This study investigates how the discrete emotions expressed by travel influencers on YouTube influence viewer engagement, distinguishing between macro- and micro- influencers. Using text mining and machine learning techniques, 6,061 travel-related videos were analyzed. The results indicate that high-arousal negative emotions such as anger and disgust enhance engagement for macro-influencers but reduce engagement for micro- influencers. Conversely, low-arousal negative emotions, such as fear and sadness, increase engagement levels for micro-influencers, while decreasing them for macro-influencers. Positive emotions enhance engagement, particularly among micro-influencers. These insights can inform emotional strategies in influencer marketing.

The field of influencer marketing is expanding, with estimates indicating that expenditures on YouTube influencer marketing are expected to increase by approximately 40% by 2024. The worldwide influencer marketing industry, valued at $16.4 billion in 2022, is projected to reach $24 billion by the end of 2024 (Influencer Marketing Hub, 2024). YouTube has transformed the travel industry and marketing by enabling influencers to share captivating stories that were previously unattainable through traditional media. This facilitates the creation of high-quality videos by integrating interactive elements to generate captivating travel content that effectively engages viewers. This innovative approach enriches viewer engagement and offers marketers novel avenues to connect with prospective travelers. The capacity for diverse forms of content, ranging from video blogs to comprehensive travel guides, has revolutionized the dissemination and consumption of travel information (Lombardo, 2024), fostering a deeper and more significant relationship between influencers and their followers. Given the intangible and empirical nature of tourism products, ongoing academic interest focuses on how potential tourists will receive, process, and be influenced by various forms of external information (Choi, 2020).

Travel influencers share personal anecdotes, first-hand experiences, and suggestions that resonate with audiences (De Veirman et al., 2019). This personalized content enables a stronger sense of affiliation among followers toward the influencer and, consequently, toward the endorsed destinations. This affiliation is frequently strengthened by the parasocial bonds between followers and influencers, wherein followers perceive personal familiarity with the influencer, even without physical interaction (Bhattacharya, 2022; Horton &Wohl, 1956). Understanding these connections offers valuable knowledge for creating novel marketing strategies that capitalize on the emotional connections between influencers and their followers.

Emotions are crucial in the formation and maintenance of parasocial relationships. Emotional involvement with personalities in media can heighten an audience's perception of closeness and allegiance (Giles, 2002). When influencers disseminate materials that authentically convey emotions, viewers are more inclined to experience a sense of connection and investment with their creator. Consequently, this enriches the quality of their parasocial relationships. This emotional affinity can stimulate increased levels of interaction, such as liking, commenting, and sharing content, while also fostering greater loyalty toward the content creator (Eyal & Dailey, 2012). Nevertheless, despite the recognized significance of emotions in these contexts, a comprehensive understanding of how distinct emotional manifestations by content creators influence audience engagement, particularly within the tourism domain, remains insufficient.

This study analyzes the impact of discrete emotions conveyed by YouTube travel influencers on viewer engagement, focusing specifically on the contributions of macro- and micro-influencers. Specifically, this study investigates the following: (1) the influence of high-arousal negative emotions expressed by macro- (versus micro-) travel influencers on viewers’ engagement levels; (2) influence of low-arousal negative emotions expressed by macro- (versus micro-) travel influencers on viewers’ engagement levels; and (3) influence of positive emotions expressed by travel influencers on viewers’ engagement levels.

Specifically, the present study utilizes text-mining methodologies to examine emotions in video narration using the Syntax-Aware Lexical Emotion Engine (SALLEE) module sourced from the Receptiviti API, which is grounded in the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) framework. These advanced data science techniques, including machine learning algorithms and predictive modeling, augment the analysis’ precision and comprehensiveness by uncovering subtle emotional trends within extensive datasets. Such methodologies contribute substantially to digital marketing analysis by providing practical insights (Saura, 2021). Applying these methodologies to travel-related content on YouTube provides valuable advancements in both scholarly investigations and marketing tactics, helping marketers and influencers optimize their content to enhance audience engagement.

Literature reviewTravel content and influencer dynamics on youtubeYouTube has emerged as a crucial platform in the travel sector because of its capacity to present long-form detailed content that effectively showcases travel destinations and experiences. Introducing this platform has significantly advanced promotional strategies in the travel industry by empowering influencers to present elaborate visual narratives previously unattainable through traditional media. By incorporating top-notch video production alongside interactive features, YouTube provides influencers to create compelling travel content that deeply engages viewers. This innovative methodology not only enriches viewer interaction but also provides marketers with new opportunities to reach and influence potential travelers. The platform's ability to accommodate a broad spectrum of content types, ranging from video blogs to meticulous destination overviews, has revolutionized disseminating and consuming travel-related information. This, consequently, fosters a more intimate and influential bond between influencers and their followers.

YouTube enables influencers to merge visual narratives with interactive elements, thereby amplifying viewer engagement and broadening the knowledge base for digital marketing strategies. YouTube's interactive nature enables influencers to cultivate a strong sense of community among followers. This communal aspect nurtures allegiance and confidence, making viewers more susceptible to travel suggestions from their preferred influencers. Personal bonds that influencers forge with their audiences are particularly potent in the travel industry, where recommendations and shared experiences significantly influence destination choices (Mqwebu, 2024). Consumers are more likely to trust and be influenced by recommendations from influencers than traditional advertisements, making influencers highly effective in driving travel decisions (Rajput & Gandhi, 2024).

The influencers vary widely in their branding focus, follower base, engagement rate, and collaboration costs. This diversity affects the overall value they offer audiences and their ability to influence travel decisions (Rajput & Gandhi, 2024). Campbell and Farrell (2020) introduced a valuable typology that categorizes five distinct influencer types based on their follower counts. This hierarchy includes celebrity influencers and mega-influencers who boast followings exceeding one million, followed by macro-influencers (100,000 to one million followers), micro-influencers (10,000 to 100,000 followers), and nano-influencers (fewer than 10,000 followers).

Classifying influencers is a complex issue that extends beyond assessing follower counts alone. As Campbell and Farrell (2020) observed, influencers perform several functions, including audience reach, content creation, endorsement credibility, and audience management. This multifaceted nature of influencers indicates that while follower count serves as a convenient and widely accepted categorization method, it does not fully capture the nuances of influencer impact. Conde and Casais (2023) posited that these categorizations may change depending on the particular context in which influencers operate. For example, a celebrity influencer may be classified as a macro-influencer in one context and a micro-influencer in another, depending on the specific number of followers in question.

This study acknowledges these discrepancies but concentrates on follower numbers as a principal indicator, given the well-established correlation between this metric and marketing efficacy on platforms such as YouTube (Campbell & Farrell, 2020). Specifically, this study categorizes the four influencer types, excluding celebrities, into two broad groups based on the trade-off between popularity and intimacy. Mega- and macro-influencers enjoy higher follower counts and broader popularity, whereas micro- and nano-influencers typically engender a stronger sense of intimacy with their audiences (Campbell & Farrell, 2020). For convenience, the terms “macro-influencers” and “micro-influencers” will be used throughout this paper to refer to the two main categories of social media influencers.

Macro-influencers (i.e., those with 100,000–1000,000 followers) are frequently viewed as authoritative individuals with significant knowledge in their specific fields (Şanli & Ceylan, 2023). Their extensive influence enables them to affect a large audience; however, this brings about distinct benefits and challenges. Macro-influencers commonly receive high ratings regarding perceived expertise and credibility because of their large follower base and well-established presence (Evans & Stanovich, 2013). Şanli and Ceylan (2023) determined that the perceived authority of macro-influencers strengthens the effectiveness of their communications, resulting in higher levels of viewer engagement. Conversely, the broad and diverse audiences of macro-influencers may weaken the perceived intimacy and authenticity of their interactions (Steils et al., 2022).

Parasocial interaction theory describes the one-sided relationships that viewers develop with media personalities. In these relationships, viewers feel a personal connection, although they have no real-life interactions (Horton & Wohl, 1956). While macro-influencers benefit from their authoritative presence, their parasocial relationships may not be as strong as those cultivated by micro-influencers (Conde & Casais, 2023).

Micro-influencers (i.e., those with fewer than 100,000 followers) often cultivate closer and more intimate connections with their audience (Britt et al., 2020). They are perceived as more relatable and authentic, resulting in stronger parasocial relationships (Ong et al., 2022). Authenticity and perceived personal connections with micro-influencers are pivotal in shaping how their content is received and engaged with by followers. Followers of micro-influencers develop stronger emotional attachments due to the perceived authenticity and intimacy in their engagements (Horton & Wohl, 1956). The intrinsic essence of their content cultivates a sense of proximity and reliance, leading to a higher probability of active engagement from their audience (Campbell & Farrell, 2020).

The source credibility theory underscores the significance of micro-influencers’ perceived trustworthiness (Hovland et al., 1953). Although they may lack the large follower base that macro-influencers possess, their trustworthiness renders them particularly adept at fostering engagement through authentic content (Conde & Casais, 2023). Trustworthiness plays a vital role in online consumer behavior and cognitive, affective, and behavioral involvement. When viewers perceive an influencer's content as reliable, they are more likely to believe the information and engage with the content (Obeidat et al., 2022).

Impact of discrete emotions expressed by travel influencersThe different aspects of perceived authenticity, credibility, and audience relationships between micro- and macro-influencers significantly affect how their messages resonate with and influence viewers. The emotional tone of content plays a crucial role in capturing viewers’ attention, shaping their perceptions of the destination, and driving engagement. Moreover, emotional responses to content can enhance memory retention, making it more likely for viewers to remember and act on the travel information presented (Rao Hills & Qesja, 2023). Emotions also cultivate a sense of connection and relatability, fostering a deeper sense of personal involvement with content and influencers (Horton & Wohl, 1956). Establishing an emotional bond can build trust and loyalty, encourage viewers to adhere to influencers’ suggestions, and share content with others (Jin et al., 2019). Through the strategic use of emotional appeal, travel influencers craft engaging, persuasive, and memorable content that deeply resonates with their audiences, leading to heightened involvement and a stronger impact on travel-related choices.

Negative emotions in youtube travel content: High- versus Low-Arousal negative emotionsThe appraisal theory of emotion posits that emotions stem from the evaluations (appraisals) individuals make of events based on their relevance to personal goals and well-being (Lazarus, 1991). Negative emotions with high arousal levels such as anger and disgust result from specific cognitive evaluations and exhibit distinct psychological consequences. Anger typically arises from assessments of goal obstruction and attribution of blame, leading individuals to experience a profound sense of unfairness and motivating them to rectify their perceived injustices (Lazarus, 1991). Conversely, disgust is activated through evaluations of contamination or moral violations, prompting individuals to experience aversion and a desire to separate themselves from the source of disgust (Rozin et al., 2009). In contrast, low-arousal negative emotions such as fear and sadness are derived from distinct cognitive evaluations. Fear is linked to the sensing of threats and imminent danger, triggering feelings of anxiety and the desire to avoid threats (Lerner & Keltner, 2001). Sadness arises from assessments of deprivation or powerlessness, leading to experiences of sorrow and retreat (Smith & Ellsworth, 1985).

This theoretical framework helps elucidate the various effects of distinct negative emotions on viewer engagement. High-arousal emotions such as anger and disgust provoke immediate and intense reactions because of their link to perceived threats or moral transgressions. Contrastingly, low-arousal emotions such as fear and sadness evoke more passive reactions characterized by contemplation (Ellsworth & Scherer, 2003). The impact of negative emotions on engagement varies, depending on the type of influencer. Macro-influencers are often perceived as authoritative figures with substantial expertise in their respective domains (Jin & Phua, 2014). Their broad reach and established authority and expertise enable them to effectively leverage high-arousal emotions, such as anger and disgust, to drive engagement.

The cognitive appraisal theory suggests that individuals’ responses to events are based on their cognitive evaluations or appraisals of those events (Scherer, 1984). Macro-influencers’ expressions of anger and disgust are likely to be perceived by their audiences as an indication of significant concerns or injustices. The opinions expressed by these influencers are assumed to be based on expertise and knowledge, which make their expressions of anger and disgust more compelling and persuasive (Hovland et al., 1953). Furthermore, the broad and diverse audiences of macro-influencers amplify the effects of high-arousal negative emotions. High-arousal emotions, such as anger and disgust, can resonate widely, tapping into shared concerns or moral outrage among large groups of followers. This shared resonance can drive significant engagement, as viewers feel compelled to react and express their opinions (Wang et al., 2019). Macro-influencers’ ability to amplify collective sentiments is particularly effective in driving engagement because these emotions often prompt immediate and strong reactions.

This study expects that when macro-travel influencers express anger and disgust in their travel content, they are likely to interpret these emotions as highlighting significant issues or injustices related to travel experiences, such as poor service, unethical practices, or safety concerns, prompting strong engagement responses as measured by the number of likes and comments. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1

For macro-travel influencers, the expressions of high-arousal negative emotions (anger and disgust) positively affect engagement levels (likes and comments).

The impact of low-arousal negative emotions on engagement levels can present a multifaceted scenario for macro-influencers. Although macro-influencers are perceived as credible and authoritative, the breadth and diversity of their audiences could diminish the personal connection vital for low-arousal emotions to stimulate engagement efficiently. Fear and sadness are typically associated with low-arousal and passive responses. Fear arises from the appraisal of threats, leading to avoidance behavior (Lerner & Keltner, 2001), whereas sadness stems from perceptions of loss and often results in a more reflective, less interactive response (Smith & Ellsworth, 1985).

For macro-influencers, a large and heterogeneous audience may not consistently evaluate these emotions as directly relevant or sufficiently compelling to promote active engagement. This may explain the lack of consistent resonance for expressions of fear and sadness by macro-influencers, as their followers have varied interests and emotional stimuli. Therefore, these emotions will not evoke unified and impactful feedback. Jin and Phua (2014) indicate that as influencers gain more followers, the perceived levels of intimacy and authenticity in their engagements decrease, potentially diminishing the efficacy of emotional appeals grounded in personal connections and empathy. Furthermore, avoidance behaviors typically elicited by fear and passive consumption associated with sadness can lead to lower engagement levels. Empirical studies support this discussion, indicating that low-arousal emotions such as fear and sadness generally result in lower engagement levels on YouTube, particularly for influencers with broad reach (Stappen et al., 2022).

Therefore, this study posits that macro-travel influencers may face challenges in leveraging low-arousal negative emotions, such as fear and sadness, to drive engagement. Their broad and diverse audience base combined with the inherently passive nature of these emotions results in lower engagement levels. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2

For macro-influencers, the expressions of low-arousal negative emotions (fear and sadness) negatively affect engagement levels.

Unlike macro-influencers, micro-influencers often establish direct personal relationships with their audiences (Jin et al., 2019). They frequently share personal travel experiences, recommendations, and honest reviews that resonate with their audiences and are perceived as more relatable and authentic, leading to stronger parasocial relationships. Parasocial relationship theory posits that individuals establish one-sided, intimate relationships with media personalities and experience personal connections despite the absence of real-life interactions (Horton & Wohl, 1956).

However, when micro-influencers express high-arousal emotions, their followers may appraise them as excessively intense or inauthentic. Subsequently, this can undermine the influencer's perceived authenticity and trustworthiness (Horton & Wohl, 1956; Jin et al., 2019). For instance, if a micro-influencer shares a travel video expressing intense anger about a delayed flight or disgust over poor hotel conditions, viewers may perceive these reactions as exaggerated or insincere. This perceived inauthenticity can alienate followers who expect genuine and relatable content from trusted influencers (Haenlein et al., 2020). For micro-influencers, expressions of anger and disgust might be appraised by followers as excessive or unwarranted, especially in the context of travel content, where viewers look for informative and enjoyable experiences. This appraisal leads to decreased engagement as viewers distance themselves from perceived negativity. The intimate and authentic nature of micro-influencers’ interactions with their audiences implies that high-arousal negative emotions can disrupt the expected emotional tone, reducing the perceived sincerity of the content (Hughes et al., 2019).

This study anticipates that when micro-travel influencers express high-arousal negative emotions, such as anger and disgust, their followers are likely to perceive these emotions as overly intense or inauthentic, leading to decreased engagement. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3

For micro-influencers, the expressions of high-arousal negative emotions negatively affect engagement levels.

By contrast, when micro-influencers convey low-arousal negative emotions in their travel-related content, their followers are more likely to perceive these emotions as authentic and relatable. The expression of fear or sadness in the travel context can elicit empathy and support from followers, thereby reinforcing the influencer's authenticity and the perceived sincerity of their content (Haenlein et al., 2020; Jin et al., 2019). Displaying such emotional expressions can help establish relatable and authentic relationships between influencers and their followers, thereby strengthening their bonds. In the context of travel content, the expression of such emotions can highlight the inherent challenges and unpredictability of a travel experience, thereby enhancing the authenticity of an influencer's narrative. Authenticity in sharing vulnerabilities can lead to stronger emotional connections and increased engagement as followers connect at a deeper emotional level (Hughes et al., 2019). This study proposes the following hypothesis:

H4

For micro-influencers, the expressions of low-arousal negative emotions positively affect engagement levels.

Positive emotions in youtube travel contentPositive emotions, such as joy and surprise, can also enhance viewer engagement (Hughes et al., 2019). Joy can be described as an emotion associated with happiness, satisfaction, and the general state of welfare (Fredrickson, 2001). Regarding travel content, joy is often expressed through the excitement of exploring new destinations, pleasure derived from experiencing unique cultures, and enjoyment associated with sharing memorable experiences (Fredrickson, 2001). Joy is also effective at fostering a sense of connection and community among viewers (Hsu & Lin, 2020). Positive affect associated with joy enhances the parasocial relationships that viewers develop with influencers, making their content more impactful and memorable (Fredrickson, 2001).

Surprises arise from unexpected and novel experiences (Meyer et al., 1997). This is especially potent in terms of travel content, from which viewers seek novel and unique experiences. Surprise captures immediate attention and enhances the memorability of content by breaking through the mundane and presenting it unexpectedly. This emotion is effective in engaging viewers because it piques their curiosity and encourages them to interact with the content to discover surprising elements being presented (Hsu & Lin, 2020). The element of surprise, coupled with its intrinsic unpredictability, can provoke increased viewer interaction as viewers become immersed in content and are inspired to express their responses.

The social sharing of emotions (SSE) theory posits that individuals have an intrinsic drive to disseminate their emotional experiences to others, a process that amplifies and propagates these emotions through social networks (Rimé, 2009). This need for sharing is particularly potent in the digital age, in which social media platforms facilitate the rapid spread of emotions across vast networks. Positive emotions such as joy and surprise are especially prone to this amplification because of their inherently pleasurable nature and the human tendency to save and capitalize on positive experiences (Gable et al., 2018; Langston, 1994). Rimé (2009) argued that positive emotions lead to a process of social sharing that enhances the emotional experiences of both sharers and recipients. This phenomenon occurs because recounting positive events not only rekindles original positive feelings but also reinforces social bonds and generates additional positive affect through the reactions of the audience (Gable et al., 2018). In the context of travel content, this sharing process is magnified as platforms such as YouTube enable travel influencers to broadcast their emotional experiences, such as the joy of unique cultural encounters, to large audiences. In turn, these audiences share their emotions with their networks, creating a ripple effect of enhanced engagement and the dissemination of positive travel experiences (Rimé, 2009).

The mechanism of emotional contagion delineated by Hatfield et al. (1993) provide further support for this discourse. The concept of emotional contagion suggests that the reflection mechanism occurs through the unconscious imitation of facial expressions, vocal inflections, and gestures, which ultimately leads to the onlooker experiencing a comparable affective condition (Barsade, 2002; Hatfield et al., 1993). This synchronization leads to shared emotional experiences that can significantly drive engagement levels on social media. For example, travel influencers who express positive emotions while exploring breathtaking landscapes, participating in local festivals, or finding an intriguing historical site are likely to experience similar positive emotions. Emotional mirroring increases the likelihood of liking, commenting on, and sharing content, further propagating emotions (Hatfield et al., 1993). Barsade (2002) and Bono and Ilies (2006) indicate that emotional contagion can foster group cohesion and collective emotional experiences; when a travel influencer's positive emotions resonate with viewers, this shared emotional state can create a sense of community and collective enjoyment, driving higher levels of engagement.

Given these theoretical underpinnings, this study anticipates that the positive emotions expressed by both macro- and micro-travel influencers on YouTube positively affect their engagement levels. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5

For both macro- and micro-influencers, the expression of positive emotions positively affects engagement levels.

MethodologySampling and data crawlingTo examine the research hypotheses, a dataset comprising 6061 travel-related English-language videos from YouTube was used. First, nine cities from three categories of destination image (Beerli & Martins, 2004) were chosen from Euromonitor's list of the world's most visited cities for a diverse representation of destinations. These cities included Macau, Phuket, and Miami for the leisure/natural environment category; Paris, Rome, and Istanbul for culture, history, and art; and Tokyo, London, and New York City for metropolitan areas. The videos were collected using a web crawling approach, targeting travel-related videos on YouTube. The specific criterion for selecting videos was the inclusion of the terms “travel,” “trip,” or “tour” in conjunction with the name of the city in either the video title or the introductory description.

To ensure that the analysis focused on genuine influencer content and its impact on user engagement, promotional videos posted by travel agencies or organizations were filtered out. Two human coders manually examined the videos after extensive training and meetings to ensure consistent inter-coder reliability. The coders independently evaluated a subset of 100 videos and classified them into two categories based on predefined coding guidelines: videos created by individual users and those created by commercial organizations. Subsequent discussions and exchanges of findings between the coders facilitated the resolution of discrepancies. Intercoder reliability was assessed using Holsti's (1969) reliability coefficient; it yielded a value of 0.92, which is considered satisfactory (Holsti, 1969; Wimmer & Dominick, 1987). Consequently, 5008 videos were deemed suitable for further analysis.

After the selection procedure, data extraction was performed using the Amazon Rekognition API, a machine learning model developed by Amazon Web Services (AWS), to facilitate the analysis of video content features. This analysis involved downloading web video text track (WebVTT) files, which provided a textual representation of the audio content; these were subsequently stored in the JSON format. Acknowledging the variability in video length, a median duration of 9 min and 30 s was established as the threshold. Videos exceeding this length were truncated to ensure that only the content within this time frame was analyzed. Shorter videos were included entirely.

Data collection processWe employed text-mining techniques utilizing a lexicon-based approach to analyze emotions in video narration. Lexicon-based methods involve using a predefined list of words associated with various emotions, where each word in the lexicon is tagged with a specific emotional state or value. This method relies on the presence and frequency of predefined emotional words within a text to infer the overall emotional content. This is advantageous because of the accessibility of the emotion lexicon and transparency of its automated coding process (Wu & Chang, 2020).

Specifically, we utilized the Syntax-Aware Lexical Emotion Engine (SALLEE) module from the Receptiviti API, which builds on a Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) framework. LIWC is widely recognized for its ability to analyze text and quantify various linguistic aspects including emotional, cognitive, and structural components (Tausczik and& Pennebaker, 2010). It is particularly popular for sentiment analysis in social media research because it robustly detects overall sentiments (positive or negative) and specific emotions such as anger, sadness, and anxiety (Golbeck, 2016).

SALLEE enhances the capabilities of LIWC by including more detailed emotions, such as fear, disgust, joy, and surprise (Ireland et al., 2023), and by measuring emotional intensity and valence more accurately through syntax-aware features. These features consider the context of words such as negations, intensifiers, emoticons, and swear words and adjust the significance in emotional categories based on their proximity. For instance, SALLEE can distinguish between “not really happy” and “really not happy.” SALLEE's emotional scores align closely with individuals’ self-reported emotions, often more accurately than those measured by the LIWC (Ireland et al., 2022; Rathi et al., 2022). Researchers have applied SALLEE to analyze emotions in text-based social media posts, demonstrating its utility in contemporary research (Ireland et al., 2023; Rathi et al., 2022).

Additionally, we collected the number of likes and comments along with other descriptive characteristics of the video posts to serve as control variables.

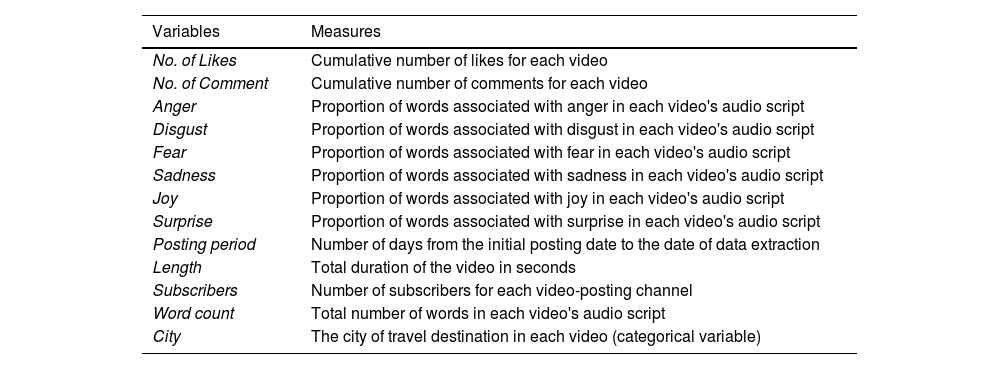

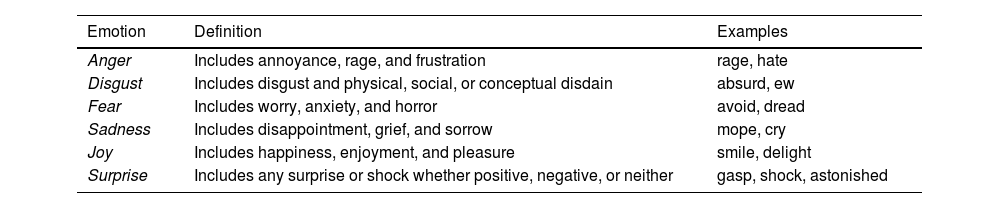

VariablesTable 1 presents the variables used in the analysis. The dependent variable, the number of likes and comments, represents the cumulative count of likes and comments received from each video. The independent variables were four negative emotions (anger, disgust, fear, and sadness) and two positive emotions (joy and surprise), defined based on Ekman's (1971) emotional dimensions. As previously described, SALLEE extracts emotional words and assesses their intensity and valence by considering contextual negations. Table 2 provides examples of the words recognized by SALLEE for each emotion. All the emotional scores range from 0.0 to 1.0.

Measurement of variables.

| Variables | Measures |

|---|---|

| No. of Likes | Cumulative number of likes for each video |

| No. of Comment | Cumulative number of comments for each video |

| Anger | Proportion of words associated with anger in each video's audio script |

| Disgust | Proportion of words associated with disgust in each video's audio script |

| Fear | Proportion of words associated with fear in each video's audio script |

| Sadness | Proportion of words associated with sadness in each video's audio script |

| Joy | Proportion of words associated with joy in each video's audio script |

| Surprise | Proportion of words associated with surprise in each video's audio script |

| Posting period | Number of days from the initial posting date to the date of data extraction |

| Length | Total duration of the video in seconds |

| Subscribers | Number of subscribers for each video-posting channel |

| Word count | Total number of words in each video's audio script |

| City | The city of travel destination in each video (categorical variable) |

Sample words for emotions in SALLEE.

| Emotion | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Anger | Includes annoyance, rage, and frustration | rage, hate |

| Disgust | Includes disgust and physical, social, or conceptual disdain | absurd, ew |

| Fear | Includes worry, anxiety, and horror | avoid, dread |

| Sadness | Includes disappointment, grief, and sorrow | mope, cry |

| Joy | Includes happiness, enjoyment, and pleasure | smile, delight |

| Surprise | Includes any surprise or shock whether positive, negative, or neither | gasp, shock, astonished |

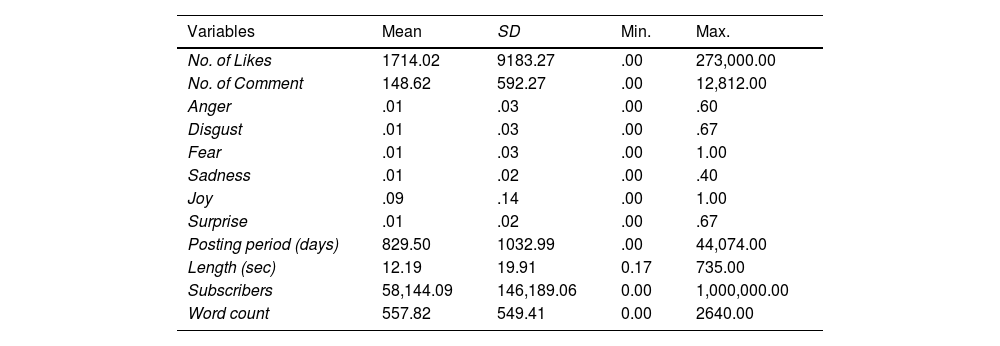

We also incorporate five control variables into the analysis. The posting period was defined as the number of days from the initial posting date to the date of data extraction. Video length was quantified as the total duration of the video (min). The number of subscribers is measured for each video-posting channel. We also included total word count and city as control variables. The descriptive statistics are summarized in Table 3.

Descriptive statistic results of variables.

| Variables | Mean | SD | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Likes | 1714.02 | 9183.27 | .00 | 273,000.00 |

| No. of Comment | 148.62 | 592.27 | .00 | 12,812.00 |

| Anger | .01 | .03 | .00 | .60 |

| Disgust | .01 | .03 | .00 | .67 |

| Fear | .01 | .03 | .00 | 1.00 |

| Sadness | .01 | .02 | .00 | .40 |

| Joy | .09 | .14 | .00 | 1.00 |

| Surprise | .01 | .02 | .00 | .67 |

| Posting period (days) | 829.50 | 1032.99 | .00 | 44,074.00 |

| Length (sec) | 12.19 | 19.91 | 0.17 | 735.00 |

| Subscribers | 58,144.09 | 146,189.06 | 0.00 | 1,000,000.00 |

| Word count | 557.82 | 549.41 | 0.00 | 2640.00 |

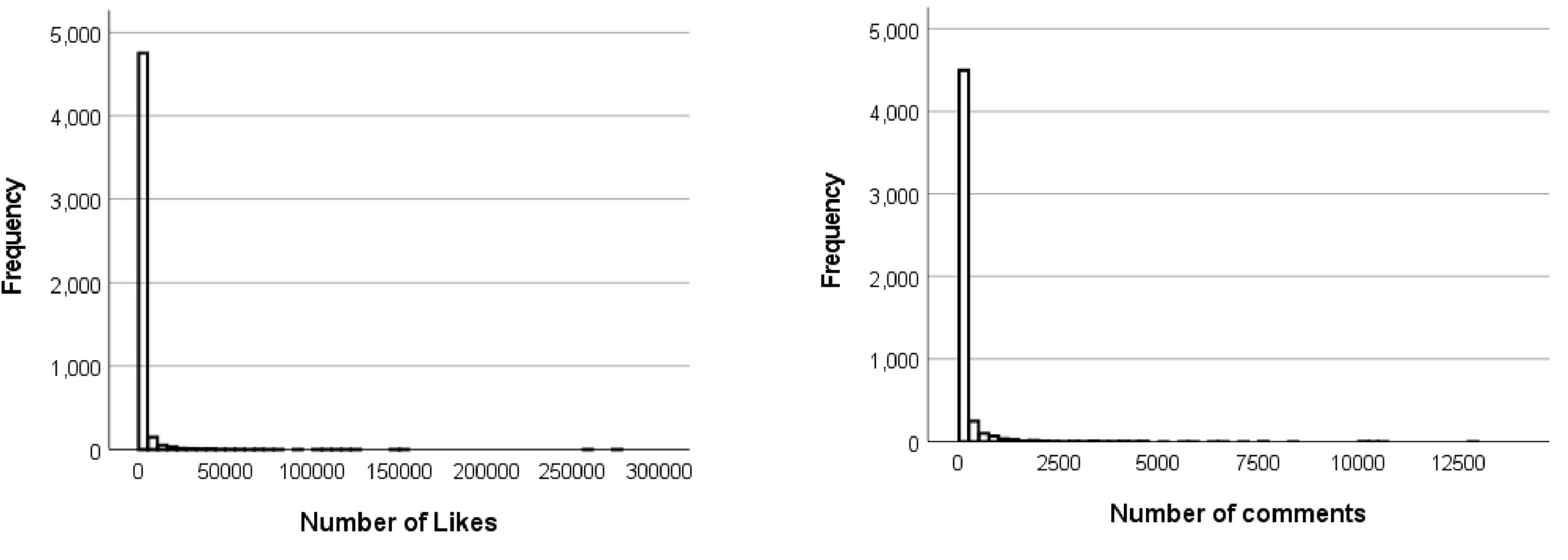

Owing to the observed overdispersion of multiple variables, we employed a negative binomial distribution for the analysis, in line with previous studies (Hughes et al., 2019; Munaro et al., 2021; Van Laer et al., 2019). The negative binomial regression model is an extension of the Poisson regression model and is well suited for counting data exhibiting overdispersion, where the mean and variance are not equal (Wang et al., 2019). The number of likes and comments displayed left-skewed distributions that deviated from normality (Fig. 1).

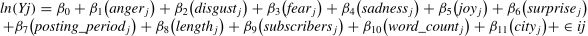

The model for each variable can be represented as:

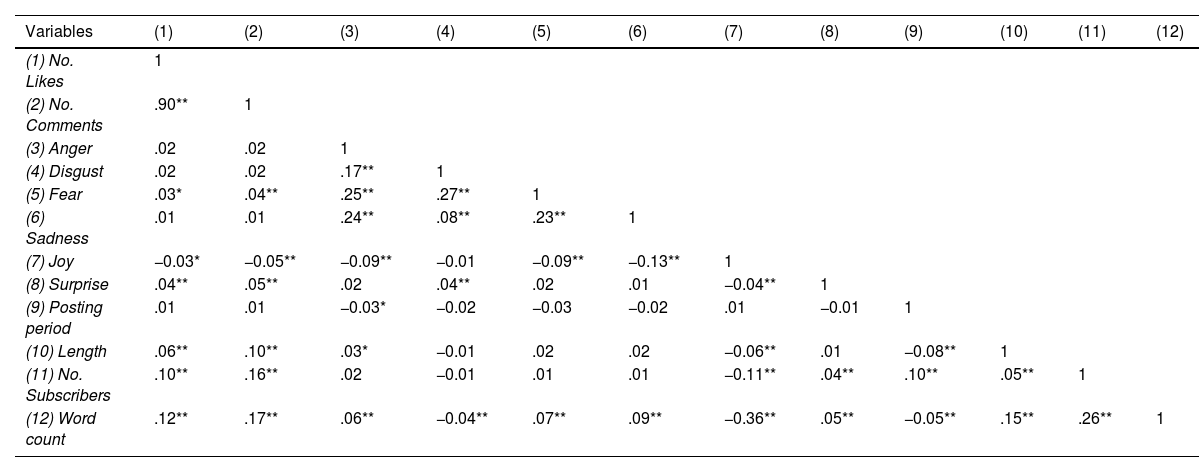

where Yj represents the count of likes for the video j, β0 is the intercept term, and ∈ij is the distributed error terms for dependent variables X1, X2, ..., Xk, respectively.Hypothesis testingMulticollinearity was assessed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and correlations among the predictor variables. While the VIF values indicate no evidence of multicollinearity (ranging from 1.006 to 1.248), the correlation table reveals significant associations among some of the predictor variables (see Table 4). Despite these significant correlations, the VIF values remained within an acceptable range, all below the commonly recommended threshold of five (Hair et al., 2011), suggesting that multicollinearity is not a concern in the negative binomial regression model.

Correlation matrix of variables.

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) No. Likes | 1 | |||||||||||

| (2) No. Comments | .90** | 1 | ||||||||||

| (3) Anger | .02 | .02 | 1 | |||||||||

| (4) Disgust | .02 | .02 | .17** | 1 | ||||||||

| (5) Fear | .03* | .04** | .25** | .27** | 1 | |||||||

| (6) Sadness | .01 | .01 | .24** | .08** | .23** | 1 | ||||||

| (7) Joy | −0.03* | −0.05** | −0.09** | −0.01 | −0.09** | −0.13** | 1 | |||||

| (8) Surprise | .04** | .05** | .02 | .04** | .02 | .01 | −0.04** | 1 | ||||

| (9) Posting period | .01 | .01 | −0.03* | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.02 | .01 | −0.01 | 1 | |||

| (10) Length | .06** | .10** | .03* | −0.01 | .02 | .02 | −0.06** | .01 | −0.08** | 1 | ||

| (11) No. Subscribers | .10** | .16** | .02 | −0.01 | .01 | .01 | −0.11** | .04** | .10** | .05** | 1 | |

| (12) Word count | .12** | .17** | .06** | −0.04** | .07** | .09** | −0.36** | .05** | −0.05** | .15** | .26** | 1 |

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

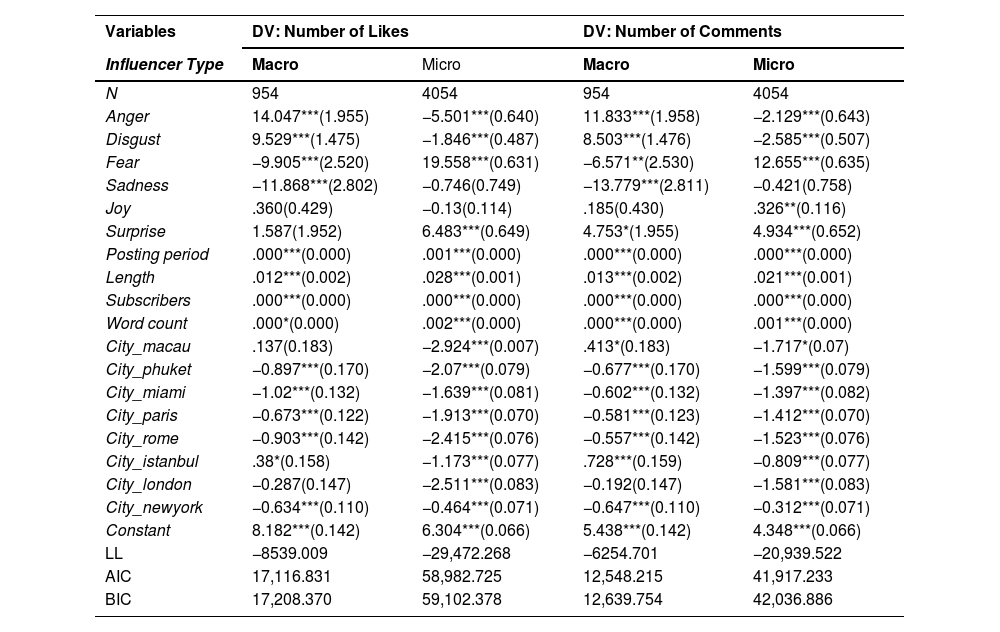

Table 5 presents the results of the negative binomial regression analysis. All control variables showed significant influences on likes and comments in the negative binomial regression model. Posting period, video length, number of subscribers, and word counts had positive effects on likes and comments.

Results of negative binomial regression.

| Variables | DV: Number of Likes | DV: Number of Comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influencer Type | Macro | Micro | Macro | Micro |

| N | 954 | 4054 | 954 | 4054 |

| Anger | 14.047***(1.955) | −5.501***(0.640) | 11.833***(1.958) | −2.129***(0.643) |

| Disgust | 9.529***(1.475) | −1.846***(0.487) | 8.503***(1.476) | −2.585***(0.507) |

| Fear | −9.905***(2.520) | 19.558***(0.631) | −6.571**(2.530) | 12.655***(0.635) |

| Sadness | −11.868***(2.802) | −0.746(0.749) | −13.779***(2.811) | −0.421(0.758) |

| Joy | .360(0.429) | −0.13(0.114) | .185(0.430) | .326**(0.116) |

| Surprise | 1.587(1.952) | 6.483***(0.649) | 4.753*(1.955) | 4.934***(0.652) |

| Posting period | .000***(0.000) | .001***(0.000) | .000***(0.000) | .000***(0.000) |

| Length | .012***(0.002) | .028***(0.001) | .013***(0.002) | .021***(0.001) |

| Subscribers | .000***(0.000) | .000***(0.000) | .000***(0.000) | .000***(0.000) |

| Word count | .000*(0.000) | .002***(0.000) | .000***(0.000) | .001***(0.000) |

| City_macau | .137(0.183) | −2.924***(0.007) | .413*(0.183) | −1.717*(0.07) |

| City_phuket | −0.897***(0.170) | −2.07***(0.079) | −0.677***(0.170) | −1.599***(0.079) |

| City_miami | −1.02***(0.132) | −1.639***(0.081) | −0.602***(0.132) | −1.397***(0.082) |

| City_paris | −0.673***(0.122) | −1.913***(0.070) | −0.581***(0.123) | −1.412***(0.070) |

| City_rome | −0.903***(0.142) | −2.415***(0.076) | −0.557***(0.142) | −1.523***(0.076) |

| City_istanbul | .38*(0.158) | −1.173***(0.077) | .728***(0.159) | −0.809***(0.077) |

| City_london | −0.287(0.147) | −2.511***(0.083) | −0.192(0.147) | −1.581***(0.083) |

| City_newyork | −0.634***(0.110) | −0.464***(0.071) | −0.647***(0.110) | −0.312***(0.071) |

| Constant | 8.182***(0.142) | 6.304***(0.066) | 5.438***(0.142) | 4.348***(0.066) |

| LL | −8539.009 | −29,472.268 | −6254.701 | −20,939.522 |

| AIC | 17,116.831 | 58,982.725 | 12,548.215 | 41,917.233 |

| BIC | 17,208.370 | 59,102.378 | 12,639.754 | 42,036.886 |

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001; Standard errors are in parentheses.

Macro Influencers. For videos created by macro-influencers, defined as those with subscriber counts exceeding 100,000, high-arousal negative emotions such as anger and disgust significantly enhanced viewer engagement, whereas low-arousal negative emotions (fear and sadness) diminished it. Specifically, the results of the negative binomial regression analysis revealed that the use of words expressing anger substantially increased both the number of likes (β = 14.05, p < .001) and the number of comments (β = 11.83, p < .001). Similarly, expressions of disgust positively influenced the number of likes (β = 9.53, p < .001) and comments (β = 8.50, p < .001). Consequently, H1 is supported.

On the other hand, the use of words associated with fear led to a decrease in both likes (β = −9.91, p < .001) and comments (β = −6.57, p < .001). Likewise, the use of words expressing sadness also resulted in a reduction in the number of likes (β = −11.87, p < .001) and comments (β = −13.78, p < .001). Thus, H2 is supported.

Micro Influencers. In stark contrast to macro-influencers, videos created by micro-influencers show a significantly negative impact of high-arousal emotions on viewer engagement, whereas low-arousal emotions generally have a positive effect. Specifically, the use of words expressing anger lowered the number of likes (β = −5.50, p < .001) and the number of comments (β = −2.13, p < .001). Expressions of disgust also decreased the number of likes (β = −1.85, p < .001) and comments (β = −2.56, p < .001), supporting H3.

Conversely, words expressing fear led to an increase in both number of likes (β = 19.56, p < .001) and number of comments (β = 12.66, p < .001), as hypothesized. However, contrary to our prediction, sadness did not show a statistically significant influence on likes (β = −0.75, n.s.) or comments (β = −0.42, n.s.). Thus, H4 was partially supported.

Positive emotions in youtube travel contentExpressions of positive emotions by both macro and micro influencers were hypothesized to enhance engagement levels (H5). The results of the analysis partially support these hypotheses. Specifically, in videos created by macro-influencers, joy did not have an impact on the number of either likes (β = 0.36, p > .05) or comments (β = 0.19, p > .05). A significant effect was observed for surprise only on the number of comments (β = 4.75, p < .05), whereas no effect was found on the number of likes (β = 1.59, p > .05).

In videos created by micro influencers, positive emotions generally had a positive impact on user engagement. While joy-associated expressions did not affect the number of likes (β = −0.13, p > .05), they positively influenced the number of comments (β = 0.33, p < .01). Expressions of surprise had a positive impact on both the number of likes (β = 6.48, p < .001) and comments (β = 4.93, p < .001).

All other control variables, including posting period, video length, and word count, exhibited a significant positive influence on viewer engagement irrespective of the influencer type. In other words, longer posting durations, longer video lengths, and higher word counts are associated with increased likes and comments.

Discussion and implicationsThe findings offer valuable insights into the complex role of emotional expression in influencer marketing, with a particular focus on its applications in the tourism industry. This study extends the existing literature on social media engagement and influencer effectiveness by examining the impact of discrete emotions expressed by travel influencers on YouTube, with consideration given to influencer type based on the number of followers. These results contribute to several key theoretical areas in marketing and psychology, shedding light on the intricate interplay between influencer type, emotional expression, and consumer engagement.

Theoretical implicationsIn the recent literature, the interplay between emotional dynamics and influencer types on social media engagement has received significant scholarly attention, particularly regarding the ways in which different emotions affect audience interaction. The findings on emotional engagement in tourism contexts are consistent with those of broader research on consumer responses to tourism innovation (Chan et al., 2016). Intertwining the appraisal theory of emotions and the parasocial relationship theory, this study aimed primarily to identify how discrete emotional expressions influence viewer engagement, as well as the differing impacts based on influencer type. The results contribute to the literature on social media engagement and influencer marketing in three ways.

First, the findings indicate that high-arousal negative emotions (anger and disgust) have a significant positive effect on the engagement levels of macro-travel influencers, whereas low-arousal negative emotions (fear and sadness) have a negative impact on engagement levels. The appraisal theory of emotions, along with emotional contagion theory, provides a basis for understanding how high-arousal negative emotions can drive engagement, especially when propagated by macro-influencers. These influencers, with their large follower bases and perceived authority, are well-positioned to utilize such emotions because of their significant reach and the inherent intensity of the reactions that these emotions provoke. High-arousal emotions are more likely to capture attention and elicit strong responses because they are associated with perceived threats or moral violations that demand immediate attention from viewers (Lazarus, 1991; Scherer, 1984). Jin and Phua (2014) emphasize that the perceived authority and expertise of macro-influencers amplify these effects, as audiences are more likely to engage with content that appears to be informed by knowledgeable sources. However, the effectiveness of low-arousal emotions is diminished among macro-influencers because of their broad and diverse audience, which may not resonate uniformly with these emotions (Jin & Phua, 2014). This is because low-arousal emotions do not demand the same level of immediate reaction or consensus among heterogeneous groups, which limits their impact on engagement.

Second, the results for micro-influencers were the opposite of those for macro-influencers: high-arousal negative emotions negatively influenced viewer engagement, whereas low-arousal negative emotions enhanced it. Micro-influencers thrive on their perceived authenticity and close relationships with their followers, and leverage parasocial relationships (Horton & Wohl, 1956) to increase their engagement and authenticity and foster higher audience engagement compared to mega and macro-influencers (Conde & Casais, 2023). Gong and Holiday (2023) found that parasocial attributes enhance perceived authenticity, which in turn boosts engagement. Micro-influencers should, therefore, create content that resonates with their audience's emotions and experiences. For instance, sharing personal stories and struggles makes content more relatable and humanizes the influencer, thereby deepening emotional connections (Chen et al., 2024). The success of low-arousal negative emotions in enhancing engagement with micro-influencer audiences is because of their ability to evoke empathy and support. Micro-influencers who express vulnerability and authenticity through low-arousal negative emotions may foster deeper engagement by encouraging viewers to empathize with and relate to their experiences. By sharing content that shows their struggles or personal challenges, they can establish a supportive atmosphere that encourages dialogue and interaction. However, high-arousal, negative emotions may be perceived as exaggerated or inauthentic, potentially alienating followers from seeking genuine and trustworthy content. This perception is particularly relevant for micro-influencers who rely on authenticity and close relationships with their audiences to drive engagement. When micro-influencers use high-arousal negative emotions, their followers may perceive the content as manipulative or insincere, thereby undermining their credibility. Micro-influencers can maintain their credibility and foster strong connections with their audiences by expressing genuine emotions and avoiding exaggerated negativity, thereby enhancing their impact and efficacy in marketing (Yuan & Lou, 2020).

Finally, the partial support for the hypothesis that positive emotions (joy and surprise) would positively affect engagement reveals complex dynamics. The results indicate that joy significantly boosts comments for micro-influencers, while surprise increases both likes and comments. However, these effects are not statistically significant for macro-influencers. This discrepancy suggests that a greater breadth and diversity of macro-influencers’ audiences may dilute the impact of positive emotions, as a more intimate connection may be necessary to drive effective engagement. However, for micro-influencers, joy enhances relatability and viewer interaction through comments, aligning with the findings of Hsu and Lin (2020)) that emotions that foster social presence and connection significantly boost engagement. The intimate nature of the relationship between micro-influencers and their followers allows for a more profound impact of positive emotions, such as joy and surprise. Joy creates a sense of warmth and connection, encouraging followers to comment and interact with each other. Conversely, surprise captures attention and stimulates interest, proving to be a powerful tool for engaging viewers (Meyer et al., 1997).

Practical implicationsIn recent years, travel influencers on YouTube have emerged as significant and influential forces in how audiences perceive and engage in travel-related content. These influencers employ the platform's visual and interactive capabilities to create immersive experiences for viewers and inform them of travel-related decisions. The efficacy of travel content resides in its capacity to blend remarkable visuals, compelling narratives, and individual anecdotes, which collectively form stories that emotionally strike chords with audiences. Travel content on YouTube is unique in its ability to offer viewers vicarious destinations. According to Lin et al. (2024), travel content satisfies consumers’ needs for information and entertainment, significantly influencing travel intention and the likelihood of sharing electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM). This emphasizes the importance of emotional engagement in driving viewer behavior and highlights the role of travel influencers in facilitating these experiences. Influencers can foster robust emotional connections with their audiences by aligning their content with viewers’ expectations, thereby stimulating viewer engagement and sharing behaviors.

Travel influencers can leverage the emotional resonance of their posts to foster connections with followers. By tapping into the emotional appeal of their content, they can prompt engagement and interaction. Micro-influencers, in particular, excel at building close relationships with their followers by sharing authentic experiences and personal challenges. Influencers often express low-arousal negative emotions to foster empathy and support from their audiences. This approach enhances relatability and trust, which are the key elements in building loyal followings. The intimate nature of micro-influencers’ relationships with their audiences enables a more profound impact of emotional content, facilitating the cultivation of a supportive community that is more likely to engage with the content and respond to calls for action.

By contrast, macro-influencers, with their broader and varied audiences, frequently elicit strong negative emotions to capture attention and initiate discourse on important travel-related issues, including deficiencies in facilities, environmental degradation, and unethical business practices. However, it is important for them to strike a balance when handling these emotions to avoid losing the audience's trust or undermining their credibility. Although high-arousal emotions can attract initial attention, the challenge is sustaining viewer engagement without overwhelming or fatiguing the audience. This balance is critical for maintaining a credible and engaging presence.

Positive emotions such as joy and surprise are powerful tools for both micro- and macro-influencers to enhance engagement. By showcasing joyful travel experiences and unexpected discoveries, influencers can inspire and excite their audiences, fostering a sense of wonder and adventure (Cheng 2020). The ability to evoke positive emotions not only enhances the viewer's experience, but also encourages the sharing of content, thus expanding its reach and impact.

This study contributes to the growing body of knowledge on the multifaceted role of emotions in influencer marketing. The findings illustrate that the emotional manifestations of travel influencers on YouTube have a specific influence on audience participation, depending on the size of the influencer's followers. By demonstrating that different types of influencers elicit varying engagement responses based on their emotional content, this study offers theoretical and practical insights for developing more effective emotional strategies in digital marketing. These contributions not only enhance our knowledge of emotional dynamics in YouTube travel content, but also provide actionable guidelines for optimizing audience interaction with influencer-driven content.

Conclusion, limitations, and future researchBy employing advanced text-mining techniques and machine learning methods, this research advances methodological approaches for analyzing emotional content on a large scale, providing a robust understanding of how emotional dynamics shape audience behavior. These insights not only contribute to the theoretical discourse on social media marketing leveraging influencers but also offer practical guidance for marketers to consider emotional tone and influencer type when designing campaigns, as different emotions can significantly influence audience interaction.

In particular, the current research offers insights into how different types of social media influencers and distinct emotional expressions influence audience engagement in the context of YouTube travel content. The findings reveal that high-arousal negative emotions such as anger and disgust enhance engagement for macro-influencers but diminish engagement for micro-influencers, while low-arousal emotions such as fear and sadness increase engagement for micro-influencers but decrease engagement for macro-influencers. Positive emotions foster greater engagement, particularly among micro-influencers.

As with any study, there are some limitations that deserve consideration and offer potentially fruitful avenues for future research. A key limitation of this study is its reliance on text mining techniques to analyze emotional expressions in video narrations. Although SALLEE offers a comprehensive analysis of emotional content, it is primarily based on linguistic data extracted from video transcripts. This approach may fail to consider nonverbal cues such as facial expressions, gestures, and vocal tone, which play a significant role in emotional communication. Future researchers could benefit from incorporating multimodal analysis and integrating video and audio data to capture the full spectrum of emotional expressions conveyed by travel influencers.

This study focuses on discrete emotions as defined by Ekman's (1971) emotional dimensions, which include anger, disgust, fear, sadness, joy, and surprise. Although these emotions provide a useful framework, the discrete emotions that may influence engagement in different ways warrant further investigation. Further exploration of emotional arousal could offer deeper insight into how varying levels of intensity in emotional expressions influence viewer engagement. Examining the intensity of emotional expressions can yield invaluable insights into the viewers’ responses and interaction levels. Future researchers could extend the emotional framework to encompass a more detailed examination of arousal and its impact on engagement, thereby facilitating a comprehensive understanding of emotional dynamics in influencer marketing.

In this study, influencer classification used a follower-based criterion from previous research (Campbell & Farrell, 2020); however, future studies may benefit from incorporating varying market contexts. For example, Conde and Casais (2023) note that influencer classification based on follower counts can differ depending on market size and conditions, particularly in smaller markets. While their findings provide insights into the Portuguese market, our study focuses on the global travel industry, in which content is produced and consumed primarily in a global English-speaking context. Therefore, we adopted Campbell and Farrell's approach for broader relevance. Nevertheless, as Conde and Casais suggest, local market conditions, may accommodate alternative classification frameworks especially in non-English-speaking or less-globalized regions. Future research on how these classifications may be adapted across different regions and industries could shed light on our understanding of influencer classification in diverse contexts.

Another limitation lies in the scope of this study, which focused exclusively on YouTube travel influencers. Although YouTube is a major influencer marketing platform, other social media platforms, including Instagram, TikTok, and Facebook, may also influence travel decisions considerably. Exploring cross-platform dynamics and comparing emotional engagement across social media channels can provide valuable insights into how platform-specific features influence influencer effectiveness.

This study measures engagement primarily through likes and comments, which are valuable indicators of viewer interaction but may not fully capture the depth of engagement or the nuances of audience perception. Future researchers could incorporate additional metrics such as view counts and shares to provide a comprehensive picture of audience engagement. Setting thresholds for these engagement measures could help identify the points at which these metrics reflect meaningful interactions and influences.

While this study examines how emotional expressions impact viewer engagement, it does not directly measure other key factors, such as influencer credibility, authenticity, and engagement strategies. Although these factors are important, they are inherently difficult to quantify in the context of big data. Future researchers could employ alternative methodologies, such as experimental designs or mixed-method approaches, to examine how these elements interact with emotional expressions to enhance engagement.

CRediT authorship contribution statementJinyoung Jinnie Yoo: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Heejin Kim: Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis. Sungchul Choi: Data curation.