This study attempts to find out the impact of organizational justice on the innovative work behavior of employees working in Chinese telecommunication sector, while analyzing the mediating role of knowledge sharing between the independent and dependent variables of this study. In order to test the study hypotheses, a data of 345 respondents working in Chinese telecommunication industry was collected. Confirmatory factor analysis suggested a good model fit, while structural equation model provided significant and positive effect of organizational justice on the employee innovative work behavior and knowledge sharing. Knowledge sharing mediated the relationship between organizational justice and employee innovative work behavior. Managerial and practical implications of the study are also provided.

In past few decades, the importance of how organizations should treat their employees has increased manifold. Patterson (2001) suggested that organizations should serve as platforms for individuals rather than only individuals serving as resources for organizations. The logic behind this preposition relies on the fact that individuals react as per how they are treated. Recently, organizational justice (OJ) has become a wide spread concern for many researchers. Organizational behavior and Organizational Theory realm suggested organizational justice as a crucial concept and organizational practice in modern organizational management (Chen et al., 2015). Due to the widespread efforts for, not only soliciting organizational justice for employees but also sustaining it throughout the organization resulted in vigorous importance of organizational justice in organizational structure and culture (Karkoulian, Assaker, & Hallak, 2016). This is not only important for the wellbeing of individual employees but also for organizations themselves. Improve organizational justice may have a direct and positive effect on the performance and sustainability of any organization (Karkoulian et al., 2016). In past, number of research studies have supported a positive relationship between higher level of organizational justice and job satisfaction, job commitment, positive work attitudes and behaviors (Chen et al., 2015; Dundar & Tabancali, 2012; Silva & Caetano, 2014). On the other hand, lower level of organizational justice is related with negative effects such as stress, poor employees’ psychological well-being, employee turnover, retaliatory intentions etc. (Silva & Caetano, 2014). Fair treatment with employees is important for organizations for encouraging employees to innovate products, services and procedures. In fact firms and nations are progressively rallying on the technical skills of their employees for innovation (Agarwal, 2014). According to Global Innovation Index’ (GII) report (2013), regardless of the difficult conditions in global economy, dynamic innovation hubs are getting multiplied all around the world. Therefore, continuous innovation has become a dire organizational source for organizational survival; as a result, organizations are highly interested in investigating those factors that may impact innovative work behavior (Agarwal, 2014) such as organizational justice.

One major possibility for organizations to become more innovative is to encourage its employees’ innovative work behavior (Agarwal, 2014). However, innovative work behavior is very difficult to achieve if employees are not treated fairly.

Not only, organizational justice is an important element in defining innovative work behavior of employees but also the knowledge that is required to innovate products, services and business policies etc. Therefore, it seems righteous claim that innovation is related with knowledge and knowledge sharing with in organizations. Number of studies about knowledge management and organization confirmed that employee knowledge sharing improves organizational performance such as innovation capability and absorptive capacity (e.g. Liao, Fei, & Chen, 2007; Liu & Phillips, 2011; Yesil & Dereli, 2013). As knowledge sharing is considered a key element in organizational competitiveness and growth, therefore, not sharing knowledge might impede organizational survival (Lin, 2007). This advocates that in the presence of organizational fairness, sharing the right knowledge enhances the chances of innovative behavior and encourages employees to be more innovative. A number of studies have investigated the “why” and “how” aspects of organizational justice and determined its positive and negative impacts on employees (Ouyang, Sang, Li, & Peng, 2015). It can be inferred that positive perceptions about the organizational justice leads to positive behavior and actions (Jakopec & Susanj, 2014). However, previous studies lack their focus on additional and important forms of organizational justice, such as temporal and spatial justice (Colquitt, 2001; Usmani & Jamal, 2013). This suggests that organizational justice is a multi-dimensional phenomenon, rather than a uni-directional factor. Further, numerous studies have been conducted to explore the phenomena of organizational justice and its implications in western context, however, little has been done in eastern countries. Particularly, China is a quickly transforming country from plan economy to market economy and becoming the innovation oriented business hub of the world (Bessant, 2016). The 13th Chinese government 5 years plan for 2016–2020 also supports the claim of higher innovation orientation of Chinese organizations. Organizational justice researchers suggested the need to enquire the phenomena in telecommunication sector along with pharmaceutical, education, cement and textile industry (Usmani & Jamal, 2013).

Chinese Telecommunication sector is one among other sectors that is expanding and growing both nationally and internationally (China outlook, 2015). However, the innovative expansion of telecommunication sector needs internal motivation of employees that may be affected by numbers of factors such as organizational justice and knowledge sharing level of the employees. Therefore, the current study intents to enhance the understanding about employee innovative work behavior (EIWB) by examining the impact of organizational justice and knowledge sharing on employee innovative work behavior. Moreover, it investigates the mediating role of knowledge sharing between organizational justice and employee innovative work behavior. This study contributes to the body of knowledge both theoretically and practically. Theoretically, it is the first attempt to include two new dimensions of organizational justice (temporal and spatial justice) into the model of organizational justice. Second, it investigates the combine impact of these five organizational justice forms on the innovative work behavior of employees working in Chinese telecommunication sector. Third, it attempts to study the impact of knowledge sharing on the innovative work behavior. Fourth, it provides a mediation analysis, where knowledge sharing mediates the relationship between organizational justice and employee innovative work behavior. Finally, it provides some practical and managerial implications, study limitations and future research suggestions.

Literature reviewOrganizational justice (OJ)Organizational literature provides considerable attention to the phenomenon of organizational justice. It suggests that in the creation of organizational culture, organizational justice plays an important role in shaping the behavior of organizational members (Ouyang et al., 2015). The notion of fairness is the foundation of Equity Theory that has been widely applied in organizational behavior field (Chen et al., 2015). The concept of organizational justice is based on Equity Theory which is extracted from the concept of justice or fairness. Organizational justice is mainly defined as the employees’ perceptions about the degree of fairness with which they are treated by organizational authorities (Whitman, Caleo, Carpenter, Horner, & Bernerth, 2012). Theoretically, three forms of organizational justice are widely mentioned in organizational research literature namely distributive, procedural and interactional justice (Karkoulian et al., 2016). First, distributive justice is defined as the degree to which organizational leaders may distribute promotions or financial rewards among employees. It is primarily established on the pillars of Equity Theory (Adams, 1965). It relates to individuals’ perceived fairness about the outcomes that they receive. It is the anticipation of individuals about the receiving outcomes that based on their work related efforts and organizational contributions (Rio-Lanza, Vazquez-Casielles, & Diaz-Martin, 2009). When assessing distributive justice, comparisons of inputs from employees (effort) and outcomes from organization (Salary, appreciation. performance appraisal etc.) are used as evaluation base (Whitman et al., 2012). Second, perceived fairness of individuals about all the procedures used while making employees’ related decisions (Lin & Hsieh, 2010; Thibaut & Walker, 1975) is known as perceived organizational justice. It relates to those procedures that managers opt for distributing outcome and also reaction of employees towards the fairness of those particular procedures (Tyler, 1987). Third, interactional justice is known as the fairness of communication of decisions and organizational procedures (Bies & Moag, 1986; Gelens, Dries, Hofmans, & Pepermans, 2013). It focuses on fairness perception of individuals related to communication and interpersonal treatment that they receive from their organization (Ambrose, 2002). It defines their perception of the fair treatment of organizational authorities regarding decisions within organization (Palaiologos, Papazekos, & Panayotopoulou, 2011). However, these three forms, due to not encompassing all justice area, are not enough explanation of the complex phenomenon of organizational justice. Therefore, literature proposes the need to explore further forms of organizational justice, such as temporal justice and spatial justice (Usmani & Jamal, 2013).

This study contributes to existing literature by including temporal and spatial justice in its theoretical framework. Although, research literature comprises of numerous studies related to organizational justice, however, most of these studies have focused on distributive, procedural and interactional justice forms of organizational justice. Nonetheless, for better understanding of the phenomenon, many researchers insisted to explore further forms of organizational justice (Colquitt, Conlon, Wesson, Porter, & Ng, 2001). Therefore, to fill this gap in literature, two additional dimensions of organizational justice namely temporal justice and spatial justice are also included in theoretical framework of present study (Usmani & Jamal, 2013). Temporal justice stands on the foundation of Social Justice Theory. Temporal justice is defined as “having discretionary control over one’s own time” (Goodin, 2010). It is a matter of how much discretionary power one has over his or her time (Akram, Haider, & Feng, 2016; Usmani & Jamal, 2013). Having plenty of time suggests that a person have more choices about how he/she can spend his/her time and fewer constraints in utilizing that time freely. This provides individuals with the sense of unique fairness related to their personal time and job related time. Its uniqueness is argued because time in itself is a resource and therefore, it should not be considered as a part of distributive justice rather should be taken as separate form of organizational justice (Usmani & Jamal, 2013). It may have its own implications for individuals in the organizations. Finally, spatial justice is defined as “having to do with space” (Hawker, 2006; Usmani & Jamal, 2013), it is a” focused and deliberate emphasis on the geographical and spatial aspects of the justice” (Usmani & Jamal, 2013) and it the perception related to “appropriateness of distance” and it encompasses “resource distance” and also “Budget allocation discrimination” among organizational masses including different branches.

Knowledge sharing (KS)More recently, the dependency of businesses has increased on their knowledge asset that comes in the form of their employees (Safa & Solms, 2016). Currently, businesses and nations are depending on the competitive knowledge that helps them to prosper and survive (Lin, 2007; Yesil & Dereli, 2013). Today, the economy has become more knowledge based; therefore, knowledge is referred as a basic element of competition, survival and growth for organizations and even for nations (Lin, 2007; Xinyan & Xin, 2006). Organizations, whether large or small, might gain a competitive advantage on the basis of the expertise, skills and integrated knowledge of their employees and use them in their daily business practices (Hu, Horng, & Sun, 2009). Practically, not only sharing the knowledge but also converting it into practice is the norm today. Moreoever, organizations are playing the role of “knowledge-integrating institutions”. This integration of knowledge from different people and groups takes place in the process of producing goods as well as services (Ibragimova, Ryan, Windsor, & Prybutok, 2012). According to Xinyan and Xin (2006), knowledge sharing is the significant method to obtain and create knowledge in the work place. It is the core element of knowledge management (Park, Son, Lee, & Yun, 2009) and for successful knowledge management initiatives; knowledge sharing plays crucial role (Wang & Noe, 2010).

Therefore, it suggests that when used in daily organizational activities, knowledge serves the role of a competitive advantage for that organization. Knowledge is defined as the “information processed by individuals including ideas, facts, expertise and judgments relevant for individual, team, and organizational performance” (Alavi & Leidner, 2001; Bartol & Srivastava, 2002; Wang & Noe, 2010). On the other hand, knowledge sharing is known as the “provision of task information and know-how to help others and to collaborate with others to solve problems, develop new ideas or implementing policies or procedures” (Cummings, 2004). According to Grant (1996), knowledge sharing is the content and it captures the bi-directionality and the frequency of knowledge flow among co-workers. According to Goh and Sandhu (2014), knowledge sharing is different from knowledge exchange (knowledge sharing and knowledge seeking) and knowledge transfer (knowledge sharing by the source of knowledge and acquisition and application by the knowledge recipient). Knowledge sharing is multi-directional process that involves donor and collector of knowledge. Therefore, it is not only collecting the knowledge but also donating the knowledge to others. In present study, knowledge sharing is defined as knowledge donating and knowledge collecting. Knowledge donating is defined as “the communication based upon a person’s own wish to transfer his/her intellectual capital”, whereas, knowledge collecting is known as” an attempt to persuade other individuals to share their intellectual capital or what they know” (van den Hooff & De Ridder, 2004). These both processes are distinct and active processes in nature as knowledge donating is engaged in active communication with others in order to transfer knowledge, whereas; knowledge collecting is consulting others for the purpose of encouraging them to share their intellectual capital (Alhady, Idris, Sawal, Azmi, & Zakaria, 2011; Yesil & Dereli, 2013). According to Alhady et al. (2011) the organization that supports its employees for contributing knowledge (within groups and organizations) is expected to create new and better ideas and encourage new business opportunities, hence enabling organizational innovation activities.

Employee innovative work behavior (EIWB)According to Janssen (2004), highly competitive environment requires innovation as it can lift the competitiveness at all levels (individual, group and organizational levels). Innovation is defined as “a process through which economic or social value is extracted from knowledge. It happens through the creation, diffusion and transformation of knowledge to produce new or significantly improved products or processes that are then place to use by society” (Raykov, 2014). Innovative work behavior, on the other hand, is defined as “intentional development, introduction and application of new ideas inside a job role, group or organization for suitable role of the group or organizational performance (Momeni, Ebrahimpour, & Ajirloo, 2014). Another definition of innovative work behavior is provided as “an intentional generation, promotion and realization of novel ideas in the workplace” (Janssen, 2000; Scott & Bruce, 1994; West & Farr, 1989). This definition presents three basic functional elements of innovative work behavior namely creation, promotion and implementation of novel ideas that benefit the organizations (Janssen, 2000, 2004; Scott & Bruce, 1994; Yuan & Woodman, 2010). Idea generation stage may include all those considerations that aimed at refining new products, organizational practices and services. This stage is greatly affected by the motivation level of employees. Idea promotion stage provides strength to those generated ideas and strives to remove organizational resistance and barriers to bring change (Shane, 1994). This stage requires stronger organizational support and collaboration. Finally, the idea realization stage helps in bringing the generated and promoted ideas into practical reality and results into the development of new products, services and job procedures (Janssen, 2000). Many studies have suggested that in rapidly changing world employee innovative work behavior serves as a sustainable competitive advantage for organizations that provides the firms with long term survival and success (Abstein & Spieth, 2014). This indicates a continuous, dedicated and sincere effort on the behalf of organizational employees and the maintenance of such dedicated efforts need special attention of organizational management (Agarwal, 2014). In fact, EIWB is prone to number of organizational factors such as organizational justice and knowledge sharing. Such factors may enhance or reduce EIWB.

The relationship between organizational justice, knowledge sharing and employee innovative work behaviorRaykov (2014) stated that innovative work behavior is the predetermining factor for organizational survival and competitiveness in global economy. Employee innovative work behavior is a personal driven motivational behavior (Shih & Sustanto, 2011), therefore, it is expected that organizational justice, if present, may become an element of this motivational process that affects innovative work behavior (Pieterse, van Knippenberg, Schippers, & Stam, 2009). It can be argued that organizational justice is an important motivational factor that directs employees to demonstrate a particular behavior or not (Kerwin, Jordan, & Turner, 2015). The review of literature suggested that when employees perceive they are not treated fairly by their organization, their conscious obligation towards organization is affected negatively and their performance and positive attitude towards work tends to decline (Silva & Caetano, 2014). Number of studies investigated organizational justice impact on the innovation and innovative work behavior (Dundar & Tabancali, 2012; Silva & Caetano, 2014). However, a comprehensive organizational justice model was lacking. Additionally, the mediating role of knowledge sharing between organizational justice and EIWB is not studied previously. Janssen (2004) examined the moderating role of perceived distributive and procedural justice between the relationship of innovative work behavior and stress. He found a positive relationship between innovative work behavior and stress when the level of perceived distributive justice and perceived procedural justice were low. Recently, Momeni et al. (2014) invested the effect of inferential organizational justice on innovative work behavior by using four factor model of organizational justice. They found a strong correlation between distributive, procedural, interpersonal, informational justice and innovative work behavior. However, temporal justice and spatial justice were not a part of their analysis. Additionally, Almansour and Minai (2012) explored the relationship between organizational justice and innovative work behavior in Jordan’s government sector. They found that only interactional justice have a direct and significant relationship with employee innovative work behavior, whereas, distributive and procedural justice established insignificant relationship with EIWB. Further, Kim and Lee (2013) found the effect of organizational justice (3 factor model) on the organizational commitment and innovative work behavior in virtual organizations. They suggested a direct and significant relationship between organizational justice and innovative work behavior. They authors also found a significant mediating effect of organizational commitment between organizational justice and EIWB.

Previous studies suggested that beside organizational justice, knowledge sharing has also been a strong contributor in employee innovative work behavior (Kuo, Kuo, & Ho, 2014; Lu, Lin, & Leung, 2012). Knowledge, being the most important organizational resource, allows the novel organizational results such as innovation (Kamasak & Bulutlar, 2010; Kogut & Zander, 1996; Smith, Collins, & Clark, 2005). Knowledge is referred as the main building block for the innovation process in organizational literature. Number of studies has shown that knowledge management is crucial for improving organizational performance (e.g. Choi, Poon, & Davis, 2008; Perez-Arostegui, Benitez-Amado, & Tamayo-Torres, 2012) and the knowledge sharing and innovativeness of workers in the organization (Kuo et al., 2014). An excellent knowledge management system requires free knowledge sharing in the form of donating and collecting knowledge. Therefore, knowledge sharing not only allows employees to pass the knowledge to other workers but it also enables others to obtain valuable knowledge (Kuo et al., 2014), that facilitate in the generating, promoting and implementing novel ideas. Knowledge sharing is suggested to help individuals to expand their individual knowledge range and increase their problem solving ability and work output quickly (Hu et al., 2009). Positive energy, in the form of knowledge sharing, decreases the negative effects of bad work environment and leads to innovative work behavior (Clercq, Dimov, & Belausteguigoitia, 2014). Therefore, in a knowledge intensive era; knowledge sharing is crucial learning strategy for higher innovative performance (Lu et al., 2012). Review of the literature suggested that those employees who are having higher education and knowledge, they have the ability to directly influence the organizational capacity for implementing innovation (Evans & Waite, 2010; Raykov, 2014). However, the question that what role does the knowledge sharing plays in generating innovative work behavior is still an under explored phenomena.

This is particularly true for the emerging Asian economies like China that is focusing heavily on service industry growth through innovation. Lu et al. (2012) investigated the effects of learning goal orientation on individual innovative work performance with knowledge sharing as the mediator in a survey from 248 employees and their supervisors from diverse industries in China. They found a positive significant effect of learning goal orientation and a significant mediating role of knowledge sharing. Focusing on knowledge donating and knowledge sharing, Kamasak and Bulutlar (2010) explored the effects of knowledge sharing on innovation. Using multiple regression analysis, they found positive and significant effect of knowledge collecting on all types of innovation; however, knowledge donating was found to have no effect on exploratory innovation. For current study, researchers considered knowledge sharing as a combination of knowledge donating and knowledge collecting.

Although knowledge sharing have many benefits, people are generally found reluctant to share their knowledge easily (Lu et al., 2012). One potential reason of such reluctance can be perceived organizational injustice. When employees feel that they are not treated fairly by their organizations, lack of trust arises between organization and its members. Therefore, employees become reluctant to share their knowledge with other members of the organization, ultimately affecting the innovative activities within organization. According to Lu et al. (2012), as compared to general or routine performance or work behavior, innovative work behavior is more difficult due to three reasons. First, current practices do not prescribe the methods or procedures involved in innovative performance, as organization does not provide any specific guideline for generating, promoting and realizing new ides (Janssen, 2004). Second, innovative initiatives may raise criticism by those who resist change and are conservative (Lu et al., 2012). Third, innovative behavior brings a chance of failure with it and therefore, it is considered risky. This suggests that innovative work behavior is heavily dependent on the cooperation and support from co-workers and management in terms of knowledge and fair treatment. The fair treatment is required in the form of distributive, procedural, interactional, temporal and spatial justice respectively. In other words, if employees perceive that they are treated fairly, in terms of outcome, procedures, interactional communications about decision making, time and resources, they are expected to be more encouraged to depict innovative work behavior in their organizations. For freely generating, promoting and finally realizing innovative ideas, innovative work behavior requires acknowledgement and appreciation of the actions taken by innovative employees. Additionally, knowledge sharing is key to success for employees at each and every stage of innovative work behavior. When employees are able to freely share knowledge by donating as well as collecting it from other co-workers in their organization, they are more motivated to generate, share, promote and implement their innovative ideas. This is true for those employees who receive fair treatment and can easily collect and donate knowledge, are more attached to their organizations psychologically and tends to contribute in achieving organizational goals more effectively through better performance and work behaviors (Pignata, Winefield, Provis, & Boyd, 2016; Somech & Drach-Zahavy, 2004).

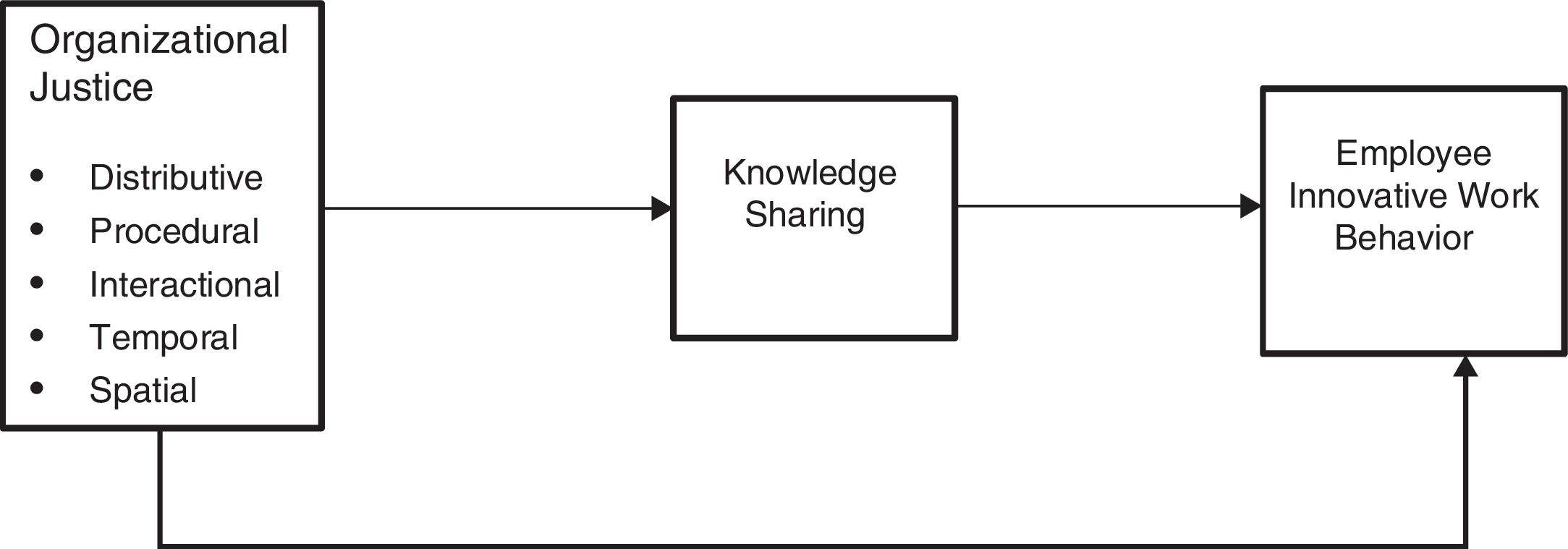

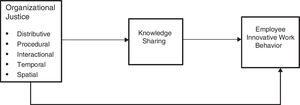

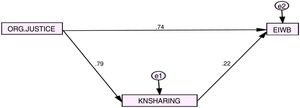

A more logical and theoretical base for the propositions of current study is provided by Social Exchange Theory. Social Exchange Theory proposed by Blau (1964) suggested that generally individuals seek to reciprocate to those who provide them some benefit. This kind of reciprocation creates discretionary obligation on their behalf to respond positively and provide back something more valuable in response (Saks, 2006). This reciprocal behavior occurs in work settings where employees perceive fair treatment (in the form of distributive, procedural, interactional, temporal and spatial justice) from their organization and thus they tend to show better work behavior (such as innovative work behavior) in return (Pignata et al., 2016). The effect of positive perceptions about distributive, procedural, interactional, temporal and spatial justice on employee innovative work behavior is mediated by incorporating knowledge sharing as a mediator. On the basis of the above literature, research gap and arguments following hypotheses are generated and Fig. 1 presents the diagrammatic representation.

H1: Positive perceptions of employees about organizational justice effects EIWB positively and significantly.

H2: Positive perceptions of employees about organizational justice effects knowledge sharing positively and significantly.

H3: knowledge sharing among co-workers effects EIWB positively and significantly.

H4: Knowledge sharing mediates the relationship between organizational justice and EIWB.

MethodologyProcedure and participantsIn order to find out the relationship between the independent and dependent variables of the study, employees working in the Shanghai telecommunication sector of China were requested to fill up the questionnaire. Due to the non-accessibility to all employees’ data bases, convenient sampling technique was used to collect the data from these employees. In total 450 questionnaires were distributed among employees with clear instructions about how to fill up the questionnaire. However, final collection of the questionnaires resulted in the generation of 345 useable questionnaires for testing the hypotheses of current study. This provides the researchers with an acceptable percentage (77%) of the questionnaires to apply statistical tests on this data. Out of 345 respondents, 184 were male and 161 were female respondents. The age range of these participants was from 18 years to 50 years or above. Initial screening of the data also suggested that most of these employees were having a work experience of 5 years to 15 years.

Questionnaire designIn order to validate the propositions made in this research study, a five point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) was developed. Three dimensions of organizational justice, i.e. distributive, procedural and interactional justice items were adapted from the scale of Al-Zu’bi (2010). These three dimensions comprises of 5, 5 and 9 items respectively. Additionally, two dimensions of organizational justice, temporal and spatial justice were adapted from Usmani and Jamal (2013). These dimensions comprise of 4 and 3 items respectively. Overall Alpha reliability of organizational justice scale was reported as .872 by Usmani and Jamal (2013). Further, based on Van den Hooff and Van Weenen (2004), knowledge sharing was measured by adapting the scale of Lin (2007). Knowledge donating with three items reported an Alpha reliability of 0.78, while, knowledge collecting with four items and Alpha reliability of 0.80 in previous studies (Goh & Sandhu, 2014; Lin, 2007; Yesil & Dereli, 2013). For measuring employee innovative work behavior, a 9 item validated scale adapted from Janssen (2000). Janssen (2000) reported an Alpha value of 0.94 in his study. The final questionnaire for present study comprised of 42 items. For maximizing the response rate and for the better understanding of Chinese respondents, this questionnaire was translated into Chinese language.

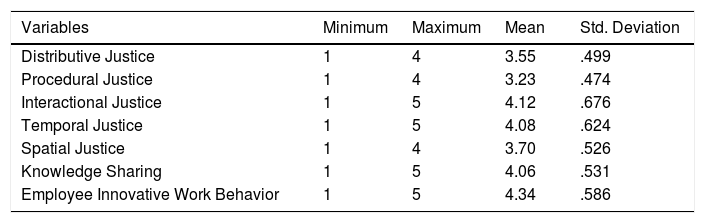

Results and analysisDescriptive analysisIn order to analyze the nature of the data and variables, descriptive statistics were conducted. Table 1 presents the values of minimum, maximum, mean and standard deviation from these analyses.

Descriptive Statistics (n=345).

| Variables | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distributive Justice | 1 | 4 | 3.55 | .499 |

| Procedural Justice | 1 | 4 | 3.23 | .474 |

| Interactional Justice | 1 | 5 | 4.12 | .676 |

| Temporal Justice | 1 | 5 | 4.08 | .624 |

| Spatial Justice | 1 | 4 | 3.70 | .526 |

| Knowledge Sharing | 1 | 5 | 4.06 | .531 |

| Employee Innovative Work Behavior | 1 | 5 | 4.34 | .586 |

According to Bagozzi and Yi (1991), common method biasness is the “variance that is attributed to the measurement method rather than to the construct of interest”. Being a potential validity threat for research findings (Jones, 2009), it is important to test for common method biasness prior to testing hypotheses of the study. Therefore, researchers tested common method biasness through Harman’s single factor test method (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). This test provides the evidence that the data of present study is free from common method bias. The total variance explained by one factor loading is 47%, which is less than the 50% (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

Content and face validityContent and face validity was ensured by translating the questionnaire into the language that the respondents can understand and interpret clearly. For an accurate translation, back translation method was used. Respondents were guided with clear instructions to provide their response to questionnaires. Additionally, the use of double barreled questions, and confusing or unfamiliar terms was also avoided in the self-administered questionnaire of present study. All these cautions are very important for ensuring the face and content validity of any instrument used in research studies (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, & Podsakoff, 2012). It is also important that respondents should be ensured about the anonymity of their responses; therefore, researchers guaranteed complete anonymity to respondents.

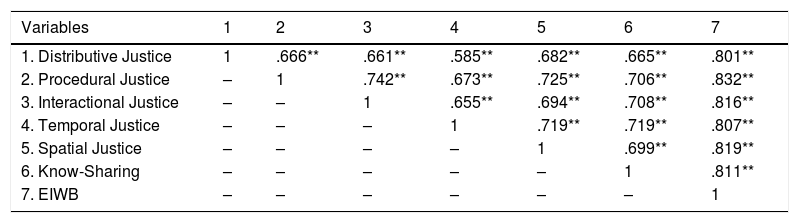

Convergent validityCorrelation analysis explains the convergent validity of any study. Therefore, the strength and the nature of the relationship between independent, dependent and mediating variables of the study were assessed through correlation analysis. Results from Pearson Product Moment correlation are provided in Table 2. Correlation analysis suggested a strong and positive correlation between all variables of the study at p=0.01 significant level. Distributive justice is positively and strongly related to knowledge sharing (r=.655***, n=345, p<0.00) and employee innovative work behavior (r=.801***, n=345, p<0.00). Procedural justice is positively and strongly related to knowledge sharing (r=.706***, n=345, p<0.00) and employee innovative work behavior (r=.832***, n=345, p<0.00). Interactional justice is positively and strongly related to knowledge sharing (r=.706*8**, n=345, p<0.00) and employee innovative work behavior(r=.816***, n=345, p<0.00), temporal justice is positively and strongly related to knowledge sharing (r=.719***, n=345, p<0.00) and employee innovative work behavior(r=.801*7**, n=345, p<0.00), and finally spatial justice is also positively and strongly correlated with knowledge sharing (r=.699**, n=345, p<0.00), and employee innovative work behavior(r=.819**, n=345, p<0.00). Further, knowledge sharing indicated a positive and strong correlation with employee innovative work behavior (r=.811**, n=345, p<0.00). Beside independent, dependent and mediating variables, all independent variables were also positively and moderately correlated with each other.

Pearson product Moment Correlation Analysis of the variables of study (n=345).

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Distributive Justice | 1 | .666** | .661** | .585** | .682** | .665** | .801** |

| 2. Procedural Justice | – | 1 | .742** | .673** | .725** | .706** | .832** |

| 3. Interactional Justice | – | – | 1 | .655** | .694** | .708** | .816** |

| 4. Temporal Justice | – | – | – | 1 | .719** | .719** | .807** |

| 5. Spatial Justice | – | – | – | – | 1 | .699** | .819** |

| 6. Know-Sharing | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | .811** |

| 7. EIWB | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 |

**Correlation is significant at 0.01 level (2-tailed).

*Correlation is significant at 0.05 level (2-tailed).

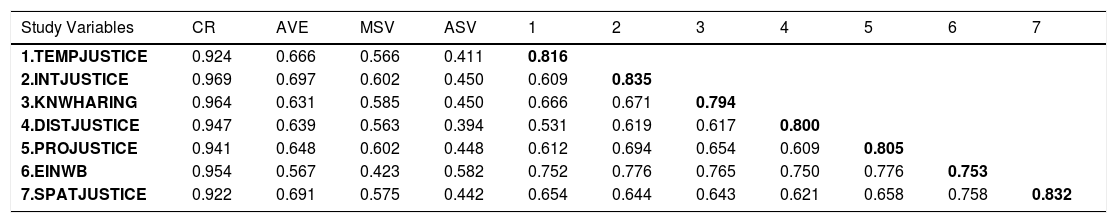

In Table 3, additional information about the convergent validity is reported along with discriminant validity. Convergent validity is evident from all values of average variance explained (AVE) above than 0.5. Inter-item reliability is evident from composite reliability (CR) values above than 0.7. Additionally, the square root of average variance explained is greater than any inter-factor correlation present in Table 3. This suggests awesome discriminant validity of study results (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Discriminant validity for the variables of the study (n=345).

| Study Variables | CR | AVE | MSV | ASV | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.TEMPJUSTICE | 0.924 | 0.666 | 0.566 | 0.411 | 0.816 | ||||||

| 2.INTJUSTICE | 0.969 | 0.697 | 0.602 | 0.450 | 0.609 | 0.835 | |||||

| 3.KNWHARING | 0.964 | 0.631 | 0.585 | 0.450 | 0.666 | 0.671 | 0.794 | ||||

| 4.DISTJUSTICE | 0.947 | 0.639 | 0.563 | 0.394 | 0.531 | 0.619 | 0.617 | 0.800 | |||

| 5.PROJUSTICE | 0.941 | 0.648 | 0.602 | 0.448 | 0.612 | 0.694 | 0.654 | 0.609 | 0.805 | ||

| 6.EINWB | 0.954 | 0.567 | 0.423 | 0.582 | 0.752 | 0.776 | 0.765 | 0.750 | 0.776 | 0.753 | |

| 7.SPATJUSTICE | 0.922 | 0.691 | 0.575 | 0.442 | 0.654 | 0.644 | 0.643 | 0.621 | 0.658 | 0.758 | 0.832 |

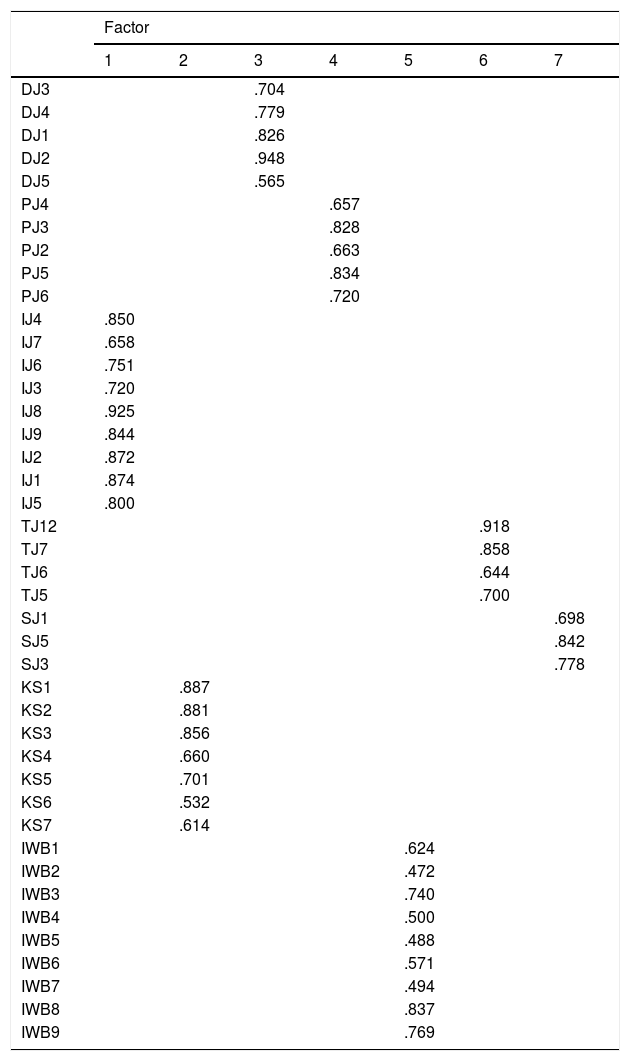

The construct validity is tested through exploratory factor analysis in IBM SPSS 21. For factor extraction, Maximum Likelihood Method was applied that resulted in the generation of 7 factors. Further observation of the EFA results indicated that Kaiser–Myer–Olkin value of .964 was greater than the minimum suggested value of 0.6 (Kaiser, 1974), Bartlett’s Test of spehericity was significant at 0.000 p value (Bartlett, 1954) and finally 7 extracted factors have the Eigen values greater than 1. A cumulative variance explained was 66.047% with loadings above 0.3 (Pallant, 2013). Table 4 presents results of pattern matrix from EFA.

Pattern Matrix for 7 extracted variables of the study (345).

| Factor | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| DJ3 | .704 | ||||||

| DJ4 | .779 | ||||||

| DJ1 | .826 | ||||||

| DJ2 | .948 | ||||||

| DJ5 | .565 | ||||||

| PJ4 | .657 | ||||||

| PJ3 | .828 | ||||||

| PJ2 | .663 | ||||||

| PJ5 | .834 | ||||||

| PJ6 | .720 | ||||||

| IJ4 | .850 | ||||||

| IJ7 | .658 | ||||||

| IJ6 | .751 | ||||||

| IJ3 | .720 | ||||||

| IJ8 | .925 | ||||||

| IJ9 | .844 | ||||||

| IJ2 | .872 | ||||||

| IJ1 | .874 | ||||||

| IJ5 | .800 | ||||||

| TJ12 | .918 | ||||||

| TJ7 | .858 | ||||||

| TJ6 | .644 | ||||||

| TJ5 | .700 | ||||||

| SJ1 | .698 | ||||||

| SJ5 | .842 | ||||||

| SJ3 | .778 | ||||||

| KS1 | .887 | ||||||

| KS2 | .881 | ||||||

| KS3 | .856 | ||||||

| KS4 | .660 | ||||||

| KS5 | .701 | ||||||

| KS6 | .532 | ||||||

| KS7 | .614 | ||||||

| IWB1 | .624 | ||||||

| IWB2 | .472 | ||||||

| IWB3 | .740 | ||||||

| IWB4 | .500 | ||||||

| IWB5 | .488 | ||||||

| IWB6 | .571 | ||||||

| IWB7 | .494 | ||||||

| IWB8 | .837 | ||||||

| IWB9 | .769 | ||||||

Extraction Method: Maximum Likelihood.

Rotation Method: Promax with Kaiser Normalization.

a. Rotation converged in 7 iterations.

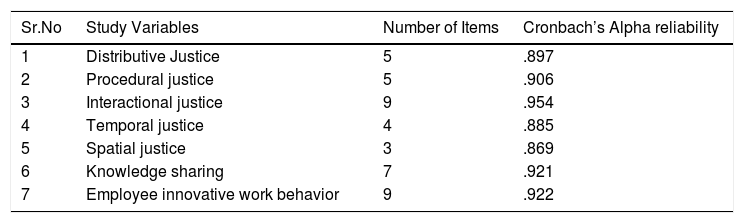

Although researchers adapted previously validated and reliable scales for present study, however, the revalidation for the reliability of these scales was very important. Therefore, Cronbach’s Alpha reliability test was conducted using IBM SPSS. Table 5 provides the Alpha reliability values for distributive, procedural interactional, temporal and spatial justice and knowledge sharing and EIWB. All measures resulted in higher Cronbach’s Alpha reliability and authenticate the previous reliability claims of researchers. The Cronbach’s Alpha value of 0.6 or higher is considered as a reliability proof for scale and suggests its acceptability for use in study (Pallant, 2013). Since the Alpha values of present study measures are all higher than 0.6, they were found reliable to test the hypotheses of this study.

Cronbach’s Alpha reliability analysis (n=345).

| Sr.No | Study Variables | Number of Items | Cronbach’s Alpha reliability |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Distributive Justice | 5 | .897 |

| 2 | Procedural justice | 5 | .906 |

| 3 | Interactional justice | 9 | .954 |

| 4 | Temporal justice | 4 | .885 |

| 5 | Spatial justice | 3 | .869 |

| 6 | Knowledge sharing | 7 | .921 |

| 7 | Employee innovative work behavior | 9 | .922 |

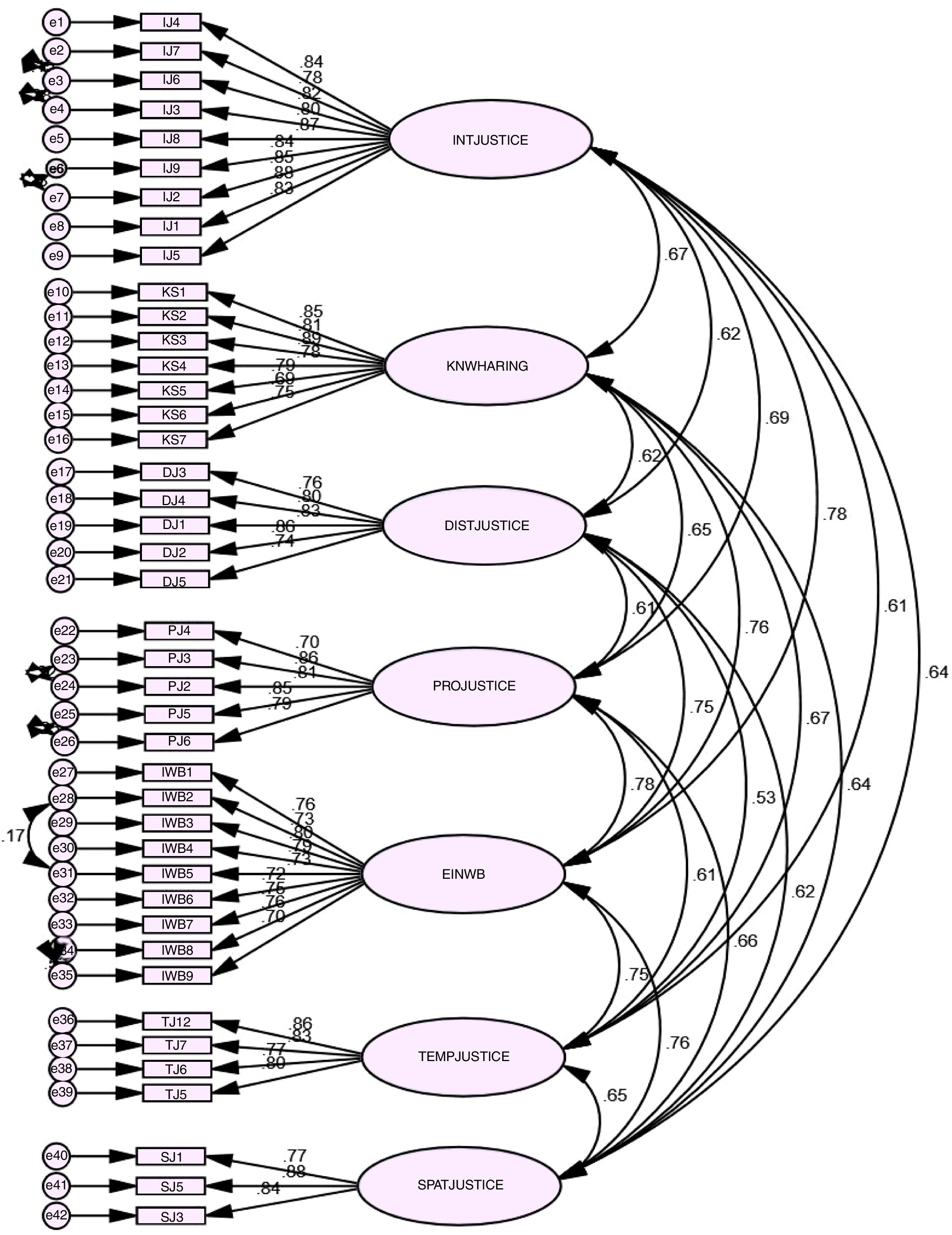

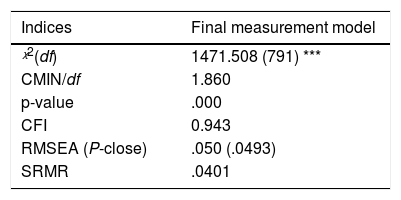

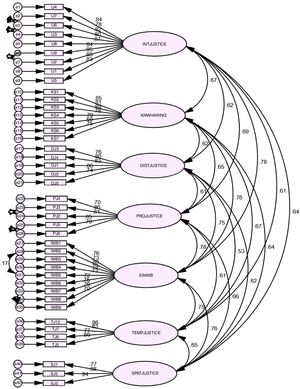

The purpose of the CFA model is to explain the relationship between latent variables and measured variables (Byrne, 2012). Keeping this purpose in mind, researchers conducted CFA by using 7 loaded factors of distributive, procedural, interactional, temporal and spatial justice, knowledge sharing and employee innovative work behavior with 42 finally loaded items. For a better authentication of the study model, this test is explained with a combination of model fit indices including Chi-Square test, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI) and standardized root mean square of residual (SRMR). These particular measurement indices were focused due to their superiority over other fit indices. These indices are insensitive to sample size and misleading parameter estimates (Kline, 2005). Goodness of fit indices of the final model is provided in Table 6 and CFA model is depicted in Fig. 2. The CFA results indicate that the data fits the measurement model very well. The value of CMIN/df is 1.86 that lies under the threshold of 2. Further, the comparative fit index (CFI) value is 0.943, which is higher than the suggested value of 0.9 (Hu & Bentler, 1999), indicating an excellent model fit. Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) provides a value of .050 that is lower than 0.07 threshold (Steiger, 1990). Additionally, the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) is .0513 that is lower than the suggested threshold value of 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Hence, these good fit values of measurement model provide the basis for testing the hypotheses of this study in next section.

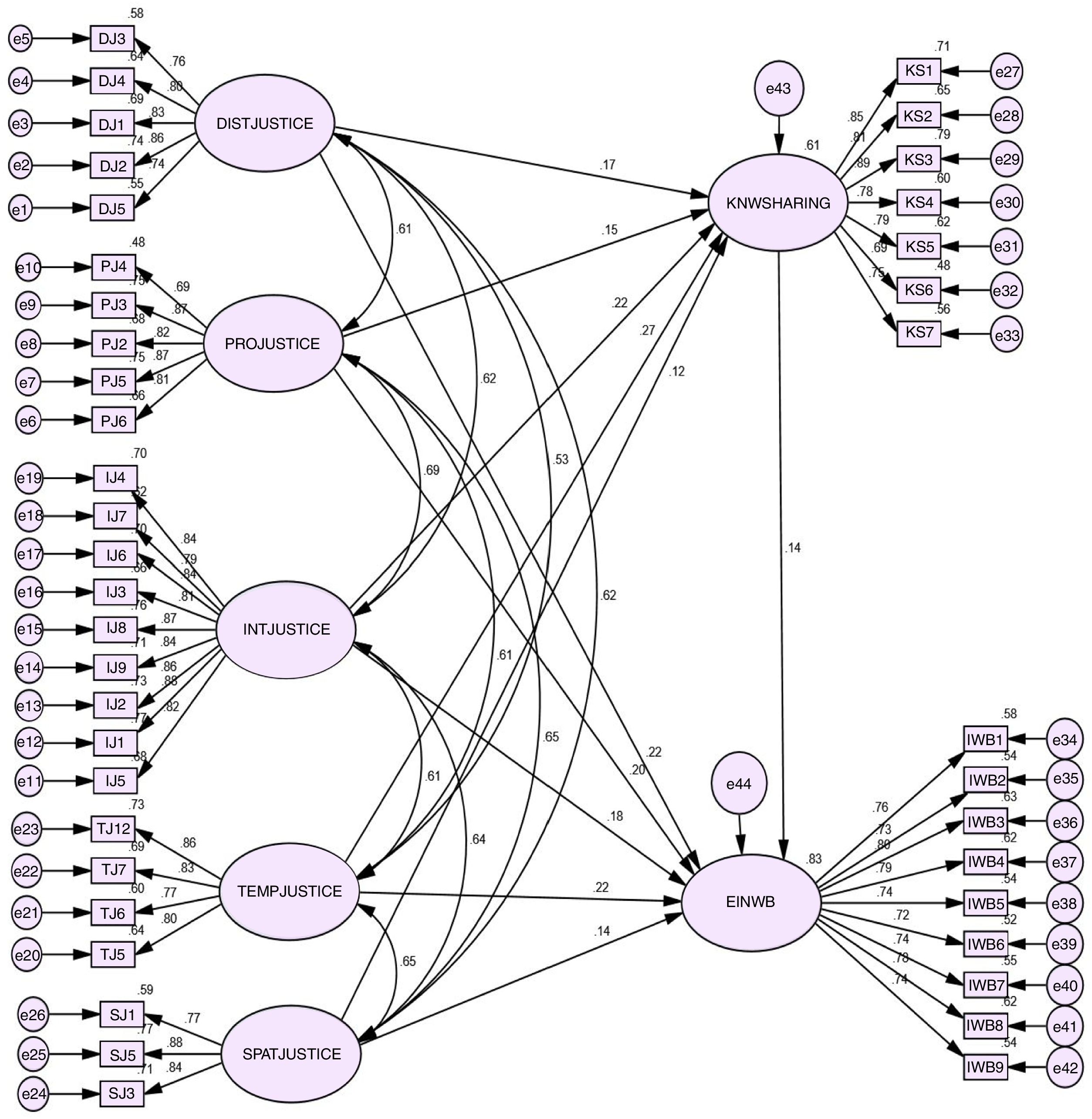

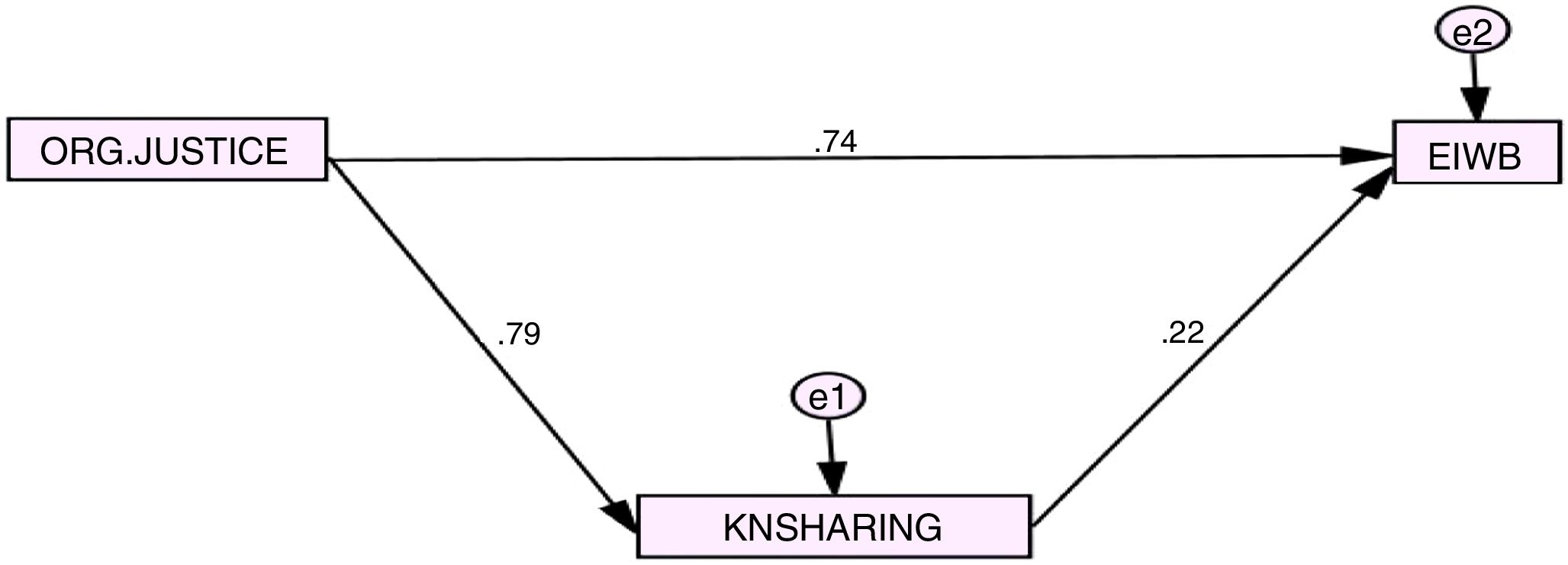

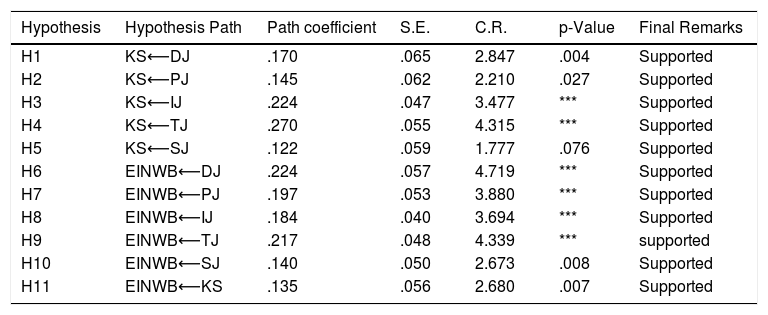

For testing the hypotheses of this study, SEM analysis was conducted by using Amos 21. Regression path values, standardized regression weights, critical ratios (C.R), standard errors (S.E), probability values (p) and acceptance/rejection of the hypotheses are provided in Table 7. Final SEM model is provided in Fig. 3. SEM results suggested a significant and positive effect of distributive (β=.170; p<0.004), procedural (β=.145; p<0.027), interactional (β=.224; p<0.000), temporal (β=.27; p<0.000) and spatial justice (β=.122; p<0.076) on knowledge sharing. The positive and significant effect of distributive (β=.224; p<0.000), procedural (β=.197; p<0.000), interactional (β=.184; p<0.013), temporal (β=.217; p<0.000) and spatial justice (β=.140; p<0.008) on employee innovative work behavior is also evident form the results of the SEM. Knowledge sharing also found effecting employee innovative work behavior positively and significantly ((β=.135; p<0.007). R2 is .83 for the final model that suggests, overall a very good fit (Fig. 4).

SEM Direct Effects.

| Hypothesis | Hypothesis Path | Path coefficient | S.E. | C.R. | p-Value | Final Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | KS⟵DJ | .170 | .065 | 2.847 | .004 | Supported |

| H2 | KS⟵PJ | .145 | .062 | 2.210 | .027 | Supported |

| H3 | KS⟵IJ | .224 | .047 | 3.477 | *** | Supported |

| H4 | KS⟵TJ | .270 | .055 | 4.315 | *** | Supported |

| H5 | KS⟵SJ | .122 | .059 | 1.777 | .076 | Supported |

| H6 | EINWB⟵DJ | .224 | .057 | 4.719 | *** | Supported |

| H7 | EINWB⟵PJ | .197 | .053 | 3.880 | *** | Supported |

| H8 | EINWB⟵IJ | .184 | .040 | 3.694 | *** | Supported |

| H9 | EINWB⟵TJ | .217 | .048 | 4.339 | *** | supported |

| H10 | EINWB⟵SJ | .140 | .050 | 2.673 | .008 | Supported |

| H11 | EINWB⟵KS | .135 | .056 | 2.680 | .007 | Supported |

Source: Authors’ estimations.

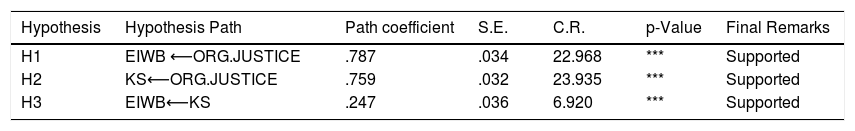

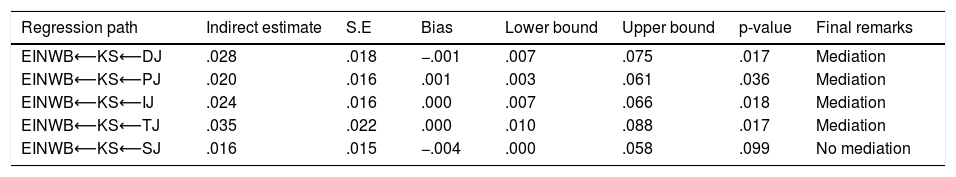

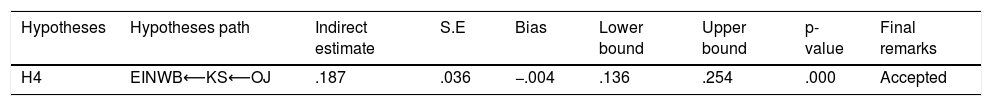

For testing the mediation effects of knowledge sharing, the bootstrapping technique was used in AMOS 21. According to Preacher and Hayes (2008) bootstrapping is “a nonparametric resampling procedure and it does not impose the assumption of normality of the sampling distribution. It is an intensive computational method that involves repeatedly sampling from the data set and estimate the indirect effect in each resampled data set. This repeatness occurs thousands times and results in an empirical approximation of the sampling distribution of ab is built and used to construct confidence intervals for the indirect effect”. In present study, bootstrapping was done by taking 2000 resamples and 90% confidence interval level (Mackinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004). The results supported mediation role of knowledge sharing between distributive, procedural, interactional and temporal justice and employee innovative work behavior. However, it was found that knowledge sharing does not mediate between spatial justice and EIWB. Details of mediation analysis are provided in Table 9. Overall, it was found that knowledge sharing mediates between organizational justice and employee innovative work behavior. The results of main hypothesis about mediation are provided in Table 10.

Mediation analysis DOJ, POJ, IOJ, TOJ, SOJ, KS & EIWB.

| Regression path | Indirect estimate | S.E | Bias | Lower bound | Upper bound | p-value | Final remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EINWB⟵KS⟵DJ | .028 | .018 | −.001 | .007 | .075 | .017 | Mediation |

| EINWB⟵KS⟵PJ | .020 | .016 | .001 | .003 | .061 | .036 | Mediation |

| EINWB⟵KS⟵IJ | .024 | .016 | .000 | .007 | .066 | .018 | Mediation |

| EINWB⟵KS⟵TJ | .035 | .022 | .000 | .010 | .088 | .017 | Mediation |

| EINWB⟵KS⟵SJ | .016 | .015 | −.004 | .000 | .058 | .099 | No mediation |

Source: Authors’ estimation.

The intention to conduct this study was to find out the impact of five forms of organizational justice on the innovative work behavior of employees working in the Chinese telecommunication sector. The main hypotheses of the study were “positive perceptions of employees about organizational justice effects EIWB positively and significantly” (H1), “positive perceptions of employees about organizational justice effects knowledge sharing positively and significantly (H2), “knowledge sharing among co-workers effects EIWB positively and significantly” (H3), and “knowledge sharing mediates the relationship between organizational justice and EIWB (H4)”. It was also intended to test for the mediating role of knowledge sharing between distributive, procedural, interactional, temporal and spatial justice and innovative work behavior. The CFA model provided a very good model fit for proposed model. Further, the hypotheses of this study were tested by using structural equation modeling. The results of structural equation modeling justified that if employees have a positive perception about distributive, procedural, interactional, temporal and spatial justice; they will tend to display more positive work behavior and will be more involved in generating new ideas, discussing those ideas to peers and materializing them by practically implementing them in the organization. This supports the claims of previous researchers (Almansour & Minai, 2012; Janssen, 2000; 2004; Kim & Lee, 2013; Momeni et al., 2014). This study suggests that around 23% of the variation in employee innovative work behavior is resulted due to the distributive justice. While temporal justice explains around 22% variance in employee innovative work behavior, procedural, interactional and spatial justice explained 20%, 18.4% and 14% variance in employee innovative work behavior respectively. The highest impact of distributive justice and temporal justice explains that for Chinese employees, it’s more important to have fairness in distribution of financial and other work related rewards following with temporal fairness to have more discretionary control over one’s own time. Further, procedural justice and interactional justice also have a fair contribution in the innovative work behavior of such employees. This indicates that fairness of procedures used in organizational decision making and fairness of communicating these decisions effectively in organization are important contributor in the employee innovative work behavior. However, as compare to distributive, procedural, interactional and temporal justice, spatial justice was found a least contributor but still a significant variable that brings variation in employee innovative work behavior. Further, the results suggested that temporal justice results in highest variation in knowledge sharing with 27%, following with interactional, distributive, procedural and spatial justice with 22.4%, 17%, 14.5% and 12.2% respectively, confirming with previous researchers (Kamasak & Bulutlar, 2010; Lu et al., 2012). Additionally, knowledge sharing contributed 13.5% variance in the employee innovative work behavior (Kamasak & Bulutlar, 2010). All these regression paths were significant and therefore, provide bases to test mediation between independent and dependent variables the results are provided in Table 8. Mediation paths from distributive, procedural, interactional, temporal and spatial justice to knowledge sharing and then to employee innovative work behavior suggested that knowledge sharing mediates the relationship between distributive, procedural, interactional and temporal justice and employee innovative work behavior. However, these results do not provide the evidence for the proposition that knowledge sharing mediates the relationship between spatial justice and employee innovative work behavior. Finally, for testing the main hypotheses of the study, the model provided a significant impact of organizational justice on EIWB. The overall effect of organizational justice on EIWB is 78.7% at p value of 0.000, therefore, H1 is accepted. Organizational justice was found having a positive and significant impact on the KS with 75.9% with p-value of 0.000, leading to the acceptance of H2 of the study. Further, with 24.7% and at p-value of 0.000, knowledge sharing has also implied a significant and positive impact on the EIWB, hence directing for the acceptance of H3 of this study. Lastly, with a value of 18.7% and at p level 0.00, knowledge sharing mediated the relationship between organizational justice and EIWB, thus H4 is also accepted.

ConclusionOn the basis of literature review, this study proposed that positive perception of the employee about distributive, procedural, interactional, temporal and spatial justice contribute positively in the employee innovative work behavior. Overall, organizational justice implied a positive and significant impact on the employee innovative work behavior. Due to the collectivist social system, and importance of families, work units and tribes, the need to recognize the importance of organizational justice in generating innovative work behavior is particularly important for eastern countries (Usmani & Jamal, 2013). Moreover, it was also proposed that knowledge sharing mediates the relationship between organizational justice and employee innovative work behavior. The results have also supported this proposition. It is suggested in this study that not only the existing forms of organizational justice are important but also some new and untapped organizational justice forms are worth investigating. Further, beside organizational justice, knowledge sharing plays a key role in generating innovative work behavior. It also mediates the relationship between distributive, procedural, interactional and temporal justice and employee innovative work behavior. Hence, the role of organizational justice and knowledge sharing in generating innovative work behavior of the employees should not be neglected and needs special attention.

Practical and managerial implicationsThis study has a number of practical and managerial implications. First of all it suggested the importance of studying and investigating the role of different forms of organizational justice in investigating employee innovative work behavior. Historically, only distributive, procedural and interactional organizational justice were considered important elements of organizational justice. This study highlights two relatively new but important forms of organizational justice and their role in generating employee innovative work behavior and knowledge sharing. Particularly, temporal justice was found a prominent contributor in knowledge sharing and employee innovative work behavior (along with distributive, interactional and procedural justice) in Chinese telecommunication industry. Therefore, this study suggests that managers should pay specific attention towards temporal justice along with distributive, procedural and interactional justice. The concept of temporal justice can be implemented efficiently when assigning projects and tasks and deciding work hours and when providing work deadlines to employees. This will help in stress management in employees and they will be more productive and innovative during work hours. This may help the Chinese organizations to increase the level of knowledge sharing among staff members and also improve their level of innovative work behavior. Providing employees with spatial justice, will ensure that employees don’t waste their energy and time in accessing resources rather spend their time more efficiently. To reduce the sense of budgetary discrimination, resources should be allocated among employees, according to their needs throughout the organization, hence making the use more efficient. Next, this study suggests that knowledge sharing contributes in the innovative work behavior of organizational employees and it also mediates the effect of organizational justice on innovative work behavior; therefore, it is important that knowledge sharing should be facilitated in the form of not only donating but also collecting knowledge. Knowledge sharing results in a cooperative and healthy work environment that generates innovative ideas and also facilitates effective implementation of those ideas. Management should encourage communication between employees on regular basis. Formal communication in the form of group discussions and informal communication in the form of socialization will facilitate effective knowledge sharing among organizational employees.

Study limitations and future research suggestionsThis study is not free from some limitations. First, the sample was selected on convenience bases. Only those employees were included in this study who showed their consent to fill up the questionnaire. However, future studies may use some other forms of sample selection technique such as random probability sampling technique. Second, present study is referred as cross sectional study; therefore, this may limit its ability to inaugurate a certain causal relationship between all variables. Although, the researchers reinforced the directionality of this study in hypotheses through organizational justice, knowledge sharing and employee innovative work behavior theories, however, in future, longitudinal study is suggested for the better establishment of causal relationship between the variables of the study. It is also suggested that the role of these forms of organizational justice and knowledge sharing in generating employee innovative work behavior (particularly temporal and spatial justice) may further investigated in the context of other organizations. This investigation may encompass other Asian countries which are progressively developing.