Two questions persist regarding global value chains (GVCs): First, what are the strategies and pathways through which multinational enterprises (MNEs) integrate and navigate GVCs? Second, what are the characteristics of GVCs in which MNEs participate? An analysis of these questions leads to inside–out and outside–in perspectives on GVCs. The literature on MNEs mostly focuses on the quantity and quality of foreign direct investment rather than on the differences in MNEs’ production activities and structure of GVCs. This study examines the effects of MNEs’ participation in simple and complex GVCs on domestic innovation. We find that the positive effects are mainly driven by MNEs’ downstream participation in simple GVCs. The mechanism tests indicate that MNEs’ upstreamness within simple GVCs negatively affects domestic firms’ absorption capacity and internal R&D and that within simple and complex GVCs negatively affects domestic firms’ export resilience.

To understand the nature of global value chains (GVCs), it is crucial to regard firms, rather than countries or industries, as the primary participants (Antràs, 2020). According to Cigna et al. (2022), multinational enterprises (MNEs) play a dominant role in global production and GVC-related trade, representing over one-third of the total output, 65% of exports, and 41% of intermediate input imports. MNEs facilitate the integration of developing economies into global networks of fragmented production and collaborative innovation (Lee & Gereffi, 2021; Mody, 2004; Pietrobelli & Rabellotti, 2011), embedding local business ecosystems and global divisions of labor (Saranga et al., 2019; van Meeteren & Kleibert, 2022).

Although MNEs represent the largest source of technological innovation and transfer (Iammarino & McCann, 2013), the Porter paradox asserts that enduring competitive advantages in a globalized era originate from local things (Porter, 1998), impelling the analysis of the economic consequences of MNEs’ GVC-related activities on host countries’ innovation performance. However, previous research on how MNEs affect domestic innovation focuses mainly on the quantity and quality of foreign direct investment (FDI), for example, the foreign equity shares in the horizontal, upstream, and downstream sectors (Vujanović et al., 2022) or foreign firms’ patent applications and patent grants (Tan et al., 2023). When the quantity and quality of FDI reflect a country's attractiveness to FDI, they cannot accurately describe the differences in the technological intensity and market strategies embodied in specific production activities. Thus, the research focus must shift to the fundamental nature of MNEs’ production activities that cater to the local markets of host countries and serve as the critical elements of the global production sequence. Specifically, MNEs not only sell the same products in the same way worldwide (Levitt, 1983) but also contain a considerable portion of the production networks spanning multiple countries (Pandya, 2016). Moreover, from a structural perspective on MNEs’ global production, the extant literature centers on the GVC governance theory with a focus on micro-interfirm coordination (Bair, 2008) while ignoring the broader network structure of GVCs (Ambos et al., 2021). As GVC complexity is a basic network structural feature that reflects the specialization patterns of countries and industries (Wang et al., 2017), we analyze the participation of MNEs in simple and complex GVCs and their impact on domestic innovation. Two questions draw our attention: What strategies and pathways do MNEs use to integrate and navigate GVCs? What are the characteristics of the GVCs that engage MNEs? Thus, the analysis of these two issues effectuates the inside–out and outside–in perspectives in GVCs.

Based on the above analysis, we fill this research gap by investigating the specific impact of MNEs’ participation in simple and complex GVCs on domestic firms’ innovation performance. Additionally, we analyze how domestic firms’ heterogeneity affects the impact of MNEs’ participation in GVCs on domestic firms’ innovation performance, including factors such as domestic firms’ R&D intensity and revealed comparative advantage (RCA). Finally, we analyze the theoretical mechanisms, including domestic firms’ internal R&D, absorption capacity, and export resilience.

This study contributes to existing literature in several ways. First, it provides an alternative perspective for investigating inside–out (firm-to-network) and outside–in (network-to-firm) GVCs. McWilliam et al. (2020) and Pananond et al. (2020) highlight this combination of complementary perspectives. They integrate GVC governance theory with the ownership, location, and internalization advantage (OLI) paradigm and MNEs’ global strategy. We interpret how MNEs undertake production activities in specific GVC structures and how these structures affect the internal organization and external relationships of MNEs, which represent inside–out and outside–in perspectives, respectively. Specifically, this study empirically analyzes the complexity of intercountry industrial connections and MNEs’ GVC participation. Second, it contributes to the literature on FDI. The existing literature focuses on how MNEs enter host countries through FDI and underestimates the GVC production activities organized and dominated by MNEs in host economies (Harding & Javorcik, 2012; Crescenzi et al., 2015; Lin & Kwan, 2016; Lu et al., 2017; Amendolagine et al., 2019). This study clarifies the mechanisms through which FDI generates positive spillovers to developing countries through GVC participation. Finally, it contributes to literature on firm innovation and industrial upgrades. As the interactive and open nature of innovation is widely recognized (Ambos et al., 2021; Buciuni & Pisano, 2021), how innovation progresses along the specific paths of GVC participation and structures of GVCs must be further explored.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows. Section 2 provides the theoretical background and introduces the research hypotheses. Section 3 presents the empirical methodology, and Section 4 reports the empirical results of the baseline regression, robustness, and heterogeneity tests, and mechanism identification. Section 5 presents the discussion. Finally, section 6 presents the conclusions and limitations of this study.

Theoretical background and hypothesis developmentThe relationship between GVC participation and domestic innovation is widely recognized. From an internal perspective, extant literature mainly analyzes the participation and positions of domestic firms within GVCs (Elshaarawy & Ezzat, 2023), which affect the capability of value creation and access to high-quality intermediates. From an external perspective, technology spillovers are examined through bilateral international trade (Coe & Helpman, 1995) and indirect spillovers to other firms, industries, and countries that trade with direct partners (Ito et al., 2023). From the latter perspective, as MNEs exploit and absorb new ideas and technologies across national borders, their participation in GVCs generates network externalities for local innovations. According to Antràs (2020), a GVC refers to a series of stages engaged in the production of a product or service destined for final consumption, with each production stage adding value and at least two different countries are involved in production. This transcends the GVC governance structure and local production activities in which MNEs collaborate with domestic firms. In this context, a comprehensive mindset is critical for analyzing the interactive nature of fragmented global production. Connecting the firm-to-network (inside–out) perspective with the network-to-firm (outside–in) perspective is the core of the GVC–OLI nexus (McWilliam et al., 2020). Furthermore, we can consider the participation of MNEs and overall structure of GVCs, which represent inside–out and outside–in perspectives, respectively. The traditional OLI paradigm is widely applied to analyze the extent, pattern, and geographic dispersion of MNEs’ foreign value-adding activities (McWilliam et al., 2020). Moreover, GVC-related specialized production reflects the value-adding process, indicating an important aspect that relates to the basic questions of the OLI paradigm. GVC complexity emanates from the value-adding activities of MNEs in GVCs, reflecting the entire technological process, which is segmented and distributed across several countries. Therefore, foreign MNEs’ production activities in simple and complex GVCs reveal the direction, extent, and mechanisms of their impact on the innovation performance of domestic firms.

As the GVC–OLI nexus must address the basic questions of the OLI paradigm from the perspective of the GVC structure, this study examines it by focusing on the internalization decisions of MNEs in simple and complex GVCs. When the structure and processes of MNEs become increasingly complex (Andrews et al., 2023), the “I” sub-paradigm of OLI is a potent analytical tool to understand the organization of internalized activities and control of externalized relationships in complex production networks (Rugman & Verbeke, 2003; Zeng et al., 2023). Literature on the internalization theory highlights the trend of MNEs shifting from vertical integration to network orchestration. This shift enables MNEs to capture the location- and ownership-specific advantages of domestic firms without direct equity controls (Scott-Kennel & Enderwick, 2004; Asmussen et al., 2022). As efficiency is an axiom of the internalization theory, MNEs optimize governance modes and exploit position advantages to manage other economic actors and maximize self-interest (Benito et al., 2019). To address the challenges associated with GVC complexity, MNEs apply organizational mechanisms to control and coordinate cross-border production activities, including centralization, standardization, socialization, and output-oriented mechanisms (Zeng et al., 2023). Therefore, GVC complexity causes variations in the internalization decisions of MNEs for greater efficiency because transaction costs, information codifiability, and the distribution of risks and benefits are distinct, indicating that the overall structural attributes of GVCs are intricately intertwined with the internalization theory.

As a complex network phenomenon, GVC is analyzed from a social network perspective. Assortativity and homophily are essential for analyzing the formation and evolution of GVC production networks. According to Pan et al. (2022), the former involves selective linking and assortative mixing. MNEs with high connectivity prioritize local firms with abundant connections. The latter pertains to a phenomenon in which individual units form connections with others possessing similar characteristics or a tendency for differences between them to diminish over time after building connections. This may effectuate reinforced connections within similar groups of MNEs and domestic firms and diminish the transfer of information and resources between different groups through segregation patterns (Currarini et al., 2009; Jackson et al., 2017). Specifically, the potential positive spillovers from MNEs’ participation in complex GVCs to domestic firms are limited and subject to several constraints. For example, complex GVCs are organized by MNEs with similar technological advantages, impeding cooperation between MNEs and domestic firms in host countries.

Previous research has concentrated on the knowledge and technology spillovers from MNEs indicated by the OLI framework to investigate the specific mechanisms by which MNEs influence domestic firms (Ascani & Gagliardi, 2020; Paul & Feliciano-Cestero, 2021; Xiao & Tian, 2023). Fundamentally, MNEs collect fragmented advantages by externalizing certain production activities. First, the efficacy of spillovers for domestic firms is contingent on their absorption capacity (Duan et al., 2021; Jha et al., 2024; Moralles & Moreno, 2020), which is influenced by external factors and is path dependent. Second, internal R&D inputs are critical for promoting innovation performance and are the most important means for accumulating unique advantages. Owing to the demonstration and competition effects (Lu et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2023), internal R&D inputs of domestic firms can be augmented or substituted by the presence of MNEs. Finally, as GVC governance relationships are unstable (Ponte et al., 2019), it is important to determine whether MNEs affect the resilience of domestic firms. MNEs may exhibit varying degrees of opportunism across diverse production contexts and affect domestic firms’ export resilience to risk and disruption by integrating them into globalized operations. In addition, existing literature proves that the overall network perspective is crucial for understanding individual strategies and diffusion of knowledge and risk (Jackson et al., 2017). Therefore, this study investigates how MNEs’ participation in GVCs affects domestic firms’ innovation performance through internal R&D, absorption capacity, and export resilience, against the backdrop of GVC complexity.

Viewing GVCs inside–out and outside–in: Effects of MNEs’ participation in simple and complex GVCsFollowing the above analysis, we construct an argument regarding the association between MNEs’ participation in GVCs and domestic firms’ innovation performance. MNEs reinforce the depth and complexity of the host economies’ integration into GVCs through their inherent links to production networks. GVC participation paths indicate different levels of strategic coupling. In diverse industrial and commercial contexts, MNEs coordinate global production, effecting asset complementarity between them and domestic firms. The upstream and downstream production stages exhibit distinct value-creation capabilities. From an inside–out perspective, MNEs’ direct participation in upstream production activities indicates control of downstream participants. As downstream participants, they rely on intermediate inputs from upstream GVC participants. The more upstream MNEs participate in GVCs, the more imitation and competition they create among domestic enterprises. In contrast, domestic firms have more opportunities to accumulate complementary assets and cooperate with MNEs that focus on downstream GVC production.

As GVC complexity is a critical factor affecting the dissemination of risks, new ideas, products, and the impact of MNEs engaging in GVCs varies between simple and complex GVCs. Unlike risk, which is unavoidable and can be intentionally transferred, knowledge transfer is restricted and expensive. From an outside–in perspective, when complex GVCs represent highly specialized divisions of labor, MNEs exploit low-cost advantages in host countries such as labor, land, and natural resources but do not source directly from local firms. This kind of fragmented production, which is different from local production and sales, facilitates economies of scale for specific production stages in host economies and provides optimal production arrangements for MNEs at a global level. Given the high technological intensity inherent in complex GVCs, MNEs’ participation in international specialization poses challenges for domestic firms in emerging economies. This is because of strict selection criteria, which favor only domestic firms possessing advanced technologies. Thus, emerging economies have comparative advantages in simple GVCs, providing opportunities for collaboration between MNEs and domestic enterprises. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H1a The greater the upstream participation of MNEs in GVCs, the more negative the effect on domestic firms’ innovation performance. Therefore, the positive impact of MNEs’ participation in GVCs is generated through downstream participation.

H1b The positive impact of the downstream participation of MNEs in GVCs mainly occurs in simple GVCs.

MNEs progressively shift their global strategic paradigm from vertical integration to interorganizational relationships and networks to maintain core assets, capabilities, and knowledge. Additionally, interfirm knowledge transfer and collaboration synergies have emerged (Andersson & Forsgren, 2000; Reilly & Sharkey Scott, 2014; Meyer et al., 2020). The extent to which external spillovers benefit domestic firms depends on their absorptive capacity. Generally, the adverse impact of FDI on emerging economies arises from inadequate conditions to support absorption. However, external factors associated with MNEs also influence their absorptive capacity.

The evolution of absorptive capacity is dependent on historical trajectories and paths, entailing a trade-off between inward-looking vis-à-vis outward-looking absorptive capability; an excessive dominance by either of them can render an enterprise's innovation system dysfunctional (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Lewin et al., 2011; Crescenzi & Gagliardi, 2018). In a firm, internal R&D generates new knowledge and boosts the absorptive process (Hejazi et al., 2023), indicating the complementary and substitutive dynamics between internal R&D and external spillovers. As internal and external factors present appropriate harmony, domestic firms can prevent innovative capabilities from being eroded by external factors such as reliance on MNEs’ technology transfer. Some scholars analyze the asymmetric properties of spillover effects, revealing the importance of spillover directionality (Knott et al., 2009). We posit that asymmetry is related to MNEs’ positions within GVCs, which determine the power–dependence relationship and affect the creation and appropriation of value in the entire production network. As GVC orchestrators, MNEs create architectural advantages to appropriately high levels of value without resorting to vertical integration (Jacobides et al., 2006) and utilize this power to access resources that are beneficial for maintaining competitive advantage. Given the ambiguity that whether MNEs generate positive spillovers (Alfaro, 2017; Rojec & Knell, 2018), how MNEs participate in GVCs explicates this ambiguity. We anticipate that the upstream GVC activities of MNEs are mainly oriented toward market-seeking motivations, effecting less co-specialization than the downstream GVC activities. Specifically, the main directionality of spillovers in GVC production sharing is backward, similar to previous research (Javorcik, 2004), which excludes the GVC context.

From an internal perspective, R&D is a catalyst promoting a firm's quantity and quality of innovation. Focusing on the R&D–production relationship, scholars uncover conflicting findings on the effects of coupling and decoupling R&D and production (Buciuni & Finotto, 2016; Buciuni & Pisano, 2021). The tendency to separate global R&D and production activities varies according to their capabilities to manage complex and geographically dispersed organizational structures (Castellani & Lavoratori, 2020). Considering the fragmented nature of GVCs, the separation of R&D and production takes precedence because the focus is on accessing innovative concepts rather than possessing them (Ambos et al., 2021). Specifically, MNEs’ participation in upstream GVCs may substitute domestic firms’ innovation, whereas downstream participation incurs MNEs’ input demands for local suppliers. Although upstream GVC production activities make R&D a private good, sufficient conditions for facilitating technology and knowledge transfers are lacking. Moreover, domestic firms’ dependence on high-quality inputs from MNEs, ceteris paribus, diminishes the marginal returns on independent R&D. Similar to absorption capacity, how MNEs affect domestic firms’ R&D in complex GVCs is ambiguous, and domestic firms can engage in basic R&D in simple value chains. Domestic firms engage in complementary R&D activities to provide external technological opportunities. Therefore, marginal returns on domestic firms’ R&D increase if MNEs participate in downstream production activities in simple GVCs. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H2a The upstream participation of MNEs in GVCs negatively affects the absorption capacity and internal R&D of domestic firms, negatively affecting domestic firms’ innovation performance.

H2b The negative effects of MNEs’ participation in GVCs on internal R&D and absorption capacity of domestic firms occur primarily in simple GVCs.

Efficiency and resilience are interconnected as they represent complementary facets for safeguarding firms’ competitive advantages and capabilities to resist risks and disruptions. Under tremendous uncertainty and instability (Martin et al., 2018), robust resilience helps firms resist and quickly adjust to risks and disruptions. The trade–investment nexus of GVCs is restructuring, effecting shifts in the geographical distribution of production stages and patterns of strategic coordination among different actors (Gereffi, 2014). The strategic focus of MNEs on network orchestration may indicate an increasing cost of transactions for MNEs and other firms because of their decreasing control and increasing ex ante uncertainty. Especially, the contract incompleteness contributes to the sticky attribute of GVCs and makes participants in GVCs vulnerable to risk and disruption (Antràs, 2020) because of the difficulty to establish credit. Acemoglu et al. (2007) examine the correlation between contractual incompleteness, technological complementarity, and technology adoption. They suggest that heightened contractual incompleteness causes the adoption of less advanced technologies and that this influence intensifies in cases where intermediate inputs exhibit higher levels of complementarity.

Upstream and downstream participation in GVCs generates heterogeneous effects on domestic firms’ export resilience, as they represent market- and resource-seeking activities, respectively, engendering varying degrees of interdependence and technological complementarity. With greater participation in upstream GVC segments, MNEs create more added value and protect their core technologies through segregation mechanisms. In addition, compared with downstream GVC participation, upstream GVC participation signals less asset complementarity and greater power for strategic maneuvering. Considering that the nature of the risk mentioned in the previous section differs from that of knowledge and technology, the effect of MNEs’ participation in simple and complex GVCs on domestic firms’ export resilience is significant. In simple GVCs, once the comparative advantage of firms in emerging countries surpasses that of domestic firms, MNEs can relocate their production operations. In complex GVCs, the increasing cost of coordination is associated with increased contract incompleteness, which negatively affects domestic firms’ export resilience. Hence, we hypothesize the following:

H3a The upstream participation of MNEs in GVCs negatively affects domestic firms’ export resilience, negatively affecting domestic firms’ innovation performance.

H3b The negative effect of MNEs’ participation in GVCs on domestic firms’ export resilience occurs in both simple and complex GVCs.

Fig. 1 presents our conceptual model.

MethodologySample and dataThis study focuses on China, the largest developing nation, that has emerged as a new regional center within GVCs (Gao et al., 2021) and plays a crucial role in complex GVCs. Significant inward foreign direct investment (IFDI) facilitates China's industrialization process, integrating it into global production networks and international markets (Lu et al., 2017). As the principal beneficiary of IFDI, the manufacturing sector serves as a vital link between China and the global economy.

Our sample comprises 15 manufacturing industries for 2005–2015. We select this period because of the availability of key data and advantages of industry-level aggregate data. The data for measuring innovation performance and testing mechanisms are obtained from the Statistics Yearbook on Science and Technology Activities of Industrial Enterprises, which selects the category of domestic firms that we prioritize during 2005–2015. The rationale behind employing industry-level aggregate data on enterprises arises from their expansive statistical coverage, which encompasses both large-scale enterprises and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The data indicate that SMEs constitute 70% of China's technological innovation (Zhang et al., 2023). One limitation of this dataset is that the industry-level aggregate data may lose some information about individual firms.

Traditional intercountry input–output (ICIO) tables provide a relatively complete picture of GVC-related production activities compared with firm-level data without reflecting the characteristics of heterogeneous firms (Fortanier et al., 2020). However, firm-level studies only reflect the backward linkages of GVCs, that is, the purchases of intermediate and final goods from abroad. Therefore, it is impossible to further differentiate between firms’ purchases of foreign products for domestic use and exports, resulting in the ratio of foreign value added to exports being greater than 1. ICIO tables distinguishing domestic and foreign firms at the industry level bridge the gap between micro- and meso-data.

ICIO tables distinguishing domestic and foreign firms are sourced from the OECD AMNE database. We consolidated C29 and C30 of the analytical activity of multinational enterprises (AMNE) database to address the inconsistencies in industry classification standards between the different databases. Table A in Appendix presents an industrial correspondence table and industry classification criteria. Data for the control variables were obtained from China's National Bureau of Statistics and China Industry Statistical Yearbook. Given that China's National Bureau of Statistics and China Industry Statistical Yearbook do not provide a separate classification for domestic enterprises, we exclude foreign-invested and Hong Kong-, Macao-, and Taiwan-invested industrial enterprises.

Variables and measuresThe dependent variable is the innovation performance of domestic firms (Inn). We focus on new product development performance, which directly reflects and sustains a firm's innovation performance (Subramanian & Vrande, 2019). This is calculated using the natural logarithm of new product sales per unit of new product development expenditure. In our robustness tests, we use the ratio of invention patent applications to total patent applications as a measure of innovation performance.

Our independent variable is the production position of MNEs within GVCs (FGVC_PS), which measures and interprets the path of participation in GVCs. The higher the index, the more upstream the MNEs are in GVCs. Conversely, the lower the index, the more downstream the MNEs are in GVCs. Consistent with Koopman et al. (2010), we refer to value-added exports based on forward linkages as upstream participation, and intermediate goods imports based on backward linkages as downstream participation, which reflect the production stage at which the participant is located. The GVC measurements are primarily based on trade or production decomposition. The latter includes GDP decomposition and final goods decomposition using forward and backward linkages, respectively, which further measure the production length and relative upstream position of GVCs. Regarding deeper comprehension of the growing intricacy and refinement of production networks, novel metrics that can capture the “length” of the connections are necessary (Meng et al., 2020). According to previous research (Wang et al., 2022, 2021, 2017), the positions of MNEs within GVCs based on production length are calculated by disaggregating the distribution of value addition across the entire GVC as follows:

andFGVC_PS is the ratio of PLv_FGVC to PLy_FGVC, and PLv_FGVC is the average forward production length from the MNEs’ production of intermediate goods to final production in other countries. V_FGVC represents the value added generated by MNEs through intermediary exports; Xv_FGVC is the aggregate output resulting from MNEs’ value added through the exports of intermediate goods; PLy_FGVC is the average backward production length from foreign countries’ production of intermediate goods to the final production of MNEs in the host country; Y_FGVC is the foreign value added embodied in MNEs’ imports of intermediate goods; Xy_FGVC denotes the output of final goods generated by MNEs within the country, effectuating from the imports of foreign intermediate goods.

Simple and complex GVCs exhibit different complexity levels. In simple GVCs, domestic or foreign value added crosses national borders only once. In complex GVCs, value added crosses national borders more than twice. Therefore, the construct of GVC complexity depends on the number of times the intermediate inputs cross national borders. The more the times, the more specialized the global division of labor. The dichotomy between simple and complex GVCs is based on the following equation:

andV_FGVC_S is the domestic value added embodied in MNEs’ intermediate exports used by the directly importing country to produce products consumed in domestic markets. V_FGVC_C is the domestic value added embodied in MNEs’ intermediate exports, which are used by the directly importing country to produce intermediate or final products. Y_FGVC_S is the foreign value added that MNEs import directly from partner countries to produce products for domestic consumption by host countries. Y_FGVC_C is the returned domestic value added or foreign value added embodied in intermediate imports used by MNEs in host countries to produce final products for domestic consumption or exports.

Therefore, the positions of the MNEs within the simple and complex GVCs (FGVC_PS_S and FGVC_PS_C) is calculated as follows:

andThe variables used to test the theoretical mechanisms are domestic firms’ absorptive capacity, internal R&D, and export resilience. We use the absorption cost, which is the ratio of technology absorption expenditure to technology introduction expenditure, as a proxy for absorptive capacity. Higher values indicate a lower absorptive capacity. The number of S&T institutions established by domestic firms is used as a proxy variable for internal R&D. We construct an indicator of export resilience based on the exogenous shocks caused by the 2008 financial crisis (the sample period begins in 2009) measured as follows:

We control for industry–firm- and industry-level factors that may influence domestic firms’ innovation performance. At the industry–firm level, we control for the effects of capital intensity, export ratio, tax liability, and state capital share. At the industry level, we control for the effect of industry scale. The details are as follows: Capital intensity (KI) is the natural logarithm of the ratio of net fixed assets to the average number of employees. Export ratio (ER) is the value of export deliveries as a percentage of industrial sales. Tax liability (TL) is the sum of income taxes as a percentage of total profits. State capital share (SC) is the share of state and collective capital in paid-in capital. Industry scale (IS) is the natural logarithm of the average number of employees.

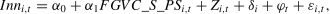

Estimation methodWe employed a panel data model to investigate the impact of MNEs’ participation in GVCs on domestic firms’ innovation performance because it can deal with data across industries and years by assuming that heterogeneity exists between industries and years. The Hausman test shows that a fixed-effects estimation is preferred for testing our hypotheses (chi-squared = 17.62, P = 0.0138), which is conducive to eliminate unobservable heterogeneity that remains constant over time. To address the problem of heteroscedasticity, we use robust standard errors for all estimations. Accordingly, the baseline model is as follows:

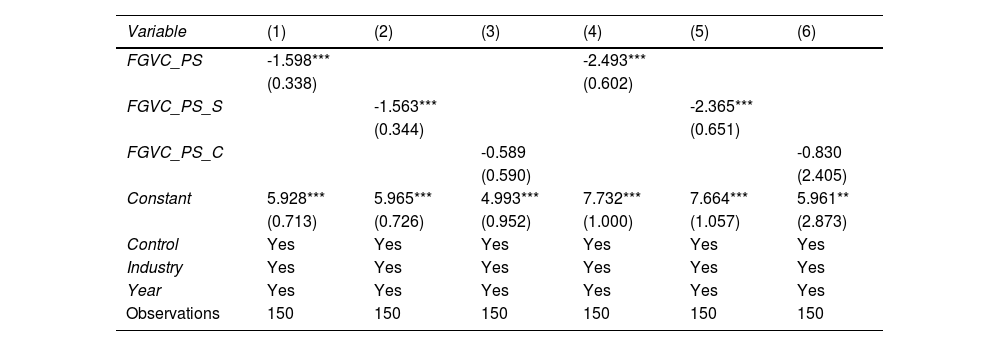

andwhere the subscript i denotes the industry and t denotes the year. δi and φt represent the industry- and year-fixed effects, and εit is the error term. Zi,t denotes the set of control variables.Empirical resultsMain analysisTable 1 presents the benchmark results and examines the impact of MNEs’ participation in GVCs on domestic firms’ innovation performance to test H1a and H1b. Columns (1)–(3) show the estimated results without the control variables. With the addition of the control variables, columns (4)–(6) indicate that the regression results are generally consistent.

Main analysis (Dependent variable: Innovation performance).

Note: Robust standard errors are indicated in parentheses. ⁎⁎⁎ p<0.01, ** p<0.05, and * p<0.1 (this applies to all tables in this study).

The more upstream MNEs participate in GVCs, the more negatively they affect domestic firms’ innovation performance. When the GVC index is larger, MNEs are closer to upstream GVC production. Conversely, MNEs are closer to the downstream GVC production. Column (4) shows that for domestic firms’ innovation performance, the coefficient of FGVC_PS is significantly negative at the 1% level. To further distinguish simple and complex GVCs, columns (5) and (6) present the impact of MNEs’ participation in simple and complex GVCs on domestic firms’ performance. The coefficients of FGVC_PS_S and FGVC_PS_C are significantly negative and nonsignificant, respectively, indicating that MNEs affect domestic firms’ innovation performance mainly through simple GVCs. Therefore, H1a and H1b are supported.

Robustness testWe conduct additional robustness tests for the findings presented in the benchmark estimations; Tables 2 and 3 present the results. First, we adopt alternate measures for the dependent and independent variables. Specifically, the number of invention patent applications as a share of the total patent applications is adopted to measure domestic firms’ innovation performance, and the trade decomposition approach (Wang et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2021) is applied to calculate MNEs’ participation in GVCs. Given the limitations of the trade decomposition approach, we cannot distinguish between simple and complex GVCs. The estimated results are presented in column (1) (Table 2).

Robustness test (Indicator replacement and the PPML model).

Robustness test (Endogeneity treatment).

Second, we use the Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood (PPML) model for regression. Given that the left-truncated data in the indicator of innovation performance in the benchmark regression is greater than zero, and E[ln(Y)]≠ln[E(Y)] may be true because of the logarithmic operation, the PPML model can solve the above problems. The regression results are presented in columns (2)–(4) (Table 2).

Third, we exclude reverse causality, which causes endogeneity, by lagging the independent variables and all control variables in columns (1)–(3) (Table 3). Additionally, we use the one-period lag of the core explanatory variable as an instrumental variable in columns (4)–(6) (Table 3). Considering endogeneity, the regression results show that the coefficient of the core explanatory variable is still robustly negative and increases significantly in absolute terms compared with the baseline regression. The negative effect of MNEs’ positions within GVCs on domestic firms’ innovation performance is underestimated if endogeneity is not controlled. To ensure the reasonableness of the selected instrumental variable, we conduct a weak identification test. The reported significance (p-value) of the instrumental variables in the first stage is significantly less than 1%, indicating that the problem of weak instrumental variables is obscure in our regressions.

Heterogeneity analysisTo investigate whether firm heterogeneity exists in the impact of MNEs’ participation in GVCs on domestic firms’ innovation performance, we perform heterogeneity tests according to domestic firms’ R&D intensity and RCA. Specifically, this analysis is based on the 50% quantiles of each variable. In each test, we distinguish between simple and complex GVCs.

In Table 4, columns (1)–(3) show that the coefficient of FGVC_PS_C is positive at the 5% significance level, whereas the coefficients of FGVC_PS and FGVC_PS_S are nonsignificant. Columns (4)–(6) indicate that the coefficients of FGVC_PS, FGVC_PS_S, and FGVC_PS_C are negative and statistically significant. We find that the negative effect of MNEs’ participation in upstream GVCs mainly affects domestic firms with high R&D intensity, whereas MNEs’ participation in complex upstream GVCs generates a positive impact. As domestic firms face difficulties in complex GVCs owing to technological barriers, MNEs generate demonstration effects. However, MNEs’ participation in upstream GVCs causes domestic firms to rely on MNEs and substitute them for independent R&D.

Heterogeneity analysis (R&D intensity).

In Table 5, columns (1)–(3) show that the coefficients of FGVC_PS and FGVC_PS_S are negative at the 5% significance level, whereas the coefficient of FGVC_PS_C is positive at the 10% significance level. Columns (4)–(6) show that the coefficients of FGVC_PS, FGVC_PS_S, and FGVC_PS_C are negative and statistically significant. Similarly, MNEs’ participation in upstream complex GVCs benefits domestic firms characterized by low RCA to some extent, whereas domestic firms characterized by high RCA are negatively affected by MNEs’ upstream participation in GVCs. Considering Tables 4 and 5, domestic firms with low R&D intensity and RCA do not benefit from complex GVCs organized and dominated by MNEs through backward linkages, as complex GVCs are characterized by high barriers to entry.

Heterogeneity analysis (RCA).

This section reveals that firm heterogeneity is important in determining whether the impact is significant by incorporating the dichotomy of simple and complex GVCs, although the regression results for complex GVCs are uncertain in the main analysis.

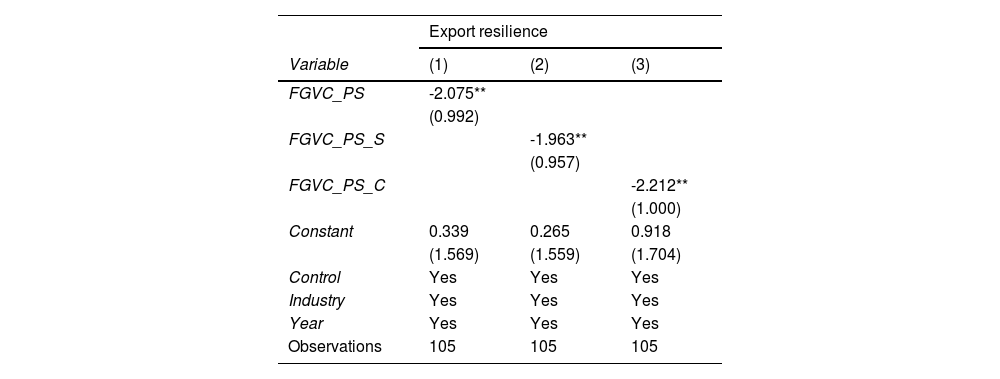

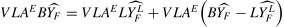

Mechanism identificationThis study specifies the theoretical mechanisms through which MNEs’ participation in GVCs affects domestic firms’ innovation performance and shows that domestic firms’ absorptive capacity, internal R&D, and export resilience are the key variables behind these mechanisms. The mechanism identification technique used in this study focuses on the causality between the core explanatory and mediating variables when the impact of the mediating variable on the dependent variable is direct and evident.

Table 6 examines the impact of MNEs’ participation on domestic firms’ absorption capacity and internal R&D. As we use absorptive cost to measure absorptive capacity, an increase in absorptive cost indicates a decrease in absorptive capacity. Innovation performance is negatively affected when absorptive costs increase. Without distinguishing between simple and complex GVCs, column (1) shows that the coefficient of FGVC_PS is positive at the 1% significance level for domestic firms’ absorption capacity, whereas column (4) shows that the coefficient of FGVC_PS is negative at the significance level for domestic firms’ internal R&D. To further distinguish between simple and complex GVCs, columns (2) and (3) show that only the coefficient of FGVC_PS_S is significantly negative for domestic firms’ absorption capacity, whereas columns (5) and (6) show that only the coefficient of FGVC_PS_S is significantly negative for domestic firms’ internal R&D. Therefore, H2a and H2b are supported.

Mechanism test (Absorption capacity and internal R&D).

Table 7 shows the impact of MNEs’ participation in GVCs on domestic firms’ export resilience. Column (1) shows that the coefficient of FGVC_PS is significantly negative for domestic firms’ export resilience. To further distinguish between simple and complex GVCs, columns (2) and (3) show that the coefficients of FGVC_PS_S and FGVC_PS_S are both negative at the 1% significance level for domestic firms’ export resilience. Therefore, H3a and H3b are supported.

In summary, the dichotomy between simple and complex GVCs is important, revealing that the roles of absorptive capacity and internal R&D in the relevant mechanisms are ambiguous if GVCs are highly complex, whereas the role of export resilience is clear. Specifically, an increase in GVC complexity insulates the flow of knowledge and technology and is inconducive to mitigate the dissemination process of risk and disruption. In brief, the positive spillovers generated by MNEs are obscure in complex GVCs, and the negative effects on export resilience are evident.

DiscussionResultsThis study demonstrates that MNEs’ downstream rather than upstream participation in GVCs is the main way to generate positive effects on domestic firms. This is similar to the findings of Javorcik (2004) and Lu et al. (2017). They observe that backward FDI positively affects domestic firms. This study shifts from the quantity and quality of FDI to the production activities related to FDI, especially the GVC production activities of MNEs.

To reveal how MNEs’ participation in GVCs affects domestic innovation, we consider domestic firms’ absorption capacity, internal R&D, and export resilience as the mediating variables. H1a and H1b propose that MNEs’ downstream participation in simple GVCs positively affects domestic firms’ innovation performance. This reflects an analysis of MNEs’ complex structures and processes highlighted by Andrews et al. (2023). Moreover, this is consistent with Gao et al. (2021), who show that China's domestic firms play an active role in simple GVCs, whereas MNEs from developed countries dominate complex GVCs, indicating significance.

According to H2a and H2b, the more upstream MNEs participate in GVCs, the more negatively they affect domestic firms’ absorption capacity and internal R&D; these relationships are significant for simple GVCs. As in previous studies such as Zhang et al. (2010), greater absorption capacity facilitates the utilization of technologies and management practices adduced by foreign MNEs. Berchicci (2013) asserts that firms can maintain innovation performance if they retain a certain level of internal R&D activity.

H3a and H3b indicate that the more upstream MNEs participate in GVCs, the more negatively they affect domestic firms’ export resilience; this relationship is significant for both simple and complex GVCs. Therefore, comprehensively considering all the results, GVC complexity is inconducive to FDI technology spillovers and poses a greater risk to domestic firms. Gorodnichenko et al. (2020) identify positive spillovers from FDI and trade to domestic firms’ technology and product innovation.

Theoretical implicationsThis study reveals that the more upstream MNEs participate in GVCs, the more negatively they affect domestic firms’ innovation performance. This relationship mainly exists in simple GVCs. This study has several important theoretical implications.

First, GVC-related production plays a vital role in exploring MNEs and FDI. This study examines MNEs’ GVC participation and complexity. This combination of inside–out and outside–in perspectives echoes the findings of McWilliam et al. (2020) and Pananond et al. (2020). Both focus on the GVC governance theory to reflect the outside–in perspective by analyzing interfirm dyad relationships. The reason for this shift from interfirm governance structures to intercountry industrial connections is that the latter is a fundamental driver of MNEs entering host countries. Second, how MNEs participate in GVCs is crucial to assess the impact of FDI on domestic firms’ innovation. The FDI technology spillover is one of the most important external factors affecting domestic firms’ innovation. Thus, the production position of MNEs within simple and complex GVCs determines the technological characteristics and extent of FDI technology spillover to domestic firms. Finally, absorption capacity, internal R&D, and export resilience are the important channels through which MNEs affect domestic firms.

Practical implicationsBased on these findings, we identify the practical implications benefitting domestic Chinese firms’ innovation performance through MNEs’ participation in GVCs. First, managers of domestic firms can focus more on shifting from collaborating with MNEs in simple GVCs to mastering core technologies and dominating complex GVCs. Although domestic firms can expand their export scales through simple GVCs, the opportunities to accumulate advanced technologies are limited. Second, managers of domestic firms should consider absorption capacity, internal R&D, and export resilience, and the potential benefits and risks related to simple and complex GVCs. Finally, policymakers in developing countries should consider the heterogeneous GVC-related activities of MNEs. This affects how MNEs integrate domestic firms into fragmented global production and their production positions within the global division of labor.

Conclusions and limitationsThis study examines the impact of MNEs’ participation in simple and complex GVCs on domestic firms’ innovation performance. We conduct an empirical analysis of Chinese manufacturing industries. The benchmark results indicate a negative relationship between MNEs’ upstreamness in GVCs and domestic firms’ innovation performance, which also exists in simple GVCs. Heterogeneity tests indicate that R&D intensity is an important factor in this relationship. Although nonsignificant in the benchmark regressions, MNEs’ participation in complex GVCs has the opposite effect on different samples of domestic firms. The mechanism tests show that MNEs’ upstreamness in GVCs negatively affects domestic firms’ innovation performance by negatively affecting their absorption capacity, internal R&D, and export resilience.

This study makes several important theoretical contributions to the existing literature. First, it highlights the research focus on MNEs’ GVC-related production activities rather than the quantity and quality of FDI. Second, it enriches the literature on firm innovation by analyzing how MNEs’ participation in GVCs affects domestic firms’ innovation performance. Finally, it provides important theoretical insights into the role of domestic firms’ absorption capacity, internal R&D, and export resilience in the channels through which MNEs affect domestic firms.

This study has some limitations that can be addressed in future research. First, it examines MNEs’ GVC production activities from the perspective of GVC production position, that is, upstream and downstream GVC participation. Future studies should explore other important factors. For example, we recommend integrating interfirm governance theory and GVC complexity embodied in intercountry industrial connections. Second, developing countries are heterogeneous in many aspects (Estrin et al., 2018; Andrews & Meyer, 2023), indicating the need for caution when generalizing this study's results to other emerging countries with specific conditions. Future studies should analyze multiple countries. Finally, our sample is limited to manufacturing industries because of data limitations, although the internationalization of service industries is becoming important (Pisani & Ricart, 2016). Future research should investigate how MNEs organize their service industries and collaborate with domestic firms in developing countries.

CRediT authorship contribution statementLina Yu: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Zenghui Guo: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Jing Ning: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Conceptualization.

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (NSSFC) [grant number: 23BGJ027].

Industry classification in the AMNE database and China's national standards.