Firms’ innovation positively affects their competitiveness and thus their financial performance. To bridge the research gap in the theoretical framework of dynamic capabilities and respond to the call for papers to explore new ways of analyzing innovation in family businesses, this study investigates how entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity influence innovative capacity in family firms. Data from 156 family firms are analyzed using the theoretical framework of dynamic capabilities and structural equation modeling. The results reveal that both entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity influence innovative capacity and that this influence is greater when both capabilities act together than when they act individually. This study confirms that entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity are antecedents of innovative capacity. Moreover, entrepreneurial orientation has a greater influence on innovative capacity than absorptive capacity does.

A major concern of companies in general, and family businesses in particular, is achieving and maintaining a level of competitiveness that enables them to compete in dynamic, hostile, uncertain, and everchanging environments (Stieglitz et al., 2016). Among other factors, a company's competitiveness depends on its ability to develop new products and processes to face and adapt to environmental changes (Caseiro & Coelho, 2019; Helfat et al., 2007; Teece et al., 1997). In particular, innovation helps family firms respond effectively to changes outside the firm (Chrisman et al., 2015; De Massis et al., 2016). Agazu and Kero (2024) reviewed 40 studies published between 2015 and 2023 on the relationship between innovation and competitiveness, concluding that firms’ innovation positively affects their competitiveness and thus their financial performance (Nybakk & Jenssen, 2012). Similarly, Acur et al. (2012), Hughes and Morgan (2007), and Szutowski et al. (2019) all find that innovative capacity positively influences business growth. Given the need to continue exploring innovation's challenges and opportunities (Lee et al., 2010; Thorpe et al., 2005), this study analyzes the innovative capacity of family firms, thereby replying to the calls of Aparicio et al. (2019) and Casado-Belmonte et al. (2021) to advance research on innovation and its determining factors in family firms.

Innovative capacity in family firms can be analyzed from different perspectives using various theoretical frameworks (Calabrò et al., 2019). In this study, we adopt the dynamic capabilities approach (Teece et al., 1997) following Díaz et al. (2006), García-Valderrama et al. (2009), Hernández-Perlines et al. (2019), and Monteiro et al. (2019). This analytical method is based on the premise that companies can build and maintain their competitive advantage by creating and reconfiguring their resources and capabilities in the long term (Damanpour & Wischnevsky, 2006). Few studies have adopted the dynamic capabilities approach to analyze firm-level innovation. Among this scarce literature, De Massis et al. (2016) examined multiple case studies, showing that innovation outcomes must be internalized and reinterpreted through the lens of a firm's capabilities and knowledge. Casprini et al. (2017) analyzed how open innovation in family firms is determined by their internal resources and external knowledge, using a single case study.

In the present study, we define innovative capacity as the result of the continuous development of innovation derived from the creation, transformation, and application of knowledge (Joshi et al., 2015). From a dynamic perspective, this involves the creation of new products and processes (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996) and the introduction and development of innovations (Nakata et al., 2011). However, we go a step further by analyzing the multiple factors that determine innovation in family firms (Aparicio et al., 2019; Calabrò et al., 2019).

The first antecedent of innovative capacity analyzed in this study is entrepreneurial orientation (Rhee et al., 2010; Zeebarree & Siron, 2017). Kammerlander and Ganter (2015) and Kammerlander et al. (2015) claimed that innovation depends on the entrepreneurial behavior of family firms. Moreover, entrepreneurship is crucial to the success of family businesses, affecting their profitability, growth (Casillas & Moreno, 2010; Zahra, 1996; Zahra et al., 2004), and survival (Kellermanns & Eddleston, 2006). Indeed, multiple studies show that entrepreneurial orientation positively impacts firms’ performance (Barroso Martínez et al., 2016; Chirico et al., 2011). Hence, following Cruz and Nordqvist (2012), Hernández-Perlines et al. (2018), Kellermanns et al. (2012), Naldi et al. (2007), and Zahra (2005), we measure entrepreneurship using entrepreneurial orientation.

Entrepreneurial orientation has recently become a focus of research (Covin & Wales, 2012) and has not only experienced significant growth in the management literature (Lomberg et al., 2017), but also established itself as a specific field (Mason et al., 2015) in business management (Basco et al., 2020; Cavusgil & Knight, 2015; Wales et al., 2013). It has been defined as a company's skill to seize new business opportunities (Hernández-Perlines, 2018; Rigtering et al., 2017). According to Miller (1983), a company's entrepreneurial orientation represents its willingness to take risks, promote innovation, and operate proactively. Similarly, according to Russell Merz and Sauber (1995) entrepreneurial orientation is linked to proactive and innovative behaviors. Lumpkin and Dess (1996) added competitive aggressiveness and autonomy to the aforementioned behaviors.

From the literature reviewed above, two approaches for measuring entrepreneurial orientation stand out. The first asserts that the three characteristics that best define entrepreneurial orientation are innovation, proactivity, and risk-taking (Miller, 1983). According to Covin and Slevin (1989)), a company's entrepreneurial orientation depends on its degree of change, innovation, and risk-taking when aggressively competing. This concept of entrepreneurial orientation aligns with a company's ability to develop innovations, take risks, and be pioneers in its strategies (Fairoz et al., 2010). Further, according to Lomberg et al. (2017), the dimensions of innovation, proactivity, and risk-taking define entrepreneurial orientation by capturing the essence of entrepreneurial behavior (Basco et al., 2020).

The second approach defines entrepreneurial orientation as a set of processes, practices, and decision-making activities that lead to the entry of new businesses (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). In addition to innovation, proactivity, and risk-taking (Miller, 1983), this definition considers autonomy and competitive aggressiveness. According to Covin and Wales (2019) and Hernández-Perlines et al. (2021), the fundamental distinction between Miller's (1983) proposal and Lumpkin and Dess’ (1996) approach is that the first considers that entrepreneurial orientation depends on the coexistence of five dimensions, while the second states that they operate independently.

In this study, we follow the first approach. Based on the above framework and research objectives, we analyze the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and innovative capacity through the following research question:

RQ1: Does entrepreneurial orientation influence innovative capacity and, if so, how?

The second antecedent of innovative capacity analyzed in this study is absorptive capacity. Multiple studies have pointed out that innovation is determined by absorptive capacity (Aparicio et al., 2019; Calabrò et al., 2019; Cepeda-Carrión et al., 2012; Kotlar et al., 2020; Wang & Wang, 2012). It is a dynamic capability (Wang & Ahmed, 2007), with several definitions existing in the literature. However, the most relevant definition accepted by most scholars (Volberda et al., 2010) is attributed to Zahra and George (2002), who stated that absorptive capacity is “a set of routines and organizational processes through which companies acquire, assimilate, transform, and exploit knowledge” (p. 186).

Jansen et al. (2005), Lane et al. (2006), and Todorova and Durisin (2007)) analyzed the multidimensional nature of absorptive capacity. Jansen et al. (2005) argued that a company's success depends largely on its ability to recognize, assimilate, and apply new knowledge. Lane et al. (2006) examined the influence of absorptive capacity on innovative performance, financial performance, competitive advantage, and knowledge transfer. According to Garcés-Galdeano et al. (2024), absorptive capacity also plays a key role in enabling learning and innovation. Innovation enables a company to exploit business opportunities (Ireland et al., 2009). Furthermore, it is crucial for business competitiveness (Greve, 2009) and performance (Tsai & Yang, 2014), even affecting a company's survival (Van Gils et al., 2014). Innovation allows companies to create new products and processes and enter new markets (Wang & Ahmed, 2007). It generates value from something new or improved (Carnegie & Butlin, 1993).

In the present study, we adopt Prajogo and Sohal's (2006) definition of innovation, which goes beyond the conventional research and development (R&D)-based approach and focuses on innovation development, allowing us to connect it with absorptive capacity. In this context, understanding that absorptive capacity is the ability to recognize the importance of new opportunities and generate new knowledge (Matthews, 2002), we propose the following research question:

RQ2: Does absorptive capacity influence innovative capacity and, if so, how?

This study specifically targets family businesses since they are the most represented business model in the world (Gedajlovic et al., 2012; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007; Hernández-Perlines & Ribeiro-Soriano, 2023). According to the 2023 Global Family Business Index developed by Ernst and Young and the University of St. Gallen in Switzerland, family businesses are the backbone of most economies and represent between 80 % and 90 % of global businesses (Family Business Index, 2023).

Our study contributes to the literature on family firm innovation, entrepreneurship management, absorptive capacity, and business management by confirming the factors that influence innovative capacity in family firms as well as revealing the factor that has the higher influence on family firms’ innovative capacity. Additionally, by using the dynamic capabilities approach and partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to analyze the data, the research contributes to the family business literature, since these methods are rarely used to analyze the relationships among entrepreneurial orientation, absorptive capacity and innovative capacity.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses developmentInnovative capacity is relevant for a firm's competitiveness and performance (Agazu & Kero, 2024; Ortiz-Villajos & Sotoca, 2018). Many authors have highlighted the positive relationship between innovation and competitiveness, including, most recently, Agazu and Kero's (2024) systematic literature review of 40 studies published between 2015 and 2023 in Scopus, Web of Science (WOS), PubMed, and Taylor and Francis. Innovation is also a relevant research topic in the literature on family businesses (Aparicio et al., 2019; Calabrò et al., 2019; Casado-Belmonte et al., 2021; Migliori et al., 2020; Strobl et al., 2020). However, the findings on innovation in general and in family businesses specifically are contradictory, necessitating further research to delve deeper into the topic.

Aparicio et al. (2019) conducted a bibliometric study on innovation in family firms by analyzing 207 studies published between 1994 and 2017 in WOS. They corroborated the academic interest on innovation in family businesses, noting a substantial increase in the number of publications on this topic in WOS journals. They classified these papers into three main categories. The first includes papers identifying the internal characteristics that affect innovative behavior by family firms. They highlighted significant heterogeneity among family firms because of their individualities, including family culture, non-financial objectives, internal relationships, entrepreneurship, and governance. Consequently, they analyzed the effects of entrepreneurial orientation on innovation in family businesses. The second category includes studies on external factors as determinants of innovation in family businesses. The third category includes advanced research on innovation in family businesses and their management and innovation improvement.

Calabrò et al. (2019) conducted a systematic review of the literature on innovation in family businesses in 118 peer-reviewed journal articles published between 1961 and 2017. They found significant heterogeneity in contributions on innovation in family firms, dividing the contributions into three main groups: theoretical, qualitative empirical, and quantitative empirical. In the first group, most of the studies have used a multi-criteria theoretical framework, with few using dynamic capabilities to study innovation in family firms. The second group includes research based on the case method (single or multiple cases) to analyze innovation. Within this group, De Massis et al. (2016), using a multiple-case methodology, described innovation through tradition, which is affected by the capabilities needed to internalize and reinterpret past knowledge. The third group includes quantitative studies, which have analyzed not only the direct effect of family variables on innovation, but also the influence of innovation on family business performance, including the moderating roles of family variables.

Another systematic review of the literature on innovation in family businesses was carried out by Casado-Belmonte et al. (2021). These authors reviewed 975 papers published between 1987 and 2019 in the WOS and Scopus databases. They grouped the papers into four theoretical frameworks and five thematic clusters, encouraging further research on family firm innovation through an integrative framework that improves the understanding of heterogeneous innovation behavior in family firms. According to them, entrepreneurship and absorptive capacity are the key factors for innovation in family firms.

Finally, Hu and Hughes (2020) conducted a systematic literature review on radical innovation in family firms based on 51 articles published between 2003 and 2018 in high-impact journals. These 51 papers were classified into four groups according to the authors’ theoretical approach: the resource-based view approach and its capabilities extension, agency and stewardship theory, behavioral agency and socioemotional wealth, and the capability and willingness paradox. The authors revealed that only one article has used entrepreneurial orientation as a basis for explaining radical innovation. Similarly, Craig et al. (2014) analyzed the radical innovation of 532 firms in Finland, concluding that risk-taking does not affect innovation outcomes and revealing that only one study, Huang et al. (2015), which focused on 165 Taiwanese firms, has specified that absorptive capacity facilitates innovation by moderating the relationship between R&D budget allocation and innovation.

Innovative capacityInnovation is a recurring topic in business management research. It covers aspects such as the development of new products or services, production methods, organizational models, market identification, and supply chain management (Schumpeter, 1934). According to Miller and Friesen (1983), innovation has four dimensions: a) new product or service innovation, b) production method or service delivery innovation, c) risk-taking by executive team members, and d) the search for unusual and new solutions. Capón et al. (1992) focused on organizational innovation, defining three dimensions: a) market-wide innovative capacity, b) pioneering strategic trends, and c) technological sophistication. Companies can improve their results through innovation in new or improved products and processes to meet the needs of their current and potential customers (Orlay, 1993). According to Prajogo and Sohal (2006), changes in products or services may come from different innovation processes based on the generation of new ideas.

The innovation process involves product and process innovation, which both affect companies’ competitiveness and are essential for economic growth (Camison & Villar-López, 2010). This bidimensional concept of innovation provides a broader perspective than the traditional R&D and innovation definition, and it is the most widely accepted approach to understand innovation (Camison & Villar-López, 2010; Miller & Friesen, 1983; Prajogo & Sohal, 2006). The relevance of innovation lies in its regular and continuous implementation (Hjalager, 2010), which enables companies to reach new markets (Wang & Ahmed, 2004).

Innovative capacity allows certain behaviors to emerge in a company to implement new products and markets, forming the basis of the competitive advantage that the company can gain from the relationship among its resources, capabilities, and the environment (Wang & Ahmed, 2007). This research focuses on the innovation definition based on the generation of new products and processes (Prajogo & Sohal, 2006; Schumpeter, 1934).

De Massis et al. (2013), Duran et al., (2016), and Miller and Le Breton-Miller (2005) studied innovation in family businesses as an indicator of firm success and survival (Calabrò et al., 2019; Eddleston et al., 2008; Nordqvist et al., 2009). However, despite the significant increase in studies analyzing innovation in family businesses, how innovation acts over successive generations remains unclear (Calabrò et al., 2019; Chrisman et al., 2015;). De Massis et al. (2014) and Chrisman et al. (2015) attributed this to the paradox of capacity and willingness. Innovation in family businesses is often more productive than that in non-family businesses (De Massis et al., 2013). Family firms have resources and capabilities that allow them to be competitive and maintain their competitiveness over time (Sharma & Salvato, 2011). This advantage depends on their (dynamic) capability to adapt, include, and reconfigure acquired knowledge (Zellweger & Sieger, 2012). The theoretical framework of dynamic capabilities underpins our research (Ingram & Kraśnicka, 2023; Makadok, 2001; Prahalad & Hamel, 1990; Teece et al., 1997), as such capabilities enable companies to adapt to everchanging environmental conditions. Moreover, certain family business characteristics favor innovation (Bammens et al., 2015; Duran et al., 2016). Family businesses have recently begun to apply open innovation through collaborative strategies (Lambrechts et al., 2017). Kotlar et al. (2013) analyzed the factors that facilitate or hinder open innovation in family businesses.

Entrepreneurial orientationEntrepreneurial orientation has recently become one of the most important topics in the business literature (Covin & Miller, 2014; Covin & Slevin, 1991; Engelen et al., 2015; Kropp et al., 2006; Rauch et al., 2009). Entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial orientation are critical to the survival and growth of family firms (Acs & Armington, 2004; Classen et al., 2012), which offer a unique context of resources and capabilities for entrepreneurial orientation (Casillas et al., 2010). Moreover, entrepreneurial orientation is a key factor behind innovation in family businesses (Aparicio et al., 2019; Calabrò et al., 2019; Casado-Belmonte et al., 2021; Hu & Hughes, 2020). We examine entrepreneurial orientation because although previous studies have pointed out that entrepreneurial orientation can explain innovation in family firms, recent research has recommended further studies (Aparicio et al., 2019; Calabrò et al., 2019; Casado-Belmonte et al., 2021; Hu & Hughes, 2020).

Entrepreneurial orientation has undergone multiple reformulations since its original conception, evolving into a dynamic concept. Miller (1983) was the first to discuss entrepreneurial orientation, characterizing it as a firm's behavior marked by innovation, proactivity, and risk-taking. Later, considering this definition, some authors stated that entrepreneurial orientation depends on the degree to which change, innovation, decision-making, and aggressive competition are stimulated (George & Marino, 2011; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2005). Engelen et al. (2015) defined entrepreneurial orientation as a company's ability to carry out innovation-related activities, take risks, and pioneer new actions. In other words, adopting an entrepreneurial orientation can help create new market offerings, take risks to test new products/services and markets, and be more proactive than competitors when exploiting new opportunities (Covin & Slevin, 1991; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Miller, 1983; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2005).

The dimensionality of entrepreneurial orientation and interdependence between its dimensions have been fiercely debated (Covin et al., 2006; Knight, 2000; Kreiser et al., 2002; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). As noted earlier, entrepreneurial orientation in our study consists of three dimensions: innovation, proactivity, and risk-taking. Innovation is characterized by a tendency to support new ideas, experiment, and use creative processes (Chandra et al., 2009; Kropp et al., 2006; Miller & Friesen, 1983). Proactivity refers to pioneers seeking advantages by anticipating future market desires and needs to capitalize on emerging business opportunities (Covin & Slevin, 1989; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996) and introduce new products and services before competitors (Rauch et al., 2009). Risk-taking involves implementing strategies that require significant resources without a high assurance of success (Kraus et al., 2012; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). Entrepreneurial orientation is considered to be a second-order composite mode (for more information, see Covin & Wales, 2012; Hansen et al., 2011; Hernández-Perlines, 2016; Rauch et al., 2009); in other words, it captures business behavior crucial for its relationship with business performance. The theoretical argument underpinning this statement is that companies benefit from innovation, proactivity, and risk-taking (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996).

Previous studies have confirmed the positive relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance (Barringer & Bluedorn, 1999; Covin & Slevin, 1989; Davis et al., 2010; Frank et al., 2010; Hernández-Perlines et al., 2016; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Miller, 1983; Wiklund, 1999; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2005; Zahra, 1991; Zahra & Covin, 1995). This relationship is considered to be independent of company characteristics and national context (Ibarra-Cisneros et al., 2021; Rauch et al., 2009; Saeed et al., 2014), making entrepreneurial orientation a valuable predictor of business success (Hernández-Perlines & Ibarra Cisneros, 2017; Kraus et al., 2012) and confirming the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and business competitiveness (Hughes et al., 2018; Yin et al., 2021). This relationship allows the redesigning of processes to explore new growth paths (Alam et al., 2023). Additionally, previous studies have linked entrepreneurial orientation to innovative capacity based on the desire to test creative ideas (Gupta & Batra, 2016; Real et al., 2014; Shan et al., 2016).

Based on the above, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1

Entrepreneurial orientation positively influences the innovative capacity of family businesses.

Absorptive capacityIn this study, absorptive capacity is considered as the ability to explore, assimilate, transfer, and apply new knowledge (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Zahra & George, 2002). Absorptive capacity has a positive effect on a company's innovative behavior (Aljanabi et al., 2014; Cepeda-Carrion et al., 2012; Garcés-Galdeano et al., 2024; González-Campo & Ayala, 2014). It enables companies to recognize, assimilate, and apply new knowledge to compete in the market (Jansen et al., 2005). Cohen and Levinthal (1990) were the first to define absorptive capacity, stating that it is a company's ability to identify, assimilate, and exploit new knowledge. This is intangible and crucial for value creation. The concept has evolved over time, with the most relevant definition attributed to Zahra and George (2002). From this definition, an abundant literature on absorptive capacity has emerged (Volberda et al., 2010), with some studies addressing its multidimensional nature (Jansen et al., 2005; Lane et al., 2006; Todorova & Durisin, 2007) and others analyzing its antecedents (Andersen & Foss, 2005; Argote & Ingram, 2000; Dijksterhuis et al., 1999; Kogut & Zander, 1992; Lane & Lubatkin, 1998; Lane et al., 2001; Lenox & King, 2004; Lyles & Salk, 2007; Van den Bosch et al., 1999). Some studies have also analyzed the influence of absorptive capacity on innovative performance, financial performance, competitive advantage, and knowledge transfer (Lane et al., 2006).

Additionally, some have analyzed its mediating role. For example, Aljanabi et al. (2014) studied absorptive capacity's mediating role in the relationship between organizational support factors and technological innovation. Leal-Rodríguez et al. (2014) focused on innovation outcomes. Sáenz et al. (2014) and Adisa and Rose (2013) analyzed the mediating effect of absorptive capacity on buyer–supplier relationships and knowledge transfer, respectively, while Liu et al. (2013) and WuYang et al. (2010) examined this effect on the relationship between information technology capabilities and firm performance and technology management capacity and new product development performance, respectively. Other authors have highlighted the moderating role of absorptive capacity. For example, Hayton and Zahra (2005) confirmed that absorptive capacity moderates business growth through collaboration or acquisitions and outcomes measured by revenue volume and new product/process development. Additionally, Zahra & Hayton (2008) affirmed that absorptive capacity positively moderates the relationship between international activities and business performance.

However, studies analyzing absorptive capacity in family businesses are scarce (Andersen, 2015; De Masis et al., 2013; Garcés-Galdeano et al., 2024; Hernández-Perlines & Ibarra Cisneros, 2017). Among the scarce literature, Andersen (2015) stated that absorptive capacity behaves differently depending on the type of family business analyzed. Ferreira and Ferreira (2017) claimed that absorptive capacity largely determines the innovation performance of family businesses. Furthermore, Volberda et al. (2010) revealed that the ownership of a family business is a key determinant of its absorptive capacity, while Kotlar et al. (2020) analyzed how certain internal contingency factors related to emotional attachment and power concentration facilitate or hinder absorptive capacity. According to Gómez-Mejía et al. (2007), socioemotional wealth sheds light on absorptive capacity in family businesses. Ali and Park (2016) analyzed the relationship between two types of absorptive capacities (potential and realized), innovative culture, and organizational innovation.

Thus, based on the above, we propose the second hypothesis as follows:

H2

Absorptive capacity positively influences the innovative capacity of family businesses.

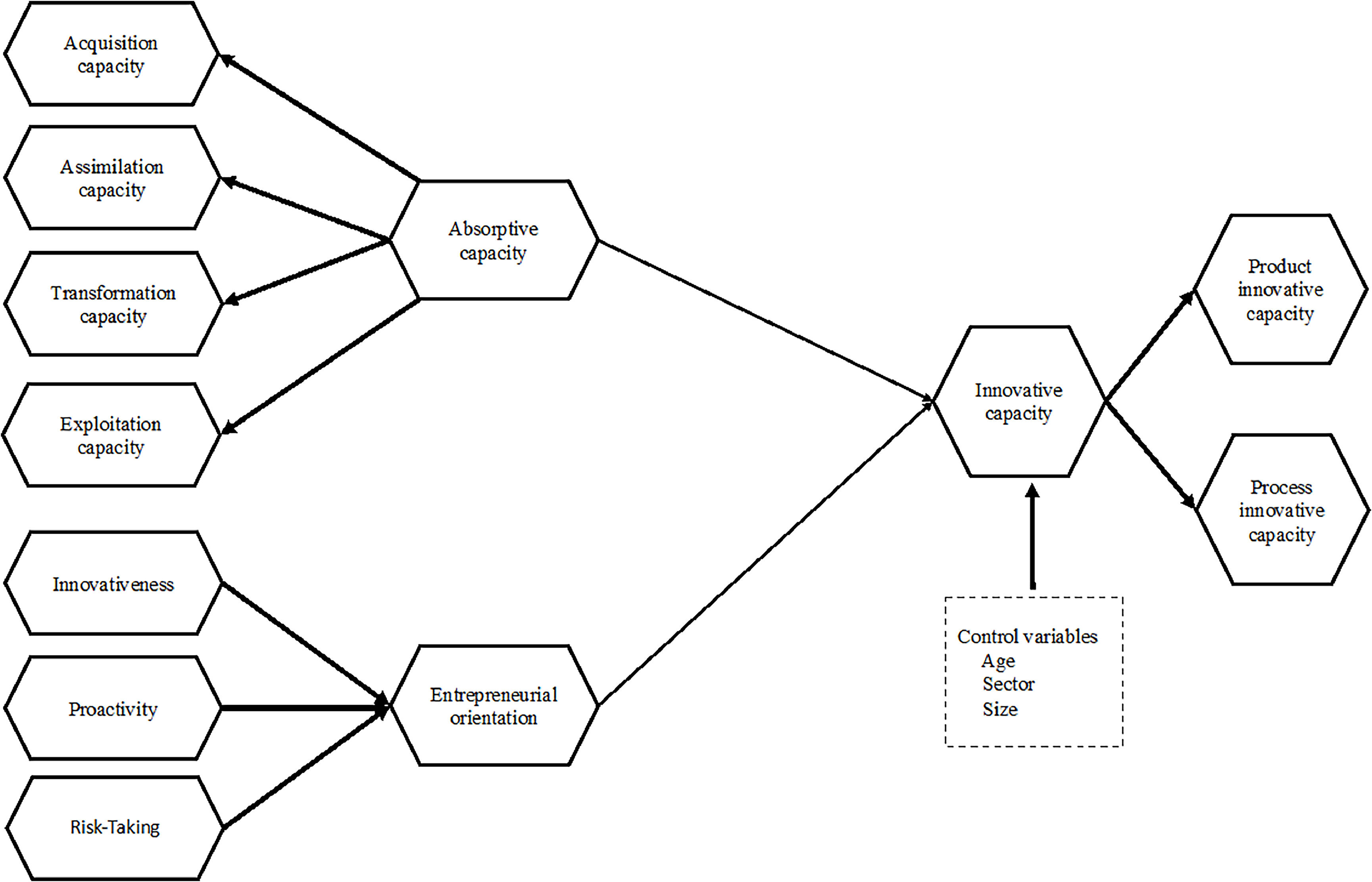

Fig. 1 presents the proposed research model.

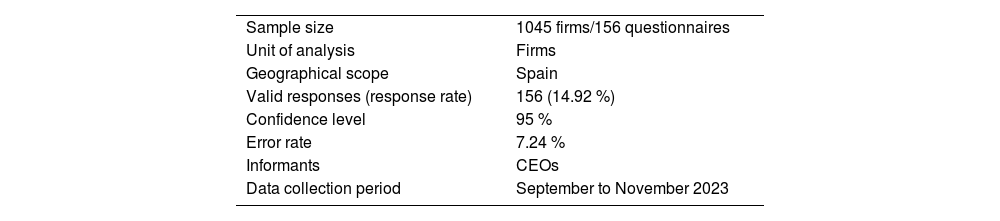

MethodologyData collectionTo collect the data for this study, we used a questionnaire design. Between September and November 2023, questionnaires were emailed through the LimeSurvey platform from the user service center of the University of Castilla-La Mancha to the chief executive officers (CEOs) of 1045 family businesses associated with the Institute of Family Business in Spain. In response to the survey, 156 valid questionnaires were received (response rate: 15 %), from which we collated the required data. Table 1 shows the sample construction.

Sample construction.

| Sample size | 1045 firms/156 questionnaires |

| Unit of analysis | Firms |

| Geographical scope | Spain |

| Valid responses (response rate) | 156 (14.92 %) |

| Confidence level | 95 % |

| Error rate | 7.24 % |

| Informants | CEOs |

| Data collection period | September to November 2023 |

Source: Compiled by the author.

As shown in Table 2, of the 156 family businesses, 67.30 % are older than 25 years, 76.27 % employ fewer than 249 workers (i.e., they are defined as small and medium-sized enterprises), 41.03 % operate in the service sector, and 26.28 % are first-generation family firms. Regarding their CEOs, 46.15 % do not have a university degree, 55.76 % are men, and 61.53 % are family members. Furthermore, 54.49 % of the firms have external directors on their board of directors.

Sample information.

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Firm age (years) | < 25 | 51 | 35.70 |

| > 25 | 105 | 67.30 | |

| Firm employees | 10–49 | 64 | 41.02 |

| 50–249 | 55 | 35.25 | |

| > 250 | 37 | 23.73 | |

| Firm sector | Primary | 34 | 21.80 |

| Industrial | 58 | 37.17 | |

| Services | 64 | 41.03 | |

| Generation | 1st | 41 | 26.28 |

| 2nd | 70 | 44.87 | |

| 3rd or more | 45 | 28.85 | |

| CEO education level | No university | 72 | 46.15 |

| University | 84 | 53.85 | |

| CEO gender | Male | 87 | 55.76 |

| Female | 69 | 44.24 | |

| Family CEO | Yes | 96 | 61.53 |

| No | 60 | 38.47 | |

| External directors on the board | Yes | 85 | 54.49 |

| No | 71 | 45.51 |

Source: Compiled by the author.

The statistical power of the sample used in this study was 0.995. It was calculated using Cohen's (1992) retrospective power analysis and obtained using the G*Power 3.1.9.6 program (Faul et al., 2009). The obtained value allows us to state that the sample used in this study has adequate statistical power, as it exceeds the threshold of 0.80 set by Cohen (1992).

Measurement of the variablesIn this study, innovative capacity was the dependent variable, while entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity were used as independent variables. All three variables were measured using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Innovative capacity was measured using the scale proposed by Prajogo and Sohal (2006), which considers both product innovative capacity (five items) and process innovative capacity (four items). As this scale considers competitors, it reduces subjective response bias (Kraft, 1990). Entrepreneurial orientation was measured using nine items assessing innovation, proactivity, and risk-taking. The items were taken from the scale proposed by Miller (1983) and modified by Covin and Slevin (1989)) and Covin and Miller (2014). Absorptive capacity was averaged from a scale of a multidimensional nature (Jansen et al., 2005; Lane et al., 2006; Todorova & Durisin, 2007), which includes four dimensions: acquisition (three items), assimilation (four items), transformation (four items), and exploitation (three items). In addition, following J.J. Chrisman et al. (2015), we used three control variables: firm size, measured by the number of employees; firm age, measured by the number of years since foundation; and firm sector, considering the primary, industrial, and service sectors.

ResultsThe data were analyzed using the PLS-SEM technique (Ringle et al., 2024). PLS-SEM is increasing used in management, strategy, marketing (Sattler et al., 2010), and family business research (Vallejo, 2009). Several studies have highlighted the usefulness of this model as a research tool in the field of family business (Sarstedt et al., 2014). Further, Rigdon et al. (2017) recommended using PLS-SEM over any other method of data analysis. Specifically, PLS-SEM was appropriate for this study for the following five main reasons:

- ·

This method assesses the causal relationships between the analyzed variables (Astrachan et al., 2014; Jöreskog & Wold, 1982).

- ·

It allows for the inclusion of latent variables with reflective and formative indicators (Henseler et al., 2009), that is, type A or B variables, as in our study.

- ·

It does not set strict assumptions about the normality of the data (Chin, 1998) and can be used with small samples (Henseler et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2011; Reinartz et al., 2009).

- ·

It can analyze structural models with multi-item constructs and direct and indirect relationships (Vallejo, 2009).

- ·

It can analyze complex relationships in models based on second-order constructs (Hair et al., 2019).

SmartPLS v. 4.1.0.8 software was used to analyze the data (Ringle et al., 2024). Following the recommendations of Barclay et al. (1995) and Hair et al. (2017), the measurement model was first evaluated, followed by the structural model.

Evaluation of the measurement modelThe entrepreneurial orientation, absorptive capacity, and innovative capacity variables were modeled based on Sarstedt et al.’s (2016) recommendations:

- ·

Entrepreneurial orientation was operationalized as a second-order multidimensional type “b” composite, with three dimensions considered as first-order type “a” composites, including innovation, proactivity, and risk-taking, in line with Covin and Wales (2012), Hansen et al. (2011), Hernández-Perlines (2018), and Rauch et al. (2009).

- ·

Absorptive capacity was a second-order type “a” composite, with four dimensions operationalized as first-order type “a” composites (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Hernández-Perlines et al., 2016; Lane et al., 2006), using the scale proposed by Flatten et al. (2011). We operationalized absorptive capacity in this way because we assumed that all four dimensions must be present for the firm to have true absorptive capacity even though each dimension has different facets.

- ·

Innovative capacity was operationalized as a second-order type “a” composite, with two dimensions considered as first-order type “a” composites. Again, we operationalized innovative capacity in this way because we assumed that both dimensions must be present for the firm to have true innovative capacity even though each dimension comprises different facets.

- ·

The control variables were managed as a second-order type “a” composite, with three dimensions considered as first-order type “a” composites.

The reliability of the variables was verified and convergent and discriminant validity were assessed following Roldán and Sánchez-Franco's (2012) recommendations using the following indicators (Barclay et al., 1995; Hair et al., 2017; Roldán & Sánchez-Franco, 2012). As shown in Tables 3.a, 3.b, 3.c, and 4, the dimensions have values of loadings, composite reliability,1 Cronbach's alpha,2 Rho a,3 average variance extracted (AVE) ,4 and the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT)5 within the thresholds considered as adequate. Therefore, we confirmed that the different variables used are correct and the measurement model has adequate levels of reliability and convergent and discriminant validity.

Entrepreneurial orientation: item loadings, path coefficient composite reliability, Cronbach's alpha, and Rho a.

| β | Composite reliability | Cronbach's alpha | AVE | Rho a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation | Innov1 | 0.8377 | |||||

| Innov2 | 0.8454 | 0.5143 | 0.8788 | 0.7931 | 0.7931 | 0.7653 | |

| Innov3 | 0.8400 | ||||||

| Proactivity | Proact1 | 0.7709 | |||||

| Proact2 | 0.8342 | 0.4158 | 0.6355 | 0.7348 | 0.6656 | 0.6924 | |

| Proact3 | 0.7783 | ||||||

| Risk-taking | Risk-T1 | 0.8119 | |||||

| Risk-T2 | 0.8231 | 0.2836 | 0.7867 | 0.6083 | 0.5572 | 0.6579 | |

| Risk-T3 | 0.7786 | ||||||

Source: Compiled by the author.

Innovative capacity: item loadings, path coefficient composite reliability, Cronbach's alpha, and Rho a.

| β | Composite reliability | Cronbach's alpha | AVE | Rho a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product innovative capacity | Prodinncap1 | 0.8851 | |||||

| Prodinncap2 | 0.8878 | ||||||

| Prodinncap3 | 0.9248 | 0.5166 | 0.9484 | 0.9217 | 0.7864 | 0.9333 | |

| Prodinncap4 | 0.8893 | ||||||

| Prodinncap5 | 0.8342 | ||||||

| Process innovative capacity | Procinncap1 | 0.8508 | |||||

| Procinncap2 | 0.9136 | 0.5177 | 0.9488 | 0.9279 | 0.8227 | 0.9299 | |

| Procinncap3 | 0.9093 | ||||||

| Procinncap4 | 0.9013 | ||||||

Source: Compiled by the author.

Absorptive capacity: item loadings, path coefficient composite reliability, Cronbach's alpha, and Rho a.

| β | Composite reliability | Cronbach's alpha | AVE | Rho a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition capacity | Acqcap1 | 0.8696 | |||||

| Acqcap2 | 0.9025 | 0.3027 | 0.9239 | 0.8756 | 0.8021 | 0.8809 | |

| Acqcap3 | 0.8646 | ||||||

| Assimilation capacity | Assimcap1 | 0.8543 | |||||

| Assimcap2 | 0.9008 | 0.2888 | 0.9139 | 0.8744 | 0.7266 | 0.8871 | |

| Assimcap3 | 0.8315 | ||||||

| Assimcap4 | 0.8207 | ||||||

| Transformation capacity | Transcap1 | 0.9001 | |||||

| Transcap2 | 0.9132 | 0.2657 | 0.9250 | 0.9070 | 0.8414 | 0.9088 | |

| Transcap3 | 0.9241 | ||||||

| Transcap4 | 0.9002 | ||||||

| Exploitation capacity | Explcap2 | 0.7471 | |||||

| Explcap3 | 0.8751 | 0.3240 | 0.8627 | 0.7592 | 0.6777 | 0.7634 | |

| Explcap4 | 0.8421 | ||||||

Source: Compiled by the author.

Correlation matrix, composite reliability, convergent and discriminant validity, HTMT ratio, and descriptive statistics.

| Construct | AVE | Composite reliability | Entrepreneurial orientation | Absorptive capacity | Innovative capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial orientation | 0.649 | 0.845 | |||

| Absorptive capacity | 0.711 | 0.907 | 0.659 | ||

| Innovative capacity | 0.924 | 0.924 | 0.734 | 0.629 | |

| HTMT ratio | |||||

| Entrepreneurial orientation | |||||

| Absorptive capacity | 0.815 | ||||

| Innovative capacity | 0.810 | 0.695 | |||

| Cronbach's alpha | 0.723 | 0.864 | 0.918 | ||

| Rho a | 0.772 | 0.907 | 0.933 | ||

| Mean | 4.585 | 5.266 | 4.244 | ||

| SD | 2.102 | 1.750 | 1.786 | ||

Note: The mean and standard deviation values of each second-order composite were calculated based on the mean values of the different first-order composites that compose them.

(*) Diagonal values have been obtained from the square root of the AVE of each composite.

Source: Compiled by the author.

Furthermore, to complete the discriminant validity verification, we calculated the HTMT inference using bootstrapping (5000 subsamples). Discriminant validity exists when the resulting interval contains values below 1. Table 5 shows that our data meet this requirement.

HTMT inference.

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | 5 % | 95 % | Sample Mean (M) | Bias | 5 % | 95 % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial orientation ⇒ Innovative capacity | 0.5648 | 0.5651 | 0.4410 | 0.6749 | 0.5651 | 0.0007 | 0.3780 | 0.4741 |

| Absorptive capacity ⇒ Innovative capacity | 0.2525 | 0.2510 | 0.1204 | 0.3805 | 0.2510 | −0.0015 | 0.1245 | 0.3836 |

Source: Compiled by the author.

Once the convergent and discriminant validity of the measurement model have been assured, we can test the relationships among the variables in the structural model. The structural model was first analyzed by considering the influence of each antecedent variable separately, that is, the influence of entrepreneurial orientation on innovative capacity and the influence of absorptive capacity on innovative capacity. Entrepreneurial orientation has a positive and significant influence on innovative capacity since the path coefficient is 0.729, which exceeds the minimum threshold of 0.2 proposed by Chin (1998)), and t is 17.2352 (based on a one-tailed t[4.999] and p < 0.0000) (see Table 6 and Fig. 2). Entrepreneurial orientation alone explains 54.2 % of the variance in innovative capacity (see Fig. 2). For its part, absorptive capacity also positively influences innovative capacity, with a path coefficient of 0.398. Moreover, this influence is significant, having a t-value of 10.4564 (based on a one-tailed t[4.999] and p < 0.0000; see Table 6). Moreover, absorptive capacity explains 39.8 % of the variance in innovative capacity (see Fig. 2). These results allow us to confirm that entrepreneurial orientation has a great influence on innovative capacity and can explain the variance in innovative capacity more than absorptive capacity can.

Structural model.

| Model | R2 | ß | t- value | p- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial orientation ⇒ Innovative capacity | 0.542 | 0.729 | 17.2352 | 0.0000 |

| Absorptive capacity ⇒ Innovative capacity | 0.398 | 0.624 | 10.4564 | 0.0000 |

| Entrepreneurial orientation ⇒ Absorptive capacity | 0.436 | 0.660 | 12.2023 | 0.0000 |

| Entrepreneurial orientation ⇒ Innovative capacity | 0.564 | 7.9053 | 0.0000 | |

| Absorptive capacity ⇒ Innovative capacity | 0.577 | 0.452 | 3.210 | 0.0000 |

Source: Compiled by the author.

The joint effect of both entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity was also analyzed. This analysis shows that entrepreneurial orientation has a greater influence on innovative capacity than absorptive capacity does, with a higher path coefficient of 0.564 compared with 0.452 for absorptive capacity. In both cases, they are significant: the path coefficient of entrepreneurial orientation has a t-value of 7.9053 (based on a one-tailed t[4.999] and p < 0.0000), while the t-value of the path coefficient of absorptive capacity is 3.2100 (based on a one-tailed t[4.999] and p < 0.0000)). Together, entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity explain 57.7 % of the variance in innovative capacity (see Fig. 2 and Table 6).

Finally, entrepreneurial orientation has a positive and significant influence on absorptive capacity since the path coefficient is 0.6603 and the t value is 12.2030 (based on a one-tailed t[4.999] and p < 0.0000) (see Fig. 2).

None of the control variables have a relevant (path coefficients are <0.2) or significant (their values are less than the recommended value, p < 0.001) influence (see Table 7 and Fig. 2).

To complete the analysis of the structural model, we conducted a goodness-of-fit test using the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) method proposed by Hu and Bentler (1998) and Henseler et al. (2015). We obtained an SRMR value of 0.063, which is lower than the threshold value of 0.08 (Henseler et al., 2015).

DiscussionThis study provides valuable insights into the relationships among entrepreneurial orientation, absorptive capacity, and innovative capacity in family firms. The findings confirm that both entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity are significant antecedents of innovative capacity. Moreover, the combined effect of these two dynamic capabilities is more substantial than their individual impacts, highlighting the importance of their interaction. These results align with the dynamic capabilities framework, which emphasizes that a firm's ability to adapt, reconfigure, and innovate in response to environmental changes is crucial to maintaining a competitive advantage (Helfat et al., 2007; Teece et al., 1997).

The role of entrepreneurial orientationEntrepreneurial orientation, which encompasses risk-taking, innovation, and proactivity, plays a crucial role in driving innovative capacity. The findings demonstrate that entrepreneurial orientation has a stronger influence on innovative capacity than absorptive capacity does, confirming that firms with high entrepreneurial orientation are better equipped to innovate. These firms are more likely to engage in creative risk-taking, anticipate market trends, and proactively seek out new opportunities (Covin & Wales, 2012; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). This is particularly relevant for family firms, as they may be hesitant to embrace risk because of concerns about preserving the family's wealth and legacy (Chrisman et al., 2015; Naldi et al., 2007). However, the positive correlation between entrepreneurial orientation and innovative capacity observed in this study suggests that family firms with strong entrepreneurial orientation can overcome such challenges, leading to greater innovation and competitive advantage.

One of the key findings in this research is that entrepreneurial orientation significantly enhances innovative capacity when it is considered both as an independent factor and in conjunction with absorptive capacity. This suggests that entrepreneurial orientation acts as a foundation upon which absorptive capacity can be better utilized. In practical terms, family businesses that actively foster an entrepreneurial mindset within their leadership and organizational culture are more likely to benefit from external knowledge sources, integrating them effectively into their innovation processes. This supports previous studies that highlight the importance of entrepreneurial behavior in family firms as a driving force for sustained innovation and long-term growth (Miller, 1983; Rhee et al., 2010; Zahra & Covin, 1995).

The impact of absorptive capacityAbsorptive capacity, defined as the ability to acquire, assimilate, transform, and exploit external knowledge (Zahra & George, 2002), also significantly contributes to a firm's innovative capacity. Our results reveal that while absorptive capacity is a strong determinant of innovation, its effect is somewhat overshadowed by entrepreneurial orientation. Nonetheless, firms with high absorptive capacity can better recognize valuable external information, adapt it to their internal context, and apply it to innovative efforts. This capacity is particularly important in today's global and dynamic business environment in which the rapid pace of technological advancement necessitates continuous learning and adaptation.

The synergy between entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity found in this study highlights the importance of these two capabilities working together. Absorptive capacity, while essential for identifying and utilizing external knowledge, seems to require a proactive and risk-tolerant culture—characteristics of entrepreneurial orientation—to be fully effective. In family firms, where traditions and established routines might inhibit the assimilation of external knowledge, entrepreneurial orientation can act as a catalyst, enabling firms to overcome inertia and engage more actively in innovative activities (Chrisman et al., 2015; De Massis et al., 2016).

Furthermore, the study's findings suggest that firms with a greater capacity to absorb external knowledge may be better positioned to innovate in terms of not only product development but also process innovation. Process innovation, often overlooked in favor of product innovation, plays a crucial role in enhancing operational efficiency and long-term competitiveness. As firms acquire and integrate external knowledge, they can refine their internal processes, leading to more efficient and effective innovation cycles (Jansen et al., 2005; Lane et al., 2006). This underscores the importance of developing absorptive capacity in family firms, particularly in industries in which process innovation can be a key differentiator.

The interaction of entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacityThe combined analysis of entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity reveals that when both capabilities are present, family firms experience greater innovative capacity than when these capabilities operate independently. This finding suggests a complementary relationship between the two, where entrepreneurial orientation enhances the firm's ability to exploit the knowledge acquired through absorptive capacity. This interaction aligns with the dynamic capabilities perspective, which argues that firms capable of reconfiguring their resources and capabilities in response to changing environments are more likely to sustain competitive advantage (Teece et al., 1997; Barney, 2001).). The results of this study reinforce this view, demonstrating that firms with both high entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity can better navigate complex and volatile business environments.

Family businesses often face unique challenges related to preserving socioemotional wealth, which may limit their willingness to take risks or engage with external knowledge sources (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). However, the positive relationships among entrepreneurial orientation, absorptive capacity, and innovative capacity observed in this study indicate that when family firms embrace an entrepreneurial mindset, they can overcome these challenges. In doing so, they not only enhance their internal innovation processes but also better leverage external opportunities for knowledge and collaboration, which are crucial in today's interconnected global economy.

ConclusionsThis study focuses on the innovative capacity of family businesses as a key aspect of their competitiveness. Authors such as Agazu and Kero (2024) state that innovation is a critical factor in firms’ competitiveness. This research responds to the call by Aparicio et al. (2019) and Casado-Belmonte et al. (2021) to further explore the factors that determine product and process innovation. From the dynamic capabilities perspective, it is argued that competitive advantage is created and maintained by allocating and reconfiguring resources and capabilities in the long term (Damanpour & Wischnevsky, 2006). Further, this research focuses on family firms because they are the most widespread type of business structure worldwide (Hernández-Perlines & Ribeiro-Soriano, 2023), representing between 80 % and 90 % of firms in most economies, both developed and growing (Family Business Index, 2023).

Multiple factors determine innovation in family firms (Aparicio et al., 2019; Calabrò et al., 2019). Specifically, we focus on two factors: entrepreneurship (Casillas & Moreno, 2010; Zahra et al., 2004) and absorptive capacity (Cepeda-Carrión et al., 2012; Kotlar et al., 2020). Entrepreneurship can be measured in several ways, although there is consensus that entrepreneurial orientation is one of the most appropriate measures, as it is an antecedent of innovation (Rhee et al., 2010; Zeebarree & Siron, 2017). Entrepreneurial orientation has been the subject of multiple investigations (Covin & Wales, 2012) and it has undergone various reformulations. In this study, we adopt Miller (1983) and Covin and Slevin's (1989) definition, which states that the characteristics that best define entrepreneurial orientation are innovation, proactivity, and risk-taking, as these capture entrepreneurial behavior (Basco et al., 2020).

The second factor considered is absorptive capacity. This dynamic capability (Wang & Ahmed, 2007), the definition of which has also evolved over time since the seminal work of Zahra and George (2002), has developed in a prolific body of knowledge (Volberda et al., 2010). Absorptive capacity can be defined as the ability to explore, assimilate, transfer, and apply new knowledge (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Zahra & George, 2002). Numerous studies have pointed out that absorptive capacity determines innovation (Calabrò et al., 2019; Garcés-Galdeano et al., 2024; Kotlar et al., 2020). However, although a large body of the literature has focused on absorptive capacity, few studies analyze absorptive capacity in family firms (Garcés-Galdeano et al., 2024).

Theoretical implicationsEntrepreneurial orientation, characterized by innovation, proactivity, and risk-taking, significantly shapes entrepreneurial behavior, with innovation playing the largest role. These dimensions have high reliability and validity and they positively impact absorptive capacity, particularly in how companies exploit and disseminate the acquired knowledge, which boosts their competitiveness. The proposed model highlights that entrepreneurial orientation has the greatest influence on innovative capacity, which is driven by both product and process innovation. Additionally, it confirms that both entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity are key antecedents of innovation in family businesses.

Managerial implicationsInnovation remains a key factor in improving the competitiveness and performance of family businesses. To enhance their innovative capacity, family firms should focus on entrepreneurial orientation, thereby fostering entrepreneurial behavior through innovation. In terms of absorptive capacity, they should consider what type of knowledge needs to be acquired and how it should be utilized to improve their outcomes and competitiveness. Both process innovation and product innovation are equally important for family businesses. When innovating, they must focus on improving both products and processes. Family business management should consider that innovative capacity is widespread and relevant for generating value, regardless of the industry, age, or size of the company.

Limitations and future researchThis study has some limitations. First, the questionnaires were sent only to CEOs, which means that the information was collected from a single source in each firm. To address this limitation, after sending the questionnaires to the CEOs in the companies (Zotto & Van Kranenburg, 2008), we followed the recommendations of Torchiano et al. (2013) on the participation of family business CEOs in the process and explained the study's objective. We also provided an email and telephone number to answer any questions that might arise. Additionally, we monitored the process and sent reminders to complete the questionnaires at regular intervals (Rong & Wilkinson, 2011; Woodside, 2013; Woodside et al., 2015).

Second, the companies in the sample may share certain characteristics because all of them are associated with the Institute of Family Business in Spain. Since other family companies may be associated with institutes other than this one (e.g., those found in the Iberian Balance Sheet Analysis System database), the results may not be fully generalizable.

Future research should explore how different dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation such as competitive aggressiveness and autonomy (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996) affect innovation in family firms. A deeper understanding of how these dimensions influence both product and process innovation would provide valuable insights for family firms seeking to optimize their innovation strategies. Furthermore, examining the impact of external factors such as market turbulence and technological shifts on the relationships among entrepreneurial orientation, absorptive capacity, and innovative capacity would enrich the literature.

Additionally, longitudinal studies could provide more detailed insights into how entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity evolve over time within family firms. Given that family firms often span multiple generations, understanding how innovative capacity changes across generational transitions and leadership shifts would offer valuable guidance for practitioners.

Finally, comparative studies between family and non-family firms in different cultural and geographical contexts would provide a broader perspective on the universal and unique factors influencing innovation in family businesses.

CRediT authorship contribution statementFelipe Hernández-Perlines: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Alicia Blanco-González: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Giorgia Miotto: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Composite reliability: According to Fornell and Larcker (1981), composite reliability values should be above 0.7, with suitable values ranging between 0.7 and 0.9 (Hair et al., 2018). Additionally, as no value exceeds 0.95, there are no redundancy problems (Diamantopoulos et al., 2012; Drolet & Morrison, 2001).

Cronbach's alpha: Cronbach's alpha values should exceed 0.7 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Rho a: Rho a should be greater than 0.7 (Dijkstra & Henseler, 2015) and should fall between the values of composite reliability and Cronbach's alpha (Hair et al., 2018).

AVE: AVE is used to assess the convergent validity of each composite. Fornell and Larcker (1981) recommend an AVE value above 0.5.

HTMT ratio: This ratio is used to measure discriminant validity. To maintain discriminant validity, the correlation between each pair of constructs should not be greater than the square root of the AVE of each construct, that is, HTMT values must be below 0.85 (Henseler et al., 2015).