Persisting global crises, such as COVID-19, pose significant challenges for international companies. The increase in uncertainty and instability in foreign markets has profoundly affected firms' strategic decisions, forcing them to adapt to dynamic conditions in order to maintain or improve their international performance. Grounded in the dynamic capabilities view, this study examines how exploration and exploitation strategies drive international business model innovation, ultimately affecting international performance and expectations concerning crisis survival during the COVID-19 crisis.

Utilizing survey data from 1455 internationalized companies, we use structural equation modeling to test our hypotheses. The results show that, although both exploration and exploitation strategies foster international business model innovation, exploration has a stronger effect than exploitation. The results further emphasize that international business model innovation has a positive impact not only on the expectation of crisis survival but also on the international performance.

International business has always involved a degree of risk and uncertainty, forcing firms previously confined to domestic markets to explore opportunities in foreign markets (Sharma et al., 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic exerted a profound impact on the global economy and international trade, leading to a substantial deceleration or near cessation of most international business activities in certain moments. This pandemic can be characterised as an environmental shock, defined as a set of ``transient perturbations whose occurrences are difficult to foresee and whose impacts on organizations are disruptive and potentially inimical'' (Meyer, 1982, p. 515). A direct consequence of such shocks is an increased level of environmental dynamism, which refers to the unpredictability and uncertainty arising from the intensity and frequency of changes in the external environment (Miller & Friesen, 1983).

The radical uncertainty and unpredictability during the COVID-19 pandemic posed significant challenges to international firms (Attah-Boakye et al., 2023; Ciszewska-Mlinarič et al., 2024; Sharma et al., 2020). These challenges inevitably forced companies to rethink their strategic decisions and adapt their products, processes, services, and business models to the new conditions in order to ensure their survival and maintain their competitiveness in foreign markets (Ahn et al., 2018; Colovic, 2022; Evers et al., 2023; Radziwon et al., 2022). This study examines two different adaptation strategies that firms can employ in response to the COVID-19 global crisis: exploitation and exploration (Chou et al., 2024; Gupta et al., 2006; March, 1991; O'Reilly & Tushman, 2013; Osiyevskyy et al., 2020). In his seminal work, March (1991, p. 71) defines exploration as encompassing “search, variation, risk-taking, experimentation, play, flexibility, discovery and innovation'', which enables firms to adapt and adopt new knowledge. In contrast, exploitation refers to “refinement, choice, production, efficiency, selection, implementation and execution”, which allows firms to improve operational efficiency.

The international business literature has progressively adopted exploitation and exploration strategies as analytical frameworks to analyse several outcomes (Asemokha et al., 2019; Ju & Gao, 2022; Liu et al., 2022; Sosna et al., 2010; Sousa et al., 2020), such as international performance (Asemokha et al., 2019) and the evolution of business model innovation (BMI) (Sosna et al., 2010). Even so, recent research highlights the need for further investigation to clarify in greater detail the role of these strategies in the international business context (Liu et al., 2022; Ruano-Arcos et al., 2024). Furthermore, the adoption of exploitation and exploration strategies has been recognised as particularly advantageous for firms operating in turbulent and uncertain environments (Chou et al., 2024; O'Reilly &Tushman, 2013).

The rapid response required by the COVID-19 pandemic necessitates novel approaches to organisational ambidexterity—that is, the simultaneous pursuit of both strategies (Radziwon et al., 2022). However, the effectiveness of exploitation and exploration strategies in the face of radical uncertainty, such as the one induced by the COVID-19 global crisis, remains poorly understood (Chou et al., 2024). This study aims to address these gaps by analysing the exploitation and exploration strategies adopted by international companies in response to the COVID-19 crisis.

Given the persistent market uncertainties faced by international firms, it is crucial for them to continuously implement changes, reinvent their business processes, and seek growth opportunities to maintain profitability (Amit & Zott, 2012). The radical changes brought about by the COVID-19 crisis have profoundly affected foreign market conditions and international performance (Attah-Boakye et al., 2023; Christofi et al., 2024; Olarewaju & Ajeyalemi, 2023). This has created an urgent need for international firms to innovate their approaches and find innovative ways to create and deliver value in foreign markets (Evers et al., 2023; Lew et al., 2023; Sousa et al., 2020). Previous research suggests that BMI enables firms to identify environmental threats and opportunities, enhance organizational resilience, and improve crisis management (Salamzadeh et al., 2023), thus serving as a critical mechanism for responding effectively to global crises, such as COVID-19 (Christofi et al., 2024). Furthermore, international BMI is recognized as a key driver of international performance (Asemokha et al., 2019). Radziwon et al. (2022) argue that the urgency created by the COVID-19 pandemic requires new approaches to BMI. As a result, the role of BMI in international business has become increasingly prominent. Therefore, international BMI represents a viable solution for international firms to effectively respond to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 crisis (Attah-Boakye et al., 2023; Christofi et al., 2024).

Nevertheless, the engagement of international firms in international BMI requires that these international firms use their dynamic capabilities to renew themselves (Teece, 2014, 1997). They sense the first signs of the crisis, seize new opportunities that arise during this difficult period, and reconfigure or reorganize existing resources and capabilities to overcome the crisis and improve performance (Ballesteros et al., 2017; Crespo et al., 2023). While the determinants of firm behavior during crises and periods of decline are well documented (e.g., Trahms et al., 2013), how firms, particularly international firms, have coped with major crises, such as COVID-19, remains underexplored (Attah-Boakye et al., 2023; Christofi et al., 2024; Evers et al., 2023; Lew et al., 2023). More specifically, although there are several studies analysing the impact of BMI on firm performance (White et al., 2022) and, in particular, on international performance in uncertain environments (Evers et al., 2023; Lew et al., 2023), it is not clear how international BMI relates to international performance under the extreme uncertainty of the COVID-19 global crisis (Christofi et al., 2024). Furthermore, the BMI literature recognises that the underlying factors that truly drive BMI remain largely unexplored (Bashir et al., 2020).

To address these gaps, we propose the following research questions:

RQ1: How do exploration and exploitation strategies relate to international BMI during the COVID-19 global crisis? What are the differences in the impact of exploration and exploitation strategies on innovation of the international business model?

RQ2: How does international BMI impact performance (international performance and expectations concerning crisis survival) during the COVID-19 global crisis?

This study builds on the dynamic capability view (hereafter DCV) (Teece, 2014) to address these research questions. We hypothesise that the adoption of exploitation and exploration strategies positively affects international BMI, and that this effect is stronger for the exploration strategy. In addition, we hypothesise a positive effect of international BMI on both international performance and expectations concerning crisis survival. Using survey data from 1455 internationalized firms and covariance-based structural equation modelling (CB-SEM), we test the proposed hypotheses.

Our results show that, in the context of the COVID-19 global crisis, the adoption of both exploration and exploitation strategies positively influences international BMI, with exploration having a stronger impact. Furthermore, the results indicate that international BMI during the COVID-19 crisis positively influences both international performance and expectations concerning crisis survival.

From our results, we make four important contributions to the international business literature, which are of practical relevance because firms need to know how to deal with high levels of uncertainty, such as those created by the COVID-19 global crisis. First, our study provides a better understanding of the role of exploitation and exploration strategies in complex environments. Second, we add new insights into the drivers of international BMI in the context of a global crisis, an issue that remains unclear (Christofi et al., 2024). More specifically, we clarify how exploitation and exploration strategies lead international firms to engage in BMI as a response to global crisis. Third, we contribute to the knowledge of the outcomes associated with BMI—namely, international performance and expectations concerning crisis survival, in a global crisis context. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the existing relationship between international BMI and both international performance and expectations concerning crisis survival in an international context. Fourth, this study is based on a sample that includes firms of different sizes and not only SMEs as considered in the existing literature. In sum, our study emphasizes the critical role of exploitation and exploration strategies in driving international BMI so that international companies can successfully respond to a severe global economic crisis.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. The next section presents a comprehensive review of the relevant literature and, in the section that follows, a presentation of the conceptual model and research hypotheses. The methodological decisions are outlined in the fourth section. Then, the data analysis and results are presented followed by a discussion of the results. Finally, we conclude by presenting the theoretical and managerial implications, the study's limitations, and suggestions for future research.

Literature reviewInternationalization and exploitation and exploration strategiesCrises require firms to quickly make decisions and adapt their strategic behavior to ensure firms’ viability (Beliaeva et al., 2020; Kunc & Bhandari, 2011; Martí, 2017). This is particularly true for extreme crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Osiyevskyy et al., 2020). Thus, how to survive a global crisis, such as COVID-19, is a fundamental issue for both national and international firms (Chou et al., 2024). There are several possible ways that firms can respond to a crisis (e.g., Beliaeva et al., 2020; Chou et al., 2024; al., 2014 by Trahms et al., 2013."?>Trahms et al., 2013). Among the possible ways are exploitation and exploration adaptation strategies (Almahendra & Ambos, 2015; Gupta et al., 2006; March, 1991; O'Reilly & Tushman, 2013). These strategies are particularly important when firms face an extreme economic crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Osiyevskyy et al., 2020).

Exploratory innovations are radical advances, aiming to meet the needs of new customers or markets (Benner & Tushman, 2003, p. 243). These innovations introduce novel designs, create new markets, and develop alternative distribution channels. They require the development of new knowledge and capabilities (He & Wong, 2004; Jansen et al., 2006; Levinthal & March, 1993; Osiyevskyy et al., 2020; Uotila, 2017). In contrast, exploitative innovations are incremental and tailored to meet the needs of existing customers or markets (Benner & Tushman, 2003, p. 243). Such innovations focus on the use and improvement of existing knowledge and capabilities, the refinement of established designs, the expansion of current products and services, and the optimization of existing distribution channels (He & Wong, 2004; Jansen et al., 2006; Levinthal & March, 1993; Osiyevskyy et al., 2020; Uotila, 2017). As a result, exploitative innovations build on and reinforce existing knowledge, skills, processes, and structures (Levinthal & March, 1993).

While exploitation can lead to positive short-term performance effects by reducing variety and increasing efficiency, exploration strategies focus on variance-increasing activities that allow the firm to achieve positive long-term performance effects (Uotila, 2017).

Although these strategies compete for resources and have inherent contradictions (March, 1991; Smith et al., 2010), there is a consensus in the literature that firms must balance these strategies to ensure their survival and competitive advantage (e.g., He & Wong, 2004; March, 1991; Osiyevskyy et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020). Two of the most widely studied ways to balance exploitation and exploration strategies are ambidexterity—simultaneous pursuit of both strategies (Gupta et al., 2006; He & Wong, 2004; Kassotaki, 2022)—and temporal transition meaning that strategies can separate or coexist over time (Gupta et al., 2006; Kang & Kim, 2020).

Exploitation and exploration strategies have been extensively studied in the management literature (e.g., Almahendra & Ambos, 2015; Gupta et al., 2006; He & Wong, 2004; Kang & Kim, 2020; Shi et al., 2020). There is also a large body of literature that has focused on ambidexterity (He & Wong, 2004; Jansen et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2022; Luger et al., 2018; Nyagadza, 2022). Most of these studies have examined how exploration, exploitation, and ambidexterity affect firm performance (Junni et al., 2013; Kang & Kim, 2020; Shi et al., 2020), and most of them suggest that firms should consider both strategies (He & Wong, 2004; Shi et al., 2020) because balancing exploration and exploitation leads to complementary returns (Luger et al., 2018). Even so, the literature has produced some controversial results (Shi et al., 2020). For example, some studies suggest that both exploitation and exploration should be used to achieve higher levels of performance. Conversely, other studies suggest that firms that focus on one strategy alone outperform those that combine both, while others argue that this approach is detrimental to performance (Gupta et al., 2006; Junni et al., 2013). Moreover, the existing literature has found that the effectiveness of exploitation, exploration, and ambidexterity strategies depends on specific factors (Junni et al., 2013), such as environmental aspects (e.g., Jansen et al., 2006; Luger et al., 2018), firm resources (Archibugi et al., 2013), industrial context (e.g., Chou et al., 2024), and crisis severity (Osiyevskyy et al., 2020). For example, Jansen et al. (2006) found that firms following an exploration-type strategy in a highly dynamic environment achieved better financial performance, while firms following this strategy in a stable environment reduced their financial performance.

Furthermore, the international business literature has increasingly used exploitation, exploration, and ambidexterity (Liu et al., 2022; Ruano-Arcos et al., 2024Sousa et al., 2020) to explain a variety of phenomena, such as international ambidexterity (Ruano-Arcos et al., 2024), export performance (Sharma et al., 2018), export sales growth (Sousa et al., 2020), foreign venture performance (Ju & Gao, 2022), international joint venture new product performance (Jin et al., 2016), and international performance (Osiyevskyy et al., 2020). Due to their numerous uncertainties, significant competitive pressures, and high complexity, international markets require a strong emphasis on organizational learning (Sousa et al., 2020). To cope with these changing market conditions and achieve higher performance, international firms should adopt both exploitation and exploration strategies (Ju & Gao, 2022; Sousa et al., 2020). Nevertheless, the success of exploitation, exploration, and ambidexterity strategies in international markets, as in domestic markets, is contingent on a set of internal and external factors (e.g., Ju & Gao, 2022; Sousa et al., 2020), and their impact on performance varies over time (Sousa et al., 2020). For example, Ju and Gao (2022) found that the relationship between exploration and financial performance is positively moderated by marketing capabilities, but this effect is insignificant for exploitation.

Another specific stream of the literature has been focused on the role of exploitation, exploration, and ambidexterity strategies in the context of economic crises (e.g., Archibugi et al., 2013; Beliaeva et al., 2020; Chou et al., 2024; Iborra et al., 2020), particularly the COVID-19 crisis (e.g., Clauss et al., 2022; Osiyevskyy et al., 2020; Radziwon et al., 2022). This research suggests that firms that engage in innovation are able to better cope with an economic crisis (Ahn et al., 2018; Archibugi et al., 2013; Beliaeva et al., 2020; al., 2021 by Clauss et al., 2022."?>Clauss et al., 2022; Radziwon et al., 2022), and innovation investments are concentrated in firms that were already innovative before the crisis. Moreover, the increased investments during the crisis are strongly linked to two groups—namely, great innovators and fast-growing new entrants (Archibugi et al., 2013).

Ambidexterity has been frequently proposed as a sound strategy to achieve best performance when firms deal with turbulent environments (Chou et al., 2024). However, recent studies show that, during an economic crisis, the best strategy is not always ambidexterity, and it is contingent on specific factors (e.g., Archibugi et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2024; Osiyevskyy et al., 2020). For instance, in the context of the 2008 crisis, Archibugi et al. (2013) found that firms that pursue more explorative strategies for new product and market developments have a higher likelihood of survival than those adopting either an ambidexterity strategy or an exploration strategy.

Moreover, two recent studies developed with SMEs in the context of the COVID-19 crisis found that the best strategy to achieve a high level of performance is contingent on specific factors, such as the severity of the crisis (Osiyevskyy et al., 2020) and the loss of demand or supply (Kim et al., 2024). Osiyevskyy et al. (2020) found that, when the severity of the crisis is high, exploration strategies have a positive impact on firm performance level and variability, while exploitation strategies result in a reduction in both performance level and variability. On the other hand, when the crisis severity is low, opposite results were found. In the context of SMEs, ambidexterity capabilities coupled with strategic consistency help firms to survive and recover from external events that are threatening and stressful (Iborra et al., 2020).

The concept of ambidexterity has also been used to explain how firms can compete effectively by utilising multiple business models simultaneously (Markides et al., 2013). Schneider (2019) found that firms facing high levels of exogenous change tend to focus on identifying objective opportunities, while firms operating in more stable environments focus on creating opportunities for BMI. Drawing on the literature on dynamic capabilities, organisational ambidexterity, and paradoxes, Ricciardi et al. (2016) identify the key enablers of adaptive BMI: cooperation–competition, exploration–exploitation, conformity–agency, and dynamic capabilities.

Business model innovationThe business model is a well-developed concept and is recognized as a strategic management tool for creating customer value and sustaining a firm's competitive advantage (Evers et al., 2023; Wirtz et al., 2016). The extant literature recognizes that business models (BM) are attributes of real firms that enable them to conduct business in pursuit of their organizational goals (White et al., 2022). The business model can be seen as “the direct result of strategy” (Casadesus-Masanell & Ricart, 2010, p. 212) or “the implementation of a strategy” (Wirtz et al., 2016, p. 3). It directs and translates the firm's current resources and operational capabilities into value for stakeholders, including customers, shareholders, and suppliers (Teece, 2010).

A business model can be considered an internal factor (Anzenbacher & Wagner, 2020), described as ``a practical model of technology that is ready to be copied, but also open to variation and innovation'' (Baden-Fuller & Morgan, 2010, p. 157). This definition suggests that a specific business model is akin to a recipe that emerges from practical perspectives and emphasizes the importance of tacit knowledge transfer. There are several literature reviews on business models (e.g., Budler et al., 2021; Wirtz et al., 2016; Zott et al., 2011) as well as BMI (e.g., al., 2021 by Bashir et al., 2020."?> al., 2020"?>Bashir et al., 2020; Foss & Saebi, 2017; Zhang et al., 2024). However, although a recent literature review (Zhang et al., 2024) recognizes that definitions of BM in the literature converge on the ``design or architecture of the value creation, delivery, and capture mechanisms'' of a firm (Teece, 2010, p. 172), definitions of BMI abound, and many of these definitions lack specificity (Foss & Saebi, 2017). Some studies define BMI from a partial point of view, where changes in a single component of a BM can constitute BMI, while others define BMI with the emphasis on its components.

The literature on BMI is an emerging field that builds upon the foundational concept of BM. A new business model can be viewed as a form of innovation (Teece, 2010) and does not necessarily rely on exploiting previous advantages (Ahokangas & Myllykoski, 2014), which can be beneficial compared to BMI or adaptation. In our study, we adopted the definition of BMI proposed by Casadesus-Masanell and Zhu (2013, p. 464), which defines BMI as “the search for new logics of the firm and new ways to create and capture value for its stakeholders”. This definition aligns with the three primary dimensions of a firm's business model: value creation, value proposition, and value capture (e.g., Zott et al., 2011). BMI is also referred to in the literature as ``business model adaptation'' (Landau et al., 2014) or ``business model transformation'' (Ahokangas & Myllykoski, 2014). Several scholars categorize BMI into different types. For example, Heij et al. (2014) distinguish two main forms: business model replication and business model renewal. Business model replication refers to the adoption and implementation of an already successful business model. In contrast, business model renewal involves the development of a novel and distinct business model that is different from existing ones.

The literature on BMI highlights three main outcomes. First, firm performance is a primary outcome (Bashir et al., 2021), with BMI increasingly recognized as more critical to success than product, service, and process innovation (Amit & Zott, 2012; Bashir et al., 2021; Sosna et al., 2010). A recent literature review found that the strength of this relationship decreases as the level of novelty and the frequency of BMI increase (White et al., 2022). Second, BMI often leads to competitive advantage (Bashir et al., 2021). A sufficiently differentiated business model can provide significant competitive advantage because it is difficult for other firms to imitate (Teece, 2010). In particular, intangible assets are difficult to replicate and, therefore, provide a strong competitive advantage (Lonial & Carter, 2015). The social complexity and path dependency associated with BMI also contribute to its inimitability (Bashir et al., 2021). Firms need to innovate the business model in order to achieve sustainable profitability, regardless of the resources they possess because these alone are not sufficient (Teece, 2010). Furthermore, it is more difficult for competitors to imitate an entire business model than a single product or process (Amit & Zott, 2012). Third, BMI itself is seen as a source of innovation (Bashir et al., 2021; Budler et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2024).

The BMI literature identifies several triggers, enablers, and outcomes of BMI (Bashir et al., 2021). For example, external triggers include new technologies, digitalization, and future projections, price pressure, low market coverage, customers and technology, external stakeholders, environmental factors, market pressure and technology push, market crisis or change, and financial pressure, while customer needs and feedback, and lost sales and organizational characteristics are internal triggers (Bashir et al., 2021). The main enablers recognized in the literature include organizational structure, organizational culture, organizational inertia, leadership, and technology (Bashir et al., 2021).

Innovation in business models occurs at different times and involves different experiences compared to their initial creation (Ahokangas & Myllykoski, 2014). According to Ahokangas and Myllykoski (2014, p. 14), “business model creation and innovation practices involve comprising visioning, strategizing, performing, and assessing with the goal of reaching a competitive advantage regarding a business opportunity”. Initial business models are often revised and adapted, often through a trial-and-error approach. Adjustments and the accumulation of prior knowledge and learning, both individual and organizational, are essential in this process (Sosna et al., 2010; Teece, 2010).

BMI is particularly valuable when firms supply foreign markets, since it helps companies to compete effectively against local competitors, gain local legitimacy, target new international market niches, and ultimately appropriate the created value (Merín-Rodrigáñez et al., 2024).

The international business literature has recognized the crucial role of BMI for international firms in achieving competitive advantage across borders (e.g., Evers et al., 2023; Merín-Rodrigáñez et al., 2024). While previous studies have produced different and sometimes conflicting results, most research converges on the idea that there is a positive relationship between BMI, internationalization, and international performance (e.g., Asemokha et al., 2020; Evers et al., 2023; Hennart et al., 2021; Krenn & Chiarvesio, 2024; al., 2022 should be replaced by Lew et al., 2023"?>Lew et al., 2023). Firms that innovate their business models, either before or during market entry, tend to be more successful in foreign markets (e.g., Asemokha et al., 2020; Christofi et al., 2024; Evers et al., 2023; Kraus et al., 2017). Empirical studies show that BMI is positively associated with higher international performance (Asemokha et al., 2020), business model design positively impacts international performance (Kraus et al., 2017), and BMI accelerates the internationalization process (Hennart et al., 2021) and increases the scope of internationalization (Lew et al., 2022).

An emerging stream of literature has been focused on the impact of crises on business models and, more specifically, BMI (e.g., Ritter & Pedersen, 2020; Salamzadeh et al., 2023). Crisis is recognized as one trigger of BMI (Attah-Boakye et al., 2023; Bashir et al., 2021), and BMI is considered an appropriate strategy to cope with crisis (e.g., Christofi et al., 2024; Salamzadeh et al., 2023).

In dynamic environments, such as the context of an economic crisis, a firm's BMI or adaptation strongly contributes to its performance (Ricciardi et al., 2016) and also its crisis management (Salamzadeh et al., 2023). In an international context, Christofi et al. (2024) found a positive relationship between BMI and international performance during the COVID-19 crisis.

Moreover, the concepts of exploration and exploitation have been integrated into the BMI literature. The balance between exploration and exploitation contributes to a better understanding of BMI (Ahokangas & Myllykoski, 2014). Throughout the lifespan of a business model, exploration and exploitation are interconnected, with exploitation being the result of exploration combined with learning (Ahokangas & Myllykoski, 2014). Sosna et al. (2010) discuss this relationship during the business model adaptation process, identifying two sequential phases: exploration followed by exploitation. The exploration phase involves the design, testing, and development of the business model, while the exploitation phase focuses on improving the model and sustaining growth through organizational learning. Subsequently, exploration reoccurs in response to various emerging triggers. Several authors (e.g., Colovic, 2022; Landau et al., 2014) have also observed this relationship in the context of business model adaptation to international markets.

Crisis impactGiven the current level of globalization, many companies are expanding their activities internationally (Acosta et al., 2018). As a result, events in one country can have far-reaching effects, affecting numerous other countries on a global scale. This interconnectedness was evident during the 2008 global financial crisis (e.g., Archibugi et al., 2013) and the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Osiyevskyy et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2020), both of which originated in specific locations but had far-reaching global effects.

An economic crisis can be defined as “an extreme, unexpected or unpredicted change in the external macroeconomic environment that requires an urgent response from firms and creates challenges and new threats for them” (Osiyevskyy et al., 2020, p. 228). The COVID-19 global crisis is an example of an abrupt and unforeseen change in both domestic and foreign markets. This situation is characterized by a group of environmental changes that misalign firms, potentially leading to a decline in performance (Håkonsson et al., 2013; Trahms et al., 2013). In addition, pre-existing plans may become infeasible due to adjustments in available resources, leading to a decline in performance as previous efforts fail to produce results (Shirokova et al., 2020). To navigate these periods, companies must adapt their strategies and goals (Martí, 2017; Osiyevskyy et al., 2020) and demonstrate flexibility to adapt to the new environment (Håkonsson et al., 2013). Strategic action by firms is crucial for long-term performance after a crisis, given the environmental changes that have occurred (Trahms et al., 2013).

The organizational decline and crisis literature shows that firms adopt a variety of responses to cope with a crisis including BMI (Christofi et al., 2024; Ritter & Pedersen, 2020), exploitation and exploration strategies (Archibugi et al., 2013; Iborra et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2024; Osiyevskyy et al., 2020), international dynamic marketing capabilities (Ciszewska-Mlinarič et al., 2024), market orientation, and entrepreneurial orientation (Beliaeva et al., 2020), among others. Moreover, the outcomes of these different responses are contingent on the firm's operating environment and crisis contexts (Håkonsson et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2024; Osiyevskyy et al., 2020). The existing literature demonstrates that different studies propose opposing solutions to crisis situations. Some advocate increased rigidity, while others recommend enhanced adaptability. Similarly, there is a debate over whether defensive strategies or proactive strategies should be adopted (Osiyevskyy et al., 2020).

A severe crisis, such as the global COVID-19 pandemic, can be an opportunity to seek new solutions and start the process of rethinking and adapting the current business model (Sosna et al., 2010). Shirokova et al. (2020) emphasize the importance of developing new strategies and building new capabilities to replace outdated approaches that may no longer be effective in the changed environment.

In the international context, both BMI and exploitation/exploration strategies are identified as effective solutions for coping with crises. Specifically, firms that innovate their business models are more likely to enhance their international performance (Asemokha et al., 2019). Additionally, during periods of high crisis severity, exploration strategies positively impact international performance whereas, under low severity conditions, exploitation strategies have a more significant positive effect (Osiyevskyy et al., 2020).

Dynamic capabilities viewThe resource-based view (RBV) is one of the most prominent theoretical frameworks for understanding how firms create and sustain competitive advantage over time (Barney, 1991, 2001). According to the RBV, firms are viewed as bundles of resources, including both tangible and intangible assets. The possession of valuable, rare, inimitable and non-substitutable resources leads to superior performance (Barney, 1991). The RBV emphasizes the utilization of productive resources in a relatively stable environment. However, this theory faces challenges when firms need to cope with high volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and competitive business environments that require firms to reconfigure their resources frequently (D'Aveni et al., 2010; Schilke, 2014).

This study employs the DCV to examine how exploitation/exploration strategies and BMI enable international firms to succeed in the extremely volatile environment of the COVID-19 global crisis. The DCV has been increasingly adopted in the literature to explain how firms overcome dynamic environments and achieve competitive advantage (Ambrosini & Bowman, 2009; Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Helfat et al., 2009; Schilke, 2014, 2018). Dynamic capabilities (DC) are defined as “the firm's ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments” (Teece et al., 1997, p. 516) to achieve competitive advantage (Schilke, 2014). Updating a company's competencies in response to quick changes in the industry environment constitutes dynamic capabilities. DC involve the sensing, seizing, and reconfiguration of firm resources and ordinary capabilities, which are essential for organizational adaptation processes (Helfat et al., 2009; Teece et al., 1997). During extreme turbulence and uncertainty, such as the 2008 global financial crisis (Ahn et al., 2018; Archibugi et al., 2013), a natural disaster (Martinelli et al., 2018), or a pandemic such as the COVID-19 (Crespo et al., 2024), firms utilize their dynamic capabilities to renew themselves. They sense the crisis, seize new opportunities, and reconfigure existing resources to survive and to enhance performance (Martinelli et al., 2018; Teece, 2007).

When companies have stronger dynamic capabilities, they can anticipate, sense, and understand the crisis in a timely manner and, therefore, are more likely to develop the most appropriate responses to react to that crisis (Ballesteros et al., 2017; Müller, 1985). These firms are also more prone to seize and identify new valuable opportunities in the context of a crisis (Ballesteros et al., 2017). Lastly, strong dynamic capabilities promote the firms’ capability to reconfigure and reorganize existing resources (internal or external) so as to manage the crisis in a way that enables the firm to survive and sustain its competitive advantage (Guo et al., 2020; Makkonen et al., 2014).

Conceptual framework and research hypothesesExploitation and exploration strategies and international business model innovationFirms can adapt their business model through exploration and exploitation (Kringelum & Gjerding, 2018). Here, it is possible to assume that both exploration and exploitation have a positive relationship with BMI. There are several empirical studies (Ahokangas & Myllykoski, 2014; Anzenbacher & Wagner; 2020; Smith et al., 2010) that confirm that exploration and exploitation strategies, in line with the dynamic capabilities view, affect the business model and its continuous adjustment. For instance, Ahokangas and Myllykoski (2014) establish the influence of exploration and exploitation in BMI, once it contributes to the evolution of the business model on both creation and transformation. Moreover, there is evidence that both strategies (exploration and exploitation) benefit the business model, with exploration being more beneficial in certain cases and exploitation in others (Anzenbacher & Wagner, 2020; Colovic, 2022). Sosna et al. (2010) note the existence of trial-and-error learning – which contemplates both exploration and exploitation – and its positive effect on the BMI. In light of the previous discussion, we argue that:

H1

Exploration is positively related to international BMI.

H2

Exploitation is positively related to international BMI.

As previously stated, both exploitation and exploration strategies compete for limited resources, requiring companies to achieve a balance between them (He & Wong, 2004; Shi et al., 2020). Ambidexterity is crucial for firms to survive in changing environments (Anzenbacher & Wagner, 2020). It is not viable for an organization to exclusively dedicate itself to one approach. Focusing solely on exploration prevents the organization from reaping the benefits of acquired knowledge, while an exclusive focus on exploitation can lead to obsolescence (Levinthal & March, 1993).

Since these strategies represent different approaches, they yield different effects and results (He & Wong, 2004). Exploitation generally produces better short-term results, whereas exploration yields better long-term outcomes (Levinthal & March, 1993; March, 1991; Uotila, 2017). Additionally, the returns from exploitation are more certain and immediate compared to those from exploration (He & Wong, 2004).

Nevertheless, during severe and profound crises, companies tend to support BMI primarily through exploration strategies rather than exploitation strategies (Osiyevskyy & Dewald, 2015; Sosna et al., 2010). There is evidence to suggest that firms pursuing exploration strategies manage crises more effectively (Archibugi et al., 2013; Clauss et al., 2022; Radziwon et al., 2022). For instance, exploration strategies focused on new product and market developments increase the likelihood of survival (Archibugi et al., 2013). These strategies require innovation in the business model to ensure value creation and delivery (Teece, 2010). Based on these arguments, we hypothesize that:

H3

The positive effect of exploration strategy with international BMI will be stronger than the effect of exploitation strategy.

International business model innovation and performanceThe international business literature shows that the majority of studies found a positive effect of BMI on internationalization performance measures (e.g., Asemokha et al., 2020; Evers et al., 2023; Hennart et al., 2021; Kraus et al., 2017; Krenn & Chiarvesio, 2024), in particular, in a crisis context (e.g., Christofi et al., 2024). Empirical studies show that BMI positively affects international performance (Asemokha et al., 2019; Lew et al., 2022) and contributes to accelerating the internationalization process (Hennart et al., 2021). For instance, Kraus et al. (2017) found that business model design has a positive effect on international performance. A recent literature review (Evers et al., 2023) also supports the positive performance outcomes of BMI in the international context. Similarly, Colovic (2022) verifies that business model adaptation contributes positively to performance. This author concludes that international businesses have to innovate their business models on a large scale in order to respond to the constant needs of international markets, and this innovation is positively related with different measures of international performance. In their study concerning distinct types of BMI, Heij et al. (2014) verified the positive effect of both replication and renewal on firm performance. Whereas the first one results in a constantly refined model that is harder to imitate, the second allows the firm to “protect or regain its market position and profitability in its existing markets” (Heij et al., 2014, p. 1506). A recent study (Christofi et al., 2024) found that, in the context of the COVID-19 crisis, BMI in the foreign market contributes to international performance. In their study with SMEs, Lew et al. (2023) found that BMI significantly mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial capability and SMEs' internationalization scope. Furthermore, when domestic market dynamism is high, the effect of BMI on internationalization scope is strengthened. Based on these arguments, we advance the following hypothesis:

H4

International BMI is positively related to international performance.

Several studies (e.g., Asemokha et al., 2019; Christofi et al., 2024) conclude that there is a positive relationship between BMI and international performance. Hence, BMI is expected to positively influence the expectation of crisis survival. Survival can be viewed as a measure of performance (Naidoo, 2010; Sinha & Noble, 2008). Thus, an examination of the effect of BMI on survival is proposed to confirm whether the relationship remains positive despite the conceptual differences between survival and international performance. A study developed with Italian manufacturing after the 2009 recession found that BMI positively contributes to post-crisis survival (Cucculelli & Peruzzi,2020). In the same vein, modification of the BM is among the possible successful strategies that SMEs can adopt to cope with the COVID-19 crisis, not only to aid survival but also to enhance internal operations (Akpan et al., 2023). Therefore, we argue that:

H5

International BMI is positively related to the expectation of crisis survival.

The hypotheses presented above can be organized in a comprehensive conceptual model (Fig. 1).

MethodologySample and data collectionThis study's data come from Portuguese firms with more than five employees and a positive percentage of exports in their total sales. The database of firms meeting these criteria was provided by Informa D&B (Dun & Bradstreet), which ensured the anonymity of the companies. This database included email addresses of 21,256 companies.

A questionnaire was designed and sent to the email addresses provided, accompanied by an invitation message for the owners, general managers, and export/international managers, explaining the study's purpose and requesting their participation. Before conducting the main study, a two-step approach was followed to review and revise the questionnaire. First, three academic experts in international business were consulted to assess the content validity of the scales. Based on their feedback, the questionnaire was revised. Then, the revised questionnaire was pilot tested with industrial experts through face-to-face semi-structured interviews. These interviews involved three export managers from different industry sectors, whose feedback further refined the questionnaire's content and wording.

The questionnaire was available on the LimeSurvey platform from March to April 2021. To increase the response rate, a four-step procedure was implemented (initial email plus three follow-ups). Out of the initial 21,256 contacts, 1832 emails bounced back, 1534 firms responded to the questionnaire, and 361 firms sent emails indicating they were unavailable or did not fit the sample criteria. After a screening process, 79 responses were eliminated due to lack of information about export activities or because the responses were unengaged. Consequently, the final number of valid responses was 1455 firms, resulting in a response rate of 7.7 % (1455/18,984).

The respondents are mainly men (59 %), and the age range is from 20 to 83 years old. The biggest percentage of respondents (approximately 39 %) is in the interval between 41 and 50 years old, followed by the interval between 51 and 60 years old (27.1 %). As regards the educational level, about 66 % of respondents have a college degree, 21.1 % completed high school, and 5.2 % have professional education. On positions within the firm, about 30 % are managing directors, chief executives or administrators, 29 % of the respondents are business owners, managing partners or CEOs and 28 % of the respondents are managers (responsible for the areas of sales, export, marketing or financial). Other positions considered are financial officers or certified accountants.

The majority of responding companies are family owned (69 %), with family management being the most common type (60 %). As regards the internationalization experience, approximately 13.8 % of the firms in the sample internationalized in the last five years, 20.9 % have an experience between 6 and 10 years, 34.3 % an experience between 11 and 20 years, and 31.0 % more than 20 years’ experience working in international markets. Regarding the degree of internationalization, measured as the weight of exports in the total turnover, almost 37 % of the sample show less than 5 % of exports, 20.4 % show a weight of exports between 5 % and 20 %, 22.6 % show a weight of the exports between 20.1 % and 60.0 %, and only 20.2 % of the companies export more that 60.1 %. Table 1 presents the sample characterization.

Sample characterization.

| Characteristics | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondents’ Position | Education level | ||||

| Business Owner | 330 | 22.7 % | Elementary school | 22 | 1.5 % |

| President/ CEO | 93 | 6.4 % | Junior high | 93 | 6.4 % |

| Administrator | 151 | 10.4 % | Professional education | 75 | 5.2 % |

| General Manager | 325 | 22.3 % | High School | 308 | 21.2 % |

| Senior Manager | 251 | 17.2 % | Bachelor | 588 | 40.4 % |

| Other | 305 | 21.0 % | Master degree | 191 | 13.1 % |

| Respondents’ Gender | Postgraduate degree | 162 | 11.1 % | ||

| Male | 858 | 59.0 % | PhD | 16 | 1.1 % |

| Female | 597 | 41.0 % | Founder | ||

| Respondents’ Age | Yes | 586 | 40.3 % | ||

| ≤30 years | 108 | 7.4 % | No | 869 | 59.7 % |

| 31–40 years | 268 | 14.4 % | Family Ownership | ||

| 41–50 years | 569 | 39.1 % | Yes | 997 | 68.5 % |

| 51–60 years | 394 | 27.1 % | No | 458 | 31.5 % |

| >60 years | 116 | 8.0 % | Family Management | ||

| Firm age | Yes | 876 | 60.2 % | ||

| ≤ 5 years | 69 | 4.7 % | No | 579 | 39.8 % |

| 6–10 years | 206 | 14.2 % | Number of employees | ||

| 11–15 years | 220 | 15.1 % | 6–10 employees | 522 | 35.9 % |

| 16–20 years | 164 | 11.3 % | 11–25 employees | 491 | 33.7 % |

| 21–30 years | 345 | 23.7 % | 26–50 employees | 237 | 16.3 % |

| 31–40 years | 223 | 15.3 % | 51–100 employees | 117 | 8.0 % |

| 41–50 years | 112 | 7.7 % | 101–250 employees | 62 | 4.3 % |

| 51–60 years | 53 | 3.7 % | > 250 employees | 26 | 1.8 % |

| > 60 years | 63 | 4.3 % | |||

| Firm's International Experience | Internationalization degree | ||||

| 1–5 years | 201 | 13.8 % | <5,0 % | 535 | 36.8 % |

| 6–10 years | 304 | 20.9 % | 5,0–10,0 % | 144 | 9.9 % |

| 11–15 years | 324 | 22.3 % | 10,1–20,0 % | 153 | 10.5 % |

| 16–20 years | 175 | 12.0 % | 20,1–40,0 % | 178 | 12.2 % |

| 21–30 years | 287 | 19.7 % | 40,1–60,0 % | 152 | 10.4 % |

| 31–40 years | 116 | 8.0 % | 60,1–80,0 % | 113 | 7.8 % |

| >40 years | 48 | 3.3 % | >80,1 % | 180 | 12.4 % |

The scales used to measure each construct were adopted from the existing literature (see Appendix A). All variables were assessed using multiple items.

Exploitation and exploration strategies were measured using a six-item scale adapted from Osiyevskyy et al. (2020). The five items used to measure international BMI were adapted from Asemokha et al. (2019), taking into account international markets and the context of the crisis period. International performance was measured using six items adapted from Knight and Cavusgil (2004) and Acosta et al. (2018). Expectations concerning crisis survival was measured using four items adapted from Naidoo (2010). All variables, except international performance, were measured using a Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree”). To measure international performance, two complementary perspectives were combined. First, a three-item scale was used to assess the expectation perspective, and respondents were asked to rate their satisfaction with the company's performance in international markets during the crisis period, taking into account their expectations at the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“extremely dissatisfied”) to 7 (“extremely satisfied”). On the other hand, a three-item scale accounts for the comparative perspective. Respondents were asked to rate how the company had performed in international markets during the crisis period compared to its main competitors since the start of the COVID-19 crisis, on a seven-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 (“Much worse”) to 7 (“Much better”).

The control variables considered in this study were firm size, firm age, international experience, and industry. Firm size is positively related to the international performance of firms, independent of considering financial or non-financial measures. On the other hand, firm age affects international performance negatively (Doğan, 2013; Vu et al., 2019). This last behavior is related to the fact that, over time, firms tend to be less dynamic, which can result in more difficulties when facing environmental changes. International experience, measured in years, was operationalized as the difference between the year the survey was launched (2021) and the year the company first internationalized (Sapienza et al., 2005). International experience is positively related to firm's survival and success (Mudambi & Zahra, 2007). Lastly, industry was measured as a dummy variable that assumes the value of “1′' if the firm belongs to a manufacturing sector and “0′' if the firm is from a non-manufacturing sector. Evidence in the literature indicates that different industries present different internationalization patterns, and different levels of international performance.

Non-response and common-method biasTo assess the normality of the data, the skewness and kurtosis measures were analyzed (Kline, 2015). According to Kline (2015), normality issues may arise when the skewness index exceeds |3.0| and the kurtosis index exceeds |10.0|. In this study, the skewness values ranged from 0.01 to 1.286, and the kurtosis values ranged from 0.02 to 2.046, both of which are within acceptable limits. Therefore, the data for this study have no normality problems.

To test for non-response bias, we compared the responses of early and late participants (the first 75 % versus the last 25 % of the sample), and we also compared respondents with non-respondents using a number of control variables. In both comparisons, the means of the variables were calculated and compared, and no significant differences were found. This indicates that non-response bias is not a potential problem.

With regard to common method bias, the Harman single factor test was performed. Problems can be considered to exist if a single factor explains the majority of the variance. The results of this study show six factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. The first factor accounts only for 29.18 % of the total variance, and the combined factors account for 72.46 % of the variance. These results suggest that common method bias is not an issue in this study.

Data analysis and resultsThe data was analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM) with the AMOS software, a method that allows for simultaneous testing of multiple relationships between various independent and dependent variables (Ullman & Bentler, 2012). SEM is considered a second-generation statistical analysis technique (Lowry & Gaskin, 2014) that has the ability to account for both random and systematic measurement errors (MacKenzie, 2001). Furthermore, SEM provides a more robust approach to assess reliability and validity (MacKenzie, 2001).

Assessment of measurement modelConfirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using maximum likelihood (ML) estimation was used to assess the reliability and validity of the constructs. The model fit indices were: χ²/df = 4.3041, GFI = 0.942, NFI = 0.962, CFI = 0.970, PGFI = 0.745 and RMSEA = 0.048. Except for the normed Chi-square, all goodness of fit indices exceeded the defined thresholds. Specifically, the RMSEA was below 0.07, while the CFI, GFI, and NFI were all above 0.9, and the PGFI exceeded 0.5 (Hair et al., 2018). Although the normed chi-square should typically be below 3.0, exceptions are made for large samples (greater than 750), as in the case of our study with a sample size of 1455 (Hair et al., 2018).

The standardized factor loadings, as shown in Appendix A, are generally above 0.7 (Hair et al., 2018). Appendix A shows the Cronbach's coefficient alphas (α), composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). The Cronbach's alpha and CR values both exceed the suggested threshold of 0.70, with the CR not exceeding 0.95 (Hair et al., 2018). The AVE values for each construct exceed the recommended threshold of 0.5 (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988, 2012) and are greater than the corresponding CR values, confirming convergent validity and internal consistency.

The Fornell–Larcker criterion was used to assess discriminant validity. This criterion compares the square root of the AVE for each construct with the correlations between that construct and all other constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The results, shown in Table 2, indicate that the square root of the AVE for each construct is higher than its highest correlation with any other construct, thus confirming discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Correlation Matrix.

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Exploration | 0.738 | ||||

| 2. | Exploitation | 0.711 | 0.745 | |||

| 3. | International BMI | 0.404 | 0.321 | 0.864 | ||

| 4. | International Performance | 0.144 | 0.153 | 0.464 | 0.831 | |

| 5. | Expectation about crisis survival | 0.215 | 0.259 | 0.113 | 0.25 | 0.894 |

Notes: Bolded numbers are the square roots of AVE.

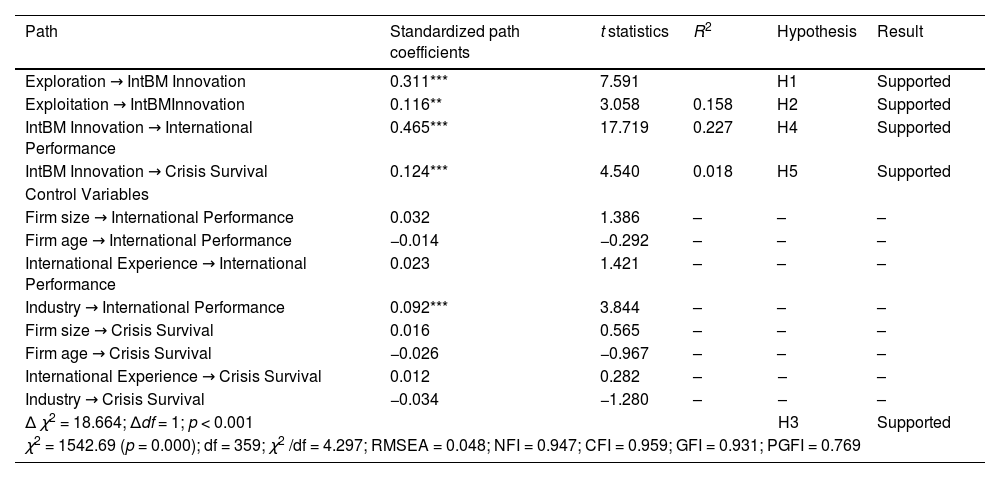

As analyzed for the measurement model, the validity of the structural model should also be assessed. As observed in the measurement model, the normed chi-square (4.297) is higher than the limit proposed (3.00) for the same reason as mentioned previously: the sample size dimension. The remaining indices present values within the limits suggested by the literature and, therefore, indicate a good fit of the model (χ2 /df = 4.297; CFI = 0.959, GFI = 0.931 NFI = 0.947, RMSEA = 0.048). The results of the structural model are presented in Table 3 below.

Results for structural model.

| Path | Standardized path coefficients | t statistics | R2 | Hypothesis | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exploration → IntBM Innovation | 0.311*** | 7.591 | H1 | Supported | ||

| Exploitation → IntBMInnovation | 0.116** | 3.058 | 0.158 | H2 | Supported | |

| IntBM Innovation → International Performance | 0.465*** | 17.719 | 0.227 | H4 | Supported | |

| IntBM Innovation → Crisis Survival | 0.124*** | 4.540 | 0.018 | H5 | Supported | |

| Control Variables | ||||||

| Firm size → International Performance | 0.032 | 1.386 | – | – | – | |

| Firm age → International Performance | −0.014 | −0.292 | – | – | – | |

| International Experience → International Performance | 0.023 | 1.421 | – | – | – | |

| Industry → International Performance | 0.092*** | 3.844 | – | – | – | |

| Firm size → Crisis Survival | 0.016 | 0.565 | – | – | – | |

| Firm age → Crisis Survival | −0.026 | −0.967 | – | – | – | |

| International Experience → Crisis Survival | 0.012 | 0.282 | – | – | – | |

| Industry → Crisis Survival | −0.034 | −1.280 | – | – | – | |

| Δ χ2 = 18.664; Δdf = 1; p < 0.001 | H3 | Supported | ||||

| χ2 = 1542.69 (p = 0.000); df = 359; χ2 /df = 4.297; RMSEA = 0.048; NFI = 0.947; CFI = 0.959; GFI = 0.931; PGFI = 0.769 | ||||||

Note: IntBMInnovation - International Business Model Innovation.

Significance was set at *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, and * p < 0.05.

The results show that exploration has a significant positive effect on international BMI (β = 0.311, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1 (H1). Similarly, exploitation has a significant positive effect on international BMI (β = 0.116, p < 0.01), supporting Hypothesis 2 (H2).

To test the hypothesized difference in the strength of the exploration and exploitation effects on international BMI, a chi-squared difference test was performed between the original model and a model in which both coefficients were constrained to be equal. The constrained model performed worse than the unconstrained model, and the difference was significant (p < 0.001). Thus, the difference between the effects of the exploration strategy (β = 0.311, p < 0.001) and the exploitation strategy (β = 0.116, p < 0.01) on international BMI is significant, supporting Hypothesis 3 (H3). This indicates that exploration strategy has a stronger relationship with international BMI than exploitation strategy.

Moreover, the results show that international BMI has a positive impact on international performance (β = 0.465, p < 0.001) and expectations concerning crisis survival (β = 0.124, p < 0.001), supporting Hypotheses 4 (H4) and 5 (H5), respectively.

Regarding the control variables, only the variable related to industry presents a positive and significant relationship with international performance (β = 0.092, p < 0.001), meaning that manufacturing firms exhibit better performances in the foreign markets than non-manufacturing firms.

Discussion of findingsIn line with the first research question of this study, we investigated how two different strategic approaches (exploration and exploitation) of internationalized firms affect their international business model innovation during a global crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

We found that both exploration and exploitation strategies enhance international BMI. Although this relationship has been previously investigated in the literature (Ahokangas & Myllykoski, 2014; Anzenbacher & Wagner, 2020; Colovic, 2022; Smith et al., 2010), research assessing how international firms react to a major crisis is still scarce (Attah-Boakye et al., 2023; Christofi et al., 2024; Evers et al., 2023; Lew et al., 2023). Furthermore, while there are some studies assessing the role of exploration, exploitation, and ambidexterity strategies during a crisis period (e.g., Beliaeva et al., 2020; Chou et al., 2024; Iborra et al., 2020), the focus is placed on performance effects, neglecting the impact on international BMI.

Hence, this study is distinct in examining the way those strategies relate to international BMI during an unstable period. The results of this study are consistent with previous works (e.g., Ahokangas & Myllykoski, 2014; Anzenbacher & Wagner, 2020), showing a positive significant effect of both strategies on international BMI among Portuguese firms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, the results support Colovic's (2022) conclusions regarding this relationship in the international context, showing that these effects are consistent with those observed by other authors in the domestic context.

Concerning our first research question, we found that the effects of these strategies on international BMI are not identical. Previous studies comparing the effectiveness of exploration and exploitation strategies on firm performance have produced contradictory results (Shi et al., 2020). While some studies conclude that both strategies can generate higher performances when combined with an ambidextrous strategy (e.g., He & Wong, 2004; Shi et al., 2020), others suggest that focusing solely on one of these strategies has a better result than combining both strategies (Gupta et al., 2006; Junni et al., 2013). Furthermore, the existent literature has shown that the effectiveness of exploration and exploitation strategies depends on crisis severity (Osiyevskyy et al., 2020). Our findings suggest that, in a severe crisis situation, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the effect of the exploration strategy on international BMI is stronger than that of the exploitation strategy. This result is consistent with the finding of Jansen et al. (2006) that concludes that an exploration strategy achieves better results when in a highly dynamic environment. Moreover, this result is aligned with other studies that argue that, in a severe and profound crisis context, an exploration strategy is preferred by companies to enhance their BMI (Osiyevskyy & Dewald, 2015; Sosna et al., 2010). Based on the discussion that following a single strategy may generate different effects and results (He & Wong, 2004), some authors (e.g., Levinthal & March, 1993; Uotila, 2017) argue that the exploitation strategy usually produces better results in the short term while the exploration strategy performs better in the long term. Our results indicate that exploration strategies are more effective in dealing with crises (Archibugi et al., 2013; Clauss et al., 2022; Radziwon et al., 2022). By following the reasoning of previous authors (e.g., Shirokova et al., 2020; Sosna et al., 2010), a severe crisis could present an opportunity for firms to seek new business model solutions and to develop new strategies with a longer time horizon.

Regarding the second research question, we examined the effect of international BMI on international performance and expectations concerning crisis survival during the COVID-19 crisis. Our findings show a positive relationship between international BMI and international performance during the COVID-19 crisis, which is consistent with the existing literature. For example, Asemokha et al. (2019) observed this relationship in the context of SMEs, and other authors (Colovic, 2022; Heij et al., 2014; Lonial & Carter, 2015) noted that maintaining competitive advantage motivates BMI. The existing literature in international business shows that BMI increases international scope (e.g., Lew et al., 2022), accelerates the internationalization process (Hennart et al., 2021) and is an appropriate reaction to handle a crisis (e.g., Christofi et al., 2024; Salamzadeh et al., 2023) and increase international performance (e.g., Asemokha et al., 2020; Kraus et al., 2017). Furthermore, our results demonstrate that international BMI is positively related to expectations concerning crisis survival. The previous literature has explored the relationship between BMI and crisis survival in a national environment (e.g., Cucculelli & Peruzzi, 2020; Naidoo, 2010), neglecting to undertake its examination in an international context (Akpan et al., 2023). Therefore, our study expands existing knowledge by offering evidence that international BMI not only enhances international performance but also heightens expectations concerning survival of the firm.

Conclusion, limitations, and further researchThis study aimed to elucidate the role of exploitation and exploration strategies in promoting international BMI and how international BMI contributes to international performance and expectations concerning crisis survival. The results indicate that both strategies contribute significantly to international BMI in the context of a severe crisis, with exploration strategies having a significantly higher impact. Furthermore, the results show that international BMI improves international performance and strengthens expectations concerning crisis survival.

Theoretical contributionsThis study makes three important contributions to the international business and crisis management literature. First, it provides a nuanced understanding of the role of exploitation and exploration strategies when international firms face an extreme crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. While the effectiveness of exploitation, exploration, and ambidexterity strategies has been extensively studied in management (Gupta et al., 2006; He & Wong, 2004; Junni et al., 2013; Kang & Kim, 2020; Shi et al., 2020), international business (Jin et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2022; Ruano-Arcos et al., 2024; Sousa et al., 2020) and crisis literature (Archibugi et al., 2013; Beliaeva et al., 2020; Chou et al., 2024; Iborra et al., 2020), few studies have focused on the role of these strategies during an extreme crisis, such as COVID-19 (Kim et al., 2024; Osiyevskyy et al., 2020; Radziwon et al., 2022). Of these, only one specifically addresses the international context (Osiyevskyy et al., 2020). Our study shows that both strategies are crucial for international firms facing extreme shocks, with exploration strategies proving to be more effective.

Second, we contribute with new insights on BMI drivers. Thus far, the BMI literature has contributed significantly to a better understanding of the triggers, drivers, and outcomes of BMI (e.g., Bashir et al., 2021; Foss & Saebi, 2017; Zhang et al., 2024) and has supported the important role of BMI in the international (Christofi et al., 2024; Evers et al., 2023; Merín-Rodrigáñez et al., 2024), and crisis contexts (Christofi et al., 2024; Ritter & Pedersen, 2020; Salamzadeh et al., 2023). The drivers of international BMI in an extreme crisis context are a nascent area of research that requires further investigation (Christofi et al., 2024). Our study provides evidence of international BMI drivers in a crisis context. More specifically, we found that exploration and exploitation strategies leverage international BMI.

Third, our study enhances understanding of the BMI-performance relationship. While this relationship has been supported in several empirical studies in both domestic (Bashir et al., 2021; Foss & Saebi, 2017; Zhang et al., 2024) and international markets (Evers et al., 2023; Lew et al., 2023), how it works in an extreme crisis context is clearly not understood, with only one empirical study supporting it (Christofi et al., 2024). Our study reinforces the positive impact of BMI on international performance—more specifically, on international BMI. Moreover, our findings demonstrate that international BMI has a positive effect on survival—in particular, expectations concerning crisis survival.

Managerial implicationsOur study provides guidance for international business managers dealing with extreme crises. First, our findings help managers to choose an appropriate adaptation strategy when faced with a crisis or a highly turbulent environment. In extremely uncertain and unpredictable environments, managers need to rely on both exploration and exploitation strategies to innovate their international business model. In order to respond to a crisis, internationalised firms need to innovate their international business model. They can support this change by developing new knowledge, fostering innovation and finding new opportunities to enter new markets, developing new products and processes (exploration), or by refining existing knowledge and competencies to execute existing processes and products more efficiently (exploitation).

Second, albeit riskier, managers should put greater emphasis on exploration practices because they strongly contribute to the innovation of their international business model.

Third, managers are incentivised to innovate their international business model in an extremely dynamic environment because it allows them to achieve better levels of performance in foreign markets and increase expectations of surviving the crisis. Since BMI in foreign markets is more complex due to greater pressures, uncertainties in dealing with different local requirements, and changing foreign market conditions, managers are encouraged to build and improve their firm's dynamic capabilities.

Limitations and future researchThis study, as with any research, has certain limitations, which require some caution in interpreting the findings. First, the data come only from Portuguese firms, which limits generalizability of the results. The way companies in different countries react to a crisis, and particularly to COVID-19 crisis, could well be different (Van Assche & Lundan, 2020).

Second, the cross-sectional nature of the study is a limitation. The effects of the crisis may take time to materialize. Data collection occurred in the period between March and April 2021. At that time, the overall consequences and effects of the crisis were still unknown. Moreover, our data collection approach failed to avoid a loss of information caused by firm failures, introducing the potential risk of survival bias. The use of a single respondent per organization and the perceptual nature of the data can affect common method bias.

Future studies should address these caveats, testing the model with data from multiple countries, including multiple respondents in each firm, collecting data after the pandemic and using objective measures of performance. Moreover, our model could be tested using data from a period of economic grow to reinforce the idea that, in periods of extreme uncertainty, companies need to revise their exploitation and exploration strategies, as well as their international BMI.

Third, our model could be used to evaluate the effect of international BMI on other outcomes such as resilience (Castello-Sirvent et al., 2023; Iborra et al., 2020), competitive advantages, operational changes, and business model innovativeness. Other factors that could be included to better understand the effectiveness of exploitation and exploration strategies are the level of innovation before the crisis (Archibugi et al., 2013) and the industrial context (e.g., Chou et al., 2024). Digital technologies are recognized as a critical resource for firms to maintain their competitive advantage (Nyagadza, 2022) and to navigate through extreme, uncertain environments, such as the COVID-19 crisis (Crespo et al., 2024). The inclusion of digital technology capabilities as a precursor to international BMI in our conceptual model represents an important avenue for future research and holds out the prospect of enriching the international BMI literature.

Fourth, the research design of this study was based on the assumption that including firms from a multi-industry sample would likely exert a positive impact on the generalizability of the results. Nevertheless, exploring the implementation of innovation strategies and international BMI in different industries may lead to different results. Hence, future studies may wish to conduct comparative analysis between industries to assess the existence of possible nuances.

FundingWe gratefully acknowledge the financial support from FCT (Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia – Portugal) under projects UIDB/SOC/04521/2020 and UIDB/04928/2020.

CRediT authorship contribution statementNuno Fernandes Crespo: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Cátia Fernandes Crespo: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation. Graça Silva: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation. Beatriz Barros: Writing – original draft, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

| Items | Description | Standardized loadings | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exploration (α = 0.87; CR = 0.86; AVE = 0.54) “Since the beginning g of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, our firm can be described as one that…”(Scale: 1 = ‘Strongly disagree’; 4 = ‘Neither agree or disagree’; 7 = ‘Strongly agree’) | |||

| Explor_it1 | looks for novel technological ideas by thinking “outside the box”. | 0.772 | |

| Explor_it2 | bases its success on its ability to explore new technologies. | 0.780 | |

| Explor_it3 | creates products or services that are innovative to the firm. | 0.817 | |

| Explor_it4 | looks for creative ways to satisfy its customers’ needs. | 0.729 | |

| Explor_it5 | aggressively ventures into new market segments. | 0.657 | |

| Explor_it6 | actively targets new customer groups. | 0.607 | |

| Exploitation (α = 0.84; CR = 0.86; AVE = 0.56) “Since the beginning g of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. our firm can be described as one that…”(Scale: 1 = ‘Strongly disagree’; 4 = ‘Neither agree or disagree’; 7 = ‘Strongly agree’) | |||

| Exploi_it1 | commits to improve quality and lower cost.a | – | |

| Exploi_it2 | continuously improves the reliability of its product and services. | 0.759 | |

| Exploi_it3 | increases the levels of automation in its operations. | 0.627 | |

| Exploi_it4 | constantly surveys existing customers’ satisfaction. | 0.722 | |

| Exploi_it5 | fine-tunes what it offers to keep its current customers satisfied. | 0.879 | |

| Exploi_it6 | penetrates more deeply into its existing customer base. | 0.716 | |

| International Business Model Innovation (α = 0.94; CR = 0.94; AVE = 0.75)Considering the company's business model in the international markets in which it operates. indicate your degree of agreement. with the statements below:(Scale: 1 = ‘Strongly disagree’; 4 = ‘Neither agree or disagree’; 7 = ‘Strongly agree’) | |||

| BMA_it1 | During the COVID-19 crisis. our firm was able to perform significant intern reconfigurations. to improve the value proposition to international clients. | 0.835 | |

| BMA_it2 | Because of the COVID-19 crisis. our firm was able to identify international opportunities. managing to reorganize its operational processes quickly. | 0.895 | |

| BMA_it3 | During the COVID-19 crisis. our firm was able to rearrange its partners network. in order to improve the value proposition presented to international clients. | 0.880 | |

| BMA_it4 | During the COVID-19 crisis. the new opportunities to serve international clients were quickly understood by our firm. | 0.865 | |

| BMA_it5 | Considering the challenges of this crisis. our firm identified innovative opportunities to adapt the pricing models used in international markets. | 0.844 | |

| International Performance (α = 0.94; CR = 0.93; AVE = 0.69)(A) Considering your initial expectations when the COVID-19 crisis began. rate your degree of satisfaction with the performance that your company has had in international markets during this period of crisis:(Scale: 1 = ‘Extremely unsatisfied’; 4 = ‘Neutral’; 7 = ‘Extremely satisfied’)(B) Compared to its closest competitors since the COVID-19 crisis began. how has it performed in international markets during this period of crisis:(Scale: 1 = ‘Much worse’; 4 = ‘Similar’; 7 = ‘Much better’) | |||

| IntPerf_itA1 | Expression of international markets on the firm's sales revenue. | 0.908 | |

| IntPerf_itA2 | Growth in the international markets we operate in. | 0.919 | |

| IntPerf_itA3 | Results before taxes in the international markets. | 0.933 | |

| IntPerf_itB1 | Growth of sales in international markets. | 0.752 | |

| IntPerf_itB2 | Return of the investment on international markets. when compared to domestic markets. | 0.725 | |

| IntPerf_itB3 | Success of new products in international markets. | 0.709 | |

| Crisis Survival (α = 0.91; CR = 0.92; AVE = 0.80)Evaluate the performance that your company will have during the current COVID-19 crisis. indicating your degree of agreement with the statements below:(Scale: 1 = ‘Strongly disagree’; 4 = ‘Neither agree or disagree’; 7 = ‘Strongly agree’) | |||

| CSurv_it1 | Our firm will survive to the current COVID-19 crisis. | 0.918 | |

| CSurv_it2 | Our firm is capable to overcome the challenges of the current COVID-19 crisis. | 0.977 | |

| CSurv_it3 | Our firm is positively positioned to face up to the slowdown of the business activity currently existing. due to the COVID-19 crisis. | 0.775 | |

| CSurv_it4 | Our sales revenue decreased in the last months due to the COVID-19 crisis. but the level of sales will return to the pre-crisis level. a | – | |

Notes: a – This item was deleted during the scale purification process.