The industry organization theory in the early stage emphasizes the structure-conduct-performance (SCP) paradigm, indicating that industry characteristics and structure factors influence firm performance. Accompanied by technology development and the enhancement of innovation capabilities, the resource-based theory (RBT) has gradually attracted greater attention. Industry structure and competitive forces emphasize the role of external industrial environment factors in influencing a firm's strategic decision-making. Firms employ resources as their competitive advantage to adapt to the industrial environments and to shape the own performance.

This study uses hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) to integrate SCP and RBT and to analyze the different levels of effects on firm performance. The integrated theoretical framework suggests multi-level relationships between industry and firm dynamics. Specifically, industry-level factors include industry potential, scale, and dynamics that positively moderate firm-level competitive advantages (innovation resources, organizational resources, and slack resources) and firm performance. The research findings also reveal that industry competitiveness negatively moderates impacts on the relationship between firm competitive advantages and performance. The integration of both industry and firm competitive advantages shapes firm performance.

Debates about the external industrial environment or internal firm competitive advantages having more effectiveness on firm performance have attracted the attention of researchers, managers, and investors (Nayak et al., 2023; Lyu et al., 2022). The global information technology industry and digitalization innovation have rapidly developed, resulting in multinational enterprises adopting internationalization strategies in order to enter overseas markets and to expand their supply chains (Luo, 2022). For instance, abundant resources have flowed to Taiwan's semiconductor market, especially during the last decade. Taiwan Semiconductor Corporation (TSMC), as the top silicon foundry firm globally, has continued to grow and attract foreign direct investment, thereby facilitating industry sustainable innovation and development. Resource accumulation flows in any industry will reduce firms’ entry barriers. This implies that the increase accompanied by industrial competitiveness may lower a firm's competitive advantages. Hence, a question arises: Does the integration of industry organization (IO) and the resource-based theory (RBT) reveal reasons for why firm resources or industrial structure advantages do not always achieve superior firm performance?

IO focuses largely on the relevance of structure-conduct-performance (SCP), while RBT targets a firm's internal resource attributes and competitive advantages (Wang & Coff, 2022; Tang & Karim, 2021). Thus, early researchers often applied only one of these two theories for analysis (Lo, 2021; Lo & Liao, 2021). The traditional IO theory and economists suggest that market structure and industrial characteristics influence the nature of competitive processes (Bain, 1956), such as monopoly and price discrimination being regarded as determining factors of firm performance (Mann, 1966). Differently, RBT experts from the microeconomic level consider a firm's dynamic capability and isolating mechanisms as key points to increase specific resources, attributes, and sustainable innovation capabilities that drive its performance (Barney, 1991; Rumelt, 1991; Teece, 1996). Some scholars argued that dynamic capabilities as an extension of RBT are regarded as a bridge between IO and RBT. Rouse and Daellenbach (1999), McGahan and Porter (2003), and Thornhill (2006) found that there is a nested nature between industry-level and firm-level influences using random and fixed effect models.

Some studies in the literature have developed a framework that integrates the SCP paradigm and the RBT perspective to explain firm performance (Keskin et al., 2021), yet the mechanisms by which multi-competitive advantages impact performance still require further exploration. How the interaction between industry-level and firm-level factors influence performance remains unclear due to limitations in research methods. The theoretical framework integrating industry environmental advantages and firm resources to shape firm performance is not comprehensive. For instance, Keskin et al. (2021) proposed that the intensity of industry competition moderates a firm's unique capabilities and is considered an external factor that impacts firm performance. Morgan (2004) pointed out that an industry environmental venture mediates the relationship between firm resources and performance. Based on Morgan (2004) and Keskin et al. (2021), our study targets resource and advantage integration concerning industry-level environmental factors and firm-level competitive advantages.

This research explores the effect of the external industrial environment on the advantages of internal firm resources and firm performance. It further investigates the moderating role of industry potential, industry competitiveness, and industry scale, as well as industry dynamics in the relationships among a firm's innovation resources, organizational resources, slack resources, and performance. To do so we obtain primary data and samples from 769 Taiwan-listed companies covering 25 different sectors and secondary data from the Taiwan Economic Journal (TEJ). By testing the conceptual framework, we aim for a breakthrough via hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) and explore the relationship among multi-level competitive advantages and firm performance.

Our study makes three distinct contributions to the literature on strategy management. First, numerous studies do not integrate IO and RBT and only use one way to discuss industrial elements or the effect of resource advantages on firm performance. While some papers have acknowledged that the industrial environment and firms’ development have nested structures, the empirical studies are insufficient. For instance, Morgan (2004) and Keskin et al. (2021) focused on the combined effect of RBT and SCP, noting a firm's capabilities and industry competitive intensity on its own competitive strategies and advantages. We extend the findings of other studies by using HLM to examine industry attractiveness, competitiveness, dynamics, and scales as moderating roles influencing the relationship between firm competitive advantages and performance rather than by only considering competitive intensity.

Second, from the perspective of integrating RBT and SCP, our paper fills the gap in research methods of past theoretical concepts. Unlike ordinary least squares (OLS), HLM can handle unequal group sizes and unbalanced data and estimate the moderation effect for a nested data structure. Hence, we utilize a multi-level framework to integrate competitive advantages and simultaneously examine the interaction of how industry-level factors and firm-level competitive advantages affect firm performance.

Third, to the best of our knowledge, scant studies have investigated how external environmental factors moderate the relationship between firms’ internal resource advantages and performance. Our research not only focuses on a framework that reveals a combination of industry advantages and firm resources that shape firm performance, but also emphasizes how industry potential, competitiveness, scale, and dynamics moderate the relationship between competitive advantages and firm performance. According to our findings, firm-level competitive advantages significantly influence firm performance, and industry-level factors moderate the relationship between firm competitive advantages and firm performance. Industry competitiveness especially has a significantly negative impact on firm-level competitive advantages. This implies that the interaction between industry environmental advantages and a firm's competitive advantages does not necessarily mean the firm will achieve better performance. Firms should reduce the negative impact of industry competitiveness on their business and utilize the development potential, economic scale, and dynamic capabilities brought by industry structure advantages in order to improve their performance.

Literature review and hypothesesObserving firms’ market position is primarily based on two distinct aspects: the macroeconomic level and the influence of industrial environment factors. Traditional IO theory based on industrial structure advantages establishes the relevance path of an industry's environment factors and a firm's performance. The cornerstone of the SCP paradigm is that industry structure forms a specific external environment that influences the stakeholders and conduct of firms (Bain, 1956; Porter, 1980; Sheel, 2016).

The microeconomic level in turn focuses on the competitive advantage derived from a firm's innovative capabilities. Based on the RBT perspective, firm attributes and characteristics influence the economic scale and competitiveness of an industry (Barney, 1991; Teece, 1996; Connor, 2002; Wernerfelt, 2013). With the rapid development of technological innovation, increasingly numerous unicorn firms are emerging. For instance, the thriving Artificial Intelligence Generated Content-related industry chain is currently in the spotlight. It reveals a phenomenon that firm performance is closely tied to innovation, and becoming a black swan or a technology unicorn has become one path for firm development.

Returning to the classical definition of RBT only reveals that a firm's resources and capabilities can create sustainable competitive advantages (Heredia et al., 2022). It does not necessarily imply that obtaining internal firm competitive advantages will increase performance (Tippins & Sohi, 2003). Taking into account the SCP perspective, the external industry structure and dynamics play a crucial role in a firm obtaining specific resources (Ananda et al., 2016). How do the interaction of multi-level competitive advantages shape firm performance? First, different industries can have a strong correlation with each other, and cross-development expands their business activities more widely (Li et al., 2019). Second, a partial overlap between businesses increases the different dimensions’ competitive advantages for firm development (Nayak et al., 2023). Third, seeking higher profit forces firms to increase their market competitiveness, revealing that industry has development potential (Audretsch et al., 2001). Thus, we infer based on multi-level competitive advantage that there is a complementary relationship between competitive advantages at the firm level and industry level.

Direct effects of firm-level competitive advantagesThe literature has discussed the source of competitive advantages separately from the isolation mechanism (Rumelt, 1991), resource attribute (Barney, 1991), causal ambiguity (Dierickx & Cool, 1989), and dynamic capability (Teece, 1996). Numerous studies have suggested that a firm's competitive advantage influences its performance.

Based on RBT whereby heterogeneous resources form the sustained competitive advantages of a firm, Barney (1991) emphasized the links among firm resources, capability, and firm performance. Liu and Huang (2018) suggested that a firm's dynamic competence and internal competitive advantage are potent factors affecting its performance. A firm's sustainable competitive advantage also helps form its business strategy and facilitates creating its performance (Davcik & Sharma, 2016). The relationship between a firm's competitive advantages and performance is so close that they can improve each other.

We thus follow the RBT perspective and separate firm-level competitive advantages into innovation resources, organizational resources, and slack resources. Drawing on the literature on the direct effect of a firm's competitive advantage, our research explores the relationship between multi-level competitive advantages and firm performance, especially focusing on the moderation effects of the external industrial environment. In what follows, this study discusses the three aspects in more details.

Innovation resources advantage and firm performanceBased on the RBT perspective, innovation advantage involves a lot of knowledge endowment, but has imitation barriers (Capello & Lenzi, 2018). For instance, based on innovation and technology transfer, Tolentino (2017) suggested that heterogeneity innovation means renewal and expansion of a resource that can beneficially influence firm performance. Jiang et al. (2010) indicated that a diversity of innovation advantages positively influences firm performance from two dimensions: a firm's breadth and depth. Similarly, Ndofor et al. (2011) proposed that the unique characteristics of innovation resources and capabilities provide greater resource breadth, which allows firms to obtain a greater competitive advantage. Hence, innovation resources as an intangible are scarce, valuable, non-imitable, and non-substitutable and increase firm performance (Ghapanchi et al., 2014; Nguyen-Anh et al., 2022).

Innovation resources essentially imply the various inputs that a firm makes in seeking technological breakthroughs. They encompass the key elements of production, sales, human resources, research and development, finance, etc. A higher innovation resource input-output ratio comes from sustainable innovation capabilities and more effective resource allocation (Davis-Sramek et al., 2015). Numerous researchers have considered that R&D investment and providing process innovation, green innovation, product innovation, digital innovation, business model innovation, and the construction of technological innovation platforms can all enhance the efficiency of innovation resources utilization and improve firm performance (Candi & Beltagui, 2019; Leal-Rodríguez et al., 2015; Sun & Hu, 2022; Wang et al., 2020). Thus, we have the first hypothesis as follows.

H1a

Innovation resources advantage positively influences firm performance.

Organizational resources advantage and firm performanceInnovation capability is a fundamental part of organizational resources. From the perspective of firm growth, substantial redundant resources and sunk cost input are required to ensure that a firm can seize opportunities during periods of rapid growth without relying on resource allocation and performance issues (Sterk et al., 2021). In more detail, when the firm is entering a rapid growth phase, its performance will increase depending on how abundant its slack resources are. Barney & Wright (1998) noted that organizational advantage increases firm performance. Lau et al. (2010) considered that organizational resources include both tangible and intangible resources; tangible resources are like a firm's capital or assets, while intangible resources are like thoughts of innovation or creativity by an employee. For instance, developing a corporate culture can be regarded as an intangible resource that encourages creative thinking and helps improve firm performance (Leal-Rodríguez et al., 2015).

Organizational resource endowments improve firm performance by reconfiguring resource combinations, reallocating capabilities, and adopting new ways of capability utilization (Heredia et al., 2022). This results in numerous firms being keen on hiring high-level human resources and extending their scale. Doing so not only enhances the organizational advantage, but also facilitates their operations and their development to obtain sustainable competitive advantages. Integrating heterogeneous competitive advantages of a firm's scale, human resources, and firm reputation can be a driving force to improve firm performance. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis.

H1b

Organizational resources advantage positively influences firm performance.

Slack resources and firm performanceUnlike organizational resources, slack resources are not a direct competitive advantage for a firm. However, from the perspective of firm growth, slack resources often play a positive role in its innovation and development (Audretsch et al., 2014). Considering the impact of industry dynamics on firm innovation, leveraging slack resources can effectively reduce management risks and expand competitive advantages. Vanacker et al. (2016) highlighted within a firm that slack resource plays an important role. Accordingly, Bourgeois & Singh. (1983) indicated under a curvilinear slack-performance relationship that slack is regarded as an important non-strategic competitive advantage and provides resources for organizations. It is not only a resource endowment for an enterprise, but may also allow it to increase performance under more slack resources (Vanacker et al., 2016). Hence, firm-specific resources and the difficulty of a technological imitation increase can be regarded as innovation drivers relying upon slack resources (Terziovski, 2010).

A deeper discussion of a cognitive slack resource also includes contrasting the importance of absorbed and unabsorbed slacks when firms sustain and create their competitive advantages (Su et al., 2009). For instance, Fadol et al. (2015) proposed that the influence of an unabsorbed slack on an organization's performance is more critical than that of an absorbed slack. Luo et al. (2016) claimed that unabsorbed slack provides firms with additional available resources and improves their performance. Accordingly, the next hypothesis runs as follows.

H1c

Slack resources positively influence firm performance.

Moderation effects of industry-level competitive advantagesThere are abundant studies discussing firm competitive advantages’ or industrial environment advantages’ impact on firm performance. For instance, Tolentino (2017) presented evidence of a positive relationship between firm competitive advantages and performance. Wu et al. (2017) revealed that industrial environment competitiveness affects the strength of a firm's innovation ability. However, empirical studies on industry-level factors that influence firm performance relied on the traditional structure performance form of the SCP paradigm. There is less research on whether external industry environmental factors may moderate the relationship between firm competitive advantages and performance, such as industry scale, industry competitiveness, and issues of demand and supply. These external environmental factors influence the firms’ product diversity and capabilities of resource integration, further affecting their performance. Thus, we infer that the relationship between firm-level competitive advantages and performance can be moderated by industrial environment factors. In other words, the relationship between multi-level competitive advantages and firm performance may change under the moderating effect of external industry environmental factors.

Based on the IO theory, traditional SCP (Structure-Conduct-Performance) views emphasize external forces as important effects on firm performance. For instance, Porter (1980) proposed the five forces framework to analyze how industrial structure influences a firm's competitive strategy. The collective effects of the five forces determine the potentiality and competitiveness of the industry (Conner, 1991), while differentiation competition facilitates market dynamicity of the industry. Nowadays, globalized industrial chains prosperously develop, and various links in them are intricately intertwined, which make it difficult to survive when an industry is in isolation. Therefore, different industries should maintain dynamism and innovation capabilities to expand their industrial scale. Lyu et al. (2022) considered the scale effect on industry growth to be positive, and if the labor force increases, then the scale affects the firm performance. Industry scale and dynamics are determinant barriers to the entry or exit of firms. Hence, we follow the IO theory and separate industry-level competitive advantages into industry potential, industry competitiveness, industry scale, and industry dynamics. In more detail as follows, this study discusses these four aspects.

Industry potential moderates firm-level competitive advantagesFrom the industry structure perspective, a high-potential industry has short-run entry inducements for firms (Caves, 1998). Among these factors, transaction costs, technical development, and the relationship between monopoly and competition become key drivers affecting firm-specific resources and innovation capabilities (Porter, 1980; Noponen et al., 1997; Carlton, 2020). An industry with great profits and market growth expectations can provide more resources and opportunities for firms to increase innovation capability, whereas heterogeneous competition facilitates improved firm performance due to industry's internal increased demand. Similarly, Bell and Pavitt (1997) found that the potential advantages of industry are for not only performance, but also for the general and positive effect on the mobility of firm resources. For instance, knowledge sharing or technology transfer facilitates different firms to integrate resources that form sustainable competitive advantages (Gilbert, 1989).

In promising industries firms seeking survival positions will chase higher value to capture a market. Utilizing industrial resource advantages to expand products or high-quality services can improve firm performance. Industry potential facilitates in the development of firms’ resources and capability, even expanding organization slack. Hence, we infer that industry potential moderates the firm-level resources endowment. Accordingly, our research proposes the following hypothesis.

H2a

The relationship between firm-level competitive advantages and firm performance is positively moderated by industry potential.

Industry competitiveness moderates firm-level competitive advantagesIn contrast with industry potential, increases in industrial competitiveness will decrease a firm's competitive advantages. The globalization development trend of supply chains reveals that more and more industries cannot just rely on their home country resources. For instance, digital information-related industries are expanding in the global market. Therefore, industry competitiveness, defined as the ability to produce and export competitively manufactured goods, is a crucial driver for firms seeking more resources that are advanced (Zhang, 2014). Industries with competitiveness are like an internationalization platform, leading domestic firms to go abroad seeking innovation resources to raise their profit-making space, diversification, and performance.

The motivation of firms’ export-oriented decision-making is usually due to internal market competitive pressure. When the industry is regarded as having a competitive advantage, it means numerous firms are forced to sustainably improve production efficiency and provide stable supply chains (Kwon & Motohashi., 2017). Therefore, influenced by the external environment advantage of industrial competitiveness, the firm will face more pressure to capture resources, keep innovation capability, and through optimal strategic decisions improve its performance (Guan et al., 2006). According to the concept of contestable markets, an industry with only a few firms or even just one firm can still be competitive if there is a threat of entry from other firms. At the same time, firms in the market not only have monopoly competition, but also threats from other industries and supply chain substitution pressures (Mazur et al., 2016; Du et al., 2020; Durand & Milberg, 2020). Thus, we infer firms’ specific resources are effectively moderated by industry competitiveness and propose the following hypothesis.

H2b

The relationship between firm-level competitive advantages and firm performance is negatively moderated by industry competitiveness.

Industry scale moderates firm-level competitive advantagesIndustry scale implies abundant production capacity, well-developed infrastructure, and a complete supply chain. Bianchi et al. (2014) reported results from the moderating effects of industrial scale, competitive intensity, and technological turbulence on firm performance. Furthermore, they considered evidence that industrial scale affects a firm's core competitive ability. They argued that enlarging industrial scale facilitates the firm to develop its specific resources and irreplaceable innovation advantage.

From the perspective of integrating SCP and RBT, industry scale provides abundant opportunities for firms’ innovation, reduces the cost of R&D and production, and enhances their profit margins (Haiyan et al., 2021). Hence, industrial scale not only affects a firm's innovation resource advantages, but also influences the organizational structure and business model (Wu, 2010). For instance, startup firms have limited resources to flatten their organization and rely on complete supply chains of industry scale, while a business group company has abundant resources and research development capabilities under its own integrated supply system. Hence, large-scale industries find it easier to inspire firm innovation motivation compared to smaller-scale industries. In other words, a greater industrial scale denotes stronger innovation demand that a firm faces (Lin, 2014). Similarly, Doronina et al. (2016) revealed that industry scale, industrial profitability, and cross-enterprise/organization cooperation enhance a firm's high-quality development of human resources and innovation capabilities. Accordingly, we present the next hypothesis.

H2c

The relationship between firm-level competitive advantages and firm performance is positively moderated by industry scale.

Industry dynamics moderate firm-level competitive advantagesIndustrial dynamics imply a process of evolution and cluster development of firms, whereby they move from entry into the industry to rapid growth, then gradual maturity, and finally exit. In more detail, an active industry inevitably leads to the emergence of firm clusters and competition. Hence, Mathews (2002) found that the process of industrial transformation forces structural change on firm growth. The higher barriers to imitation and innovative capabilities are more likely to offer a competitive advantage and help secure specific resources for a firm. In turn, firms lacking competitiveness may face elimination from the industry, thus serving as the cornerstone for maintaining economic vitality in the market.

If firms survive after coping with vast amounts of industrial turbulence, then industrial dynamics will force them to enhance their technical resources and innovative capabilities. Hence, an industry with more turbulence not only implies higher dynamics, but it also can be regarded as offering more chances for enterprises. Similarly, Chang et al. (2015) proposed that the industrial dynamics formed between firms’ competition are a potential impact factor for new technologies and innovation intensity, further changing the resource usage and environmental opportunity/threat. Thus, our research has the following hypothesis.

H2d

The relationship between firm-level competitive advantages and firm performance is positively moderated by industry dynamics.

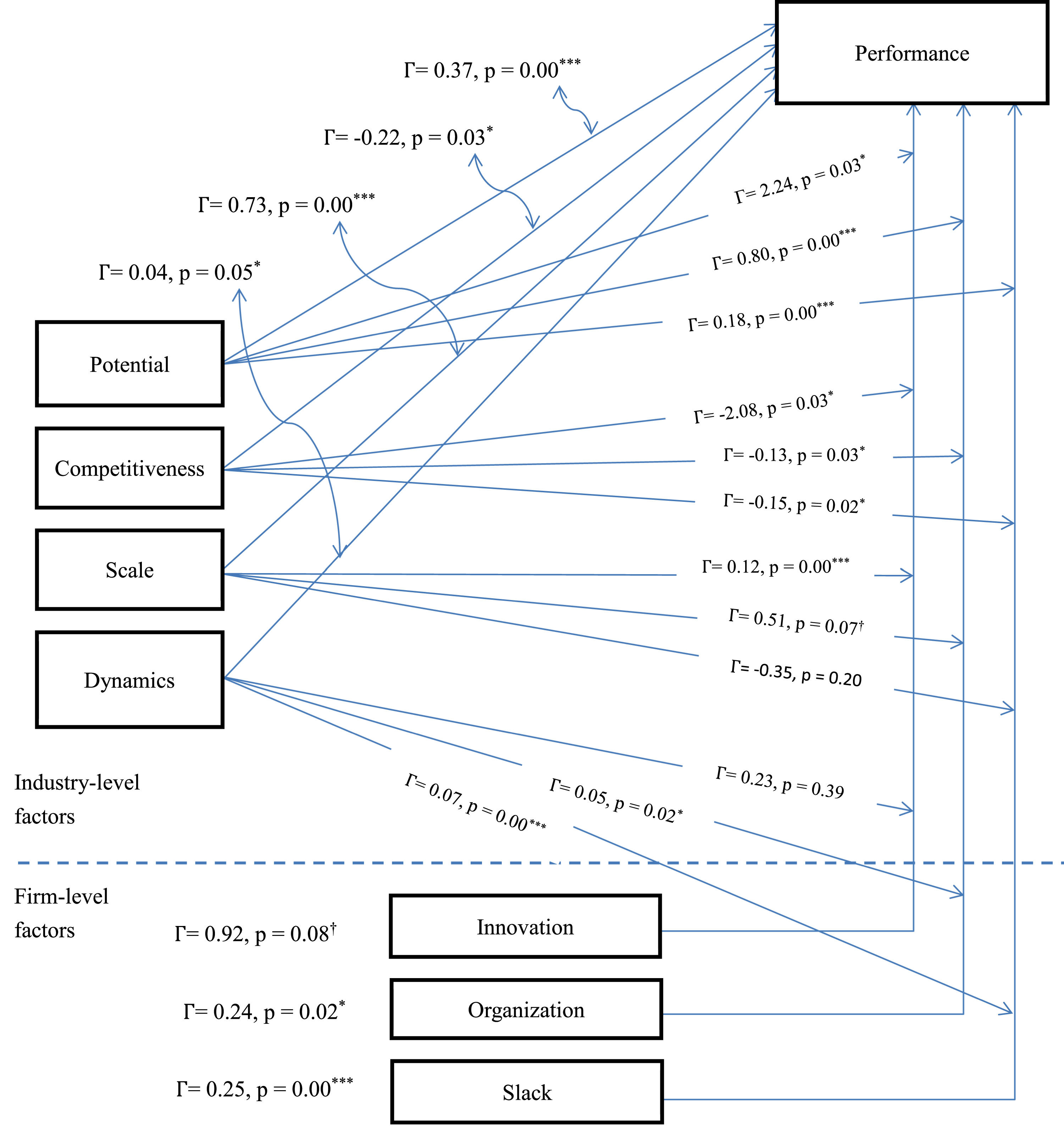

Research methodFrameworkLevel 1: This research investigates the relationship between firm competitive advantage and firm performance. Firm-level competitive advantages involve innovation resources, organizational resources, and slack resources.

Level 2: This research investigates the moderating role of industrial factors on firm performance. It examines the influence of industrial environment advantages on firm competitive advantages. An industrial advantage involves industry potential, industry competitiveness, industry scale, and industry dynamics. Fig. 1 illustrates the framework.

Analysis methodThis study explores the synergistic effects of industrial environment factors and firm competitive advantages on firm performance and utilizes hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) for analysis. It further observes the moderating role of the industry-level elements on the relationship between firm competitive advantages and performance. Therefore, the selected sample needs to include companies of a certain scale with complete financial reports. There is a total of 816 listed companies in Taiwan as of 2024. Considering the differences in accounting standards between the financial and insurance industries and general enterprises, the former are excluded from the sample. Additionally, industries such as electricity and gas supply, water supply, and pollution control, which are typically government public utilities, are also excluded as they do not meet the research requirements. We thus collect data from an innovation-related industry chain of 769 Taiwan-listed companies from the Taiwan Economic Journal (TEJ) database and include companies with complete financial reports covering 25 industry categories, including manufacturing, construction, retail, tourism, media, and services.

We next define firm-level data as being lower level and industry-level data as being higher level. We then further crosscheck the annual reports of the sample companies from the Market Observation Post System (MOPS) to ensure credibility and precision of data collection.

A moderation effect implies that the moderator variables (industry-level environment factors) modify the form of the relationship between the predictor variables (firm-level competitive advantages) and the criterion variable (firm performance). Our research analyses adopt HLM not only because it can examine different levels at the same time (Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992), but also through each level it employs one regression to examine the factor of variance, which is sufficient to prove the results are correct and rational (Bryk et al., 1996).

Considering the model's robustness, this study increases the direct effect between industry-level variables and firm performance as a control effect in the full model. Thus, the research utilizes the software HLM 6.0 to examine the four models. The first model is the null model to examine the multi-level effect. The second model is the random intercept model to investigate the relationship between the independent variables at the firm level and the dependent variable. The third model is the intercept-as-outcome model, which examines the industry level as explained by the intercept. The fourth model examines the multi-level moderation effect, which allows us to see whether different levels are moderated.

MeasurementDependent variableFirm performanceThe dependent variable covers the performance of Taiwan-listed companies. We follow Girod and Whittington's (2017) suggestion and utilize Tobin's Q as a measure of firm performance, because it is an indicator of firm growth opportunities. A high Tobin's Q indicates that a firm has opportunities and potential for future profitability. It suggests that the market values the firm's assets in anticipation of future earnings. Hence, firm performance is calculated as the market value of firm i divided by the replacement cost of capital and is denoted by:

Independent variablesLevel 1Innovation resourcesOther studies based on RBT have utilized R&D expenditure to measure innovation resources (Li-Ying et al., 2016). In this study we adopt R&D intensity to measure a firm's innovation resources. Based on the context of knowledge sharing and encouraging innovation, higher R&D intensity facilitates creating a firm's competitive advantage (Wu et al., 2017). Sustainable expenditure in innovation helps firms develop unique capabilities and specific resources. High-quality service and products can form intellectual property barriers to set a firm apart from competitors. Hence, we follow Qian et al. (2018) to define RDI (R&D intensity) as firm i R&D expenditure divided by total capital, denoted by:

Organizational resourcesOrganizational resources are regarded as a firm's intangible advantage, which include intellectual property, the value of reputation, and human capital, usually measured by the number of employees (Neves et al., 2017). Because employees represent the skills, knowledge, and expertise of the firms’ value, their co-production contributes to the organization's intellectual resources and capabilities. Considering avoiding multiple mutual linear problems, we adopt a logarithm of the number of employees in firm i to measure organizational resources. It is denoted by:

Slack resourcesAccording to the firm growth view, more slack resources are better. Slack resources are optimized sunk capital, including inventory, production capacity, equipment, and technology. However, on the supply chain safety and stock side, a firm can free up working capital that was previously tied up in stock by reducing inventories. For instance, Taiwan manufacturers have reduced production to adjust their inventory, to cope with the dynamic supply and demand balance of industries. While a firm solves the problem of overstocking by reducing excess production capacity, it can improve the efficiency of resource allocation and capital turnover rate. Hence, George (2005) proposed that firms with larger slack resource endowments are more likely to have lower inventories, thus reducing supply chain risk.

We modify Bradley et al. (2011) and multiply inventory by “-1″, representing reduced inventory so as to measure a firm's slack resource.

Level 2Industry potentialFrom time to time, innovative thinking and entrepreneurship lead to the development of industry trajectories that promote industrial upgrading. A high-potential industry is composed of abundant innovation organizations and firms. Therefore, given the pace of changes in a competitive landscape, firms’ profitability is a key factor, implying that a consistently profitable industry with healthy profit margins is more likely to attract entrepreneurs and startups to enter compared to one with unstable or lower profitability (Nielsen, 2015; Gilbert, 1989; Porter, 1980).

The profitability of firms within an industry can indicate the overall profitability potential of the industry. For instance, when most firms are profitable, it suggests that market demand and products or services are favorable for the industry. Hence, we follow the literature that utilizes the total industry profitability ratio to measure industry potentiality (Dierickx & Cool, 1989). The equation is:

Industry competitivenessThe literature has suggested that considering exclusively linked industrial competitive environment and firm performance and only focusing on the relative factors of industrial competitiveness and firm advantage will better reveal that the monopoly phenomenon may exist (Davis & Orhangazi, 2021). Development opportunities, resources, and pioneering advantages are most apparent in a firm that enters the industry first. In comparison with industry peers, oligopoly firms with larger total assets may have more resources at their disposal for innovation research design, marketing strategy, and acquisitions (Appelbaum & Lim, 1982). On the one hand, more firms that are competitive can buy out or merge with competitors, thus relying on their substantial assets. This increases industry barriers. On the other hand, firms with smaller assets must pursue growth opportunities by seeking short- or long-term loans to avoid becoming acquisition targets. Hence, total firm assets within an industry are indicative of industrial competitiveness.

We thus follow Hundley and Jacobson (1998) view. We sum the total assets of the 769 listed companies and divide them into 25 industries for our industrial competitiveness variables’ measure according to the definition of TEJ's industry division. The equation is:

Industry scaleAccording to analysis of industrial cluster studies, from a long-term life cycle perspective startups emerge and grow over time (Frenken et al., 2015). In other words, firm entry and survival result from industrial-scale expansion. If most new entry firms emerge and can survive in the short term, then this indicates the developing trend of industry scale. If numerous firms can survive over the long term, then this implies that industry scale is stable. Hence, the literature has noted a strong association between industry clustering and firm entry or quit (Delgado et al., 2010).

Industry scale is measured by a cluster, in which the number of cluster firms reflects the size of such scale (Tang, 2015). Thus, we use this measure.

Industry dynamicsExploring industry dynamics are usually based on survival analysis, which involves the modeling of time-to-event data (Papageorgiou et al., 2019). In this context, a firm's entry and exit are considered important time points in survival analysis. Hence, we measure a firm's age of survival to understand operational and development experiences in an industry. To do so, this study needs to evaluate industrial structure change, such as the uncertain duration of firm survival.

In more detail, industry dynamics represent the survival status of firms in an industry. To calculate the industrial experience of a company, we subtract the founding year of the firm from the research year (Kleynhans, 2016). Moreover, we adopt the variable's standard deviation to measure industry dynamics.

Estimation methodsFollowing the methodology to analyze the multi-level data structure from Chang et al. (2022), we test these hypotheses with HLM due to the nature of nested data. A hierarchical linear model (HLM) is a statistical specification that explicitly recognizes multiple levels in data. HLM can fit models to outcome variables that generate a linear model with explanatory variables that account for variations at each level. Multi-level analysis refers broadly to the methodology of research questions and data structures that involve more than one type of unit. In this research, we adopt grand mean-centered to interpret the HLM results and to estimate the level 1 (Firm) effects for examining the moderating effects of the level 2 (Industry) variables and the decrease of multicollinearity in level 2 estimates (Chang et al., 2022). Thus, the role of each variable in the framework is to explain the interaction of multi-level competitive advantages that shape firm performance.

Null modelTo check whether there is any difference between industry level and firm level on the dependent variable, we adopt a one-way analysis of variance to check whether HLM is appropriate. In addition, we compute the degrees of variance for both firm and industry levels by using the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) to calculate R2. The null model equation is established below.

Level-1 Model:

Level-2 Model:

ICC is computed as:

Random intercepts modelWe utilize HLM to test the relationship between the independent variables at level 1 and the dependent variable. More accurate estimates of the intercepts are calculated in this model. The equations for the random intercepts model are as follows.

Level-1 Model:

Level-2 Model:

Intercept-as-outcome modelThe intercept-as-outcome model examines level 2′s effect on the dependence variable, and whether it can efficiently explain the results. Based on multi-level competitive advantages, this research investigates an industrial competitive advantage's direct effect on firm performance. The industry-level variables involve industry potential, industrial competitiveness, and industrial scale as well as industrial dynamics. The model is as follows.

Level-1 Model:

Level-2 Model:

Multi-level moderated modelThe multi-level moderated model investigates a different level's effect on other levels. In other words, this research examines the moderating effect and discusses the relationship between level 1 and firm performance as moderated by level 2. The model is established as follows.

Level-1 Model:

Level-2 Model:

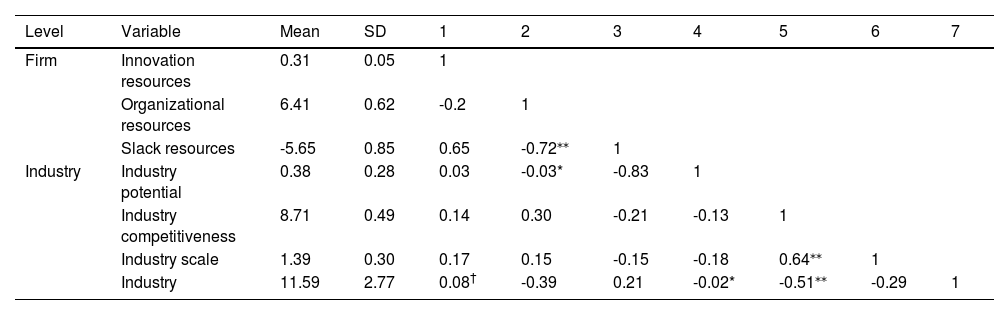

Empirical resultsDescriptive statisticsTable 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlations of all variables in this study.

Means, standard deviations, and pearson correlations.

| Level | Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firm | Innovation resources | 0.31 | 0.05 | 1 | ||||||

| Organizational resources | 6.41 | 0.62 | -0.2 | 1 | ||||||

| Slack resources | -5.65 | 0.85 | 0.65 | -0.72⁎⁎ | 1 | |||||

| Industry | Industry potential | 0.38 | 0.28 | 0.03 | -0.03* | -0.83 | 1 | |||

| Industry competitiveness | 8.71 | 0.49 | 0.14 | 0.30 | -0.21 | -0.13 | 1 | |||

| Industry scale | 1.39 | 0.30 | 0.17 | 0.15 | -0.15 | -0.18 | 0.64⁎⁎ | 1 | ||

| Industry | 11.59 | 2.77 | 0.08† | -0.39 | 0.21 | -0.02* | -0.51⁎⁎ | -0.29 | 1 |

According to Eqs. (1) and (2), we obtain the null model of HLM (see Table 2). We notice that the variance inflation factor (VIF; results available upon request) of all variables is less than 10. Hence, we conclude no serious multicollinearity among all independent variables.

We calculate ICC (see Table 1) by using ρ=0.4250.425+0.628=0.40361 from Eq. (3). Cohen (1988) suggested that if ICC is greater than 0.138, then there is high intra-class correlation among different-level variables being used in the data and a difference exists among multi-level competitive advantages as well as the suitableness of HLM.

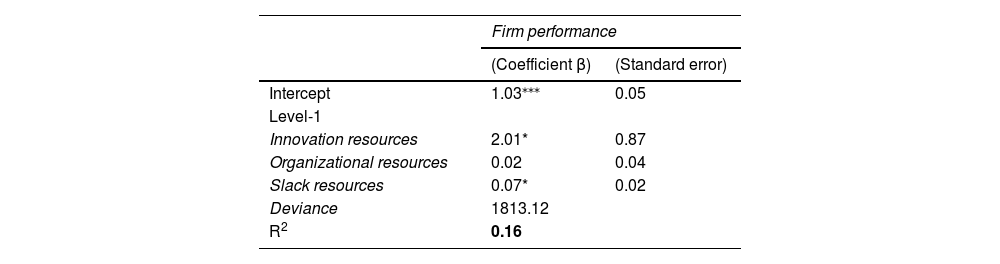

Random intercepts modelTable 3 shows the results of the random intercepts model, which indicate that innovation resources significantly positively relate to firm performance (β=2.01, p<0.05). Slack resources also significantly positively relate to firm performance (β=0.07, p<0.05). However, organizational resources do not significantly relate to firm performance (β=0.02, ns.). Compared to the null model, the independent variables at level-1 explain 16% (R2=0.16) of the variance in firm performance.

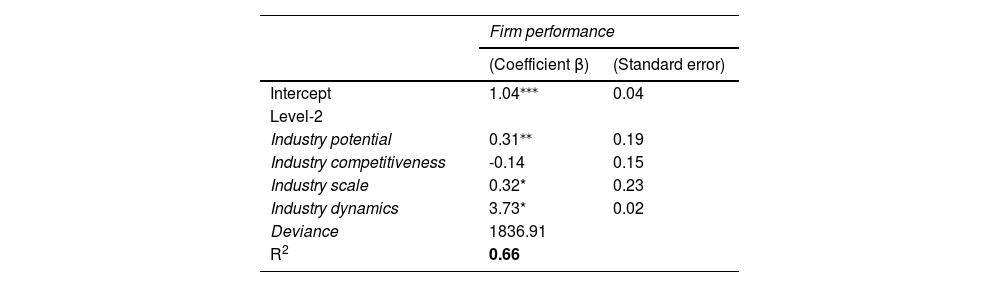

Intercept-as-outcome modelTable 4 shows the results of the intercept-as-outcome model. The results indicate that industry potential significantly positively relates to firm performance (β=0.31, p<0.01). Industry scale also significantly positively relates to firm performance (β=0.32, p<0.05). In addition, industry dynamics significantly positively relate to firm performance (β=3.73, p<0.05), while industry competitiveness insignificantly relates to firm performance (β= -0.14, ns.). Compared to the null model, the independent variables at level-2 explain 66% (R2=0.66) of the variance in firm performance.

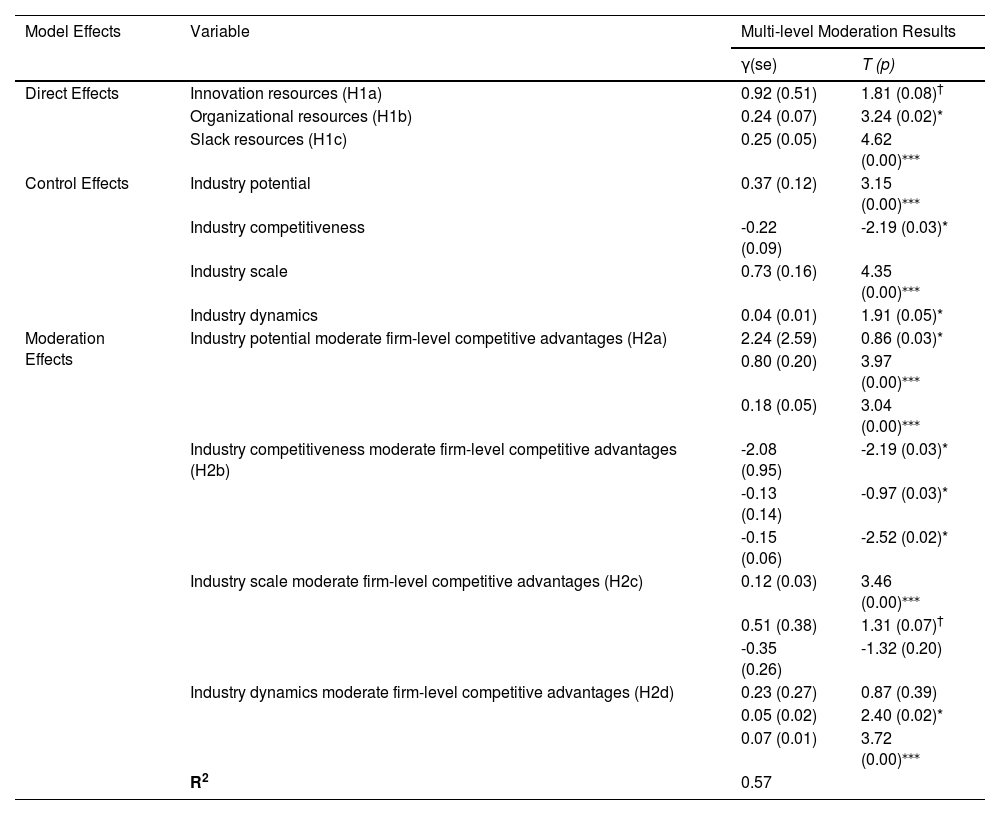

Multi-level moderated modelFrom the results in Table 5 and Fig. 2, we observe that the relationship between firm-level competitive advantages and firm performance is partially significantly moderated by industrial environment factors. We note that although firm performance becomes better when the firm-level competitive advantages are moderated by the industrial environment factors, industrial competitiveness significantly negatively moderates the relationship between firm-level competitive advantages and performance.

Results of the multi-level moderated model.

| Model Effects | Variable | Multi-level Moderation Results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| γ(se) | T (p) | ||

| Direct Effects | Innovation resources (H1a) | 0.92 (0.51) | 1.81 (0.08)† |

| Organizational resources (H1b) | 0.24 (0.07) | 3.24 (0.02)* | |

| Slack resources (H1c) | 0.25 (0.05) | 4.62 (0.00)⁎⁎⁎ | |

| Control Effects | Industry potential | 0.37 (0.12) | 3.15 (0.00)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Industry competitiveness | -0.22 (0.09) | -2.19 (0.03)* | |

| Industry scale | 0.73 (0.16) | 4.35 (0.00)⁎⁎⁎ | |

| Industry dynamics | 0.04 (0.01) | 1.91 (0.05)* | |

| Moderation Effects | Industry potential moderate firm-level competitive advantages (H2a) | 2.24 (2.59) | 0.86 (0.03)* |

| 0.80 (0.20) | 3.97 (0.00)⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| 0.18 (0.05) | 3.04 (0.00)⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| Industry competitiveness moderate firm-level competitive advantages (H2b) | -2.08 (0.95) | -2.19 (0.03)* | |

| -0.13 (0.14) | -0.97 (0.03)* | ||

| -0.15 (0.06) | -2.52 (0.02)* | ||

| Industry scale moderate firm-level competitive advantages (H2c) | 0.12 (0.03) | 3.46 (0.00)⁎⁎⁎ | |

| 0.51 (0.38) | 1.31 (0.07)† | ||

| -0.35 (0.26) | -1.32 (0.20) | ||

| Industry dynamics moderate firm-level competitive advantages (H2d) | 0.23 (0.27) | 0.87 (0.39) | |

| 0.05 (0.02) | 2.40 (0.02)* | ||

| 0.07 (0.01) | 3.72 (0.00)⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| R2 | 0.57 | ||

Dependent variable: Firm performance's significance is denoted by

We further observe the multi-level moderated model's direct effects. Compared with the random intercepts model, the coefficient of innovation resources drops by 1.09. Thus, we find that innovation resources (β=0.92, p=0.08) still have significantly positive impacts on firm performance. It implies that a 1% increase in innovation resources leads to a 0.92% increase in firm performance. Thus, Hypothesis 1a is supported.

The coefficient of slack resources increases by 0.18. Apart from that, we see that slack resources (β=0.25, p=0.00) have a significantly positive impact on firm performance. An improvement of 1% will lead to around a 0.25% increase in firm performance. Similarly, Hypothesis 1b is supported.

We also note that organizational resources (β=0.24, p=0.02) have significantly positive impacts on firm performance in the multi-level moderated model versus the positive non-significant result from the random intercepts model. The coefficient of organizational resources increases 0.22, implying that a 1% increase leads to a 0.24% increase in firm performance. Accordingly, Hypothesis 1c is supported.

We now turn to discuss the moderation effect of industrial environment factors. This study argues that the relationship between firm-level competitive advantages and firm performance is significantly positively moderated by industry potential. Here, the β coefficients of firm-level competitive advantages that include innovation, organization, and slack are β= 2.24 (p=0.03), β= 0.80 (p=0.00), and β= 0.18 (p=0.00), respectively. Therefore, there is positive moderation effect of industry potential between firm performance and firm resource advantages from these results. Thus, Hypothesis 2a is supported.

This study considers a negative relationship among firm-level competitive advantages with firm performance when they are moderated by industry competitiveness, because an industry environment of intense competition may lead a firm to have fewer heterogonous resources and worse performance. From the results, we find that the β coefficients of innovation resources, organization resources, and slack resources are β = -2.08 (p=0.03), β = -0.13 (p=0.03), and β = -0.15 (p=0.02), respectively. It implies that firm resource advantages have a negatively significant effect on firm performance when they are moderated by industry competitiveness. Thus, Hypothesis 2b is supported.

To understand the moderating effect on firm-level competitive advantages by industry scale, this study reveals that innovation resources and organizational resources are significantly positively moderated by industrial scale. Here, the β coefficients are 0.12 (p=0.00) and β= 0.51 (p=0.07), respectively. However, despite researchers positing the positive relationship between slack resources and firm performance moderated by industry scale, the results indicate a non-significantly negative relation between slack resources and firm performance in the multi-level moderated model, whereby the β coefficient of inventory is -0.35 (p=0.20). Accordingly, Hypothesis 2c is partially supported.

The relationships between organizational resources and slack resources with firm performance are significantly positively moderated by industry dynamics, where the β coefficients are 0.05 (p= 0.02) and 0.07 (p= 0.00), respectively. However, the relationship between innovation resources and firm performance is non-significant. The β coefficient is 0.23 (p=0.39). Thus, Hypothesis 2d is partially supported.

We observe that the coefficient of moderating effect of industry potential is 3.22, the industry competitiveness coefficient is -2.36, the industry scale coefficient is 0.63, and the industry dynamism coefficient is 0.12. Comparing these values, we find that industry potential has the most significant impact on the relationship between firm competitive advantages and performance, aligning with other research findings. The moderating effects of industry scale and dynamism on corporate competitive advantage are relatively weak. Specifically, the moderating effect of industry scale on firm slack resources and the moderating effect of industry dynamism on firm innovation resources are not observed.

Conclusion and discussionConclusionThis research investigates multi-level competitive advantages’ effects on firm performance, using a sample of 769 listed firms in Taiwan. We find that the direct effect of firm-level competitive advantages is significant, and that multi-level variables are sometimes complementary. The relationship between firm-level competitive advantages and firm performance is positively moderated by industry potential, while industrial scale and dynamics have a partly positive moderation effect. Finally, the relationship between firm-level competitive advantages and firm performance is negatively moderated by industrial competitiveness.

Industrial environment factors can help a firm to obtain resources and capabilities. This study thus finds that the relationship between firm-level competitive advantages and firm performance is positively moderated by industry potential. One likely reason is that industry potential can be provided under both market attractiveness and a good survival environment for an enterprise.

In the statistical results, we also show that the moderation effect of industrial scale is partially supported. The reason might be that a large-scale industry leads to a firm tending to keep several slack resources to reduce supply chain risk, rather than adopt an operation strategy of run-down stocks or low-cost strategy. Therefore, each certain scale firm may choose to increase operating costs to maintain abundant slack resources in order to cope with risk. In addition, the moderation effect by industrial dynamics between innovation resources and firm performance is not significant. The reason could be that a firm has homogenization of management, and that each firm's innovation characteristic is similar in the same industry - when there are more industrial dynamics, there are fewer innovation transfers by the firm. Moreover, the moderation effect of industrial competitiveness is negative, implying that the internal competition pressure of industry is formed by a competitive inter-industry environment.

DiscussionsWe adopt the influences of the industry-level variables of industry potential, industry competitiveness, industry scale, and industry dynamics as moderating effects. The first moderating effect is Industry potential. Different industries possess varying levels of potential based on factors such as market scale, technological innovation, blue or red sea development strategy, and competitive landscape (Noponen et al., 1997). There are not only market or technological advantages, but also opportunities and attractiveness for firms. As usual, sunrise industries have more potential for development than sunset industries. Hence, an industry with more potentiality will encourage or even push firms to raise their aspirations and elevate their performance. The literature has proven that a potential industry forms a cluster of innovative infrastructure and knowledge structure to facilitate improving firm performance (Doronina et al., 2016; Mazur et al., 2016). This also corroborates our empirical results.

The second moderating effect is Industry competitiveness. A competitive industry does not necessarily ensure favorable growth prospects for firms. Highly competing industries result in firms’ technology transfer, human capital flow, decreased market share, and competitive advantages that are gradually eroded by homogenous competitors. In other words, the degree of competition among industries strongly correlates with firm performance in that fiercer competition will force each firm to try to improve its performance. Industry competitiveness is a double-edged sword when knowledge and innovation transfer from others (Chaithanapat et al., 2022). This observation also corroborates our empirical results.

The third moderating effect is Industry scale. The industrial scale can be regarded as a cluster that reflects how firms grow and exit. From the life cycle view, the sustainable development of industries is derived from the innovation of technological change. Hence, scale effective expansion implies industries with high attraction and profit margins. In this view, Camisón and Villar-López (2014) suggested that a cluster is a key factor for the core competence of a firm's sustainable development. In particular, a cluster causes an innovation resource concentration of firms in the same industry, which would help set themselves up for performance growth and to avoid closing down. The advantages of co-corporation in the same industry are commonly referred to as economies of scale. For instance, a small-scale industrial cluster offers greater opportunities for a firm through the effect of economies of scale (Skarlis et al., 2012). In turn, a large-scale industrial cluster usually means a dense resource of innovation and information to facilitate firm growth (Nikpour et al., 2017). Although the above observations only corroborate some of our empirical results, future research can explore this phenomenon by collecting a variety of country samples that enlarge the difference between industries and are able to closely observe industry scale.

The fourth moderating effect is Industry dynamics. The dynamic of an industry implies a continuous startup entry that ensures its vitality and resilience. Hence, a dynamic industrial structure brings forth homogeneous pressure and forces some firms that lack innovation capabilities to quit the market. This implies that industrial dynamics influence the stability of firm performance. Zhu et al. (2018) stated that the stability of industrial structure negatively influences firm performance. A stable industry structure may result in a firm lacking innovation motivation in both its product and business models. For instance, some traditional manufacturers hope to finish industry upgrades through high-tech innovation, but almost no one in a traditional industry dares to take the risk of being the first to innovate and change. Saxenian (1990) explored organizational survival as a persistent dynamic industry effect on firm performance. In more detail, over the same industry, a higher survival rate for enterprises indicates lower industrial dynamics, while a lower survival rate for firms indicates higher industrial dynamics. The above prediction is only partially supported by our empirical results. Further research can explore this phenomenon by conducting a longitudinal analysis with panel data.

Theoretical contributionsThis study uses extensive data to explore multi-level competitive advantages related to firm performance so as to capture a complete picture of the outcome. We offer new implications for the existing strategy literature in the manner of multi-level analysis. First, other studies only examined either an internal competitive advantage or an external competitive environment. Our research integrates the multi-level perspective to resolve the problem of analyzing cross-level competitive advantages.

Second, no study has yet to determine the moderating role of industrial competitive advantages and environmental factors in the relationship between a firm's competitive advantage and performance. Our study finds that the moderation effects of industrial environment factors on the relationship between firm competitive advantages and performance are both positive and negative. The negative moderating effect of industrial competitiveness is an important result.

Third, this study adopts hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) to deal with nested data structures. Therefore, we are able to avoid possible methodological problems caused by statistical methods (Dang et al., 2017). We provide more details as follows.

To identify the key strategic factors whereby industry environmental factors and firm resource advantages shape firm performance, our research integrates two different theoretical approaches: SCP and RBT. Considering the complexity of external environmental factors, firms develop opportunities and innovation capabilities with more uncertainty in the future. We extend the argument that these two theoretical approaches are not mutually exclusive in combining different-level factors that create competitive advantages. More specifically, firm resource advantages are complemented by industry potential, scale, and dynamics that shape firm performance. This study reveals that the external competitive environment (as formed by SCP) and firm resource advantages (as formed by RBT) simultaneously provide complementarity between firm competitive advantages and industrial competitive environment to achieve a interaction of multi-level competitive advantages that help shape firm performance.

Our first and most primary contribution is overcoming the insufficiency of only investigating what affects firm competitive advantages and shapes their performance from just either a firm resource perspective or an industry structure view. Early research established that a dynamic, uncertain industrial environment causes firms’ growth to be rich in contingencies (Bourgeois, 1980). Numerous studies on strategy management have investigated firm performance based merely on firms’ internal resources endowment while ignoring integrated industry factors and firm competitive advantages. In fact, competitive advantages not only depend on internal resources and capabilities, but uncertain factors in the industrial environment tend to be more innovative and stimulate firms to surpass competition pressure and take on risk for better performance. Furman et al. (2002) indicated that the rapid development of industrial infrastructure and innovation environment facilitates firms to obtain higher economic rent in developing countries. On this basis, our study further investigates the moderating effect of the external environment of industry to ensure the robustness of our research model.

Second, this study provides evidence that an industry's competitiveness plays a negative moderating role in the relationship between firm resource advantages and performance. This is in line with Wagner and Schaltegger (2003). We extend their argument, whereby external environmental factors erode firm competitive advantages through the moderating role of industry competitiveness. Our finding is consistent with other research on monopoly markets in that first-mover firms enhance entry barrier, while start-ups find it difficult to obtain resources. Thus, we emphasize the importance of developing dynamic capabilities and the benefits from innovation, organization, and slack resources in terms of their effects on performance through the moderating impact of industry potential and scale.

Third, concerning the moderating role of the industry environment, we contribute to the literature concerning the effect of integrating internal firm competitive advantages and external environment conditions on firm performance. Our research gives evidence that industry scale and dynamics are partially moderated between firm resources and performance. Industry scale positively moderates the link between innovation resources and performance and not the links between slack resources and performance. Contrarily, industry dynamics positively moderate the link between slack resources and performance and not the links between innovation resources and performance. This can be explained by the fact that a larger industry scale can transfer more technology, and that a firm within the industry obtains greater innovation resources and capabilities through more R&D investment and more selling or sharing of technologies. Moreover, innovation is not influenced by industry dynamics. One possible reason is that firms are not willing to change their R&D strategy at low levels of industry dynamics, because they may attract more human resources and absorb innovation capabilities at high levels of industry dynamics.

Practical implicationsThe negative impact of industry competitiveness is very pronounced, revealing empirical results that other research has not clearly demonstrated. Traditional SCP views suggest that the structural characteristics of an industry affect firm performance, leading to changes in the conduct of the firm, which in turn can influence the economy of the industry. However, this study finds that although firms can enhance their competitive advantages by improving innovation capabilities and acquiring specific resources, their innovation resources are significantly negatively moderated by industry competitiveness. For managers and investors, this may manifest in the loss of human resources, expiration of patents, and intensification of homogenization challenges. Therefore, overcoming the erosion of innovation capabilities and resources by homogenized competition is a long-term issue for managers.

While multi-level competitive advantages could improve firm performance, industrial competitiveness negatively influences the relationship between a firm's competitive advantages and performance. In fact, an economic or industrial organization has finite resources and scale to absorb a newcomer company. Firm performance is thus bound to decline when facing industrial saturation. When firm performance is influenced by the related characteristics of these multi-level competitive advantages, then one can understand how to properly utilize multi-level competitive advantages to enhance the effectiveness of firm performance. This is our contribution to the competitive advantage literature, further serving as a reference for combinations of multi-level competitive advantages in firm management.

Limitations and future researchOur research has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results, particularly data constraints and limited variables. Our study is based on cross-sectional data, without capturing changes over time. HLM can efficiently integrate different-level data structures through the nature of nested data. However, this multi-level study does not allow us to examine specific changes in the variables over a certain period. Owing to firm performance and competitive advantages that can fluctuate with market conditions, a longitudinal design in future research might provide deeper insights into how industry environmental factors, firm competitive advantages, and performance can be expected to co-evolve.

Our selected sample size also focusing solely on listed firms in Taiwan is another limitation that limits the generalizability of the findings to other regions. Different markets may have distinct industrial environments, competitive intensities, and dynamics that could produce different results. Thus, future research can focus on a wider variety of sectors and firms to increase the theoretical generalizability of the framework.

Our research considers several key factors in multi-level competitive advantages such as those at the higher level, including industry potential, scale, dynamics, and competitiveness, and those at the lower level, including firm innovation, organization, and slack resources. Doing so may not capture all relevant aspects of a firm's internal competitive advantages and the industry's external environment factors. Aside from these variables, future studies may consider the effects of other environmental factors, such as technological transfer, government policies, consumer behavior, and location advantages to integrate firm capabilities, which could shape firm performance to be better or find what results in firm performance turning worse.

Finally, future research could explore the effects of multi-level competitive advantages on firm performance in different markets, regions, and countries. Utilizing multi-level analysis and cross-country comparisons could highlight the role of cultural, economic, foreign direct investment, and regulatory differences in shaping the relationship between market conditions, competitive advantages, and firm performance. Since this study finds a significantly negative moderation effect from industrial competitiveness, future research can explore how specific types of competitiveness, such as technological infrastructure competitiveness, regulatory competitiveness, and geographic competitiveness, impact firm competitive advantages.

CRediT authorship contribution statementYun-Zhong Wang: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Fang-Yi Lo: Writing – original draft, Validation, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Kun-Huang Huarng: Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization.

This research has been supported by Humanities and Social Sciences Research Project of Education Department of Hubei Province (Grant no. 23D035).