The strict rational paradigm of neoclassical economic theory has resulted in limited exploration of emotions in managerial decision-making processes. This study attempts to address this gap by examining how emotions influence efficient managerial decision-making, generating a modern perspective for organizational theory beyond the existing theoretical paradigm. The concept of managerial decision-making is approached through three dependent variables: strategic planning, innovative crisis management, and pragmatism. This study analyzed the responses of 151 managers of small- and medium-sized firms in Greece collected during field research in 2023. Emotions are perceived as unique information that interacts with other factors, such as the conscious evaluation of inputs. The analysis of emotions was based on a modified understanding of the anthropological term of emotional culture. The findings demonstrate that emotional culture contributes to managerial decision-making. Influential variables included basic emotions, emotions that communicate motives, cultural values, fast and slow thinking, and demographics. These variables highlight the interaction of pure emotional and rational factors in managerial decision-making. This study provides insights into how “human-related” traits contribute to or affect decision-making processes. This interdisciplinary perspective has both micro- and macro-level implications. At the micro level, the study explores strategic management, managerial skills for effective decision-making—especially considering the rise of artificial intelligence—and modern perspectives of organizational theory based on behavioral economics. At the macro level, it offers insights into cumulative behavioral expressions and how emotion analysis could be used to understand cultures and stereotypes within societies. The study has implications for the relationship between policymaking and production structure.

Managers make decisions (Vroom, 1973) that rely on personal judgment (Kozioł-Nadolna & Beyer, 2021). This means that their personal, emotional, and cognitive characteristics affect their management styles and effectiveness (Vroom, 1973). Decisions are based on conscious rationality, subconscious emotional influences, and instincts, especially in familiar situations (Tohidi & Jabbari, 2012). Emotions inform managerial decision-making. However, due to the influence of neoclassical theory, which assumes that decision-making is purely rational, the role of emotions in managerial decision-making has been underexplored. Given the limited research on the subject, there is a need to uncover the “reason behind unreason” (Simon, 1987).

The primary objective of this study was to explore how and to what extent emotionally related factors contribute to managerial decision-making. Managerial decision-making is approached through three dependent variables representing the broad and complex nature of decision-making mechanisms: (i) strategic planning, (ii) innovative crisis management, and (iii) pragmatism.

An exploratory quantitative study of efficient small- and medium-sized firms (employing at least ten individuals) in Greece in 2023 was conducted. The research uses financial turnover from 2020 to 2022 to determine firm efficiency. Selecting well-established firms with good financial turnover served as a criterion for efficient management and decision-making.

For data collection, the field research was conducted by a Greek survey bureau (Metron Analysis S.A.), which was certified for its quality. The bureau approached 151 managerial executives and conducted in-person interviews using a structured questionnaire designed to capture emotions and other behavioral factors. For each dependent variable, the statistical analysis utilized machine learning techniques in the R programming language. A least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) model was applied (Tibshirani, 1996) for the selection and shrinkage of parameters. Linear regressions were then performed for the nonzero estimations of the LASSO model to analyze the explanatory relationship between the dependent and independent variables.

Machine learning techniques for the social sciences identify generalizable patterns and complex structures that are unspecified in advance (Mullainathan & Spiess, 2017). Additionally, the LASSO method and machine learning are commonly used in economics and social sciences because they provide high-performance models when multiple predictors are present (Mullainathan & Spiess, 2017).

The present study perceives emotions as particular types of information that interact with other factors, such as the conscious evaluation of inputs. The analysis of emotions is based on a modified understanding of the anthropological term “emotional culture” (Thoits, 1989). The findings demonstrate that emotional culture contributes to managerial decision-making. Influential variables include basic emotions, emotions that communicate motives, cultural values, fast and slow thinking, and demographics, which highlight the interaction of purely emotional and rational factors in managerial decision-making.

Understanding how emotions influence managerial decision-making is important, given the increasing complexity of available information. Societies are entering an era of rapid and transformative socioeconomic conditions, requiring interdisciplinary perspectives in management decisions, especially in corporations. This is because quality information is either unavailable or private.

The present study investigates how “human-related” traits, which may operate silently, influence decision-making processes. This interdisciplinary approach has both micro- and macro-level implications. At the micro level, the study explores strategic management, managerial skill portfolios for effective decision-making—especially with the rise of artificial intelligence—and modern perspectives of organizational theory based on behavioral economics. These insights have practical implications, guiding the design of a training framework for managerial decision-making. They explain how integrating emotions in formal analysis and communicating the structure of decision-making mechanisms can help managers make better decisions.

At the macro level, the study provides insight into cumulative behavioral expressions and how emotion analysis could be leveraged to understand cultures and stereotypes within societies. This has implications for the relationship between policymaking and production structure. Assuming that Greece's macroeconomic context shapes the nature and structure of managerial decision-making in the sample, policymakers can promote proactive and innovative decision-making by designing policies and reforms to address the country's economic pathogenies. This includes providing more opportunities for strengthening its regulatory framework and transparency in political decision-making.

This paper is structured as follows. Literature regarding the nature of emotions and their link to managerial decision-making are examined in Section 2. This theoretical analysis outlines the conceptual framework of the study. Section 3 deals with statistical analysis and the results are interpreted in Section 4. Section 5 presents the synthesis and subsequent discussion of the theoretical and practical consequences of these findings, as well as limitations and future research directions. Section 6 concludes the study.

Theoretical backgroundAcross various fields (philosophy, science, and art), a fundamental trait of human existence is the expression, understanding, and interpretation of emotions, which comprise an indispensable aspect of human existence. For a comprehensive sociological, organizational, and scientific understanding, emotions must be analyzed in terms of both their nature and their connection to managerial decision-making. Therefore, this section examines various theories about emotions, with particular emphasis on anthropology, developmental and social psychology, and organizational theory, to provide a theoretical framework for analysis. A questionnaire was developed based on this theoretical framework.

A very brief introduction to emotionsEmotional classification is complex and varies depending on the research perspective (Bulagang et al., 2020). According to the discrete classification of emotions, six primary or basic emotions are categorized as either positive or negative (Ekman, 1989). Happiness and surprise were classified as positive, whereas sadness, fear, anger, and disgust were classified as negative. Emotions can be classified as primary (similar to basic emotions) or secondary (being linked to mental images and basic emotions; Bulagang et al., 2020). An accepted definition of emotions involves their association with pleasant or unpleasant psychological states (Ekman, 1989).

This neurological approach to emotion emphasizes an organism's relationship with its environment (Adolphs & Heberlein, 2002). In neuroscience, emotions are brief responses formed by exposure to certain stimuli and are expressed through psychic and somatic means (LaBar, 2015). Before an emotion's expression, several information processing stages occur, including the assessment of sensory input regarding its pleasure value, the generation of an expressive response, and the generation of a subjective emotional state (LaBar, 2015).

Thus, an emotion's defining features concern (i) the recognition and evaluation of emotionally significant stimuli, (ii) the endocrine, autonomous, and motor (kinetic) changes in response to the emotion, and (iii) the conscious experience of the emotion (Adolphs & Heberlein, 2002). Importantly, the experience, recognition, and expression of emotions often overlap (Adolphs & Heberlein, 2002).

The evolutionary theory of emotions, which influenced Ekman (1989), suggests that emotions are not merely responses to external stimuli but also serve specific evolutionary functions. This perspective was derived from Darwin (1872)), who focused on the continuity of emotional expression between humans and animals through certain universally recognized emotions, including facial expressions like anger, pain, and rage. Darwin argued that certain gestures expressing emotions (like affirmation and approval) are culture-specific conventions influenced by the human social environment (Darwin, 1872). Emotions are endogenous processes with evolutionary purposes such as facilitating communication, meaning that they possess the aspect of continuity (Darwin, 1872).

Emotions also have social dimensions (LaBar, 2015). Social emotions are complex and relate to the concepts of personal and social morality, which define models of acceptable behavior within societies and institutions. They may vary, to a greater or lesser extent, depending on the person, the population, and the geographical area. These differences could be attributed to different identity traits (gender, education, and age), socioeconomic characteristics (rate of economic development and technological advancement), and broader social contexts.

For these reasons, Matakias (2005) further classified emotions based on the human species’ innate needs as (i) emotions of the ego—referring to the self's being, such as the pleasant or unpleasant view a person holds about themselves—arising from awareness of the self; (ii) emotions of the thou, which refer to the individual's intimate environment and include affection, friendship, indifference, and envy; and (iii) social emotions, referring to collective externalizations, such as patriotism and pride. Emotions are evolutionary mechanisms that inhibit or encourage human actions that are universal or affected by social conditions (Tannenbaum, 1950).

Emotions can serve as the defining forces of social balance. For example, Pareto distinguishes between (i) societies in which emotions operate autonomously and (ii) societies that are defined by reasoning and experimental syllogism (Parsons, 1968). The emotions and conditions of the former define non-normative factors for action. In contrast, the collective goals of the latter shape the normative aspects of action. Human society falls between these two categories, which are mirrored in managerial decision-making.

In the sociological consideration of emotions, a distinction is made between the microeconomic (socio-psychosocial dimension) and the macroeconomic (structural and social dimension) levels (Thoits, 1989). Human actions “bridge” the microeconomic and macroeconomic dimensions as they are shaped by personal and emotional needs; thus, they are framed by the values and stereotypes of society. Macroeconomic dimensions are the result of the creation of an emotional culture, which is primarily formed through interaction and learning—a focus of anthropological study (Thoits, 1989). Emotional culture and the mapping of cultural background affect individuals’ experiences and behaviors, revealing certain microeconomic tensions that can influence the development of a society or organization (Thoits, 1989).

In the present study, emotional culture was segmented to reveal distinct levels of significance and influence on decision-making processes, as illustrated in Fig. 1. These layers of emotional culture are relevant to the aforementioned emotion theories.

Managerial decision-making and emotionsManagerial decision-making concerns evaluating information inside and outside the business or organization and leveraging expertise, knowledge, interconnected thinking, and critical thinking (Eilon, 1969). Decision-making is based on a person's values, culture, and beliefs (Simon, 1977); it involves the interplay of power, behavioral factors, and using logical reasoning (U et al., 2021).

When making a business decision, (i) the problem to be solved is not always clear, necessitating a search for potential threats; (ii) the alternatives are not always available, meaning that searching for alternatives is critical to the decision process; (iii) the information on the consequences of each alternative is seldom given, requiring an exploration of possible outcomes; and (iv) choosing among alternatives involves using multidimensional criteria beyond the single-profit criterion, such as making a positive impact (Cyert et al., 1956). In the best-case scenario, managers must choose between various alternatives or explore new problem-solving avenues (Kozioł-Nadolna & Beyer, 2021).

The rational approach to decision-making suggests that it results from conscious processes that shape behavior (Tannenbaum, 1950). Hence, managerial behavior and planning originate from analytical and rational thought rather than from preconceived notions (Citroen, 2011). In conventional management literature, cognition and rationality are the key characteristics of a decision-maker (Simon, 1957a), while emotions are seen as irrelevant to the process (Damasio, 1994). Rational decision-making requires a closed normative system in which individuals align with tactical expectations and have access to all available information. In this context, firms and organizations are viewed as black boxes, and managers are considered undifferentiated.

Some pioneering studies have questioned the concept of pure rationality. These include Simon's (1957b) introduction of bounded rationality, recognizing the limitations of human decision-making; the concepts of moral hazard and adverse selection (Akerlof, 1970); opportunism in transactions (Williamson, 1975); and Kahneman and Tversky (1979), who found that individuals make decisions based on heuristics and the likelihood of uncertain events.

Kahneman and Tversky (1979) suggested that individuals display myopic behavior in times of crisis and apply heuristic principles for decision-making based on the availability of past individual or shared experiences, memories, and the perceived negativity of potential outcomes. Additionally, managerial decision-making encompasses the continuous use of past experiences to make better future decisions (U et al., 2021). While the systematic utilization of heuristic rules leads to systematic errors and biases, heuristics are an important part of learning and problem-solving. When applied correctly, they simplify problems and enable quick responses (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979).

Deviations from the rational behavioral paradigm include risk aversion and irrationality, which result from inherent asymmetry in the preference structure (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). Risk aversion suggests that the absolute subjective value of a particular loss is greater than the absolute subjective value of an equivalent gain (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). Interestingly, risk aversion increases when individuals make decisions for others rather than themselves (Zhang et al., 2017). This is relevant for managers, firms, or organizations. For example, Sjöberg (2003) found that intuitive decision-making is favored when individuals make personal decisions in nonprofessional roles, whereas in professional roles, they tend to favor rational and pragmatic approaches.

These studies and approaches help in understanding the limitations of the rational behavioral paradigm but do not fully explore pure behavioral elements because they remain within the neoclassical framework. Individuals’ unique characteristics, experiences, and social environments influence their decision-making processes, making them unique (Langley et al., 1995). Extra-rational processes go beyond conscious thought and play a critical role in policymaking (Langley et al., 1995) and strategic management (Citroen, 2011). Given the gaps in rational theories, an alternative perspective emphasizes behavioral factors and subconscious processes, such as emotions (Sayegh et al., 2004). This viewpoint has led to a major dichotomy in managerial decision-making theories regarding intuitive and emotionally informed decision-making versus analytical decision-making (Sjöberg, 2003).

The idea that decision-making is derived from knowledge, experience, and emotion takes precedence over pure rationality (Gigalová, 2017). This means that, beyond cognitive abilities, managers consider biases based on the overall environment of the firm and their personal experiences (Lovallo & Sibony, 2010). For example, people from diverse cultures may differ in their expectations, choices, and priorities (Shah et al., 2018). The social context of an organization is important because managers must make, among others, complex, uncertain, and impactful social decisions (Damasio, 1994). Hence, incorporating cultural factors and social emotions into the present analysis is necessary and justifies the external layer of emotional culture (Fig. 1).

Managers do not behave identically, as emotions and other complexities influence their decision-making (Sjöberg, 2003). Given the association between management and social decisions, understanding how emotions affect such processes is essential for effective managerial decision-making (Sayegh et al., 2004). This is because, under certain circumstances, emotions can serve as a beneficial guide for action (Lerner et al., 2015).

Emotions and emotional responses during decision-making provide structure and meaning to experiences and situations, even unconsciously (Eberhardt et al., 2019; Sayegh et al., 2004). According to Lerner et al. (2015), emotions affect decisions through changes in context, depth of thought, and implicit goals. Furthermore, emotions are not necessarily heuristic because they trigger systematic thought when activated (Lerner et al., 2015). However, the desire to experience positive emotions after making certain decisions can generate cognitive bias, particularly regarding important decisions (Gosling et al., 2020).

In decision-making, emotions serve communicative functions and operate as direct or indirect information signals available to both the expresser and the observer, who may witness or learn about these emotional displays (Hareli & Hess, 2012). While this information is situational and context-dependent, it also extends beyond any specific situation because it accumulates as experience (Hareli & Hess, 2012). Overall, managers’ psychological frameworks shape their decision-making styles and processes (Wallace & Rijamampianina, 2005).

For instance, reduced negative emotions produce better financial decisions (Eberhardt et al., 2019), and emotional regulation can enhance managerial social capital (Huy & Zott, 2019). Emotions can act as stable personality traits in the context of strategic managerial decisions and are critical during strategic changes (Treffers et al., 2020). Different emotional states affect managerial decision-making differently (Koporcic et al., 2020). Therefore, emotional intelligence and self-awareness are valuable traits for managers because they enable adaptability and the ability to analyze various viewpoints (Khalisah, 2023).

Another aspect of emotional decision-making concerns the role of intuition, which involves learned behavior sequences. According to Simon (1987), intuition ensembles a chess master's ability to recognize patterns. Intuition improves with experience and involves a rapid and silent procedure where problem recognition and matching to a suitable memory result in the problem's resolution (Simon, 1987). Emotions may undermine intuitive decision-making (Simon, 1987). For instance, Bachkirov (2015) found that happiness and anger can cause managers to overlook decision-relevant information, while fear activates detailed processes. Thus, emotions could lead to delaying or rushing decisions based on anticipated emotional outcomes rather than information processing (Koporcic et al., 2020).

To explain the aforementioned asymmetries, dual-process theories provide an architecture for the interaction between intuitive – emotional (Type 1) and deliberate (Type 2) thinking (Thompson, 2014). According to Kahneman (2012), the Type 1 system is fast, intuitive, and automatic; it uses heuristics to reduce the time spent on cognitive processes and draws from emotions. A Type 1 thinking system may result in biases, while the Type 2 system is slower, more deliberative, and rational.

Type 1 processes are executed faster than Type 2, forming the basis of an initial response that may or may not be altered by subsequent deliberation (Thompson, 2014). Both types of thinking affect how individuals process and manage crucial information for decision-making. Consequently, if someone's primary thinking is Type 1, they will make quicker decisions, and vice versa if they are Type 2. Nonetheless, both types of thinking are important and often inseparable in terms of establishing boundary conditions (Thompson, 2014).

This study investigates whether a combination of Type 1 and Type 2 thinking occurs during decision-making and what behavioral and emotional qualities are involved. The study dissects emotion culture (Fig. 1) and directly or indirectly associates its layers with Type 1 or Type 2 thinking. Type 1 thinking is more primitive-oriented, aligning more with basic emotions (the core of emotional culture). In contrast, Type 2 thinking arises from complexity and cognitive development and aligns with the intermediate and external layers of emotional culture. Due to its universal significance, the external layer of emotional culture, related to social values and norms, is important for both thinking types due to its transformative impact on macro-conditions.

Explaining how emotions affect managerial decision-making is valuable (Treffers et al., 2020). It could help with the development of a learning framework for managers to understand emotions as individual abilities and better communicate them in the course of their decision-making.

Research methodsResearch questionThis study aims to underscore the relationship between emotional factors and managerial decision-making. Managerial decision-making is examined through three dependent variables: (i) strategic planning, (ii) innovative crisis management, and (iii) pragmatism.

Strategic planning involves preparing for future problems and challenges using forward-looking policies, which is crucial for strategic decision-making and long-term business success (Wallace & Rijamampianina, 2005). Planning for the future is critical to the growth and resilience of an organization, facilitating managerial decision-making and fostering efficiency (Fashola et al., 2016). This variable was assessed by analyzing the responses of those who identified with the statement: “I tend to focus on preparing for the future.”

Innovative crisis management relates to a manager's tendency to rely on innovation rather than accumulated knowledge during a crisis (Sayegh et al., 2004). This is an important aspect of managerial decision-making in challenging times, as crises are often significant, unfamiliar, and unusual situations that require innovation (Sharma et al., 2022). This variable was assessed by analyzing the responses of those who identified with the statement: “In times of crisis, I tend to find solutions out of the box rather than relying on accumulated knowledge.”

Pragmatism is viewed as a decision-making style that relies on formal analysis rather than intuition, indicating a more considered approach (Sjöberg, 2003). This variable was assessed by analyzing the responses of those who identified with the statement: “I believe that I am more pragmatic than intuitive when making decisions.”

DataThe data were obtained from field research conducted in Greece in 2023. To ensure transparency and accuracy, data collection was handled by Metron Analysis S.A., a member of the European Society for Opinion and Market Research and the Market Research and Public Opinion Companies Association. Data were gathered through a structured questionnaire and in-person interviews. This approach enabled the measurement of emotional and other behavioral factors using self-reported responses (Schouteten, 2021), where the respondents categorized themselves on a given scale for different questions. Three researchers and one supervisor managed the data collection. Furthermore, 20 % of the interviews were verified by re-contacting the respondents, and 100 % were successfully checked electronically.

The sample choice covered managerial executives from Greece who were employed at firms with a minimum of 10 employees and demonstrated good financial turnover. The sample was chosen from the available data from the ICAP list. The sample comprised 151 managerial executives from small and medium-sized firms. The demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1, and the descriptive statistics of the sample are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Demographic characteristics of the sample.

| Gender | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 71 | 47 % |

| Male | 80 | 53 % |

| Age | Frequency | Percent (%) |

| Up to 34 | 13 | 9 % |

| 35–44 | 44 | 29 % |

| 45–54 | 34 | 36 % |

| 55+ | 41 | 26 % |

| Education | Frequency | Percent (%) |

| High school graduate | 7 | 5 % |

| Bachelor's or equivalent degree | 78 | 52 % |

| Master's or doctorate or equivalent degree | 66 | 43 % |

| Sector of economic activity | Frequency | Percent (%) |

| Manufacturing industry | 60 | 41 % |

| Retail | 49 | 32 % |

| Services | 41 | 27 % |

| Managerial position | Frequency | Percent (%) |

| Chief Executive Officer or Chief Financial Officer | 57 | 39 % |

| Chief Operating Officer | 22 | 14 % |

| Chief Marketing Officer | 34 | 22 % |

| Chief Human Resources Officer | 38 | 25 % |

| Years in a managerial position | Frequency | Percent (%) |

| Up to 5 | 27 | 18 % |

| 6–10 | 35 | 23 % |

| 11–15 | 30 | 20 % |

| 16–20 | 18 | 11 % |

| 21+ | 42 | 28 % |

| Individuals employed in the firm | Frequency | Percent (%) |

| 10–50 | 32 | 21 % |

| 51–250 | 77 | 51 % |

| 251+ | 42 | 28 % |

| Average financial turnover in the last three years (in euros) | ||

| 2020 | 62,636,794.64 | |

| 2021 | 90,624,985.03 | |

| 2022 | 75,483,250.89 | |

The generated survey questionnaire formed the basis for creating the variables used in this study. The aim of the survey questionnaire was to trace a range of emotions based on the emotion culture visualization in Fig. 1. Other emotional factors related to decision-making were categorized based on the thinking type (Type 1 or 2) to develop an evolutionary approach from an information-processing perspective (Al-Shawaf et al., 2016). The survey questionnaire is presented in detail in Appendix Table 1.

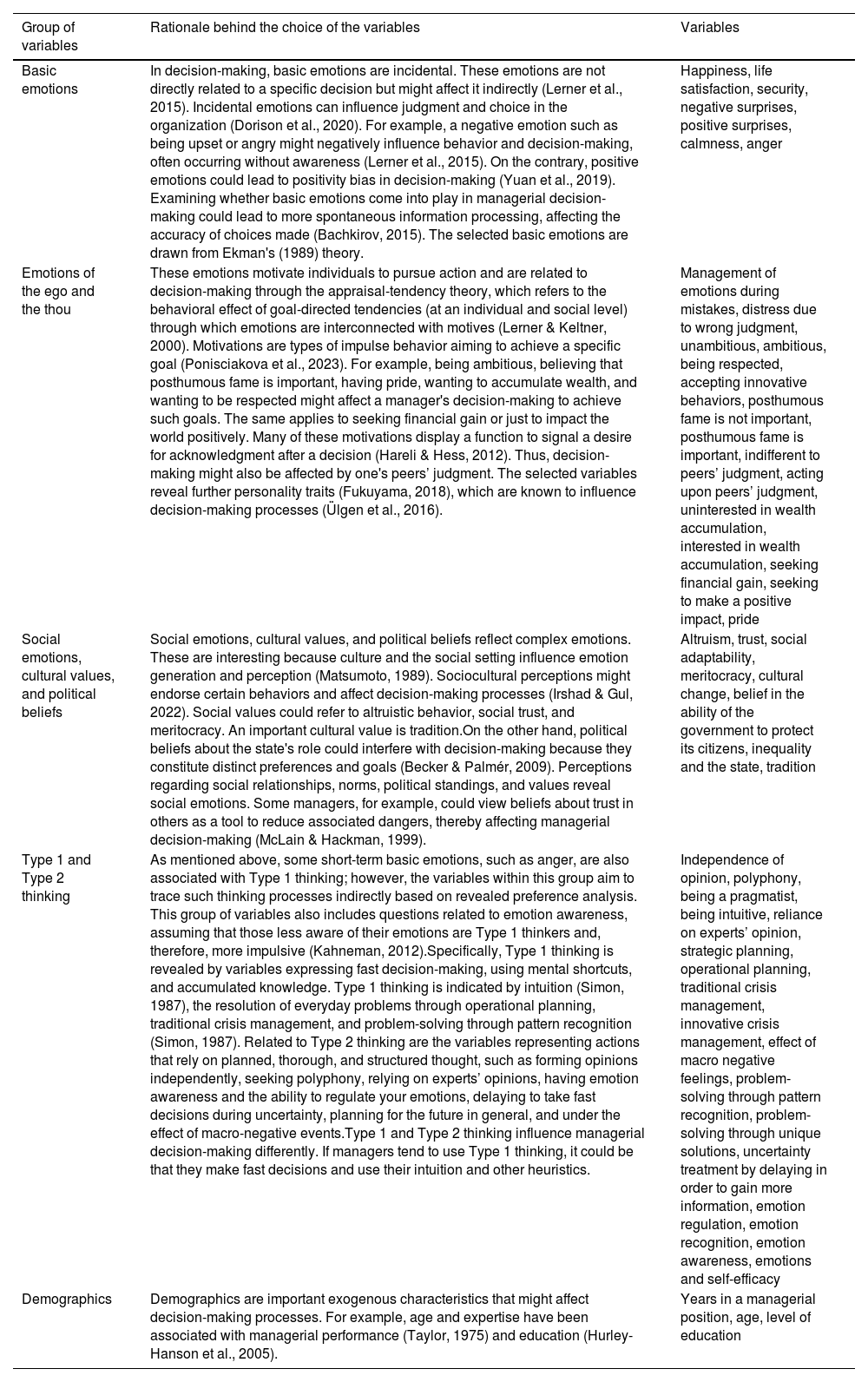

In some instances, polarized responses precipitated the creation of binary variables. As a result, the present study used 50 variables, including the binary ones. The names and categorizations of the variables, as well as the rationale behind their choices, are presented in Table 2.

Presentation of the variables used.

| Group of variables | Rationale behind the choice of the variables | Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Basic emotions | In decision-making, basic emotions are incidental. These emotions are not directly related to a specific decision but might affect it indirectly (Lerner et al., 2015). Incidental emotions can influence judgment and choice in the organization (Dorison et al., 2020). For example, a negative emotion such as being upset or angry might negatively influence behavior and decision-making, often occurring without awareness (Lerner et al., 2015). On the contrary, positive emotions could lead to positivity bias in decision-making (Yuan et al., 2019). Examining whether basic emotions come into play in managerial decision-making could lead to more spontaneous information processing, affecting the accuracy of choices made (Bachkirov, 2015). The selected basic emotions are drawn from Ekman's (1989) theory. | Happiness, life satisfaction, security, negative surprises, positive surprises, calmness, anger |

| Emotions of the ego and the thou | These emotions motivate individuals to pursue action and are related to decision-making through the appraisal-tendency theory, which refers to the behavioral effect of goal-directed tendencies (at an individual and social level) through which emotions are interconnected with motives (Lerner & Keltner, 2000). Motivations are types of impulse behavior aiming to achieve a specific goal (Ponisciakova et al., 2023). For example, being ambitious, believing that posthumous fame is important, having pride, wanting to accumulate wealth, and wanting to be respected might affect a manager's decision-making to achieve such goals. The same applies to seeking financial gain or just to impact the world positively. Many of these motivations display a function to signal a desire for acknowledgment after a decision (Hareli & Hess, 2012). Thus, decision-making might also be affected by one's peers’ judgment. The selected variables reveal further personality traits (Fukuyama, 2018), which are known to influence decision-making processes (Ülgen et al., 2016). | Management of emotions during mistakes, distress due to wrong judgment, unambitious, ambitious, being respected, accepting innovative behaviors, posthumous fame is not important, posthumous fame is important, indifferent to peers’ judgment, acting upon peers’ judgment, uninterested in wealth accumulation, interested in wealth accumulation, seeking financial gain, seeking to make a positive impact, pride |

| Social emotions, cultural values, and political beliefs | Social emotions, cultural values, and political beliefs reflect complex emotions. These are interesting because culture and the social setting influence emotion generation and perception (Matsumoto, 1989). Sociocultural perceptions might endorse certain behaviors and affect decision-making processes (Irshad & Gul, 2022). Social values could refer to altruistic behavior, social trust, and meritocracy. An important cultural value is tradition.On the other hand, political beliefs about the state's role could interfere with decision-making because they constitute distinct preferences and goals (Becker & Palmér, 2009). Perceptions regarding social relationships, norms, political standings, and values reveal social emotions. Some managers, for example, could view beliefs about trust in others as a tool to reduce associated dangers, thereby affecting managerial decision-making (McLain & Hackman, 1999). | Altruism, trust, social adaptability, meritocracy, cultural change, belief in the ability of the government to protect its citizens, inequality and the state, tradition |

| Type 1 and Type 2 thinking | As mentioned above, some short-term basic emotions, such as anger, are also associated with Type 1 thinking; however, the variables within this group aim to trace such thinking processes indirectly based on revealed preference analysis. This group of variables also includes questions related to emotion awareness, assuming that those less aware of their emotions are Type 1 thinkers and, therefore, more impulsive (Kahneman, 2012).Specifically, Type 1 thinking is revealed by variables expressing fast decision-making, using mental shortcuts, and accumulated knowledge. Type 1 thinking is indicated by intuition (Simon, 1987), the resolution of everyday problems through operational planning, traditional crisis management, and problem-solving through pattern recognition (Simon, 1987). Related to Type 2 thinking are the variables representing actions that rely on planned, thorough, and structured thought, such as forming opinions independently, seeking polyphony, relying on experts’ opinions, having emotion awareness and the ability to regulate your emotions, delaying to take fast decisions during uncertainty, planning for the future in general, and under the effect of macro-negative events.Type 1 and Type 2 thinking influence managerial decision-making differently. If managers tend to use Type 1 thinking, it could be that they make fast decisions and use their intuition and other heuristics. | Independence of opinion, polyphony, being a pragmatist, being intuitive, reliance on experts’ opinion, strategic planning, operational planning, traditional crisis management, innovative crisis management, effect of macro negative feelings, problem-solving through pattern recognition, problem-solving through unique solutions, uncertainty treatment by delaying in order to gain more information, emotion regulation, emotion recognition, emotion awareness, emotions and self-efficacy |

| Demographics | Demographics are important exogenous characteristics that might affect decision-making processes. For example, age and expertise have been associated with managerial performance (Taylor, 1975) and education (Hurley-Hanson et al., 2005). | Years in a managerial position, age, level of education |

Statistical analysis was conducted using machine-learning techniques in the R programming language. Machine learning offers tools and structures for acquiring information from data (Mendonça et al., 2024) and is expected to drive new discoveries in social research (Lundberg et al., 2022). It has been applied to both large and small datasets to uncover new concepts, measure their prevalence, assess causal effects, and make predictions (Grimmer et al., 2021). Machine learning provides an essential methodological connection between theory, data collection, and econometric analysis by expanding analytical abilities by eliminating errors and discovering new relationships (Camerer, 2019). The analysis in use utilized the steps described below. Each stage was executed separately for the three dependent variables. These variables were used exclusively as dependent variables and were excluded from the other models.

Step 1. Data preprocessing

Data preprocessing is a basic and primary step for converting raw data into useful information in machine-learning data analysis approaches (Alexandropoulos et al., 2019). Data preprocessing included data cleansing (or scrubbing), transformation, and normalization (Kotsiantis et al., 2006). Data cleansing eliminates data errors and inconsistencies. Subsequently, binary variables were created wherever response polarization occurred. This was necessary, given that certain questions in the survey referenced opposing situations; that is, if a respondent was angry, they could not be calm at the same time. The creation of binary variables simplified the analysis, facilitated the statistical treatment of categorical variables, and strengthened the transparency and comparability of the data. The preprocessing stage of the data concluded with data transformation and normalization. These processes ensured that all data had similar magnitudes, minimizing potential biases, and improving the accuracy and efficiency of subsequent statistical analyses.

Step 2. Feature selection using LASSO

The LASSO method was chosen for feature selection due to its compatibility with machine-learning statistical approaches (Camerer, 2019; Mullainathan & Spiess, 2017). LASSO shrinks some coefficients to zero, performing feature elimination, which is essential for model simplicity and avoiding overfitting (Tibshirani, 1996). This regularized linear regression defines a continuous shrinking operation that can produce coefficients that are exactly zero, retaining the features of both subset selection and ridge regression (Tibshirani, 1996).

In the LASSO, an L1 penalty minimizes the magnitude of all coefficients and allows some coefficients to be minimized to zero, thereby eliminating the predictor from the model. Following data preprocessing, the LASSO regression parameters were selected based on the coefficients and values of the L1 parameters.

Step 3. Training the LASSO regression model

The accuracy of each possible lambda (λ) value was considered to determine the tuning parameter λ of the model and minimize the mean square error via predictive analytics. The dataset was divided into training and testing sets to estimate the LASSO testing error. LASSO was fitted to the training dataset, and possible λ values were used to predict the test data. The optimal λ value yielded the lowest mean square error.

Step 4. Fitting the LASSO regression model to the full dataset

Once the best λ was selected to predict the test data, the LASSO model was fitted to the full dataset (final model). The LASSO coefficients were selected through cross-validation.

Step 5. Analysis

Using the optimum value for the parameter λ, the final LASSO model was analyzed to produce the estimations for its coefficients (the optimum λ values are provided in the Appendix section for each model). After choosing the significant nonzero estimations for the model, a linear regression was performed to analyze the relationship between the dependent and independent variables.

Step 6. Robustness tests for the final models

Multicollinearity was tested using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for each independent variable and for homoscedasticity using the Breusch-Pagan test. All generated models were found to be robust.

ResultsStrategic planningTable 3 shows the regression results using strategic planning as the dependent variable.

Regression analysis for strategic planning.

| Variable | Estimate | t-value | p-value | VIF test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic emotions | ||||

| Negative surprises | 0.81981*** | 3.482 | 0.000845 | 1.314578 |

| (0.23546) | ||||

| Emotions of the ego and the thou | ||||

| Seeking financial gain | 0.60256* | 2.399 | 0.019013 | 1.138528 |

| (0.25121) | ||||

| Accepting innovative behaviors | 0.17462 (.) | 1.724 | 0.089001 | 1.381188 |

| (0.10131) | ||||

| Posthumous fame is not important | 0.4525 (.) | 1.939 | 0.056374 | 1.532834 |

| (0.23337) | ||||

| Pride | 0.06712 | 0.67 | 0.504716 | 1.348865 |

| (0.10012) | ||||

| Unambitious | 0.06556 | 0.229 | 0.819518 | 1.478609 |

| (0.28628) | ||||

| Indifferent to peers’ judgment | −0.26013 | −1.326 | 0.189049 | 1.301851 |

| (0.19621) | ||||

| Uninterested in wealth accumulation | 0.11362 | 0.558 | 0.578233 | 1.297214 |

| (0.20345) | ||||

| Social emotions, cultural values, and political beliefs | ||||

| Meritocracy | −0.15517 | −1.562 | 0.12263 | 1.32817 |

| (0.09935) | ||||

| Cultural change | −0.07646 | −0.762 | 0.448606 | 1.355438 |

| (0.10036) | ||||

| Type 2 thinking | ||||

| Polyphony | 0.24913* | 2.503 | 0.014542 | 1.332885 |

| (0.09952) | ||||

| Emotions and self-efficacy | 0.23998* | 2.557 | 0.01264 | 1.185408 |

| (0.09386) | ||||

| Effect of macro negative feelings | 0.18071 (.) | 1.852 | 0.068046 | 1.281044 |

| (0.09757) | ||||

| Emotion recognition | 0.14216 | 1.463 | 0.147805 | 1.270854 |

| (0.09718) | ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 0.11564 | 1.221 | 0.225862 | 1.206268 |

| (0.09468) | ||||

| R2 = 0.4575 | R2adj = 0.3461 | |||

| The Breusch-Pagan test for homoskedasticity indicated no heteroskedasticity in the model. The p-value is 0.4056, which is greater than 0.05. | ||||

| No. observations: 73 | ||||

Notes: Standard errors are reported in parentheses. The symbol (.) indicated significance at p < 0.1 level. * denotes significance at p < 0.05. *** denotes significance at p < 0.001. VIF analysis indicated no significant multicollinearity between the variables since they took values below the threshold of 5. Thus, all variables provide unique information.

Emotional factors influenced strategic planning by approximately 35 %. The variables affecting strategic planning belong to the basic emotions, ego and thou emotions, and Type 2 thinking categories.

The variable denoting negative surprises in life exerted the most significant influence. In most cases, negative surprises refute expectations and affect thinking about the future (Simandan, 2020). The positive relationship between negative surprises and a forward-looking vision could be attributed to the need for prospection to anticipate future challenges. This conjecture is also derived from the fact that large-scale negative events motivate managers to reconsider future strategies within the firm.

Seeking financial gain affects strategic planning positively. One of the main drivers of foresight practices and strategic planning is improving firm performance and achieving financial goals (Rohrbeck & Kum, 2018). Managers’ tendencies to plan for future challenges are not guided by their personal aspirations. Accepting innovative behaviors within a firm plays a small positive role in strategic planning, even when they undermine a manager's authority. Innovation is crucial for the future of an organization and helps to anticipate future challenges (Tohidi & Jabbari, 2012).

Polyphony is significant in strategic planning because the future is fluid. For managers, fostering polyphony within an organization promotes collective dialog and increases awareness and attention to strategic issues (Morton, 2023). Finally, acknowledging that one's feelings might affect professional performance positively motivates strategic planning. This relationship may exist because self-regulators tend to think strategically (Wallace & Rijamampianina, 2005), likely because they understand the potential negative impact of acting upon strong emotions.

Innovative crisis managementTable 4 displays the regression results using innovative crisis management as the dependent variable.

Regression analysis for innovative crisis management.

| Variable | Estimate | t-value | p-value | VIF test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic emotions | |||||

| Negative surprises | −0.18336 | −0.766 | 0.4479 | 1.222598 | |

| (0.23939) | |||||

| Emotions of the ego and the thou | |||||

| Accepting innovative behaviors | 0.29533* | 2.597 | 0.0128 | 1.208278 | |

| (0.1137) | |||||

| Posthumous fame is not important | 0.65905* | 2.655 | 0.0111 | 1.449015 | |

| (0.24821) | |||||

| Uninterested in wealth accumulation | −0.42665 (.) | −1.73 | 0.0908 | 1.32888 | |

| (0.24661) | |||||

| Social emotions, cultural, and political values | |||||

| Meritocracy | −0.27744* | −2.523 | 0.0154 | 1.130403 | |

| (0.10997) | |||||

| Cultural change | −0.23516 (.) | −1.924 | 0.061 | 1.396668 | |

| (0.12224) | |||||

| Altruism | −0.06149 | −0.517 | 0.6076 | 1.320921 | |

| (0.11888) | |||||

| Social adaptability | −0.09033 | −0.803 | 0.4266 | 1.183832 | |

| (0.11254) | |||||

| Seeking financial gain | 0.26903 | 0.989 | 0.3281 | 1.254692 | |

| (0.27196) | |||||

| Type 2 thinking | |||||

| Reliance on experts’ opinion | −0.13259 | −1.117 | 0.2704 | 1.318039 | |

| (0.11875) | |||||

| Emotion regulation | −0.14089 | −1.266 | 0.2124 | 1.157781 | |

| (0.1113) | |||||

| Demographics | |||||

| Level of education | 0.25849* | 2.201 | 0.0331 | 1.288708 | |

| (0.11742) | |||||

| R2 = 0.54 | R2adj = 0.4116 | ||||

| The Breusch-Pagan test for homoskedasticity indicated no heteroskedasticity in the model. The p-value is 0.3144, which is greater than 0.05. | |||||

| No. observations: 43 | |||||

Notes: Standard errors are reported in parentheses. The symbol (.) indicated significance at p < 0.1 level. * denotes significance at p < 0.05. VIF analysis indicated no significant multicollinearity between the variables since they took values below the threshold of 5. Thus, all variables provide unique information.

The constructed model explains approximately 41 % of innovative crisis management. The variables affecting nontraditional crisis management belonged to the ego and thou emotions, social emotions, political values, and demographics categories.

As predicted, accepting innovative behavior significantly and positively influences the dependent variable. Furthermore, as with strategic planning, managers who choose innovative solutions during crises are not motivated by personal interest. However, not being interested in wealth accumulation plays a small but negative role in innovative crisis management. This may be because the increase-wealth motive drives innovation (Hessels et al., 2006); moreover, most wealth originates from innovation (Ayres, 1988).

The level of education positively and significantly influences innovative crisis management. This finding aligns with Lin et al. (2011), who found that a CEO's educational background is positively associated with a firm's innovative activities.

Another significant variable that negatively affects innovative crisis management is the belief that everyone should be rewarded based on skill and performance. This relationship may be explained by the meritocracy paradox, which states that organizations emphasizing meritocratic values can unintentionally introduce biases and create unfavorable outcomes (Castilla & Benard, 2010). Similarly, the less significant and negative influences of accepting cultural change can be understood through this perspective.

Being a pragmatistThe regression analysis results using pragmatic thinking as the dependent variable are shown in Table 5.

Regression analysis for pragmatistic thinking.

| Variable | Estimate | t-value | p-value | VIF test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social emotions, cultural, and political values | ||||

| Tradition | 0.137 (.) | 1.775 | 0.077965 | 1.125048 |

| (0.0773) | ||||

| Type 2 thinking | ||||

| Reliance on experts’ opinion | 0.291*** | 3.861 | 0.000169 | 1.073759 |

| (0.0755) | ||||

| Effect of macro negative feelings | 0.195* | 2.604 | 0.010173 | 1.056927 |

| (0.0749) | ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 0.142* | 1.908 | 0.058298 | 1.038866 |

| (0.0743) | ||||

| R2 = 0.2253 | R2adj = 0.204 | |||

| The Breusch-Pagan test for homoskedasticity indicated no heteroskedasticity in the model. The p-value is 0.1757, which is greater than 0.05. | ||||

| No. observations: 146 | ||||

Notes: Standard errors are reported in parentheses. The symbol (.) indicated significance at p < 0.1 level. * denotes significance at p < 0.05. *** denotes significance at p < 0.001. VIF analysis indicated no significant multicollinearity between the variables since they took values below the threshold of 5. Thus, all variables provide unique information.

The constructed model explains approximately 20 % of pragmatic decision-making, indicating that structured thought depends on several factors beyond the present model. However, the emotional factors affecting the dependent variable merit further examination to provide insights into the relationship between emotions and self-assessed rationality. The variables affecting pragmatic decision-making belong to the social emotions and political values, Type 1 and 2 thinking, and demographics categories.

The most notable positive influence of pragmatic decision-making is exerted through seeking technical advice from experts in the field. Overall, managerial decision-making in business and industry relies on expert opinions, particularly concerning complex issues (Vanícek et al., 2011). It has also been shown that pragmatic decision-making is positively motivated by the need to mitigate the effects of large-scale, exogenous, negative events. Age is another key factor affecting this variable, which aligns with previous findings that link age to managerial decision-making performance (Taylor, 1975).

A lesser yet positive influence on pragmatic decision-making is the importance of tradition, both in terms of organizations and society. Tradition comprises well-established, respected beliefs and represents a slow, dynamic process (Shanklin, 1981). Anthropologically, it is a preventative force working against change and is often seen as an irrational emotional response (Shanklin, 1981). Thus, the positive impact of tradition on pragmatic decision-making can be understood as a Type 1 thinking process. Tradition involves stereotypical behavioral responses in familiar circumstances, facilitating decision-making processes. While the influence of tradition on pragmatism is contradictory, it can be seen as a “rational” choice since tradition is built upon established and tested norms.

Discussion and implicationsIn the past, efficient managerial decision-making depended exclusively on analytical thinking, monitoring, observation, and forecasting. This can be attributed to the reduced complexity and uncertainty of the global landscape. Today, emotional and judgmental processes are also required to predict successful outcomes. Some of the transformative forces impacting the complexity of managerial decision-making relate to high global connectivity, higher systematic risk, and information overload. In these situations, managers cannot choose between analytic and personal (intuitive) approaches to problems (Simon, 1987); effective managerial decision-making now requires a blend of both approaches more than ever.

This study bridges the dichotomy in managerial decision-making theories by revealing the interplay between emotional factors and the structured elements of managerial decision-making, such as strategic planning, innovative crisis management, and pragmatic decision-making. The involvement of emotions in managerial decision-making is crucial for fostering long-term vision and innovative behaviors. This finding challenges the neoclassical approach to managerial decision-making, which assumes that managers operate completely rationally without the involvement of emotions. The traditional normative approaches overlook the adaptive role of emotional processes (Markic, 2009), while dual-process theories are more suitable for analyzing decision-making dynamics (Markic, 2009). This study offers a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach to analyzing emotions in decision-making, presenting a systematic framework for thoroughly and effectively evaluating the relationship between emotions and managerial decision-making (Alvivo & Franco, 2017).

Understanding how emotions impact managerial decision-making is key to designing training and lifelong learning strategies. Emotional awareness and intelligence training can enhance leadership and improve decision-making processes (Aloitabi, 2022). It follows that lifelong learning courses can cultivate emotions as competencies (Boyatzis, 2021). However, given the varied nature of emotional experiences, personalized training is crucial to ensure quality lifelong learning.

Personalized training tailors learning experiences to meet each learner's needs, abilities, and interests, aiming to enhance the engagement, understanding, and retention of knowledge (Kay, 2008). In managerial training, this could involve manager behavioral evaluations, consideration of their interests, and the industry context. Using this data, experts can develop new strategies to build essential emotional and practical skills for effective decision-making, including managing people and new technologies.

Enhancing emotional understanding and its impact on decision-making can be crucial in the artificial intelligence era (Noponen, 2019). Provided that managers utilize both emotional and rational decision-making activities, there could be fruitful, ethical, and efficient use of artificial intelligence as an auxiliary means of decision-making. Emotions signal new insights and solutions that artificial intelligence cannot generate. Thus, integrating emotional factors expands managers’ decision-making beyond pure logic.

More specifically, gaining a deeper understanding of the behavioral and emotional factors affecting structured managerial decision-making reshapes the perception of its “irrational” influences. This study found that emotions influence analytical managerial decision-making, which can be directly or indirectly related to Type 2 thinking; Type 2 thinking is considered deliberate and rational. The presence of basic emotions through negative events in life positively motivated future readiness. This finding highlights the rational adaptation to disappointment and acceptance of organizational norms like turnover and individual responsibility, especially in response to large-scale negative events (Harrison & March 1984).

Managerial decision-making is driven less by managers’ personal interests like posthumous fame or wealth accumulation incentive and more by advancing the interests of the firm they work for, such as adopting innovative behaviors even at the cost of authority or prioritizing financial gain over social impact. These findings reflect the complex personalities of managers as outcome-oriented individuals who embrace different opinions and ideas (acceptance of polyphony) and understand that emotional situations might affect their performance. Awareness of how emotions affect managerial performance enables managers to adapt their mental patterns to accommodate the complex demands of managerial decision-making (Wallace & Rijamampianina, 2005).

Interestingly, overemphasizing meritocracy and embracing cultural change may undermine efficient managerial decision-making and induce biases. However, balancing respect for tradition with the ability to think innovatively and rationally is an essential quality of leadership (Wallace & Rijamampianina, 2005). The consulting role of tradition in decision-making is a Type 1 mental process that ensures continuity and consistency with past decisions. Additionally, expertise gained through age and education positively contributes to effective managerial decision-making.

Type 2-related emotional factors and the use of mental shortcuts through respect for tradition are closely tied to risk aversion, which was observed in 66 % of the sample when tested with two questions based on the Allais paradox (Allais, 1953). However, risk aversion is not an inherently irrational bias (Nagaya, 2021b), as individuals often aim to behave rationally; while risk preference influences reasoning, it is based on rational principles. The present study supports the view that emotional traits connected to managerial decision-making cannot be considered “irrational.” Moreover, human rationality can be described as an intentional action towards one or more goals chosen before the decision-making process (Rubin, 2011). These behaviors and choices are culture-specific and are redefined by social and socioeconomic conditions (Rubin, 2011). Thus, rationality should be examined within the boundary conditions determined by specific cultures and times (Rubin, 2011). Emotions represent a psychological meaning, extend into a culturally expressive function, and provide knowledge of a group's organization and operation (Lutz & White, 1986).

These findings extend the link between this style of managerial decision-making and the pathogenies of the Greek production structure. The main pathogenies of the Greek production structure relate to (i) over-regulation and slow implementation of institutional changes, (ii) high concentrations of small- and medium-sized firms, and (iii) failure to support innovation due to the relatively slow integration of technological development (Petrakis, 2022, 2024). These characteristics reflect risk aversion in decision-making, reinforcing the production structure's conservative tendencies and restraining managerial incentives toward pursuing transformative changes in the production structure. On the other hand, the emergence of risk-averse behaviors in decision-making is a prerequisite for conserving the stability of the weak Greek production structure to avoid jeopardizing its existence.

In the context of the Greek economy, the findings show that the management styles of small and medium-sized firms cannot sufficiently contribute to economic dynamism, which requires accountable risk-taking. If these concerns are not addressed, proactive and risk-taking managerial decision-making will not occur. This conjecture directly relates to policymaking quality, providing insights into the relationship between managerial decision-making and macroeconomic policies. Studying managerial behavior as an accumulative effect helps to explain how professional incentives evolve alongside culture and societal stereotypes. Understanding the complexities of successful managers’ personalities within a production structure facilitates the understanding of several economic issues and the evaluation of the real economy.

A limitation of this study is the influence of Greece's sociocultural context, as managers in Greece operate differently due to the nation's cultural and business norms. This suggests a need for future research to conduct a comparative behavioral analysis of efficient managerial decision-making between a nexus of geographical regions, such as the United States or the European North (i.e., Denmark and Finland).

ConclusionThis study explores how managerial decision-making operates beyond the strict rationality of neoclassical economic theory, focusing on the mechanics of animal spirits (spiritus animalis) as an emotional mindset (Akerlof & Shiller, 2010). These emotional factors shape managerial decision-making, offering a modern perspective for organizational theory beyond the existing theoretical paradigm. The study analyzes the nature of emotional factors influencing managerial decision-making in efficient small- and medium-sized firms in Greece, using three key variables: (i) strategic planning, (ii) innovative crisis management, and (iii) pragmatism.

The findings show that all layers of emotional culture influence managerial decision-making. Basic emotions, such as reactions to negative surprises, ego-driven emotions related to innovation, financial gain, posthumous fame, wealth, and social values concerning tradition, cultural change, and meritocracy, all play a significant role. Type 2 thinking—relying on experts, emotional awareness, accepting diverse perspectives, and adjusting strategies in response to large-scale negative events—also shapes decisions. Additionally, demographic factors, such as education level and age, further impact managerial decision-making.

Ultimately, the emotional factors involved in managers’ decision-making are directly or indirectly linked to Type 2 thinking. This suggests that, when understood as competencies rather than weaknesses or challenges, emotional factors can facilitate decision-making and are not necessarily irrational.

Adopting an interdisciplinary approach, drawing from various scientific disciplines, has both micro- and macroeconomic implications. On the microeconomic level, this stydy redefines managerial behavior, underscoring that by balancing emotion and reason, managers can cultivate a dynamic decision-making ethos that navigates present challenges and anticipates and adapts to future uncertainties. It also highlights the importance of including emotional intelligence and awareness in managerial training through personalized lifelong learning programs. On the macroeconomic level, it highlights the complex relationship between managerial behavior, cultural stereotypes, and policymaking efficiency, which can inspire managerial and entrepreneurial initiatives that drive economic dynamism. Finally, this study provides a behavioral framework for measuring accumulative behaviors through emotional culture.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAnna-Maria Kanzola: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Konstantina Papaioannou: Validation, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Panagiotis E. Petrakis: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.