The use of low doses of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) was initially proposed in Asian countries in response to racial peculiarities related to the functionality of fibrinogen and coagulation factors that potentially increased the risk of intracerebral haemorrhage, and with a view to saving costs. In view of the controversy over the use of rt-PA below the standard dose, we conducted a literature review of studies promoting the use of low doses or comparing different doses of rt-PA.

DevelopmentWe reviewed 198 abstracts related to the search terms and the full texts of 52 studies published in the last 30 years. We finally included 13 randomised clinical trials aiming to determine the efficacy and safety of the use of rt-PA at different doses in acute stroke, 14 observational cohort studies, 5 meta-analyses, and 3 systematic reviews.

ConclusionsThere is insufficient evidence to classify low doses of rt-PA as superior or at least not inferior to the standard treatment in the management of acute stroke in western populations. More clinical trials are required to determine whether the use of low doses is beneficial in patients with relative contraindications for thrombolytic therapy or other particular circumstances that may increase the risk of intracerebral haemorrhage.

El uso de activador tisular del plasminógeno (rt-PA) a dosis bajas fue propuesto inicialmente en países asiáticos en atención a particularidades raciales relacionadas con la funcionalidad del fibrinógeno y factores de coagulación que contribuyen al riesgo de hemorragias intracerebrales, así como a la intención de ahorrar costos. Ante la controversia sobre el uso de rt-PA por debajo de la dosis estándar, realizamos una revisión de la literatura sobre los estudios que motivaron su uso y aquellos dirigidos a comparar diferentes dosis de rt-PA.

DesarrolloSe revisaron 198 resúmenes relacionados con los términos de búsqueda. Se revisaron 52 publicaciones de texto completo de los últimos 30 años. Se incluyeron 13 ensayos clínicos aleatorizados dirigidos a determinar la eficacia y seguridad del uso de rt-PA a diferentes dosis en el ictus agudo, 14 estudios de cohorte observacionales, 5 metaanálisis y 3 revisiones sistemáticas.

ConclusionesNo se cuenta con evidencia suficiente para catalogar la dosis baja de alteplasa como superior o al menos no inferior que el tratamiento estándar en el manejo del ictus agudo en población occidental. Se requieren más ensayos clínicos para determinar, si el uso de dosis bajas es beneficioso en pacientes con contraindicaciones relativas de terapia trombolítica u otras circunstancias particulares que eleven el riesgo de hemorragias intracerebrales.

After the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) published a study1 demonstrating the benefits of administering recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) (0.9mg/kg) within 3 hours of stroke onset, the US Food and Drug Administration approved its use for the treatment of acute ischaemic stroke in 1996.2 Low-dose rtPA was initially proposed in some Asian countries due to the increased risk in these populations of intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH) secondary to use of fibrinogen and coagulation factors, and the need to reduce costs.3 In Japan, the preference for low-dose rtPA is mainly based on efficacy and safety results from clinical trials using different doses of duteplase (rtPA), now withdrawn from the market,4–6 as well as a wide range of observational studies of alteplase (rtPA), whose results have been compared against those of studies of standard-dose alteplase.7,8

In the light of the controversy about the most appropriate dose of rtPA, we conducted a review of the studies supporting the use of low-dose rtPA and those comparing low-dose and standard-dose rtPA.

MethodsWe systematically searched the PubMed, SCOPUS, EMBASE, and BIREME databases to identify studies of intravenous thrombolysis at different doses. We gathered studies published between January 1992 (publication of the first pilot clinical trials comparing thrombolytics at different doses) and January 2018 using the Spanish keywords “ictus,” “fibrinólisis,” “activador tisular del plasminógeno,” “dosis bajas,” and “dosis estándar”; and English keywords “thrombolytic therapy,” “alteplase,” “standard dose,” “thrombolysis,” “tissue plasminogen activator,” and “fibrinolytic agents.” We excluded all non-peer-reviewed studies and those that did not clearly describe the methodology. Studies with treatment windows longer than 4.5 hours and those using lower-efficacy thrombolytics were also excluded. We made a preliminary selection of studies based on their titles and abstracts and subsequently read the full texts of the articles selected. Our review included randomised controlled clinical trials (RCT), cohort studies, case series, ecological studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses written in English or Spanish.

ResultsWe initially reviewed 198 abstracts, then read the full texts of 52 studies. Six studies were excluded due to early termination or use of treatment windows longer than 4.5 hours. We excluded an additional 12 studies that analysed lower-efficacy thrombolytics. Our review finally included 13 RCTs aiming to determine the efficacy and safety of different doses of alteplase for acute stroke, 14 observational cohort studies, 5 meta-analyses, and 3 systematic reviews.

Standard-dose thrombolysis (0.9mg/kg)Multiple studies have shown the benefit of administering standard-dose alteplase within 4.5 hours of symptom onset.9 One of the earliest studies, the NINDS study (0.9mg/kg of intravenous rtPA against placebo), reports better functional outcomes at 3 months in patients receiving treatment within 3 hours of symptom onset (modified Rankin Scale [mRS] 0-1; OR=1.7; P=.019), although these patients presented a higher rate of ICH (6.4% vs 0.6% in patients receiving placebo treatment; P<.001).

Other studies aimed to establish the most appropriate treatment window for rtPA in acute stroke.10–13 A meta-analysis including 3 of the most important RCTs published at the time (ATLANTIS, ECASS, and NINDS) reports favourable outcomes with standard-dose thrombolysis, even in patients receiving treatment from 3 to 4.5 hours after symptom onset (OR=1.4 [95% CI, 1.1-1.9]).1,12,14,15 In 2008, the ECAS III study13 demonstrated the benefit of alteplase dosed at 0.9mg/kg, with significant efficacy when administered within 4.5 hours of symptom onset and no significant increase in mortality (7.7%, vs 8.4% in the placebo group; P=.68). However, the available evidence suggests that efficacy decreases with greater delays in treatment initiation. A systematic review of 9 RCTs found that the likelihood of a favourable outcome is inversely proportional to the time from symptom onset to treatment initiation (OR=2.55 [95% CI, 1.44-4.52] for treatment administered within 0-90 minutes; OR=1.22 [95% CI, 0.92-1.61] for treatment administered 271-360 minutes after stroke onset).16 After 4.5 hours, the risks of this treatment usually outweigh the benefits, and thrombolysis is therefore contraindicated.2,9,17

Older age, severe stroke, prior stroke, diabetes mellitus, and use of oral anticoagulants have for many years been regarded as contraindications for administering thrombolysis between 3 and 4.5 hours from stroke onset.17 These factors were established as exclusion criteria by the authors of the ECAS III study as they were arbitrarily considered to increase the risk of ICH. According to recent studies and clinical practice guidelines, however, standard-dose fibrinolysis is effective and safe for these patients.9,18,19

Low-dose thrombolysisIn the early 1990s in Japan, several RCTs comparing different doses of rtPA showed that 20 MIU duteplase (0.6mg/kg alteplase) was efficacious for treating acute embolic stroke without significantly increasing the risk of haemorrhage.4,5 In a subsequent study including a larger sample (N=113), low-dose duteplase (20IU) showed similar efficacy to 30IU duteplase (0.9mg/kg alteplase) for treating arterial occlusion, and was associated with a significantly lower incidence of ICH (3.6% vs 13.8%).6 After the publication of these results, the use of duteplase at doses above 20 MIU (or the equivalent dose of alteplase) was limited in Japan.

When the US Food and Drug Administration approved the use of alteplase for acute stroke, and duteplase was withdrawn from the market due to patent-related issues, researchers in Japan began to explore the efficacy and safety of different doses of alteplase. In view of the ethical issues involved in the use of placebo or control groups, the new studies compared case series against historical control groups taken from older clinical trials and patient series from Western studies of standard-dose alteplase.7,8,20,21

One of the most relevant publications was the J-ACT study,8 in which 103 patients with acute stroke (mainly cardioembolic) received 0.6mg/kg of intravenous alteplase; results were compared against those of a meta-analysis of international studies and against the treatment group of the NINDS study. The percentage of patients scoring 0-1 on the mRS at 3 months was 36.9% (90% CI, 29.1%-44.7%) and the incidence of ICH within 36 hours of treatment initiation was 5.8% (90% CI, 2%-9.6%); both values are similar to those obtained in the treatment group of the NINDS study (Table 1) and the meta-analysis.1,8,12,22–28 However, the 3-month mortality rate was lower in the J-ACT study (9.7%, vs 17% in the NINDS and 10%-17% in the meta-analysis). Despite the limitations of observational studies, the authors showed that alteplase dosed at 0.6mg/dL was as efficacious and safe as standard doses in their population.8 Based on these results, the Japanese healthcare authorities approved the use of alteplase dosed at 0.6mg/kg for the treatment of acute stroke. Meanwhile, the researchers conducted the second phase of the study,20 as well as the J-MARS post-marketing registration study,7 whose results were compared against those of the SIST-MOST study, a European pharmacosurveillance study of standard-dose alteplase.

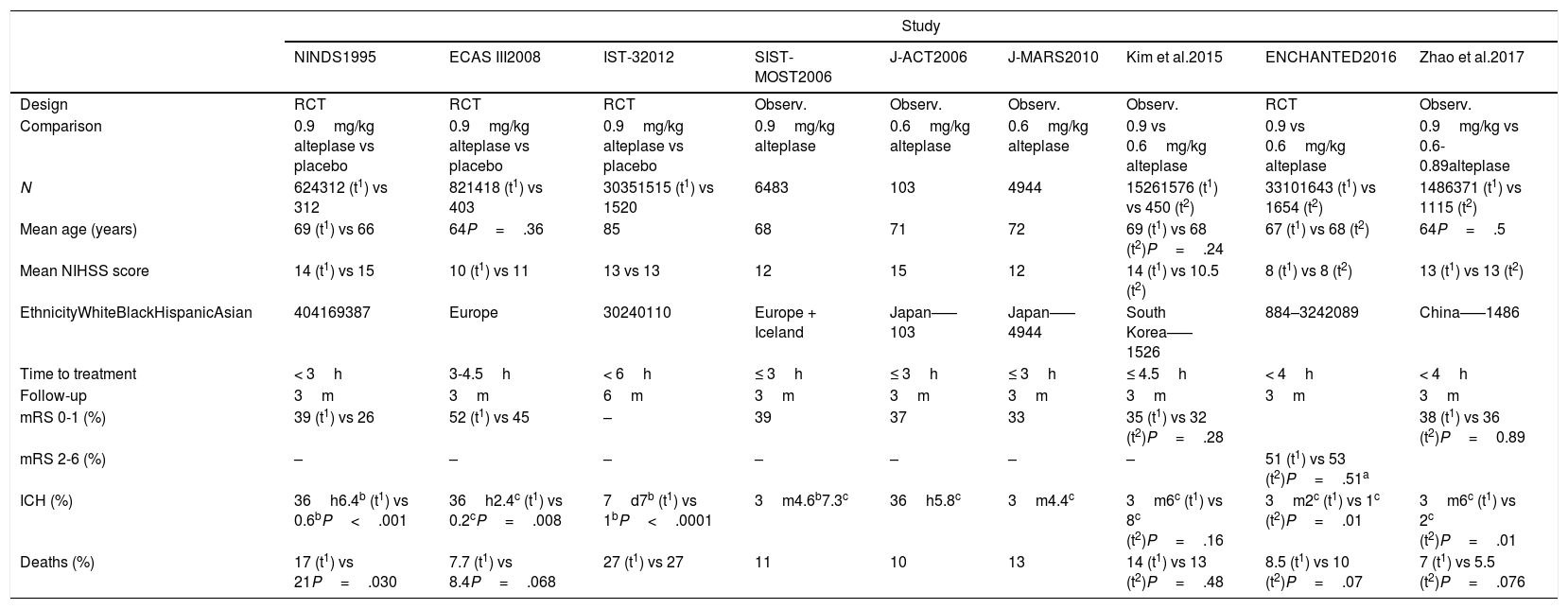

Characteristics of the studies aimed at determining the efficacy and safety of different doses of alteplase.

| Study | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NINDS1995 | ECAS III2008 | IST-32012 | SIST-MOST2006 | J-ACT2006 | J-MARS2010 | Kim et al.2015 | ENCHANTED2016 | Zhao et al.2017 | |

| Design | RCT | RCT | RCT | Observ. | Observ. | Observ. | Observ. | RCT | Observ. |

| Comparison | 0.9mg/kg alteplase vs placebo | 0.9mg/kg alteplase vs placebo | 0.9mg/kg alteplase vs placebo | 0.9mg/kg alteplase | 0.6mg/kg alteplase | 0.6mg/kg alteplase | 0.9 vs 0.6mg/kg alteplase | 0.9 vs 0.6mg/kg alteplase | 0.9mg/kg vs 0.6-0.89alteplase |

| N | 624312 (t1) vs 312 | 821418 (t1) vs 403 | 30351515 (t1) vs 1520 | 6483 | 103 | 4944 | 15261576 (t1) vs 450 (t2) | 33101643 (t1) vs 1654 (t2) | 1486371 (t1) vs 1115 (t2) |

| Mean age (years) | 69 (t1) vs 66 | 64P=.36 | 85 | 68 | 71 | 72 | 69 (t1) vs 68 (t2)P=.24 | 67 (t1) vs 68 (t2) | 64P=.5 |

| Mean NIHSS score | 14 (t1) vs 15 | 10 (t1) vs 11 | 13 vs 13 | 12 | 15 | 12 | 14 (t1) vs 10.5 (t2) | 8 (t1) vs 8 (t2) | 13 (t1) vs 13 (t2) |

| EthnicityWhiteBlackHispanicAsian | 404169387 | Europe | 30240110 | Europe + Iceland | Japan–––103 | Japan–––4944 | South Korea–––1526 | 884–3242089 | China–––1486 |

| Time to treatment | < 3h | 3-4.5h | < 6h | ≤ 3h | ≤ 3h | ≤ 3h | ≤ 4.5h | < 4h | < 4h |

| Follow-up | 3m | 3m | 6m | 3m | 3m | 3m | 3m | 3m | 3m |

| mRS 0-1 (%) | 39 (t1) vs 26 | 52 (t1) vs 45 | – | 39 | 37 | 33 | 35 (t1) vs 32 (t2)P=.28 | 38 (t1) vs 36 (t2)P=0.89 | |

| mRS 2-6 (%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 51 (t1) vs 53 (t2)P=.51a | |

| ICH (%) | 36h6.4b (t1) vs 0.6bP<.001 | 36h2.4c (t1) vs 0.2cP=.008 | 7d7b (t1) vs 1bP<.0001 | 3m4.6b7.3c | 36h5.8c | 3m4.4c | 3m6c (t1) vs 8c (t2)P=.16 | 3m2c (t1) vs 1c (t2)P=.01 | 3m6c (t1) vs 2c (t2)P=.01 |

| Deaths (%) | 17 (t1) vs 21P=.030 | 7.7 (t1) vs 8.4P=.068 | 27 (t1) vs 27 | 11 | 10 | 13 | 14 (t1) vs 13 (t2)P=.48 | 8.5 (t1) vs 10 (t2)P=.07 | 7 (t1) vs 5.5 (t2)P=.076 |

d: days; h: hours; m: months; mRS: modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; observ.: observational; RCT: randomised controlled trial.

t1: standard-dose alteplase.

t2: low-dose alteplase.

In the J-MARS study,7 the percentages of patients with ICH at 3 months and those with favourable outcomes were similar to those reported in the SIST-MOST study. However, as reported by other Japanese studies,29,30 the percentage of cases of ICH was proportional to each recruiting centre's experience with thrombolysis.7,31 Despite a high drop-out rate, the results show that alteplase dosed at 0.6mg/kg is associated with low rates of ICH in Japanese populations, while offering similar efficacy and safety to that of standard-dose alteplase in Europe.

Interestingly, the results of multiple observational studies comparing different doses of alteplase in other regions of Asia do not support the hypothesis that low-dose alteplase reduces the incidence of ICH. A study of 1526 patients from South Korea found that low- and standard-dose alteplase display similar efficacy and safety in terms of ICH incidence (8.4% for low-dose alteplase vs 6.4% for standard-dose alteplase; P=.16) and mortality (12.7% vs 14%; P=.48).21 Furthermore, a meta-analysis of observational studies conducted in China, Vietnam, Singapore, Thailand, and Korea32 found no significant differences between the low-dose (0.6-0.85mg/kg) and standard-dose rtPA groups in terms of the rates of good functional outcomes (mRS 0-1) at 3 months (OR=0.88; 95% CI, 0.71-1.11), ICH (OR=1.19; 95% CI, 0.76-1.87), and mortality at 3 months (OR=0.91; 95% CI, 0.73-1.12).

The recently published ENCHANTED study included patients younger than 80 years with mild-to-moderate stroke (mean NIHSS score of 8)33; 63% of the patients were from Asia and only 10% were recruited in Latin America. The study compared the effects of 0.6mg/kg alteplase against the standard dose. To confirm the non-inferiority hypothesis proposed by the authors, the upper limit of the 95% CI for the odds ratio of the primary outcome of death or severe disability had to be ≤ 1.14 (margin derived from Cochrane meta-analyses of alteplase trials with effects on poor outcomes reported). Although the incidence of ICH was significantly lower in the low-dose group, mortality rates were similar between groups. Furthermore, the study failed to demonstrate that low-dose alteplase was non-inferior to standard-dose alteplase, as the standard dose showed lower rates of mortality and severe disability (51.1% vs 53.2%; OR=1.09; 95% CI, 0.95-1.25; P=.51 for non-inferiority). Similar results were reported by a recent retrospective observational study of 1486 patients in China; the study found no differences in functional outcomes or death at 90 days between 0.9mg/kg alteplase and low-dose alteplase. However, the incidence of ICH was significantly lower in the low-dose group.33,34

Future perspectivesThe Thrombolysis for Acute Wake-Up and Unclear-Onset Strokes With Alteplase at 0.6mg/kg Trial (THAWS) is an RCT currently underway in Japan. Intended as a complement to the WAKE UP study, the THAWS trial aims to include 300 patients with acute wake-up and unclear-onset strokes who are eligible for thrombolysis according to MRI findings. The researchers administer 0.6mg/kg intravenous alteplase to patients with DWI-ASPECT scores ≥ 5 and not presenting hyperintensities on FLAIR sequences (these findings indicate stroke of less than 4.5 hours’ progression). The study is due to be completed in March 2020 and aims to determine the efficacy and safety of low-dose thrombolysis in these patients.

ConclusionInsufficient evidence is available to categorically state that low-dose alteplase is superior (or at least non-inferior) to standard-dose alteplase for treating acute stroke in Western populations. None of the studies included in this review reports significant reductions in mortality rates with low-dose alteplase as compared to standard doses.

The low rates of ICH associated with low-dose rtPA suggest that use of low doses of alteplase may be a reasonable option in Asian patients. Further research is needed to support its use in patients with contraindications for intravenous thrombolysis, those eligible for thrombolytic therapy and undergoing intra-arterial procedures, or patients with any other circumstances increasing the risk of ICH.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Montalván Ayala V, Rojas Cheje Z, Aldave Salazar R. Controversias en enfermedad cerebrovascular: rt-PA a dosis bajas vs. dosis estándar en el tratamiento del ictus agudo. Una revisión de la literatura. Neurología. 2022;37:130–135.