Scientific research in digital transformation is expanding in scope, quantity, and relevance, bringing forth diverse perspectives on which factors and specific dimensions—such as organizational structure, culture, and technological readiness—affect the success of digital transformation initiatives. Numerous studies have proposed mechanisms to assess an organization's maturity through digital transformation across various models. Some of these models focus on external influences, others on internal factors, or both. Although these assessments provide valuable insights into a company's transformation state, they often lack consistency, and recent research highlights key gaps. Specifically, many models primarily reflect the views of senior management on the general progress of digital transformation rather than on measurable outcomes. Moreover, these models tend to target large enterprises, overlooking small and medium enterprises (SMEs), which are crucial to economic growth yet face unique challenges, such as limited resources and expertise.

Our study addresses these gaps by concentrating on SMEs and introducing a novel approach to assessing digital transformation readiness—a metric that reflects how prepared an organization is to optimize transformation outcomes. Following design science research methodology, we develop a model that centers on the perspectives of general employees, offering companies an in-depth view of their readiness across 20 dimensions. Each dimension is evaluated through behaviors indicative of the highest level of digital transformation readiness, helping companies identify areas to maximize potential benefits. Our model focuses not on technological quality but on the degree to which behaviors essential for leveraging technology and innovative business models are integrated within the organization.

These days, the discussion of the economic development of any industry is linked to the enormous possibilities that technology can contribute or unlock. The role that technology is playing is not only enabling organizations to continuously develop their structures and models but also creating high levels of disruption in existing business models, putting some of the least prepared companies at significant risk (Quinn, Dibb, Simkin, Canhoto, & Analogbei, 2016; Müller, Buliga, & Voigt, 2018; Santoro, Vrontis, Thrassou, & Dezi, 2018). Digital transformation (DT), a phenomenon that has been widely researched over the past decade, is pushing companies beyond their boundaries and stretching the possibilities of their reach, providing them with the ability to develop new business models and new ways to interact with customers. Above all, it is reshaping their overall way of thinking and operating within their domain (Loebbecke & Picot, 2015; Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). This process of continuously seeking improvements and disruption while embracing the endless possibilities of technology and digital models significantly contributes to greater opportunities for companies, especially in supporting faster growth and international reach (Hair, Wetsch, Hull, & Perotti, 2012). Adopting technology is no longer an optional step for organizations. Rather, it represents a fundamental decision, focused on effectively managing and maximizing its potential benefits (Newman, 2017; Ross, 2019).

When we discuss organizations, economic growth, and technology, it is essential to consider the role of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and their impact on the global economy. SMEs significantly contribute to the gross domestic product (GDP) of various national economies and have an enormous impact in job creation, accounting for more than 50% of employment in most countries (Muller et al., 2017). Still, even though SMEs have a widely acknowledged impact, they have not been the top priority of the research community over the past decade, particularly in the context of digital transformation. This issue is exacerbated by the continuous struggles these organizations face in adopting newer technologies or models supported by those newer technologies (North & Varvakis, 2016; Giotopoulos, Kontolaimou, Korra, & Tsakanikas, 2017; Andriyanto & Doss, 2020). These struggles are highly driven by the limitations these organizations have in resources and knowledge (Ross, 2019; Machado et al., 2021; Zhu, Ge, & Wang, 2021), putting these companies at significant risk of disruption or general failure (Markides, 2006; Maicher, Radic., Dijik & Große, 2016). In an economy where SMEs account for more than 90% of the companies and employ over 50% of the workforce, it is fundamental that those companies seek newer levels of competitiveness by leveraging what technology has to offer and thus maintain or increase their level of relevance to customers (Nerima & Ralyté, 2021).

Given the significant role of SMEs and the widely confirmed benefits of DT in increasing competitiveness levels, we must find strategies that provide some foundational support for these companies. This support is essential to help them fight back against their limitations, mainly because not everything is a problem. SMEs are widely characterized by their flexibility and agility—two factors that play a critical role when there is a need to change or transform (Williams, Gruber, Sutcliffe, Shepherd, & Zhao, 2017; Barann, Hermann, Cordes, Chasin, & Becker, 2019). Additionally, their leaner and flatter organizational structures can facilitate a faster adoption of new technologies and streamline communication, which may significantly contribute to a positive outcome of DT initiatives (Williams et al., 2017; Barann et al., 2019; Prause, 2019). According to the World Economic Forum (2018), over 80% of chief executive officers (CEOs) indicated that a DT program must be implemented. At the same time, by 2030, more than 70% of economic value creation is expected to be based on digital platforms. However, previous research presents a high rate of more than 70% of DT initiatives that fail to reach the expected value, leading to significant financial losses and, more importantly, negatively impacting companies (Tabrizi, Lam, Gerard, & Irvin, 2019). Therefore, one of the critical aspects of DT is a company's ability to change and transform its processes and overall organization (Legner et al., 2017; Parviainen, Tihinen, Kaariainen, & Teppola, 2017). The reasons organizations fail to achieve the expected DT results vary, with a lack of understanding of new competencies and business models playing an important role (Libert, Beck, & Wind, 2016).

SMEs become even more complex as DT introduces a series of risks, some of which lead to significant failures. As noted by Libert et al. (2016), many organizations fail to deliver on their expected outcomes, contributing to financial loss in transformational projects (Libert et al., 2016; Tabrizi et al., 2019). Much of the research in this area has focused on the development of maturity models. These models are designed to evaluate a company's state in terms of implementation, but they vary greatly depending on the factors or dimensions considered by different authors. One of the limitations of these models is the overfocus on the implementation status rather than on what is preventing companies from maximizing the results of the implementation itself. In response to this limitation, recent research (Kane, Palmer, Phillips, Kiron, & Buckley, 2018; Lokuge, Sedera, Grover, & Dongming, 2019) has highlighted the growing importance of assessing a different dimension of DT: readiness. Readiness is not focused on the actual implementation status but rather on a company's preparedness to take advantage of the implementation (Kane et al., 2018; Lokuge et al., 2019; Gfrerer, Hutter, Füller, & Ströhle, 2021). By assessing it, we take a deeper look at how well a company is prepared to achieve the expected results from its DT. Research on readiness may be a step to identifying solutions that address the challenges arising from three main factors: (1) the combination of SMEs lacking capabilities, (2) the need for SMEs to invest in newer technologies and models deriving from those technologies; and (3) the significant percentage of companies that fail to obtain the expected results. The challenge is that there is currently a substantial gap in models that assess readiness and an even larger gap in models specifically tailored to determine readiness in SMEs (Silva, Mamede, & Santos, 2024). Our research aims to significantly contribute to the scientific community by addressing this challenge.

The research carried out by Silva et al. (2024) provides an extensive literature review of 24 existing models related to maturity and readiness. In this study, the authors conduct a thorough analysis of existing models and, through different methods, identify a significant gap in the overall assessment of SMEs. A key issue in determining the perspective to adopt when conducting these assessments is the predominant focus on management perspectives rather than on the perspective of employees. The selected models need more transparency regarding what is required to maximize the results of a transformation. Instead, they focus on assessing how far along the transformation process is, based on the management perspective or external auditing. This review highlights the importance of considering a different perspective, particularly the need to separate the actual maturity of an implementation from the factors and behaviors that may potentially influence its results. This perspective is especially crucial for SMEs which face known limitations and must prioritize maximizing the return on their investments rather than merely assessing them.

Our research is solely focused on SMEs and aims to identify ways to provide a stronger foundation for these organizations to define a plan and take advantage of their DT. We hypothesize that a readiness assessment, especially one that is firmly focused on the employee's perspective, is a pivotal approach to understanding the factors that may prevent an organization's preparedness for adopting necessary changes, thereby maximizing the value obtained. Our research looks at the readiness approach as a more focused concept that concentrates on behaviors that prevent maximum outcomes when not implemented. This study is guided by the following research questions:

- RQ1)

How can an assessment model be designed to assess the readiness levels of SMEs for DT?

- a.

Can the practical case provide enough valuable insights to help SMEs plan their future with technology?

- b.

How can this research help SMEs understand what north star they should pursue to increase their level of readiness?

- a.

- RQ2)

Are there any similar patterns across different SMEs that can be used for further research?

- RQ3)

How do SME leaders and industry experts evaluate and validate the proposed model?

By answering these research questions, we believe our work will not only clarify the distinction between maturity and readiness but also provide an artifact that could introduce important tools for SMEs. This artifact will offer them a level of insight that existing models have not captured, enabling SMEs to be more strategic and precise in the actions needed to drive their DT. Although companies will be better positioned to compete, they will also have more limitations in their capabilities (resources and competencies) when considering a more strategic and focused approach. Through our work, we:

- •

Propose a more formal definition of readiness as a concept focused on behaviors that ultimately impact the outcomes of a DT. This definition is especially relevant because it addresses the need for standardization across the most appropriate existing models, as identified by Silva et al. (2024). Their analysis of key maturity and readiness models revealed that these concepts are often used interchangeably, leading to a need for a more unified view.

- •

Propose a set of target readiness behaviors that define an advanced state of readiness to maximize the results of a DT.

- •

Propose a model called the digital organizational readiness assessment model (DORAM), specifically designed for SMEs, which is entirely focused on the readiness dimension to maximize the results of DT assessments.

- •

Validate our model through an evaluation carried out by a targeted group.

What differentiates our model from previous work is its focus on the type of company that involves a dimension that has not yet been deeply explored: readiness as a set of behaviors. Our model, which is entirely focused on SMEs, assesses readiness by considering the employee's perspective and comparing it to the senior management's perspective, providing a more comprehensive understanding. By combining an innovative approach that considers the perceptions of general employees and senior management regarding a set of target behaviors, our model assesses the company across a wide range of categories and subcategories. This innovative approach equips SMEs with an incomparable toolkit to define their future transformation and, equally important, to maximize the results of their digital journey.

This article presents the major outcomes of our work, being structured into seven main chapters:

- -

Chapter 2 describes the approach undertaken in our work to define the concept of readiness as a set of behaviors that enhance a state of preparedness.

- -

Chapter 3 outlines the methodology used to deliver the proposed DORAM.

- -

Chapter 4 describes the proposed model, including its key assumptions and attributes.

- -

Chapter 5 details the demonstration phase, showing how the model was applied to gain insights across different companies.

- -

Chapter 6 covers the validation and evaluation process of the proposed model, including the actual results obtained.

- -

Chapter 7 summarizes the main conclusions and contributions of our work.

In our research, as presented in Silva et al. (2024), we conducted a detailed analysis of state-of-the-art assessment models in the context of a DT. Our work reviewed 24 models, most of which focused heavily on the maturity aspect of assessments. However, the concepts of maturity and readiness have often been used interchangeably, leading to confusion. These terms have distinct definitions: readiness stands for the state of being ready, as defended by Kane et al. (2018) and Lokuge et al. (2019), whereas maturity is much more focused on the state of implementation, as argued by Leino, Kuusisto, and Paasi (2017). Our analysis of the models reviewed by Silva et al. (2024) revealed that many models combine “state of implementation” and “state of readiness,” which supports our view that there is no clearly defined distinction between maturity and readiness in existing approaches.

The concept of readiness is not specific to DT but is often discussed in organizational contexts. Existing research explores various aspects related to or influenced by readiness, such as trust and commitment (Mangundjaya, Bhayangkara, Raya, & Hutapea, 2023), how adaptability affects readiness (Adam, Hanafi, & Yuliani, 2022), and the impact of leadership in the process of organizational commitment (Runa, 2023). Additionally, studies examine the impact of psychological safety on organizational change and its effect on employees’ readiness for change (Naumtseva & Stroh, 2021), as well as how some organizational strategies such as strategic workshops can play an essential role in enhancing organizational readiness (Roos & Nilsson, 2020). Finally, Weiner (2009) offered a significant contribution to what can be understood as organizational readiness, defining it “as a shared team property, that is, a shared psychological state in which organizational members feel committed to implementing an organizational change and confident in their collective abilities to do so.”

Drawing from the different perspectives on readiness and Weiner's work (Weiner, 2009), which provides a substantial foundation, we can conclude that readiness is more closely related to behaviors than to systems. When we address readiness in DT, we may look at the behavioral dimension that impacts the outcomes. This perspective is a significant contribution to distinguish between the concepts of maturity and readiness.

While reviewing other models, we encountered attempts to address the concept of readiness, such as those by de Carolis, Macchi, Negri, and Terzi (2017) and Machado et al. (2021). However, these models often blur the distinction between readiness and maturity, lacking a clear separation criterion between both concepts. In addition, those cases focus heavily on the readiness level to deploy technology in manufacturing, which ultimately limits their applicability across other industries.

Existing literature often links readiness to behaviors rather than deployment, especially in the context of organizational readiness (Roos & Nilsson, 2020; Naumtseva & Stroh, 2021; Runa, 2023). This work proposes a formal distinction between the traditionally discussed concepts of maturity and readiness. Specifically, readiness is defined as a set of behaviors, which serves as the foundation of our approach.

Table 1 summarizes the proposed distinction between readiness as a set of behaviors and other existing proposals.

Isolating readiness as a concept defined by a set of behaviors.

| Maturity Concept | Existing Readiness Concepts | Proposed Readiness Concept |

|---|---|---|

| The concept of maturity is widely used in maturity models, such as those by Klötzer and Pflaum (2017), & Gimpel et al. (2018), Schumacher, Erol, and Sihn (2016), Leino et al. (2017), Berghaus and Back (2016), Kljajić and Pucihar (2021), Sandor et al. (2021), and Tiss and Orellano (2023). In these models, maturity is typically applied to measure the implementation stage, assessing how far an organization has progressed in specific dimensions defined by the models. This approach often relates to how technology is deployed, how the processes are digitized, or if a proper organizational structure is in place. | The concept of readiness is less widely used than maturity. Still, the existing models, like those of de Carolis et al. (2017) or Machado et al. (2021), often equate readiness with a state of maturity to deploy manufacturing or digital technologies. However, readiness needs to be recognized as a distinct measure with specific dimensions and factors. For instance, de Carolis et al. (2017) measures readiness levels through maturity levels, which conflates the two concepts to a certain extent. In these models, readiness is often interpreted as being finished rather than “being ready to adopt change.” | This model proposes a distinction between the maturity of an implementation (e.g., DT) and the level of readiness (behaviors) required to maximize the results of that implementation. For example, maturity would assess how far a customer relationship management (CRM) platform has been implemented, whereas readiness would assess whether the necessary behaviors to maximize the CRM are present in the organization and to what extent. This formal separation aims to differentiate between implementing something and optimizing it through the adoption of ideal behaviors. |

To develop the proposed model, we followed a sequence of steps that ultimately led to the final proposal presented in this publication:

- 1.

Identifying problems and gaps to tackle: As a base of our work, we began by reviewing existing models and identifying gaps in the literature, as outlined by Silva et al. (2024).

- 2.

Model principles: To tackle the listed problems, we have defined a set of principles that we consider mandatory for our model's success.

- 3.

Categories and subcategories: An assessment model requires assessing a list of categories and subcategories. We used the proposal published by Silva et al. (2024) for that purpose.

- 4.

Target behaviors: Recognizing that readiness levels are significantly influenced by a set of behaviors, we reviewed the models published by Silva et al. (2024) and defined the target behaviors for each subcategory.

- 5.

Readiness levels and dimensions: We then designed the readiness levels and dimensions that impact progress, using the defined categories, subcategories, and target behaviors.

- 6.

Assessment process: We developed a process to assess the readiness levels of companies across all subcategories/categories, incorporating perspectives from senior management and general employees.

- 7.

Assessment questionnaire: We designed a questionnaire to support our assessment process.

The overall approach, part of a broader research project on the digital organizational readiness of SMEs, follows design science research (DSR) methodology and the framework provided by Peffers, Tuunanen, Rothenberger, and Chatterjee (2007), as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Instantiation of DSR described by Peffers et al. (2007).

Silva et al. (2024) research involved an extensive literature review, examining the different models that fit the criteria of assessing maturity or readiness in the context of DT.

In their published work, the authors identified four apparent research gaps:

- -

There needs to be a clear focus on readiness assessment models, especially considering the proven scientific knowledge that readiness for change is critical to maximizing change successfully.

- -

More efforts are needed to develop readiness models for small and medium enterprises, given their substantial presence in the number of active companies, workforce size, and contributions to countries’ GDP.

- -

There needs to be more focus on considering the difference in perspective between general employees and senior management regarding readiness for change. There is strong evidence that understanding these differences in perspective and tackling the differences play a vital role in successfully implementing change.

- -

No standardized set of factors (dimensions) is used across the research community to define what aspects should be evaluated regarding maturity and readiness in DT.

The details of the approach are summarized in Table 2.

Methodological Details.

| Phase | Description |

|---|---|

| Problem identification | Problem identification is carried out through a detailed literature review to determine whether the predefined problem is accurate and to ensure it has not already been solved in other published works. In our application of the DSR model by Peffers et al. (2007), we conducted a systematic literature review to identify specific gaps, which were substantiated through a scientific review process, as detailed by Silva et al. (2024). |

| Objectives | Based on the problem to be solved and the identified gaps, we defined a set of objectives to guide our research. These objectives, presented in this article, formed the basis for developing our model. |

| Design and development | In line with the identified problems and objectives, we defined the following set of components for our model:

|

| Demonstration | The demonstration phase is designed to put our model into practice and gather insights from its execution. In our case, we conducted a demonstration with 12 companies, all of which met the SME criteria and represented various aspects of SMEs. The details are provided in Section 5 of the article. |

| Evaluation | Following the DSR approach, we thoroughly conducted an evaluation phase to assess the quality of the outcomes produced by the proposed model and, most importantly, to validate the designed model and its key decisions. The details of this validation are provided in Section 6. |

| Communication | All outcomes from the DSR process will be communicated to the industry. In this case, the results were published in Silva et al. (2024) and in this article. |

We designed our research questions to help close the identified research gaps. The relevance of SMEs and their impact on the global economy, combined with the need to maximize the benefits of DT, makes these research gaps highly relevant. Our work follows DSR to develop a user-friendly model that supports SMEs enterprises assess their readiness for DT, focusing on the employee perspective. We selected DSR because it is a problem-solving approach aimed at enhancing human knowledge, developing innovative artifacts, and solving problems (Peffers et al., 2007). Within the DSR, we selected the model proposed by Peffers (Peffers et al., 2007) because it is a widely consensual design science methodology. The main reason for this selection is its simplicity. Although it emphasizes the theoretical review during the transition from objective to design more than Hevner's approach (Hevner, March, Park, & Ram, 2004), it better suits the current research. This approach is especially suitable because readiness is not a well-defined, tangible asset to investigate in the SME environment. At the same time, it provides a practical and highly problem-oriented, objective-centric, and solution-oriented process, guiding us from problem identification (and relevance) to the design, development, demonstration, and communication of a solution.

Proposed readiness assessment modelIn our research, we identified the gaps in DT assessments, and the data revealed that there is little to no investment in readiness assessments, particularly in the context of SMEs. We also concluded that the concept of readiness was widely used in similar meanings of maturity, leading to confusion and misunderstandings. Our work proposes a clear distinction, defining readiness as a concept that specifically focuses on behaviors required to enable organizations to make the best out of digital technologies and business models, ensuring they remain competitive.

To address the lack of resources, knowledge, and tools in SMEs, we developed the DORAM. In this chapter, we will present the different components of the model and how they can be applied to any SME.

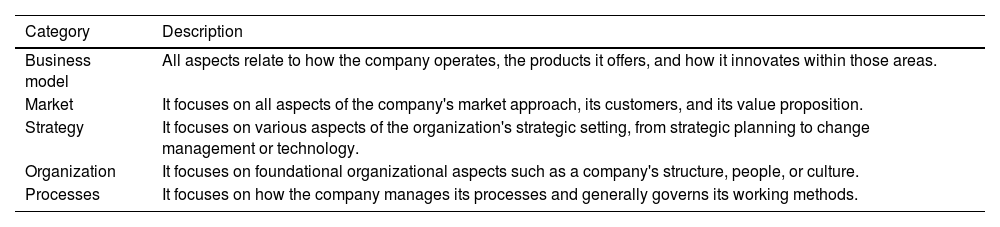

Categories and subcategoriesAfter defining the principles, we needed a clear set of factors/dimensions/categories to serve as the basis for our assessment. These elements should comprehensively represent all aspects that influence a company's ability to perform at its best.

In the work carried out by Silva et al. (2024), they publish a formal proposal for the categories and subcategories that should be used to develop new assessment models. Their proposal is based on an extensive literature review and an analysis of existing models. These categories normalize more than 80 categories/dimensions used across most assessment models. Because we refer to that review throughout our research, we adopted these proposed categories as the base for our proposed model. They are listed in Tables 3 and 4.

Readiness categories (adapted from Silva et al., 2024).

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Business model | All aspects relate to how the company operates, the products it offers, and how it innovates within those areas. |

| Market | It focuses on all aspects of the company's market approach, its customers, and its value proposition. |

| Strategy | It focuses on various aspects of the organization's strategic setting, from strategic planning to change management or technology. |

| Organization | It focuses on foundational organizational aspects such as a company's structure, people, or culture. |

| Processes | It focuses on how the company manages its processes and generally governs its working methods. |

Readiness subcategories (adapted from Silva et al., 2024).

| Category | Subcategory | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Business model | Business structure | How does the company adapt and understand business models to apply to customers? |

| Products and services | How does the company understand product management and digitalization as a core component of it? | |

| Innovation | How does the company embrace innovation as a mindset and leverage data to achieve better results? | |

| Market | Customers | How does the company manage its relationship with customers? |

| Value Proposition | How is the company shaping its value proposition? | |

| Go to market | How is the company managing its approach to the market? | |

| Strategy | Strategic planning | How does digitalization embed in the overall strategy, and how does the organization allocate the right resources? |

| Change management | How does the company manage change and embed change management practices? | |

| Transformation | How does the company understand transformation as something that must be managed? | |

| Organizational strategy | How does the company strategize to enable the organization to meet the digital challenge? | |

| Technology | How does the company embed technology in its day-to-day operations? | |

| Organization | Organizational structure | How clear is the organizational structure? |

| People | How is the company developing its talent to meet new demands coming from DT? | |

| Culture | How is the culture being adapted to new ways of working? | |

| Collaboration | How does collaboration work across the organization? | |

| Leadership | How does leadership play an influential role in driving the right behaviors? | |

| Operations | How are operations adjusting ways of working? | |

| Processes | Process management | How standardized are the business processes? |

| Monitoring and control | How well managed are the processes? | |

| Governance | How is the company looking at governing the different initiatives and processes? |

By establishing these five categories and 20 subcategories, we have set a solid base to deepen our understanding of how an organization should perform at its best to maximize its DT results. However, we still need to define the specific behaviors that companies should target. Defining these behaviors is the next step in designing the model.

Target behaviors of each subcategoryTo be able to provide an assessment, we need to know what we are measuring, and more than having the categories (and subcategories), we need to define the target. Hence, we have designed a process to obtain the required target behaviors.

Building on the systematic literature review published by Silva et al. (2024), we have reviewed all the models and analyzed all the dimensions and factors used by each model to assess the maturity of the organizations. As noted by Silva et al. (2024), most models must fully distinguish between maturity and readiness. Therefore, we have applied our proposed definition, summarized in Chapter 2, where maturity is viewed as assessing the implementation status by focusing on initiatives aimed at deploying something, whereas readiness is defined as the set of behaviors that indicate a company's preparedness to maximize its DT results.

We have yet to identify any clear and well-defined proposals for readiness target behaviors, which is aligned with a lack of research in this area. As a result, we set out to propose these target behaviors, relying heavily on previous research. Instead of inventing new behaviors, we reviewed the models analyzed by Silva et al. (2024) and followed this process:

- 1.

Assess the different dimensions identified as the end state proposed by each model.

- 2.

Classify each dimension as either “maturity” or “readiness” based on our proposal of what readiness is.

- 3.

Extract all the different readiness dimensions and characteristics from other models.

- 4.

Map all the extractions using our categories and subcategories.

- 5.

Summarize all the findings into a set of target behaviors that define a target state of readiness.

In Table 5, we summarize the different models we reviewed and the core behaviors we defined as a state of higher readiness.

Target readiness behaviors based on the literature review.

| Subcategory | Target behaviors | Reference models/literature |

|---|---|---|

| Business structure |

| |

| Products and services |

| |

| Innovation |

| |

| Customers |

| |

| Value proposition |

| |

| Go to market |

| |

| Strategic planning |

| |

| Change management |

| |

| Transformation |

| |

| Organizational strategy |

| |

| Technology |

|

|

| Organizational structure |

| |

| People |

| |

| Culture |

| |

| Collaboration |

| |

| Leadership |

| |

| Operations |

| |

| Process management |

| |

| Monitoring and control |

| |

| Governance |

|

With the target behaviors summarized in Table 5, we have an excellent baseline for designing a model that assesses an organization based on these targets. However, referring to one of the principles of the model that “It must be simple enough for any SME to be able to utilize it,” we still lack a format that could be presented to employees and senior management to allow them to give their assessment. Rather than presenting a list of bullets described as “behaviors,” we have converted those behaviors into what we call the “behavior north star”. These are user-friendly statements that summarize the different target behaviors and can be presented to the other profiles as a target state for the company.

Table 6 summarizes the proposed north stars for each subcategory, consolidating the proposed target behaviors into a more approachable format.

Proposed behavior north star.

| Subcategory | Target behaviors | Target north star |

|---|---|---|

| Business structure |

| The company must adapt to newer business models to fully leverage the technologies it has implemented. At the same time, companies must keep exploring different models to sell their products to existing or new customers. |

| Products and services |

| The company must adapt to the digital economy and adjust its offerings to focus more on digital-centric and data-driven products and services. |

| Innovation |

| The company must recognize data as one of its critical assets and continuously foster a mindset of innovating new models, ideas, or products, especially with a clear focus on incorporating more digital technologies into those ideas. |

| Customers |

| The company must center its approach on its customers by (a) embedding insights, (b) improving relationship management, (c) personalizing that relationship, and (d) guaranteeing the trust needed to build a long-term relationship. |

| Value proposition |

| The company must be clear on its value proposition to its customers and how to adjust that proposition based on newer technologies and data. |

| Go to market |

| The company defines clear customer interfaces and continuously monitors market trends and competitor actions. It leverages new technologies and channels, such as social media, while optimizing and scaling its marketing practices. |

| Strategic planning |

| The company must define a clear and well-articulated digital strategy with a plan for execution that aligns with its mission and objectives. It must ensure that the IT strategy is a vital component of the overall company strategy and that the necessary resources are allocated to achieve it. |

| Change management |

| The company must manage change according to its complexity, implement the necessary processes for adoption, and ensure that a change management mindset is present at all levels to effectively adapt to that change. |

| Transformation |

| The company must treat transformation as a project that requires management, guaranteeing that adequate management support and performance management are critical components. |

| Organizational strategy |

| The company must be agile and flexible, adapting to external and internal changes. It should foster a robust digital mindset, adopt new technologies, and create a goal-oriented, motivational culture. |

| Technology |

| The company must guarantee a reliable IT infrastructure, invest in new technologies and data for its key processes, and ensure technology is embedded in everyday activity, with a strong focus on cybersecurity and data privacy. |

| Organizational structure |

| The company must have a clearly defined organizational structure that is transparent to all employees. It should create an environment where employees are empowered to achieve results through a lean, results-oriented structure. |

| People |

| The company must clearly define what skills and competencies are needed to succeed in any role, promote the continuous development of its talent, guarantee that digital competencies are core to the organization through sustainable learning practices, and build the mindset and skills needed to win in a digital environment. |

| Culture |

| The company must foster a positive attitude toward newer technologies, value the role of technology, promote knowledge sharing across teams and partners, and develop an environment that embraces adaptability and is ready to take risks. |

| Collaboration |

| The company must guarantee a healthy environment that promotes knowledge sharing among peers, cooperation with partners, collaboration between departments, and team spirit and flexibility. |

| Leadership |

| The company must guarantee that senior managers lead the example in promoting digital technologies and mindsets. They must be role models in the transformation process, promote open communication, advocate risk-taking attitudes, and be committed to making a difference. |

| Operations |

| The company must make its operations flexible to adapt to external volatility. Ideally, they should be highly automated and decentralized, with continuous improvement practices in place. The company should also manage its suppliers effectively, with strict reporting on finance and overall management. |

| Process management |

| The company must implement transparent and fully standardized business processes that are entirely digitally enabled and trustworthy for all employees. |

| Monitoring and control |

| The company must automate its business processes to enable efficient, transparent, data-driven decision making and establish the necessary processes and controls for correct business monitoring. |

| Governance |

| The company must deploy efficient project and portfolio management practices, establishing transparent cost and revenue control practices, all connected through standardized and documented management practices around performance, results, planning, or strategy. It must also guarantee consistent data governance across the organization. |

The different north stars summarized in Table 6 will be used to create a user-friendly questionnaire that any employee can use in an SME to assess, based on personal perception, how close the company is to achieving the target state.

Readiness levels and measuring dimensionsOne of the required decisions while designing the assessment model is defining its number of levels. We have yet to identify any relevant literature that unanimously defines the appropriate number of levels. Based on the comprehensive review of existing models by Silva et al. (2024), the most common number of levels is four or five levels. Because one of our principles was to maintain simplicity and usability for SMEs, we have opted to identify four levels.

The definition of these levels was highly influenced by the Capability Maturity Model Integration (Goldenson, Gibson, & Ferguson, 2004), which supported our work in defining how the levels should be represented.

Our proposal consists of the following levels (illustrated in Fig. 1):

- 1.

Immature (Red): The company does not demonstrate the key target behaviors and has limited to no actions to address them.

- 2.

Unstructured (Orange): The company sometimes demonstrates critical behaviors and may be evolving toward a more structured level.

- 3.

Structured (Yellow): The company often demonstrates key behaviors and is potentially evolving toward an advanced level.

- 4.

Advanced (Green): The company consistently demonstrates key behaviors, measures them, and continuously improves based on defined actions.

One of the principles of our model is its visual approach. We have applied a color code to each level to facilitate an understanding of the assessment results. In this case, red represents the lowest level, and green represents the highest (as illustrated in Fig. 2).

To compute a readiness level, we had to define which dimensions would contribute to that calculation, assuming that each subcategory's “end state” is determined by the target behaviors and north stars summarized in Tables 5 and 6.

Based on the literature (Weiner, 2009; Roos & Nilsson, 2020; Naumtseva & Stroh, 2021; Adam et al., 2022; Runa, 2023), we can identify that behavior tends to be more sustainable when it occurs frequently and is less random. In other words, behaviors that are more frequent and consistent are considered more effective. Therefore, we have selected two key dimensions for our assessment: the frequency of the behavior and how it is managed. We then used these dimensions to break down the different levels (1—10) using the Likert scale (Joshi, Kale, Chandel, & Pal, 2015). As illustrated in Fig. 3, we mapped how each level corresponds to these two dimensions.

As illustrated in Fig. 3, progression can occur vertically or horizontally. Horizontal progression happens when a behavior becomes more frequent, whereas vertical progression indicates that the behavior is better managed (less accidental). The transition between Levels 6 and 7 represents the most considerable step in our model, primarily because the organization would move from an unstructured to a structured readiness level, marking a major milestone in the consistency of target behaviors.

This definition of the levels and dimensions provides a clear path for companies to follow, indicating that the further a company is from Level 10, the more it is lagging in achieving the target behaviors for a specific subcategory (as illustrated in Fig. 4). In our proposal, we consider the assessment in terms of behaviors to be driven at the subcategory level. This approach is necessary because a company may be more ready in one subcategory, such as customers, than another, such as going to market; hence, if we evaluate at a higher level, it could be too generic and less actionable for determining next steps.

The designed approach is fully tailored to provide the company's leadership with a perspective on how far they are from achieving the target behaviors, based on their employees’ perceptions. This approach helps them identify the key aspects they will focus on when thinking and planning for improvements needed in the organization.

Readiness assessment processThe process to assess readiness is designed to be straightforward and applicable to SMEs and, hence, must consist of a series of simple steps that can be executed regardless of whether the company has five employees or 300 because both would potentially fall within the SME category.

The proposed model, DORAM, uses a questionnaire as the basis for assessment (more details in the next chapter). This questionnaire allows employees and senior management to assess how they perceive their company regarding the target behaviors (in terms of frequency and management).

We designed a process that consists of five steps:

- I.

Meeting with senior management: Before any execution, a 30- to 45-minute meeting with the senior management team will explain how the model works and what is being assessed. During this session, senior management should agree to distribute a questionnaire to all their employees via corporate email, and to complete the questionnaire themselves.

- II.

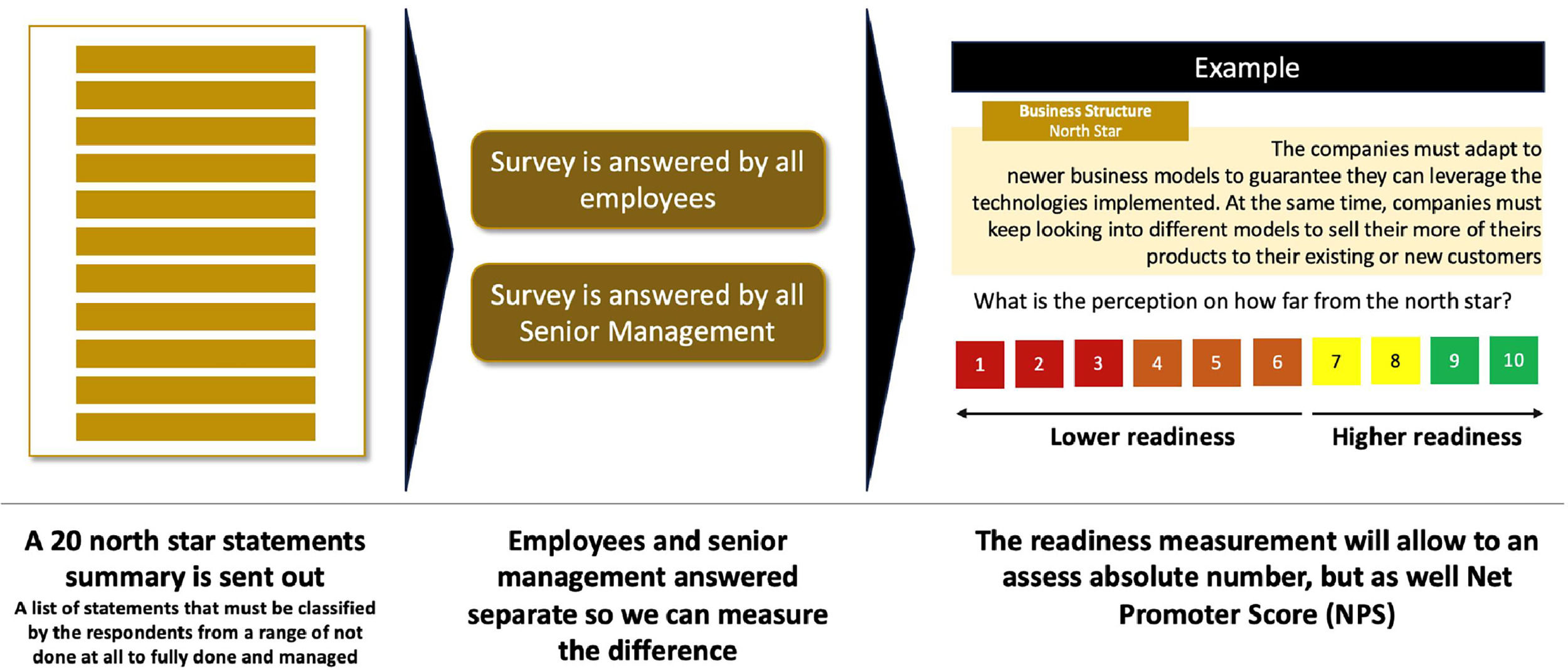

Questionnaire distribution: A questionnaire with the 20 north stars is sent to all employees and senior management (illustrated in Fig. 5). This procedure allows us to collect the perspectives from both employees and senior management.

- III.

Compute and calculate readiness at the subcategory level: After collecting the responses from all the employees and senior management, we calculate the following four measurement indicators:

- a.

Average rating at subcategory level for employees: This provides an overall rating based on employee responses.

- b.

Average rating at subcategory level for senior management: This provides an overall rating based on the senior managers’ responses. From this, we can calculate the Perception Gap.

- a.

Perception Gap (Pg) = IF (Employee Rate > Senior Management Rate) THEN (Employee Rate > Senior Management Rate) ELSE (Senior Management Rate - Employee Rate).

As referenced in the literature (and illustrated in Fig. 6), differences in perspective between employees and senior management create a more significant risk of change adoption and require more efforts in baselining a common understanding as a preliminary step toward changing behaviors (Voß & Pawlowski, 2019; Gfrerer et al., 2021; Trenerry et al., 2021)

- a.

Median rating at subcategory level for employees: We can calculate the readiness level when removing the outliers, providing an excellent benchmark compared to the estimated average rating.

- b.

Net Promoter Score (NPS): The NPS provides a clear view of the difference between employees who could be considered detractors (a rating of 6 or less) and those who can be regarded as promoters (a rating of 9 or 10). The approach is illustrated in Fig. 7.

- a.

- %1.

Presentation of the results to senior management: Based on the four different measurements, provide a comprehensive report to senior management explaining the highest and lowest subcategories, the most significant perception gaps, and the overall distribution of responses.

- %1.

Assessment of the results: After the results are presented, senior management should complete a questionnaire that asks for their evaluation.

Through these four steps, we designed an approach that suits any organization. It allows them to assess the readiness levels of employees versus senior management and, simultaneously, helps understand the distribution of detractors versus promoters in the different subcategories. The NPS approach is necessary because it addresses behaviors and perceptions. Increasing the number of promoters is an excellent step to improve readiness and, more importantly, gain greater buy-in for the organization's transformation.

Questionnaire and approachAs illustrated in Fig. 8, we have designed an approach that supports the overall assessment, based on 20 questions focused on the north stars.

One of the critical decisions in this process was determining the type of rating we would ask employees to provide. To make this decision, we reviewed our initial model principles and set some critical considerations for our decisions related to the approach (summarized in Table 7).

Considerations for design principles.

| Theme | Objective | Design principle consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Granular | It must precisely measure the different factors, breaking them down to the smallest level dimension. | The designed questions should cover at least 20 subcategories and allow conclusions to be drawn at this level of granularity. |

| Behavioral | It must assess and focus on the behaviors related to maximizing the DT. | The questionnaire must focus on the identified target behaviors and north stars. |

| Employee centered | It must be centered on the employee's perspective while also considering the differences from the senior management perspective. | The questionnaire must be completed by any employee with a corporate email address within the organization. |

| Quick | It must be executed quickly and without disrupting the organization's employees. | Considering the organization's lack of resources, completing the questionnaire should take little time. |

Taking full consideration of the defined north stars (see Table 6), the designed principles aligned with four of the model principles, and the two measurement dimensions (see Fig. 3), we developed an approach that engages employees (and senior management) using common language rather than numeric ratings. We recognized that the general population may relate more strongly to answers connected to their daily activities rather than to subjective numerical ratings.

Therefore, as illustrated in Fig. 8, we created a series of statements, termed as “assessment levels,” that provide the employees with a word-based answer in a language familiar to the employees’ daily activities.

The 10 statements are divided into two categories: Frequency and Managed. Each statement covers the two measurement dimensions we defined and provides an exact positioning within the chart illustrated in Fig. 3. These 10 statements allow employees to rate each question using simple, everyday language. The second part of the questionnaire involves questions that employees (and senior management) need to rate, based on the proposed north stars (see Table 5).

We summarize our questionnaire approach in three simple steps:

- 1.

Each question corresponds to one of the 20 north stars.

- 2.

Employees and senior management are asked how they perceive that “vision” within their organization.

- 3.

Each employee and manager select one of the 10 statements to describe their perception of that north star within their organization.

As part of the questionnaire, we provide a clear introduction that explains the meaning of each of the 10 statements (summarized in Table 8) so that employees can resolve any questions.

Assessment level explanation.

| Level | Objective | The explanation given in the questionnaire |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | We are not doing it at all | It is not something I can identify in the company. |

| 2 | We are not doing it, but we have heard of it | It is not something I can identify in the company, but it is something I hear about at times. |

| 3 | We are not doing it, but we talk about it | It is not something I can identify within the company, but it is a topic where I feel actively involved in discussing it. |

| 4 | We do it at times but not actively | I can identify some of it at times, but not in a way that seems structured or planned. |

| 5 | We do it often but not actively | I can often identify it in the company, but I feel it is a lot more random than planned. |

| 6 | We do it often and actively think about it | I can often identify it in the company, and I feel it is being discussed more actively. |

| 7 | We do it almost constantly and discuss it | I can almost always identify it in the company, and I feel it is being actively discussed. |

| 8 | We do it almost constantly and plan it | I can almost always identify it in the company, and I feel it is being actively discussed and planned. |

| 9 | We do it continuously and plan it | I can always identify it in the company, and I feel it is being actively discussed and planned. |

| 10 | We do it continuously, planning it and monitoring it | I can always locate it in the company, and I think it is being actively discussed, planned, monitored, and assessed. |

Each statement (see Table 8) grows in frequency and level of planning, providing natural guidance on which level employees should choose when they rate the 20 north stars. We aim to obtain an almost immediate response (meeting the “quick” objective) that accurately describes their perception of a specific statement in the context of their work at the company.

Artifacts produced as outputs of the assessmentThe last component of our assessment is the “assessment report,” which should be comprehensive and visually intuitive. It aims to provide companies with the right level of insights into which areas may need more active development or where significant perception gaps exist, potentially raising higher risk levels.

We have designed a report that consists of four blocks:

- 1.

General overview: Provides a general overview of participation and average calculations at the category level.

- 2.

Management cockpit: A one-pager that presents the calculations of the four indicators at the subcategory level: employee-based readiness calculation, management-based readiness calculation level, perception gap, and net promoter score.

- 3.

Heatmap: Displays the total distribution of responses, with color coding applied (from red to green) to show senior management how their employees’ perceptions are distributed across the different statements.

- 4.

Health check: A double-click focused view of the highest-rated and lowest-rated areas, as well as the most significant perception gaps.

The initial step in our demonstration and exploratory study was selecting the companies we wanted to include in our research. Our objective was not to conduct a nationwide survey but instead to apply the DORAM in enough companies to demonstrate its applicability. At the same time, we aimed to conduct it across a diverse group of companies, varying in industry and size, to create a solid baseline for extracting insights that could later be used for larger-scale studies or for developing further hypothesis-driven research in SMEs.

To make this selection, we identified a set of criteria to determine whether an organization could be included. These criteria are summarized in Table 9.

Selection criteria for demonstration and exploratory study.

| Dimension | Description | Reasoning |

|---|---|---|

| SME | The company must be categorized as an SME according to the national regulatory criteria. | Our research is entirely focused on SMEs. |

| Size | The company must have between 10 and 300 employees. | The company must be large enough to provide meaningful data but not so large that managing the study becomes overly complex. |

| Structure | The company must have a clearly defined management team. | One of our model's dimensions is assessing the gap between employees and senior management. |

| Commitment | The company's leadership must be fully committed to running the whole process. | The model requires some level of commitment from management to collect the data and review the assessment. |

| Diversity | The selected companies must be allowed to test in different industries. | By running in different industries, we can better compare the data. |

Using the criteria in Table 9, we invited several organizations that met these requirements. Invitations were sent through different channels, including email, LinkedIn, and direct contact. They outlined our study's target and highlighted the potential benefits for companies that participate in the assessment.

Based on these criteria, we then designed a process for each selected company to follow:

- 1.

We sent an official written invitation, asking if they would be interested in participating in our study. We informed them that, by accepting, they would consent to the anonymous use of their data and agree to be fully engaged in the process.

- 2.

Upon acceptance, we scheduled a 30- to 45-minute introductory video call that was structured as follows:

- a.

Introduction of the model and an overview of what to expect (and what not to expect)

- b.

Q&A session

- c.

An outline of the next steps

- a.

- 3.

If management remained interested, we agreed to share two links to two identical online questionnaires: one for all employees and one for senior management.

- 4.

Senior management used their internal processes to send out an internal communication inviting all employees with corporate email to access and complete the employee questionnaire as part of the assessment for their readiness level. Each company allowed at least one week for responses and sent a reminder in the middle of this period.

- 5.

At the end of the response period, the report was generated and the following actions were taken:

- a.

A video call was organized to walk the senior management through the results.

- b.

A pre-read package was sent in advance containing three documents: (1) An explanation of the model and how to interpret the results; (2) The report detailing the actual results of the assessment; (3) A compilation of open-ended comments given by employees during the survey to three general questions “What are you most proud of?”, “What are you least proud of?”, and “What support do you think is needed?”.

- a.

- 6.

A video call session was held to present the results to senior management and to address any questions they had.

- 7.

A results evaluation questionnaire was sent out post-video call, and senior management provided their evaluation.

The presented process was executed with all participating companies, and the results are presented later. The final list of companies is summarized in Table 10.

Companies selected for the demonstration and exploratory study.

| Id | Company label | # Employees | Industry | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Company A | 200 | Advisory Services | |

| 2 | Company B | 100 | Advisory Services | Operating through a franchising model |

| 3 | Company C | 80 | Healthcare | |

| 4 | Company D | 80 | Healthcare | |

| 5 | Company E | 40 | Advisory Services | |

| 6 | Company F | 10 | Manufacturing | |

| 7 | Company G | 50 | Retail | |

| 8 | Company H | 40 | Retail | |

| 9 | Company I | 25 | Manufacturing | |

| 10 | Company J | 20 | Logistics | |

| 11 | Company K | 40 | Logistics | |

| 12 | Company L | 50 | Logistics |

The list summarized in Table 10 presents 12 companies selected across five industries: advisory services, retail, logistics, manufacturing, and healthcare. At least two companies, ranging from 10 to 300 employees, were chosen from each industry.

Once the final list of 12 companies was determined, the study was divided into four phases, as illustrated in Fig. 9.

Each of the four phases has a clear target and defined scope, aiming to standardize the model's execution.

- A)

Introduction: The DORAM is based on many different aspects and requires some commitment from the organization to achieve its objectives. During the introduction phase, a meeting is held with the company's senior management. During that meeting, a comprehensive description of the model and the expectations for the execution phase are given. Expectations are set, and the commitment is once more re-affirmed.

- B)

Execution: During the execution phase, the companies handle the process without external support. The DORAM questionnaire is distributed to all the companies and their senior management. Each company chooses how to share the questionnaire, but it is crucial that it reaches all employees with corporate email access.

- C)

Collection: The results are processed when all the employees and senior management respond to the questionnaire. They are interpreted in two different contexts: (1) In a single company focus report that looks at the company-specific data and (2) an overall study with the 12 companies, extracting the relevant insights.

- D)

Presentation: As soon as the report is completed, a meeting is organized with each company's senior management to present the results. The focus is on the artifacts of the four primary produced models. During this session, there will be an open dialog so the results can be understood within the company's context, and valuable information for developing future action plans will be provided.

Our research involved a comprehensive demonstration of the model, successfully executing it across the 12 selected companies (see Table 10). The participation rates were notably high across all companies, as summarized in Table 11.

Employee participation rate.

| Id | Company label | # Employees | Industry | Responses (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Company A | 200 | Advisory Services | 156 (78%) |

| 2 | Company B | 100 | Advisory Services | 81 (81%) |

| 3 | Company C | 80 | Healthcare | 60 (75%) |

| 4 | Company D | 80 | Healthcare | 77 (97%) |

| 5 | Company E | 40 | Advisory Services | 29 (73%) |

| 6 | Company F | 10 | Manufacturing | 9 (90%) |

| 7 | Company G | 50 | Retail | 43 (86%) |

| 8 | Company H | 40 | Retail | 30 (75%) |

| 9 | Company I | 25 | Manufacturing | 21 (84%) |

| 10 | Company J | 20 | Logistics | 15 (75%) |

| 11 | Company K | 40 | Logistics | 33 (83%) |

| 12 | Company L | 50 | Logistics | 46 (92%) |

With 100% of the companies achieving more than 70% of employee participation, surpassing our 60% threshold, we have a good view of each company.

ResultsFig. 10 summarizes each company's assessment in each subcategory based on their employee rate.

Fig. 10 shows a different set of levels across the companies. For example, company B scores significantly higher than the remaining companies, and company H and F have the lowest scores.

Additionally, Customers is consistently the highest-ranked subcategory across the different companies, with Value Proposition also showing a similar trend. This pattern indicates that SMEs are externally focused but exhibit varying readiness levels when looking at the more internal subcategories. Process Management, Monitoring and Control, and Governance consistently show lower rates/scores. However, similar patterns can also be seen in some subcategories, such as Change Management or Transformation.

Fig. 11 presents the same assessment from the senior management perspective.

Although not the case in all categories, senior management's view tends to be greener and yellower than the view presented by the employees.

This conclusion is supported by Fig. 12.

Fig. 12 shows the perception gaps calculated by comparing the senior management and employee rates. We identify any perception gap above 1 point as red, representing a specific level difference. Only two companies, 17%, are completely aligned across all subcategories. In contrast, 50% of the companies show a perception gap greater than 1 point in at least 40% of the subcategories.

The results in Fig. 12 also support the idea that Customers and Value Propositions are the primary focus for SMEs. In this case, Strategic Planning, Monitoring, and Control also reflect an aligned perception. The difference between the two groups is that Customers and Value Propositions align more at a higher rate, while the latter aligns more at a lower rate.

In total, nine subcategories have a perception gap greater than 1 point in at least 40% of the companies. Notably, Innovation, Transformation, Operations, and Governance represent a perception gap in 50% of the companies, making this gap particularly significant.

One of the other indicators we extract from DORAM is the NPS, and the results of this are summarized in Fig. 13.

The general results indicate that the NPS is negative across almost all companies (75%).

Companies B and L are exceptions because they show consistently positive NPS across all the subcategories. Interestingly, they also show that NPS is closely connected to readiness levels because companies B and L also show the highest readiness levels. This pattern is observed in Company G, which shows marginally positive or medium-high NPS in almost all subcategories.

Standard deviationIn Fig. 14, we summarize the standard deviation for each company in each subcategory and calculate the minimum and maximum values for at least one subcategory. Overall, the standard deviation varies between 1.1 and 3.1 in different subcategories. We also observe that the standard deviations for Innovation, Change Management, Collaboration, Leadership, and Operations are minimal and nearly uniform across all companies. Conversely, Value Proposition, Transformation, Technology, and Culture exhibit the greatest variability, particularly for Value Proposition, Technology, and Culture. This variability is largely due to higher maximum values relative to the median in these subcategories, with differences ranging from 0.7 to 0.9.

Regression analysisDue to the consistent high ranking of the subcategory Customers in terms of readiness levels and NPS, we performed a regression analysis to explore its relationship with the other subcategories. The results are summarized in Table 12.

Regression analysis of customers.

| Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | 95% Confidence interval for B | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | B | Beta | Standard error | t | p | Lower bound | Upper bound |

| (Constant) | 0.79 | 0.19 | 4.05 | <0.001 | 0.4 | 1.17 | |

| BUSINESS STRUCTURE | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 1.89 | .06 | 0 | 0.15 |

| PRODUCTS & SERVICES | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 1.58 | .115 | -0.02 | 0.16 |

| INNOVATION | -0.02 | -0.02 | 0.05 | -0.51 | .614 | -0.12 | 0.07 |

| VALUE PROPOSITION | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.04 | 11.52 | <0.001 | 0.4 | 0.57 |

| GO TO MARKET | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 4.15 | <0.001 | 0.09 | 0.24 |

| STRATEGIC PLANNING | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.25 | .806 | -0.09 | 0.11 |

| CHANGE MANAGEMENT | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 1.19 | .233 | -0.04 | 0.16 |

| TRANSFORMATION | -0.04 | -0.04 | 0.05 | -0.72 | .472 | -0.13 | 0.06 |

| ORGANIZATIONAL STRATEGY | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 1.24 | .217 | -0.04 | 0.15 |

| TECHNOLOGY | -0.01 | -0.01 | 0.04 | -0.18 | .86 | -0.08 | 0.07 |

| ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 1.3 | .193 | -0.02 | 0.12 |

| PEOPLE | -0.07 | -0.08 | 0.05 | -1.6 | .111 | -0.16 | 0.02 |

| CULTURE | -0.04 | -0.04 | 0.05 | -0.82 | .414 | -0.15 | 0.06 |

| COLLABORATION | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 1.34 | .18 | -0.03 | 0.13 |

| LEADERSHIP | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.55 | .582 | -0.06 | 0.1 |

| OPERATIONS | -0.08 | -0.08 | 0.05 | -1.61 | .108 | -0.17 | 0.02 |

| PROCESS MANAGEMENT | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.58 | .56 | -0.07 | 0.12 |

| MONITORING & CONTROL | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 2.5 | .013 | 0.03 | 0.23 |

| GOVERNANCE | -0.02 | -0.03 | 0.04 | -0.54 | .588 | -0.11 | 0.06 |

The regression analysis results indicate that Go to Market, and Value Proposition each have a p-value less than 0.001, and Monitoring & Control has a p-value of 0.013. Because all p-values are below the 0.05 significance level, it can be concluded that the coefficients for these variables are different from 0 in the population. Among them, Value Proposition shows the highest standardized coefficient with a value of 0.49, indicating the most significant influence.

Together with Customers, Value Proposition consistently ranks highest in readiness levels and NPS (and lowest in gaps). Hence, we conducted a similar regression analysis to understand its relationship to the remaining subcategories. The results are summarized in Table 13.

Regression analysis of value proposition.

| Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | 95% confidence interval for B | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | B | Beta | Standard error | t | p | Lower bound | Upper bound |

| (Constant) | 0.31 | 0.17 | 1.79 | .073 | -0.03 | 0.66 | |

| BUSINESS STRUCTURE | -0.03 | -0.03 | 0.04 | -0.96 | .34 | -0.1 | 0.04 |

| PRODUCTS & SERVICES | -0.01 | -0.01 | 0.04 | -0.16 | .876 | -0.09 | 0.07 |

| INNOVATION | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 3.62 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.24 |

| CUSTOMERS | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.03 | 11.52 | <0.001 | 0.32 | 0.45 |

| GO TO MARKET | 0.09 | 0.1 | 0.04 | 2.61 | .009 | 0.02 | 0.16 |

| STRATEGIC PLANNING | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 1.86 | .063 | 0 | 0.17 |

| CHANGE MANAGEMENT | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 1.27 | .206 | -0.03 | 0.14 |

| TRANSFORMATION | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.5 | .618 | -0.07 | 0.11 |

| ORGANIZATIONAL STRATEGY | -0.02 | -0.02 | 0.04 | -0.55 | .583 | -0.11 | 0.06 |

| TECHNOLOGY | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.8 | .421 | -0.04 | 0.09 |

| ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE | -0.07 | -0.08 | 0.03 | -2.24 | .026 | -0.13 | -0.01 |

| PEOPLE | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 3.85 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.24 |

| CULTURE | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.4 | .692 | -0.07 | 0.11 |

| COLLABORATION | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.59 | .558 | -0.05 | 0.09 |

| LEADERSHIP | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.16 | .875 | -0.07 | 0.08 |

| OPERATIONS | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.28 | .78 | -0.07 | 0.1 |

| PROCESS MANAGEMENT | 0 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.01 | .99 | -0.08 | 0.08 |

| MONITORING & CONTROL | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 1.7 | .09 | -0.01 | 0.17 |

| GOVERNANCE | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.24 | .813 | -0.07 | 0.09 |

The results in Table 13 indicate that Innovation, Customers, Go to Market, Organizational Structure, and People are the subcategories with p-values < 0.05.

The regression analysis results indicate that Innovation, Customers, and People each have a p-value less than 0.001, Go to Market has a p-value of 0.009, and Organizational Structure has a p-value of 0.026. Since all p-values are below the 0.05 significance level, it can be concluded that the coefficients for these variables are different from 0 in the population. Among them, Customers shows the highest standardized coefficient with a value of 0.38, indicating the most significant influence.

In a similar analysis, we examined the subcategories of Change Management, Transformation, and Operations, which are at the low end of the readiness assessment in the different analyses.

In Table 14, we summarize the regression analysis results for Change Management.

Regression analysis of change management.

| Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | 95% confidence interval for B | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | B | Beta | Standard error | t | p | Lower bound | Upper bound |

| (Constant) | -0.17 | 0.17 | -1.04 | .298 | -0.5 | 0.16 | |

| BUSINESS STRUCTURE | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 1.03 | .306 | -0.03 | 0.1 |

| PRODUCTS & SERVICES | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.89 | .371 | -0.04 | 0.11 |

| INNOVATION | 0 | 0 | 0.04 | -0.08 | .933 | -0.08 | 0.08 |

| CUSTOMERS | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 1.19 | .233 | -0.03 | 0.11 |

| VALUE PROPOSITION | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 1.27 | .206 | -0.03 | 0.13 |

| GO TO MARKET | -0.05 | -0.05 | 0.03 | -1.51 | .131 | -0.12 | 0.02 |

| STRATEGIC PLANNING | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 4.09 | <0.001 | 0.09 | 0.26 |

| TRANSFORMATION | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.04 | 9.96 | <0.001 | 0.31 | 0.47 |

| ORGANIZATIONAL STRATEGY | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 4.26 | <0.001 | 0.09 | 0.25 |

| TECHNOLOGY | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.44 | .657 | -0.05 | 0.08 |

| ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE | -0.03 | -0.04 | 0.03 | -1.12 | .263 | -0.09 | 0.03 |

| PEOPLE | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.44 | .657 | -0.06 | 0.09 |

| CULTURE | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 2.07 | .039 | 0 | 0.18 |

| COLLABORATION | -0.01 | -0.01 | 0.03 | -0.36 | .721 | -0.08 | 0.05 |

| LEADERSHIP | -0.02 | -0.03 | 0.03 | -0.72 | .473 | -0.09 | 0.04 |

| OPERATIONS | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 2.77 | .006 | 0.03 | 0.19 |

| PROCESS MANAGEMENT | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.65 | .517 | -0.05 | 0.1 |

| MONITORING & CONTROL | -0.06 | -0.06 | 0.04 | -1.45 | .149 | -0.15 | 0.02 |

| GOVERNANCE | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.97 | .334 | -0.04 | 0.11 |

The regression analysis results indicate that all examined subcategories have significant coefficients. Strategic Planning, Transformation, and Organizational Strategy each have a p-value less than 0.001, Culture has a p-value of 0.039, and Operations has a p-value of 0.006. Because all p-values are below the 0.05 significance level, it can be concluded that the coefficients for these variables are different from 0 in the population. Among them, Transformation shows the highest standardized coefficient with a value of 0.39, indicating the most significant influence. The remaining subcategories exhibit smaller influences, with coefficients of 0.16, 0.17, 0.09 and 0.11.

In Table 15, we summarize the results of the regression analysis of Transformation.

Regression analysis of transformation.

| Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | 95% confidence interval for B | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | B | Beta | Standard error | t | p | Lower bound | Upper bound |

| (Constant) | -0.1 | 0.16 | -0.58 | .562 | -0.42 | 0.23 | |

| BUSINESS STRUCTURE | 0 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.03 | .977 | -0.06 | 0.07 |

| PRODUCTS & SERVICES | -0.09 | -0.08 | 0.04 | -2.25 | .025 | -0.16 | -0.01 |

| INNOVATION | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.81 | .417 | -0.05 | 0.11 |

| CUSTOMERS | -0.02 | -0.02 | 0.03 | -0.72 | .472 | -0.09 | 0.04 |

| VALUE PROPOSITION | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.5 | .618 | -0.06 | 0.1 |

| GO TO MARKET | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.68 | .498 | -0.04 | 0.09 |

| STRATEGIC PLANNING | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 3.14 | .002 | 0.05 | 0.22 |

| CHANGE MANAGEMENT | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.04 | 9.96 | <0.001 | 0.3 | 0.45 |

| ORGANIZATIONAL STRATEGY | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 5.57 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 0.3 |

| TECHNOLOGY | 0 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.02 | .981 | -0.06 | 0.06 |

| ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 1.92 | .056 | 0 | 0.11 |

| PEOPLE | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 1.44 | .149 | -0.02 | 0.13 |

| CULTURE | -0.06 | -0.06 | 0.04 | -1.39 | .164 | -0.15 | 0.03 |

| COLLABORATION | 0 | 0 | 0.03 | -0.01 | .99 | -0.07 | 0.07 |

| LEADERSHIP | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 2.49 | .013 | 0.02 | 0.15 |

| OPERATIONS | 0 | 0 | 0.04 | -0.01 | .988 | -0.08 | 0.08 |

| PROCESS MANAGEMENT | -0.02 | -0.02 | 0.04 | -0.51 | .61 | -0.1 | 0.06 |

| MONITORING & CONTROL | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 1.87 | .061 | 0 | 0.16 |

| GOVERNANCE | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.04 | 2.72 | .007 | 0.03 | 0.17 |

The regression analysis results indicate that Change Management and Organizational Strategy each have a p-value less than 0.001, Leadership has a p-value of 0.013, Governance has a p-value of 0.007, Products & Services has a p-value of 0.025, and Strategic Planning has a p-value of 0.002. Because all p values are below the 0.05 significance level, it can be concluded that the coefficients for these variables are different from 0 in the population. Change Management shows the highest standardized coefficient, with a value of 0.38, indicating the most significant influence.

In Table 16, we summarize the results of the regression analysis of Operations.

Regression analysis of operations.

| Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | 95% confidence interval for B | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | B | Beta | Standard error | t | p | Lower bound | Upper bound |

| (Constant) | -0.18 | 0.17 | -1.06 | .291 | -0.52 | 0.16 | |

| BUSINESS STRUCTURE | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 1 | .317 | -0.03 | 0.1 |

| PRODUCTS & SERVICES | -0.05 | -0.05 | 0.04 | -1.29 | .196 | -0.13 | 0.03 |

| INNOVATION | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 3.03 | .003 | 0.04 | 0.21 |

| CUSTOMERS | -0.06 | -0.05 | 0.04 | -1.61 | .108 | -0.13 | 0.01 |

| VALUE PROPOSITION | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.28 | .78 | -0.07 | 0.09 |

| GO TO MARKET | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 2.26 | .024 | 0.01 | 0.15 |

| STRATEGIC PLANNING | -0.02 | -0.02 | 0.04 | -0.42 | .672 | -0.11 | 0.07 |

| CHANGE MANAGEMENT | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 2.77 | .006 | 0.03 | 0.2 |

| TRANSFORMATION | 0 | 0 | 0.04 | -0.01 | .988 | -0.09 | 0.09 |

| ORGANIZATIONAL STRATEGY | -0.08 | -0.07 | 0.04 | -1.8 | .072 | -0.16 | 0.01 |

| TECHNOLOGY | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.28 | .776 | -0.06 | 0.07 |

| ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1.34 | .182 | -0.02 | 0.1 |

| PEOPLE | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 3.6 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.22 |

| CULTURE | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.43 | .667 | -0.07 | 0.11 |

| COLLABORATION | 0 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.01 | .988 | -0.07 | 0.07 |

| LEADERSHIP | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.03 | 6.72 | <0.001 | 0.16 | 0.3 |

| PROCESS MANAGEMENT | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 3.06 | .002 | 0.04 | 0.21 |

| MONITORING & CONTROL | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 3.8 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.26 |

| GOVERNANCE | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 3.12 | .002 | 0.04 | 0.19 |

The regression analysis results indicate that People, Leadership, and Monitoring & Control each have a p-value less than 0.001, Innovation has a p-value of 0.003, and Change Management has a p-value of 0.006. Because all p-values are below the 0.05 significance level, it can be concluded that the coefficients for these variables are different from 0 in the population. Among them, Leadership shows the highest standardized coefficient with a value of 0.23, indicating the most significant influence.

Descriptive analysisLastly, to understand how the industry segment affects readiness levels, we analyzed the overall results based on the company's industry segment.

Fig. 15 represents the frequency of responses by industry.

Although the advisory services and healthcare industries account for many of the responses, each industry provides a reasonable number of relevant answers for our analysis.

Fig. 16 summarizes the mean readiness rates of all employees, broken down by industry segment.

Considering the segments, the data presented in Fig. 16 offer insights that align with previous data in this research. However, the figure also provides additional data points.

Once again, the data confirm that Customers and Value Propositions are the most advanced behaviors across all segments. In four segments (60%—80%), the rate is above 7, indicating a structured readiness level. As in previous data, People and Culture rank among the top four most advanced behaviors, with 60% of segments also rating above 7 (structured).

The segment-based analysis reveals that Change Management, Transformation, and Governance have the lowest readiness levels across all segments. This finding is further confirmed when we apply the mean of means, which is the segment average.