Caffeine is the most widely used psychostimulant worldwide. Excessive caffeine consumption induces a series of both acute and chronic biological and physiological changes that may give rise to cognitive decline, depression, fatigue, insomnia, cardiovascular changes, and headache. Chronic consumption of caffeine promotes a pro-nociceptive state of cortical hyperexcitability that can intensify a primary headache or trigger a headache due to excessive analgesic use. This review offers an in-depth analysis of the physiological mechanisms of caffeine and its relationship with headache.

La cafeína es la droga psicoestimulante más ampliamente utilizada en el mundo. El exagerado consumo de cafeína induce una serie de cambios biológicos y fisiológicos de forma aguda y crónica, que se pueden traducir en déficit cognitivo, depresión, fatiga, insomnio, cambios cardiovasculares y cefalea. El consumo crónico de cafeína promueve un estado pronociceptivo y de hiperexcitabilidad cortical que puede exacerbar una cefalea primaria o desencadenar una cefalea por uso excesivo de analgésicos. El objetivo de la revisión es profundizar en los aspectos fisiológicos de la cafeína y su relación con la cefalea.

Caffeine is the world's most widely consumed psychostimulant drug. In the USA, over 87% of the population consumes some amount of caffeine every day.1 Caffeine intake in healthy adults is not recommended to exceed 400-450mg/day. In the USA, however, nearly 30% of the population consumes over 500mg/day, and this tendency is most frequently seen among people aged 35 to 64.2 Excessive caffeine consumption causes acute and long-term biological and physiological changes deriving in cognitive deficits, depression, fatigue, insomnia, cardiovascular problems, and headache, among others.3

At high doses, caffeine has an antinoceptive effect and acts as an adjuvant to other analgesics. In the long-term, however, excessive caffeine consumption may increase the risk of medication overuse headache and lead to chronification of some primary headaches. Caffeine may also cause physical dependence which may manifest as withdrawal syndrome.4 The International Headache Society does not list caffeine among substances potentially causing analgesic-overuse headache but rather as a substance that may cause headache when regular consumption over 200mg/day for more than 2 weeks is discontinued abruptly.5 The purpose of our review article is to gain a better understanding of the physiological effects of caffeine and its association with headache, whether as a trigger factor for medication overuse headache or as a substance exacerbating primary headache.

Caffeine: action mechanism and its association with the pathophysiology of headacheCaffeine, a chemical compound found in coffee, was isolated in 1819 by German chemist Friedrich Ferdinand Runge; this researcher coined the term ‘Kaffein’, which became ‘caffeine’ in English.6 Caffeine, also known as trimethylxanthine, is a naturally occurring alkaloid in some plants. It is synthesised from adenosine and metabolised by cytochrome P450 (CYP1A2) into different active metabolites: paraxanthine (84%), theobromine (12%), and theophylline (4%).6 Caffeine has an oral bioavailability of almost 100% and a half-life ranging from 4 to 9 hours, depending on several factors: it is shorter in smokers and longer in women who are pregnant or taking oral contraceptives.6

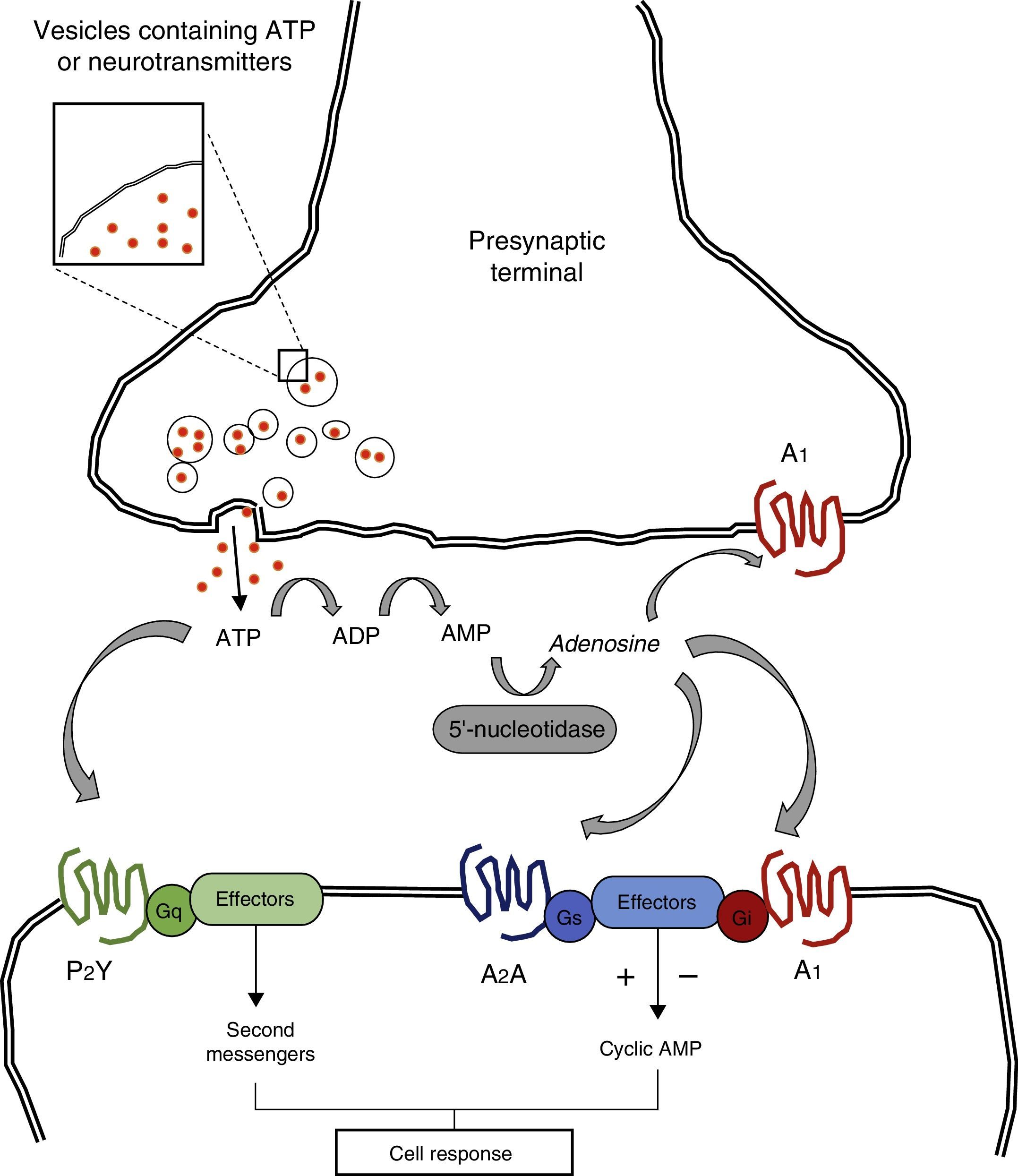

Caffeine molecules, which are structurally similar to adenosine, bind to adenosine receptors in the cell surface without activating them, thereby acting as competitive inhibitors.6 Adenosine is a purine nucleotide released by adenosine triphosphate (ATP) from astrocytes. It acts at the neuronal level thanks to the action of P1 receptors; these receptors are also known as adenosine receptors and they are G protein-coupled.7 Four subtypes of adenosine receptors have been described to date: A1, A2A, A2B, and A3. A1 receptors are the subtype of adenosine receptors with the widest distribution throughout the brain and spinal cord, and they also have the greatest affinity for caffeine (Fig. 1).7 In general terms, adenosine inhibits the release of excitatory neurotransmitters leading to decreased cortical excitability. Caffeine induces a state of cortical hyperexcitability due to its inhibitory effect on adenosine receptors; this process increases alertness and improves cognitive function.7

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is released into the synaptic cleft from presynaptic vesicles. ATP may interact directly with such postsynaptic receptors as P2Y and P2X, which are G protein-coupled. ATP may be transformed into adenosine by means of such enzymes as ectodiphosphohydrolase and 5′-nucleotidase. Adenosine interacts with G protein-coupled pre- and postsynaptic receptors, regulating adenylyl cyclase and the cyclic AMP pathway.

Adapted from Nestler et al.7

In this context, the hypothesis that caffeine has an analgesic effect and may be useful in acute management of headache may seem paradoxical. However, the analgesic action of caffeine is based on its powerful vasoconstrictor effect, which counteracts the vasodilator effect of purines.8 This is the basis for the ‘purinergic’ hypothesis for migraine, a theory proposed in 1989 which suggests that purines trigger migraine attacks due to their powerful vasodilator effect.9 Some studies have supported the purinergic hypothesis as an epiphenomenon rather than the factor triggering migraine. Guieu et al.10 observed elevated plasma levels of adenosine during migraine attacks whereas Brown et al.11 showed that administering exogenous adenosine precipitated migraine. Based on the above, it seems reasonable that caffeine would have an analgesic effect and be useful for acute management of headache. In addition to its powerful vasoconstrictor effect, caffeine may act as an analgesic given its ability to inhibit the synthesis of leukotrienes and prostaglandins, which are clearly involved in the pathophysiology of migraine.12

Some studies in animal models have shown that prostaglandin E2, when acting via EP4 receptors, promotes vasodilation of the middle cerebral and middle meningeal arteries, the main arteries involved in the vascular pathophysiology of migraine.13 Furthermore, other studies have shown that prostaglandin E2 promotes the release of calcitonin gene-related peptide, a multifunctional neuropeptide that regulates peripheral vascular tone and sensory transmission and has been directly associated with migraine pathophysiology.14 Thus, the effect of caffeine on prostaglandin synthesis induces an antinociceptive state.

The analgesic effect of caffeine is also favoured by its action as an adjuvant to other anaesthetics; caffeine promotes gastric absorption due to increased production of cyclic AMP.15 Some studies have shown that adding caffeine to an analgesic reduces the dose necessary to achieve the same effect by 40%.16

Caffeine is thus an analgesic whose mechanism relies on its powerful vasoconstriction effect and the ability to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis, and to promote the absorption of other analgesics. Despite these remarkable effects, long-term caffeine consumption in patients with migraine triggers a cascade of physiological changes that may deliver 3 different clinical situations: exacerbation of primary headache, caffeine-withdrawal headache, and analgesic-overuse headache.

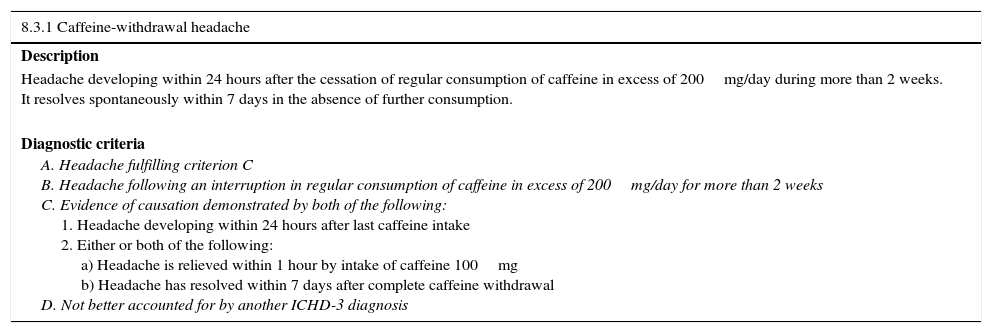

Caffeine in patients with headache: an aggravator of primary headache or a trigger of analgesic-overuse headache?The question of whether caffeine exacerbates primary headache or triggers analgesic-overuse headache is difficult to answer based on available evidence. On the pathophysiological level, long-term caffeine overuse (>450mg/day) causes a series of metabolic changes that may exacerbate primary headache and even trigger analgesic-overuse headache. Long-term effects of caffeine overuse result from over-regulation and hypersensitivity of adenosine receptors.17 This process may explain the marked physical dependence resulting from long-term caffeine overuse. It also serves as the basis for understanding withdrawal syndrome: when caffeine consumption is interrupted abruptly, adenosine receptors become available, leading to vasodilation and significant increases in cerebral blood flow.17 These physiological changes are responsible for caffeine-withdrawal headache; this entity is included in group 8 of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (Table 1).5 Pathophysiological evidence suggests that caffeine exacerbates primary headache and triggers analgesic-overuse headache.

Diagnostic criteria for caffeine-withdrawal headache.

| 8.3.1 Caffeine-withdrawal headache |

|---|

| Description |

| Headache developing within 24 hours after the cessation of regular consumption of caffeine in excess of 200mg/day during more than 2 weeks. It resolves spontaneously within 7 days in the absence of further consumption. |

| Diagnostic criteria A. Headache fulfilling criterion C B. Headache following an interruption in regular consumption of caffeine in excess of 200mg/day for more than 2 weeks C. Evidence of causation demonstrated by both of the following: 1. Headache developing within 24 hours after last caffeine intake 2. Either or both of the following: a) Headache is relieved within 1 hour by intake of caffeine 100mg b) Headache has resolved within 7 days after complete caffeine withdrawal D. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis |

Adapted from the International Classification of Headache Disorders (IHS).5

Analgesic-overuse headache is a cause of chronic headache presenting in genetically susceptible patients. This type of headache is promoted by the pharmacological properties of certain drugs and it alters central and peripheral mechanisms of pain modulation.18 It is characterised by 2 main pathophysiological mechanisms: cortical hyperexcitability and increased peripheral and central sensitisation.18 Both phenomena are chronic effects of excessive caffeine consumption: cortical hyperexcitability is induced by increased release of excitatory neurotransmitters (mainly glutamate),19 whereas a pro-nociceptive state is promoted by chronic activation of A2A receptors at the peripheral level. These receptors promote the effect of calcitonin gene-related peptide, a powerful pro-nociceptive neuropeptide that plays a major role in the chronification of some types of primary headache.20 In view of the clear pathophysiological correlation between analgesic-overuse headache and prolonged excessive caffeine consumption, we posit that caffeine is an analgesic capable of inducing structural and functional changes that manifest as analgesic-overuse headache.

Caffeine and primary headacheThere is pathophysiological evidence that the cortical hyperexcitability and pro-nociceptive state induced by long-term excessive caffeine consumption both exacerbate primary headache. Numerous clinical observations and analytical studies support this conclusion. For example, one study found migraine attacks to be more frequent on Saturday and Sunday mornings than on any other day of the week.21 These findings have been attributed in part to the effects of sudden suspension of caffeine intake during the weekend. In contrast, other studies have found caffeine-withdrawal headache to be rare, with a prevalence of 0.4% in the Norwegian population.22 This raises the question of whether the higher frequency of migraine attacks during the weekend is due to prolonged consumption of caffeine or rather to the interruption of that consumption pattern. The evidence clearly shows that long-term caffeine consumption is a risk factor for migraine transformation. Bigal et al.23 found a positive correlation between daily caffeine consumption and chronic migraine, with an OR of 2.9 (95% CI, 1.5-5.3; P=.0008). Curiously enough, this study also showed that daily caffeine consumption was positively correlated with analgesic-overuse headache, with an OR of 2.2 (95% CI, 1.2-3.9; P=.009). In a study by Scher et al.24, patients with chronic daily headache, especially women younger than 40, were more likely to have been high caffeine consumers before migraine onset (OR, 1.50). These authors found no significant correlation between current caffeine consumption and presence of chronic daily headache. The clinical pattern observed in the study by Scher et al. is consistent with the hypothesis that caffeine consumption constitutes a risk factor for chronic daily headache, given the statistically significant and documented association between caffeine consumption and subsequent headaches. Caffeine-withdrawal headache is not likely to have had an impact on the results of this study since it is a process that resolves within a few days or weeks after caffeine is discontinued.24 In a study in the Japanese population, daily caffeine consumption was also positively correlated with presence of migraine (OR, 2.4).25 All of the above data support the hypothesis that caffeine consumption is a risk factor for chronic daily headache. Questions remain as to whether this phenomenon is due to an exacerbation of primary headache or to progression of analgesic-overuse headache.

ConclusionsLong-term excessive caffeine consumption induces pathophysiological changes in the peripheral and central nervous system that increase cortical hyperexcitability and promote the release of pro-nociceptive neuropeptides, leading to analgesic-overuse headache and increasing the frequency of primary headache attacks. From an epidemiological viewpoint, current evidence is insufficient to conclude that caffeine induces analgesic-overuse headache. There is evidence, however, that long-term caffeine consumption increases risk of transformation for some types of primary headache. Further studies may help determine whether caffeine should be listed among substances that potentially trigger analgesic-overuse headache.

FundingThis study was financed using the authors’ personal resources.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to express our gratitude to those who contributed to this project: to the members of the neurology department and the postgraduate programme in neurology at the Universidad de la Sabana; Dr Roberto Baquero, Dr Erik Sánchez, Dr Javier Vicini, Dr Gustavo Barrios, Dr María Claudia Angulo, Dr Andrés Betancourt, Dr Marta Ramos, Dr Alejandra Guerrero, Dr Luisa Echavarria, Dr Adriana Casallas, Dr Jorge Ruiz. To the Medical School at Universidad de la Sabana; Dr Camilo Osorio, Dr Fernando Ríos, and Dr María José Maldonado. To the patients of the neurology department at Hospital Occidente de Kennedy. To the directors of Hospital Occidente de Kennedy, Dr Juan Ernesto Oviedo, and Dr Wilson Darío Bustos. To the nursing and medical staff in training at Hospital Occidente de Kennedy.

Please cite this article as: Espinosa Jovel CA, Sobrino Mejía FE. Cafeína y cefalea: consideraciones especiales. Neurología. 2017;32:394–398.