Gender dysphoria, gender identity disorder or transsexualism is a psychological condition that requires care and multiple health professionals; endocrinologists, surgeons and psychiatrists are just some of the professionals needed to address these situations. The following article is a summary of what transsexuality means, its history and treatment, as more and more people request our services with a therapeutic approach.

Gender identity defines the extent to which each person identifies themselves as male, female or a combination of the two. It is the internal reference, built over time, which allows individuals to organize a sense of self and behave socially according to the perception of their own sex and gender. Gender identity determines the way people experience their gender and contributes to their sense of identity, singularity and of belonging.1

Gender identity disorder is defined as the inconsistency between physical phenotype and gender. In other words, self-identification as a man or a woman. Experiencing this inconsistency is known as gender dysphoria. The most extreme form, where people adapt their phenotype to make it consistent with their gender identity, through the use of hormones and by undergoing surgery, is called transsexualism. Individuals who experience this condition are referred to as trans, that is trans men (woman to man) and trans women (man to woman).2,3

Stoller4 established, in Sex and Gender Vol.1, the distinction between anatomical and physiological sex, being a man or woman and gender identity that masculinity and femininity combine in an individual. He defined transsexualism as “the conviction of a biologically normal subject of belonging to the opposite sex”. In an adult, nowadays this belief comes with a demand for endocrinological surgery in order to modify their anatomical appearance to that of the opposite sex.4 Becerra5 also expresses this idea in his definition of transsexualism. He points out that there is a conviction of transsexuals to belong to the opposite sex, with a constant dissatisfaction of their own primary and secondary sexual characters, with a deep sense of rejection and an expressed desire to surgically change them.5

In general, they refer to transsexuals as women who feel “trapped” in a man's body, and vice versa. Regarding diagnostic classifications, starting with the Feighner et al. criteria, they consider that one of the five necessary criteria to make a transsexualism diagnosis is the strong desire to physically resemble the opposite sex through any available means: for example, how to dress, conduct patterns, hormone therapy and surgery.6

Transsexuals present a sexual orientation within the same range of possibilities as heterosexuals, in other words, by the same sex or the opposite sex, both or neither. Another classification of transsexualism is the one proposed by Gooren,7 Herman-Jeglinska8 and Landén9 who make a distinction between early or primary and late or secondary. They explain that within early or primary transsexualism an inconformity is noticeable from an early age, effeminate or masculine behavior during their childhood, aversion for their bodies, a sense of belonging to the opposite sex, no fluctuations in gender dysphoria and same-sex sexual attraction. On the other hand, late or secondary transsexuals detect their condition approximately after 35 years of age, throughout their lives they have had transvestic episodes, and there is a high probability for them to feel regretful after their gender reassignment surgery, their sexual orientation fluctuates from heterosexuals to bisexuals, occasional homosexuals and homosexuals.7–9

HistoryTranssexualism is not a new phenomenon. It has existed for many years and in different cultures. In 1869, Westphal described a phenomenon he called “conträre sexual empfinding” which included some aspects of transsexualism. Later, in 1916, Marcuse described a type of psychosexual inversion which led toward sex change. In 1931, Abraham referred to the first patient who had an anatomic sex change performed. In 1894, Krafft-Ebing described a way of dressing according to the opposite sex, which he called “paranoid sexual metamorphosis”. In 1966, Harry Benjamin made the term “transsexual” popular, and in 1969, John Money coined the concept “Gender Reassignment”, with the intention of including different states where the basic characteristic is an alteration of sexual identity and gender. Money suggested the concept of gendermaps or gender schemes which encompass masculinity, femininity and androgenic codes in the brain. These maps would be established early in life and would be highly influenced by hormones during pregnancy. Finally, in 1989, Ray Blanchard suggested the term “autogynephilia” as the propensity to be sexually active thinking of oneself (a man) as a woman. This definition suggests, from a psychopathological perspective, a possible alteration or deep psychological variation of the sense of identity, in body identification (genital) as well as mental identity (the idea of one's gender).10

American endocrinologist Harry Benjamin compiled observations about transsexualism and the results of medical interventions in his book “The transsexual phenomenon”.11 The term “gender dysphoria syndrome” was proposed in 1973, which includes transsexualism in addition to other gender identity disorders. Gender dysphoria is used to describe the resulting dissatisfaction of the conflict between gender identity and assigned sex. In 1980, transsexualism appeared as a diagnosis in the DSM III (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, third edition). In the following revision of this manual (DSM IV) in 1994, the term transsexualism was abandoned, being replaced by the term gender identity disorder (GID) to describe those subjects who show a strong identification to the opposite gender and a constant dissatisfaction with their anatomical sex. In the DSM-V, the term gender identity disorder has been replaced by the term gender dysphoria. The International Classification of Diseases, tenth edition (ICD 10) mentions five different forms of GID, using, once again, the term transsexualism to refer to one of these forms. In 1979 the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association (HBIGDA) was founded, approving guidelines which are reviewed periodically and work as guidance for GIDs. The last review was in 2001.

EpidemiologyStudies of the epidemiology of transsexualism are scarce or null in most countries.12,13 The best estimate of the prevalence of GID or transsexualism comes from Europe, with a prevalence of 1 in 30,000 men and 1 in 100,000 women. The majority of clinical centers report three to five male patients for every female patient.14

In Mexico there is limited epidemiological data on transsexualism. There is evidence, unsupported by scientific research, suggesting the possibility of an even higher prevalence: (1) sometimes previously unknown gender problem diagnoses are made when treating patients with anxiety, depression, bipolar affective disorder, conduct disorders, drug abuse, identity dissociative disorders, borderline personality disorders, diverse sexual disorders, and intersexual conditions; (2) it is possible that some male transvestites, cross-dressers, transgender, and male and female homosexuals, who do not show up for treatment, have some form of gender identity disorder; (3) the intensity of the gender identity disorder in some people varies; (4) gender variation among people with feminine bodies is usually comparatively invisible to society, especially professionals and scientists.

EtiologyThere are several biological proposals that attempt to explain gender dysphoria conditions and homosexuality, ranging from genetic levels and prenatal alterations, to high hormone levels and external factors like stress.15

In regard to cerebral differences, it has been known for some time now that some structures are different between men and women, thus special attention has been placed on these structures in people with gender dysphoria. Different studies have been conducted to observe the central bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, which is involved in sexual dimorphism functions, including aggressive conduct, sexual conduct, and the secretion of gonadotropins, which are also affected by gonadal steroids.2

In regards to the neuronal density of the central bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, Kruijver et al. (2000) found that men (heterosexual and homosexual) have twice as many neurons as women; trans M–W are in the women's neuronal numeric range and the opposite occurs with trans W–M who are similar to men.16 In other words, size, innervation type and neuron number agree with gender and not with genetic sex. Unfortunately, this difference manifests during early adulthood, which means that this nucleus cannot be used for early gender dysphoria diagnoses.17

Various authors conclude that the factors which affect gender during early development are prenatal hormones and the components that change these hormone levels. While an influence in genetic factors must be present, an influence by postnatal social factors has not been established. In mice, masculinization of the developing brain is due to estrogens formed by testosterone aromatization. In the sexual differentiation of human brains, direct effects of testosterone seem to be of great importance. A clear example of this is subjects with mutations in androgen receptors, estrogen receptors or aromatase.18

The period where the human hypothalamus’ structural sexual differentiation occurs is between 4 years of age and adulthood, much later than it is usually presumed. However, the end of sexual differentiation may be based on processes already programmed in the middle of pregnancy or during the neonatal period.17–20

People have tried to explain its etiology in different ways. For example, Sigmund Freud believed that gender identity problems were the results of conflicts experienced by children in the Oedipal triangle. These problems are fueled by real family developments as well as the child's fantasies. Everything that interferes with the love the child feels toward his/her parent of the opposite sex, and with his/her identification with the parent who shares the same sex also interferes with normal gender identity.14 Gender identity is an organizing nucleus of the personality.20

Rodriguez Lamarque reports the evaluation and treatment of 9 men and a girl with gender identity disorder and observes how the parents’ personality disorders positively affected their marital dysfunction. This, combined with their personality pathologies, was a determinant contribution (not the only one) in the genesis of their children's gender identity disorders.21

DiagnosisIn order to make a precise gender dysphoria diagnosis, we use the ICD 10 criteria, as well as the DSM-V criteria.

ICD-10 defines transsexualism as the desire to live and be accepted as a member of the opposite sex, which is usually accompanied by feelings of discomfort or disagreement with their own anatomic sex, as well as the desire to undergo surgical and/or hormone treatment so that their bodies match as much as possible with the preferred sex. In order to diagnose it, transsexual identity must have been present constantly for at least two years and not be a symptom of another mental disorder, like schizophrenia, or secondary to any intersexual, genetic or sexual chromosome anomalies.

On the other hand sexual identity disorder in childhood is defined as a disorder which manifests clinically for the first time during early childhood (always long before puberty) characterized by an intense and persistent discomfort due to the person's own sex, along with the desire (or insistence) of belonging to the opposite sex. There is a constant concern about the opposite sex's clothes and activities or a rejection toward the person's own sex. These disorders are believed to be relatively rare and should not be confused with a lack of accordance with the socially accepted sexual role, which is much more frequent. A diagnosis of sexual identity disorder during childhood requires a deep alteration in the normal sense of masculinity or femininity. Simple masculinization of habits in girls or effemination in boys is not enough. Diagnosis cannot be made when the individual has reached puberty.22

However, DSM V's diagnostic criteria are divided into gender dysphoria in children and gender dysphoria in teenagers and adults. Gender dysphoria in children is defined as a strong inconsistency between the sex one feels or expresses and the one assigned, with duration of at least six months, which manifest in at least six of the following characteristics:

- •

A strong desire to belong to the opposite sex or an insistence that he or she belongs to the opposite sex (or from an alternative sex different from the one assigned).

- •

In boys (assigned sex), a strong preference for transvestism, or for simulating feminine attire; in girls (assigned sex) a strong preference for dressing only in typically masculine clothes and a strong resistance to wearing typically feminine clothes.

- •

A strong and persistence preference to play the opposite sex's role or fantasies about belonging to the opposite sex.

- •

A strong preference for the toys, games and activities customarily used or practiced by the opposite sex.

- •

A strong preference for playmates of the opposite sex.

- •

In boys (assigned sex), a strong rejection to typically masculine toys, games and activities, as well as a strong avoidance to rough play; in girls (assigned sex), a strong rejection of toys, games and activities which are typically feminine.

- •

A strong discontent with the individual's own sexual anatomy.

- •

A strong desire to have the primary and secondary sexual characteristics corresponding to the sex the individual feels.

The problem is associated with a clinically significant discomfort or deterioration in social, school and/or other areas important to functioning.

In gender dysphoria in teenagers and adults there is also a strong inconsistency between the sex the individual feels and expresses and the one assigned, with a duration of at least six months, manifested by at least two of the following characteristics:

- •

A strong inconsistency between the sex the individual feels or expresses and his or her primary or secondary sexual characteristics (or in young teenagers, visible secondary sexual characteristics).

- •

A strong desire to detach from their own primary or secondary sexual characteristics, due to a strong inconsistency between the sex the individual feels or expresses (or in young teenagers, a desire to impede the development of the visible secondary sexual characteristics).

- •

A strong desire to possess primary and secondary sexual characteristics corresponding to the opposite sex.

- •

A strong desire to belong to the opposite sex (or an alternative sex different from the one assigned).

- •

A strong desire to be treated as an individual of the opposite sex (or an alternative sex different from the one assigned).

- •

A strong conviction that one possesses feelings and reactions typical of the opposite sex (or an alternative sex different from the one assigned).

The problem is also associated with a clinically significant discomfort or deterioration in social, work and/or other areas important to functioning.23

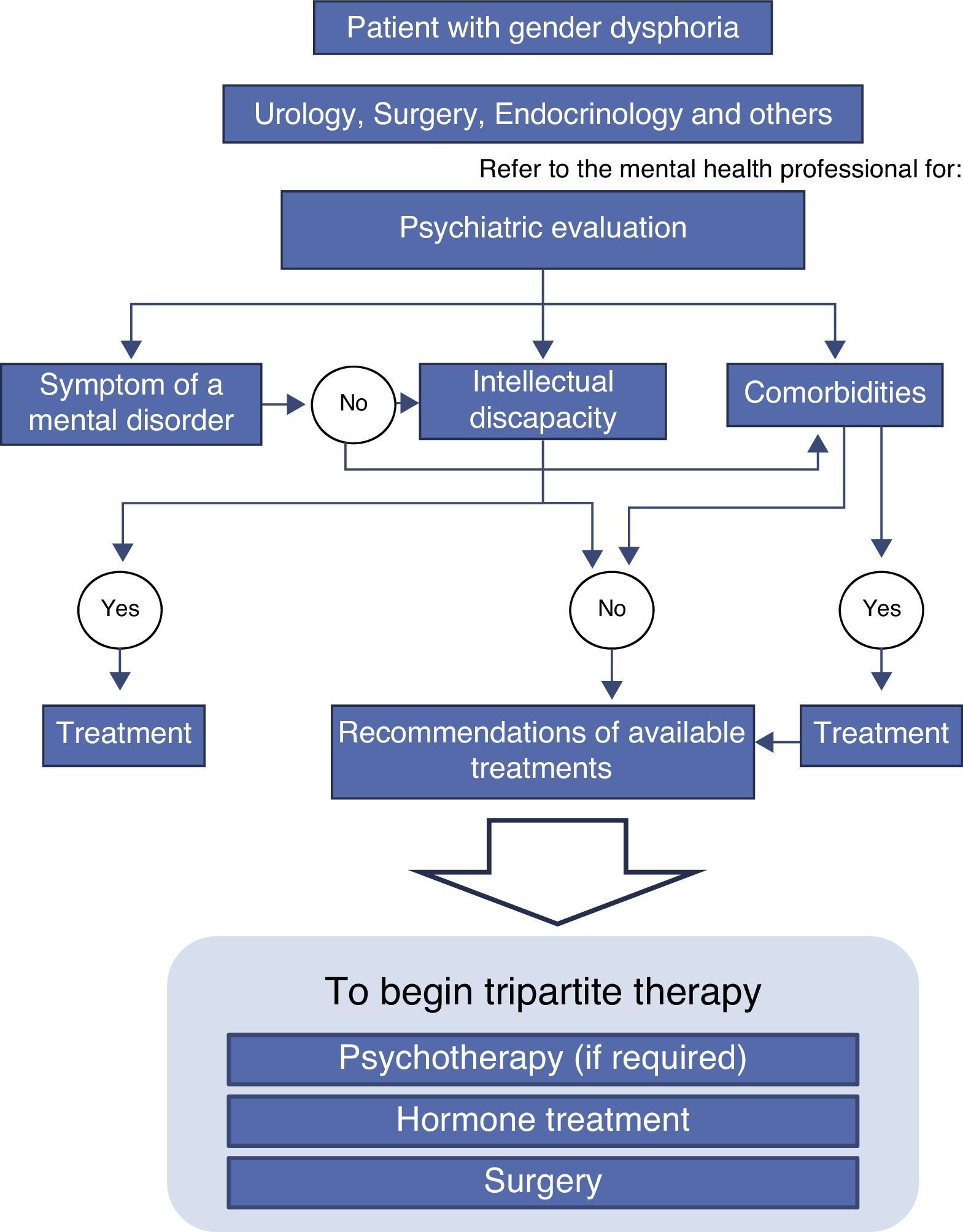

However, the psychiatric evaluation must include a comorbidity study in order to give a proper treatment, as described later.

TreatmentThe effectiveness of any pharmacological treatment to reduce the desire to change sexes has not been proven. When sexual dysphoria is severe and untreatable, sexual reassignment may be the best solution.24

Psychotherapy with the objective of “curing” transsexualism, in order to get the patient to accept oneself as a man or a woman, is useless with the currently available methods. The transsexual mind cannot be changed into a false gender orientation. Every attempt there that has been to do so has failed. The transsexual mind cannot adjust to the body, thus it is logical and justified doing the opposite and trying to adjust the body to the mind. Besides psychological orientation, this help has been given through two different therapeutic means: hormone medication and surgery.

A psychiatric evaluation must precede all gender reassignment surgical procedures, in order to establish not only the possible existence of psychosis, but also a reasonable degree of intelligence and emotional stability (Fig. 1).11

Nowadays the internationally accepted medical treatment protocols to treat these people includes sexual reassignment surgery, provided that the patient meets certain eligibility and disposition criteria. The most accepted protocol for the sex-reassignment process is based on the standards proposed during the eighties by the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association, which recommends a therapeutic triad (psychological, hormonal and surgical), determining specific eligibility criteria and additional forms obliging the fulfillment of therapeutic and surgical therapies.11–25 This association has changed names and is currently known as the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH).

After a GID diagnosis, the psychotherapist's focus generally includes three elements or stages (sometimes called triad therapy): a life experience in the desired role, hormones of the desired gender and a surgery to change genitals and other sexual features.

Mental health professionals who treat people with gender identity disorders are expected to undertake many of these responsibilities:

- •

Accurately diagnose the patient's gender identity disorder.

- •

Accurately diagnose any comorbid psychiatric conditions and perform appropriate treatment.

- •

Advise the patient regarding the available range of treatments and their consequences.

- •

Provide psychotherapy.

- •

Evaluate the patient's eligibility and suitability for hormone and surgical therapies.

- •

Make formal referrals to colleagues (doctors, surgeons, etc.)

- •

Describe the patient's relevant history in a referral certificate.

- •

Be part of a group of professionals interested in gender identity disorders.

- •

Educate relatives, employers and institutions about gender identity disorders.

- •

Make oneself available to the patients for follow-up treatments.26

In a study conducted in 2012 which studied clinical variables in gender identity disorders in 19 female transsexuals (FT man to woman) and 14 male transsexuals (MT woman to man) which created a demand for gender dysphoria public health services, they found that over half of the FT group had self-medicated hormones (52.6%), in contrast with the MT group, where no subject had initiated hormone treatment on their own. People who self-medicated hormones refer to getting or having gotten the hormone treatment on the streets. They would self-administer hormones without confirmation of a previous diagnosis and without timely medical supervision, usually through a trial-and-error approach depending on their affordability on the market. Similar situations have been found in other studies,27–29 reflecting the problems that these patients have in order to obtain hormone treatments in public hospitals in and out of Spain, consequently increasing the risk of complications.30 Despite the fact that there are no similar studies in Mexico, we should take the data into account given the risks that self-medication involves.

It is also interesting to point out the need for integral and integrated medical attention in the public health services for people with gender identity disorders. Being able to guarantee this type of therapy will be financed by public health,31 in addition to providing proper treatment, will end the agony transsexuals go through when searching illegally for the most diverse treatments, which endanger not only their mental health but their lives. This constant search for solutions has favored the marginality and stigmatization of transsexuals.26–31

GID patients must be treated by a multidisciplinary team: the psychiatrist or psychologist is the first one who usually sees them, and if the patient goes to see the endocrinologist, he/she should refer the patient to the psychiatrist/psychologist. These professionals share responsibilities in the decision to begin hormone and surgical treatment, along with the physician who prescribes them. Hormone treatment often alleviates anxiety and depression in patients without the need of recurring to additional medication. The existence of another psychopathology does not exclude surgery, but it may delay it.31

ConclusionsWhile gender dysphoria is a frequent diagnosis in our professional and social field, there is little research about the subject and there is a lack of precise information about the prevalence of this diagnosis in Mexico. In addition, there is a lack of guidelines to approach these patients. This situation causes the treatment to be performed in a partial manner, without taking into account that the proper approach includes at least a couple of health professionals who are in charge of guiding, informing and assessing the patient's physical and psychological condition.

It is our duty as health professionals to promote a multidisciplinary approach which allows gender dysphoria patients to improve their quality of life and decrease their present symptomatology.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.