This study addresses the fragmented understanding of the relationship between digital transformation (DT) and innovation by proposing a multi-level framework that integrates diverse disciplinary perspectives. This framework provides deep insight into how DT influences innovation. A systematic literature review was conducted, and based on the findings, a research agenda was outlined as a roadmap to guide future studies. This research contributes to the strategic change and innovation literature by providing a multi-level framework explaining how DT-driven structural change affects innovation, considering various contingencies such as market dynamics, technological advancements, and organizational capacities. Additionally, this study contributes to the innovation and strategic information systems domain by demonstrating that DT's role as a strategic asset for achieving innovation should align with firm capabilities, structural characteristics, and environmental and external dynamics.

Digital transformation (DT) has been defined as a “fundamental change process enabled by digital technologies that aim to bring radical improvement and innovation to an entity (organization, business network, industry, or society) to create value for its stakeholders by strategically leveraging its key resources and capabilities” (Gong & Ribiere, 2021, p. 10). Recently, DT initiatives have become a significant focus of companies’ investments (Appio et al., 2021; Calderon-Monge & Ribeiro-Soriano, 2023) and have made a substantial impact on the growth of national economies (Taylor, 2022). In 2018, digitally transformed companies contributed approximately 13.5 trillion U.S. dollars to the global GDP (Calderon-Monge & Ribeiro-Soriano, 2023). In 2022, the adoption of digital transformation in firms grew. In the same year, the number of organizations intending to implement data analysis or analytics programs increased significantly compared with the previous year, and 30% of the organizations planned DT investments (Taylor, 2022). Moving forward, DT speed continued to increase. Expenditures on DT are projected to reach 2.15 trillion U.S. dollars by 2023 (Sherif et al., 2024). By 2025, a new milestone will be achieved in DT's share of digitalization projects. Platform-driven interactions account for approximately two thirds of the 100 trillion U.S. dollars market. In the same year, approximately 90% of the new enterprise applications are predicted to integrate artificial intelligence (AI) into their processes and product offerings (Appio et al., 2021). Looking ahead to 2027, global spending on DT is expected to rise to 3.9 trillion U.S. dollars (Elsersy et al., 2021). This substantial investment highlights organizations’ increasing awareness of and reliance on DT to innovate and grow.

Different factors have affected this accelerated pace and increased commitment to DT initiatives. The most significant issues are environmental concerns (Minami et al., 2021; Wang & Su, 2021), efficiency and productivity issues (Müller et al., 2018,; 2019; Sivarajah et al., 2020), and COVID and global health problems (Reuschl et al., 2022; Wade & Shan, 2020; Li et al., 2022b). Whether pushed by external shocks or competitive pressures or by environmental or efficiency desires, such pervasive DT has significantly affected organizational routines, structures, processes, practices, and outcomes. These changes have considerably affected innovation and related processes, redefining how companies renew their business models to introduce product and process innovation (Bresciani et al., 2021).

Along with these disruptions to the industrial landscape, scholarly research has enhanced our understanding of the relationship between DT and innovation. Scattered across various domains and disciplines, literature provides significant insights into this interplay. However, this approach is fragmented and piecemeal. For instance, from a strategic viewpoint, realizing innovation outcomes stemming from DT is imperative, considering organizational, technological, and network capabilities (e.g., He et al., 2023; Yang & Du, 2023; Yao et al., 2023) and its role in driving competitive advantage for firms (e.g., Ferreira et al., 2019; Y. Li et al., 2022; Y. Zhang et al., 2023). Using a service or marketing lens, DT's role in customer engagement in innovation and its contribution to value co-creation have gained scholarly attention (e.g., Hunke et al., 2022; Kamalaldin et al., 2020; Rohn et al., 2021). Other studies relying on information systems approaches have focused on how emerging digital technologies (such as AI) affect companies’ innovation decisions and outcomes (e.g., Sun et al., 2024) or how the pervasive application of digital technology or its features can affect innovation networks (e.g., Tang et al., 2023; Xing et al., 2023) or improve value creation and capture in regional innovation ecosystems (Wang & He, 2024; Yang & Deng, 2023).

In addition to the fragmentation of DT–innovation research in different domains (Appio et al., 2021), existing research tends to adopt different levels of analysis (Nambisan et al., 2019) and varies in terms of its theoretical focus, conceptualization of DT (Vial, 2019), and evaluation of the boundary conditions affecting the benefit of DT for innovation. Most studies tend to accept DT's positive effect on performance as given (X. C. Guo et al., 2023), discounting the structural and institutional characteristics and contingencies that affect the scope and magnitude of this effect. Therefore, the implications of DT in innovation are yet to be established (Nambisan et al., 2017).

To bridge this gap, this study investigates the innovation value of DT through a systematic literature review (SLR). This method is well-suited to the fragmented nature of existing research (Tranfield et al., 2003). It synthesizes previous studies and strengthens the knowledge base, while ensuring transparency and reducing bias (Williams Jr et al., 2021).

Our study contributes to the strategy domain by offering a multi-level analytical framework illustrating how structural changes through DT influence a firm's innovation and performance. It further highlights innovation as a multifaceted, multi-level process that occurs as firms implement digital structural changes alongside other factors operating at the managerial, firm, industry, and broader levels. Additionally, it extends the discussion of information systems (IS) on digital affordances and their role in innovation (Nambisan et al., 2017, 2019) to strategy and innovation disciplines, examining DT as an innovation strategy that drives competitive advantage (e.g., Appio et al., 2021).

Research methodsDesignFollowing Denyer and Tranfield (2009), Denyer et al. (2008), and Tranfield et al. (2003), this study used an SLR approach to strengthen methodological rigor (Thorpe et al., 2005). SLRs have gained popularity in management and business literature owing to their high procedural analytical objectivity and transparency (Hallinger, 2013). Unlike traditional reviews, SLRs enhance rigor, validity, and generalizability (Denyer & Tranfield, 2009). They synthesized prior research to reinforce the knowledge base of a specific subject while maintaining the principles of openness and minimizing bias (Williams Jr et al., 2021).

Moreover, reliable knowledge of the research topic can be gained through well-defined systematic practices and transparently reproducible procedures (Tranfield et al., 2003). Therefore, we conducted an SLR to synthesize fragmented research on the effects of DT on innovation across different disciplines. We adopted the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework (Moher et al., 2016) to ensure transparency and reproducibility, with each step clearly defined.

ProcedureFollowing Atif et al. (2021), Tranfield et al. (2003), and Bilbao-Ubillos et al. (2024), a literature review was conducted in three phases: planning and implementation, analysis and synthesis, and reporting.

Phase 1

Planning and implementation

A planning protocol was designed to guide the overall study. It formulated research questions, established review boundaries, selected keywords and search terms, selected search databases, and defined the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Owing to its extensive coverage of peer-reviewed journals in management and business, the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) was selected as the primary database. A scoping review was performed to identify the keywords. To ensure the inclusiveness and comprehensiveness of the review, the keywords were refined through consultations with two domain experts.

Phase 2

Analysis and synthesis

Two analyses were performed on the selected articles, including a bibliographic analysis and a content analysis. The bibliographic analysis was used to identify key publications, trends, and methodological and theoretical approaches. Two independent reviewers conducted data extraction to ensure reliability. Discrepancies were resolved by thoroughly discussing the relevance of articles for inclusion. The content analysis was focused on identifying the main themes in the literature and categorizing them into distinct categories.

Phase 3

Reporting

At this stage, the findings were synthesized to map the role of DT in innovation. A multi-level framework was developed to explain the current literature on the DT–innovation interplay.

Review questionSLRs offer reliable answers to well-defined and specific research questions (Yuan & Hunt, 2009). They provide a clear, unbiased, and comprehensive summary of the current understanding of a specific research question (Tsafnat et al., 2014). SLRs “bear on a particular question, using organized, transparent, and replicable procedures at each step in the process.” (Littell et al., 2008, pp. 1–2). Therefore, a successful SLR requires clear review questions (Kraus et al., 2021; Lame, 2019; Rother, 2007). The primary research question was, “What role does DT play in innovation in firms?” Following previous studies (Bilbao-Ubillos et al., 2024; Calderon-Monge & Ribeiro-Soriano, 2023; Paschou et al., 2020), two sub-research questions were proposed.

-RQ1

What does the current literature reveal about the impact of DT on innovation?

-RQ2

Based on the findings of our study, what are the recommended directions for future research?

Review boundariesFollowing recent SLR studies (Bilbao-Ubillos et al., 2024), five criteria were used to exclude/include and refine the articles: (1) publication type, (2) conceptual boundaries, (3) search boundaries, (4) specified timeframes, and (5) keywords.

Step 1: The conceptual boundaries of DT were defined. Definitions of DT vary in focus, ranging from technology-driven changes to more holistic views encompassing organizational and strategic transformations. The lack of a parsimonious and universally accepted definition (Vial, 2021) highlights the complexity of DT and the challenges in conceptualizing it as a multifaceted phenomenon. While some scholars emphasize the technological dimension, others focus on DT's broader organizational, strategic, and societal impacts. The following section provides a critical review of existing conceptualizations to synthesize a definition of DT that is the best fit for investigating its interplay with innovation.

The DT literature shows that, although the term has been increasingly discussed and adopted, it has some conceptual clarity issues (Vial, 2021). Moreover, its scope varies significantly across different contexts. Scholars have offered some basic and foundational definitions of DT. (Vial, 2021) defined DT as the improvement of an entity by triggering significant changes through information, computing, communication, and connectivity technologies. This definition establishes the integrative role of digital technology in reshaping business strategies and operations. Gong and Ribiere (2021) conceptualized DT as “a fundamental change process enabled by digital technologies that aim to bring radical improvement and innovation to an entity, such as an organization, business network, industry, or society, to create value for its stakeholders by strategically leveraging its key resources and capabilities” (p.12).

By contrast, Li et al. (2018) focused on DT as a transformation driven by information technology that changes business processes, operational routines, and organizational capabilities. This perspective emphasizes DT's disruptive potential for business models. Similarly, Chanias et al. (2019) emphasized DT's extra-organizational influence by describing it as a holistic transformation associated with technological and economic changes at the organizational and industry levels.

Warner and Wäger (2019) tended to rely on technological dimensions. They defined DT as the use of digital technologies (social media, mobile devices, analytics, and embedded devices) to enable significant business improvements. Nambisan et al. (2019) added to this by framing DT in terms of its transformational or disruptive implications. According to these authors, DT leads to new business models, products, and customer experiences.

However, some definitions, such as those proposed by Schallmo et al. (2017) and Nadkarni and Prügl (2021), focus primarily on organizational changes triggered by digital technologies. Schallmo et al. (2017) described DT as involving the networking of actors (e.g., businesses and customers) and applying new technologies to enhance company performance. Nadkarni and Prügl (2021) viewed DT as an organizational change shaped by the widespread diffusion of digital technologies. Both definitions emphasize structural changes within organizations that are driven by digital adoption. Hanelt et al. (2021, p. 1160) built on this by defining DT “as organizational change that is triggered and shaped by the widespread diffusion of digital technologies.”

Some definitions approached DT more comprehensively. They conceptualized it as transforming business activities, processes, competencies, and models to leverage digital technologies. This approach aligns with the perspective of Bughin and Van Zeebroeck (2017), who highlighted that DT is not just about technological integration. Instead, it redefines competitive advantages and value creation.

A recurring theme across these definitions was the distinction between digitization, digitalization, and DT. Digitization refers to converting information from analog to digital, whereas digitalization involves transforming digital data into value-creation processes. DT is more substantial. It encompasses a complete rethinking of how organizations create and deliver value. This distinction is critical. Some definitions, such as those of Warner and Wäger (2019) and Fitzgerald et al. (2014), may conflate digitalization and DT.

While many researchers have concentrated on DT's technological aspects, others, such as Berghaus and Back (2016), focused on its corporate dimensions. They argued that DT is a continuous process that requires not only the adoption of new technologies but also organizational changes in structure, processes, and governance. This view was further emphasized by Sacolick (2017), who highlighted that DT involves agile organizational developmental processes.

The above review shows that, while DT is widely discussed, its conceptual clarity and scope vary significantly across contexts. Synthesizing the previous definitions, we define digital transformation as “an ongoing socio-structural change that leverages digital technologies to create new value toward sustained competitive advantage.” This synthesis has different components that align with the key aspects of DT reported in the literature. Its “ongoing” component refers to the “continuous integration and evolution of digital technologies” (Gupta, 2018; Morakanyane et al., 2017; Warner & Wäger, 2019). The “socio-structural change” component is rooted in restructuring business models, processes, and organizational structures (Hanelt et al., 2021; Hess et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018). It also emphasizes that DT is not merely a technological or strategic phenomenon, but also a social phenomenon across the organization dealing with human and human–technology relationships. The phrase “structural” emphasizes that DT is not merely associated with changes in roles or tasks conceptualized by digitalization and digitization. Rather, it includes changes in organizational structures, distinguishing it from digitalization and digitization. The other component, that is, “leverages digital technologies,” highlights the central role of the technology described by Nambisan et al. (2017) and Schallmo et al. (2017). The elements “create new value” and “sustained competitive advantage” are core ideas in Gupta's (2018) perspective. In their view, DT is a new value proposition that considers organizational strategy. The component “sustained” refers to the emphasis on sustained competitive advantage conceptualized by Morakanyane et al. (2017) and Fitzgerald et al. (2014).

This definition further helps to conceptualize its relationship with Schumpeter's (1934) definition of innovation as a new production function, including new products, methods, markets, and organizational structures. Schumpeter's focus on renewing the organizational structure and exploring untapped markets resonates with the restructuring and market expansion components of DT, as discussed by Li et al. (2018) and Hanelt et al. (2021). By defining innovation as creating new production functions, Schumpeter's view supports the idea that DT is not merely about digitizing existing processes but fundamentally reshaping business models, competition, and value creation. This holistic and inclusive approach is obvious in our definition of DT as an ongoing socio-structural change that leverages digital technologies to create new value toward sustained competitive advantage. This definition reflects Schumpeter's conceptualization of innovation as the introduction of new production and competition methods. Moreover, Schumpeter's new products, methods, and organizational renewal as innovations reflect the idea that DT drives long-term innovation. As Warner and Wäger (2019) and Vial (2021) highlight, integrating digital technologies into organizational processes creates new product and service opportunities by improving production methods and accessing new markets. These ideas are central to Schumpeter's definition of innovation. Finally, the structural change component in our definition further allows us to understand the structural and technological changes brought about by DT as the creation of new production functions. This synergy justifies the use of our definition of DT as a framework for investigating its impact on innovation. This is particularly relevant when studying how DT boosts organizational renewal, technological advancement, and market expansion (Schumpeter's innovation types).

Step 2

The search boundaries were delimited to encompass journals indexed in the SSCI because of the comprehensive indexing of high-quality, peer-reviewed journals in management, business, and social sciences (Calderon-Monge & Ribeiro-Soriano, 2023). Moreover, for quality assurance, and following previous reviews (Baral et al., 2023; Pawar, 2023; Sharma et al., 2023), only articles that appeared in the Australian Business Deans Council (ABDC) list, based on the 2022 edition of the journal ranking guide of the ABDC were included.

Regarding publication type, the review focused on journal articles. The language was set to be English. Book chapters, industry articles, editorials, conference proceedings, and book reviews were excluded (Calderon-Monge & Ribeiro-Soriano, 2023; Paschou et al., 2020). Articles discussing the interplay between DT and innovation were also included. Studies focusing solely on either concept, without linking them, were excluded. Moreover, to ensure a focus on high-quality and rigorous academic research, we excluded papers that were not peer reviewed. No timeframe was specified to ensure maximum inclusion of the publications.

Step 3

Keyword selection was performed as a critical task (Kraus et al., 2021). We scoped the literature and brainstormed with academics to map relevant keywords (Arksey & O'malley, 2005). After identifying the relevant keywords (Table 1), a combination of keywords was used to identify articles on “Digital Transformation” and “Innovation.” The search strings/formulas were defined based on AND/OR operators. For example, “digita* transfor*” was used to capture variations such as “digital transformation” and “digitalized transformation.”

Keywords and search strategies used to identify sample articles.

| Keyword | Search String |

|---|---|

| DT | "Digita* transfor*" |

| Innovation | Innovation" OR "Innovation Performance" OR "New Market" OR "Research And Development" OR "Novelty" OR "Innovative" OR "Product Innovation" OR "New Service" OR "Enhancement" OR "Radical" OR "Management Innovation" OR "Innovation Efficiency" OR "Technological Innovation" OR "Product Improvement" OR "Diffusion" OR "Research & Development" OR "Process" OR "Exploratory Innovation" OR "Improvement" OR "Process Innovation" OR "Structural change" OR "competitive advantage" OR "Technical Knowledge" OR "Incremental Innovation" OR "Exploitative Innovation" OR "Innovat*" |

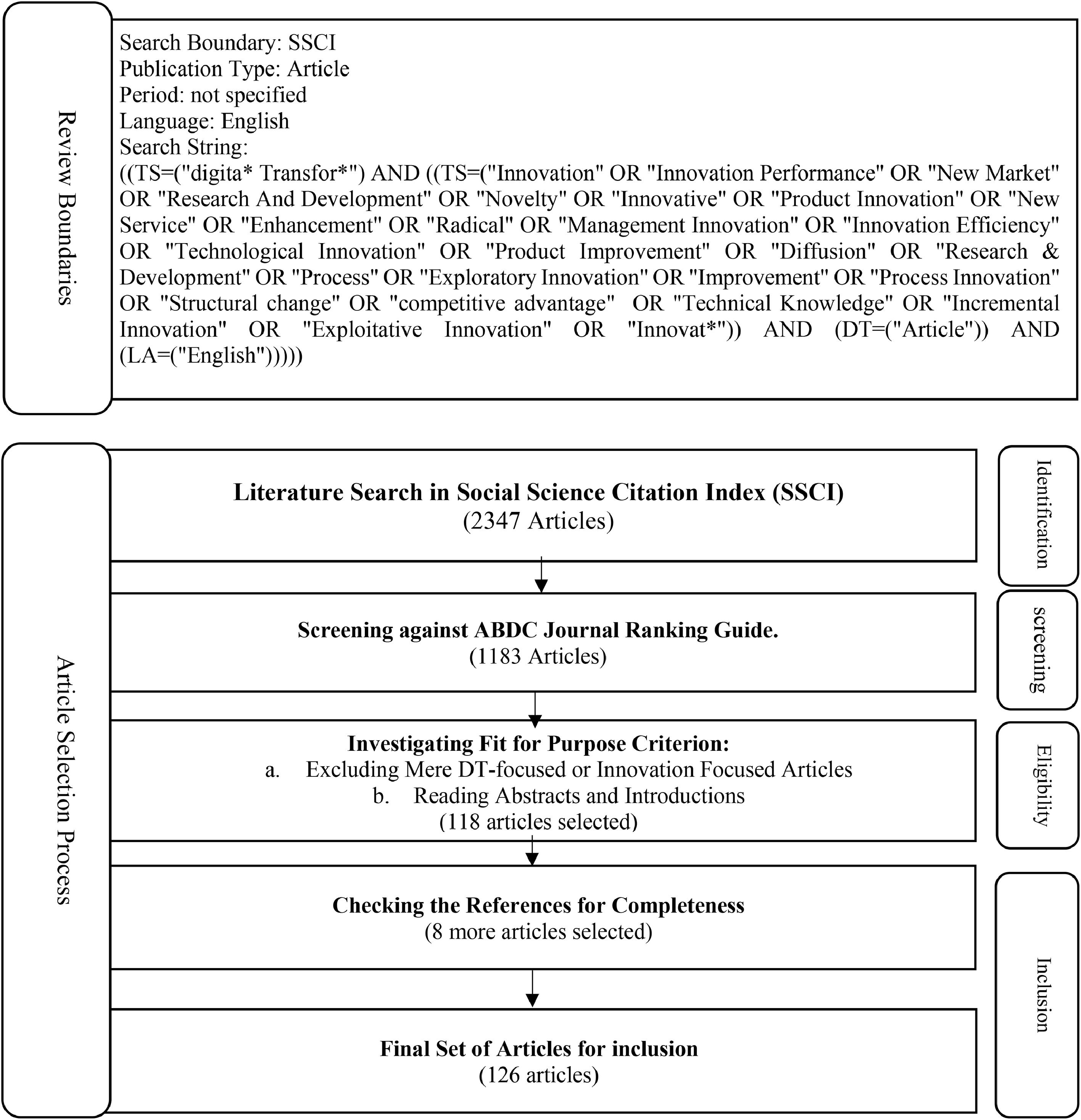

A PRISMA approach (Moher et al., 2016) was used to identify, screen, check eligibility, and select relevant studies based on our exclusion/inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1).

- -

Identification: The identification stage involved setting review boundaries to identify relevant contributions that would be considered for further screening. A literature search was conducted using SSCI, based on the keywords listed in Table 1. First, following Kraus et al. (2022), we used the search string “Digita* transfor*” to identify the papers written on DT and distinguish them from the contributions about associated terms and concepts. We searched for document topics (titles, abstracts, and keywords). This approach identified relevant papers published on this topic. We then refined the results using innovation keywords (Table 1) to identify the contributions of DT to innovation (2675 relevant contributions). Next, we restricted the search to peer-reviewed articles. This reduced the number of contributions to 2398 articles. Finally, the paper was written in English. This step further reduced the number of articles to 2347.

- -

Screening: To maintain the quality of the reviews, the articles were screened against the ABDC journal guide rankings. Only articles published in ABDC-listed journals were included in this study. Following this process, the number of articles was further reduced to 1183.

- -

Eligibility: Next, the eligibility for article inclusion was assessed using the fit-for-purpose criterion (Felicetti et al., 2023; Kumar et al., 2022). Two actions were performed at this stage. First, since the focus was to investigate the DT-innovation interplay, the articles exclusively focused on innovation and DT was excluded. Second, we read the abstracts and introductions of the papers to select the final articles. The two authors extracted each article's theoretical perspectives, methodology, findings, and implications for innovation. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved through a consensus to minimize bias, which led to the inclusion of 118 articles in the study.

- -

Inclusion: The database search was followed by a cross-reference analysis to address the potential limitations of keyword searches and ensure completeness (Paschou et al., 2020). Eight additional articles were retrieved and screened based on the exclusion/inclusion criteria. Following this step, 126 articles were chosen to be included in our study. We analyzed and evaluated this set of articles to identify the bibliographic structure and mechanisms through which DT affects innovation. This analysis yielded a multi-level framework that mapped the research on DT-driven innovations and will guide future research.

- -

Following previous studies (Bruton & Lau, 2008; Xu & Meyer, 2013), and to provide a comprehensive view of how DT brings innovation to firms, two complementary analyses were performed on the selected articles: bibliographic and qualitative content analysis. Such an approach enables a researcher to perform analysis and synthesis, that is, to explore the structure and content of existing research. In the analysis part, the researcher examines the structure of the existing research by providing descriptive and statistical analysis of the sample articles. In the context of the current research, the bibliographic analysis identified statistical and descriptive research patterns on the DT–innovation interplay along the spatial and temporal dimensions, while the qualitative content analysis yielded a comprehensive framework that mapped the research domains of DT-based innovations and identified how DT may influence innovation.

For the bibliometric analysis, the authors extracted data from the articles, including publication outlets, publication years, overall time trends, theoretical perspectives, methodologies, and key findings. Similar bibliometric data have been reported in high-impact SLRs (Calderon-Monge & Ribeiro-Soriano, 2023; Chintalapati & Pandey, 2022).

The qualitative content analysis aimed to identify general patterns in the existing literature. Following Kafetzopoulos (2022) and Shahbaz and Parker (2022), we synthesized our findings using an AMO framework by analyzing antecedents (A), mediators/moderators (M), and outcomes (O). The findings are summarized in the following sections.

Part A: Bibliometric resultsThe distribution of the sample by publication outlet and disciplineTable 2 presents the distribution of the articles per publication outlet. Overall, technology and innovation management dominated the sample. The next tier was business and management, finance, and knowledge management. This distribution across disciplines suggested that the impact of DT on innovation was multifold and interdisciplinary. The most frequent outlets included Technological Forecasting and Social Change (10.32%), Technology Analysis & Strategic Management (8.73%), and The Journal of Business Research (8.73%).

The distribution of the sample by publication outlet and discipline.

| Publication Outlet | Record Count | % of 126 | Discipline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technological Forecasting and Social Change | 13 | 10.32% | Technology and Innovation Management |

| Technology Analysis & Strategic Management | 11 | 8.73% | Technology and Innovation Management |

| Journal of Business Research | 11 | 8.73% | Business and Management |

| Journal of the Knowledge Economy | 8 | 6.35% | Knowledge Management |

| Finance Research Letters | 8 | 6.35% | Finance |

| Managerial and Decision Economics | 8 | 6.35% | Economics |

| European Journal of Innovation Management | 7 | 5.56% | Technology and Innovation Management |

| Journal of Innovation & Knowledge | 6 | 4.76% | Technology and Innovation Management |

| IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management | 6 | 4.76% | Engineering Management |

| Technology in Society | 6 | 4.76% | Technology and Society |

| Technovation | 3 | 2.38% | Technology and Innovation Management |

| Business Strategy and the Environment | 3 | 2.38% | Business and Management |

| Journal of Knowledge Management | 3 | 2.38% | Knowledge Management |

| Business Process Management Journal | 3 | 2.38% | Business and Management |

| Environment Development and Sustainability | 2 | 1.59% | Environmental Sustainability |

| Management Decision | 2 | 1.59% | Business and Management |

| Review of Managerial Science | 2 | 1.59% | Business and Management |

| Journal of Environmental Planning and Management | 2 | 1.59% | Environmental Planning and Management |

| Energy Economics | 2 | 1.59% | Economics |

| Journal of Information & Knowledge Management | 1 | 0.79% | Knowledge Management |

| Journal of Management & Organization | 1 | 0.79% | Business and Management |

| International Review of Economics & Finance | 1 | 0.79% | Finance |

| Journal of Environmental Management | 1 | 0.79% | Environmental Management |

| Business Horizons | 1 | 0.79% | Business and Management |

| Frontiers in Environmental Science | 1 | 0.79% | Environmental Science |

| International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management | 1 | 0.79% | Technology and Innovation Management |

| European Journal of Finance | 1 | 0.79% | Finance |

| Asian Journal of Technology Innovation | 1 | 0.79% | Technology and Innovation Management |

| Applied Economics Letters | 1 | 0.79% | Economics |

| Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management | 1 | 0.79% | Environmental Management |

| International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal | 1 | 0.79% | Entrepreneurship |

| Journal of Enterprise Information Management | 1 | 0.79% | Information Management and Systems |

| Journal of Global Information Management | 1 | 0.79% | Information Management and Systems |

| Long Range Planning | 1 | 0.79% | Business and Management |

| International Review of Financial Analysis | 1 | 0.79% | Finance |

| Academy of Management Discoveries | 1 | 0.79% | Business and Management |

| Journal of Product Innovation Management | 1 | 0.79% | Technology and Innovation Management |

| R & D Management | 1 | 0.79% | Research and Development Management |

| Information and Organization | 1 | 0.79% | Information Management and Systems |

Papers published in Managerial and Decision Economics and Finance Research Letters had the highest frequency (6.35% each) and reflected DT's economic and financial implications (or investment decisions regarding innovation outcomes). The second most frequent category was innovation journals; the European Journal of Innovation Management (5.56%) and the Journal of Innovation & Knowledge (4.76%) were well represented, with a particular interest in how DT influenced innovation processes and knowledge development within firms. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management (4.76%) and Technology in Society (4.76%) were the third-most represented categories, with a particular focus on the sociotechnical aspects of the DT-innovation interplay. Other journals have investigated DT's impact on sustainability and green initiatives, in addition to regular innovations. These journals included Business Strategy and the Environment (2.38%) and the Journal of Environmental Planning and Management (1.59%).

Journal of innovation & knowledge's (JIK) contribution to the DT–innovation nexusThe JIK has significantly contributed to conversations on DT and its innovation implications. JIK plays an evolving leadership role, and its contributions are summarized and discussed below.

JIK covered a wide range of topics, including the impact of DT on innovation performance (L. Li et al., 2022), digital leadership (Chatterjee et al., 2023), and public policy (Peng & Tao, 2022). These include a strategic perspective on risk-taking (M. Y. Liu et al., 2023), an assessment of total factor productivity (Yu et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2023b), and an evaluation of the role of social capital in innovation (Lyu et al., 2022). Additionally, sector-specific insights into asset-intensive organizations (Buck et al., 2023), higher education (R. J. Li et al., 2024), and agribusiness (Xue et al., 2024) were provided, along with environmental innovation (Hung & Nham, 2023) in small and medium (Bashir et al., 2023) and private enterprises (Chen & Yu, 2024).

For example, Yu et al. (2024) assessed the impact of DT on innovation investment in Chinese manufacturing firms. The authors reported a significant positive relationship between DT and investment in innovation. In their research, Total Factor Productivity (TFP) due to DT led to internal resource competition between the production and innovation departments. This study also provided policy recommendations for enhancing innovation investments in manufacturing firms. These firms are traditionally known as less innovative sectors. Xue et al. (2024) focused on Chinese agribusinesses. Their findings emphasized DT's role in facilitating access to essential resources in traditional sectors, such as technology, talent, and capital. Finally, Chen et al. (2024) investigated private enterprises and found that DT significantly promoted innovation, particularly in wealthy regions and larger firms (Zhang et al., 2023b).

The sample's distribution by yearFig. 2 summarizes the publications and citations on the DT–innovation interplay over the years. An increasing trend can be observed in publications and the running sum of citations. We computed a trend model for the number of publications and their citations over time. The model was significant at p ≤ 0.05 and shows that the citations per published document increased over the years. The number of citations has grown exponentially over the years. This increase foreshadows interest in this topic in the coming years.

Although a timeframe was not specified for the inclusion criteria, the sample papers that met the selection criteria were published between 2018 and 2024. This may be due to the global rise in DT and digital technology spending by firms in 2018–2023, which led to significant investments in DT and innovation activities (Taylor, 2022). In line with these trends in the industry, the academic landscape has experienced exponential growth in publications on the relationship between DT and innovation post 2017 (Appio et al., 2021) and a sharp increase in research evidence on DT published from 2018 onward (Calderon-Monge & Ribeiro-Soriano, 2023).

Distribution of methodological approachesTable 3 summarizes the research methodologies used across our sampled articles. The reviewed studies were categorized into quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, and conceptual papers. Quantitative methods dominated the samples, accounting for 73% of the studies. The most common techniques included panel regression models, PLS-SEM, Heckman two-stage models, and GMM. Qualitative methods represented 14.3% of the studies. Multiple case studies, grounded theory, and single case studies explored how DT affected performance outcomes, specifically innovation. Of the papers, 8.7% used mixed qualitative approaches with quantitative techniques, such as PLS-SEM and fsQCA. Conceptual studies, accounting for 4% of the total, explained the resource-based view (RBV) and dynamic capability view (DCV) views in the context of DT-enabled innovation.

Distribution of articles by methodological approaches.

| Category | Number of Papers | Percentage | Example Methodologies Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | 92 | 73.0% | Panel regression, Fixed-effect, and random-effect models, PLS-SEM, Fixed-effects Poisson model, Heckman two-stage model, Hierarchical regression, Serial mediation, Spatial Durbin model |

| Qualitative | 18 | 14.3% | Multiple case studies, Grounded theory, Single case study |

| Mixed Methods | 11 | 8.7% | Mixing qualitative methods with Questionnaire survey, PLS-SEM, and fsQCA |

| Conceptual | 5 | 4.0% | Conceptual frameworks based on theories such as resource-based view, diffusion of innovation theory, dynamic capabilities view, organization learning theory |

Table 4 summarizes the significant geographical concentration of studies and presents an overview of the geographical distribution of authors and funding sources for research papers on the effect of DT on innovation. Most papers (61.11%) were affiliated with Chinese institutions.

Distribution of articles based on country and funding status.

| Country | Number of Authors | Percentage (%) | Funding Source | Number of Papers | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 77 | 61.11% | Chinese-Funded | 70 | 55.56% |

| Taiwan | 9 | 7.14% | Non-Chinese-Funded | 28 | 22.22% |

| South Korea | 2 | 1.59% | Total Funded Papers | 98 | 77.78% |

| Norway | 1 | 0.79% | Unfunded Papers | 28 | 22.22% |

| Spain | 4 | 3.17% | Total Papers | 126 | 100% |

| Italy | 5 | 3.97% | |||

| Brazil | 2 | 1.59% | |||

| Saudi Arabia | 3 | 2.38% | |||

| United Kingdom | 4 | 3.17% | |||

| Germany | 2 | 1.59% | |||

| Portugal | 3 | 2.38% | |||

| United States | 6 | 4.76% | |||

| South Africa | 1 | 0.79% | |||

| India | 2 | 1.59% | |||

| France | 1 | 0.79% | |||

| Finland | 1 | 0.79% | |||

| Total | 126 | 100% | |||

This dominance can be attributed to China's substantial investment in digital technologies and its strategic focus on becoming a global leader in technological advancement. China's commitment was further evidenced in our sample, as 55.56% of the funded papers received support from Chinese institutions (in contrast to 22.22% of non-Chinese-funded papers). The articles’ focus and share of government-funded papers showed that China specifically targeted innovation through DT to renew its traditional industries and manufacturing sectors. Taiwan, the United States, the United Kingdom, Italy, and other European countries contributed significantly (14.7%, 4.76%, 3.17%, and 3.97% of the papers, respectively).

Distribution of articles by theoretical approachThe distribution of papers based on theoretical approaches is shown in Table 5. The DCV was the most prevalent at 8.7%, closely followed by the RBV at 7.1%, and the knowledge-based view (KBV) at 6.3%. Together, these studies highlight that many have considered the resource and knowledge integration dynamics to drive DT-enabled innovation. In addition, 5.6% of the studies used open innovation theory, which complemented the RBV, KBV, and DCV by focusing on external resources and knowledge.

The distribution of articles based on their theoretical approaches.

| Theoretical Approach | Record Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Capabilities View | 11 | 8.7% |

| Resource-Based View (RBV) | 9 | 7.1% |

| Knowledge-Based View (KBV) | 8 | 6.3% |

| Open Innovation Theory | 7 | 5.6% |

| Absorptive Capacity Theory | 6 | 4.8% |

| Technology-Organization-Environment (TOE) Framework | 6 | 4.8% |

| Innovation Ambidexterity | 5 | 4.0% |

| Environmental Management/Circular Economy | 4 | 3.2% |

| Institutional Theory | 4 | 3.2% |

| Organizational Learning Theory | 4 | 3.2% |

| Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) | 3 | 2.4% |

| Human Capital Theory | 3 | 2.4% |

| Organizational Change Theory | 3 | 2.4% |

| Search and Recombination Theory | 2 | 1.6% |

| Organizational Inertia Theory | 2 | 1.6% |

| Total Factor Productivity (TFP) | 2 | 1.6% |

| Organizational Unlearning Theory | 2 | 1.6% |

| Innovation Diffusion Theory | 2 | 1.6% |

| Path Dependency Theory | 1 | 0.8% |

| Low-Carbon Knowledge Search (LCKS) | 1 | 0.8% |

| Green Knowledge Management (GKM) | 1 | 0.8% |

| Herd Behavior Theory | 1 | 0.8% |

| R&D Strategy and Flexibility | 1 | 0.8% |

| Competitive Strategy Theory | 1 | 0.8% |

| Unspecified Theory | 26 | 20.6% |

| Total | 126 | 100% |

These knowledge mechanisms were further highlighted, considering that the absorptive capacity (AC) theory and technology-organization-environment (TOE) framework appeared in 4.8% of papers. Innovation ambidexterity, represented in 4% of the papers by focusing on internal and external knowledge, complemented the knowledge and resource mechanisms associated with the DT–innovation relationship and complemented the previous KBV, RBV, DCV, AC, and TOE perspectives.

Environmental management/circular economy, institutional theory, and organizational learning theory contributed equally (3.2%). Interestingly, 20.6% of the studies did not specify a theoretical framework. This highlights the need for greater theoretical rigor in future studies.

Part B: Content analysis resultsThis section synthesizes the findings of the content analysis on the relationship between DT and innovation. Following Khosravi et al. (2019), we employed a systematic content analysis method to translate textual content into distinct categories. Content analysis was conducted in five stages: open coding, coding sheets, grouping, categorization, and abstraction (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). An open code was assigned to each article during this process. These codes were then organized into broader categories such as grouping dynamic and technological capabilities under strategic capability moderators. The categories of moderators, environmental factors, and firm characteristics were integrated into a general “moderators” category. To ensure accuracy, the authors conducted each coding and grouping stage independently. We applied the AMO framework to classify the variables into antecedents, mediators, moderators, and outcomes (Shahbaz & Parker, 2022). The antecedent in our framework was DT, which influences firm innovation. Mediators represented the mechanisms that channel DT's effects on innovation, whereas moderators were boundary conditions that either strengthened or weakened the relationships between DT, mediators, and innovation outcomes. Finally, we synthesized the results into a multi-level framework visually representing the linkages between these categories (Fig. 3). The following sections discuss our findings regarding these linkages.

OutcomesThe results indicated that DT positively affected a firm's innovativeness (Chen & Yu, 2024; M. Y. Liu et al., 2023; Romero & Mammadov, 2024; Yu et al., 2024) and overall performance (X. C. Orero-Blat et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2023; Wang, 2023; Zhai & Liu, 2023; Guo et al., 2023b). DT could drive business models, products, and process innovations (Bresciani et al., 2021) and boost enterprise vitality by enhancing productivity by reducing asymmetric information and optimizing resource allocation (Yang & Deng, 2023; Yu et al., 2024).

Sample articles suggested that DT's effects on innovation could be shaped within and across an organization's borders. Internally, DT influenced labor inputs and promoted intrapreneurship (Cheng et al., 2023). It strengthens organizational innovation by establishing team cohesion, trust, and information exchange. These were the enablers of structural, strategic, and systemic innovation within the firm (Zhang & Fan, 2024). Moreover, DT could restructure management control systems (Pizzi et al., 2021; Wang & He, 2024) to make innovation practices more efficient.

Externally, DT improved a firm's capacity to absorb and transform knowledge and resources and enhance customer value creation through dynamic capabilities in small and medium enterprises. This supported the creation of new distribution channels, business models, and mechanisms of value delivery (Matarazzo et al., 2021). DT also facilitated knowledge recombination processes (layering, grafting, or integration) toward innovation (Lanzolla et al., 2021). Moreover, DT promoted open innovation by boosting collaboration and knowledge sharing within and beyond the firm (Kim & Park, 2024; Luan et al., 2024; Urbinati et al., 2020). These collaborations improved innovation quality and encouraged the disclosure of valuable information (Bereczki & Füller, 2024; Che et al., 2023; Pang & Wang, 2023). Furthermore, DT saved firm resources to support investment in patent applications and invention activities (Y. Zhang et al., 2023). DT also extended its influence across supply chains by improving network layouts. In doing so, DT facilitated knowledge sharing, enhanced resource integration, and enhanced customer innovation capabilities (Q. H. Liu et al., 2024). In addition, DT reduced innovation risk by alleviating financing constraints and reducing production costs (Q. H. Liu et al., 2024).

Regarding the types of innovation, DT drove both commercial and green/sustainable innovations (R. J. Lian & Zhang, 2024; Li et al., 2024; Ribeiro-Navarrete et al., 2023). For instance, for commercial innovations, cognitive computing capabilities enhanced firms’ entrepreneurial qualities such as risk-taking and proactiveness (Gupta et al., 2023; Korherr et al., 2023). Similarly, adopting AR/VR solutions in DT enabled various innovations, including product/service offerings, business processes, and business model innovations (Pessot et al., 2023). Additionally, smart technologies fostered digital process innovations by facilitating organizational unlearning and reconfiguring established processes (Wang et al., 2023).

DT also affected green and sustainable innovation (Zhao and Fang, 2023). It positively influenced green technology innovation (Du et al., 2023) by optimizing human capital, easing financial constraints, and increasing media attention (Lin & Xie, 2023; Lu et al., 2023; Qiong Xu et al., 2023). Moreover, DT enhanced the quality and quantity of green technological innovation by increasing R&D intensity and reducing risk (Y. Xu et al., 2023). Through this process, firms could strengthen their collaborative networks of innovation and access to financing (Tang et al., 2023).

DT's impact on innovation could be channeled through innovation ambidexterity, that is, simultaneous radical and incremental innovations (R. J. Li et al., 2024; Wang & He, 2024; Zhu & Li, 2023; Li et al., 2024b). DT affected a firm's breadth and depth of knowledge. This helped deepen the exploration and exploitation of new opportunities (Zhou, Yang et al., 2023). It was specifically associated with innovation radicality for firms with a high technological orientation in their top management teams (Pessot et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2023). Social media platforms utilized DT-enhanced ambidexterity through knowledge transfer practices (Scuotto et al., 2020). DT shaped radical and incremental innovations differently. The shape was an inverted U for incremental innovation and it had a direct linear effect (Duan et al., 2023).

Finally, although many of the above studies showed a positive link between DT and innovation, in line with Usai et al. (2021), we argue that firms did not always experience improved innovation performance. Therefore, we need to understand the mechanisms and boundary conditions highlighted below.

Mediators: Antecedents–outcomes linkThe effect of DT on outcomes was channeled through various mechanisms. Following a detailed review of the sample articles, we categorized these mechanisms differently from previous studies. Yang and Deng (2023) mentioned mechanisms such as alleviating information asymmetry, improving productivity, and resource allocation. Thus, we identified a more comprehensive list. These mechanisms inherently overlapped owing to the multiple affordances of digital technology. The identified mechanisms were categorized as resource optimization, financial and risk management, collaboration and knowledge amplification, and productivity and cost-efficiency. In the following sections, we discuss these mechanisms separately.

Resource optimization mechanismThe sample articles suggested that DT accelerated innovation by employing various strategies to enhance innovation output. It enabled firms to adapt quickly to evolving market demands by fostering cross-border collaborations, aligning closely with user requirements, and promoting co-creation experiences (Peng & Tao, 2022).

The reviewed articles also suggested that DT could optimize operational efficiency, labor utilization, and resource allocation. This optimization released organizational resources for further innovation (Lin & Xie, 2023; Matarazzo et al., 2021; Yang & Deng, 2023). DT strengthened internal controls, reduced waste and downtime, and ensured precise resource utilization (Zhou, Xu et al., 2023). Real-time feedback and analytical tools have enabled firms to avoid unnecessary costs and move toward improved sustainability (Lu et al., 2023; Peng & Tao, 2022). Additionally, DT enhanced financial transparency, easing procurement processes, and alleviating financial constraints (Du et al., 2023; Lin & Xie, 2023). DT enhanced a firm's resource allocation and integration capabilities by boosting knowledge sharing and facilitating niche market expansion (Pang & Wang, 2023; Y. Zhang et al., 2023; Yang & Deng, 2023). Moreover, DT strengthened supply chain resilience. It reduced fluctuations and long-term costs and released resources for firm initiatives (Gao et al., 2023; Yu et al., 2024; Z. Y. Zhang et al., 2023). Real-world example can exemplify this mechanism. Using DT in Faulkner Hayes helped the company optimize resources by reducing labor-intensive tasks. DT allowed the company to save on operational costs, improve customer service, and become an industry leader (IMPACT, 2023).

Collaboration and knowledge amplification mechanismThe sample articles suggested that DT influenced knowledge search and recombination strategies. In an optimistic scenario, DT complemented or replaced existing competencies and knowledge structures, enhancing knowledge search depth, breadth, and recombination (Lanzolla et al., 2021). By breaking down communication silos and facilitating cross-boundary collaboration, DT facilitated knowledge exchange, allowing firms to benefit from diverse perspectives on innovation (Pang & Wang, 2023). McDonald's strategy is a good example of such a mechanism. It involved building a digital newsroom to monitor social media and enable real-time decision-making. These initiatives led to cross-functional team collaborations that drove customers’ innovative engagement (Kane, 2015).

DT is a knowledge exchange platform that promotes co-creation and user-oriented innovation (Y. Zhao et al., 2023). By reducing the time lag between user feedback and organizational response, DT allows real-time analysis of user data to improve offerings (Peng & Tao, 2022). DT's role in real-time analysis and feedback capabilities provided timely insights. These insights allow organizations to adjust their innovation strategies and reduce the time required from idea generation to implementation (Peng & Tao, 2022; van Meeteren et al., 2022). Moreover, DT encourages active user involvement and enables the sharing of expertise and insights. User involvement accelerates the creation of user-centric products and services (Y. Zhao et al., 2023). For instance, McDonald's adoption of mobile payments, self-service kiosks, and real-time social media engagement during the 2015 Super Bowl campaign demonstrated how DT could lead to innovative customer engagement strategies (Kane, 2015). Espinoza's Leather Company also exemplified the knowledge amplification mechanism using paperless order taking, improving communication, collaboration, and cross-team exchanges. This expanded their growth-focused projects by enriching customer engagement (IMPACT 2023). DTs enhance data processing and analytics, and help firms derive actionable insights from vast datasets. These practices increase data-driven knowledge and innovation (Lozada et al., 2023; Yang & Deng, 2023). The cases of Netflix and Amazon further illustrate the effectiveness of this mechanism. They used real-time feedback on user preferences to drive rapid innovation (IMPACT, 2023). Amazon also scaled its business from online bookselling to becoming an e-commerce giant by benefiting from DT to deliver an optimized customer experience and adapt to their needs (IMPACT, 2023; Kane, 2015)

In addition, DT expands firms’ collaborative networks. These collaborations enable firms to explore new opportunities for joint design, development, and delivery of innovative products and services (Lu et al., 2023; Pang & Wang, 2023; Y. Zhang et al., 2023; Zhang & Fan, 2024). Furthermore, DT connects firms to a broader digital ecosystem. This connectivity provides faster and more affordable access to resources for sustained innovation and continuous value co-creation (Che et al., 2023; Urbinati et al., 2020). For example, Under Armour's focus on DT enabled the firm to shape tech-based collaborations, launch fitness apps, and build a vibrant community among customers and the brand (IMPACT, 2023; Kane, 2015)

Financial and risk management mechanismThe sample articles suggested that DT improves firms’ access to financing and could decrease the risks associated with innovation. DT also increases firm transparency and the likelihood of accessing financing for technology upgrades and innovation activities (Lin & Xie, 2023). This transparency reduces information asymmetry. Once asymmetry decreases, it signals the innovation capacity of firms to investors (Du et al., 2023). This could minimize investment delay and ensure that financing is available for the innovation ambitions of firms (Du et al., 2023; Lin & Xie, 2023; Z. Y. Zhang et al., 2023). DT also helps firms move toward high-potential innovations using advanced analytical tools, giving them business ideas, and helping them identify opportunities (Q. R. Liu et al., 2023; Peng & Tao, 2022; Yang & Deng, 2023; Zhou, Xu et al., 2023). Furthermore, DT enhances co-creation and user-centric innovation (Y. Zhao et al., 2023; Peng & Tao, 2022). It decreases the innovation risk associated with supply chain fluctuations by making firms more resilient (Gao et al., 2023). The financial and risk management mechanism aligned with BCG's findings that firms undergoing DT often improve their financing and reduce the direct waste of resources (Forth et al., 2021). In another case, using analytics in Humanyze helped the company incorporate insights from data analytics to plan behavioral changes and mitigate organizational risks by analyzing collaboration patterns (Forth et al., 2021).

Productivity and efficiency improvement mechanismThe sample articles suggest that DT enhances capital productivity and operational efficiency in several ways. For example, it leads to cost savings and improved financial performance (Lu et al., 2023; Yang & Deng, 2023). In addition to saving, by optimizing resource use through real-time analytics and feedback mechanisms, DT frees up financial capital for innovative activities and enhances transparency for investors, thus easing access to financing (Lu et al., 2023). Additionally, DT enhances operational excellence by helping firms monitor assets more effectively to ensure optimal capital utilization (Lin & Xie, 2023). DT also helps internal quality control, reduces waste, and ensures more precise use of resources (Y. Zhao et al., 2023). In addition, impacts data-driven decision-making. Feedback and data-driven analysis reduce unnecessary expenditures toward a more productive organization (Lu et al., 2023; Peng & Tao, 2022). Digitally transformed companies typically employ transparent financial reporting procedures. Increased transparency through credit information disclosure eases financial constraints and smoothens procurement processes (Du et al., 2023; Lin & Xie, 2023). DT also enhances knowledge sharing and market expansion. Therefore, resources can be allocated and integrated more efficiently (Pang & Wang, 2023; Y. Zhang et al., 2023; Yang & Deng, 2023). Finally, DT improves supply chain resilience. This resilience reduces fluctuations, lowers costs, and frees resources for future innovation and growth (Gao et al., 2023; Y. Zhang et al., 2023). As a practical example of this mechanism, Under Armour's use of digital technology to develop customer-centric features and connect physical products to virtual experiences demonstrated how DT-driven improvements in operational efficiency could boost brand value and growth (Forth et al., 2021; IMPACT, 2023).

Moderation effectsAs discussed below, the moderators were categorized based on their effects at different stages of the AMO framework: a) between antecedents and outcomes, b) between antecedents and mediators, and c) between mediators and outcomes.

Moderators: DT–innovation linkagesEnvironmental or contextual moderatorsExternal environmental factors played a significant role in determining how DT benefits innovation in firms. These included market conditions, the maturity of technology, and the level of industry competition. For instance, market turbulence forces firms to use DT to efficiently reallocate resources and reshape their competitive strategies. Wang et al. (2023) highlighted how faster DT helped firms respond to emerging customer demands with ambidextrous innovations. Reduced rent-seeking behavior in a fair-market environment encourages firms to prioritize productive endeavors. Additionally, in turbulent and dynamic markets where information grew rapidly, DT strengthens firms’ information-processing capacities, which lowers unpredictability and increases ambidextrous innovation (X. G. Li et al., 2024).

Firms must be agile in terms of market and technological turbulence by using DT to manage unpredictability and enhance ambidextrous innovation (Jiang et al., 2024; Z. G. Peters et al., 2019; Li et al., 2023). As customer demand evolves and market information becomes more complex, accelerated DT enables firms to allocate resources efficiently, respond to emerging needs, and reconfigure competitive strategies (Lu et al., 2024; Sun et al., 2024). As firms consistently seek to reduce internal innovation costs, government support such as R&D subsidies can help reduce the risks associated with leveraging DT to introduce innovative products and services. Such support can improve resource allocation and access, and enhance the positive effects of DT on innovation (Lin & Xie, 2023; Q. Xu et al., 2023).

Another macro-level variable is the level of market and technological maturity. Y. Zhang et al. (2023) found that when a high level of technological maturity exists in developing markets, product innovations are likely to occur more often than when emerging technologies are in established markets. The latter focuses on innovation efforts toward process improvement. DT increases operational efficiency in highly competitive industries (Chatterjee & Mariani, 2022) and drives radical innovation (Duan et al., 2023; Gong et al., 2023). However, competition can also hinder access to external resources, thus limiting incremental innovation (R. Guo et al., 2023). Firms in highly competitive industries and dynamic markets must strengthen their innovation capabilities and leverage DT to improve their operational efficiency and support exploratory innovation (Xue et al., 2024; Y. Zhang et al., 2023). One of these capabilities is cross-border search capability (CSC). Firms with high CSC can use external resources and technological capabilities to increase their innovation potential through DT (Yao et al., 2023). CSC allows firms to access new resources and technologies that complement internal resources and support resource integration toward innovation.

Managerial attitudes toward digitalization can inspire innovation by promoting digital tools and standards (Xie et al., 2022). Managers’ focus on digitalization encourages an innovation-oriented culture by integrating digital practices and tools across the organization. Finally, regulatory efficiency is important for actualizing DT's innovation outputs. Strict regulations push firms to adopt digital strategies to enhance green innovation (Qiong Xu et al., 2023).

Strategic orientations and capabilitiesThe second moderator category concerned firms’ strategic orientations, affecting how they capitalize on DT for innovation. Firms focusing on novelty-oriented digital innovations outperform those focusing on efficiency-oriented approaches (Shen et al., 2022). An environmental orientation enables firms to incorporate sustainability priorities into their strategies, improve resource efficiency, and lead to sustainable and green innovation (Al Halbusi et al., 2024; Arroyabe et al., 2024; He et al., 2023). This orientation established an environment in which employees were encouraged to share knowledge and develop innovative and resource-efficient solutions (Xue et al., 2024).

In addition to orientation, firm capabilities are important to these dynamics. Sample articles show that high technological capabilities allow firms to effectively absorb new knowledge gained through DT for significant innovation improvements (Zhou et al., 2024). Technological capability refers to a firm's ability to integrate new technological resources and generate new knowledge, which enhances the depth and breadth of accumulated knowledge. Knowledge integration capability further enhances digital innovation by enabling firms to identify innovation opportunities, drive R&D, and increase knowledge heterogeneity (Gong et al., 2023).

Firm characteristicsThe third moderator category is related to specific firm characteristics such as governance models, size, development stage, and managerial capabilities. These categories affect DT's impact on innovation. Governance diversity (gender, education, and board size) positively affects the success of DT in fostering innovation (Lin & Xie, 2023; Wu & Wang, 2024). Larger and more diverse boards provide a wider range of knowledge and expertise. Managers with strong technological backgrounds are better equipped to leverage DT to identify market opportunities and facilitate collaboration (Fang & Liu, 2024; Yang et al., 2023). Family owned firms and those led by technologically proficient top management teams maximize the innovation benefits of DT (Yang et al., 2023). A firm's lifecycle also matters. Growing companies tend to be more adaptable to new technologies and are more likely to benefit from DT than mature firms (Lin & Xie, 2023).

External resources, such as venture capital investments, boost DT's positive impact on innovation (Z. G. Li et al., 2023) by signaling credibility and financial backing to complement DT efforts. The degree of digital industrialization in neighboring regions could either enhance or weaken DT's benefits, depending on whether firms competed or were free-riders on others’ digital advancements (S. L. Li et al., 2023). In regions with high digital industrialization, firms that were free riders on others’ efforts could experience diminished innovation returns.

Moderators: DT–mediators linkagesThis group of moderators either strengthened or weakened the innovation mechanisms discussed earlier. The sample articles showed that entrepreneurial firms enhance information acquisition through DT-enabled interfirm collaborations. The effective orchestration of internal and external resources obtained and accumulated through inter-firm collaborations enables firms to integrate them more effectively toward innovative activities (R. J. Li et al., 2024; Yu et al., 2024). Consequently, high levels of dynamic capabilities facilitate disruptive innovation by improving knowledge acceleration and resource optimization mechanisms (Dionisio & Paula, 2024; Pang & Wang, 2023).

DT also facilitates cross-border knowledge sharing and acquisition, which enhances a firm's open innovation potential. However, the effectiveness of cross-border knowledge sharing and acquisition depends on changes in management practices, such as reorganizing R&D units and initiatives for upskilling and reskilling, which enable open innovation (Urbinati et al., 2020).

Furthermore, DT changes a firm's value-creation logic through business model innovation (Z. Y. Zhang et al., 2023). Firms must be capable of actualizing their value-creation potential through business model innovation, including implementing new ideas, enhancing existing products or services, introducing novel offerings to the market, and improving production or management processes.

Moderators: Mediators–outcome linkagesThese moderators can either intensify or hinder the effects of intermediary mechanisms enabled by DT on innovation and performance. For example, DT's role in sensing and seizing external knowledge for radical innovations was significant (Gong et al., 2023). However, the technological capability of a firm and its resourcefulness could determine how the firm leveraged this knowledge (Zhou, Yang et al., 2023). Agility also played a significant role. High market-capitalizing agility involved more resource optimization, facilitating a firm's fast and appropriate reactions to evolving market needs (Zhu & Li, 2023).

Cognitive computing capabilities (CCC) also contribute to an organization's entrepreneurial potential by supporting data-driven decision-making and promoting innovation. Although DT can facilitate the development of CCC, effectively leveraging these capabilities for innovation may require a unique strategy. An ambidextrous innovation strategy tended to produce stronger results than a strategy focused on a single type of innovation. Factors such as resource access, market turbulence, and competition often dictate strategy choice. Organizations with an ambidextrous approach can enhance entrepreneurial quality through computing capabilities (Duan et al., 2023; Gupta et al., 2023).

User involvement is another significant moderator. Users bring valuable insights and knowledge that enrich product development and enhance organizational learning (F. F. Zhao et al., 2023). In dynamic environments, user participation has a unique value. Firms with strong absorptive capacity can better integrate user insights into their innovative decision-making and make them more market-informed (F. F. Zhao et al., 2023).

Discussion and research agendaThe DT literature is scattered among different disciplines, making it difficult to uncover DT's antecedents, roles, and performance implications. Scholars have used SLRs to create a cohesive body of knowledge on DT in various sectors. A shared interest in these studies is the exploration of how DT enables and transforms industries. Gurzhii et al. (2022) and Guandalini (2022) focused on blockchain and sustainability. Rêgo et al. (2023) and Maroufkhani et al. (2022) offered valuable insights into strategic management and industry-specific applications. Maroufkhani et al. (2022) examined the resource and energy sectors, highlighted the lag in DT adoption, and focused on operational expense reduction. Another category of SLRs explores DT's educational, managerial, and project management aspects. Gkrimpizi et al. (2023) categorized barriers to DT in higher education as environmental, strategic, organizational, technological, people-related, and cultural challenges. Ben Slimane et al. (2022) presented an integrated framework for DT strategy. Several studies have explored the association between DT and other contemporary issues. Dionisio and Paula (2024) investigated the link between DT and eco-innovation technologies that promote sustainability. Another category tends to uncover flexibility and organizational and operational agility. Finally, Hanelt et al. (2021) and Junior et al. (2024) provided comprehensive frameworks for understanding DT's impact on organizational change and business agility.

Although these systematic DT reviews are informative, they often fail to address innovation as an outcome of DT. The complexities of the intermediary mechanisms and intervening contingencies further complicate this understanding.

The framework used in the current research clarifies the mechanisms underlying the DT–innovation interplay and identifies key areas that require attention based on the gaps in our understanding. The following section discusses the research agenda, as summarized in Tables 6 and 7.

Research agenda based on AMO framework components.

| AMO Framework Component | General Direction | Research Gap | Research Directions | Example Research Questions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Further inclusion of new outcomes | Inclusion of new outcomes | - Expand beyond the Schumpeterian-type innovation and organizational performance outcomes of DT &Investigate network and alliance-level performance outcomes. | - How does DT impact platform innovations and stakeholder experiences at the network and alliance levels?- What are the advantages of open innovation facilitated by DT, and how are they realised? |

| Exploring the role of economic structure re-adjustment | The role of economic structure readjustment in fostering innovation outcomes through DT. | How can economic structure readjustment foster innovation opportunities in digital economies? | ||

| Understanding the role of digital economic development | how digital economic development in various regions reshapes the innovation potential of firms and industries. | How does digital economic development influence platform innovations and stakeholder experiences in different regions? | ||

| Understanding social innovations | - Explore DT's effects on social innovations for poverty alleviation or community development. | - How can DT contribute to social innovation to address poverty alleviation or community development? | ||

| Incorporating a design science perspective | - Shift focus from technical and economic aspects of DT to user-centric principles and customer needs. | - How can firms leverage design-centric approaches in DT implementation to address customer needs more effectively? | ||

| Considering the marketing perspective on DT performance | - Investigate DT's role in customer value creation, trust building, and brand reputation. | - How does DT contribute to building trust and brand reputation for value co-creation with customers? | ||

| Antecedents-Outcomes Relationships | Further Emphasising context-specificity of innovation as an outcome of DT | Context-specificity of innovation as an outcome of DT | - Maintain consistency in defining innovation and consider specific contexts.- Explore DT's role in different macroeconomic and organisational environments. | What are the differences in DT's impact on innovation outcomes in high-tech vs. low-tech firms? |

| Value of DT for different categories of innovation | - Investigate the value of DT for various categories of innovation beyond green and sustainable innovations. | How does DT affect the continuity, size, quality, and risk of R&D collaborations? | ||

| Understanding DT-innovation interplay in different contexts | - Study the interplay of DT and its outcomes in various organisational environments and industries.- Investigate geographical differences affecting the DT-innovation relationship. | How do geographical variations in digital infrastructure development impact innovation outcomes? | ||

| Ensuring comparability and consistency of innovation definitions | - Adopt interdisciplinary approaches to understand the multifaceted nature of innovation and its interplay with DT. | What interdisciplinary approaches can enhance our understanding of DT's impact on innovation? | ||

| Economic structure readjustment, particularly in transition economies | Investigate the role of digital economic restructuring in the relationship between DT and various types of innovation, such as green, social, and technological innovations. | How does economic structure readjustment toward digitalization influence the types of innovation enabled by DT in different sectors?How do sector-specific policies in digital economic development shape DT's innovation outcomes? | ||

| Antecedent | Understanding the multi-dimensionality and the context-specificity of DT | Implications of multi-dimensionality and context-specificity of DT on innovation | - Specify conceptual boundaries and definitions of DT in research.- Explore the impact of different conceptualizations of DT on innovation outcomes. | How do different definitions of DT influence research findings on innovation outcomes? |

| Ensuring consistency in conceptualization | - Ensure consistency in defining DT across studies to facilitate accurate comparison and generalization of findings.- Investigate the implications of inconsistent conceptualizations of DT. | What are the consequences of inconsistent conceptualizations of DT for organizations implementing research findings? | ||

| Mediators | Go beyond neoclassical assumptions of resource optimization to explain DT's effect on innovation | Investigation of DT-innovation mediators using behavioral and dynamic perspectives | - Go beyond neoclassical resource optimization assumptions for DT-innovation interplay and adopt behavioral economics theories to explain DT's effects on firm performance outcomes- Investigate dynamic perspectives such as behavioral economics principles and theories on co-creation. | 1. How do behavioral economics principles shape stakeholder participation in DT-driven innovation?2. How do users frame risk and reward when participating in value co-creation in digitally transformed firms?3. How dynamic and strategic firmCapabilities (e.g., agility) enhance the users’ participation in innovation. |

| Moderators | Further investigation of boundary conditions | Deeper investigation of boundary conditions | - Investigate contextual factors related to DT and innovation to generate insights into this interplay.- Explore cross-country and industry-level insights. | How do different levels of digital infrastructure development across countries affect the impact of DT on innovation?What are the sociological and cultural factors within industries that moderate the effects of DT on innovation? |

| Industry-Specific Moderators | - Explore industry-specific factors influencing the relationship between DT and innovation outcomes, including regulatory frameworks, market dynamics, and technological sophistication. | How do regulatory frameworks unique to the pharmaceutical industry moderate the impact of DT on innovation in comparison to other sectors? | ||

| Comparative Analysis of Governance Regimes | - Conduct comparative studies to understand how different governance regimes impact the relationship between DT and innovation. | How do government policies promoting DT initiatives in the United States compare to those in East Asian countries in fostering innovation?How do the regulatory differences between countries affect the effectiveness of DT in driving innovation? | ||

| Temporal Analysis of Moderating Factors | Explore how temporal factors, such as technological advancements and changes in regulatory environments, influence the interplay between DT and innovation over time. | How have changes in regulatory environments impacted the DT-innovation relationship over the past years? | ||

| Regional Disparities as Moderators | Investigate regional disparities in DT-driven innovation, considering factors such as access to infrastructure, resources, and entrepreneurship ecosystems. | How do regional disparities in innovation ecosystems influence the DT-innovation interplay? | ||

| Multi-Level Analysis | Adopt a multi-level analysis approach to examine how factors at different levels (e.g., organizational, industry, regional, national) interact to actualize DT's innovation value.Examine how economic policies promoting DT impact the moderating factors between DT and innovation. Investigate how regional disparities in economic development affect the DT-innovation relationship. | What role do national institutional environments or policies play in moderating the relationship between DT and innovation across different industries?How do government policies promoting digital economic development and infrastructure influence the boundary conditions for DT-innovation outcomes? |

Research agenda based on bibliographic results.

| Research Agenda | Gaps | Future Research Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Addressing Fragmented Research and Interdisciplinary Integration | Fragmented research landscape across disciplines, underrepresentation in strategy and entrepreneurship | Integrate strategic and entrepreneurial perspectives to explore how DT strategies impact entrepreneurial activities and business model innovations. |

| Increasing Geographical and Funding Diversity | Geographical concentration in China, heavy reliance on Chinese funding sources | Include perspectives from underrepresented regions to capture a comprehensive picture of DT's influence on innovation across different cultural and economic contexts. |

| Diversifying Methodological Approaches | Limited adoption of longitudinal approaches, lack of methodological diversity, and need for multi-level studies. | Increase the adoption of longitudinal approaches to understand how DT's performance outcomes, such as innovation, emerge over time. Diversify methodological approaches, e.g., using configurational approaches (Lin et al., 2022; Cortese et al., 2024). Include more multi-level studies. Investigate team-level dynamics, norms, and practices enabling innovation in digitally transformed firms. |

| Integration of Theoretical Perspectives | Lack of integration of theoretical perspectives at different levels, limited consideration of DT's dynamic nature | Integrate theoretical perspectives at macro, meso, and micro levels to better conceptualize and explain firms' innovation outcomes. Consider the dynamic nature of the exchanges between firms and their wider environment beyond viewing DT as merely an innovation optimization function. |

In addition to the directions based on the AMO framework, some general directions can be derived based on the current state of DT innovation literature. The current literature on DT-innovation interplay is dominated by studies on large enterprises in which digital transformation may not emerge as an organization-wide phenomenon because of the technological path dependencies in such organizations and their bureaucratic nature. However, research on the DT-innovation interplay in small and medium enterprises is necessary to understand if and how these firms, as resource-constrained entities, can fully leverage DT to boost their innovative potential. Moreover, the DT-innovation literature requires more industry-specific insights because technological capabilities at the industry level and competitive dynamics are radically different across diverse industries. Many studies have focused on industries traditionally known to be less innovative, but there is a need to focus on industries with high technological turbulence and emergence levels. Healthcare, the mobility sector, retail, 3D, and multimedia are areas with limited research focus. Future research should further investigate the nature, mechanisms, and contingencies of DT-enabled innovation in these sectors. Finally, while the literature on the DT-innovation interplay is dominated by China and emerging markets, focusing on developed markets is important for gaining cross-contextual insights into how macro-level infrastructural differences can affect the innovative outcomes of DT. The below section provides recommendations based on the components of the AMO framework.