Innovative capabilities are important for firms to maintain competitive advantages. To develop such capabilities, firms can utilize from existing knowledge, skills and markets (i.e., exploitation) and/or gain from new ones (i.e., exploration). Although previous research has discussed about the impact of exploitative capability (EXC) and explorative capability (ERC) on firm performance, the effects of portfolios of such capabilities remain largely unexplored. Therefore, in this study, to investigate how firms’ EXC and ERC portfolios influence performance, we develop a framework through which to examine their congruence and incongruence effects on firm performance. Using panel data of China's listed firms from 2012 to 2017, we extracted EXC and ERC by using stochastic frontier analysis and further investigated their (in-)congruence effects via response surface analysis. Our results reveal that, compared with incongruence, the congruence between EXC and ERC positively influences firm's performance. Furthermore, in the case of congruence, the higher both capabilities are, the higher firm performance will be. In the case of incongruence, the combination of high ERC and low EXC outperforms the opposite. These conclusions shed new light on how to better invest and develop both EXC and ERC for firms’ innovation.

Environmental variations and fierce market competition encourage firms to build and enhance sustained competitive advantages via innovation (Tidd, 2001; Tushman & O'Reilly, 2002; Damanpour & Schneider, 2006). According to the Resource-Based View (RBV), firms must innovate by developing, integrating and reconfiguring their capabilities (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997). Exploitation and exploration are the two main types of innovative capabilities applied by firms in response to survival and competitive pressures (Yalcinkaya, Calantone & Griffith, 2007; Lisboa, Skarmeas & Lages, 2011; Sheng & Hartmann, 2019). Exploitation primarily focuses on existing knowledge, skills, processes and markets, whereas exploration emphasizes new knowledge, technologies, skills, markets, and products (March, 1991). According to a report from the Boston Consulting Group (BCG), firms that can arrange their exploitative and explorative capabilities well sustain increased performance levels when facing dynamic environments and fierce competition (BCG, 2019).

Although previous research has discussed the relationship between ambidexterity (i.e., exploitation and exploration) and firm performance, research gaps in both content and methodology remain. On the one hand, prior research regarding the influence of exploitation and exploration on firm performance has not reached a consensus: some scholars have concluded that the relationship between exploitation, exploration, and performance is linear (Uotila, Maula, Keil & Zahra, 2009; Josephson, Johnson & Mariadoss, 2016), whereas others have regarded it as non-linear (Luo, Kumar, Mallick & Luo, 2018). In addition, the direction of such impact varies in previous research (Atuahene-Gima, 2005; Lisboa et.al, 2011; Sarkees, Hulland & Chatterjee, 2014). Furthermore, despite the fact that most current scholars agree that firms can simultaneously build exploitative capability (EXC) and explorative capability (ERC), past research on the relationship between EXC and ERC remains limited as to their balanced and combined (i.e., interaction) effects (Cao, Gedajlovic & Zhang, 2009; He & Wong, 2004). However, when discussing the impact of more complex EXC and ERC portfolios (e.g., a portfolio of high EXC and low ERC), few explanations can be found in balanced and combined effects, and thus the effect of the portfolios requires further exploration.

On the other hand, in terms of methodology, when discussing the impact of the relationship between EXC and ERC, prior research has chosen either absolute difference value (e.g., Cao et al., 2009) or multiplication (e.g., Cao et al., 2009; He & Wong, 2004; Hoang & Rothaermel, 2010) of these two capabilities. However, these methods cannot be used to discuss the EXC and ERC portfolios in different levels because they incur issues such as confounded effects and omitted information (Edwards, 2002; Shanock, Baran, Gentry, Pattison & Heggestad, 2010). In addition, to measure exploitation and exploration, the majority of these studies use survey data, which is self-reported with high levels of subjectivity (e.g. Sheng & Hartmann, 2019; Clauss, Kraus, Kallinger, Bican, Brem & Kailer, 2021). Few researchers have attempted to extract EXC and ERC from second-hand financial data.

In the present research, we attempt to investigate how different portfolios of EXC and ERC influence firms’ financial performance. Specifically, we analyze the effects of EXC and ERC on firm performance by discussing the cases of congruence and incongruence.

Using panel data of China's listed firms from 2012 to 2017 to empirically answer the research question, this research augments innovation and ambidexterity literature as follows. First, this research extends the relationship between exploitation and exploration from balanced and combined effects to congruence and incongruence cases. Specifically, we divide the EXC and ERC portfolios into different groups according to firms’ capability levels and analyze their impact on firm performance according to congruence and incongruence cases. The empirical results demonstrate that, compared with incongruence, the congruence between EXC and ERC positively influences firm performance. In the case of congruence, the higher both capabilities are, the higher the performance will be while in the case of incongruence, the portfolio of high ERC and low EXC performs better than the opposite. Second, this research introduces Response Surface Analysis (RSA) based on polynomial regression (Edwards & Parry, 1993; Edwards, 2002; Edwards & Cable, 2009) into the analysis of exploitation and exploration. RSA enables us to independently discuss different portfolios’ impacts on firm performance and compare each effect, thus providing more information. Third, this study contributes to existing research in its use of panel data from listed firms. By using stochastic frontier analysis, we extract EXC and ERC from firm's annual financial reports as a new and objective measurement method. In addition, our application of longitudinal data from listed firms enriches the research context of exploitation and exploration literature. Moreover, we aim to provide insightful managerial implications: by analyzing the (in-)congruence effect of EXC and ERC on performance, we highlight that firms must pay attention to the resource allocation between exploitation and exploration according to different cases of congruence and incongruence.

Theoretical framework and research hypothesisExploitative and explorative capabilityMarch (1991) proposes two types of innovation: exploitation activities, in which firms use existing skills and knowledge to improve efficiency, and exploration activities, in which firms develop new capabilities through new skills, knowledge and technologies. Exploitation refers to firms engaging in activities related to production, efficiency, selection, execution, and refinement, whereas exploration refers to firms engaging in activities related to search, change, experimentation and risk (March, 1991; Levinthal & March, 1993).

Following March (1991), O'Reilly and Tushman (2008) consider exploitation and exploration as dynamic capabilities. They define exploitation as a firm's capability to improve efficiency, productivity, control and reduce uncertainty, and they delineate exploration as a firm's capability to search, discover, innovate and embrace change. Yalcinkaya et al. (2007) extend this concept, defining EXC in the context of international marketing as “importer's ability to improve continuously its existing resources and processes” and ERC as “importer's ability to adopt new processes, products, and services that are unique from those used in the past”. Furthermore, Sheng and Hartmann (2019) consider EXC as the ability of a firm to refine and extend existing products and services in existing markets, whereas ERC involves radical innovation in products, services, and markets.

Based on previous research, in this study, we define EXC as a firm's ability to enhance, improve and derive value from existing products, services and markets by refining and extending current skills, processes, knowledge and resources. Therefore, to develop EXC, firms usually devote more to the advertising and promotion activities for existing products, services, and markets (Mizik & Jacobson, 2003; McAlister, Srinivasan, & Kim, 2007; Sheng & Hartmann, 2019). Specifically, two main investments are included: advertising inputs to deliver and create value for existing markets (Mizik & Jacobson, 2003; Josephson et al., 2016), and administration inputs to improve sales efficiency in existing markets (Bentley, Omer & Sharp, 2013).

ERC refers a firm's ability to develop new skills, technologies, knowledge, products and services through entering new markets, conducting experiments, and engaging in innovation. As such, firms usually develop ERC through innovation activities by investing more in R&D (Josephson et al., 2016; Piao & Zajac, 2016).

EXC and ERC vary in their goals, processes and outcomes, leading to different mechanisms when discussing their impacts on firm performance. EXC is built to meet the needs of existing markets, usually by improving existing products and services and increasing efficiency in current markets. In contrast, ERC prioritizes meeting the needs of new and potential markets, often by introducing new products and radical technology innovation (Lu Jin, Zhou & Wang, 2016). In terms of processes, enhancing EXC involves the adoption of existing technologies and capabilities to improve efficiency and is often associated with little change and risk, whereas developing ERC involves new technologies, experimentation, and radical innovations and is often accompanied by greater levels of change and risk (Atuahene-Gima & Murray, 2007; Andriopoulos & Lewis, 2009). In terms of outcomes, the results from EXC tend to be predictable in the short term (He & Wong, 2004), whereas the results from ERC tend to be unpredictable with a long-term influence (Vagnani, 2015).

Both EXC and ERC are essential for firms (Yalcinkaya et al., 2007; O'Reilly & Tushman's, 2008). However, discussions of whether EXC and ERC can coexist within firms have received much attention since the inception of the concepts of exploitation and exploration. In early studies, some scholars such as March (1991) argue that exploitation and exploration cannot coexist in firms because exploitation and exploration would compete for the firms’ scarce resources. However, with the continuous research and the practices of firms, researchers have demonstrated the successful coexistence of the two (Lisboa et al., 2011; Lu Jin et al., 2016; Wei, Ke, Liu & Wei, 2020). Therefore, based on the existing literature and firms’ practices, the present research follows the proposition that firms can maintain both EXC and ERC.

Existing research on the impact of the exploitation-exploration relationship on firm performance has not reached a uniform conclusion (see Table 1). This is primarily because the current research regarding relationship between exploitation and exploration is divided into two main categories: the balanced effects of exploitation and exploration, where firms should focus on balancing EXC and ERC (He & Wong, 2004; Cao et al., 2009), and the combined (i.e., interaction) effects of exploitation and exploration, which forefront the mutual and synergetic reinforcement of the two (Cao et al., 2009; Ho & Lu, 2015). To test these two effects empirically, prior research has utilized absolute difference value to test the balanced effect (e.g. Cao et al., 2009) and interaction value to assess the combined effect (e.g. Cao et al.; He & Wong, 2004; Hoang & Rothaermel, 2010). However, these approaches cannot clarify the specific impact of EXC and ERC on firm performance especially when specific values of the capability are not consistent (Lee, Woo & Joshi, 2017). Following Lee et al. (2017), we provide an example to further illustrate. When the portfolios of EXC and ERC are (1, 7), (7, 1), and (2, 2), in discussing the balanced effect, the absolute difference values of the (1, 7) and (7, 1) portfolios are the same: 6. However, because EXC and ERC have different mechanisms on performance, the two portfolios may produce different results even at the same level of balance. When discussing the combined effect, the multiplication of the three portfolios equals 7, 7 and 4, indicating that (1, 7) and (7, 1) may show a higher combined effect than the (2, 2) portfolio, even though the latter is balanced. Thus, the conclusions made in prior research regarding the combined effects of exploitation and exploration have not reached a consensus. For example, Ho and Lu (2015) find that the combined effect of exploitation and exploration is negatively related to firm performance, but the results from Cao et al. (2009) indicate the opposite is true. In sum, it is necessary to discuss the effect of the relationship between the EXC and ERC on firm performance based on different portfolios.

Research on effects of exploitation and exploration.

| Sources | Effects | Measurements | Data | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| He & Wong (2004) | Balanced effect; Interaction effect | Interaction:EX×ER; Balanced:|EX−ER| | Survey | Imbalance between exploitation and exploration negatively influence sales growth while interaction shows positive influence. |

| Atuahene-Gima & Murray (2007) | Interaction effect | Interaction:EX×ER | Survey | Interaction is positively related to new product performance. |

| Cao, Gedajlovic & Zhang (2009) | Balanced effect; Combinedeffect | Combined:EX×ER; Balanced:|EX−ER| | Survey | Balanced and combined effects are both positively related to firm performance. |

| Clauss, Kraus, Kallinger, Bican, Brem & Kailer (2021) | Interaction effect | Interaction:EX×ER | Survey | Interaction will negatively influence competitive advantage. |

| Ho & Lu (2015) | Interaction effect | Interaction:EX×ER | Survey | Interaction is negatively related to firm performance. |

| Luger, Raisch & Schimmer (2018) | Balanced effect; Interaction effect | Interaction:EX×ER; Balanced:|EX−ER| | Second-hand | Balance and interaction between exploitation and exploration positively improve performance. |

| Mehrabi, Coviello & Ranaweera (2019) | Balanced effect; Ccombined effect | Combined:EX×ER; Balanced:|EX−ER| | Survey | Customer management and new product development performance varies when combined and balanced effects are different. |

Note.EX represents for exploitation; ER represents for exploration.

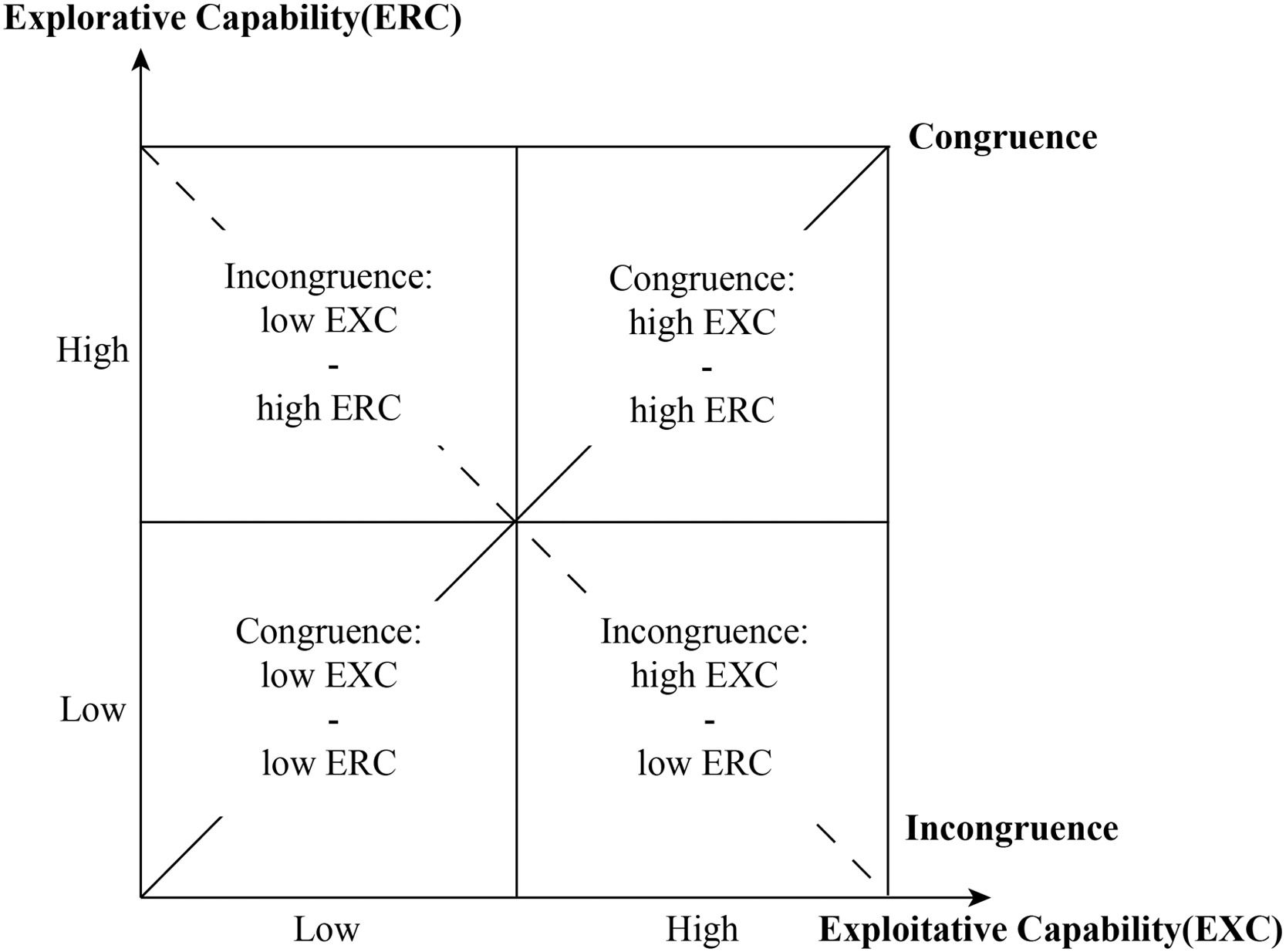

In this study, we consider two cases of firms’ EXC and ERC based on portfolios of different levels of these capabilities: congruence case and incongruence case. Like the balanced effect (He & Wong, 2004; Cao et al., 2009), the congruence case of EXC and ERC refers to those same levels of the capabilities, so there are two portfolios in the case of congruence: either high EXC- high ERC or low EXC - low ERC. In contrast, the incongruence case refers to different levels of these capabilities: either high EXC - low ERC or low EXC - high ERC.Fig. 1 depicts the portfolios of EXC and ERC under congruence and incongruence. In the following section, we discuss the congruence and incongruence cases.

Congruence versus incongruence effects on performanceAlthough EXC can bring short-term performance improvement (He & Wong, 2004), firms that demonstrate a tendency toward EXC building easily fall into "success traps" because the temporary "success" brought by EXC tricks these firms into feeling satisfied, and thus they neglect to further enhance their own core competencies and lose their sense of the changing external environments and rapid technological changes (Atuahene-Gima, 2005). In addition, firms with a tendency toward ERC easily fall into "failure traps" because ERC requires firms to invest a large amount of resources, making it difficult to achieve significant performance improvements in the short term (Atuahene-Gima, 2005). Such firms tend to get lost in massive and repeated innovation investment, thus neglecting their core competencies whilst attempting to trade present outcomes for future development opportunities (Gibson & Birkinshaw, 2004; Gupta, Smith & Shalley, 2006).

In this research, we believe that a firm's tendency toward either EXC or ERC does not lead to better performance outcomes. Similarly, March and Levinthal (1993) argue that when firms successfully balance exploitation and exploration simultaneously, they can reduce their vulnerability to the negative effects of organizational inertia and management myopia. In addition, the congruence of EXC and ERC allows firms to meet the needs of not only existing customers but also future customers (Kyriakopoulos & Moorman, 2004; Mehrabi, Coviello & Ranaweera, 2019). Furthermore, this balance of EXC and ERC allows firms to both increase efficiencies in the current product markets to gain profits and seek future growth opportunities through R&D innovation (Andriopoulos & Lewis, 2009). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1

: Compared to the incongruence case, the congruence relationship between EXC and ERC is positively related to firm performance.

EXC and ERC on performance in congruence caseIn the congruence case, the portfolios of EXC and ERC are different according to capability levels. In this research, we argue that even in the congruence case, different capability levels lead to different performance outcomes. Developing EXC is an incremental process that entails little change of existing knowledge and resources (March, 1991; Wang & Li, 2008). By building EXC, firms can maintain their competitive position and advantage in the current market. This is because, on the one hand, EXC may affect firm performance by improving and enhancing knowledge in existing markets, learning from experiences, and reinforcing existing practices to enable firms to better capture opportunities, reduce costs, and avoid losses (Crossan, Lane & White, 1999). On the other hand, because EXC emphasizes improving and optimizing current processes, firms can improve the efficiency of marketing processes including customer relationship management and supply chain management (Easterby‐Smith, Lyles & Peteraf, 2009; Lee & Rha, 2016; Mehrabi et al., 2019) to provide customers with products and services that are difficult to be imitated by competitors (Lee, Lee & Lee, 2003), which in turn strengthens their competitive advantage and brings value to firms. Therefore, firms with high EXC will perform better than those with low EXC.

ERC offers firms the possibility of exploring and discovering new business opportunities (Vorhies, Orr & Bush, 2011). With such capability, firms can leverage new knowledge and skills to explore emerging market opportunities and reduce the risks associated with new market environments (Johanson & Vahlne, 2011). In addition, ERC is important for reshaping current processes and bringing new opportunities for growth through radical innovations. The radical new products created by exploration can contribute to firms’ sustainable development (Uotila et al., 2009). The continuous investment in R&D provides a firm with a quick response in a highly competitive market (Rothaermel & Deeds, 2006; Hoang & Rothaermel, 2010). Both product and process innovation brought about by ERC can enhance firms’ flexibility, bring new market opportunities, and help firms provide more competitive products or services, which in turn enhance their competitive advantage and provide value (Lewin, Long, Carroll, 1999; Danneels, 2008; Mehrabi et al., 2019). Therefore, the higher the ERC of a firm, the better its performance will be.

In addition, EXC and ERC can play a mutually reinforcing role on the impact on performance in each case. On the one hand, EXC can facilitate the effect of ERC on performance. Huawei, a leading technology corporation, led a successful exploration in the smartphones market that benefitted from efficient channel management procedures and well-equipped product design knowledge, resulting from Huawei's continuous several-year exploitation in the telecom operator market. On the other hand, ERC can contribute to the effect of EXC on performance. Cao et al. (2009) explain this interaction effect in their study using Apple as an example: Apple's exploration of new iPhones led to incremental innovation and exploitation of older products, iPods, providing value to firm.

Thus, we can infer that in the case of congruence, portfolios with higher levels of EXC and ERC have a greater positive impact on performance than portfolios with lower EXC and ERC. Specifically, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2

: As the level of congruence between EXC and ERC increases, firm performance will increase.

EXC and ERC on performance in incongruence caseIn practice, building EXC and ERC is a dynamic process (Luger, Raisch & Schimmer, 2018), and thus the effect of required resources on EXC and ERC may vary (Gibson & Birkinshaw, 2004). Therefore, the levels of EXC and ERC are not always congruent during this process: sometimes EXC may be higher or lower than ERC, as in the incongruence case of EXC and ERC.

In this research, we argue that, in case of incongruence, a combination that has higher ERC and lower EXC leads to better firm performance than a combination that has low ERC and high EXC. On the one hand, although EXC can help firms meet consumer needs in the current markets and thus lead to short-term performance gains (He & Wong, 2004), EXC provides firms with only a temporary competitive advantage. Josephson, Johnson and Mariadoss (2016) find that, although advertising-based exploitation can bring short-term performance gains, it also greatly increases the business risk of the firm. In contrast, ERC not only can bring new market opportunities for firms through product innovations, but also truly enhance firms’ competitive advantage of firms by tapping into future growth advantages through new products and markets (Vagnani, 2015).

On the other hand, in the face of competitive markets, radical innovation activities driven by ERC can give firms a unique advantage in new market strategies, thus enabling them to grow into industry leaders (Hamel, 1998). Therefore, from the perspective of competitive advantage, ERC can bring more long-term and sustainable competitive advantage than EXC, and lead to greater benefits for the firms. Prior studies have also demonstrated that exploration based on developing new markets and substantial radically technological and product innovations can bring firms higher net present value contribution (Kim & Mauborgne, 2004; Sorescu & Spanjol, 2008). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3

: In the case of incongruence between EXC and ERC, firm performance will be higher with a portfolio of high ERC and low EXC than that of low ERC and high EXC.

MethodologyData and sampleWe selected Chinese firms listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges from 2012 to 2017 as the research sample for this study. The data for this study were obtained from the CSMAR database, an authoritative economic and financial database in China. We obtained EXC and ERC, firm's performance, and other firm-level and industry-level variables from the annual financial reports of the listed companies. We cleaned the initial data as follows: (a) excluding ST and ST* (Special Treatment) firms to ensure the reasonableness of the sample; (b) excluding the sample of firms with missing data in main variables; (c) winsorizing the data at the 1% and 99% levels to avoid influence by outliers.

After this processing, we had a total of 825 sample firms with 2061 observations as an unbalanced panel dataset for this study. Based on the 2012 industry classification by the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC), this sample is concentrated in manufacturing (73.38%), information transmission, software, and information technology services (13.58%), and wholesale and retail trade (2.96%). It is the least distributed in leasing and business services industries (0.15%).

Variables and measurementsExploitative capability (EXC) and explorative capability (ERC)We primarily measured EXC and ERC by the effectiveness of the firms’ investment of relevant resources. Quantitative studies on firms' capabilities have mainly been measured via stochastic frontier estimation (Dutta, Narasimhan & Rajiv, 1999; Kumbhakar, Lien & Hardaker, 2014; Feng, Morgan & Rego, 2017). Therefore, in this study, we also used stochastic frontier estimation to measure the firms’ exploitative capability (EXC) and explorative capability (ERC).

Stochastic frontier estimation is used to describe the effectiveness of a firm's output after inputting resources by calculating an inefficiency score, which in turn can reflect a firm's relevant capabilities. Specifically, the stochastic frontier equation is created as follows:

where Outputi,t represents a firm's resource output, Inputi,t represents resource input, εi,t is the random error term in the model, and ηi,t is the inefficiency score. Following Dutta et al. (2005) assumption that the inefficiency score should be positive in the firm capabilities scenario and the distributions based on the assumption, we can obtain the inefficiency score via Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE), and then transform the inefficiency score to obtain an efficiency score (Jondrow, Lovell, Materov & Schmidt, 1982); this value represents the firm's capability (Kumbhakar et al., 2014; Feng et al., 2017).EXC represents firms’ input-output efficiency and captures its value in existing markets by improving and upgrading the firms’ existing skills, processes and resource inputs. Previous research has demonstrated that the primary objective of EXC building is to increase sales revenue (Sarkees et al., 2014). Moreover, exploitative activities are mainly manifested in the form of advertising inputs and promotions. (Reinartz, Thomas & Kumar, 2005; Josephson et al., 2016). Therefore, based on existing studies, in the context of China's listed firms, we identified the main output of EXC to be sales revenue and the primary inputs to be sales and administrative expenses. Because the input of resources may not be observable for the current period, referring to Feng et al. (2017), we additionally included the resource input for the previous period in the model. Thus, we identified the extraction of the stochastic frontier estimation model for EXC as follows:

where, Salesi,t represents the sales revenue of the firm at time t; XSi,t and XSi,t−1 represent the sales expenses at time t and t−1; XAi,t and XAi,t−1 represent the administration expenses at time t and t−1; ηi,t represents the inefficiency score of the estimation and we converted ηi,t to obtain the variable EXC.ERC can be expressed as the efficiency of the input and output of the value obtained by a firm through innovation and experimentation. In the case of innovation, the primary output is patents, which have been used in the previous research as a measurement of firms’ competitiveness in exploration (Sarkees et al., 2014). This is because patents can represent an innovative idea that has progressed to the realization stage, thus creating value for the firm (Rothaermel & Deeds, 2006). Therefore, we used the number of patents registered by a firm to represent the main output of exploration. Regarding inputs, innovation and experimentation are primarily represented as R&D activities (Gupta et al., 2006). Josephson et al. (2016) also use the R&D inputs of firms to represent exploration. Therefore, based on existing studies, we argue that the primary resource investment in ERC is firm's R&D investment. As such, we identified a stochastic frontier estimation model for extracting ERC as follows:

where Patenti,t represents the numbers of patents the firm owns at time t; RDSi,t and RDSi,t−1 represent the R&D investments at time t and t−1; ηi,t is the inefficiency score of the estimation and ηi,t is converted to get the variable ERC.Firm performance (ROA)Drawing on existing studies, we selected firm's return on assets (ROA) as a measure of firm performance (Josephson et al., 2016; Feng et al., 2017).

ControlsIn this study, we controlled for two main categories: firm-related variables and industry-related variables. Regarding firm-related variables, we selected book value of total assets (Assets) and firm size (Size) measured by the number of firm employees. Regarding industry-related variables, we controlled for industrial competitiveness (HHI) measured by the Hirschmann-Herndahl index. We additionally controlled for market dynamics (DYN); referring to Snyder and Glueck (1982), we calculated DYN as follows:

where Salesi,t represents firm's sales revenue at time t, Salesi,t¯ represents industry's average sales revenue at time t, and NUM represents the number of firms in the industry. Also, we control the industry (Dum_ind) and year (Dum_year) dummies.Model specificationIn the present research, we used a response surface model based on polynomial regression (Edwards & Parry, 1993; Edwards, 2002; Edwards & Cable, 2009) to construct differences and additional interaction terms to avoid problems mentioned previously. This method allows us to gain a deeper and more reliable understanding of the impact of EXC and ERC on performance. Specifically, we constructed the following model:

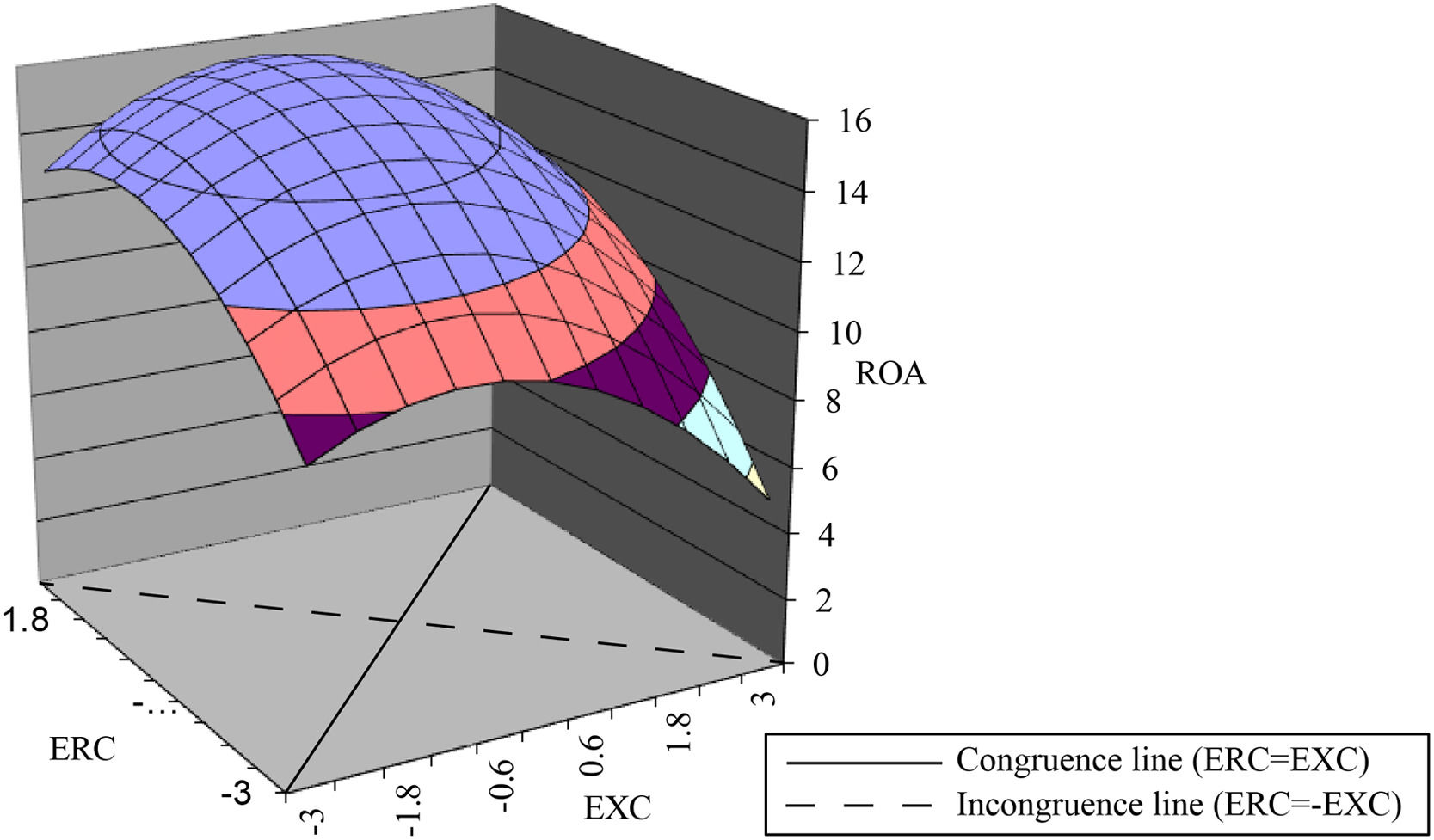

whereEXCi,t−12 and ERCi,t−12 represent the square of exploitative and explorative capability and EXCi,t−1×ERCi,t−1 is the interaction of exploitative and explorative capability. To avoid endogeneity in the model, we treated all independent variables and control variables with a one-period lag.In the RSA method, we primarily focused on the calculation of the coefficients between β1 and β5 and their significance, and based on the specific values of their coefficients, we drew a 3D surface plot (see Fig. 2), where EXC and ERC are located on both sides of the horizontal axis in the plot, and ROA is perpendicular to the horizontal axis; thus, we were able to analyze the conclusions more intuitively. In this research, according to the hypothesis, we need to analyze both congruence and incongruence and thus refine the model according to the congruence (EXC=ERC) and incongruence (EXC=-ERC) lines of the response surface.

Specifically, if the curvature (β3−β4+β5) on the incongruence line is negatively significant, the incongruence line is an inverted U-shape, indicating that the performance on the two ends of the curve is lower than in the middle of the curve (i.e., the more congruent EXC and ERC are, the higher the firm performance will be). Conversely, if the curvature is positive, firm performance will be better when the relationship between EXC and ERC is not congruent. Therefore, the curvature of the incongruence line can be used to determine whether the congruence case of EXC and ERC outperforms the incongruence case (H1). In addition, on the congruence line, the slope (β1+β2) and curvature (β3+β4+β5) indicate the impact of EXC and ERC on performance in the congruence case—namely, the combination of positively significant slope and insignificant curvature suggests that in the congruence case, higher levels of EXC and ERC indicate higher firm performance (H2). If the curvature is significant, however, further judgments will be made based on the method proposed by Edwards and Rothbard (1999). Finally, regarding the incongruence line, the lateral shift ((β2−β1)/[2×(β3−β4+β5)]) demonstrates the impact of the portfolios of EXC and ERC at different levels on performance in the incongruence case (H3). If the lateral shift is negatively significant, low EXC- high ERC portfolio indicates enhanced performance, whereas a positively significant indicates the high-EXC portfolio outperforms the opposite.

ResultsResults of empirical analysisTable 2 reports the descriptive statistics and correlations of the model used in this research. Most correlation coefficients do not exceed the critical value of 0.6 for diagnosing multicollinearity (Pelled, Eisenhardt & Xin, 1999). To further eliminate multicollinearity concern, we additionally conducted the variance inflation factor (VIF) for the explanatory and control variables, and the results demonstrate that the average VIF value of the model was 1.81 and that the VIF of each variable was significantly lesser than 10, indicating that the multicollinearity issue is unlikely to affect the analysis.

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix.

| Mean | S.D. | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) ROA | 3.78 | 4.73 | 1 | ||||||

| (2) EXC | 0.01 | 0.00 | -0.05* | 1 | |||||

| (3) ERC | 0.76 | 0.37 | 0.08⁎⁎⁎ | 0.03 | 1 | ||||

| (4) Assets | 22.37 | 1.27 | -0.02 | -0.18⁎⁎⁎ | -0.10⁎⁎⁎ | 1 | |||

| (5) Size | 7.95 | 1.22 | 0.05⁎⁎ | -0.16⁎⁎⁎ | -0.14⁎⁎⁎ | 0.83⁎⁎⁎ | 1 | ||

| (6) HHI | -0.06 | 0.11 | -0.04* | 0.00 | -0.03 | 0.15⁎⁎⁎ | 0.13⁎⁎⁎ | 1 | |

| (7) DYN | 16.41 | 2.02 | -0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.07⁎⁎⁎ | -0.09⁎⁎⁎ | 1 |

Note. N=2061, ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1. ROA represents firm's performance, EXC represents firm's exploitative capability, ERC represents firm's explorative capability, Assets represents firm's assets, Size represents firm's size, HHI represents firm's industrial competence, DYN represents market dynamism.

Table 3 presents the results of polynomial regression. Model 1 only includes control variables. Model 2 includes EXC and ERC. Model 3 is the full RSA model, which includes EXC, ERC and interaction termsEXCi,t−12, EXCi,t−1×ERCi,t−1and ERCi,t−12. According to Edwards and Parry (1993), we can use the RSA method only when at least one coefficient within EXCi,t−12, EXCi,t−1×ERCi,t−1and ERCi,t−12 is significant. The results in Model 3 reveal that, the coefficient of EXCi,t−12 is negatively significant (β=−0.32,p<0.01) and the coefficient of ERCi,t−12 is negatively significant (β=−0.27,p<0.01), indicating the RSA method is appropriate for this research.

Empirical analysis results.

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assetsi,t−1 | -0.76⁎⁎⁎ | -0.85⁎⁎⁎ | -0.75⁎⁎⁎ |

| Sizei,t−1 | 0.77⁎⁎⁎ | 0.84⁎⁎⁎ | 0.77⁎⁎⁎ |

| HHIi,t−1 | -1.59 | -1.64 | -2.15 |

| DYNi,t−1 | -0.10 | -0.09 | -0.06 |

| Exploitative and Explorative Capability | |||

| EXCi,t−1 | -0.32⁎⁎⁎ | -0.37⁎⁎⁎ | |

| ERCi,t−1 | 0.50⁎⁎⁎ | 0.90⁎⁎⁎ | |

| EXCi,t−12 | -0.32⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| EXCi,t−1×ERCi,t−1 | 0.09 | ||

| ERCi,t−12 | -0.27⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| Congruence line EXC=ERC | |||

| Slope (β1+β2) | 0.53⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| Curvature (β3+β4+β5) | -0.50⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| Incongruence line EXC=-ERC | |||

| Slope (β1−β2) | -1.27⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| Curvature (β3−β4+β5) | -0.67⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| Dum_ind | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dum_year | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 15.79⁎⁎⁎ | 16.58⁎⁎ | 15.11⁎⁎⁎ |

| F | 2.94 | 3.96 | 4.72 |

| Number of firms | 825 | 825 | 825 |

Note. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1; β1,β2,β3,β4 and β5 represent coefficients of EXCi,t−1,ERCi,t−1,EXCi,t−12,EXCi,t−1×ERCi,t−1 and ERCi,t−12.

To verify that firm performance will be higher when EXC and ERC are congruent, we calculated the curvature value on the incongruence line and tested its significance. After bootstrapping samples 5,000 times, the results reveal that the curvature is negatively significant on the incongruence line of the response surface (β3−β4+β5=−0.67, p<0.01). This in turn indicates that the incongruence line of the response surface is an inverted U-shaped curve, and the closer it is to the middle (i.e., the more congruent the two capabilities are), the better the firm performance shows. Specifically, in this study, the more congruent the EXC and ERC are, the better the performance of the firm. Therefore, H1 is supported.

To test the congruence effect of EXC and ERC, we calculated the values and tested the significance of the slope and curvature on the congruence line. After bootstrapping samples for 5,000 times, the results reveal that the coefficient of the slope of the congruence line is positively significant (β1+β2=0.53, p<0.01), which indicates that the higher the portfolio levels of EXC and ERC, the better firm performance in the case of congruence. To further show the robustness of our results, we also tested the curvature on the congruence line. However, these results showed a negative and significant coefficient of the curvature (β3+β4+β5=−0.50, p<0.01). We then followed Edwards and Rothbard (1999) and calculated the midway and standard deviation of EXC and ERC to imitate two portfolios of high EXC - high ERC and low EXC -low ERC. These results again reveal that the performance with higher capability levels was higher than the opposite; thus, H2 can be confirmed.

To test incongruence effect (i.e., whether a portfolio of high ERC and low ERC results in better performance in the incongruence case), we examined the lateral shift level of the incongruence line. After bootstrapping samples 5,000 times, the results show that the lateral shift level of the incongruence line is negative and significant ((β2−β1)/[2×(β3−β4+β5)]=−0.94, p<0.01), which indicates the left part of the incongruence line (i.e., low EXC – high ERC) demonstrates better outcome than the right side of the incongruence line (i.e., high EXC -low ERC). Therefore, in the case of incongruence, the portfolios of high ERC and low EXC outperforms the opposite. H3 is also supported.

To present the results of our response surface analysis in an intuitive way, we drew a response surface based on the results of the polynomial regression (as shown in Fig. 2). As such, we found that (a) compared with the incongruence case, firm performance is better when the EXC and ERC are congruent (thus supporting H1); (b) on the congruence line, higher levels of both capabilities indicate better firm performance (thus supporting H2); and (c) on the incongruence line, high ERC and low EXC outperforms the opposite (thus supporting H3).

Robustness checkTo avoid inconsistent findings owing to the selection of performance indicators, we further conducted a robustness check by choosing different measurements of firm's performance.

First, we selected return on investment (ROI) to replace return on assets (ROA) as a measure of firm performance. On this basis, we recalculated the base model with only control variables, the model including both EXC and ERC, and the polynomial regression model. Columns (1) - (3) in Table 4 display the results. The curvature of the incongruence line, the slope and curvature of the congruence line, and the lateral shifts support our three hypotheses, respectively, demonstrating the robustness of our conclusions.

Robustness check results.

| Variable | ROIi,t | ROAi,t+1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Assetsi,t−1 | -0.57⁎⁎⁎ | -0.65⁎⁎⁎ | -0.56⁎⁎⁎ | -0.97⁎⁎⁎ | -1.06⁎⁎⁎ | -0.93*** |

| Sizei,t−1 | 0.78⁎⁎⁎ | 0.82⁎⁎⁎ | 0.77⁎⁎⁎ | 0.88⁎⁎⁎ | 0.94⁎⁎⁎ | 0.87*** |

| HHIi,t−1 | -0.20 | -0.33 | -0.81 | -6.23 | -6.37 | -7.52* |

| DYNi,t−1 | -0.10 | -0.08 | -0.04 | -0.10 | -0.16 | -0.17 |

| Exploitative and Explorative Capability | ||||||

| EXCi,t−1 | -0.50⁎⁎⁎ | -0.55⁎⁎⁎ | -0.50⁎⁎⁎ | -0.56*** | ||

| ERCi,t−1 | 0.41⁎⁎⁎ | 0.81⁎⁎⁎ | 0.51⁎⁎⁎ | 0.94*** | ||

| EXCi,t−12 | -0.29⁎⁎⁎ | -0.35*** | ||||

| EXCi,t−1×ERCi,t−1 | 0.07 | 0.01 | ||||

| ERCi,t−12 | -0.27⁎⁎⁎ | -0.31*** | ||||

| Congruence line EXC=ERC | ||||||

| Slope (β1+β2) | 0.26⁎⁎⁎ | 0.38* | ||||

| Curvature (β3+β4+β5) | -0.50⁎⁎⁎ | -0.67*** | ||||

| Incongruence line EXC=-ERC | ||||||

| Slope (β1−β2) | -1.35⁎⁎⁎ | -1.50*** | ||||

| Curvature (β3−β4+β5) | -0.63⁎⁎⁎ | -0.66*** | ||||

| Dum_ind | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dum_year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 11.58⁎⁎⁎ | 12.94⁎⁎ | 11.55⁎⁎⁎ | 17.80⁎⁎⁎ | 19.22⁎⁎ | 17.20⁎⁎⁎ |

| F | 2.36 | 3.79 | 4.58 | 2.33 | 3.29 | 3.83 |

| Number of firms | 825 | 825 | 825 | 508 | 508 | 508 |

Note. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1; β1,β2,β3,β4 and β5 represent coefficients of EXCi,t−1,ERCi,t−1,EXCi,t−12,EXCi,t−1×ERCi,t−1 and ERCi,t−12.

Second, considering the effect of capability to perform takes time and this impact may be long term, we used ROAi,t+1 as the dependent variable, and thus the interval between the independent and dependent variables comprised two periods. Columns (4) - (6) in Table 4 show the results of the three models: again, the three hypotheses proposed in this research remain supported, indicating the robustness of our findings.

Discussion and conclusionsPrior research has discussed the balanced and combined effect of exploitation and exploration on firm performance without concluding the impact of combining the two. In the present study, we argue the impact of EXC and ERC on firm performance should be considered according to the different portfolios of these two capabilities. Therefore, we propose congruence and incongruence effects and empirically examine them by using China's listed firm data from 2012 to 2017. We find that first, compared with incongruence, congruence between EXC and ERC leads to higher performance; this finding aligns with previous research on the balancing role between exploitation and exploration (Cao et al., 2009; Raisch, Birkinshaw, Probst & Tushman, 2009). Second, congruence between EXC and ERC positively affects on firm performance; specifically, we find firms with higher levels of both capabilities perform better than firms with lower levels. This is because both EXC and ERC can contribute to firm performance, and their interaction and synergy allow them function at high levels. Third, in the case of incongruence, different portfolios have different effects on firm performance. Compared with the portfolio of high EXC and low ERC, higher ERC indicates better performance in Chinese firms. The reason is, although EXC provides short-term advantages, ERC brings long-term, sustainable competitive advantages in the pursuit of new market opportunities, technologies and products, which is especially important for Chinese listed firms facing highly fierce competition.

Theoretical implicationsFirst, previous research on the effects of exploitation and exploration on performance has largely been limited to the balanced and combined effects (Cao et al., 2009). Additionally, these studies have not reached uniform conclusions regarding these effects nor have they addressed different effects produced by portfolios in the incongruence case. In this study, the research framework on the impact of EXC and ERC on firm performance is further disaggregated according to the levels and (in-)congruence of the capabilities, thus breaking down them into more granular effects (i.e., congruence and incongruence). This allows for further investigation of the impact of EXC and ERC on firm performance. Specifically, we break the investigation into three comparison scenarios: congruent versus incongruent cases, high versus low levels of capability in the congruence case, and different levels of capability portfolios in the incongruence case. In the present framework, both the balanced and combined effects can be attributed to the congruence and incongruence cases, respectively. Therefore, this study provides various perspectives on the effects of EXC and ERC and enriches the existing findings by discussing the three scenarios mentioned above.

Second, prior studies that investigated the relationship between exploitation and exploration have used either the absolute difference value or the multiplication value. However, these approaches forfeit key information regarding the specific interpretation of this relationship, making it difficult to obtain an accurate interpretation of the variables (Edwards & Parry, 1993). In this research, however, we introduce a response surface analysis based on polynomial regression, which allows the study of the relationship between EXC and ERC to not only be limited to the balanced and combined effects, but also include complex portfolios of these capabilities in our discussion, thus providing a unique research method to ambidexterity literature.

Third, previous research has measured EXC and ERC through surveys, making it difficult to obtain large-scale panel data. In this study, our introduction of stochastic frontier estimation allows us to analyze input-output efficiency (i.e., capabilities) through financial data through determining the inputs and outputs of firms. This approach introduces a new perspective for the measurement of EXC and ERC and makes possible the testing of the hypothesis using longitudinal panel data.

Managerial implicationsFrom a managerial perspective, addressing these issues yields recommendations for firms. First, in addition to building higher levels of EXC and ERC, firms should consider to the balance of these two capabilities to achieve a stronger performance and competitive advantage. Therefore, it is not optimal for managers to focus only on advertising investment to improve EXC or R&D investment to enhance ERC. Instead, managers should prioritize a balance of resource investment and assess the weaknesses of two capabilities, thus ensure a balance of EXC and ERC to achieve higher performance.

Second, it is difficult to ensure absolute congruence between EXC and ERC. During the dynamic process of firms’ building capabilities, ERC construction should be dominant, because of its potentially long-term competitive advantage in competitive markets. Therefore, managers should consciously allocate resources for ERC building.

Limitations and future research directionsThis research is not without its limitations that may be emphasized in the future research. First, the research sample in this study solely includes on China's listed firms and does not cover other types, such as family firms, private companies, and start-ups in emerging industries. Future research could further analyze and discuss these types of firms. Second, to focus on the impact of the three different EXC and ERC scenarios on performance, we did not include moderating variables in present study. As such, future research could incorporate relevant moderating variables.

AcknowledgementsThis work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant No.72202006, 71972114] and the Young Academic Top Talent (Team) Program of Beijing International Studies University [Grant No.BJTD22A001].