The Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome (VKHS) is a systemic granulomatous autoimmune disease, targeting melanocytic self-antigens. Its main symptoms include ocular, neurological, auricular, and integumentary manifestations. The condition presents 4 stages: the prodromal, acute uveitic, convalescent, and chronic recurrent phases. The prodromal stage usually manifests with headache and meningism, with ocular symptoms appearing later.1,2 Considering the relevance of establishing early immunosuppressive treatment to avoid recurrence and prevent eye involvement, it is essential to maintain a high level of clinical suspicion and to establish a correct diagnosis.

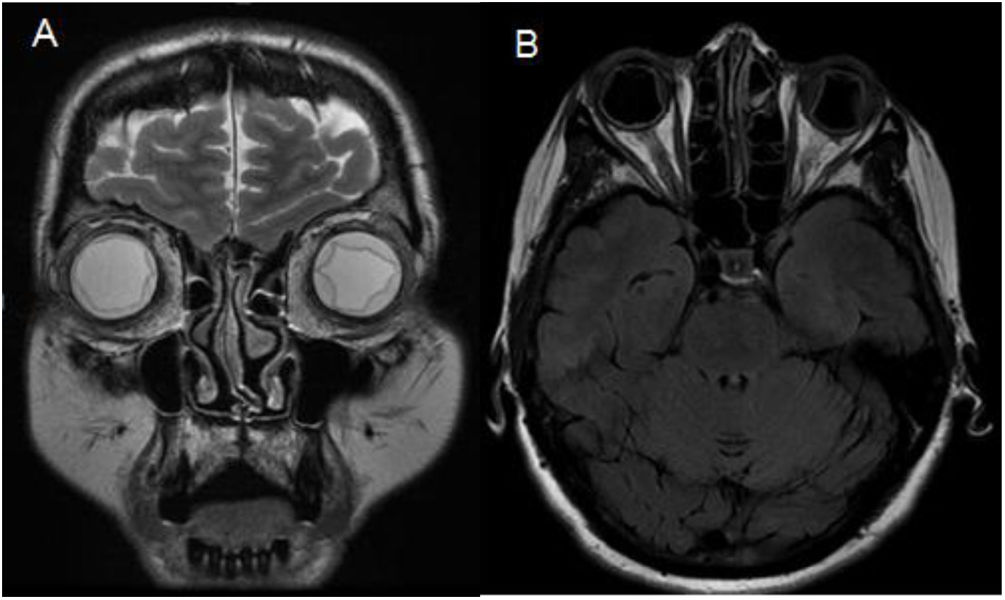

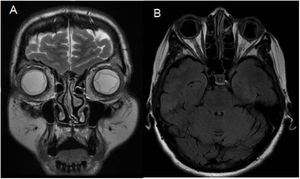

We present the case of a 58-year-old Moldavian woman with history of major depressive disorder and dyslipidaemia without active treatment. She attended the emergency department 3 times due to acute-onset headache, photopsias, and blurred vision. She presented arterial hypertension at all visits. An eye fundus examination revealed bilateral optic disc oedema and the patient was admitted to the neurology department due to suspicion of intracranial hypertension. During admission, a brain MRI study showed bilateral choroidal effusion but no parenchymal lesions (Fig. 1).

Considering the MRI findings, a lumbar puncture was performed, revealing an opening pressure of 20.5 cm H2O. The CSF analysis showed 320 leukocytes/mm3 (predominantly lymphocytes), 10 erythrocytes/mm3, a CSF/plasma glucose ratio of 0.49, and protein level of 1.03 g/L. Cultures and PCR results for neurotropic viruses were negative, as were cytology findings. In the light of these results, we performed an ophthalmological evaluation with optical coherence tomography (OCT) and fluorescein angiography, revealing bilateral panuveitis with choroidal effusion and serous retinal detachment.

Overall, the patient’s symptoms and test findings suggest uveo-meningeal syndrome, with the patient presenting aseptic meningitis, which together with the ophthalmological findings indicates VKHS.

The study was expanded with serology tests for Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, measles, rubella, mumps, Toxoplasma gondii, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, Coxiella, Rickettsia, Brucella, Mycoplasma, HIV, and Treponema pallidum; all findings were negative for active or recent infection. The only exception was Chlamydophila pneumoniae, which showed high IgG titres, suggesting recent infection.

Thus, the patient met diagnostic criteria for incomplete VKHS.3 Treatment was immediately started with intravenous methylprednisolone dosed at 1000 mg/24 h for 5 days, followed by oral prednisone at 1 mg/kg/day for a month and a half, as tapering was necessary due to adverse drug reactions. She also received topical treatment with cycloplegics and dexamethasone. The patient improved considerably after treatment onset, with visual acuity increasing from 0.1 to 0.4 bilaterally at 6 days of treatment and 1/1 at 4 months of treatment. As the patient did not tolerate high-dose corticosteroids, and with a view to better controlling inflammation and choroidal neovascularisation, we added azathioprine to the treatment schedule.4–6 Treatment response was also monitored using OCT, which revealed a fast, remarkable resolution of retinal detachment and choroidal inflammation.

The initial treatment of this syndrome is currently a subject of debate. The classical approach consists of initial treatment with corticosteroids, followed by immunotherapy at later stages. Over the last decade, we have observed a clear correlation between early onset and high-dose intravenous glucocorticoids (between 500 and 1000 mg for 3 days), and initial clinical improvement.7 Furthermore, some recent studies support the use of concomitant therapy with immunosuppressants from onset, as data suggest that this combination therapy is associated with a decrease in the number of late complications.8 However, this is not implemented in everyday clinical practice.

In the case of our patient, we initially used intravenous monotherapy at 1000 mg for 5 days, (longer than the classical exposure time to high-dose immunosuppression), obtaining very good clinical outcomes with resolution of neurological symptoms and the choroidal inflammation shown by OCT.

We should underscore the recent C. pneumoniae infection as a possible trigger of the disease. VKHS is known to be triggered by various (mainly viral) infections, however, we found no cases in the literature that were triggered by C. pneumoniae infection, which has been associated with such other autoimmune diseases as Kawasaki disease or multiple sclerosis.9

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.