To compare the 30-day outcome (mortality and/or ICU admission) of patients admitted for moderate-severe SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia treated with dexamethasone after the Recovery study versus those treated with weight-adjusted methylprednisolone.

MethodsRetrospective cohort study of 65 patients with moderate-severe pneumonia who received dexamethasone 6mg/day (DXM group) versus 80 treated with weight-adjusted methylprednisolone (MTPN group)

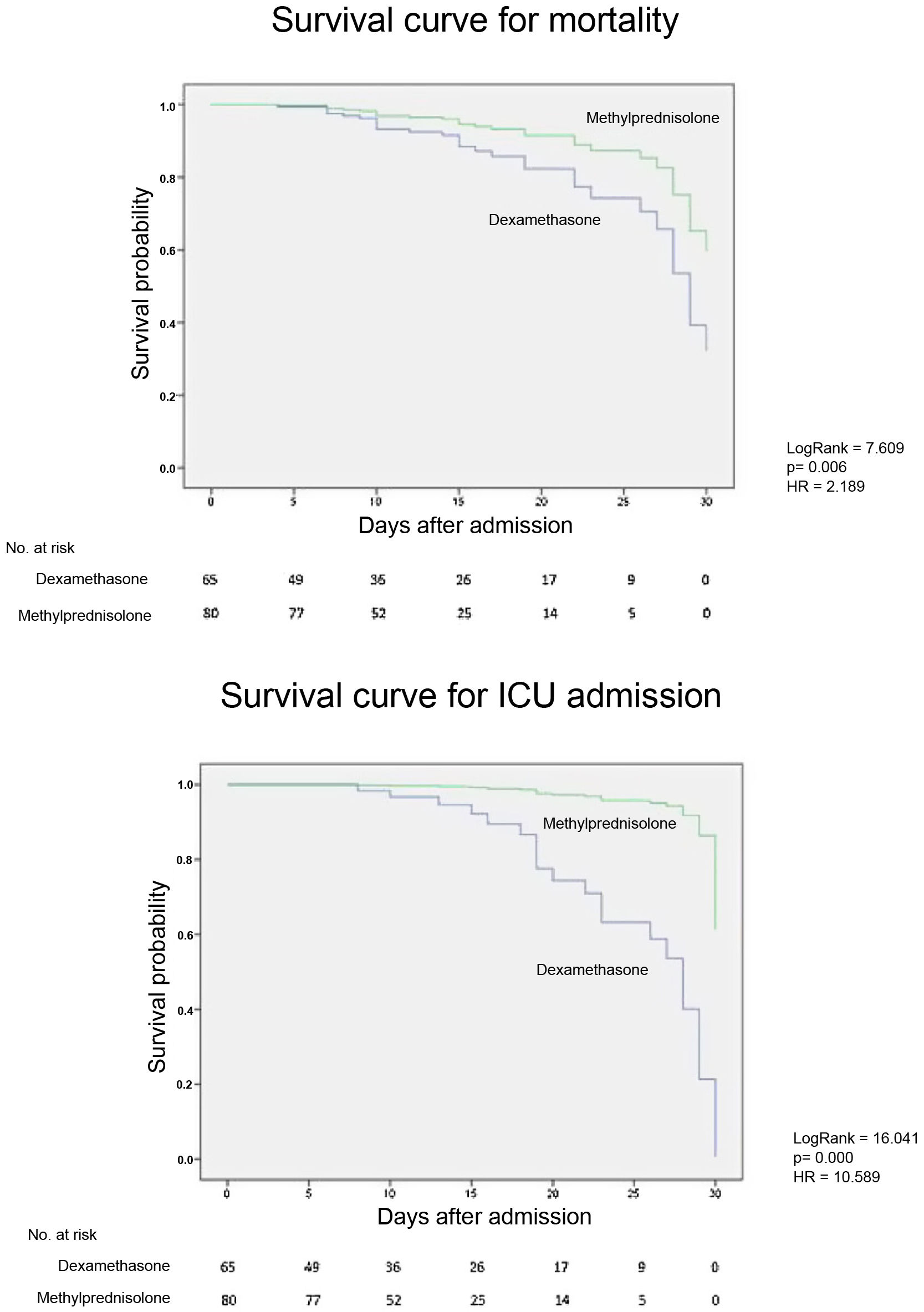

Results21 (32.3%) patients in the DXM group died vs 8 (10%) in the MTPN group (p-value < 0.001) and 29 (44.6%) in the DXM group required ICU admission vs 2 (2,5%) of the MTPN group (p-value <0.001). There were no baseline differences regarding sociodemographic characteristics with a higher mean qSOFA in the MTPN group. The hazard ratio for mortality and ICU admission adjusted for age, sex, and admission CRP was 2.189 (1.082–4.426; 95% CI) and 10.589 (2.139–48.347; 95% CI) for the DXM group, respectively, vs. MTPN group.

ConclusionsMortality and admission to the ICU were lower in patients treated with weight-adjusted methylprednisolone compared to those treated with dexamethasone.

Comparar el desenlace clínico (mortalidad y/o ingreso en UCI) a 30 días de los pacientes ingresados por neumonía moderada-grave por SARS-CoV-2 tratados con dexametasona tras el estudio Recovery frente aquellos tratados con metilprednisolona ajustada al peso.

MétodosEstudio de cohortes retrospectivo de 65 pacientes con neumonía moderada-grave que recibieron 6mg/día de dexametasona (grupo DXM) frente a 80 tratados con metilprednisolona ajustada al peso (grupo MTPN).

ResultadosFallecieron 21 (32,3%) pacientes del grupo DXM vs 8 (10%) del grupo MTPN (p-valor<0,001) y 29 (44,6%) del grupo DXM requirieron ingreso en UCI vs 2 (2,5%) del grupo MTPN (p-valor<0,001). No hubo diferencias basales respecto a características sociodemográficas con un qSOFA medio superior en el grupo MTPN. La razón de riesgo para la mortalidad y el ingreso en UCI ajustada por edad, sexo y PCR al ingreso fue de 2,189 (1,082−4,426; IC 95%) y 10,589 (2,139−48,347; IC 95%) para el grupo DXM, respectivamente, vs grupo MTPN.

ConclusionesLa mortalidad e ingreso en UCI fue menor en pacientes tratados con metilprednisolona ajustada al peso frente a los tratados con dexametasona.

Dexamethasone (DXM) has been shown to reduce mortality in patients with moderate/severe SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia requiring oxygen therapy, which has led to its widespread use as initial treatment in most protocols.

The hyperinflammatory phase in these patients results from dysregulation of the immune response with a significant increase in acute phase reactants leading to clinical worsening, usually on the sixth to tenth day after symptom onset. Corticosteroids are adjusted to the patient's weight in the treatment of many inflammatory diseases and this was done during the early months of the pandemic. Evidence of lower mortality associated with the use of high-dose methylprednisolone (MTP) has been available since March 2020.1 After the publication of the Randomised evaluation of COVID-19 therapy (RECOVERY),2 this protocol was modified to recommend administration of fixed doses of 6mg/day of dexamethasone for ten days. Following this change, our impression in clinical practice was that in many patients this dose of dexamethasone was insufficient and led to a worse outcome. We therefore set out to analyse the 30-day clinical outcome (mortality and/or ICU admission) of the first 65 patients who received dexamethasone compared to a historical cohort who had received weight-adjusted methylprednisolone.

MethodsBetween 1 and 31 December 2020 we retrospectively collected data on 65 elderly patients admitted to the Hospital Clínico de Granada with moderate/severe SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia confirmed by nasopharyngeal swab PCR requiring oxygen therapy who received 6mg/day dexamethasone within the first 24h of admission in addition to standard treatment including remdesivir if criteria were met and low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) at therapeutic doses. They were compared with a historical cohort of patients admitted to our hospital between 15 March and 15 May 2020 treated within the first 24h of admission with weight-adjusted MTP together with standard treatment consisting of azithromycin, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir/ritonavir and LMWH. Our protocol in this period included the use of weight-adjusted methylprednisolone with tapering over 15 days (1−2mg/kg/day IV of MTP for three to five days; then 40mg/day for three days, 30mg/day for three days, 20mg/day for three days and finally 10mg/day for three days).

A total of 129 patients were admitted in the first period and 91 in the second. Patients admitted directly to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) were excluded from the study.

On admission, all patients had a duration from symptom onset between six and 11 days (median 7 and interquartile range 5–10 days). Comorbidities and SO2/FiO2 on admission were collected and CURB-65 and quick sepsis related organ failure assessment (qSOFA) indices were calculated. Laboratory data analysed were ferritin, CRP, fibrinogen, D-dimer and procalcitonin. We analysed the extent of pneumonia based on chest X-ray or computed tomography (CT), according to the guidelines of the British Society of Thoracic Imaging (BSTI) classification system. The clinical outcome was compared between both groups at 30 days.

After the descriptive analysis, differences between the variables were studied. For the qualitative variables, the χ2 test was used to compare proportions. The normal distribution of the quantitative variables was analysed by means of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to estimate significant differences in those variables derived from independent populations that did not have a normal distribution and Student's t test to compare the means of independent populations in variables that had a normal distribution. The Wilcoxon test was used to compare paired samples from non-normal populations. Two Cox regressions were performed separately to calculate the hazard ratio for mortality and ICU admission of one group compared to another. These were corrected for age, gender and CRP at admission, adding Kaplan–Meier survival curves. The statistical software used was SPSS Version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

The study was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki declaration, obtaining the favourable opinion of the IRB/IEC of the Granada County.

ResultsBaseline characteristics, comorbidities, radiographic involvement, qSOFA, CURB-65 are shown in Table 1. The laboratory data and clinical outcome are shown in Table 2.

Baseline characteristics, comorbidities, degree of radiological involvement and severity indices on admission.

| Dexamethasone (n=65) | Methylprednisolone (n=80) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | χ2 (p-value) | |

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Age (> 65) | 40 (61.5%) | 49 (61.25%) | 0.001 (0.972) |

| Sex (male) | 28 (43.1%) | 45 (56.25%) | 2.489 (0.115) |

| HBP | 44 (67.7%) | 39 (48.75%) | 5,525 (0,022*) |

| COPD/asthma | 6 (9.2%) | 18 (22.50%) | 4,572 (0,033*) |

| Obesity | 17 (26.2%) | 33 (41.25%) | 3.618 (0.057) |

| Isch. heart disease | 4 (6.2%) | 4 (5%) | 0.092 (0.762) |

| Heart failure | 10 (7.2%) | 8 (10%) | |

| Diabetes | 19 (29.2%) | 13 (16.25%) | 3.514 (0.061) |

| Renal I. | 10 (15.4%) | 11 (13.75%) | 0.077 (0.781) |

| Multilobar infiltrate | 50 (76.9%) | 61 (76.3%) | 5.391 (0.068) |

| TC involvement (moderate or severe) | 25 (86.2%) n = 25 | 28 (75.7%) n=37 | |

| Anticoagulation | 6 (16.7%) | 6 /7.5%) | 2.249 (0.134) |

| Min, Max, Q1, Q2, Q3 | Min, Max, Q1, Q2, Q3 | OR Mann-Whitney test (p value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CURB-65 | 0, 3, 1, 2, 2 | 0, 5, 1, 2, 2 | 2,382.500 (0.341) |

| qSOFA | 0, 7, 1, 2, 3 | 0, 3, 0, 0, 1 | 556.000 (0.000**) |

HBP, high blood pressure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CT, computed tomography; CURB-65, mortality prediction scale used in patients with community-acquired pneumonia; qSOFA, quick sequential organ failure assessment; Min: minimum value; Max, maximum value; Q1, first quartile; Q2, median or second quartile; Q3, third quartile, x¯, mean; Sx, standard deviation.

Primary outcomes, mean hospital stay and laboratory characteristics at baseline and after three days of treatment in the different treatment groups.

| Dexamethasone (n=65) | Methylprednisolone (n=80) | Group comparison: dexamethasone/methylprednisolone | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcomes | χ2 (p-value) | |||||

| ICU admission | n (%) | 29 (44.6%) | 2 (2.5%) | 37.843 (0.000***) | ||

| Intubation | n (%) | 23 (35.4%) | 2 (2.5%) | 27.179 (0.000***) | ||

| Death | n (%) | 21 (32.3%) | 8 (10%) | 15.347 (0.000***) | ||

| Student's t test (p-value) | ||||||

| Average hospital stay | x¯sx | 13.029 (7.469) | 14.722 (6.174) | −1.230 (0.221) | ||

| Laboratory characteristics | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Mann-Whitney's U test (p value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferritin Min | 80.000 | 52.800 | 105.900 | 79.000 | Pre: 1,804.500 (0.002**) | |

| Max | 4,450.000 | 4,500.000 | 3,772.000 | 4,332.400 | Post: 2,032.000 (0.034*) | |

| Q1 | 214.950 | 250.950 | 472.200 | 539.650 | ||

| Q2 | 442.900 | 558.550 | 686.200 | 702.550 | ||

| Q3 | 830.100 | 1,036.850 | 1,087.225 | 995.200 | ||

| Wilcoxon's Z (p-value) | −2.030 (0.042*) post>pre | −2.053 (0.040*) post>pre | ||||

| D-dimer | ||||||

| Min | 0.190 | 0.240 | 0.190 | 0.190 | Pre: 2,531.000 (0.907) | |

| Max | 11.660 | 23.580 | 333.000 | 117.000 | Post: 2,420.500 (0.807) | |

| Q1 | 0.573 | 0.615 | 0.575 | 0.590 | ||

| Q2 | 0.910 | 1.315 | 0.865 | 1.255 | ||

| Q3 | 2.158 | 2.703 | 1.910 | 2.805 | ||

| Wilcoxon's Z (p-value) | −1.221 (0.222) | −1.432 (0.152) | ||||

| Lymphocytes | ||||||

| Min | 330 | 190 | 250 | 220 | Pre: 2,120.500 (0.057) | |

| Max | 9,200 | 3,350 | 3,800 | 4,550 | Post: 2,422.000 (0.479) | |

| Q1 | 575 | 535 | 705 | 607,5 | ||

| Q2 | 800 | 780 | 940 | 820 | ||

| Q3 | 1,130 | 1,165 | 1,267,5 | 1,227 | ||

| Wilcoxon's Z (p-value) | −0.023 (0.932) | −0.705 (0.481) | ||||

| CRP | ||||||

| Min | 5.700 | 4.100 | 3.900 | 0.800 | Pre: 2,114.500 (0.054) | |

| Max | 531.000 | 297.800 | 346.200 | 366.100 | Post: 1,392.500 (0.000**) | |

| Q1 | 54.300 | 29.200 | 37.025 | 8.350 | ||

| Q2 | 113.500 | 70.700 | 78.100 | 19.950 | ||

| Q3 | 177.450 | 124.950 | 143.625 | 68.125 | ||

| Wilcoxon’s Z (p-value) | −3.950 (0.000**) post<pre | −6.737 (0.000**) post<pre | ||||

| PCT | ||||||

| Min | 0.020 | 0.020 | Pre: 2,500.000 (0.510) | |||

| Max | 10.800 | 2.030 | ||||

| Q1 | 0.065 | 0.060 | ||||

| Q2 | 0.120 | 0.080 | ||||

| Q3 | 0.390 | 0.160 | ||||

Pre, pre-treatment; Post, post-treatment; PCT, procalcitonin; Min, minimum value; Max, maximum value; Q1, first quartile; Q2, median or second quartile; Q3, third quartile; x¯, mean; Sx, standard deviation.

Twenty-one (32.3%) patients in the DXM group died vs. eight (10%) in the MTP group (p-value=0.000); 29 (44.6%) in the DXM group required ICU admission vs. two (2.5%) in the MTP group (p-value=0.000); 34 (52.3%) in the DXM group required rescue therapy for respiratory worsening vs. two (2.5%) in the MTP group. There was no association between the clinical outcome and the rescue therapy used. Of the rescued patients in the DXM group, 23 (67.6%) were discharged after 30 days and 11 (32.4%) died. The two rescued patients from the MTP group were discharged. The mean cumulative dose of MTP received by patients in the MTP group was 756mg.

Cox regression for mortality and ICU admission adjusted for treatment group, age, sex and CRP at admission gave a hazard ratio of 2.189 (1.082–4.426, 95% CI) and 10.589 (2.139–48.347, 95% CI) respectively for the DXM group over the MTP group (Fig. 1). Patients treated with dexamethasone are more than twice as likely to die and more than ten times as likely to be admitted to the ICU than those treated with MTP.

DiscussionImmunomodulatory drugs such as anakinra,3 tocilizumab,4 baricitinib,5 corticosteroids or immunoglobulins6,7 are used to control the hyperinflammatory phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Clinical trials like CoDEX8 and RECOVERY2 have shown a reduction in mortality with the use of dexamethasone. In RECOVERY, this reduction in the group of patients with oxygen therapy without invasive mechanical ventilation was 23.3% vs. 26.2%; in those with mechanical ventilation the reduction was greater (29.3% vs. 41.4%). The fact that all patients in our study met the criteria for hyperinflammation probably contributed to the higher mortality in the DXM group (32%) compared to RECOVERY (23.3%) which did not consider this aspect. The great difference observed in mortality (22%) between our historical cohort treated with methylprednisolone9 and the DXM group makes us reflect on the possible negative impact in terms of mortality due to the modification of treatment protocols after the RECOVERY trial, given that many hospitals replaced high-dose methylprednisolone with fixed-dose dexamethasone. It is interesting to note the separation of the survival curves from the sixth to the eighth day, which could be a consequence of a more effective early blockade of the cytokine storm -"window of opportunity" - in the MTPN group. Similar to the literature, the factors associated with worse prognosis in our study were age, elevated CRP and ferritin levels at admission. Although CRP at admission was higher in the DXM group, and this could explain a moderate increase in mortality, all other laboratory characteristics and SO2/FiO2 at admission were similar between the two groups. Comorbidities were evenly distributed, except for high blood pressure (HBP), which was higher in the DXM group, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which was higher in the MTP group.

Our data are consistent with a recently published study,10 in which administration of i.v. methylprednisolone for three days followed by an oral tapering regimen of prednisone for 14 days was superior to 6mg/day of dexamethasone with a 30-day survival of 92.6 vs. 63.1%.

The limitations of this study lie in its single-centre nature, its small sample size and the intrinsic characteristics of observational studies. We consider the application of the same therapeutic protocol in each time period to be a strength, especially since the MTP group's protocol included drugs with no benefit or even possible harmful effects.

In conclusion, our study suggests a worse outcome with fixed-dose 6mg/day dexamethasone compared to weight-adjusted methylprednisolone in patients with moderate-severe SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia and hyperinflammation. A randomized clinical trial comparing both treatment arms would be necessary to confirm these differences.

FundingThis study has not received any funding.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.