Although antidepressants are widely used in Parkinson's disease (PD), few well-designed studies to support their efficacy have been conducted.

DevelopmentThese clinical guidelines are based on a review of the literature and the results of an AMN movement disorder study group survey.

ConclusionsEvidence suggests that nortriptyline, venlafaxine, paroxetine, and citalopram may be useful in treating depression in PD, although studies on paroxetine and citalopram yield conflicting results. In clinical practice, however, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are usually considered the treatment of choice. Duloxetine may be an alternative to venlafaxine, although the evidence for this is less, and venlafaxine plus mirtazapine may be useful in drug-resistant cases. Furthermore, citalopram may be indicated for the treatment of anxiety, atomoxetine for hypersomnia, trazodone and mirtazapine for insomnia and psychosis, and bupropion for apathy. In general, antidepressants are well tolerated in PD. However, clinicians should consider the anticholinergic effect of tricyclic antidepressants, the impact of serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors on blood pressure, the extrapyramidal effects of antidepressants, and any potential interactions between monoamine oxidase B inhibitors and other antidepressants.

El uso de antidepresivos está muy extendido en la enfermedad de Parkinson (EP), aunque existen pocos estudios de calidad que aclaren su eficacia.

DesarrolloLa metodología para esta guía clínica se ha basado en la revisión de la literatura y en la opinión de consenso del grupo de trastornos del movimiento de la AMN, recogida mediante una encuesta.

ConclusionesSegún la evidencia científica, nortriptilina, venlafaxina, paroxetina o citalopram podrían ser utilizados en el tratamiento de la depresión en la EP, aunque paroxetina y citalopram con resultados contradictorios. Sin embargo, en la práctica clínica, los inhibidores selectivos de la recaptación de serotonina suelen ser los fármacos de primera elección. Por otro lado, aunque con menor evidencia, duloxetina podría ser una alternativa a venlafaxina y la asociación de venlafaxina con mirtazapina podría ser útil en casos refractarios. Además, podemos considerar el uso de citalopram para la ansiedad, atomoxetina para el tratamiento de la hipersomnia diurna, trazodona y mirtazapina para el tratamiento del insomnio y la psicosis, y bupropión para el tratamiento de la apatía. En general, los antidepresivos son fármacos bien tolerados en la EP. No obstante, es necesario considerar el efecto anticolinérgico de los tricíclicos, el efecto sobre la presión arterial de los inhibidores de la recaptación de serotonina y noradrenalina, la capacidad de los antidepresivos para desarrollar síntomas extrapiramidales y tener precaución con la asociación de inhibidores de la monoaminooxidasa B.

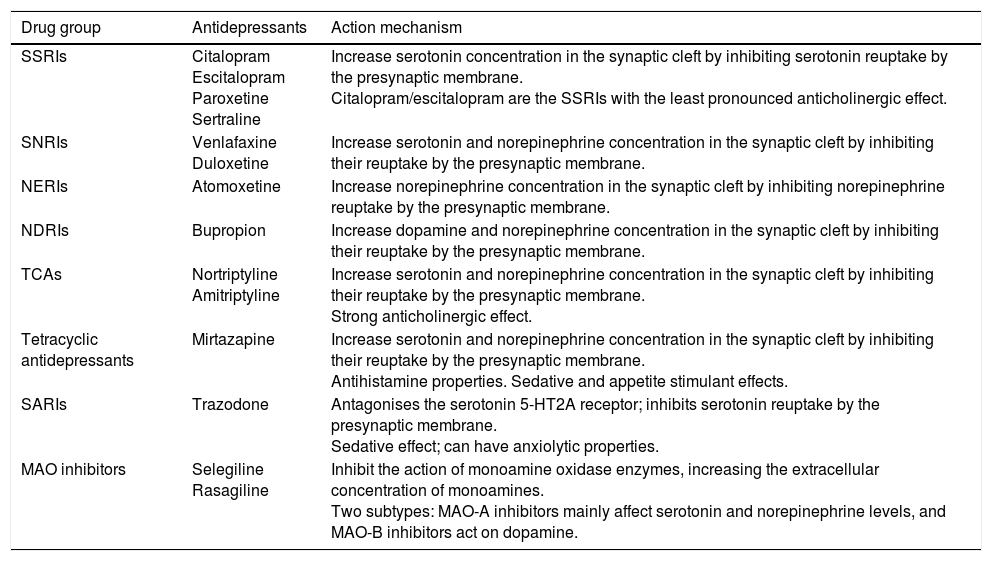

Antidepressants are a heterogeneous group of drugs whose action primarily consists in the stimulation of 3 neurotransmitter systems (the dopaminergic, serotonergic, and noradrenergic systems). These drugs are widely used by neurologists. In Parkinson's disease (PD), they are prescribed to treat depression, anxiety, and other non-motor symptoms. Table 1 lists the antidepressants that are most commonly used in daily practice and their main mechanisms of action.

A selection of antidepressants used in PD and their main mechanisms of action.

| Drug group | Antidepressants | Action mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| SSRIs | Citalopram Escitalopram Paroxetine Sertraline | Increase serotonin concentration in the synaptic cleft by inhibiting serotonin reuptake by the presynaptic membrane. Citalopram/escitalopram are the SSRIs with the least pronounced anticholinergic effect. |

| SNRIs | Venlafaxine Duloxetine | Increase serotonin and norepinephrine concentration in the synaptic cleft by inhibiting their reuptake by the presynaptic membrane. |

| NERIs | Atomoxetine | Increase norepinephrine concentration in the synaptic cleft by inhibiting norepinephrine reuptake by the presynaptic membrane. |

| NDRIs | Bupropion | Increase dopamine and norepinephrine concentration in the synaptic cleft by inhibiting their reuptake by the presynaptic membrane. |

| TCAs | Nortriptyline Amitriptyline | Increase serotonin and norepinephrine concentration in the synaptic cleft by inhibiting their reuptake by the presynaptic membrane. Strong anticholinergic effect. |

| Tetracyclic antidepressants | Mirtazapine | Increase serotonin and norepinephrine concentration in the synaptic cleft by inhibiting their reuptake by the presynaptic membrane. Antihistamine properties. Sedative and appetite stimulant effects. |

| SARIs | Trazodone | Antagonises the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor; inhibits serotonin reuptake by the presynaptic membrane. Sedative effect; can have anxiolytic properties. |

| MAO inhibitors | Selegiline Rasagiline | Inhibit the action of monoamine oxidase enzymes, increasing the extracellular concentration of monoamines. Two subtypes: MAO-A inhibitors mainly affect serotonin and norepinephrine levels, and MAO-B inhibitors act on dopamine. |

MAO: monoamine oxidase; NDRI: norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor; NERI: norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SARI: serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor; SNRI: serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA: tricyclic antidepressant.

Despite the high prevalence of non-motor symptoms in patients with PD (estimated at 3.6%-50% for anxiety1 and 13%-50.1% for depression2), and their significant impact on patients’ quality of life, they are often not adequately treated: it is estimated that only 20% of patients with PD presenting with anxiety or depression receive any type of medical or psychological treatment for these symptoms.3 The basis of the problem is the shortage of high-quality studies into the efficacy of antidepressants for different indications in patients with PD and the consequent lack of any clear recommendations; as a result, neurologists often have to rely on little more than their own experience when selecting a drug.

Considering the issues described above, the Neurological Association of Madrid's movement disorder study group deemed it beneficial to establish a series of general recommendations on the use of antidepressants in patients with PD. We hope that these recommendations, based on the available scientific evidence and our consensus opinion, may be of use to neurologists as a tool for decision-making in clinical practice.

DevelopmentMethodsWe performed a systematic search of the Medline database for published scientific articles, using the search terms “Parkinson's disease” and “antidepressants”, with special emphasis on papers published in the last 10 years. The bibliographical references of the articles found using this approach were used as an additional source of information. In addition to the literature review, 12 neurologists specialising in the field of movement disorders (members of our study group) were sent a survey on the use of antidepressants in daily clinical practice.

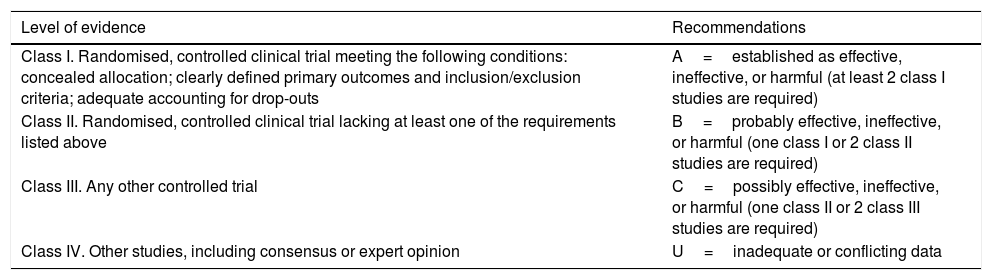

We used the levels of evidence and degrees of recommendation proposed by the American Academy of Neurology4–6 (Table 2) to assess the papers selected.

Levels of evidence and recommendations according the American Academy of Neurology classification.

| Level of evidence | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Class I. Randomised, controlled clinical trial meeting the following conditions: concealed allocation; clearly defined primary outcomes and inclusion/exclusion criteria; adequate accounting for drop-outs | A=established as effective, ineffective, or harmful (at least 2 class I studies are required) |

| Class II. Randomised, controlled clinical trial lacking at least one of the requirements listed above | B=probably effective, ineffective, or harmful (one class I or 2 class II studies are required) |

| Class III. Any other controlled trial | C=possibly effective, ineffective, or harmful (one class II or 2 class III studies are required) |

| Class IV. Other studies, including consensus or expert opinion | U=inadequate or conflicting data |

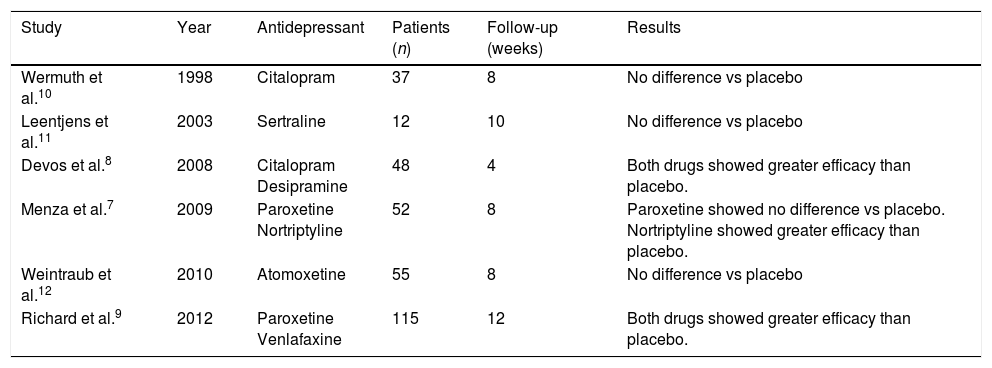

Few well-designed clinical trials have assessed the efficacy of antidepressants in treating depression in patients with PD; not all of these report positive results (Table 3). The only drugs that achieved statistically significant improvements in these trials were nortriptyline, desipramine, venlafaxine, paroxetine, and citalopram7–9; results were conflicting for the latter 2 drugs.7,10 Efficacy was not demonstrated for atomoxetine or sertraline.11,12 A 2011 meta-analysis concluded that tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) may be the most efficacious treatment for depression in patients with PD, followed by serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI); selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) were found to be the least efficacious.13 The Movement Disorder Society's14 recommendations for the treatment of non-motor symptoms of PD, also published in 2011, conclude that TCAs are probably efficacious for depression in patients with PD, but that there was not sufficient evidence supporting treatment with the remaining drug types. In fact, some reviews have recommended TCAs as the treatment of choice, at least in young patients without cognitive impairment.15 None of these recommendations take into account a later study by Richard et al.9 into paroxetine and venlafaxine, which found statistically significant improvements over placebo for both drugs. A recent meta-analysis which did include that study concluded that SSRIs specifically were associated with a significant improvement in depression in patients with PD, casting doubt over the efficacy of TCAs.16 This attests to the controversy surrounding the issue, which is far from being resolved.

Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trials on the efficacy of various antidepressants in treating depression in patients with PD.

| Study | Year | Antidepressant | Patients (n) | Follow-up (weeks) | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wermuth et al.10 | 1998 | Citalopram | 37 | 8 | No difference vs placebo |

| Leentjens et al.11 | 2003 | Sertraline | 12 | 10 | No difference vs placebo |

| Devos et al.8 | 2008 | Citalopram Desipramine | 48 | 4 | Both drugs showed greater efficacy than placebo. |

| Menza et al.7 | 2009 | Paroxetine Nortriptyline | 52 | 8 | Paroxetine showed no difference vs placebo. Nortriptyline showed greater efficacy than placebo. |

| Weintraub et al.12 | 2010 | Atomoxetine | 55 | 8 | No difference vs placebo |

| Richard et al.9 | 2012 | Paroxetine Venlafaxine | 115 | 12 | Both drugs showed greater efficacy than placebo. |

Other antidepressants may also be useful for treating depression in patients with PD, although there is less evidence supporting their use. A non-comparative longitudinal study into duloxetine demonstrated statistically significant improvements in patients’ scores on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, compared to baseline scores17; the drug may therefore represent an alternative to venlafaxine. Co-administration with mirtazapine has been shown to increase the efficacy of venlafaxine in treating depression.18 Although no study has evaluated this drug combination in patients with PD, it may also be taken into account when treating these patients, at least those with refractory depression. Finally, it would be valuable to assess the antidepressant properties of monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors, which are widely used to treat motor symptoms of PD. In a recent placebo-controlled clinical trial, 1mg rasagiline did not significantly improve symptoms of depression in patients with PD.19 However, a non-comparative longitudinal study found that 2mg rasagiline was associated with a significant improvement in depression compared to baseline, independently of the improvement in motor symptoms.20 Another non-comparative study found that depression significantly improved in patients with PD following administration of selegiline in combination with another antidepressant.21 These findings are of great interest given the current research into combination therapy with selegiline and other antidepressants to treat refractory depression.22 However, evidence on this subject is still very limited, and general recommendations cannot be made on the use of MAO-B inhibitors in this field. Finally, although they are not addressed in this review, it is worth noting the antidepressant effect of dopamine agonists, particularly pramipexole, as has been demonstrated in a class I study.23 Neurologists should consider using these drugs, perhaps even before administering specifically antidepressant drugs.2 Other treatments described include electroconvulsive therapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation, and psychotherapy.2

The effect of antidepressants on anxiety in patients with PD has only been evaluated by one non-comparative prospective study, and addressed as a secondary outcome measure in several other clinical trials.7–9,12,24 These studies found that only TCAs and citalopram achieved statistically significant improvements.7,8,24 Conversely, efficacy was not demonstrated in paroxetine, venlafaxine, or atomoxetine.9,12 Antidepressants may be indicated for other conditions in patients with PD. One study points to the potential efficacy of atomoxetine for treating daytime sleepiness.12 Further research is needed before recommendations can be made in this regard. Cases have also been described of mirtazapine achieving positive results in the treatment of psychosis in patients with PD.25–27 One comparative study of trazodone and haloperidol also reports the efficacy of trazodone in treating psychosis, although this study included patients with dementia, not PD.28 The sedative effect of these drugs may also make them effective as a treatment for insomnia.1 Finally, bupropion is thought to be useful in treating apathy associated to various neurodegenerative diseases, although evidence of this remains limited.29,30

Tolerability of antidepressants in patients with Parkinson's diseaseAntidepressants are generally well tolerated by patients with PD.13,14 However, TCAs should be used with caution in patients with urinary retention, closed-angle glaucoma, or cardiovascular diseases due to their anticholinergic effect.14 These drugs may also contribute to the development of psychosis, sedation, and daytime sleepiness in patients with PD, as well as cognitive dysfunction and delusion in cases where PD is associated with dementia.14 Arterial hypertension is a frequent side-effect of SNRIs; Richard et al.9 report hypertension in 4 of 34 patients receiving venlafaxine, compared to only one of 42 in the group of patients receiving paroxetine and no patients in the control group. SNRIs must therefore be used with caution in patients with poorly controlled hypertension or cardiovascular comorbidities.

Extrapyramidal adverse effects of antidepressantsAll classes of antidepressant, particularly SSRIs and SNRIs, have been associated with extrapyramidal adverse effects.31 These adverse reactions appear to be less frequent in TCAs.32 Previous treatment with neuroleptics, lithium, or oestrogens seems to favour onset of extrapyramidal adverse effects in patients receiving TCAs.32 Isolated cases have also been reported of bupropion-induced parkinsonism.33,34

A review of extrapyramidal symptoms in patients treated with serotonergic antidepressants, which included 86 articles published between 1998 and 2015 and a total of 91 patients, found greater incidence of these symptoms in patients younger than 65 years old (78%) and in women (57% vs 43% in men).31 In addition to this, 22% of patients were also receiving drugs with potential extrapyramidal effects, such as antipsychotics.31 The adverse reactions described include akathisia, dystonia, parkinsonism, and dyskinesia.31 At normal doses, symptoms generally appeared within the first 30 days of treatment; in 67% of cases, onset occurred during the first 7 days.31 The exception to this was dyskinesia, which was characterised by a more delayed onset (later than 30 days in 55.6% of patients and later than 90 in 44%).31 The drugs most frequently associated with this type of adverse effect were citalopram/escitalopram (22%), fluoxetine (20.9%), sertraline (15.4%), venlafaxine (12.1%), and duloxetine (5.5%).31 Of the 19 cases of antidepressant-associated onset or worsening of parkinsonism, 15 (79%) were due to SSRIs, 6 of which (40%) were associated with sertraline.31 Of the 4 cases of SNRI-associated parkinsonism, 2 were caused by venlafaxine and 2 by milnacipran; no cases were due to duloxetine use. Fifty-eight per cent of patients were older than 65 years old; slightly over half were women.31

A recent meta-analysis of patients with PD, including only randomised controlled trials, found few cases of adverse effects on motor function; these were isolated and showed no significant differences compared to placebo.16 One of the studies included, comparing citalopram and desipramine against placebo, reported that one of the 15 patients receiving citalopram experienced worsening of bradykinesia to the extent that treatment was suspended.8 In the same study, 2 patients receiving the placebo, one receiving citalopram, and one patient receiving desipramine, displayed mild, transient tremor.8 Another study reported that PD symptoms worsened in a patient treated with citalopram, although motor function was unaffected.10 Finally, clinical trials on sertraline,11 nortriptyline,7 venlafaxine,9 and paroxetine7,9 reported no significant extrapyramidal adverse effects. However, in the Richard et al.9 study, tremor was observed in 7 patients from the treatment group (16% of those treated with paroxetine and 20% of those treated with venlafaxine) and 3 from the placebo group. In fact, one of the patients receiving venlafaxine dropped out of the study due to this symptom.9 Finally, a study by Bonuccelli et al.17 found no worsening of motor symptoms in patients receiving duloxetine.

Two papers specifically evaluated the effect of antidepressant treatment on motor symptoms in patients with PD.35,36 Dell’Agnello et al.35 performed a prospective study into the incidence of extrapyramidal adverse effects of 4 SSRIs (citalopram, sertraline, fluvoxamine, and fluoxetine) in a group of 62 patients with PD presenting with stable motor symptoms. The patients were assessed with the UPDRS at baseline and at 1, 3, and 6 months after treatment onset. Patients received either 50mg/day sertraline, 20mg/day citalopram, 20mg/day fluoxetine, or 150mg/day fluvoxamine. No significant differences were observed in UPDRS scores. Two patients in the fluvoxamine group and 2 in the fluoxetine group displayed a worsening of tremor.

Kulisevsky et al.36 performed a 6-month prospective, naturalistic study, including 374 patients with PD associated with depression and undergoing treatment with sertraline (66±29.8mg/day). According to UPDRS scores, treatment had no significant adverse effects on motor symptoms; improvements were even observed. Three patients displayed worsening of tremor and 2 displayed new-onset tremor.

To summarise, though infrequent, extrapyramidal symptoms can be induced by antidepressants at normal doses and should be considered when prescribing these drugs. Although antidepressants do not generally have a significant negative effect on motor function in patients with PD, isolated cases may occur, with tremor being the most frequent symptom.

The issue of combining monoamine oxidase B inhibitors and other antidepressantsPrescribing MAO-B inhibitors in combination with other antidepressants is a controversial subject due to the risk of serotonin syndrome, which can be severe and potentially fatal. The summary of product characteristics for selegiline contraindicates its use in combination with other antidepressants. The summary of product characteristics for rasagiline contraindicates concomitant use of other MAO-B inhibitors, and recommends avoidance of fluoxetine and fluvoxamine and caution with all other antidepressants. Richard et al.37 performed a study on selegiline use in 4468 patients, establishing an incidence of 0.24% for serotonin syndrome, with severe episodes having an incidence of 0.04%. Nonetheless, other recent studies into the combination of rasagiline with SSRIs, SNRIs, TCAs, or other antidepressants, with a total of 978 patients, did not find any cases of serotonin syndrome,38 significant increases in unexpected adverse effects,39,40 or an increase in drop-out rates as a result of the combination of these drugs.40

Clinical practiceSeven of the 12 neurologists participating in our survey preferred SSRIs, particularly escitalopram, citalopram, sertraline, and paroxetine, as the drug of first choice to treat depression in patients with PD. This choice was justified by good tolerance, few drug–drug interactions, and suitability for patients with comorbidities. SNRIs, particularly duloxetine, were the antidepressants of choice for 4 participants; only 2 neurologists opted for TCAs, with amitriptyline being the most frequently used drug in this case. Efficacy was one of the motives given for this preference. However, there was a tendency to avoid prescribing SNRIs and TCAs to patients of advanced age or with associated cognitive impairment or other comorbidities; in these cases, SSRIs were preferred, and particularly those with a less pronounced anticholinergic effect. Finally, 2 neurologists selected other types of antidepressants as their first choice of drug, with mirtazapine receiving particular emphasis.

Ten participants selected SNRIs as the drug of second choice, particularly displaying a preference for duloxetine over venlafaxine. The other options selected were more diverse: TCAs, SSRIs, mirtazapine (either alone or in combination with other drugs), bupropion, and trazadone.

Nine respondents reported using antidepressants to treat other non-motor symptoms of PD. This also influenced drug choice. Frequently mentioned examples were bupropion for apathy, mirtazapine for insomnia and to stimulate appetite, trazodone for insomnia and mild psychosis, duloxetine for pain, and amitriptyline for sialorrhoea. Combination of an antidepressant with quetiapine or clozapine was also frequent for patients with depression associated with psychotic symptoms.

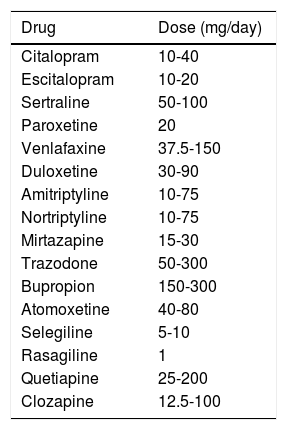

Regarding alternative treatments, 9 survey respondents mentioned the antidepressant effects of such other drugs as MAO-B inhibitors and pramipexole. Seven mentioned non-pharmacological treatments, including psychotherapy, occupational therapy, and physical exercise. Finally, 10 participants reported prescribing antidepressants to patients also receiving MAO-B inhibitors, observing no clinically significant adverse effects. The doses most frequently used in clinical practice are shown in Table 4.

Typical doses prescribed in clinical practice.

| Drug | Dose (mg/day) |

|---|---|

| Citalopram | 10-40 |

| Escitalopram | 10-20 |

| Sertraline | 50-100 |

| Paroxetine | 20 |

| Venlafaxine | 37.5-150 |

| Duloxetine | 30-90 |

| Amitriptyline | 10-75 |

| Nortriptyline | 10-75 |

| Mirtazapine | 15-30 |

| Trazodone | 50-300 |

| Bupropion | 150-300 |

| Atomoxetine | 40-80 |

| Selegiline | 5-10 |

| Rasagiline | 1 |

| Quetiapine | 25-200 |

| Clozapine | 12.5-100 |

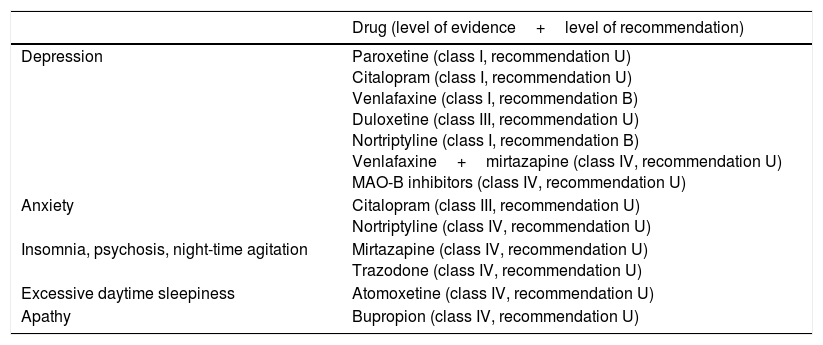

Based on the available scientific evidence, nortriptyline, venlafaxine, paroxetine, and citalopram may be used to treat depression in patients with PD, although conflicting results were found for the latter 2 drugs. In clinical practice, on the other hand, SSRIs are usually the drugs of first choice, as they are perceived as being well tolerated, having few drug–drug interactions, and being suitable for patients with comorbidities. Duloxetine may serve as an alternative to venlafaxine, and venlafaxine combined with mirtazapine may be useful in cases of refractory depression; the scientific evidence supporting this is more limited, however. Neurologists should also consider prescribing citalopram to treat anxiety; atomoxetine for excessive daytime sleepiness; trazodone and mirtazapine for insomnia, psychosis, and agitation; and bupropion for apathy. Table 5 shows the levels of evidence for different indications.

Levels of evidence and grades of recommendation of different antidepressants for different indications in patients with PD.

| Drug (level of evidence+level of recommendation) | |

|---|---|

| Depression | Paroxetine (class I, recommendation U) Citalopram (class I, recommendation U) Venlafaxine (class I, recommendation B) Duloxetine (class III, recommendation U) Nortriptyline (class I, recommendation B) Venlafaxine+mirtazapine (class IV, recommendation U) MAO-B inhibitors (class IV, recommendation U) |

| Anxiety | Citalopram (class III, recommendation U) Nortriptyline (class IV, recommendation U) |

| Insomnia, psychosis, night-time agitation | Mirtazapine (class IV, recommendation U) Trazodone (class IV, recommendation U) |

| Excessive daytime sleepiness | Atomoxetine (class IV, recommendation U) |

| Apathy | Bupropion (class IV, recommendation U) |

Antidepressants are generally well tolerated by patients with PD. Nonetheless, depending on each patient's clinical characteristics, we must take into account the anticholinergic effect of TCAs, SNRIs’ effect on blood pressure, and the potential for antidepressant use to lead to the appearance of extrapyramidal symptoms. The evidence available in the literature appears to indicate the safety of co-prescribing MAO-B inhibitors, particularly rasagiline, with other antidepressants. However, caution should be exercised given the severity of the potential adverse effects. The instructions in the summary of product characteristics should always be followed. Further study is needed in this field.

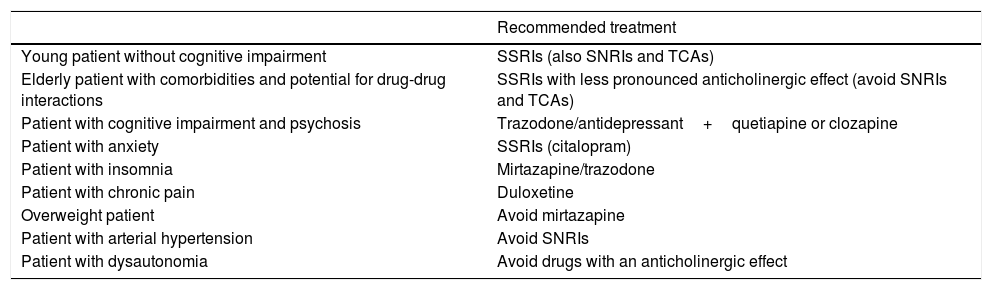

Given the lack of additional studies and the potential for adverse effects in patients with PD, the patient's clinical profile is of great importance in selecting an antidepressant. Based on the publications available in the literature and our own survey results, we have made a series of recommendations for the treatment of various common clinical situations, which we present in Table 6.

Recommendations for the pharmacological treatment of depression in patients with PD according to clinical profile.

| Recommended treatment | |

|---|---|

| Young patient without cognitive impairment | SSRIs (also SNRIs and TCAs) |

| Elderly patient with comorbidities and potential for drug-drug interactions | SSRIs with less pronounced anticholinergic effect (avoid SNRIs and TCAs) |

| Patient with cognitive impairment and psychosis | Trazodone/antidepressant+quetiapine or clozapine |

| Patient with anxiety | SSRIs (citalopram) |

| Patient with insomnia | Mirtazapine/trazodone |

| Patient with chronic pain | Duloxetine |

| Overweight patient | Avoid mirtazapine |

| Patient with arterial hypertension | Avoid SNRIs |

| Patient with dysautonomia | Avoid drugs with an anticholinergic effect |

In conclusion, further evidence is needed to clarify the role of antidepressant use in patients with PD, in treating both depression and such other conditions as anxiety, insomnia, hypersomnia, nocturnal psychosis, and apathy.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Peña E, Mata M, López-Manzanares L, Kurtis M, Eimil M, Martínez-Castrillo JC, et al. Antidepresivos en la enfermedad de Parkinson. Recomendaciones del grupo de trastornos del movimiento de la Asociación Madrileña de Neurología. Neurología. 2018;33:395–402.

On behalf of the movement disorder study group of the Neurological Association of Madrid.