In today's knowledge-driven business environment, firm innovation hinges on effective knowledge management. Organizations are thus motivated to continuously create and apply knowledge to sustain competitive advantage through innovation. This study investigates how various knowledge management dimensions uniquely impact firm innovation within an integrated framework, examining both linear and non-linear relationships—an approach not previously explored. Using a deductive, quantitative approach, data were collected via an online survey of 437 banking employees, with Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) employed to analyze quadratic relationships. Findings reveal that knowledge creation has an inverted U-shaped relationship with firm innovation, while knowledge application shows a U-shaped relationship. In contrast, knowledge sharing, application, and protection exhibit linear relationships, with knowledge sharing being most impactful in driving innovation within the banking sector. These results underscore that overestimating the impact of knowledge management can be counterproductive, as its dimensions do not consistently follow linear paths. The study offers critical insights for management, particularly in knowledge-intensive industries, to monitor and calibrate each knowledge management dimension's influence on firm innovation for optimal performance.

Research investigating Knowledge Management (KM) is gaining momentum in management literature primarily because of the longstanding view in academia that managing knowledge is the next frontier of competitive advantage in a knowledge-based environment (Sang, 2024). The volume of literature related to KM increased after the pioneering work of Nonaka (1994) and its empirical application by leading organisations, such as Apple, Tata, and Google, for business innovativeness and competitive advantages (Verma & Dixit, 2016). Consequently, during the last few decades, KM has been enriched vertically, diffused horizontally across various management disciplines, and finally developed as a separate discipline in the field of management.

This intense attention to KM was received not only because of its importance as a discipline of management, but also because of its contribution to organisations as a vehicle for change and innovation. The literature argues that without proper knowledge management, firm innovation does not occur or is significantly delayed (Weerasinghe & Dedunu, 2020). For example, in Haute Cuisine and culinary services, symbolic knowledge drives the innovation process, inspiring chefs with creative ideas, whereas synthetic knowledge connects the chef's idea with scientists, while analytical knowledge provides support for subsequent science-based development (Albors-Garrigós et al., 2017). This evidence implies that the proper management of knowledge leads organisations to achieve successful innovation (Liu & Zeinaly, 2021; Yang & Rui, 2009). Thus, the challenge for firms is to recognise correct knowledge and manage it for successful innovation (du Plessis, 2007).

KM and innovation have been an interesting area of investigation over the last few decades. Previous studies have examined KM and innovation (Basadur & Gelade, 2006; du Plessis, 2007; Salehi et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022); product innovation performance (Yusr et al., 2021); business model innovation (Bashir & Farooq, 2019); and, creativity and innovation (Astuti et al., 2022; Qandah et al., 2020); and innovation management (Briones-Peñalver et al., 2020). Together, these studies indicate that the relationship between KM and innovation is complex and context-driven, and that KM dimensions (knowledge creation, sharing, application, and protection) are affected by different factors, resulting in different and unpredictable influences on innovation. For example, Arsawan et al. (2022) emphasise that knowledge sharing is influenced by innovation culture. The extent to which this culture fosters innovation depends on structured space, authorised space, the willingness to innovate, and the interplay between leadership and social conditions (Auernhammer & Hall, 2013). Ritala et al. (2022) find that knowledge protection moderates incremental innovation, although it does not significantly impact radical innovation. Dostar et al. (2014) find that, especially in the banking sector, knowledge from customers has a positive impact on a firm's innovation capability and business operations, whereas knowledge about customers and knowledge of customers have different effects. The investigation by Campanella et al. (2019) into the transformation of tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge found that the dimensions of socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization have different (positive and negative) influences on a bank's economic value creation. The dynamics of KM pose significant challenges when comparing its overall effects on innovation performance.

However, an unsolved question in the literature is how these KM dimensions collectively contribute to a firm's innovation while maintaining their relationships. Ahuja (2002); Bratianu et al. (2020); Yang and Rui (2009) provide a more dynamic view to explain how these relationships become non-linear. Yang and Rui (2009) found a U-shaped relationship between knowledge acquisition and new product creativity and an inverted U-shaped relationship between knowledge dissemination and new product creativity. An examination of rational, emotional, and spiritual knowledge in the decision-making process has also identified this non-linear effect (Bratianu et al., 2020). In particular, this study notes that emotional and spiritual knowledge, especially in structured fields such as finance, plays a peripheral role; accordingly, their influence on decision-making is indirect. Ahuja (2002) emphasises that the relative value of knowledge for innovation diminishes over time when similar knowledge is continuously created and disseminated. Chesbrough and Rosenbloom (2002) emphasise that when knowledge is repeatedly applied within similar contexts, its novelty decreases over time. These findings call for a more dynamic perspective to capture the behaviour of knowledge dynamism, which is crucial for managing knowledge and reducing the arbitrariness of knowledge interventions in firm innovation (Schilperoord & Ahrweiler, 2014). If a firm fails to understand this, it may not fully utilise the value of KM for innovation. Despite the increasing number of studies, the non-linearity of KM dimensions has not yet been sufficiently addressed, leaving a lack of clarity about how these dimensions, both individually and collectively, contribute to innovation within an integrated framework. This study aims to address this gap by advancing the literature on the non-linear behaviour of KM.

This study differs from previous studies in several ways. First, it challenges the conventional belief that KM and firm innovation have a linear relationship and asserts that KM's impact of KM is not always straightforward. This novel perspective sheds light on the non-linear dynamics of KM in innovation. Accordingly, the study shows that the KM dimensions foster innovation in a non-linear fashion, even though their direct impact on business innovation is waning, which is revolutionary. Thus, we underscore the significance of comprehending KM within an organizational framework. Second, in contrast to prior observations (Arsawan et al., 2022; Auernhammer & Hall, 2013; Li et al., 2018; McLeod et al., 2022; Ritala et al., 2022) that considered the individual dimensions of KM in innovation, this study deployed the entire KM construct with its dimensions to comprehend which dimensions should be promoted and which should not. This true nature is not visible when a dimension is isolated or observed.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. A review of the literature is organised around the theoretical basis of the research, followed by the study hypothesis. The research approaches and steps included in the study are organised in the Methodology section. The fourth chapter illustrates the data analysis in detail, and the last chapter provides the implications of the study, followed by future research areas.

Literature reviewInnovationInnovation, defined as the application of new solutions or the redesign of existing solutions to meet novel requirements (Bai et al., 2014), involves a specific skill or capability that distinguishes a firm from its competitors. Innovative firms, such as Apple, Sony, and Google, are more competitive within their industries (Vega et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2022) and actively engage in innovation, foster forward thinking, and continuously redesign value propositions (Bai et al., 2014; Un & Asakawa, 2015). Various theoretical lenses, including open and closed innovation, provider and demand-side innovation, and product and service innovation, as well as analytical levels such as users, individuals, groups, and firms, have been used to explore the concept of innovation (McLeod et al., 2022; Ritala et al., 2018; Vega et al., 2012). These studies indicate that innovation is intertwined with knowledge. Nonaka (1994), a pioneer in KM, asserted that a firm's innovation stems from expanding or renewing its knowledge base by blending existing knowledge with new insights, aligning with the evolutionary economic perspective of innovation, where new knowledge is built upon existing knowledge (Coombs & Hull, 1998). These perspectives emphasise that firm innovation remains within the firm's purview through effective combinations of new and existing knowledge; therefore, knowledge management becomes the driving force behind firm innovation.

Firm innovation becomes incremental when new knowledge integration is contingent on existing knowledge, with innovation involving minor changes in technology, functionality, appearance, and performance (Jugend et al., 2018). Within this framework, innovation is neither a random event nor spontaneous; instead, innovation unfolds gradually through incremental steps in KM. This continual improvement allows the firm to strengthen itself and adapt promptly to changing circumstances (Coombs & Hull, 1998; Kodama, 2017). The opposing view suggests that the integration of novel knowledge, which significantly diverges from existing knowledge, results in breakthrough ideas that lead a firm towards radical innovation (Ritala et al., 2018). Particularly in the banking industry, both forms of innovation often occur across product, process, service, and technology dimensions, benefiting individual firms and the wider community, including stakeholders (Bai et al., 2014; Un & Asakawa, 2015). Drawing on this discussion, the present study focuses on product, process, service, and technology innovation in banks, given that the competitive nature of the industry necessitates simultaneous engagement in these types of innovation compared with less competitive industries.

Knowledge managementKnowledge, a widespread concept in society, reflects an individual's belief about reality (Nonaka, 1994), is derived from personal experiences and education, and resides in a person's mind (Harrington et al., 2019; López-Torres et al., 2019). From the knowledge management perspective, knowledge appears in two forms: tacit and explicit (Nonaka, 1994). “Explicit knowledge” refers to knowledge that is codified in many formats, such as books, magazines, and articles that can be transmitted in formal and systematic ways, whereas “tacit knowledge” refers to knowledge that is deeply rooted in action and behaviour in a specific context, which is blended with personal qualities; therefore, it is hard to formalise and communicate (Nonaka, 1994). Nonaka states that tacit and explicit knowledge can be converted into useful organisational knowledge through socialisation, externalisation, combination, and internalisation (Liu et al., 2019).

Firm knowledge, rooted in the organizational structure and possessed by individual employees, is recognised as a primary source of firm competitiveness and innovation (Sang, 2024). Firm knowledge contributes to and facilitates synergy, proactive learning, and creative problem solving through the unique integration of tacit and explicit knowledge. Developing a distinctive knowledge base and applying such knowledge to organizational performance is critical, especially in a knowledge-based economy where knowledge disparity shapes a firm's competitive position (Tassabehji et al., 2019).

From a scholarly perspective, KM is defined as a mechanism by which organisations access, share, apply, and store knowledge, thereby creating new knowledge and capabilities that sustain innovation (du Plessis, 2007; Weerasinghe & Sedera, 2023). Therefore, KM is a complex process with distinct dimensions. Despite numerous studies on this concept, scholars have not yet reached an agreement on what constitutes KM, primarily because of the varying interpretations of its core functions. For example, some scholars argue that knowledge creation includes both creation and capture of knowledge, whereas many studies treat these as two distinct dimensions of KM (Reza Rasekh et al., 2014; Shu et al., 2012). While enriching the depth and breadth of KM, this diversity in interpretation substantially diminishes the construct's uniformity in the literature, adding extraneous meaning to KM.

Drawing on the core meaning of KM (Nonaka, 1994), the nature of the construct itself (Coombs & Hull, 1998), and recent applications like, Ode and Ayavoo (2020); Shehzad et al. (2022); Ting et al. (2021); Weerasinghe and Sedera (2023), this study identifies four main dimensions of KM: knowledge creation, knowledge sharing, knowledge application, and knowledge protection, using a process lens. These dimensions are widely recognised as the primary functions of the KM process. Technically, the process begins with knowledge creation and concludes with knowledge protection; however, the cyclical nature of KM illustrates that knowledge protection, as the final step, gives rise to new knowledge creation (Coombs & Hull, 1998). The spiral nature of KM promotes exponential growth through the creative application of knowledge for innovation. However, the efficacy of KM in driving firm innovation depends on the relationships between these constructs and their respective dimensions.

Knowledge management and innovation: relationship natureThe long-standing discussion between innovation and KM has demonstrated the vivid nature of these relationships in the literature. Most of these relationships are predominantly linear, direct, or indirect. For example, Ting et al. (2021) state that knowledge-management infrastructure (technology, culture, and structure) and knowledge-management processes (knowledge creation, sharing, and utilisation) both have statistically significant and positive effects on firm innovation performance. Similar KM behaviour has been found for green innovation (Wang et al., 2022). Thus, green KM directly affects a firm's sustainable competitive advantage through green innovation capabilities. However, Shehzad et al. (2022) state that knowledge creation has an insignificant effect on a firm's green product and process innovation compared to the effects of knowledge acquisition, sharing, and application. This study highlights the fact that not all dimensions of KM are equally important to firm innovation, emphasising the need for careful managerial attention in managing knowledge of innovation. However, most current scholarship is still based on the assumption that KM has an increasing return relationship with firm innovation, and this ideology has steered them to explore one side of the relationship (linear relationships).

This assumption is challenged by Bloom et al. (2020) who explain that although research efforts are increasing substantially across fields, research productivity sharply declines over time. This suggests that, in broader terms, knowledge management (with research as the primary form) may yield diminishing returns in practical applications. Regarding new product creativity, Yang and Rui (2009) found a non-linear relationship, specifically a U-shaped link between knowledge acquisition and new product creativity, and an inverted U-shaped relationship between knowledge dissemination and new product creativity. Their study highlights that the impact of KM is not always predictable through a linear function; rather, it may involve a combination of positive and negative effects, with both increasing and diminishing returns.

For instance, consider innovations related to electric vehicles (EVs) in the automobile industry. In the early stages, the industry faced limited knowledge, particularly regarding battery technology, which constrained overall EV innovation of electric vehicles. However, as firms such as Tesla and Toyota delved deeply into new knowledge areas (e.g. lithium-ion batteries), the industry's innovative capacity in electric vehicles surged, demonstrating the increasing returns of KM on innovation. However, this extensive application of KM has now begun to show diminishing returns as the saturation of current knowledge results in only minor incremental impacts on firm innovation relative to investment.

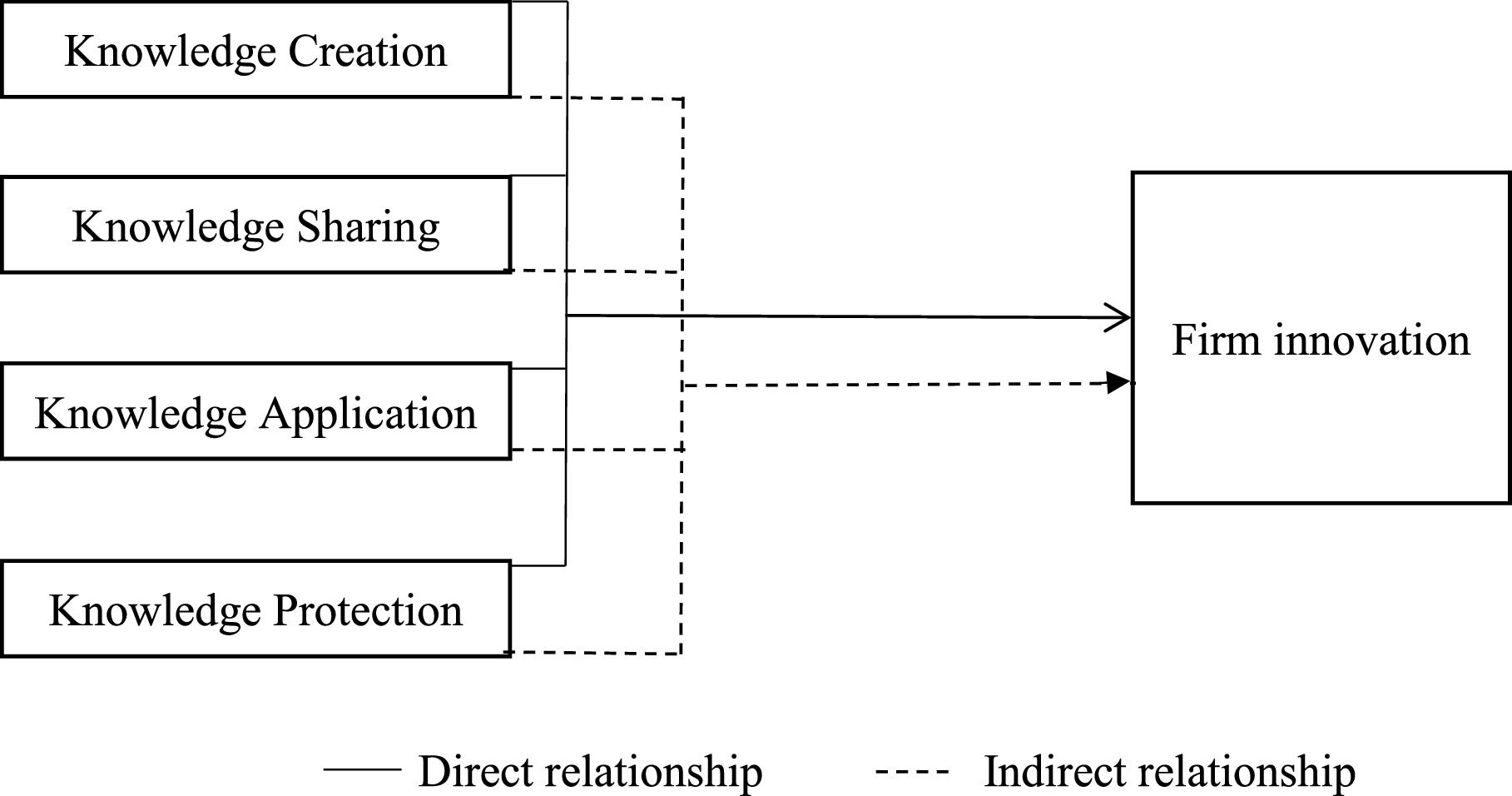

This diminishing return of knowledge was explained by Ahuja (2002) in the context of knowledge sharing. Accordingly, they state that knowledge sharing in its early stages leads firms to achieve significant breakthroughs (radical innovation); however, they note that this effect diminishes over time as firms accumulate similar knowledge. Similarly, Chesbrough and Rosenbloom (2002) emphasise that when knowledge is repeatedly applied within similar contexts, novelty decreases, leading to reduced innovation output. Nambisan and Zahra (2016) explain that knowledge management in the context of opportunity formation is non-linear in complex industries such as the automotive industry because of the intricate, iterative, and dynamic nature of demand-side narratives, which, in turn, influence the non-linear pattern of innovation growth. The literature emphasises that the effect of knowledge management on innovation is dynamic, leading to varying outcomes. Despite the individual effects of knowledge management dimensions demonstrating non-linearity over time, their behaviour within an integrated framework has been significantly overlooked in the context of firm innovation. Accordingly, considering the present relationship between knowledge management dimensions and firm innovation, this study develops a conceptual framework, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Dimensions of knowledge managementKnowledge creation (KC)Knowledge creation entails capturing and developing the necessary knowledge and putting it in a form that may be useful for applications (Alavi & Leidner, 2001). Accordingly, KC has two functions: knowledge capture and knowledge development. Knowledge capture often refers to assimilating or acquiring knowledge from external sources (Zhou & Li, 2012), whereas knowledge development involves the production of in-house knowledge (Alavi & Leidner, 2001). This study incorporated both externally captured and developed knowledge into knowledge creation. In a dynamic environment, new knowledge creation is particularly important, as in many instances, such as technology-oriented consumers, and the existing knowledge of a firm may fall short of meeting the evolving demand in the market, as firms cannot simply imitate or replace knowledge to introduce innovative products (Chang et al., 2014; Olavarrieta & Friedmann, 2008).

Assimilating external knowledge enables a firm to understand existing and prospective market signals that eventually change its natural evolution and path dependencies (Vogel & Güttel, 2012). However, a firm's in-house knowledge generation updates its internal capabilities and competencies, reconfiguring its resource base for external innovative changes (Basadur & Gelade, 2006; Zhou & Li, 2012). Innovation often addresses unmet needs and existing challenges (Wang et al., 2022). KC assists firms in this context in tapping emerging problems in the industry, understanding their root causes, and articulating creative solutions by integrating new and existing knowledge. Therefore, it is possible to anticipate a relationship between KC and innovation (Alshanty & Emeagwali, 2019).

The nature of the relationship between KC and innovation is important for comprehending the dynamism of influence. For example, Papa et al. (2018) identify a positive influence of knowledge acquisition on firm innovation; however, this relationship is moderated by human resource practices. The study notices that a firm innovative climate resulted from HR flexibility and feels employee free to share innovative ideas and visions (Papa et al., 2018). Shu et al. (2012) found that knowledge acquisition is more externally oriented and makes a distinct contribution to firm and product innovation than to process innovation. Yang & Rui, (2009) found that this contribution is not always consistent with firm innovation, with a U-shaped relationship between knowledge acquisition and new product creativity. Considering the relationship between creativity and innovation, it is reasonable to assume that knowledge creation has a linear or non-linear relationship with firm innovation. Accordingly, this study develops the following hypothesis:

H1: The knowledge creation has a significant linear or non-linear relationship with firm innovation.

Knowledge sharing (KS)KS involves the exchange of ideas, experiences, and knowledge among members of an organisation to ensure that the right knowledge is given to the right person at the right time to innovatively perform the right task (Saenz et al., 2012). This is a social process that takes place vertically (among different levels) and horizontally (at the same level) among employees in an organisation, allowing them to critically evaluate existing patterns of work and make necessary alterations for innovative improvements (Raelin, 1998). This comprehensive process minimises work duplication, repetition, and even the cost to the organisation by co-creating novel solutions (Liu & Zeinaly, 2021), and transferring the strategic knowledge required to sharpen firm innovation (Zhao et al., 2020). However, the effect of KS on innovation is controversial because of the quality of shared knowledge and employees’ willingness to engage (Dyer & Nobeoka, 2000; Vaccaro et al., 2010).

The existing literature establishes a solid foundation for understanding the relationship between KS and innovation. Saenz et al. (2012) found that personal-interaction-based KS and knowledge-embedded management processes significantly influenced new idea generation and innovation project management. Zhao et al. (2020) note that both inbound and outbound KS contribute to innovation. While outbound KS fosters innovation directly, inbound KS fosters innovation indirectly. Arsawan et al. (2022) state that KS especially supports small in achieving competitive advantages by creating an innovative culture. Xia et al. (2021) state that when culture promotes task orientation, ICT application, and team disposition in an organisation, collaborative KS becomes more efficient in innovation. The downside of KS is also evident in the literature, which emphasises that finance, insurance, and real estate are major industries in which pseudo-knowledge sharing exists compared to others (Cameron Cockrell & Stone, 2010). The study further emphasises that this negative effect can be ruled out by establishing motivation for knowledge-sharing and providing financial incentives. Martín Cruz et al. (2009) point out that when employees are intrinsically motivated, they tend to engage in KS in the innovation process more than when they are extrinsically motivated. However, Ahuja (2002); Tasi (2001) emphasise that the significant effect of KS on innovation can be seen only at its initial stage because firms become saturated with knowledge when similar information is shared, and then innovation gains diminish. Considering the nature of KS in innovation, this study establishes the second hypothesis.

H2: Sharing of knowledge has a significant linear or non-linear relationship with firm innovation.

Knowledge application (KA)KA, the utilisation of knowledge gained through KC and KS (Ahuja, 2002), is the core of KM, as knowledge per se does not bring any value to anyone without its proper application. Thus, KA is the true use of knowledge for the betterment of an organisation. Knowledge is put into action by an agency (e.g. an employee or, in rare instances, technology such as a chatbox, Siri, or an automated system). It integrates vivid knowledge from various sources in a distinctive manner. (Shin et al., 2001). Thus, organisations must have systems in place to acquire the correct information and mechanisms to deploy information aligned with the organisation's goals and objectives (Almuayad et al., 2024).

KA is an innovative problem-solving mechanism which distinguishes a firm from its rival through innovative knowledge applications. The diversity of KA brings about different outcomes through a similar set of knowledge inputs depending on the context, environmental dynamics, and efficacy of application (Almuayad et al., 2024) allowing the firm to gain a sustainable competitive advantage. Consequently, knowledge is invaluable without proper application (Almuayad et al., 2024). In particular, Eisenhardt and Martin (2000) state that resources are inert and management needs to act upon them to have an effect. This perspective emphasises that innovation emerges through the proper application of knowledge by management (Li et al., 2009; Ode & Ayavoo, 2020). Innovation is inherently linked to risk, and the application of new knowledge for innovation involves uncertainty, often resulting in unpredictable outcomes (Allen, 2013). Concening KA, Ahuja (2002) emphasise that firms that apply existing knowledge to innovate often initially achieve high returns. However, as knowledge is repeatedly applied within similar contexts, novelty diminishes, leading to a diminution in the return on KA. Similarly, Chesbrough and Rosenbloom (2002) found a diminishing return on KA in product development. Based on the existing discussion, the third hypothesis was developed as follows:

H3: Knowledge application has a significant linear or non-linear relationship with firm innovation.

Knowledge protection (KP)KP refers to the extent to which firms employ specific processes to govern and safeguard proprietary knowledge (Nielsen & Nielsen, 2009; Norman, 2002). Previous research has contended that knowledge should be stored and managed in future applications. Most KM literature advocates KP under intellectual property rights (IPRs) (Bhukta, 2020; Branstetter et al., 2006; Olander et al., 2014; Oliver & Sapir, 2017; Samaniego, 2013), including contracts, patents, trademarks, and copyrights. However, obtaining IPRs for all types of knowledge, particularly operational, is impractical. The focus of this study is not to protect knowledge using intellectual property; rather, it focuses on safeguarding (e.g. documenting, internalising knowledge to culture) current knowledge (tacit and explicit) for future applications. Knowledge preservation maintains a firm's distinctiveness and facilitates knowledge transfer across generations (Olander et al., 2014).

KP enhances firms’ ability to forge novel solutions to emerging challenges (Lee & Choi, 2003). It transcends past knowledge and lays a strong foundation for firm innovation (Ode & Ayavoo, 2020). Despite breakthrough innovations, most incremental innovative solutions are grounded in past or present knowledge bases. Therefore, effective KP is crucial for continuous innovation. Ode & Ayavoo (2020) found that KA has a significant effect on firm innovation. Despite firms employing different KP measures to become competitive in inter-firm innovation, extending cultural values and firm policies present challenges (Donate & Guadamillas, 2010). Ritala et al. (2022) also state that KP negatively moderates renewal capital and firm incremental innovation. However, in the long run, excessive reliance on patent protection can limit firms’ external collaboration and knowledge flow (Arora & Ceccagnoli, 2006), thereby slowing firm innovation and diminishing the returns of KP. Building on this foundation, we develop our fourth hypothesis:

H4:Knowledge protection has a significant linear or non-linear relationship with firm innovation.

MethodologyStudy context population and the sampleAs a rapidly developing industry in the service economy, the implementation of efficient KM has become essential for financial institutions to ensure competitive value creation, while protecting their innovative potential (Campanella et al., 2019). The dynamic nature of product structures, industry competition, and increased consumer knowledge has challenged banks’ traditional roles, pushing them to innovate in their knowledge applications (Dostar et al., 2014; Sang, 2024). Banks have become hotspots of innovation for new products, services, and technological applications. KM in banks has been increasingly emphasised owing to financial institutions’ susceptibility to various risks, such as credit default, market volatility, and operational breakdowns, all of which necessitate effective knowledge management (Sang, 2024). Against this backdrop, this study focuses on the banking industry.

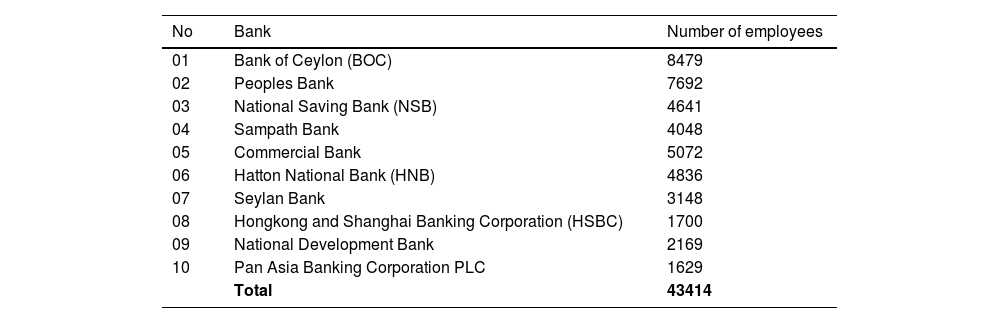

This empirical study is based on the Sri Lankan banking industry, a well-established knowledge-intensive industry. A firm becomes knowledge-intensive when it invests significantly in R&D or skilled labour (Yang & Rui, 2009). Most Sri Lankan banks maintain in-house R&D and ongoing collaboration with universities/external research institutes (Weerasinghe & Sedera, 2023), as well as adopting a special recruitment scheme to directly absorb skilled graduates from universities. The industry consists of 24 licenced banks, and we targeted the top ten banks in terms of service capacity. We excluded banks that operated only in regional areas and those that operated only in the capital city. Accordingly, our online survey targeted employees from 10 selected banks (annexure: 01). The sample size was determined using the PLS-SEM sampling matrix and Morgan table. The PLS Matrix requires 70 employees (Joseph F. Hair et al., 2016), whereas the Morgan table requires 382 employees (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016). With a 50 % response expectation, we conducted an online survey using official employees’ WhatsApp groups. We approached the regional bank management and asked them to distribute our survey to selected branches. The survey began in the first week of September 2022. The first reminder was given a week later, followed by a second reminder after two days through the same channel. To prevent redundancy, a message stating, “Ignore this message if you have already contributed to the survey form” was presented. To confirm the representativeness of the sample relative to the population, an analysis of non-response bias was conducted. However, no significant differences were identified between those who responded at the beginning compared to those who responded at the end.

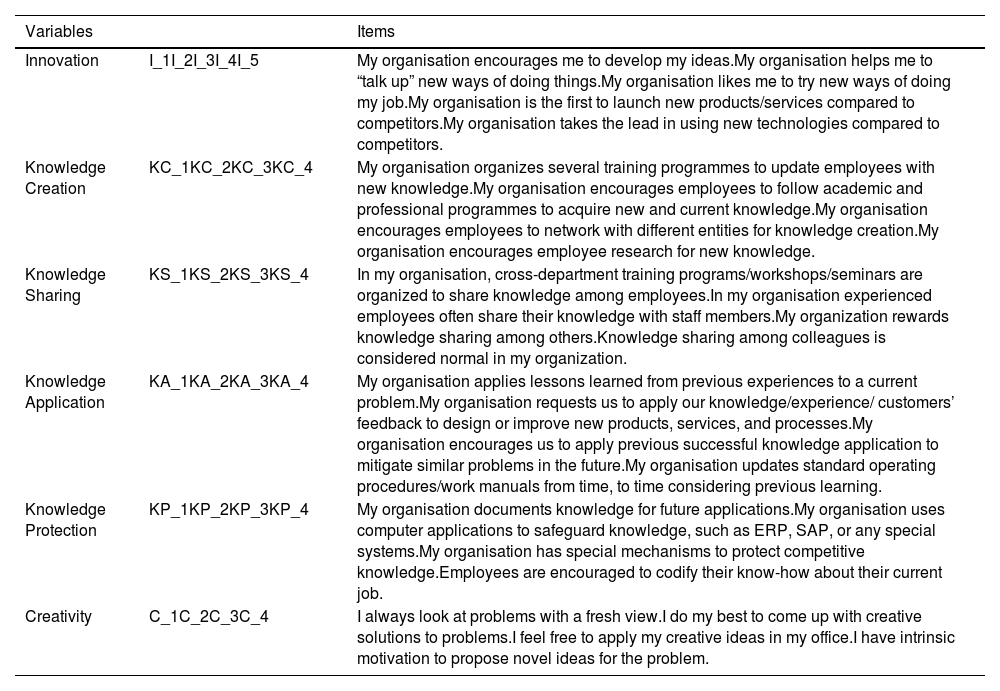

Measurement of variablesThe study deploys already validated scales to measure four items each for KC (Ting et al., 2021; Yang & Rui, 2009), KS (Liu & Zeinaly, 2021; Zhao et al., 2020), KA (Kim & Lee, 2010), and KP (Manhart & Thalmann, 2015; Olander et al., 2014), and five items for innovation (Liu & Zeinaly, 2021; Zhao et al., 2020) with slight modifications considering the banking industry, target audience, and expert suggestions. Expert suggestions were received by sending a questionnaire to senior researchers in the field. The scale ranged from one to seven. The 32 finalised items are listed below the respondents’ fatigue statistics (Dassanayaka et al., 2022).

Control variablesThis study controlled for employee creativity, age, and gender. Creativity has a significant influence on firm innovation, whereas employee age and gender affect innovation through accumulated experience and willingness to take risks (Giustiniano et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2019). Thus, controlling for these effects helps determine the real effect of KM on firm innovation. The study uses the creativity scale of Kim and Lee (2010) and measures it using four items on a seven-point scale, where employee gender (0 = male, 1 = female) and age are measured by discrete values.

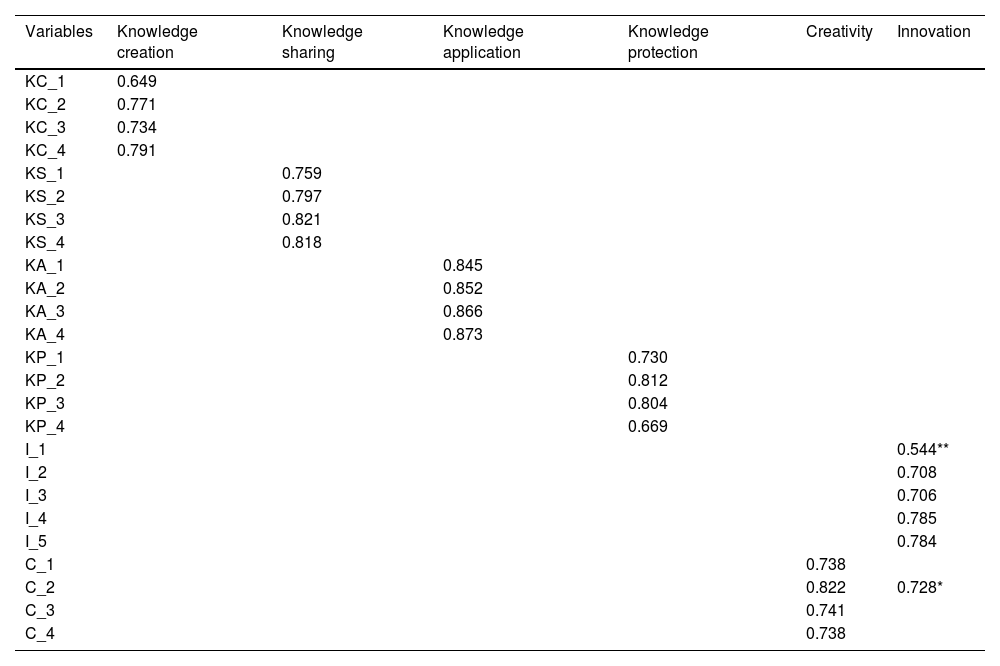

Treatment for common method biasThe study used Podsakoff et al.'s (2003) recommendations to prevent a possible common method bias when collecting data from one informant. Hence, we differentiated measurement scales for predictor and criterion variables, safeguarded respondent anonymity, mitigated evaluation apprehension through diverse questions, and enhanced scales by (a) maintaining simplicity, specificity, and conciseness in the questions; (b) excluding vague concepts; (c) eliminating double-barrelled questions; and (d) clarifying ambiguous or unfamiliar terms. A common method bias arises when one factor accounts for the majority of the covariance in the dataset (Reio, 2010). Our confirmatory factor analysis confirms that there are six distinct categories of variables in the dataset (annexure 02), a common method bias problem in the dataset is most unlikely.

Analysis and discussion of the resultsThe collected data were rigorously cleaned before analysis (Joe F. hair et al., 2020). This involved addressing patterned responses, incomplete submissions and missing data. Patterned responses were removed to prevent potential disruption of the genuine effects of the dataset. Missing values were handled by substituting them with the means of the responses (Joe F. hair et al., 2020). In total, 437 completed responses were included in the final analysis. Post-cleaning, the box plot examination revealed no outliers. Skewness and excess kurtosis values fell within the -1 to +1 range, with slight exceptions for KP_2 and F_2. Thus, we inferred that the dataset was normally distributed and suitable for inferential analysis. In terms of the sample characteristics, responses were predominantly from the Bank of Ceylon (21.7 %), followed by the People's Bank (19.5 %), and the least from HSBC Bank (1.6 %), indicating a higher response rate from government-sector banks compared to private-sector banks operating in the country. The majority (66.1 %) of respondents were aged between 26 and 35 years and held bachelor's degrees (38.5 %). This age group reflects the actively engaged workforce segment, which is likely to have considerable experience and growth potential in their roles. Non-managerial level respondents constituted 59 % of the sample, with a predominance of males (57.9 %). This may influence the study outcomes by emphasising the perspectives of male-dominant operational employees over strategic-level employees.

Measurement model evaluationThis study employed a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) approach utilising Smart PLS software. Our selection of Smart PLS was based on several reasons. First, Smart-PLS is a powerful approach for examining complex models that involve the relationships between latent variables, moderators, and mediators (Noonan, 2017). Second, Smart-PLS is recommended for larger sample sizes (Latan, 2018), and the sample size should be large enough to exceed the minimum PLS-recommended sample size. Third, it provides advanced features (e.g. quadratic relationships and importance-performance maps) and is highly applicable to prediction-focused research (Noonan, 2017). As this study includes a complex model, a larger sample, and a quadratic analysis, we contend that Smart-PLS is an appropriate choice for the objectives of this study.

Our analysis comprises two stages: (1) the development of the measurement model and (2) the development of the structural model. The measurement model dictates the latent constructs of the structural model (Hanafiah, 2020). A reflective measurement approach was applied to the measurement model, emphasising that items in the questionnaire are influenced by their respective latent constructs, and any alteration in a latent construct requires a corresponding change in the respective items (Hair et al., 2020). To assess the reflective measurement model, this study followed the seven steps outlined by Hair et al. (2020). These steps encompass: 1. estimation of loadings and significance; 2. indicator reliability; 3. composite reliability; 4. average variance extracted; 5. discriminant validity; 6. nomological validity; and 7. predictive validity.

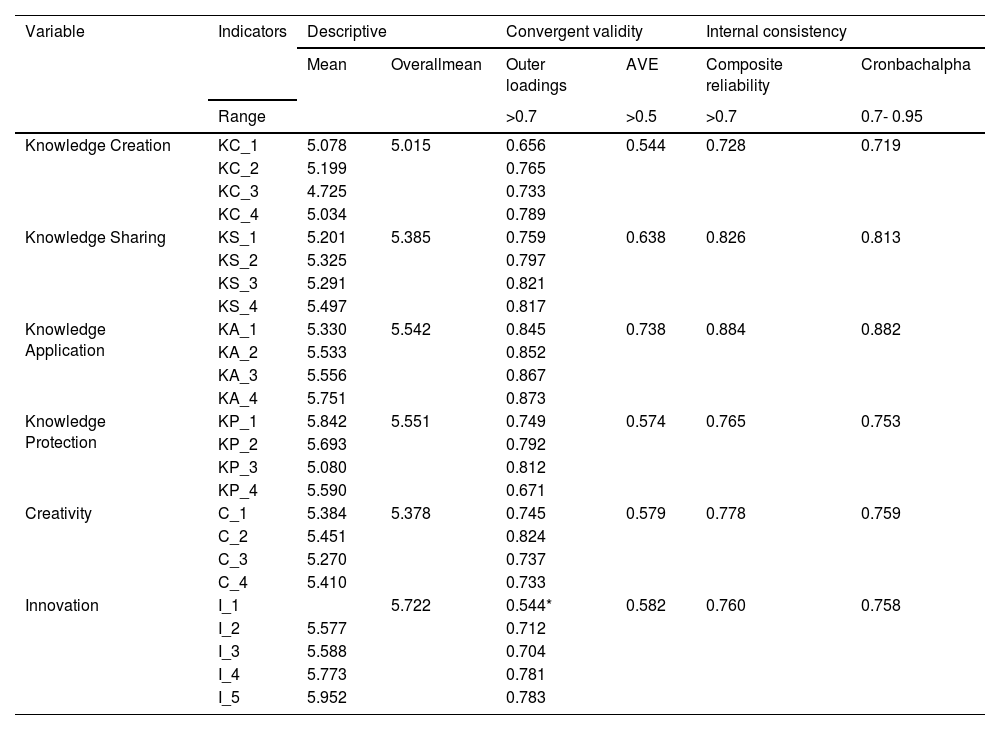

As illustrated in Table 1, potentially troublesome measures with low item loadings below the 0.7 threshold are identified by the loading estimate (Hair et al., 2020), such as KC_1 (0.649), KP_4 (0.669), and I_1 (0.544). Because the item loadings of (KC_1) and (KP_4) are closer to 0.7, they were considered for the analysis (Saunders et al., 2009). However, item (I_1) was removed from further analysis. The values for Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability are found between 0.7 and 0.95, indicating the internal consistency of the items being used. The AVE also falls between the ranges of 0.5 and 1, ensuring the convergent validity of the model.

Item loading, cross loading, convergent validity.

| Variable | Indicators | Descriptive | Convergent validity | Internal consistency | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Overallmean | Outer loadings | AVE | Composite reliability | Cronbachalpha | ||

| Range | >0.7 | >0.5 | >0.7 | 0.7- 0.95 | |||

| Knowledge Creation | KC_1 | 5.078 | 5.015 | 0.656 | 0.544 | 0.728 | 0.719 |

| KC_2 | 5.199 | 0.765 | |||||

| KC_3 | 4.725 | 0.733 | |||||

| KC_4 | 5.034 | 0.789 | |||||

| Knowledge Sharing | KS_1 | 5.201 | 5.385 | 0.759 | 0.638 | 0.826 | 0.813 |

| KS_2 | 5.325 | 0.797 | |||||

| KS_3 | 5.291 | 0.821 | |||||

| KS_4 | 5.497 | 0.817 | |||||

| Knowledge Application | KA_1 | 5.330 | 5.542 | 0.845 | 0.738 | 0.884 | 0.882 |

| KA_2 | 5.533 | 0.852 | |||||

| KA_3 | 5.556 | 0.867 | |||||

| KA_4 | 5.751 | 0.873 | |||||

| Knowledge Protection | KP_1 | 5.842 | 5.551 | 0.749 | 0.574 | 0.765 | 0.753 |

| KP_2 | 5.693 | 0.792 | |||||

| KP_3 | 5.080 | 0.812 | |||||

| KP_4 | 5.590 | 0.671 | |||||

| Creativity | C_1 | 5.384 | 5.378 | 0.745 | 0.579 | 0.778 | 0.759 |

| C_2 | 5.451 | 0.824 | |||||

| C_3 | 5.270 | 0.737 | |||||

| C_4 | 5.410 | 0.733 | |||||

| Innovation | I_1 | 5.722 | 0.544* | 0.582 | 0.760 | 0.758 | |

| I_2 | 5.577 | 0.712 | |||||

| I_3 | 5.588 | 0.704 | |||||

| I_4 | 5.773 | 0.781 | |||||

| I_5 | 5.952 | 0.783 | |||||

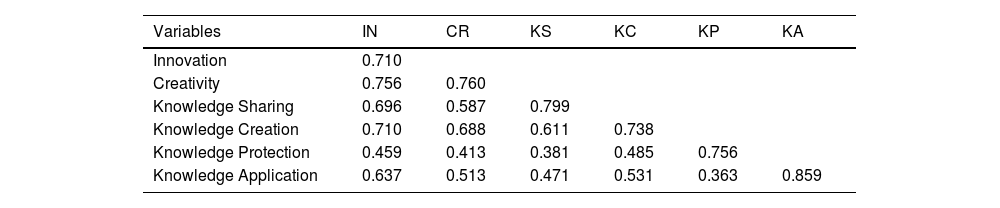

The study ensured discriminant validity through the Fornell-Larcker test, as illustrated in Table 2, and item cross-loadings in Annexure 02. These variables ensure discriminant validity when the shared variance with the construct exceeds the shared variance between constructs (Hair et al., 2020). According to the Forner-Larcker test, the square root of the construct's AVE (shared variance with construct) was greater than its highest correlation with any other construct. This ensured discriminant validity of the dataset. Additionally, as indicated in Annexure 02, the outer loadings of the indicator are higher than its cross-loadings with the other constructs, except C_2. We further examined the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) to evaluate collinearity issues. A model encounters a collinearity issue when the VIF value exceeds 5 (Hair et al., 2020). According to the data, the VIF value ranges from 1.00 - 3.18, which illustrates that there are no multicollinearity issues in the data set.

Fornell larcker criterion.

| Variables | IN | CR | KS | KC | KP | KA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation | 0.710 | |||||

| Creativity | 0.756 | 0.760 | ||||

| Knowledge Sharing | 0.696 | 0.587 | 0.799 | |||

| Knowledge Creation | 0.710 | 0.688 | 0.611 | 0.738 | ||

| Knowledge Protection | 0.459 | 0.413 | 0.381 | 0.485 | 0.756 | |

| Knowledge Application | 0.637 | 0.513 | 0.471 | 0.531 | 0.363 | 0.859 |

IN: Innovation, CR: Creativity, KS: Knowledge Sharing, KC: Knowledge Creation, KP: Knowledge Protection, KA: Knowledge Application

When attention is paid to the descriptive statistics presented in Table 1, the overall mean values of all the considered variables represent values above the ‘agree’ level of the seven-point scale. This implies that KC, KS, KA, KP, innovation, and employee creativity are above average in the Sri Lankan banking industry.

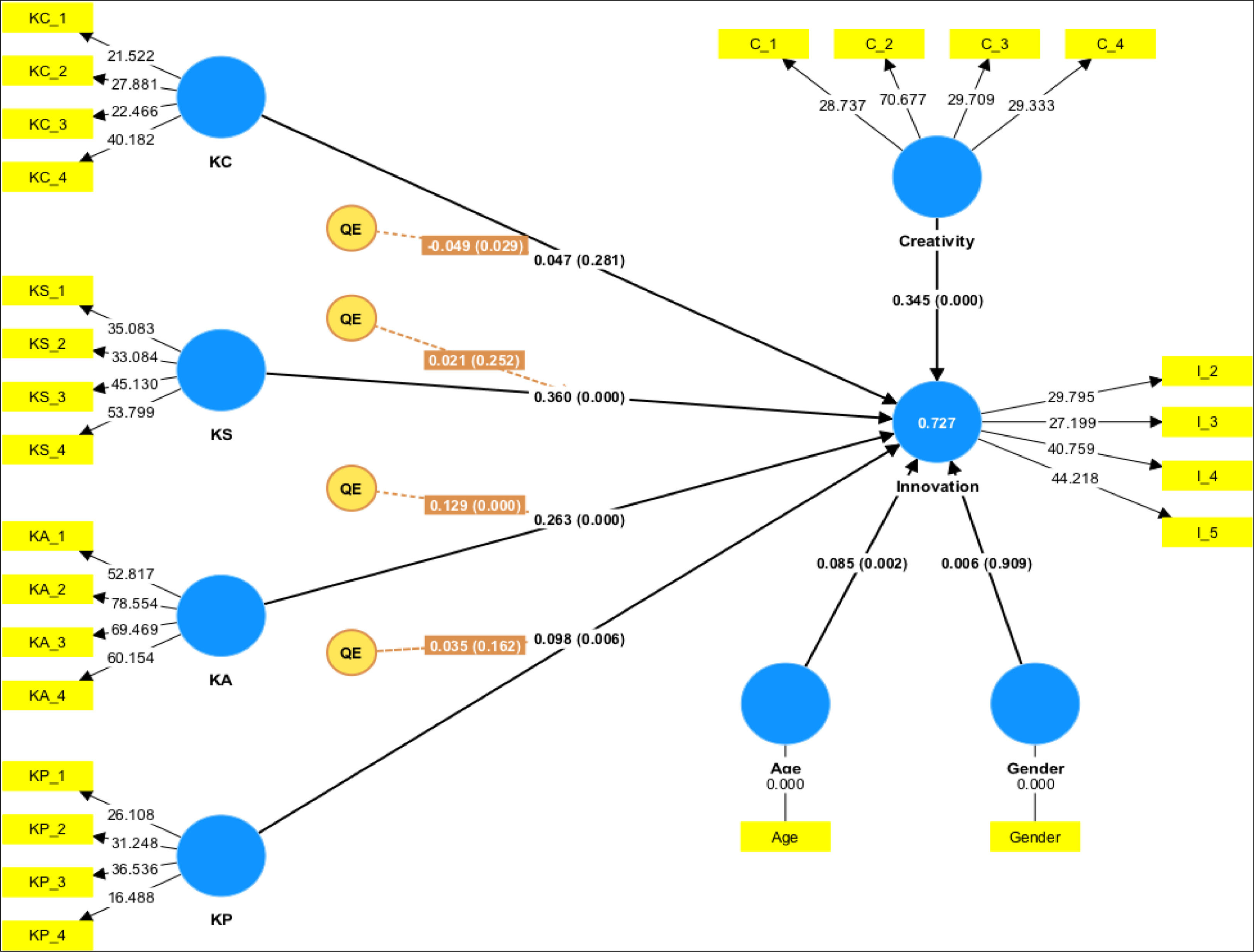

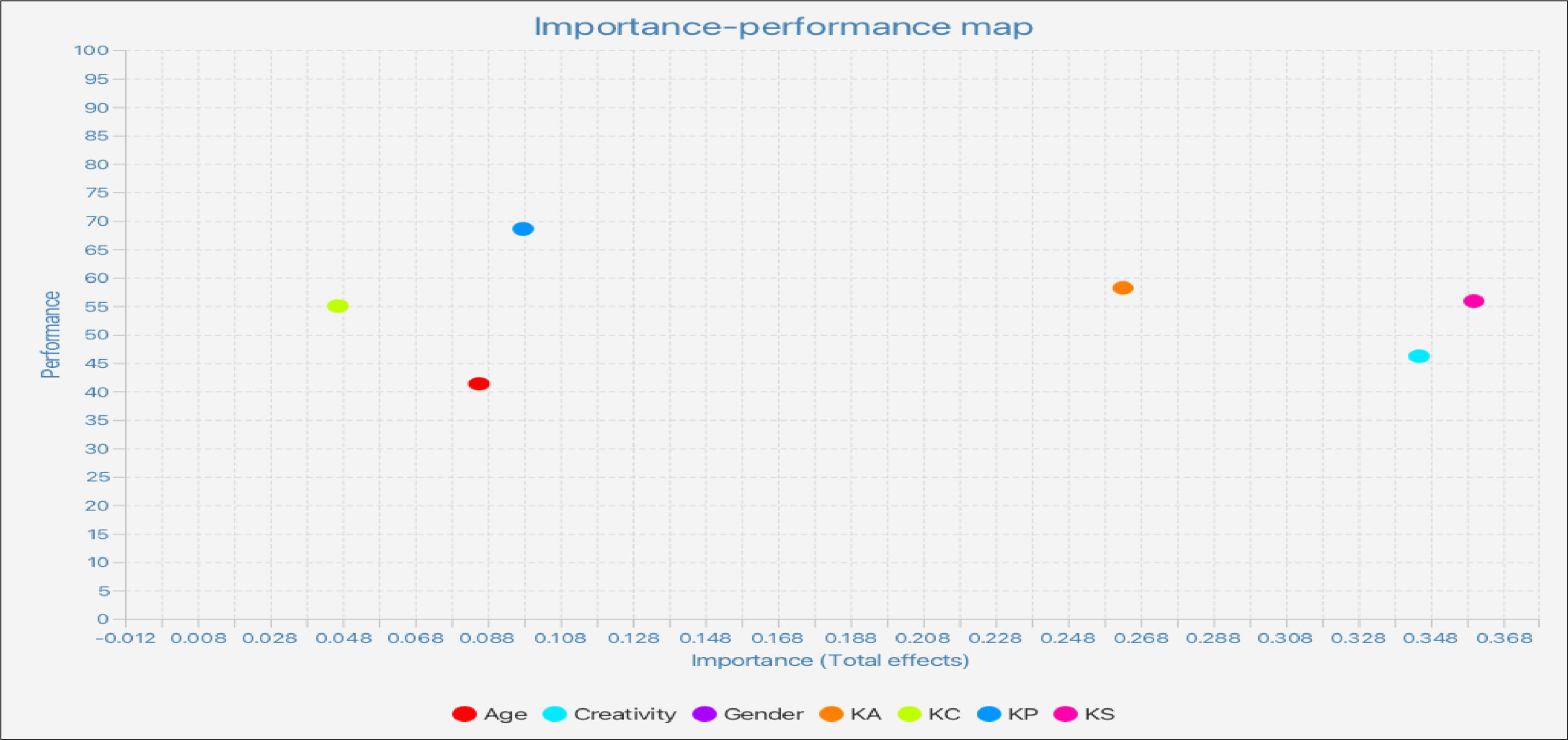

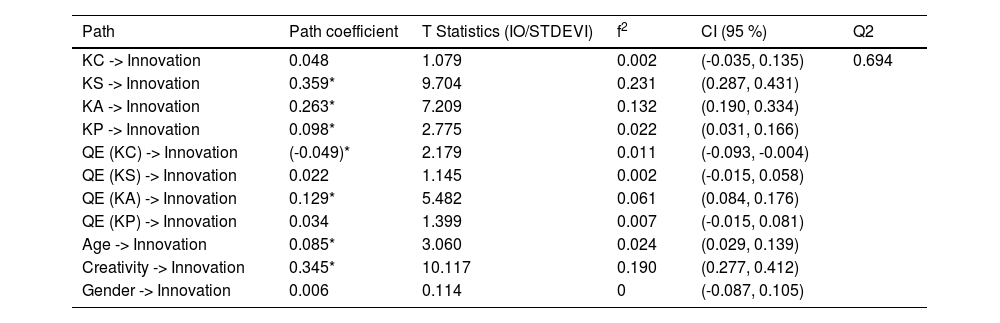

Structural model: stage twoThe structural model uses a bootstrap resampling approach with 5000 subsamples (Joseph F. Hair et al., 2016), and the output of the SEM analysis is illustrated in Fig. 2 and Table 3. The model fit statistics indicated that SRMR = 0.087, d_ULS = 2.646, d_G = 1.049, chi-square = 2404.793, and NFI = 0.618. As illustrated by Hair et al. (2020), this study first confirms the absence of multicollinearity among higher-order constructs through the VIF value, which ranges below five. Second, the predictive capability of the structural model was assessed using the coefficient of determination (R2), effect size (f2), and blindfolding (Q2). As the table indicates, the model's R2 was 72.7 %, indicating that 72.7 % of the variation in firm innovation was explained by the variables considered in the model. Effect size illustrates the predictive power of each independent variable. When f2 > 0.35, the effect is high; 0.35 > f2 > 0.15, the effect is medium, and the effect becomes low if f2 <0.02 (Hair et al., 2020). As shown in the table, KS (f2 = 0.231), innovation (f2 = 0.190), and KA (f2 = 0.132) showed the highest effect sizes on firm innovation processes. The effect of these variables compared to the rest is graphically visible through the Importance Performance Map (IPM) shown in Fig. 3. The predictive relevance of the model is (Q2 = 0.694). When the value is above zero, the model establishes predictive relevance.

Output of structural equation modelling.

| Path | Path coefficient | T Statistics (IO/STDEVI) | f2 | CI (95 %) | Q2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KC -> Innovation | 0.048 | 1.079 | 0.002 | (-0.035, 0.135) | 0.694 |

| KS -> Innovation | 0.359* | 9.704 | 0.231 | (0.287, 0.431) | |

| KA -> Innovation | 0.263* | 7.209 | 0.132 | (0.190, 0.334) | |

| KP -> Innovation | 0.098* | 2.775 | 0.022 | (0.031, 0.166) | |

| QE (KC) -> Innovation | (-0.049)* | 2.179 | 0.011 | (-0.093, -0.004) | |

| QE (KS) -> Innovation | 0.022 | 1.145 | 0.002 | (-0.015, 0.058) | |

| QE (KA) -> Innovation | 0.129* | 5.482 | 0.061 | (0.084, 0.176) | |

| QE (KP) -> Innovation | 0.034 | 1.399 | 0.007 | (-0.015, 0.081) | |

| Age -> Innovation | 0.085* | 3.060 | 0.024 | (0.029, 0.139) | |

| Creativity -> Innovation | 0.345* | 10.117 | 0.190 | (0.277, 0.412) | |

| Gender -> Innovation | 0.006 | 0.114 | 0 | (-0.087, 0.105) |

SRMR = 0.087, d_ULS = 2.646, d_G = 1.049, Chi-square = 2404.793, NFI = 0.618.

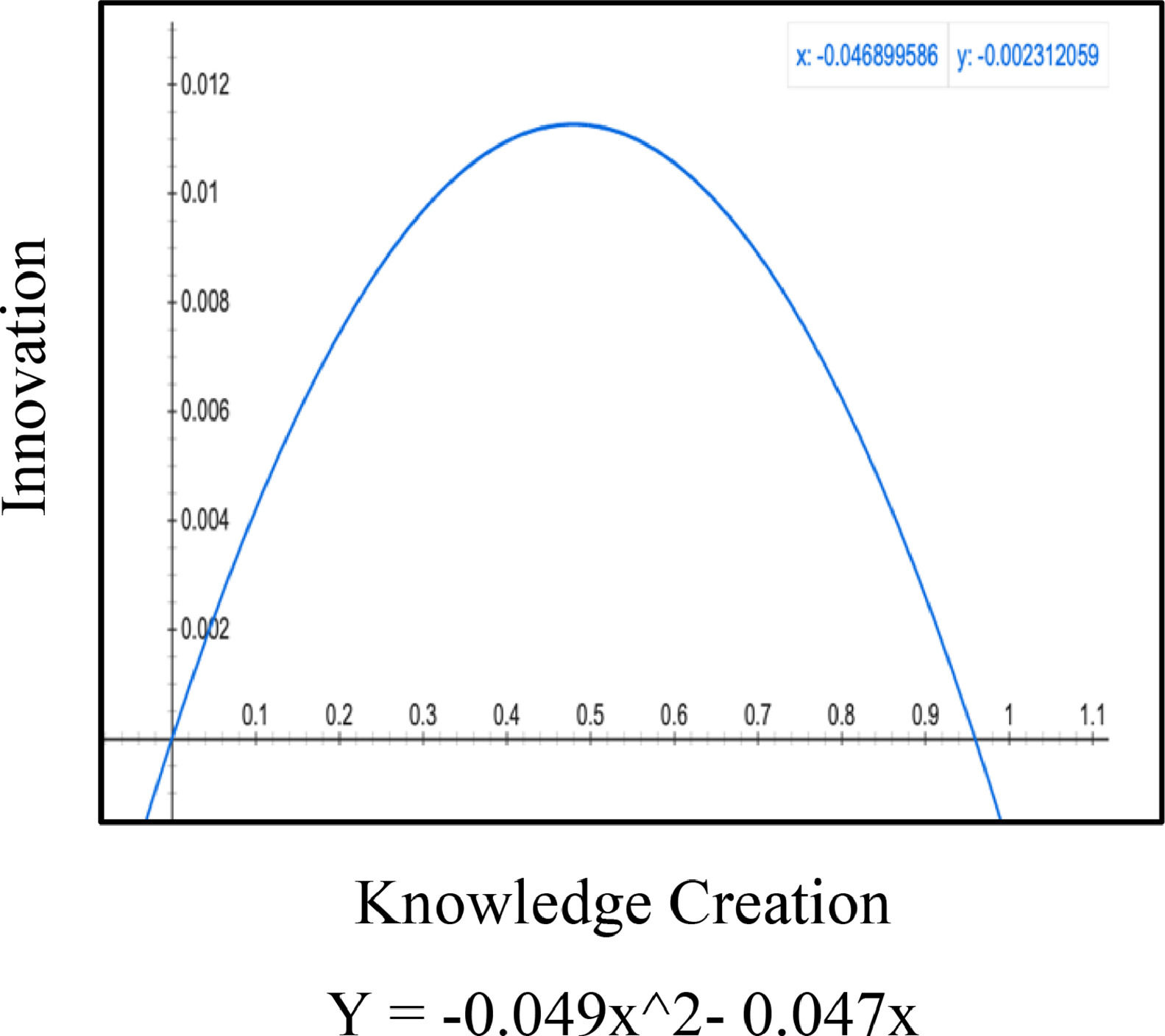

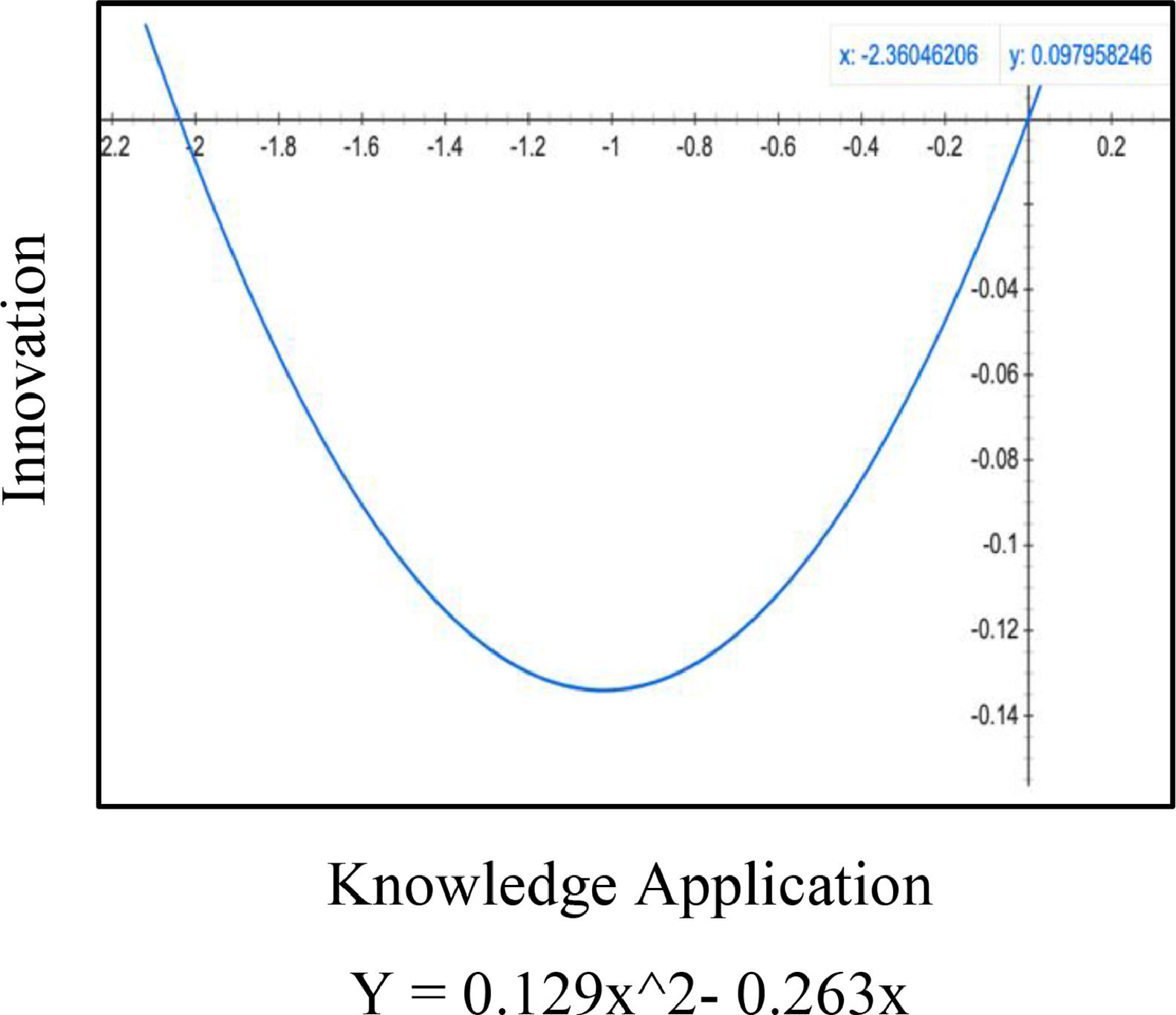

The output of the structural model is used to evaluate the developed hypotheses. As per the table, the effect of QE KC [β = -0.049, t = 2.179, (-0.093 -0.004), p < 0.05] and QE KA [β = 0.129, t = 5.482, (0.084 -0.176), p < 0.05] on firm innovation is non-linear and statistically significant. As a result, this study confirms H1 and H3. The relationship between KC and firm innovation is an inverted U-shape, whereas that between KA and firm innovation is a U-shape. According to the quadratic function (Fig. 4), firm innovation increases in line with KC up to a certain level, after which it begins to decline as KC continues. However, as shown in Fig. 5, the level of innovation decreases when a firm starts to apply knowledge; however, after a certain point, KA encourages the innovation process.

The relationships KS [β = 0.359, t = 9,704, (0.287, 0.431), p < 0.05], and KP [β = 0.098, t = 2,775, (0.031, 0.166), p < 0.05] are statistically significant, and linear with firm innovation, conforming to H2 and H4. The model controls for the effect of employee creativity, age, and gender. The effects of creativity [β = 0.345, t = 10.117, (0.277, 0.412), p < 0.05] and age [β = 0.085, t = 3.060, (0.029, 0.139), p < 0.05] are statistically significant, whereas gender [β = 0.006, t = 0.114, (-0.087, 0.105), p > 0.05] is insignificant.

Discussion of the resultThis study explores the nature of the relationship between KM and firm innovation through four hypotheses, finding that KM has both a linear and a non-linear relationship with firm innovation.

The hypothesis (H1) assumes that KC has a significant linear or non-linear relationship with firm innovation. Descriptive statistics presented in Table 1 indicate that KC, in the Sri Lankan banking sector, is at an ‘agreed’ level (5.015) on a seven-point scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Extensive employee encouragement to follow professional and academic programs (5.199), new research knowledge (5.034), various training programs (5.078), and networking with other entities (4.725) were the main reasons for a higher level of KC. Thus, KC creation is an active and ongoing endeavour in the Sri Lankan banking industry. As per the statistics presented in Table 3, the linear effect of KC on firm innovation is not statistically significant (p = 0.281). However, detailed analysis noticed that this effect is non-linear (p = 0.029) inverted ‘U’-shaped (Fig. 4). Accordingly, this study confirms H1: Knowledge creation has a significant non-linear relationship with firm innovation. The outcomes of this study are consistent with those of many previous studies. Ahuja (2002) explains that knowledge creation can have explicit non-linear relationships, especially with the types of innovation. At inception, the creation of new knowledge drives more radical innovation within the firm; however, the accumulation of such knowledge leads to accelerated incremental innovation, which later shows a diminishing return with radical innovation. Li et al. (2018) state that the effectiveness of KC declines when knowledge is inadequately internalised. Knowledge internalisation is subject to individual experience, knowledge acquisition, and internal communication (Li et al., 2018). Most of our samples were aged between 26 and 35 years, which means that they have a relatively low level of experience, leading to a higher likelihood that knowledge internalisation is at a low level. Moreover, excessive sharing of knowledge (McLeod et al., 2022; Sáenz et al., 2009), and falling knowledge into the wrong hands (Ritala et al., 2018) diminish the value of KC; thus, continuous innovation under persistent KC is not possible.

Hypothesis (H2) suggests that KS has a significant linear or non-linear relationship with firm innovation. As per the statistics (Table 1), the coefficient of the linear relationship is 0.326, and its level of significance is (p = 0.000); thus, the relationship becomes linear and statistically significant. As shown in the table, the non-linear effect of KS was not statistically significant (p = 0.252). This study confirms the linear relationship between KS and firm innovation in the Sri Lankan banking sector. This finding is consistent with those of several previous studies (Arsawan et al., 2022; McLeod et al., 2022; Sáenz et al., 2009). Arsawan et al. (2022) state that SMEs succeed in competitive markets by fostering knowledge-sharing practices as KS promotes an innovative culture within SMEs. According to statistics, knowledge sharing has become a norm in Sri Lankan banks (5.497), mainly because experienced employees share their know-how with younger employees (5.325), banks organise cross-departmental training and workshops (5.201), and reward KS practices (3.291), which together promote innovations within the banks. Allameh (2018) asserted that KS influences firm innovation through human, structural, and relational capital. Banks establish relational capital through cross-departmental training and KS sessions. In the hospitality industry, the exchange of knowledge between hotel managers and owners facilitates innovation (McLeod et al., 2022). These studies align with the statement that KS has a linear relationship with firm innovation, as emphasised in the present study.

Hypothesis (H3) states that KA has a significant linear or non-linear relationship with firm innovation. According to the descriptive statistics, KA is at a higher level in Sri Lankan banks (5.385). continuous updates of working processes (5.751), utilisation of internal and external knowledge in product/service development (5.533), and application of previous learning (5. 330) was the cause of this high level of KA. Examination of the relationship between KA and firm innovation reveals that KA has statistically significant linear (0.263, p = 0.000) and non-linear (0.129, p = 0.000) relationships with firm innovation. Accordingly, the results of this study confirm this hypothesis. The detailed attention to the non-linear relationship found that it is “U” shape (Fig. 5), indicating that innovation performance declines initially with KA, and it starts to increase after a certain time. The U-shaped relationship can occur due to the resource constraint of the organisation (Chen & Shen, 2023) as new knowledge requires different resources to practice it effectively, and resource-constrained firms in such situations struggle to boost innovation by new KA. In addition, the adaptation of the firm towards a new KA significantly influences lower initial innovation outcomes. This adaptation, as explained by Eisenhardt and Martin (2000), is the dynamic capabilities of a firm, in which firms that are more dynamic to external changes quickly adapt to new knowledge and innovate compared to other firms. KA involves significant risks and often employs trial-and-error methods, leading to unexpected results at the onset of innovation (Allen, 2013). Linear and non-linear relationships between KA and firm innovation are possible when different types of innovation are considered. For example, radical innovation follows a non-linear pattern in an organisation, while incremental innovation maintains a linear relationship with KA (Ritala et al., 2018; Zhou & Li, 2012). Firms with various strategic units that follow different strategic directions, such as exploitation and exploration, can also result in different innovation patterns, even within the same firm (Gupta et al., 2006; Ritala et al., 2022).

Hypothesis (H4) assumes that KP has a significant linear or non-linear relationship with firm innovation. As per the statistics presented in Table 3, the coefficient of the linear relationship between KP and firm innovation is (0.098, P = 0.006), indicating that KP has a statistically significant linear relationship with firm innovation in Sri Lankan banks. However, this non-linear relationship was statistically significant (0.035, P = 0.162). Our findings align with those of previous studies, such as Ode and Ayavoo (2020); Olander et al. (2014), who highlight the importance of safeguarding knowledge to expedite firm innovation. Olander et al. (2014) stated that KP fosters innovation, particularly when information is limited. For radical innovation, the protection of knowledge is more beneficial, as the excessive diffusion of knowledge diminishes its intrinsic value (Li et al., 2008). Sri Lankan banks made substantial efforts (5.551) to protect their knowledge of future applications. These efforts include knowledge documentation (5.842), technology applications (5.693), special care for competitive knowledge (5.080), and codifying employee experience (5.590). Ritala et al. (2022) assert that organisations need to strike a balance between KP and KS, as the extremes of either can be detrimental to an organisation's health. Therefore, we advise safeguarding the ‘core knowledge’ for future application through special mechanisms. All of these factors have contributed to the present significant relationship between KP and firm innovation.

Overall, KC, KS, KA, and KP have different effects on bank innovation. Drawing on the recent study of Al‐Muayad and Chen (2024), this study claims that KM dimensions ultimately impact bank performance in Sri Lanka through their varying contributions to innovation. Since KM is critical for any organisation (Al‐Muayad & Chen, 2024), the Sri Lankan banking sector can focus on KC activities such as training, research, and networking to foster new knowledge creation for innovation. Knowledge sharing can be facilitated through both formal and informal mechanisms, including training sessions and personal discussions. Bank performance can be enhanced by applying this knowledge to drive innovation. Protecting such knowledge minimises errors during innovation. Given the incremental nature of innovation, KP can form the foundation of new knowledge creation, thereby illustrating the spiral effect of KM.

Implication and concluding remarksThe relationship between KM and firm innovation, especially in the banking and finance industries, remains unclear in the existing literature. This study aims to minimise this gap by considering the Sri Lankan banking sector. This study considers 437 usable responses from banking employees and tests four hypotheses using smart PLS. The findings illustrate that the four KM dimensions contribute differently to firm innovation through linear and non-linear relationships.

This study makes significant contributions to theory and practice in several ways. Theoretically, this study contributes to the existing literature by explaining how each dimension of KM displays different behavioural patterns (linear and non-linear) on firm innovation within an integrated framework. Most previous studies have explored either one dimension or a linear relationship in their framework; such an application limits its scope to explaining the dynamism between the different dimensions of KM. In practice, all four KM dimensions are applied simultaneously. Therefore, understanding the internal dynamics of these dimensions is timely and important. Our investigation addresses this gap in literature. In addition, our data come from an emerging developing country context where knowledge management practices are still operating at their infant stage compared to developed Westernised economies; consequently, our study findings will be more beneficial to them to understand the dynamic behaviour of KM on firms’ innovation, advancing the existing stock of knowledge in the context of emerging developing countries.

This study reveals the potential disadvantages of KC and KA in the innovation process from a managerial perspective. Since the relationship between KC and firm innovation is not strictly linear, excessive KC can be detrimental to an organisation, particularly when a firm engages in radical innovation and when the systematic sharing and protection of knowledge are not under managerial control. As Ahuja (2002); Li et al. (2008), the diffusion of knowledge minimises radical innovation capability and the intrinsic value of knowledge. Additionally, the behaviours of KC and KA in relation to innovation tend to change after a certain period. Therefore, the challenge lies in understanding the threshold and taking action to start a new loop of KC and KA, while controlling diminishing returns. Hence, management should remain vigilant about the behaviour of KC and KA in the innovation process. Furthermore, as per our results, we emphasise that the organisation can leverage the maximum benefit if management is more concerned with linear relationships (KS and KP). However, the literature advises that management should balance KS and KP (Ritala et al., 2022) in resource allocation because extremes in KS and KP can reduce innovation performance. Finally, it is crucial to emphasise that managers need to exercise caution in understanding the behaviour of each KM function before making managerial decisions to promote these functions as they do not equally contribute to the innovation process.

Limitations and future research areasThis study has several limitations. First, because this research was conducted in the banking and finance industry in Sri Lanka, the generalisability of the research findings is limited. Consequently, different results may be obtained in different industries and countries. Therefore, other industries should use their output cautiously. To address this limitation, future studies should focus on comparing how these dimensions behave differently within an integrated framework, especially in the context of emerging and developed countries. Second, as KC and KA have non-linear relationships with innovation, future studies should consider the point at which these two variables start to decrease innovation performance. Third, it is noteworthy to focus on future studies exploring the non-linear relationships of KM dimensions between different innovations, such as radical vs. incremental and product vs. service innovation. This study identifies relatively limited literature on KA and KP; therefore, we believe that future studies have more opportunities to explore KA, for example, at the individual, group, and firm levels, and the protection of non-patent knowledge within the organisation.

CRediT authorship contribution statementHarshani Dedunu: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. Salinda Weerasinghe: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Software, Methodology, Conceptualization. Ananda Wickcramasinghe: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

This study has not been supported financially by any project or grant.

| No | Bank | Number of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 01 | Bank of Ceylon (BOC) | 8479 |

| 02 | Peoples Bank | 7692 |

| 03 | National Saving Bank (NSB) | 4641 |

| 04 | Sampath Bank | 4048 |

| 05 | Commercial Bank | 5072 |

| 06 | Hatton National Bank (HNB) | 4836 |

| 07 | Seylan Bank | 3148 |

| 08 | Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC) | 1700 |

| 09 | National Development Bank | 2169 |

| 10 | Pan Asia Banking Corporation PLC | 1629 |

| Total | 43414 |

Source: Internet-based information as of 10th August 2022.

| Variables | Knowledge creation | Knowledge sharing | Knowledge application | Knowledge protection | Creativity | Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KC_1 | 0.649 | |||||

| KC_2 | 0.771 | |||||

| KC_3 | 0.734 | |||||

| KC_4 | 0.791 | |||||

| KS_1 | 0.759 | |||||

| KS_2 | 0.797 | |||||

| KS_3 | 0.821 | |||||

| KS_4 | 0.818 | |||||

| KA_1 | 0.845 | |||||

| KA_2 | 0.852 | |||||

| KA_3 | 0.866 | |||||

| KA_4 | 0.873 | |||||

| KP_1 | 0.730 | |||||

| KP_2 | 0.812 | |||||

| KP_3 | 0.804 | |||||

| KP_4 | 0.669 | |||||

| I_1 | 0.544** | |||||

| I_2 | 0.708 | |||||

| I_3 | 0.706 | |||||

| I_4 | 0.785 | |||||

| I_5 | 0.784 | |||||

| C_1 | 0.738 | |||||

| C_2 | 0.822 | 0.728* | ||||

| C_3 | 0.741 | |||||

| C_4 | 0.738 |

*the item is more relevant to measure creativity but the same item can be best used for measuring innovation too. As the Item loading exceeds its cross-loading, the item is kept as it is.

⁎⁎Removed from the analysis.

| Variables | Items | |

|---|---|---|

| Innovation | I_1I_2I_3I_4I_5 | My organisation encourages me to develop my ideas.My organisation helps me to “talk up” new ways of doing things.My organisation likes me to try new ways of doing my job.My organisation is the first to launch new products/services compared to competitors.My organisation takes the lead in using new technologies compared to competitors. |

| Knowledge Creation | KC_1KC_2KC_3KC_4 | My organisation organizes several training programmes to update employees with new knowledge.My organisation encourages employees to follow academic and professional programmes to acquire new and current knowledge.My organisation encourages employees to network with different entities for knowledge creation.My organisation encourages employee research for new knowledge. |

| Knowledge Sharing | KS_1KS_2KS_3KS_4 | In my organisation, cross-department training programs/workshops/seminars are organized to share knowledge among employees.In my organisation experienced employees often share their knowledge with staff members.My organization rewards knowledge sharing among others.Knowledge sharing among colleagues is considered normal in my organization. |

| Knowledge Application | KA_1KA_2KA_3KA_4 | My organisation applies lessons learned from previous experiences to a current problem.My organisation requests us to apply our knowledge/experience/ customers’ feedback to design or improve new products, services, and processes.My organisation encourages us to apply previous successful knowledge application to mitigate similar problems in the future.My organisation updates standard operating procedures/work manuals from time, to time considering previous learning. |

| Knowledge Protection | KP_1KP_2KP_3KP_4 | My organisation documents knowledge for future applications.My organisation uses computer applications to safeguard knowledge, such as ERP, SAP, or any special systems.My organisation has special mechanisms to protect competitive knowledge.Employees are encouraged to codify their know-how about their current job. |

| Creativity | C_1C_2C_3C_4 | I always look at problems with a fresh view.I do my best to come up with creative solutions to problems.I feel free to apply my creative ideas in my office.I have intrinsic motivation to propose novel ideas for the problem. |