The impact of history and the use of firms’ past in theoretical models examining firm strategies have garnered increasing attention. Whether firms can benefit from their history imprints to facilitate innovation strategies is an increasingly important, yet under-researched, question. This study aims to fill this gap by examining the effects of history imprint on two distinct innovation strategies: exploitation and exploration. Drawing on the history-informed perspective and imprint theory, we investigate how firm- and strategic-level factors moderate these relationships. Using a survey of manufacturing firms in China and applying hierarchical multiple regressions, we find that, while history imprint positively influences exploitation, it negatively affects exploration. Interestingly, the positive impact of history imprint on exploitation is stronger for family firms, and information sharing attenuates the negative effect on exploration. These results underscore the importance of considering history in innovative decision-making and suggest that firms, particularly family-owned ones, should adopt specific practices to balance the benefits of their history imprints with the need for innovation.

Recent research has shown a growing interest in understanding the role of history in shaping firm strategies, as it provides critical insights into strategy formulation processes and helps interpret external variations in different contexts (Argyres et al., 2020; Tosh, 2019; Vaara & Lamberg, 2016). Delving into the interplay between these two important constructs is pivotal because the strategy literature now views history as an endogenous firm resource that can be leveraged in strategic processes to improve a firm's competitive advantage (Foster et al., 2017; Hatch & Schultz, 2017; Suddaby & Foster, 2017). Integrating history and strategy, history imprint is defined as the persistence of organizational features derived from the past (Argyres et al., 2020; Johnson, 2007; Kipping & Üsdiken, 2014; Stinchcombe, 2000). From a history-informed perspective, a firm's past plays a significant role in establishing organizational culture, influencing strategic choices, and guiding future directions (Ahn, 2018; Kipping & Üsdiken, 2014). Although recent studies collectively highlight the importance of history, a significant gap remains in understanding how the past can be effectively utilized in strategic decision making. Specifically, there is limited knowledge regarding whether history imprints have a sustained and direct impact on firms’ strategic decisions, such as product innovation (Colli & Perez, 2020; Sasaki et al., 2020).

Thus, innovation strategies are crucial (Clauss et al., 2021; He & Wong, 2004; Piñeiro-Chousa et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2023). They not only help firms adapt to dynamic market conditions and changing consumer needs but also foster long-term competitiveness and sustainability (March 1991; Sousa et al., 2020). Exploitation aims to enhance the reliability of existing innovation activities through incremental advancements, whereas exploration entails the pursuit of novelty through radical experimentation (Atuahene-Gima, 2005; Vaara & Lamberg, 2016). History imprints, composed of organizational values, past successes, failures, and strategic choices, imbue firms with unique knowledge assets and cultural underpinnings that profoundly influence both current and future innovation strategies (Argyres et al., 2020; Kipping & Üsdiken, 2014; Suddaby & Foster, 2017). By drawing upon the past, firms can leverage accumulated knowledge, identify potential opportunities, and inform continuous exploratory and exploitative initiatives, which, in turn, influence the specific direction and decisions of innovation strategies (Colli & Perez, 2020; Foster et al., 2017; Ode & Ayavoo, 2020; Piñeiro-Chousa et al., 2020; Vaara & Lamberg, 2016). Therefore, understanding and effectively utilizing a firm's history is essential for formulating innovation strategies (Johnson, 2007; Stinchcombe, 2000). However, scholarly investigation of the interplay between history imprint and innovation strategy remains limited, leaving a critical research question unanswered: How does a firm's past influence its innovation strategies of exploitation and exploration (Heirati et al., 2017; Junni et al., 2013)?

To elucidate this conundrum, we draw on the history-informed perspective and the imprint theory to examine the impact of history imprints on exploitation and exploration. We further investigate whether firm- and strategic-level factors serve as boundary contingencies that moderate the relationship between history imprints and innovation strategies. The traditional perception of history views it as an immutable challenge beyond an organization's control (Colli & Perez, 2020; Suddaby et al., 2020). However, recent research contends that the impact of history imprints is not fixed but can be consciously reshaped or repositioned by leadership (Argyres et al., 2020; Sinha et al., 2020). These developments suggest that firms have the agency to manage the impacts of historical imprints. Thus, history imprints can be strategically utilized to predict innovation strategies contingent on certain boundary conditions (Colli & Perez, 2020; Tosh, 2019; Vaara & Lamberg, 2016). Accordingly, we propose that firms can capitalize on information sharing at the strategic level to harness historical imprints and promote both exploitation and exploration. Information sharing is a critical construct with significant relevance to both historical imprinting and firm innovation. It facilitates effective communication and coordination, cultivating an adaptable and collaborative organizational culture (Jap, 1999; Yan & Dooley, 2013). The exchanged information includes organizational narratives and creative concepts (Cai et al., 2010; Kulp et al., 2004). Consequently, fostering a culture of information sharing can reduce the adverse effects of historical imprints on exploratory initiatives. Additionally, ownership type at the firm level can potentially moderate the relationship between history imprints and firm innovation. The literature suggests that different types of firms experience varying levels of influence from their past, as legacy and culture play distinct roles across organizations (Breton-Miller & Miller, 2015; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011). Furthermore, firms with different ownership structures possess unique historical advantages and disadvantages that shape their innovative decision-making behavior (Ibrahim et al., 2019; Li & Zhu, 2015). Consequently, when pursuing innovation goals, firms with different ownership types are likely to experience different impacts of history imprints (Lee et al., 2003; Sasaki et al., 2020).

To address these research gaps, this study contributes to history and innovation research in three important ways. First, the traditional perspective treats history and strategy as distinct research streams, and studies exploring their relationship are limited (Colli & Perez, 2020; Vaara & Lamberg, 2016). Our research echoes Argyres et al.’s (2020) call for more studies to adopt a history-informed approach to strategy and contributes to the literature by providing empirical insights into how history imprints influence innovation strategies. Second, we extend existing knowledge on the determinants of exploitation and exploration by examining the direct impact of historical imprinting on innovation strategies. Thus, the findings offer new insights into the tension between the past and future in sustaining organizational value and culture while dealing with technological challenges (Ahn, 2018; Sasaki et al., 2020). Third, we suggest that firm- and strategy-level factors moderate the relationship between history imprints and exploitation and exploration. By focusing on firm ownership type and information sharing, this study advances the knowledge of innovation management by identifying the key conditions under which history imprints affect innovation strategies differently. It also sheds light on the intricate interplay between firm history and strategic innovation decision-making (Colli & Perez, 2020; Foster et al., 2017; Sousa et al., 2020). Our research highlights the critical importance of understanding firm history in strategic decision-making, emphasizing that history can serve as a valuable source of information and organizational identity (Argyres et al., 2020; Foster et al., 2017; Hatch & Schultz, 2017; Suddaby & Foster, 2017). Additionally, it underscores the need for strategic-level information sharing to balance the bias toward exploitation, while recognizing the distinct characteristics of family and non-family firms in leveraging their history of innovation and competitive advantage (Cai et al., 2010; Kulp et al., 2004).

Theory and hypotheses developmentResearch background and theoretical foundation: history-informed strategy and imprint theoryTraditionally regarded as distant areas of research, history and strategy have recently attracted academic attention for exploring their intersection (Foster et al., 2017; Suddaby & Foster, 2017; Vaara & Lamberg, 2016). This increasing interest has generated a rich body of work, suggesting that history plays an important role in strategy formulation and has been employed in areas such as path dependence research (Kieser, 1994; Kluppel et al., 2018), strategy and organizational structure (Chandler, 1977; Whittington & Mayer, 2000), the resource-based view (Barney, 1991; Kor & Mahoney, 2004), and geographic clusters (Buenstorf & Klepper, 2009). Specifically, history-informed strategy research is defined as “strategy research that draws on historical research methods and/or leverages history as a key component (or variable) of theory or empirical analysis” (Argyres et al., 2020, p.345). Historical research methods refer to research techniques that compile, describe, and critically analyze primary and secondary historical data to explain and interpret phenomena (Argyres et al., 2020; Kipping & Üsdiken, 2014).

History has mainly informed strategy research by incorporating the past into theoretical models, using history as a central variable to enrich theoretical explanations of strategy (Kipping & Üsdiken, 2014). Rather than viewing history as an exogenous variable beyond managerial control, this perspective treats history as an endogenous resource that can be managed for strategy building (Suddaby & Foster, 2017; Suddaby et al., 2020). History is not merely viewed as data or a methodological approach for examining such data. Instead, history is recognized as a vital element in theoretical construction (Argyres et al., 2020). The ability to manage a firm's history has become essential, as knowledge and resources from the past set future directions and create sustained competitive advantages (Sasaki et al., 2020; Suddaby & Foster, 2017; Suddaby et al., 2020). For example, De Massis et al. (2016) suggest that firms’ underlying capabilities to internalize and reinterpret past knowledge can help build long-lasting competence, making these firms more innovative. Suddaby et al. (2020) prove that interpreting the past is critical for managers to sense, seize, and reconfigure business opportunities.

Embedded in the history-informed strategy perspective, imprint theory focuses on imprinting at the firm level, such as the impact of the organizational environments in which organizations were founded and the influence of critical decisions made in the early stages (Johnson, 2007; Marquis & Tilcsik, 2013; McEvily et al., 2012). It leverages the power of the past and suggests that an organization's history creates an imprint that leaves a long-lasting impact on business practices (Kipping & Üsdiken, 2014; Tilcsik, 2012). The notion of imprinting was first introduced in organizational research by Stinchcombe (1965), who demonstrated that organizations are influenced by the conditions existing at the time of their founding (Marquis & Tilcsik, 2013). Imprint theory has since been applied in various settings, including network analysis, institutional theory, and organizational ecology, emphasizing the roles of tradition, heritage, and legacy (Johnson, 2007; Marquis & Tilcsik, 2013; McEvily et al., 2012; Tilcsik, 2012). For example, Ahn (2018) presents a study of Korean companies, finding that founder tenure and a strong founder legacy positively impact a company's long-term survival. Jaskiewicz et al. (2016) show that an entrepreneurial legacy motivates entrepreneurship in the current generation. Similarly, Erdogan et al. (2020) proved that the long-lasting legacy of previous generations significantly influences the strategies developed by the current generation.

History imprint, a significant variable in imprint theory, refers to the imprint derived from an organization's past in the organizational environments in which it was founded and developed (Johnson, 2007; Marquis & Tilcsik, 2013; Simsek et al., 2015; Stinchcombe, 2000). This is based on the premise that the conditions surrounding an organization during its founding and initial development will have a long-lasting impact throughout its entire lifespan (Stinchcombe, 2000). First, firms experience many salient moments and events, such as organizational birth, changes in industries or main products and core technologies, becoming a public company, mergers or acquisitions, changes in ownership or organizational structure, and replacing members of the senior management team. These events certainly leave a mark and exert important influence on business development and organizational decision-making (Kipping & Üsdiken, 2014; Marquis & Tilcsik, 2013). Second, history imprints also include imprints of internal institutional conditions, such as organizational culture, traditions, routines, and values (Baron & Newman, 1990; Johnson, 2007). These factors strongly influence firms’ strategic choices (Marquis & Huang, 2010). The historical imprinting process is a transitional period, with its impact reflected in decision-making and enduring in organizational culture and values, even amidst future changes in internal or external environments (Marquis & Tilcsik, 2013).

Despite the recent surge of interest in the concept of history imprint, our understanding of how such imprints shape firms’ innovation strategies remains limited (Argyres et al., 2020; Kipping & Üsdiken, 2014). There is a paucity of knowledge regarding how firms can effectively deal with history imprints. Thus, this study aims to contribute to the existing history and strategy literature by examining the impact of history imprint on exploitation and exploration, while also testing whether firm ownership type and information sharing moderate these relationships. The conceptual model is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Hypotheses development: history imprint and innovation strategiesDeveloped by March (1991), organizational learning theory suggests that exploration and exploitation are two types of innovation strategies. Exploitation is defined as refining and extending existing knowledge in the current product-market domain, including activities characterized by refinement, efficiency, and improvement. It refers to discovery-related actions aimed at entering new product-market domains, such as firm activities involving search and experimentation (Gupta et al., 2006; Heirati et al., 2017; March 1991; Raisch et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2023; Wu & Shanley, 2009; Zhang et al., 2017). Exploitation and exploration are associated with two different types of organizational learning processes and represent distinct innovation strategies aimed at different sets of goals (Clauss et al., 2021; Gupta et al., 2006; He & Wong, 2004; Lavie et al., 2010). Exploitation relies on experiential learning that capitalizes on the strengths of existing products or services and is often characterized by efficiency, routinization, and a tight culture (He & Wong, 2004; Koryak et al., 2018). On the other hand, exploration emphasizes experimental learning and radical adaptation, typically aligning with flexibility, autonomy, and a loose culture (He & Wong, 2004; Koryak et al., 2018; Lubatkin et al., 2006; Wu & Shanley, 2009).

We theorize that a firm's history imprint positively affects its innovation strategy of exploitation. A firm experiences many salient moments in its life cycle that leave important imprints on its future development and growth (Marquis & Tilcsik, 2013; Simsek et al., 2015; Stinchcombe, 2000). Innovation and technological breakthroughs are viewed as some of the most significant moments in a firm's historical evolution (Marquis & Tilcsik, 2013; Piñeiro-Chousa et al., 2020). As a firm evolves over time and the level of history imprint increases, more historical marks influence business practices and strategic choices, which magnifies internal complexities (Jawahar & McLaughlin, 2001). Such internal complexities and challenges necessitate unique investments in resources and technologies to continuously navigate firms’ business directions and ensure their survival (Josephson et al., 2016). In other words, as history imprints increase, firms endure more imprints, leading their strategic emphasis to shift in response to idiosyncratic needs for survival (Miller & Friesen, 1984; Tushman & O'Reilly, 1996). These firms focus on maintaining strong and stable sales growth, expanding into new markets, and gaining economies of scale through exploitation (Agarwal & Gort, 2002). Furthermore, when firms have a higher level of history imprint, they typically have more traditions and routines associated with daily business practices and strategy development, fostering a tight culture (He & Wong, 2004; Koryak et al., 2018; Lubatkin et al., 2006). The literature has provided strong evidence that routinization and tight culture promote incremental innovation, with a high history imprint, strong emphasis on work rules and routines, and low flexibility facilitating experiential learning and exploitative innovation (Jansen et al., 2006; Lavie et al., 2010; Mishina et al., 2004). Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H1: History imprint is positively associated with exploitation.

We also posit that history imprint has a negative effect on exploration innovation strategy. History imprints focus on the power of the past and the conditions surrounding a firm during its founding and development processes (Johnson, 2007; Marquis & Tilcsik, 2013; Simsek et al., 2015; Stinchcombe, 2000). When the level of history imprint increases, excessive rules and procedures derived from the past and routinization may emerge, which in turn constrain deviations from established norms and practices (Berard & Frechet, 2020; Jung et al., 2008). Therefore, a high level of history imprint can restrict the potential to generate new knowledge and novel innovations (Baron & Newman, 1990; Johnson, 2007). In line with this reasoning, the imprint of history may serve as a frame of reference that hinders exploration, as routinization often becomes deeply ingrained over time to maintain predictable business practices rather than venturing into uncertain and risky paths (Jansen et al., 2006; Jaskiewicz et al., 2016).

Furthermore, a high level of history imprint, along with established routines, practices, and structures, can create boundaries and potential organizational inertia (Baron & Newman, 1990; Jansen et al., 2006; Jaskiewicz et al., 2016; Lavie et al., 2010; Miller & Friesen, 1984). Past research suggests that organizational inertia impedes radical innovation and that high inertia hinders risk-taking, experimental learning, and exploratory innovation (Jansen et al., 2006; Lavie et al., 2010; Mishina et al., 2004). Organizational inertia reduces employees’ autonomy, hampers innovative thoughts, and discourages their willingness to take the risks inherent in developing an innovation strategy focused on exploration (Jaskiewicz et al., 2016; Raisch et al., 2009; Rondi et al., 2018). Thus, a high history imprint may make it difficult to change the technological course and limit the chances of creating new opportunities and innovations (Shi & Zhang, 2018). In contrast, firms with a low level of history imprint are less burdened by the past, tend to be more creative, and exhibit a stronger entrepreneurial spirit (Marquis & Huang, 2010; Tushman & O'Reilly, 1996). In addition, firms with fewer historical marks are more likely to have the flexibility and autonomy to develop radical technological breakthroughs and promote a strong focus on exploration (Agarwal & Gort, 2002; He & Wong, 2004; Josephson et al., 2016; Koryak et al., 2018; Lubatkin et al., 2006). Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H2: History imprint is negatively associated with exploration.

Previous literature indicates that a multitude of factors shape firms’ innovation strategies, with internal influences playing a particularly significant role (He & Wong, 2004; March 1991; Sousa et al., 2020). Therefore, we expect history imprints to affect exploitation and exploration differently, depending on firm- and strategic-level factors. At the firm level, we focus on firm ownership type as an important contingency factor. Family firms are those owned and managed by family members (Li & Zhu, 2015; Sharma & Salvato, 2013). We posit that the positive relationship between history imprints and exploitation is stronger for family firms. Family firms are typically under long-lasting influence from their founding families and are particularly susceptible to past impacts (Ibrahim et al., 2019; Li & Zhu, 2015). This is because of the persistence of the founder's legacy, facilitated by substantial family ownership and involvement (Lee et al., 2003; Sasaki et al., 2020). Moreover, family firms are tied to bonds of shared values and tend to promote these values across individuals and departments (Breton-Miller & Miller, 2015; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011). The literature on family firms suggests that the business norms and values established by founding families constitute pivotal elements of these firms and serve as important factors leading to their success (Lee et al., 2003; Sasaki et al., 2020).

A significant shared value among generations in family firms is a risk-averse approach and a steadfast focus on firm survival (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011; Li & Zhu, 2015). Therefore, as history imprints increase, family firms bear more imprints, strengthening their strategic emphasis on survival. This is reflected in shifts in innovation strategy toward exploitation (Miller & Friesen, 1984; Tushman & O'Reilly, 1996). Family firms are often perceived as conservative, which in turn fosters a more pronounced positive relationship between history imprint and exploitation, highlighting a focus on refining existing technologies and products (Ibrahim et al., 2019; Li & Zhu, 2015). Accordingly, we hypothesize the following:

H3: The positive effect of history imprint on exploitation is stronger for family firms.

At the strategic level, we focus on information sharing as an important corporate mechanism and propose that it moderates the relationship between history imprint and exploration in that it attenuates the negative effect of history imprint on exploration. Information sharing refers to the continuous exchange of pertinent and valuable information among members of a firm (Cai et al., 2010; Yan & Dooley, 2013). The goal of information sharing is to enhance communication and coordination, ultimately fostering a more flexible and cooperative organizational environment (Jap, 1999; Yan & Dooley, 2013). The types of information exchanged may include organizational stories and innovative ideas (Cai et al., 2010; Kulp et al., 2004). Thus, information sharing can reduce the extent to which history imprints negatively affect exploration.

First, information sharing helps foster a flexible organizational environment (Kemp et al., 2021). Due to routinization, firms with a high level of history imprint are more likely to face a lack of flexibility and autonomy in taking risks for radical innovation (Agarwal & Gort, 2002; He & Wong, 2004; Josephson et al., 2016; Koryak et al., 2018; Lubatkin et al., 2006). By sharing information across organizations, individuals and teams can stay informed about organizational histories, and more importantly, the rationales behind organizational norms and routines (Jap, 1999; Yan & Dooley, 2013). Therefore, such information sharing can empower employees and managers to gain a comprehensive understanding of organizational routines. Consequently, they can adapt these practices to meet the strategic needs of innovation and embrace experimental innovation shifts rather than adhering to them rigidly and unconditionally (Joshi, 2009; Josephson et al., 2016).

Second, information sharing includes the sharing of creative ideas, and therefore, promotes the generation of new knowledge (Cai et al., 2010; Kulp et al., 2004; Ode & Ayavoo, 2020). Thus, information sharing can mitigate the negative impact of organizational inertia associated with high levels of history imprints. Organizational inertia stifles innovative thinking and discourages firms from developing exploratory innovation strategies (Raisch et al., 2009; Rondi et al., 2018). However, when employing information sharing, firms need to actively gather valuable market data, interpret it across different departments, and generate intelligence to effectively digest the information (He & Wong, 2004; March 1991; Zhang et al., 2017). The process of information sharing thus ensures that information flows freely among different levels and units of a firm, reduces learning and knowledge inertia, and allows for more open communication of innovative thoughts, which enhances exploration (Jap, 1999; Yan & Dooley, 2013). Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H4: Information sharing attenuates the negative impact of history imprint on exploration.

MethodDataTo test these hypotheses, we collected data from China. This study focuses on high-technology industries, including telecommunications, electronics, and information technology. This context is appropriate for examining the relationships among the focal constructs. First, history plays an important role in business development and growth in China (Joseph & Wilson, 2018; Warner, 2013). In an era of rapid change, the rhetorical perception of organizational decision-making is increasing there (Li & Wu, 2010; Liu, 2020). Second, as a large emerging economy and a key player in world trade, China has invested in both exploitation and exploration innovation strategies (Peng et al., 2018). Third, the sampled industries are well-established with national coverage in China, and the multi-industry setting offers greater variance in the focal constructs.

We first developed an English-language questionnaire and had it translated into Chinese by a professional translator. We ensured conceptual equivalence through back translation using a different translator. Researchers and translators worked together to resolve conflicts and confusing terms (Hoskisson et al., 2000). To improve the content and face validity, we conducted a pilot study with 15 senior managers to ensure an accurate understanding of the measures. Based on the pilot study results and respondent feedback, we further refined the survey instruments (MacKenzie et al., 2011).

We collaborated with a data research agency to obtain a comprehensive list of high-technology manufacturing firms in China. Focusing on the electronics, information technology, and telecommunication industries, we generated a list of over 20,000 firms. We then selected a random sample of 500 firms from diverse regions using a stratified random selection procedure. This involved dividing the list into 20 groups based on sales revenue and randomly selecting 25 firms from each group to create the sample (Ott & Longnecker, 2010). The random selection of 500 firms allowed us to increase the sample size while adhering to the research budget constraints. For each firm, we contacted a senior manager (e.g., general manager, vice president, or senior manager) to gather information regarding the external market environment. Senior managers were selected based on their comprehensive understanding of strategic decisions and market dynamics. To reduce common method bias, we also collected data from middle-level managers (e.g., marketing, sales, R&D, and other department managers) regarding firm innovation. Middle-level managers were chosen for their operational insights and hands-on experience with innovation processes. Additionally, we obtained archival data on firm-level variables such as size and assets. Appendix A presents the sample's demographics.

To improve the quality of the survey results, professional interviewers were hired to conduct on-site visits to collect the data (Hoskisson et al., 2000). We successfully obtained 171 usable responses (342 informants), resulting in a response rate of 34.2 % (171 out of 500). The results show that our respondents were highly familiar with their firms’ histories and innovation strategies, with an average knowledge rating of 6.58 out of 7. To assess non-response bias, we compared the demographics of the responding and non-responding firms in terms of firm size, assets, sales model, and sales region. We detected no statistical differences, suggesting that non-response bias was not a major concern in this study (Armstrong & Overton, 1977).

MeasurementWe adapted measures from established studies and assessed all perceptual items using a seven-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree,” 7 = “strongly agree”). Appendix B lists the measurement items and validity assessments for each construct. Following Atuahene-Gima (2005), we use a four-item scale to measure exploitation and a five-item scale to measure exploration. We measured exploitation by emphasizing firms’ intent to utilize activities such as efficiency, refinement, selection, and implementation. Exploration assessed a firm's exploratory activities, including search, discovery, variation, and experimentation. Following Ahn (2018), Boeker (1989), and Lian et al. (2015), history imprint was captured by firm age and the number of years of operation since the founding date. Firm age indicates the level of integration between business stories and development. Therefore, older firms tend to have higher levels of imprint (Kipping & Üsdiken, 2014; Koiranen, 2002; Marquis & Tilcsik, 2013). Martinez et al. (2019) and Boeker (1989) suggest that the length of time a business has existed indicates the influence of salient organizational moments, which can be used as a proxy measure of history imprint. We assessed information sharing using three items adapted from Cai et al. (2010) regarding the extent to which firms proactively exchange and share information throughout the organization. Ownership type was measured as a dummy variable, where the baseline was non-family firms, and 1 represented family firms.

We included five control variables in the model: firm size, firm asset, industry type, market uncertainty, and technological turbulence. Firm size and assets have considerable explanatory power regarding firm performance (Arya & Zhang, 2009; Giachetti et al., 2019). We measured firm size as the logarithm of the total number of employees. Firm assets were assessed using the logarithm of total assets (Lee & Chu, 2013; Mishra & Ewing, 2020). Industry type, market uncertainty, and technological turbulence represent operational challenges in terms of adaptation, which lead to diverse innovation decisions (Peng & Heath, 1996). We measured industry type as a dummy variable, where the baseline denoted the electronics industry, and 1 denoted information technology and telecommunication. We used a three-item scale of changes in customer preferences, adapted from Theodosiou and Katsikea (2013), to measure market uncertainty. Following Theodosiou and Katsikea (2013) and Shu et al. (2017), we employed a four-item scale to measure technological turbulence by assessing the speed of change in technology in high-technology industries. Table 1 presents the correlation matrix and descriptive statistics. Including both firm- and industry-level control variables was crucial for accurately assessing the relationships in our study. This comprehensive approach enhances the robustness and generalizability of our findings, ensuring that they are not confounded solely by internal or external influences (Aldrich & Auster, 1986; Porter, 1980).

Descriptive statistics and correlations.

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Exploitation | 4.42 | 0.94 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 2. Exploration | 3.82 | 0.99 | 0.06 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 3. History Imprint | 11.22 | 8.85 | 0.36⁎⁎ | −0.18* | 1.00 | |||||||

| 4. Information Sharing | 4.60 | 0.63 | 0.20⁎⁎ | 0.11 | 0.07 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 5. Ownership Type | 0.33 | 0.47 | −0.07 | 0.18* | −0.20* | 0.02 | 1.00 | |||||

| 6. Firm Size | 2.38 | 0.54 | 0.21⁎⁎ | −0.09 | 0.21⁎⁎ | −0.01 | −0.12 | 1.00 | ||||

| 7. Firm Asset | 3.90 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.23⁎⁎ | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.21⁎⁎ | 1.00 | |||

| 8. Industry Type | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.10 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.08 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.10 | 1.00 | ||

| 9. Market Uncertainty | 4.12 | 1.19 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.17* | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.09 | −0.14 | 1.00 | |

| 10. Technological Turbulence | 5.08 | 1.09 | −0.05 | 0.26⁎⁎ | −0.01 | 0.08 | 0.09 | −0.05 | 0.10 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 1.00 |

Note: ⁎⁎⁎p < 0.001.

We assessed the reliability and validity of the constructs in several steps. First, face validity was established through a pilot study. Second, using exploratory factor analysis, we ensured that all items were loaded onto their designated variables without cross- or low-factor loadings. Third, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis, and the results showed a satisfactory fit (χ2 = 234.4, d.f. = 134, p < 0.001; confirmatory fit index (CFI) = 0.95; Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = 0.94; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.06). The factor loadings were statistically significant for every indicator of the respective construct (p < 0.001), supporting convergent validity. We calculated χ2/d.f., which was 1.75 (Schermelleh-Engel et al., 2003). The composite reliabilities ranged from 0.78 to 0.94, indicating adequate reliability (Lance et al., 2006). Fourth, we conducted nested model comparisons between the unconstrained and constrained models for all possible construct pairs. The chi-square differences ranged from 7.12 to 25.35 (p < 0.001), supporting discriminant validity (O'Leary-Kelly & Vokurka, 1998).

Although we collected data from multiple sources, the potential problem of common method bias cannot be completely eliminated. Therefore, we first adopted Harman's single-factor test to assess this issue (Podsakoff & Organ, 1986; Podsakoff et al., 2003). We conducted a factor analysis with all constructs, and the results showed a solution for five factors. These five factors accounted for 78.9 % of the variance, whereas the first factor accounted for 26.6 %. We then used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to model all construct items as indicators of a single factor (Mossholder et al., 1998). The results indicated an unsatisfactory model fit. Finally, we employed a method variance (MV) marker to test for potential bias (Lindell & Whitney, 2001). We chose a four-item scale to measure firms’ integrated marketing communications. The correlation between the MV marker and the other variables in the model ranged from 0.014 to 0.16 (Verhoef & Leeflang, 2009). We then adjusted for construct correlations and statistical significance using the second-lowest correlation between the MV marker and technological turbulence (r = 0.02) (Lindell & Whitney, 2001; Malhotra et al., 2006). None of the significant correlations became non-significant after adjustment. Taken together, common method bias is not a serious concern.

Analysis and resultsWe ran hierarchical multiple regressions to test our model, including the interaction effects (Aiken & West, 1991). Hierarchical multiple regression allows for the examination of the unique contributions of each predictor variable while controlling for others, making it particularly suitable for understanding the relationships among history imprint, exploitation, and exploration (Aiken & West, 1991; Cohen et al., 2003). Additionally, this method effectively elucidates the moderating effects, enabling us to assess how factors such as ownership type and information sharing influence the primary relationships under investigation (Cohen et al., 2003). We addressed the potential threat of multicollinearity by calculating variance inflation factors (VIFs). The results show that all VIF values ranged from 1.02 to 1.22, which are well within the acceptable range given the sample size and variances of the estimates. Therefore, multicollinearity was not a major concern (O'Brien, 2007). The estimated effects of historical imprints on exploitation and exploration are presented in Table 2. Models 1–3 use exploitation as the dependent variable, while Models 4–6 examine exploration as the dependent variable. Models 1 and 4 include all control variables, whereas Models 2 and 5 include historical imprints, ownership type, and information sharing. Models 3 and 6 further incorporate the interaction effects. For the control variables, our analysis shows that firm size has a positive and significant effect on exploitation (β = 0.16, p < 0.05), indicating that larger firms are more likely to engage in exploitative activities. However, the effect of firm size on exploration was not significant. Additionally, we found that technological turbulence positively influences exploration (β = 0.21, p < 0.01), suggesting that firms operating in dynamic environments are more inclined to explore new opportunities, while it does not significantly affect exploitation.

Results of Hierarchical Multiple Regressions.

| Independent Variables | Exploitation | Exploration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Firm Size | 0.21⁎⁎(2.70) | 0.18*(2.34) | 0.16*(2.21) | −0.13(−1.69) | −0.09(−1.12) | −0.09(−1.21) |

| Firm Asset | −0.05(−0.63) | −0.13(−1.72) | −0.14(−1.83) | 0.13(1.64) | 0.14(1.82) | 0.17*(2.11) |

| Industry Type | 0.12(1.60) | 0.09(1.29) | 0.09(1.23) | −0.02(−0.30) | −0.02(−0.33) | −0.05(−0.68) |

| Market Uncertainty | 0.13(1.74) | 0.09(1.27) | 0.05(0.70) | 0.14(1.87) | 0.13(1.68) | 0.10(1.29) |

| Technological Turbulence | −0.03(−0.40) | −0.04(−0.55) | 0.01(0.07) | 0.25⁎⁎⁎(3.37) | 0.24⁎⁎(3.22) | 0.21⁎⁎(2.88) |

| Information Sharing (IS) | — | 0.17*(2.37) | 0.14*(2.00) | — | 0.07(0.97) | 0.10(1.34) |

| Ownership Type (OT) | — | 0.02(0.30) | 0.24⁎⁎(2.60) | — | 0.09(1.25) | 0.08(1.05) |

| Main Effect | ||||||

| History Imprint (HI) | — | 0.34⁎⁎⁎(4.56) | 0.73⁎⁎⁎(5.69) | — | −0.18*(−2.40) | −0.24⁎⁎(−3.03) |

| Interaction Effects | ||||||

| HI × OT | — | — | 0.48⁎⁎⁎(3.68) | — | — | — |

| HI × IS | — | — | — | — | — | 0.18* (2.28) |

| R2 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.19 |

| F Value | 2.63 | 5.41 | 6.68 | 4.23 | 3.95 | 4.18 |

| Number of observations | 171 | 171 | 171 | 171 | 171 | 171 |

Note: t-value in parentheses.

H1 predicts that history imprint positively leads to exploitation, which is supported by the results from Model 3 (β = 0.73, p < 0.001). H2 states that history imprint has a negative effect on exploration, which is supported by the results of Model 6 (β = −0.24, p < 0.01). H3 states that firm ownership type strengthens the positive impact of history imprint on exploitation, and Model 3 supports this hypothesis, showing that the interaction between history imprint and family firms is positively significant (β = 0.48, p < 0.001). H4 suggests that information sharing positively moderates the effects of history imprint on exploration, and this is supported by the results from Model 6 (β = 0.18, p < 0.05).

We also conducted analysis to validate our findings. We utilize patent data to operationalize exploitation and exploration, with exploitation measured by the number of patents related to existing products and exploration indicated by the number of new patents in novel areas (Katila & Ahuja, 2002; March 1991). We then tested alternative model specifications using this operationalization to confirm the robustness of the relationships under different conditions. Our results remained highly consistent. This robust analysis strengthens the conclusions drawn from our findings.

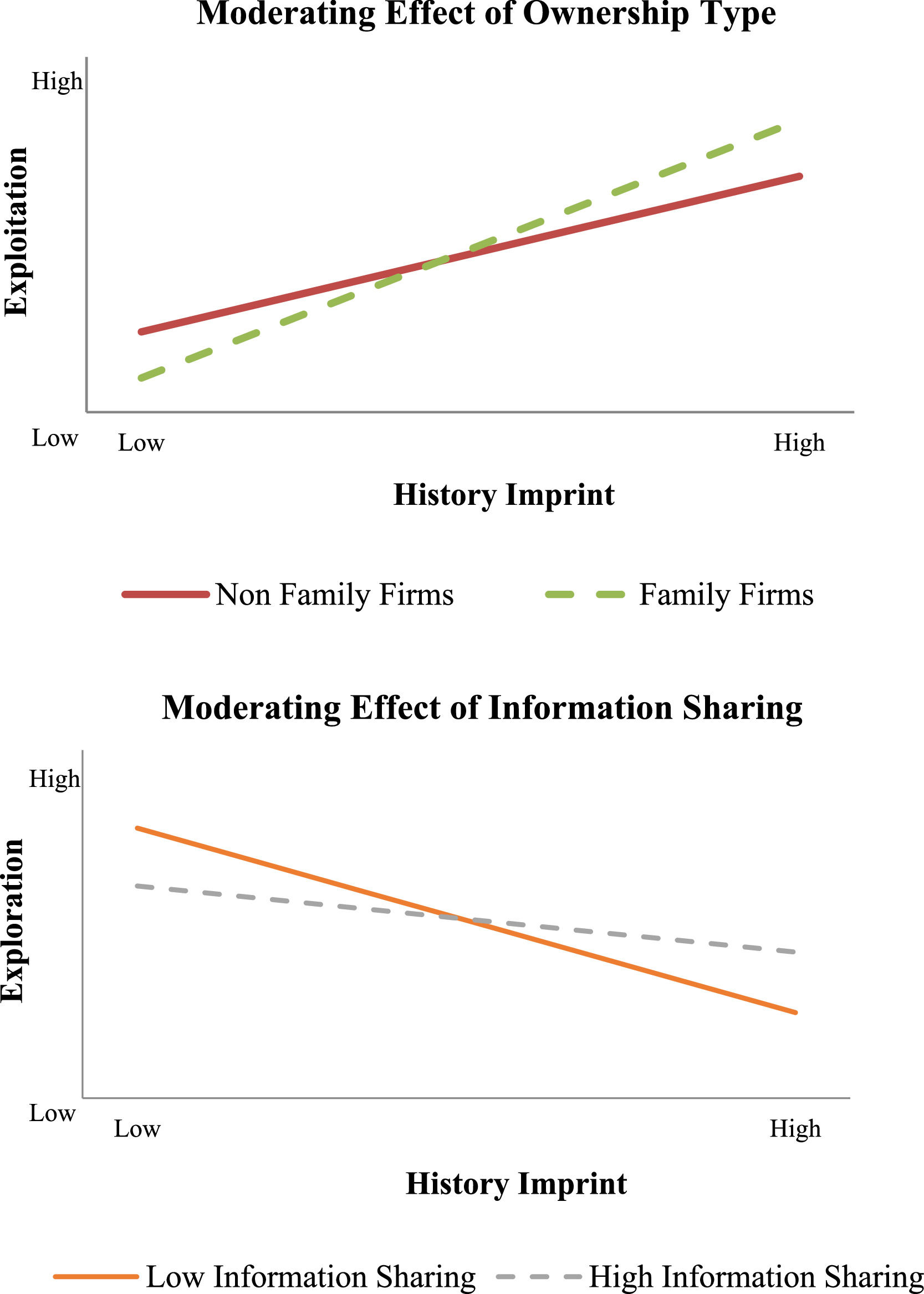

The two-way interaction effects are shown in Fig. 2. We demonstrate the effect of history imprint on exploitation for family and non-family firms (Aiken & West, 1991). Fig. 2 suggests that the positive impact of history imprint on exploitation is stronger for family firms, with a steeper slope. Similarly, we split the information-sharing variable into two groups (a high group with two standard deviations above the mean and a low group with two standard deviations below the mean). We estimated the effects of history imprint on exploration at both levels. Fig. 2 indicates that the negative relationship between history imprint and exploration is attenuated at high levels of information-sharing, with a shallower slope.

DiscussionThis study explores the important interplay between history imprint and innovation strategies (Johnson, 2007; Marquis & Tilcsik, 2013; Simsek et al., 2015; Stinchcombe, 2000). From a history-informed perspective, we investigate the direct impact of history imprint on both exploitation and exploration (Argyres et al., 2020; Kipping & Üsdiken, 2014; Vaara & Lamberg, 2016). Our findings reveal a nuanced relationship: history imprint positively affects exploitation, while it negatively impacts exploration. Additionally, this study contributes to underexplored areas by examining critical moderating factors at both the firm and strategic levels. Specifically, firm-level ownership type moderates the positive relationship between history imprint and exploitation, while strategic-level information sharing attenuates the negative relationship between history imprint and exploration. Our empirical results support the proposed research model.

Theoretical implicationsThis study contributes to the development of this theory in several ways. First, it contributes to general innovation strategy research by extending the growing literature on history (Argyres et al., 2020; Colli & Perez, 2020; Tosh, 2019; Vaara & Lamberg, 2016). As noted by Kipping and Üsdiken (2014) and Sasaki et al. (2020), research fields of history and strategy have traditionally remained separate. In recent years, scholars have shown increasing interest in exploring the intersection of these two disciplines (Suddaby & Foster, 2017; Suddaby et al., 2020). In response to the call for more research in this area, our study deepens our systematic understanding by investigating the role of history in strategy-making (Argyres et al., 2020; Sasaki et al., 2020). The expanding literature mainly focuses on historical analysis using longitudinal datasets; however, there has been limited empirical testing of how organizations utilize history as an endogenous resource and variable for strategy development (Argyres et al., 2020). This is due to the methodological and empirical challenges associated with history-informed strategy research (Kipping & Üskiden, 2014; Suddaby et al., 2020). This study makes a meaningful contribution to organizational learning theory by constructing an integrated conceptual model that captures the interplay between history and innovation, supported by empirical validation.

Second, this study advances history-informed strategy research by contributing to ongoing conversations about the role of the past in shaping innovation strategies. De Massis et al. (2016) and Erdogan et al. (2020) suggest that a firm's past is an important resource for innovation, endowing it with reservoirs of knowledge, foundational value, and cultural elements that significantly shape innovative strategies. Thus, we take a step forward by separately addressing the direct impacts of history imprint on exploitation and exploration. Building upon prior research affirming that the past is powerful in predicting firms’ innovative activities (e.g., Rondi et al., 2018; Shi & Zhang, 2018), our study enriches the literature by demonstrating that while history imprint tends to impede exploration efforts, it stimulates exploitation endeavors. As the magnitude of the history imprint intensifies, it can engender an abundance of rules and procedures originating from past experiences, making it difficult to change the technological course and limiting the opportunities for new innovations (Berard & Frechet, 2020; Jung et al., 2008; Shi & Zhang, 2018). Conversely, as history imprint increases, firms’ strategic emphasis shifts to reflect their idiosyncratic survival needs, leading to more incremental innovative activities (Jansen et al., 2006; Lavie et al., 2010; Mishina et al., 2004). Thus, our study provides detailed insights into the strategic utilization of the past in the development of innovation strategies.

Third, this study enhances the strategy literature by further emphasizing a contingency perspective in examining the interplay between history imprint and innovation strategies. Given that history imprints are inherently inclined toward exploitation rather than exploration, our investigation focuses on how firm- and strategic-level factors moderate the relationship between history imprint and innovation strategies, potentially alleviating this inherent bias. While previous studies have largely overlooked the contextual conditions associated with the influence of firm history, our research addresses this gap by proposing that ownership type and information sharing are critical contingent factors shaping the impact of a firm's history imprint on innovation (Argyres et al., 2020; De Massis et al., 2016; Erdogan et al., 2020). Specifically, the positive effect of history imprint on exploitative innovation is amplified in family firms, whereas information sharing reduces the negative influence of history imprint on exploratory innovation. Thus, our study highlights the importance of adopting a contingency view and expands both the conceptual and empirical boundaries to understand how historical imprints are utilized in the development of innovation strategies.

Managerial implicationsOur study has several important implications for managerial practices. First, we emphasize the importance of understanding the impact of firm history on strategic decision-making. Managers need to recognize that firm history is not merely a relic of the past; rather, it can serve as a rich source of information, the foundation of organizational identity and culture, and a roadmap for navigating change and adaptation in response to evolving market dynamics and competitive pressures (Buenstorf & Klepper, 2009; Kluppel et al., 2018; Kor & Mahoney, 2004; Whittington & Mayer, 2000). By understanding a firm's history and history imprinting, managers can make informed decisions regarding future directions and competitive positioning (Argyres et al., 2020; Foster et al., 2017; Hatch & Schultz, 2017; Suddaby & Foster, 2017). Moreover, it is important to recognize that history imprints may lead to a bias toward exploitation rather than exploration. This suggests the importance of balancing exploitation and exploration (Clauss et al., 2021; He & Wong, 2004). While leveraging historical imprints for exploitation can lead to short-term gains, neglecting exploration may hinder long-term adaptability and competitiveness (Atuahene-Gima, 2005; Gupta et al., 2006; Junni et al., 2013).

Second, to address this bias, firms should emphasize the critical role of strategic-level information sharing in shaping the relationship between history imprint and innovation strategies. Managers should prioritize strategic information-sharing mechanisms to foster exploration activities (Cai et al., 2010; Kulp et al., 2004). By facilitating the exchange of knowledge, insights, and experiences across different departments, managers can create an environment conducive to exploration (Jap, 1999; Yan & Dooley, 2013). Additionally, acknowledging the moderating effect of firm ownership type on the relationship between history imprint and exploitation, managers must recognize that family and non-family firms have distinct organizational characteristics and priorities that influence their approaches to exploitation (Breton-Miller & Miller, 2015; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011). For family firms, managers should emphasize the value of their historical imprints in driving exploitation strategies. Non-family firms may not possess the same traits as family firms, but they can benefit from studying the strategies and practices of family firms that successfully leverage historical imprints for exploitation. This may include understanding how family firms uphold their heritage and foster shared values across generations (Ibrahim et al., 2019; Li & Zhu, 2015).

Limitation and future researchOur study has several limitations that warrant consideration and present opportunities for future research. First, conducting history-informed strategy research entails addressing methodological and empirical challenges in capturing the interplay between history and strategy (Argyres et al., 2020; Kipping & Üskiden, 2014; Suddaby et al., 2020). This involves obtaining datasets that can track how firms make decisions over time to achieve organizational outcomes or why they fail to attain these outcomes (Argyres et al., 2020; Vaara & Lamberg, 2016). We acknowledge that our measurement of history using firm-age imprint has some limitations. Although this measurement is reasonable and has been used in prior research (e.g., Ahn, 2018; Martinez et al., 2019), future research should employ a more refined measurement to reexamine the observed phenomena. For instance, tapping into longitudinal sources of historical imprints could help validate the findings, as it would facilitate the examination of how a firm's past manifests and evolves over time, providing a deeper understanding of its impact on innovation strategies. Moreover, firms usually shift their focus to innovation strategies, and how history imprints enable such shifts may evolve over time (Josephson et al., 2016). A longitudinal framework can also assist in exploring this intersection and its evolution (McKendrick & Carrol, 2001). Second, we test our hypotheses using survey data from China. Thus, relying on data from a single country may limit the generalizability of the findings. Collecting data from other contexts would be beneficial to further corroborate our conclusions. For example, cultural norms and values vary across contexts, which can affect the driving forces of innovation strategies (Junni et al., 2013; Sousa et al., 2020). Third, researchers can explore other contingency factors at various levels — strategic, firm, and industry — to better understand the nuances of the relationships between history imprints and innovation strategies. Market dynamism, competitive intensity, and technological turbulence can influence how a firm's past shapes its innovation activities (Shu et al., 2017). Therefore, future research should further investigate the various organizational capabilities and traits that can effectively leverage firm history to facilitate exploitation and exploration (Argyres et al., 2020; Piñeiro-Chousa et al., 2020; Vaara & Lamberg, 2016).

ConclusionIn summary, this study provides a comprehensive examination of the interplay between history imprinting and innovation strategies, revealing that history imprint positively influences exploitation while negatively affecting exploration. By identifying critical moderating factors such as ownership type and strategic-level information sharing, this study offers valuable insights into how firms can leverage their history imprints to enhance innovation strategies. The theoretical contributions of this study extend the existing literature on innovation strategy by integrating a history-informed perspective and highlighting the importance of considering the historical context in strategic decision-making (Argyres et al., 2020; Colli & Perez, 2020; Tosh, 2019; Vaara & Lamberg, 2016). Additionally, the findings emphasize the need for a balanced approach to exploitation and exploration, suggesting that firms should adopt contingency strategies to mitigate the inherent biases associated with history imprints (Clauss et al., 2021; He & Wong, 2004; Raisch et al., 2009). From a managerial perspective, understanding the impact of a firm's history is crucial for informed strategic decision-making. Managers should recognize the dual role of history imprints in fostering exploitation while potentially hindering exploration. Firms can better navigate the complexities of innovation strategy development by promoting strategic-level information sharing and considering the unique characteristics of different ownership types. Overall, this study underscores the significance of history imprints in shaping innovation strategies and provides a foundation for future research to further explore this intricate relationship.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMin Ju: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Gerald Yong Gao: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

| Demographic Variables | Description | # Firms | % |

| Firm Location (Regions) | East China | 54 | 46.15 |

| South China | 30 | 25.64 | |

| North China | 25 | 21.37 | |

| West China | 8 | 6.84 | |

| Firm Size | Small (1–50 employees) | 40 | 34.19 |

| Medium (51–250 employees) | 50 | 42.73 | |

| Large (251+ employees) | 27 | 23.08 | |

| Industry | Electronics | 65 | 55.56 |

| Information technology | 25 | 21.37 | |

| Telecommunications | 27 | 23.07 | |

| Respondent Years of Experience | <5 years | 80 | 34.19 |

| 5–10 years | 90 | 38.46 | |

| >10 years | 64 | 27.35 | |

| Respondent Title | General manager | 40 | 34.19 |

| Vice president | 37 | 31.62 | |

| Senior manager | 40 | 34.19 | |

| Marketing department manager | 25 | 21.37 | |

| Sales department manager | 30 | 25.64 | |

| R&D department manager | 40 | 34.19 | |

| other managers | 22 | 18.80 |

| Constructs (7-point scale, 1= “very low”; 7= “very high”) | Loading c |

|---|---|

| Exploitation CR a = 0.78 AVE b = 0.53 | |

| Over the last three years, to what extent has your firm:Invested in exploiting mature technologies that improve the productivity of current innovation operations.Enhanced abilities in searching for solutions to customer problems that are near to existing solutions.Upgraded skills in product development processes in which the firm already possesses rich experience.Strengthened the knowledge and skills to improve the efficiency of existing innovation activities. | 0.920.680.661.00 |

| Exploration CR = 0.94 AVE = 0.75 | |

| Over the last three years, to what extent has your firm:Acquired manufacturing technologies and skills entirely new to the firm.Learned product development skills and processes entirely new to the industry.Acquired entirely new managerial and organizational skills that are important for innovation.Learned totally new skills in funding new technology and training R&D personnel.Strengthened innovation skills in areas where it has no prior experience. | 0.810.980.941.000.93 |

| Information Sharing CR = 0.88 AVE = 0.71 | |

| We have processes for sharing information effectively throughout the organization.We have processes for sharing information between all parties involved in the decisions.We have processes for transferring organizational knowledge to individuals (such as employee training programs). | 0.551.000.84 |

| Market Uncertainty CR = 0.83 AVE = 0.63 | |

| In our industry, customers tend to look for new products all the time.Customers’ product preferences change frequently over time.Market demand is difficult to forecast in our industry. | 0.841.000.61 |

| Technological Turbulence CR =0.87 AVE =0.63 | |

| The technology in our industry is changing rapidly.Technological changes provide substantial opportunities in our industry.A large number of new product ideas have been made possible through technological breakthroughs in changes in our industry.It is very difficult to forecast where the technology in this area will be in the next few years | 0.911.000.700.87 |

| Overall Model Fit: χ2(134) = 234.4, p < 0.00; TLI= 0.94, CFI = 0.95, RMSEA= 0.06. | |

Note: a Composite reliabilityb Average variance extracted c Standardized fixed factor loading, all significant at level of p < 0.001.