies indicate that vocational training contributes to better business performance, survival rates, and growth prospects for the self-employed (Robb et al., 2014; Samoliuk et al., 2021). This is attributed to vocational training enhancing technical skills, managerial capabilities, and industry-specific understanding, leading to improved outcomes for vocational training graduates.

From a pedagogical standpoint, VET systems differ in their approaches to skill development and knowledge transfer. Collectivist systems often employ a dual learning model, combining classroom instruction with workplace-based learning (Deissinger, 2015). This approach aligns with situated learning theory, which posits that learning is inherently tied to authentic activity, context, and culture (Lave & Wenger, 1991). In contrast, statist systems tend to favor a more school-based approach, which may prioritize theoretical knowledge over practical application. These pedagogical differences can influence the development of both general and specific skills, potentially affecting graduates' ability to succeed in self-employment.

Entrepreneurship research has long recognized the importance of human capital in venture success (Unger et al., 2011). The type of skills developed through VET—whether more general or specific—can be viewed through the lens of human capital theory. Specific skills, more prevalent in collectivist systems, may provide a unique competitive advantage for self-employed individuals, allowing them to offer specialized services and products. General skills, emphasized in statist systems, while valuable for adaptability, may not provide the same level of differentiation in the market. This distinction is crucial when considering the potential earnings gap between employed and self-employed VET graduates (Backes-Gellner & Moog, 2013).

The political economy of skill formation, as articulated by Busemeyer and Trampusch (2012), provides a framework for understanding how different VET systems emerge and persist. Collectivist systems often arise in contexts where there is strong coordination between the state, employers, and labor unions, leading to a focus on industry-specific skills. Statist systems, on the other hand, typically develop in political contexts where the state takes a more central role in education and training, often with the goal of promoting social equality and mobility. These political-economic differences can have far-reaching effects on labor market outcomes, including the relative success of self-employed individuals (Thelen, 2004).

Hypothesis developmentThrough the lens of the comparative political economy approach, the effects of the two types of vocational training systems remain less explored in the entrepreneurship literature (Chuan & Ibsen, 2022). The collectivist approach to vocational education prioritizes community and societal needs, aiming to integrate individuals into a collective workforce that contributes to overall societal development. It emphasizes curriculum focus, cooperation, collaboration, apprenticeships, mentorships, and social responsibility. The curriculum is designed in consultation with employers, industry experts, and community representatives to align with the needs and priorities of the community. This approach fosters an environment of cooperation and collaboration among students, instructors, employers, and the broader community, promoting the sharing of knowledge, resources, and experiences. Apprenticeships and mentorship programs significantly transfer practical skills, knowledge, and values from experienced practitioners to students. Moreover, the collectivist approach strongly emphasizes social responsibility and cultivating a sense of duty, ethics, and civic mindedness among vocational education students.

In contrast, the statist approach to vocational education places significant emphasis on state control and central planning. It views vocational education as a means to achieve specific economic and political objectives. The state dominates in planning, implementing, and regulating vocational education. It determines the curriculum, identifies skills in demand, and allocates resources for vocational training programs. Standardization and certification of vocational qualifications are key features of this approach. National or state-level standards are often established to ensure individuals meet specific criteria to enter the workforce. The statist approach is often driven by workforce planning and economic development goals, with resources directed toward training programs in sectors or industries requiring skilled workers. Employment placement mechanisms, such as job fairs, recruitment agencies, and direct employment services, are commonly incorporated. Funding for vocational education programs is typically centralized and allocated by the government, enabling strategic allocation of resources to priority areas. In the traditional Hayekian sense, we expect the centralized approach in the statist system to be less conducive to self-employment earnings. The collectivist system with the higher engagement of stakeholders in governance and provision of training (Busemeyer & Schlicht-Schmälzle, 2014) may help provide the necessary skills for self-employment. Employers play a significant role in shaping the curriculum to align with their skill requirements and improve the specificity of vocational skills (Jensen & Rasmussen, 2019). In collectivist systems, intermediary organizations, such as employers' associations and trade unions, play an important role in governance, with training playing a more useful role in realizing firm-specific and industry-specific skills, and making the self-employed more competitive in earnings (Chuan & Ibsen, 2022). In contrast, statist systems typically integrate VET programs into the general upper-secondary school system. With minimal employer participation and apprenticeship opportunities, the resulting skills are considered limited in their general emphasis, with most training taking place within school settings.

The more hands-on training in areas such as carpentry, plumbing, hairstyling, graphic design, and culinary arts through employer and union involvement helps provide the necessary specific skills. Individuals can establish businesses that align with their vocational training and offer services and products within their area of expertise. Collectivist systems may provide a deeper understanding of the necessary mindsets and capabilities required to run a business. The broader, and more general skills under statist systems may not foster strong connections with industries and employers. This enables participants to gain practical experience through internships, apprenticeships, and cooperative education placements. Industry connections can provide valuable networking opportunities, mentorship, and exposure to real-world business environments. Such connections enhance participants' understanding of market dynamics and provide them with insights into the requirements and challenges of self-employment in their chosen industry.

Vocational and training programs for self-employment often emphasize flexibility and adaptability. They recognize the evolving nature of industries and markets and aim to equip participants with transferable skills that can be applied to a range of entrepreneurial ventures. This flexibility allows individuals to adapt their skills and business models to changing circumstances and seize emerging opportunities. Building on studies on vocational education and competencies (Brunello, 2001; Brunello & Rocco, 2017; Heijke et al., 2003), we contend that the narrower focus on firm- and occupation-specific skills in collectivist systems has a positive effect in closing the earnings gap under collectivist regimes of vocational training. Individual adaptability is stronger under the collectivist system because richer contextual knowledge allows individuals to meet the more challenging demands of self-employment. Though statist regimes have a greater emphasis on general education knowledge (Chuan & Ibsen, 2022), they may not impart the necessary specific knowledge to be successful in self-employment. Statist countries hold an advantage over collectivist VET countries in this regard due to their greater emphasis on general education subjects taught in schools. Based on this reasoning, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis

Among those with vocational educational training, a statist skills regime will lower income for the self-employed.

Sample and methodSampleTo test the proposed hypothesis, we use the latest release of the three rounds of The Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). The data includes 24 countries participating in Round 1 of the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) spanning from 1 August 1, 2011 to March 31, 2012. In Round 2, participants from 9 countries took part in data collection from April 2014 to March 2015. Finally, in Round 3, data collection took place between July and December 2017. As a comprehensive survey of adults (16 to 65 years) located in Europe, Asia (Korea and Japan), Israel, and Chile, PIAAC measures a variety of respondent characteristics, including cognitive skills, demographic, and work-related characteristics. A detailed description of the cognitive tests in PIACC is available in the OECD (2013). A rich collection of variables from a variety of countries allows us to test the effects of variations in skills regimes and returns to vocational training for the self-employed. Details on sampling and data collection procedures, along with the public use file employed in this study is available at https://www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/data/. The total sample consists of 230,691 participants from 36 countries.

To draw more precise estimates from a more comparable sample of participants, we only use respondents who reported their highest education as vocational training. We drop countries with mixed or liberal skills regimes because most participants do not exclusively have vocational education, and a variety of other opportunities could conflate the estimated effects of vocational training. Therefore, we restrict the sample to collectivist and statist systems and drop respondents from liberal or mixed-skill regimes. We only include individuals working 30 or more hours per week and those between the ages of 18 and 65. Based on case-wise deletion, the final sample consists of 6924 participants. The resulting sample represents four countries—the Czech Republic and Denmark (collectivist) and Finland and Norway (statist). This approach of focusing only on collectivist and statist systems is consistent with Chuan and Ibsen (2022). Table 1 provides descriptives by country.

MeasuresOur outcome measure is the log of monthly earnings including bonuses, corrected for purchasing power parity. Self-employment is operationalized using the question “Current work employee or self-employed” (1 = self-employed, 0 = employed). The statist/collectivist designation used in this study is based on Chuan and Ibsen (2022), the binary “collectivist and statist” (1–collectivist and 2–statist) referring to governance structures related to vocational educational training as systems driven by formal apprenticeship programs, public support for vocational training, or employer-controlled vocational education. These institutional differences in vocational training evolved over the 19th and 20th centuries and represent systematic variations in training for the labor force.

We include a variety of controls. We control for age, the square of age, sex (1–male; 2–female), number of people in the household, whether living with spouse or partner (1–yes; 2–no) and number of children. We control for cognitive ability as the balance in cognitive skills (Ganzach & Patel, 2018). We use the scores on the three cognitive skills in the PIAAC—literacy, numeracy, and problem solving, derived from computerized adaptive testing (CAT). The scores are based on the item response theory (IRT) measure and are reported as ten plausible values for each ability (Rutkowski et al., 2010) on a 500-point scale. We take the factor score of the three test scores. We control for the current state of health (1–excellent; 2–very good; 3–good; 4–fair; and 5–poor), parental education (neither parent has attained upper secondary; at least one parent has attained secondary; or at least one parent has attained tertiary) and language ability (1–native-born and native language, 2–native-born and foreign language, 3–foreign-born and native language, and 4–foreign-born and foreign language).

Next, we control for learning strategies using six items (1–not at all to 5–to a very high extent): (i) relate new ideas to real life; (ii) like learning new things; (iii) attribute something new; (iv) get to the bottom of difficult things; (v) figure out how different ideas fit together; (vi) looking for additional information. Cronbach's alpha was 0.80. We control for the index of learning at work and the index of readiness to learn, both controls provided by the PIAAC. We also include industry (isic4_c) and occupational (isco08_c) dummies. To control for correlation among the participants, we cluster standard errors by country.

ResultsTable 1 provides descriptives and correlations. To test the hypothesis, we use hierarchical ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. In Table 2, consistent with the entrepreneurship earnings puzzle self-employed have lower earnings (Model 2: β = −0.309, p < 0.05). The skill regime does not have an association with wages. The interaction between skill regime and self-employment is positive and significant (Model 4: β = 0.322, p < 0.01). Fig. 1 presents the plot where self-employed, relative to those employed, in statist regimes have a lower income. However, in collectivist skill regimes, there is no limited difference in earnings between self-employed and employed.

OLS estimates.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | ln_wage2 | ln_wage2 | ln_wage2 | ln_wage2 |

| Skill regime: Collectivist vs. Statists | −0.154 | −0.484⁎⁎ | ||

| (0.0666) | (0.103) | |||

| Self-employed | −0.309⁎⁎ | −0.371⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| (0.0665) | (0.00923) | |||

| Self-employed × Skill regime | 0.322⁎⁎⁎ | |||

| (0.0530) | ||||

| Age | 0.109⁎⁎⁎ | 0.110⁎⁎⁎ | 0.108⁎⁎⁎ | 0.110⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.0140) | (0.0142) | (0.0140) | (0.0142) | |

| Age-square | −0.00114⁎⁎⁎ | −0.00115⁎⁎⁎ | −0.00114⁎⁎⁎ | −0.00115⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.000164) | (0.000164) | (0.000164) | (0.000165) | |

| Sex | −0.262⁎⁎ | −0.272⁎⁎ | −0.262⁎⁎ | −0.271⁎⁎ |

| (0.0495) | (0.0537) | (0.0495) | (0.0544) | |

| People in Household | −0.0264 | −0.0243 | −0.0263 | −0.0242 |

| (0.0195) | (0.0201) | (0.0196) | (0.0201) | |

| Living with a spouse or partner | −0.140* | −0.142* | −0.140* | −0.143* |

| (0.0464) | (0.0466) | (0.0466) | (0.0469) | |

| Children | −0.0622 | −0.0601 | −0.0620 | −0.0595 |

| (0.0449) | (0.0442) | (0.0449) | (0.0444) | |

| Cognitive ability | 0.0945* | 0.0938* | 0.0945* | 0.0930* |

| (0.0358) | (0.0344) | (0.0358) | (0.0346) | |

| Health-state | −0.0525⁎⁎ | −0.0520⁎⁎ | −0.0527⁎⁎ | −0.0527⁎⁎ |

| (0.0156) | (0.0156) | (0.0156) | (0.0154) | |

| At least one parent has attained second (ref. Neither parent has attained upper secondary) | −0.0111 | −0.00921 | −0.0108 | −0.00934 |

| (0.0376) | (0.0383) | (0.0375) | (0.0384) | |

| At least one parent has attained tertiary | −0.0166 | −0.0145 | −0.0169 | −0.0153 |

| (0.0163) | (0.0165) | (0.0165) | (0.0171) | |

| Interactions between the place of birth and language status | −0.00136 | −0.00290 | −0.00167 | −0.00298 |

| (0.0167) | (0.0165) | (0.0165) | (0.0165) | |

| Learning strategies | 0.0939 | 0.0854 | 0.0938 | 0.0881 |

| (0.0907) | (0.0954) | (0.0908) | (0.0959) | |

| Index of Learning at Work | 0.0532 | 0.0550 | 0.0533 | 0.0547 |

| (0.0233) | (0.0235) | (0.0232) | (0.0237) | |

| Index of Readiness to learn | −0.0524 | −0.0464 | −0.0524 | −0.0475 |

| (0.0694) | (0.0724) | (0.0696) | (0.0728) | |

| Industry dummies | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Occupational dummies | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Standard errors clustered by | country | country | country | country |

| Constant | 6.043⁎⁎⁎ | 6.348⁎⁎⁎ | 6.079⁎⁎⁎ | 6.442⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.385) | (0.334) | (0.381) | (0.385) | |

| Observations | 6924 | 6924 | 6924 | 6924 |

| R-squared | 0.452 | 0.456 | 0.452 | 0.457 |

Standard errors in parentheses.

When examining the earnings gap between vocationally trained employees and self-employed individuals using PIAAC data, the absence of significant effects for additional analysis by moderators such as cognitive ability, learning strategies, readiness to learn, age, and sex can provide several logical insights:

PIAAC data includes measures of cognitive abilities, such as literacy and numeracy skills. PIAAC data also captures information on learning strategies, including problem-solving and information-processing skills. PIAAC data allows for the assessment of individuals' readiness to learn, which reflects their motivation and willingness to acquire new knowledge and skills. Age and sex are two additional heterogeneities to consider in explaining the earnings gap.

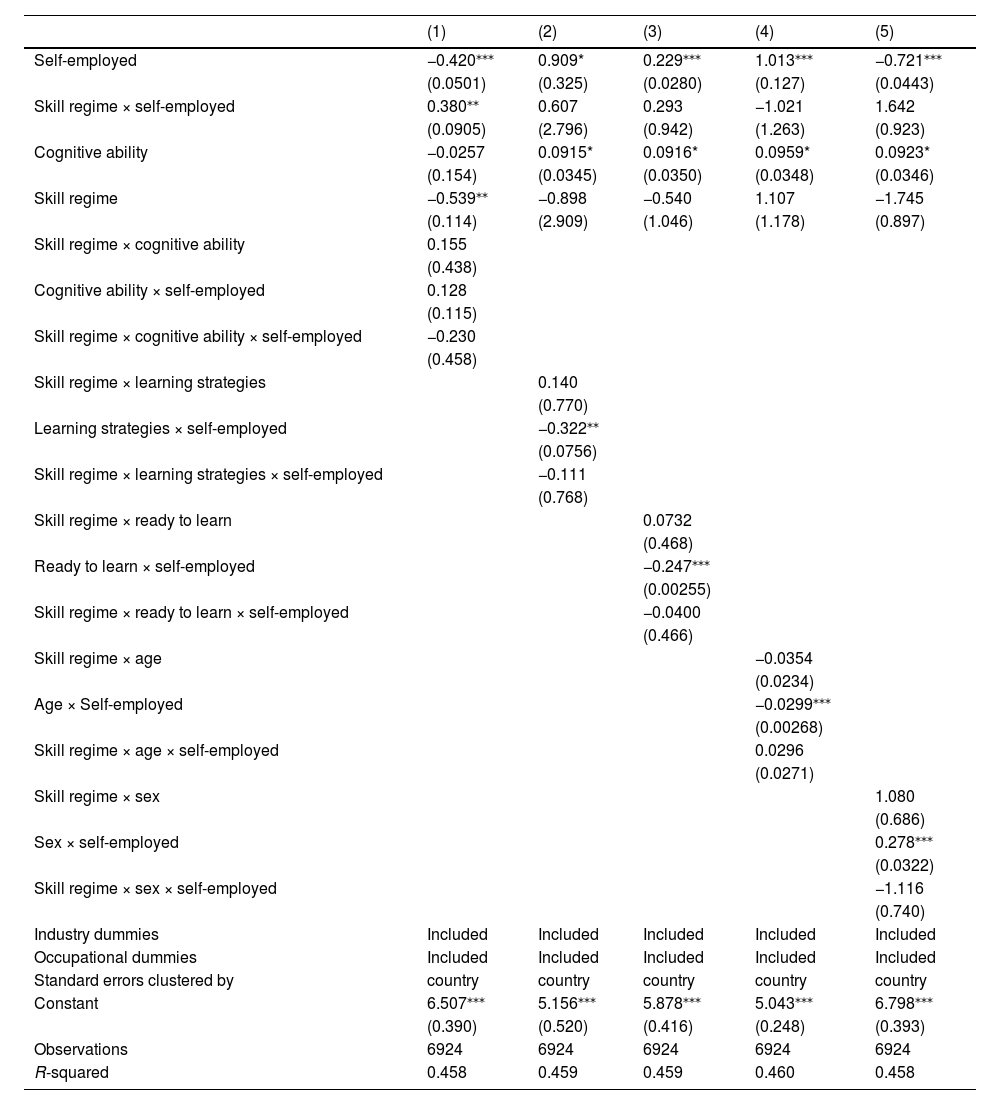

Exploring heterogeneity in effects across these factors can provide further insights into the complex dynamics shaping earnings disparities in this specific population. In Table 3, additional analysis by moderators of cognitive ability (model 1), learning strategies (model 2), readiness to learn (model 3), age (model 4), or sex (model 5) did not affect earnings.

Additional analysis.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-employed | −0.420⁎⁎⁎ | 0.909* | 0.229⁎⁎⁎ | 1.013⁎⁎⁎ | −0.721⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.0501) | (0.325) | (0.0280) | (0.127) | (0.0443) | |

| Skill regime × self-employed | 0.380⁎⁎ | 0.607 | 0.293 | −1.021 | 1.642 |

| (0.0905) | (2.796) | (0.942) | (1.263) | (0.923) | |

| Cognitive ability | −0.0257 | 0.0915* | 0.0916* | 0.0959* | 0.0923* |

| (0.154) | (0.0345) | (0.0350) | (0.0348) | (0.0346) | |

| Skill regime | −0.539⁎⁎ | −0.898 | −0.540 | 1.107 | −1.745 |

| (0.114) | (2.909) | (1.046) | (1.178) | (0.897) | |

| Skill regime × cognitive ability | 0.155 | ||||

| (0.438) | |||||

| Cognitive ability × self-employed | 0.128 | ||||

| (0.115) | |||||

| Skill regime × cognitive ability × self-employed | −0.230 | ||||

| (0.458) | |||||

| Skill regime × learning strategies | 0.140 | ||||

| (0.770) | |||||

| Learning strategies × self-employed | −0.322⁎⁎ | ||||

| (0.0756) | |||||

| Skill regime × learning strategies × self-employed | −0.111 | ||||

| (0.768) | |||||

| Skill regime × ready to learn | 0.0732 | ||||

| (0.468) | |||||

| Ready to learn × self-employed | −0.247⁎⁎⁎ | ||||

| (0.00255) | |||||

| Skill regime × ready to learn × self-employed | −0.0400 | ||||

| (0.466) | |||||

| Skill regime × age | −0.0354 | ||||

| (0.0234) | |||||

| Age × Self-employed | −0.0299⁎⁎⁎ | ||||

| (0.00268) | |||||

| Skill regime × age × self-employed | 0.0296 | ||||

| (0.0271) | |||||

| Skill regime × sex | 1.080 | ||||

| (0.686) | |||||

| Sex × self-employed | 0.278⁎⁎⁎ | ||||

| (0.0322) | |||||

| Skill regime × sex × self-employed | −1.116 | ||||

| (0.740) | |||||

| Industry dummies | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Occupational dummies | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Standard errors clustered by | country | country | country | country | country |

| Constant | 6.507⁎⁎⁎ | 5.156⁎⁎⁎ | 5.878⁎⁎⁎ | 5.043⁎⁎⁎ | 6.798⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.390) | (0.520) | (0.416) | (0.248) | (0.393) | |

| Observations | 6924 | 6924 | 6924 | 6924 | 6924 |

| R-squared | 0.458 | 0.459 | 0.459 | 0.460 | 0.458 |

Standard errors in parentheses.

Through the political economy lens, our article shows that the earnings gap is significant in more centralized statist systems and non-significant for collectivist regimes of vocational training. Our article contributes to entrepreneurship literature by highlighting the value of specific knowledge imparted to self-employment under collectivist systems and statist systems exacerbating the gap. Moreover, the effects do not vary across demographic or skill-based heterogeneities.

Our findings reveal significant differences in earnings gaps between employed and self-employed individuals across collectivist and statist vocational education systems. To understand these differences, we turn to human capital theory (Becker, 1964) and institutional economics (North, 1990).

In collectivist systems, such as those in the Czech Republic and Denmark, the non-significant earnings gap between employed and self-employed individuals can be attributed to the specific human capital developed through close industry involvement in VET. As Lazear (2004) argues, entrepreneurs benefit from a balanced skill set. The apprenticeship-style training common in collectivist systems may provide this balance, combining theoretical knowledge with practical, industry-specific skills. This specific human capital can be particularly valuable in self-employment, allowing individuals to offer specialized services or identify unique market opportunities (Unger et al., 2011). Conversely, the larger earnings gap observed in statist systems like Finland and Norway may be explained by the emphasis on general skills in these VET programs. While general skills enhance adaptability (Hanushek et al., 2017), they may not provide the specific expertise that can differentiate self-employed individuals in the market. This aligns with Gimeno et al.'s (1997) threshold model of entrepreneurial exit, suggesting that specific human capital can lower the performance threshold for continuing an entrepreneurial venture.

From an institutional perspective, the variations in earnings gaps reflect the broader economic systems in which these VET programs are embedded. Collectivist systems, with their coordinated market economies (Hall & Soskice, 2001), foster closer ties between education and industry. This institutional arrangement may create a more supportive environment for self-employment, with better-aligned skills and stronger industry networks. In contrast, the more liberal market approach of statist systems may provide less structured support for the transition from VET to self-employment. These findings underscore the importance of considering both the type of human capital developed through VET and the institutional context in which this training occurs when examining self-employment outcomes. They suggest that the success of self-employed VET graduates is not solely a function of individual skills, but also of how well these skills align with the institutional and economic environment.

Our study contributes to the ongoing debate about the role of specific versus general skills in entrepreneurial success (Lazear, 2004). The smaller earnings gap in collectivist systems supports the value of specific skills for self-employed individuals, aligning with Gimeno et al.'s (1997) threshold model of entrepreneurial exit. This model suggests that specific human capital can lower the performance threshold for continuing an entrepreneurial venture. Moreover, our findings extend the varieties of capitalism framework (Hall & Soskice, 2001) to entrepreneurship outcomes. The differential effects of collectivist and statist systems on self-employment earnings suggest that institutional arrangements in skill formation have far-reaching consequences beyond traditional employment.

For policymakers, our results highlight the potential benefits of involving employers and industry stakeholders in VET curriculum design, particularly for fostering successful self-employment. This aligns with recent policy trends towards 'New Apprenticeship' models that aim to combine the benefits of work-based and school-based learning (Fuller & Unwin, 2011). For educators and VET institutions, our findings underscore the importance of integrating specific, industry-relevant skills into curricula, even in more state-led systems. This could involve increased collaboration with local businesses or the integration of more applied projects into coursework. The implications of our results are significant for policy-making, as they identify the differences in political economies of vocational training that affect earnings gaps among employed and self-employed. By recognizing the importance of the nature of skill development driven by collectivist vs. statist systems, policymakers can develop strategies to enhance outcomes from self-employment. By shedding light on variations in vocational education systems and their impact on the entrepreneurial earnings gap, the offering insights into the design of effective vocational training programs.

Limitations of the study include its limited generalizability as it focused on specific countries with unique vocational education systems. The findings do not establish causality, and other factors may contribute to earnings gaps. Future research should employ longitudinal studies, expand the comparative analysis to include more countries, examine specific factors within vocational education systems, explore mediating variables, and consider policy implications. These research directions would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between vocational education systems and earnings gaps, aiding in the development of policies and interventions to promote equity in employment and entrepreneurship.

Our study has several limitations that provide avenues for future research. First, our analysis is cross-sectional, limiting causal inferences. Longitudinal studies could provide insights into how earnings gaps evolve over time. Second, while we controlled for various factors, unmeasured variables such as individual motivation or regional economic conditions could influence our results. Future research could incorporate these factors.

Additionally, our study focused on four countries. Expanding the analysis to a broader range of countries could provide more nuanced insights into how different VET systems affect entrepreneurial outcomes. Future research could also explore potential mediating factors, such as the role of social networks or access to capital, in explaining the link between VET systems and self-employment earnings. Finally, qualitative studies could complement our quantitative findings by providing in-depth insights into how VET graduates perceive and utilize their skills in self-employment contexts. As countries continue to grapple with youth unemployment and the changing nature of work, understanding how different VET systems influence both employment and self-employment outcomes becomes increasingly crucial. Our study provides a stepping stone for further research in this important area.

This study provides evidence that the political economy of vocational education systems significantly influences the earnings gap between employed and self-employed individuals. Collectivist systems, with their emphasis on specific skills and employer involvement, appear to better equip individuals for successful self-employment.

CRediT authorship contribution statementPankaj C. Patel: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Pejvak Oghazi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.