Previous studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic in other countries have shown an increase in symptoms associated with mental health problems in healthcare professionals.1 Most of these studies have focused on risk factors and fewer on protective factors. Additionally, a large part of them have been carried out abroad.

Therefore, we propose to study the prevalence of mental health problems in a sample of Spanish health professionals, and the associated risk factors, as well as to know if psychological capital or any of its factors acts as a protective resource in the context of the pandemic.

To this end, a survey was designed and submitted electronically. The sample was collected through a snowball sampling procedure and it consisted of 294 healthcare professionals in contact with SARS-CoV-2 infected patients.

To study the prevalence of mental health problems, the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), 12-item version, was used. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.857. To correct the test, the GHQ score was used, more appropriate when the objective is to diagnose cases. Following the recommendations of Goldberg et al.,2 and considering that the mean of the present study is 4.73, the cut-off point was established at 3. The psychological capital scale was used to measure psychological capital,3 a 16-item scale, consisting of 4 factors: resilience (alpha = 0.684); hope (alpha = 0.809); optimism (alpha = 0.705) and self-efficacy (alpha = 0.779). Data collection took place during the period of lockdown (April 2020).

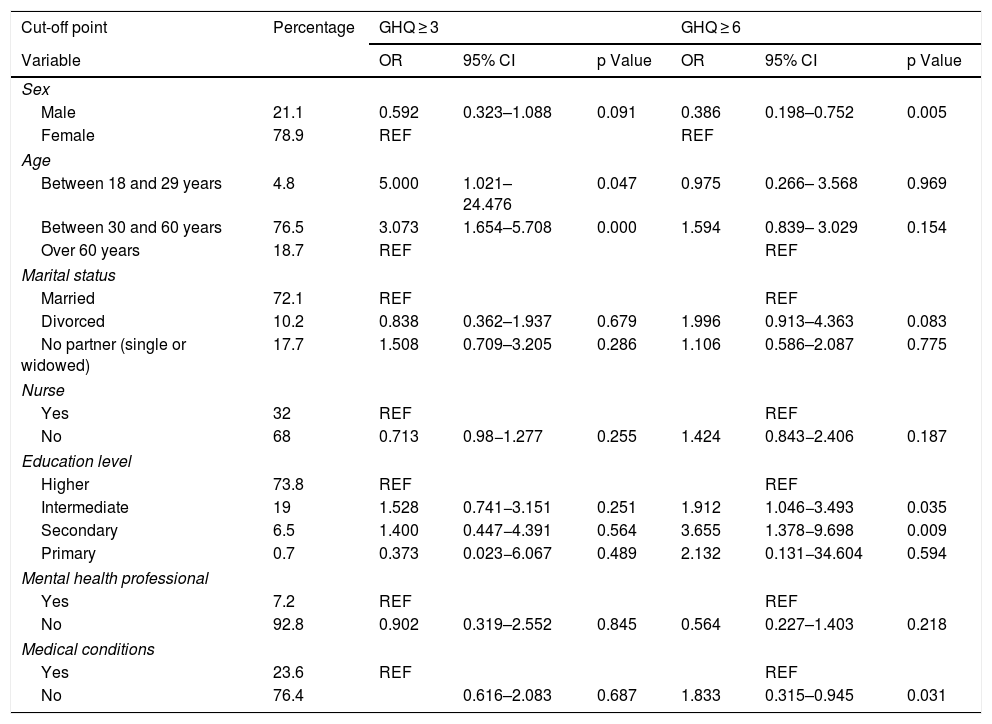

The results show that 74.9% of the participants have GHQ scores ≥ 3. The main characteristics of the sample can be seen in Table 1. The most commonly reported symptoms were: feeling constantly overwhelmed or stressed (94.5%) and losing a lot of sleep due to worry (82.6%). The following risk factors were identified: being a young professional, not always or not almost always complying with social distancing measures (OR: 2,885; 95% CI: 1,257−14,238; p = 0.020) and not complying with strict lockdown (OR: 2.885; 95% CI: 1.174–7.085; p = 0.021). However, the use of gloves, hand washing, and the use of a face mask were not found to be associated. With regard to factors associated with GHQ ≥ 6 scores and thus with having more symptoms, a higher proportion of females than males and of individuals with medical conditions at risk for COVID-19 have them. Also, those with intermediate or secondary education. The rest of the factors were not significantly associated (Table 1).

Binary logistic regression models on mental health.

| Cut-off point | Percentage | GHQ ≥ 3 | GHQ ≥ 6 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 21.1 | 0.592 | 0.323–1.088 | 0.091 | 0.386 | 0.198–0.752 | 0.005 |

| Female | 78.9 | REF | REF | ||||

| Age | |||||||

| Between 18 and 29 years | 4.8 | 5.000 | 1.021–24.476 | 0.047 | 0.975 | 0.266– 3.568 | 0.969 |

| Between 30 and 60 years | 76.5 | 3.073 | 1.654–5.708 | 0.000 | 1.594 | 0.839– 3.029 | 0.154 |

| Over 60 years | 18.7 | REF | REF | ||||

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married | 72.1 | REF | REF | ||||

| Divorced | 10.2 | 0.838 | 0.362–1.937 | 0.679 | 1.996 | 0.913–4.363 | 0.083 |

| No partner (single or widowed) | 17.7 | 1.508 | 0.709–3.205 | 0.286 | 1.106 | 0.586–2.087 | 0.775 |

| Nurse | |||||||

| Yes | 32 | REF | REF | ||||

| No | 68 | 0.713 | 0.98−1.277 | 0.255 | 1.424 | 0.843−2.406 | 0.187 |

| Education level | |||||||

| Higher | 73.8 | REF | REF | ||||

| Intermediate | 19 | 1.528 | 0.741−3.151 | 0.251 | 1.912 | 1.046−3.493 | 0.035 |

| Secondary | 6.5 | 1.400 | 0.447−4.391 | 0.564 | 3.655 | 1.378−9.698 | 0.009 |

| Primary | 0.7 | 0.373 | 0.023−6.067 | 0.489 | 2.132 | 0.131−34.604 | 0.594 |

| Mental health professional | |||||||

| Yes | 7.2 | REF | REF | ||||

| No | 92.8 | 0.902 | 0.319–2.552 | 0.845 | 0.564 | 0.227–1.403 | 0.218 |

| Medical conditions | |||||||

| Yes | 23.6 | REF | REF | ||||

| No | 76.4 | 0.616–2.083 | 0.687 | 1.833 | 0.315–0.945 | 0.031 | |

GHQ: General Health Questionnaire; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; REF: reference category.

To know if psychological capital acts as a protective factor, a binary logistic regression model was used, dividing the subjects into those with GHQ scores ≥ 3 and those with lower scores. The results show that the factors of resilience (B = −0.226; p = 0.002) and optimism (B = −0.282; p = 0.003) are negatively and significantly associated, while self-efficacy is not significantly associated (B = 0.038; p = 0.660). Hope, on the other hand, is positively associated (B = 40.411; p = 0.003). The Hosmer–Lemeshow statistic does not show evidence of a lack of fit of the model (χ2 = 11.585; gl = 8; p = 0.77).

The prevalence of mental health problems in the sample was 74.9%, a high prevalence and higher than that reported in studies prior to the onset of the pandemic, conducted both in Spain4 and abroad.5 The risk factors identified were: being a young professional and not always or not almost always complying with social distancing and lockdown measures. Resilience and optimism factors were also associated with a lower likelihood of developing mental health problems, so strengthening them could be of interest.

In conclusion, the results of this work clearly point to the importance of looking after the mental health of healthcare workers, especially younger professionals, and those whose work prevents them from complying with social distance measures and strict lockdown. Psychological capital and specifically, resilience and optimism factors worked as protective factors, so their enhancement could be of interest.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez-Jiménez M, Guerrero-Barona E, García-Gómez A. Salud mental y capital psicológico en profesionales sanitarios españoles durante la pandemia de COVID-19. Med Clin (Barc). 2021;156:357–358.