Introducción: La adolescencia es un periodo crítico para el desarrollo de la autoestima y la independencia, así como para consolidar patrones de comportamiento que sean de beneficio para la salud, al adquirir patrones de riesgo bajos o que sean protectores.

Objetivo: El propósito de este estudio es determinar la incidencia de comportamientos de riesgo, en una población de adolescentes con enfermedades crónicas, tratada en nuestras clínicas de especialidades comparados con una población sana con características demográficas similares.

Material y métodos: Diseñamos y validamos un cuestionario que fue aplicado a los pacientes de las diferentes clínicas de especialidades de nuestro Hospital (Reumatología, Nefrología, Oncología, Hematología y Endocrinología). El mismo instrumento fue aplicado a un grupo de control compuesto de estudiantes sanos de una escuela pública. Los cuestionarios fueron aplicados durante el periodo de enero a septiembre del 2010.

Resultados: Cien cuestionarios fueron aplicados a cada grupo, que tenía características demográficas similares. De todas las conductas de riesgo investigadas, una diferencia estadísticamente significante se reportó en el grupo de control en cuanto al consumo de alcohol (p<0.0001), consumo de cocaína (p=0.0037) y actividad sexual (p=0.0012), comparada con el grupo que padece alguna enfermedad crónica.

Conclusiones: Los pacientes con enfermedades crónicas participan de forma igual de los comportamientos de riesgo a su salud, al igual que la población sana. Por lo tanto, deben de ser incluidos en los programas de prevención y educación, al igual que la población sana.

Introduction: Adolescence is a critical period for developing self-esteem, and independence, and for consolidating behavior patterns that are beneficial to health by acquiring protective and/or low risk behaviors.

Objective: the aim of this study was to determine the incidence of risky behaviors in a population of adolescents with chronic disease treated at our specialty services, compared with a healthy population with similar demographic characteristics.

Material and methods: We designed and validated a questionnaire, which was applied to patients from different specialty clinics of our hospital (rheumatology, nephrology, oncology, hematology and endocrinology). the same instrument was applied to a control group of healthy students from a public school. the questionnaires were applied during the period of January to September, 2010.

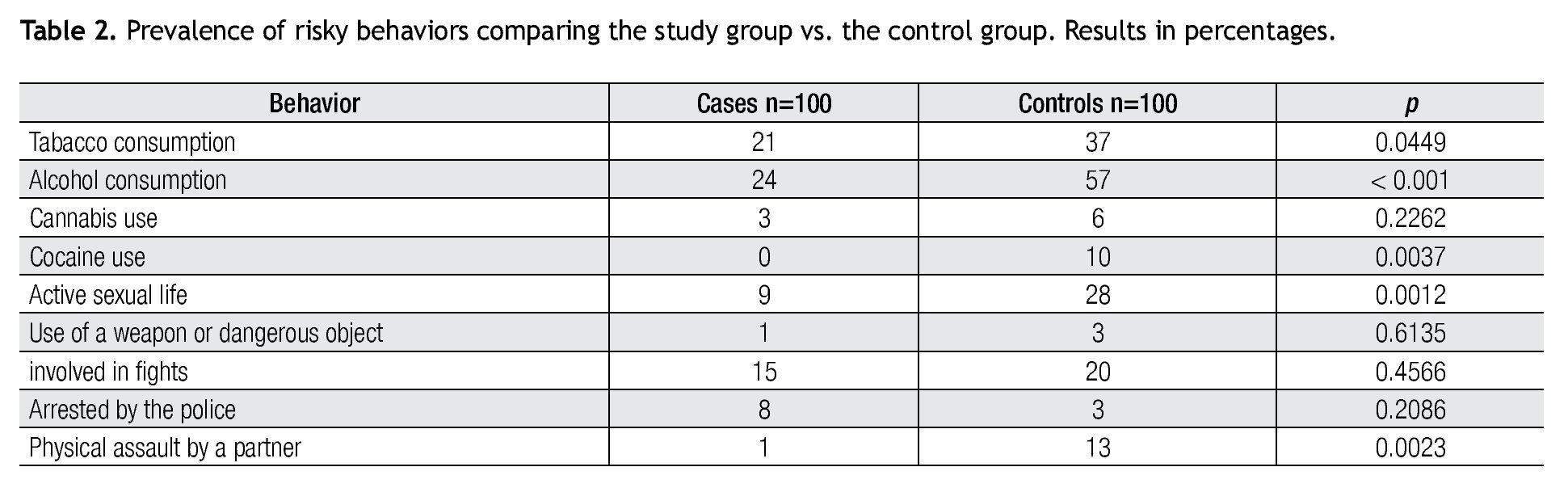

Results: One hundred questionnaires were applied to each group, which were of similar demographic characteristics. Of all the risky behaviors investigated, a statistically significant difference was reported in the control group in alcohol consumption (p<0.0001), cocaine use (p=0.0037) and sexual activity (p=0.0012) compared with the group suffering chronic disease.

Conclusions: Patients with chronic diseases participate equally in risky behaviors to their health as does the healthy population; therefore, they must be included in prevention and education programs the same as healthy population.

Pagina nueva 1

Introduction

Adolescence is a critical period for the development of self-esteem, independence, and building significant health patterns in the short, medium and long term, whether these are protective behaviors such as regular exercise, adequate standards of hygiene and food, or risky behaviors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, substance abuse, violent and antisocial behaviors, and early onset of sexual activity without protection. the social implications of these behaviors includes being able to use them as a way to gain respect and acceptance from peers, establishing independence from parents, or providing a subjective feeling of maturity and adequate stress management.1,2

The presence of a chronic disease imposes unique challenges to affected adolescents and their families, who ultimately require special care at home or frequent hospitalization depending on the severity of the disease, with the possibility of causing not only a physical or psychological impact in adolescents, but also in their relationships with family and peers.3

Although there are many studies investigating the emotional well-being of adolescents with an illness and risky behaviors, the reported results are still controversial and it is known that many of these reports have the disadvantage of focusing on a single set of conditions, or they otherwise investigate these behaviors in very large populations, where self-reported illnesses are used to define a chronic disease, knowing that what they can define as chronic can vary from asthma to migraine or another less well defined illness. It is also known that these diseases do not have the same impact on the lifestyle of the adolescent who suffers renal, hematologic-oncologic or rheumatologic problems.4-6

The aim of this study was to compare risky behaviors in adolescents with chronic diseases in rheumatology, such as lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis, and different types of leukemia, solid tumors, hemophilia and other hematologic-oncologic problems, and kidney disease, such as nephrotic syndrome/nephritis and chronic renal failure, and endocrinopathies such as type 1 diabetes mellitus, and hypo-and hyperthyroidism. the control group comprised socially similar healthy adolescents.

Material and methods

A 39-item instrument was designed, of which 13 were directed at the group with chronic disease asking about their daily activities, the effect of disease, and its emotional impact. the remaining 26 questions were divided into three areas: a) smoking, alcohol and other drug use, b) sexual activity, and c) violent behavior. it was based on a brief version of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS 2009)7 consisting of 83 items. Our version was validated in a population of 30 young volunteers without chronic disease where a correlation of 0.9 was found between the risk scores explored; no difference was found between the proportions of subjects who reported risk behaviors in both surveys (p<0.001).

The study was approved by the ethics and Human Research Committee of the School of Medicine and "Dr. José Eleuterio González" University Hospital of the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. Parents gave informed consent and subjects tested granted informed assent for inclusion in the study. the surveys were applied to patients in the endocrinology, rheumatology, nephrology and hematology-oncology clinics, with at least three months since diagnosis of their disease and in treatment during the period from January to September 2010. the control group was obtained by applying the same questionnaire to 100 adolescents in a secondary school from a low to middle socioeconomic area, comparable with the population attending this hospital. The confidentiality of the data and the anonymity of the participants in the survey were respected.

Continuous data are presented as means ± standard deviation, categorical data are presented as proportions, and for comparison of proportions we used Fisher's exact test or Chi square as appropriate.

Results

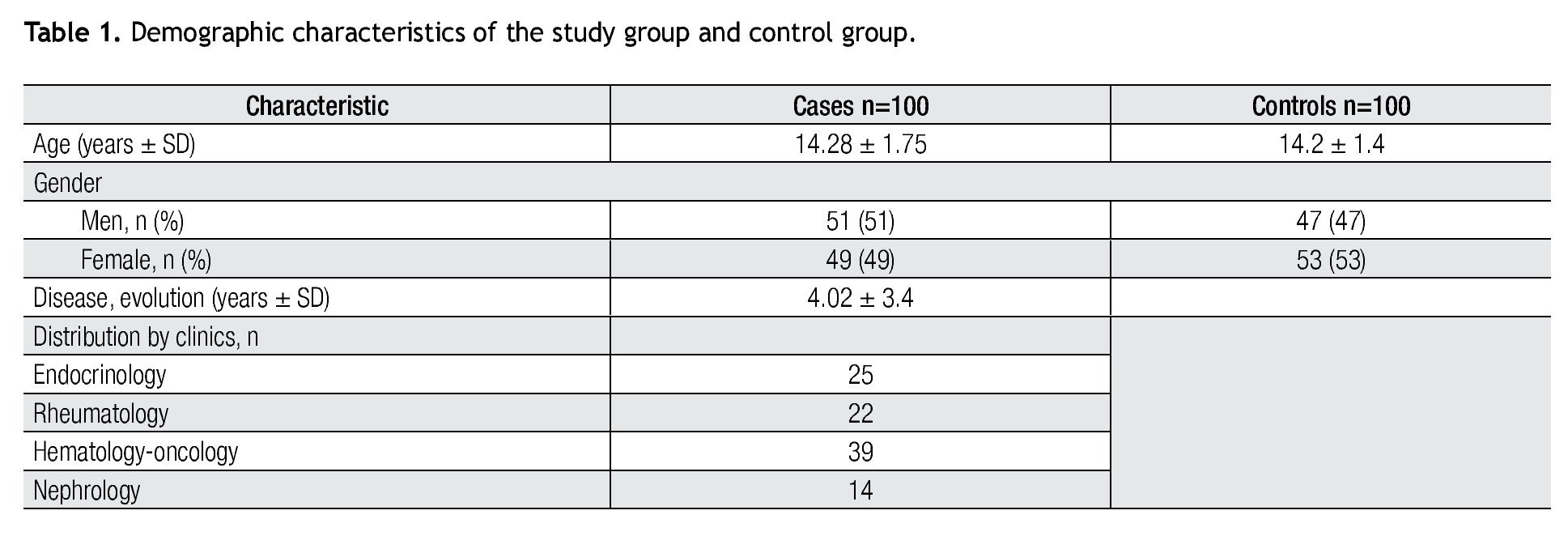

One hundred patients were surveyed in the endocrinology, Nephrology, Rheumatology and Hematology-Oncology clinics. Demographic data are summarized in Table 1. the distribution was 51 male and 49 female, with a mean age of 14.28 ± 1.75 years. Patients had an average of 4.02 ± 3.4 years of evolution with their disease, with a minimum of three months and a maximum of 16 years. We also surveyed a population of 100 healthy adolescents as the control group that comprised 47 male and 53 female with a mean age of 14.2 ± 1.4 years.

The use of tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs was reported by 21 patients (12 male, nine female) who said they had tried cigarettes at some time with a mean age of onset of 13.48 ± 1.28 years, reporting an average consumption of one to three cigarettes per day with a mean of 1.33 ± 0.65. in the control group, 37 subjects (21 male, 16 female) reported smoking (p=0.0449), with a mean age of onset of 13.27 ± 0.962 years with a daily average of 1.7 ± 1.1 cigarettes.

In relation to alcohol consumption, 24 patients (16 male, eight female) reported having tried alcohol, and 57 in the control group (28 male, 29 female), with a statistical significance (p<0.0001). Of the cases, 22 subjects reported occasional use (once a month or less) and only two subjects reported drinking every weekend. in the control group, 33 subjects consumed alcohol once a month or less, and 24 did it every weekend. two referred getting drunk, while 18 of the controls also got drunk.

Regarding the use of cannabis and other illicit drugs three patients had used cannabis at some time; two of these cases were female. All had used it one to five times in their lives, with an average age of onset of 14.3 years. In the control group six subjects (five male, one female) had used cannabis, five had used it one to five times in their lives and one 10 to 20 times, with a p=0.2262. the average age of onset of this group was 13.6 years. the study group did not report the use of cocaine, heroin, amphetamines, or solvents. in the control group there were 10 subjects who used cocaine (p=0.0037), three were female; two female subjects used solvents.

In the area of sexual activity, there were nine patients reporting sexual activity (three male and six female), compared with 28 controls (13 male and 15 female) (p=0.0012). the average age of initiating sexual activity in the cases was 14.44 ± 1.01 years and in controls was 14.7 ± 0.833 years. Of the sexually active patients, five reported having more than one sex partner, while 12 controls reported the same. Of these cases, nine reported using a condom as a method of family planning. in the control group, 19 used condoms, nine male and 10 female; one male did not know, and the rest did not use any birth control method.

As for violent behavior, regarding the question of whether they carried a weapon or a dangerous object for this purpose, one male of the cases and three male from the controls responded affirmatively; no female reported using a weapon. Regarding getting involved in a fight in the last year, 15 patients (seven male, eight female) answered affirmatively, in comparison to 20 controls (nine male, 11 female). When questioned if they had ever been arrested by the police, eight cases (four male and four female) answered affirmatively. Only three of the controls had been arrested, all female. One of the females reported physical assault by an intimate partner at some time, against 13 controls who reported the same (six male and seven female).

None of the respondents in either group reported being forced to have sex.

We summarize the prevalence of risky behaviors comparing the study group versus the control group in Table 2.

Discussion

In our study, both groups of adolescents did not differ significantly in age and gender. The adolescents who participated in our study had largely severe chronic diseases, requiring frequent monitoring by specialists and long-term treatment, which may have influenced our results. traditionally it has been thought that chronic illness is a protective factor for youth and that this condition prevented participation in risky behaviors. two previous studies by Suris et al.5,6 reported a high incidence of risky behaviors in sick adolescent population, but their studies were limited because they were carried out in schools, which probably eliminated the patient population whose daily activities are most affected by disease. this contrasts with our study group where an absenteeism of 60% was reported at least once a month because of illness.

Our study group reported low consumption of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs as well as low levels of early sexual activity. these results are similar to those reported by Carpentier et al in 20081 in 42 adolescent patients treated for cancer, which shows that this behavior may be due to increased supervision-protection by parents, a decrease in social interaction of these adolescents, and greater contact with health services.

Another study published in 2000 by Verrill, Schafer, Vannatta and Noll,8 in which questionnaires were used to compare involvement in antisocial behaviors and substance abuse among adolescent cancer survivors and a control group, also reported less involvement of adolescents with a disease, compared to healthy controls in all evaluated risk behaviors. A statistically significant difference was found only with use of illegal substances, concluding that a protective factor for violent or antisocial behavior exists with the disease, again suggesting that the greater involvement of parents and less unsupervised time with their peers can exert this protective effect, even if they overcome the disease, a fact that is comparable to the results obtained in our study.

By specifically evaluating each risk factor studied, the population that has tried alcohol, tobacco, cannabis and other drugs is greater in absolute numbers in the control group than in the study group, finding a significant difference in alcohol and cocaine use, with a tendency for increased consumption in the control group.

For sexually active population, we found a significant difference between both groups, with a greater frequency among controls. in both groups, mostly female responded affirmatively. In our patients, there was a low incidence of sexual activity contrary to what has been reported in the literature. Suris4 reported greater emotional distress among female adolescents with a chronic illness compared with male reporting symptoms of depression, sadness or emotional problems, which relates to a tendency to risky sexual behaviors, such as early onset of sexual activity and a greater number of partners. in a review by Valencia and Cromer in 200010 regarding sexual activity, they reported the same age of onset of sexual activity, and frequency and use of contraceptive methods, even those in which their illness affects their physical appearance; therefore it can be concluded that these patients are far from being asexual as many think, and they require care and education regarding safe sex practices and sexually transmitted diseases, but in our population this trend was not seen, in addition, all cases reported condom use. it could be because they are in greater contact with health personnel, and therefore receive professional information, although this is only speculative.

The review by Valencia and Cromer10 refers to studies that reported less involvement in antisocial behaviors such as gangs, weapons use or robbery in adolescents with chronic diseases. There were no significant differences in this area between our groups. What is relevant is the finding of involvement in police arrests, with this being reported more by cases, with no difference between gender, and with physical assault by an intimate partner having a higher incidence among controls with a similar distribution between male and female, but, like the rest of our results, without a statistically significant difference. Some authors attribute the involvement in antisocial behaviors of adolescent patients to the idea of living fast or maximally, with less fear of consequences due to their state of vulnerability, although it is generally accepted that adolescents, given their concrete thinking, consider less the risks in general, which is probably the only interpretation.

We cannot ignore the possibility that younger patients report fewer risky behaviors in order to hide them so that their parents and physicians do not find out; the survey method is weak in this regard, although it was conducted anonymously and confidentially, there is a possibility of bias in our study.

Conclusion

In our study, adolescents with chronic illness do not have a higher incidence of risky behaviors in in comparison with a control group; a tendency for less participation can be established.

Although we can interpret and take into account in prevention programs the possible protective factors against these risks, such as increased contact with health services and greater parental supervision, we still must be alert because adolescent patients are exposed to risk factors by engaging in these activities and the consequences to their health can be much greater, therefore we should work the same or more on prevention in this population.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Financial Support

There was no financial support involved in relation to this article.

Corresponding author:

Diana Laura Villarreal Rodríguez, MD.

Department of Pediatrics,

Hospital Universitario Dr. "José Eleuterio González",

Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León.

Av. Madero Poniente y Av. Gonzalitos s/n,

Colonia Mitras Centro, Z.P.

64460, Monterrey, N.L., Mexico.

Phone: +52 (81) 8348 5421, +52 (81) 8346 9959. Fax: +52 (81) 8348 9865.

E-mail: dilau00@hotmail.com

Received: September 2012.

Accepted: December 2012