The Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test (RBMT) is a short, ecologically valid memory test battery that can provide data about a subject's memory function in daily life. We used RBMT to examine daily memory function in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), Alzheimer disease (AD), and in healthy controls. We also evaluated differences between the memory profiles of subjects whose MCI remained stable after 1 year and those with conversion to AD.

Patients and methodsSample of 91 subjects older than 60 years: 30 controls, 27 MCI subjects and 34 AD patients. Subjects were assessed using MMSE and RBMT.

ResultsThe 40 men and 51 women in the sample had a mean age of 74.29±6.71 and 5.87±2.93 years of education. For the total profile, screening RBMT scores (P<.001) and total MMSE scores (P<.05), control subjects scored significantly higher than those with MCI, who in turn scored higher than AD patients. In all subtests, the control group (P<.001) and MCI group (P<.05) were distinguishable from the AD group. Prospective, retrospective, and orientation subtests found differences between the MCI and control groups (P<.05). MCI subjects who progressed to AD scored lower at baseline on the total RBMT and MMSE, and on name recall, belongings recall, story immediate recall, route delayed recall, orientation (P<.05), face recognition, story delayed recall, and messages delayed recall sections (P<.01).

ConclusionsRBMT is an ecologically valid episodic memory test that can be used to differentiate between controls, MCI subjects, and AD subjects. It can also be used to detect patients with MCI who will experience progression to AD.

El Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test (RBMT) es una batería ecológica breve que permite predecir el funcionamiento mnésico del sujeto en la vida diaria. Evaluamos mediante el RBMT el funcionamiento mnésico en la vida diaria, de pacientes con deterioro cognitivo leve (DCL), enfermedad de Alzheimer (EA) y sujetos sanos, así como las diferencias entre perfiles mnésicos de los sujetos DCL estables al año y los que progresarán a EA.

Pacientes y métodosMuestra de 91 sujetos con 60 o más años, 30 controles, 27 DCL y 34 pacientes con EA. Se evalúa a los sujetos mediante MMSE y RBMT.

ResultadosCuarenta hombres y 51 mujeres, con edad y escolaridad media de 74,29±6,71 y 5,87±2,93 años, respectivamente. En las puntuaciones totales, perfil y global del RBMT (p<0,001) y del MMSE (p<0,05), los sujetos control puntúan significativamente más alto que los DCL y estos que los EA. En todos los subtest, los controles (p<0,001) y DCL (p<0,05) se diferencian de la EA. Subtest prospectivos, retrospectivos y de orientación diferencian al grupo control del DCL (p<0,05). Los sujetos DCL que progresan a EA puntúan más bajo en la exploración inicial en las puntuaciones totales del RBMT, MMSE y en el recuerdo del nombre, objeto personal, recuerdo inmediato de la historia, recuerdo diferido del recorrido y orientación (p<0,05), reconocimiento de dibujos, recuerdo diferido de la historia y del mensaje (p<0,01).

ConclusionesRBMT es una prueba ecológica de memoria episódica útil para diferenciar entre sí sujetos controles/DCL/EA, que además permite detectar a los pacientes con DCL que progresan a EA.

The recent revision of diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer disease (AD), and the new definitions of the preclinical and prodromal phases, recommends the use of episodic memory tests in cases of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), since this is the most frequent impairment in patients who will progress to AD (MCI due to AD). Evaluation of other cognitive functions such as language, executive functions, attention, and visuospatial functions, together with the use of biomarkers, will help physicians provide earlier and more efficient diagnoses.1–6

Traditional episodic memory tests that assess immediate recall, delayed recall,4 and recognition,7 as well as recall of verbal information8 or pictures,9,10 are recommended for assessing patients with MCI. Alterations in prospective memory (whether isolated11 or together with alterations in retrospective memory12) and changes in visuospatial memory have also been suggested as cognitive markers of MCI due to AD. A recently proposed strategy is to combine several episodic memory tests to increase discriminatory potential8 and identify the profile associated with each MCI subtype.13 In the same way, during the neuropsychological examination for MCI, doctors should administer tests that permit long-term follow-up4 and do not exhibit a practice effect.14 Tests should also reflect cognitive performance in daily life.15 The Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test (RBMT), a brief test battery for episodic memory, meets these requirements.

The RBMT is classified as an ecological assessment. These tests evaluate cognitive functions using tasks similar to those in daily life, demonstrate high levels of ecological validity, and combine the scientific rigour of traditional neuropsychological tests (standardised administration and correction) with the observational techniques used in behavioural psychology, such as simulating situations similar to those in daily life. Unlike traditional tests, RBMT does not follow an established memory model and it does not focus on whether the individual is able to complete the task. Rather, it analyses how the individual performs the task and how memory impairment affects the individual's daily functioning. RBMT lets us identify aspects that may be subject to cognitive intervention and that reflect changes over time (the test has 4 parallel forms). These features make it ideal for use in rehabilitation therapy. The test can be administered quickly and since it involves familiar activities, examinees usually do not experience frustration reactions, unlike in traditional tests.16 RBMT subtests assess prospective memory, retrospective memory, orientation, visuospatial memory, and short- and/or long-term memory. They also include immediate and delayed recall and recognition tests, as well as recall of words and images. The 12 subtests of RBMT are recalling first name (item 1) and second name (item 2) of the person in a picture 20minutes after it has been shown to the examinee; recalling where their belongings have been hidden (the examinee must request and locate the objects when the examiner utters a sentence established 25minutes previously) (item 3); remembering to ask for an appointment when an alarm sounds after 20minutes (item 4); recognising 10 pictures from a set of 20 previously shown to the examinee (item 5); remembering a story with 21 ideas to test immediate recall (just after reading it) and delayed recall (20minutes later) (item 6); recognising 5 faces from the 10 shown previously (item 7); immediate recall (item 8) and delayed recall (item 9) of the same route; immediate and delayed recall of a message (remembering to pick up an envelope and place it in a specific place) (item 10); 9 questions to test orientation (item 11), and recalling the date (item 12).17

Previous studies with RBMT demonstrated a good correlation with the traditional episodic memory tests that are typically used in diagnosis. Examples include the revised Wechsler Memory Scale,18 the memory subtest of the Luria-Nebraska neuropsychological battery,19 and the memory scales and total score on CAMCOG.20 RBMT also discriminates between diseases such as vascular and non-vascular dementia,21 AD, cognitive impairment associated with epilepsy, and brain injury.18,19 Regarding MCI, previous studies from Japan22 and Brazil20 show that both the total profile score and total screening score can be used to differentiate between individuals with MCI, AD, and healthy controls. This supports using these tests for diagnosing MCI.20,22 Regarding the profile of abnormal subtest results indicative of MCI, a test set has been proposed to distinguish between healthy individuals, those with MCI, and those with AD. This set includes a prospective memory subtest (appointment recall, immediate and delayed recall of a message, and remembering hidden belongings),11 free recall subtest (delayed recall of a story is recommended as the best tool for distinguishing individuals with MCI from controls, while immediate recall of a story is the best tool for identifying subjects with MCI due to AD),22 and the prospective subtest on appointment recall. Added to the above are the retrospective subtests for story and route free recall (immediate and delayed).20

Our study aims to evaluate differences in episodic memory in patients with MCI or AD, compared to a control group, by means of this ecologically valid assessment tool. It also assesses the utility of the different subtests with the same aim and also to determine whether differences already exist at baseline in patients with MCI who progress to a clinical diagnosis of AD after one year of follow-up.

Subjects and methodsProspective study of 91 individuals aged 60 years or older, consecutively selected during a 6-month period from the patients examined in the dementia diagnostic unit. The sample includes 34 patients diagnosed with probable AD according to criteria established by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke (AD and Related Disorders Association [NINCDS-ADRDA]).23 Another 27 patients presented mild cognitive impairment according to Petersen et al.,24 and there were also 30 controls.

Of the 92 patients with early stage AD or MCI who attended that unit during the specified period, 75 met the inclusion criteria and 61 of them agreed to participate in the study. Volunteers for the control group were recruited among patients’ companions aged 60 years or older who were not being treated by the unit or who expressed no subjective concerns about their memory. We excluded first-degree relatives. Of the 52 individuals invited to participate, 13 declined and 19 did not meet the criteria. Exclusion criteria for all groups were uncorrected acute vision or hearing impairment; personal history of psychiatric, neurological, or systemic disease associated with neuropsychological impairment; history of alcohol and/or drug abuse; and illiteracy. Control subjects, according to the neurologist's medical opinion, do not present affective symptoms or behavioural or cognitive changes. This was established when patients were interviewed following the care assessment protocol.

Diagnosis of subjects with MCI and AD was performed by an interdisciplinary care team from our unit that included a neurologist, a neuropsychologist, and a consultant psychiatrist. Subjects visited our unit because of cognitive and/or behavioural complaints; most were referred by their primary care doctors. Diagnostic evaluation included a general neuropsychological test, neurological evaluation, blood test (thyroid-stimulating hormone, syphilis serological test, folic acid, and vitamin B12) and structural neuroimaging study (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging as chosen by the lead doctor).

Tests administered by the neurology department included the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)25; Blessed dementia scale26; abbreviated neuropsychiatric inventory27; Tinetti scale28; Hachinski ischaemic scale29; global deterioration scale30; IADL scale of Lawton and Brody31; and the second version of the Rapid Disability Rating Scale.32 The general neuropsychological examination included the MMSE time and spatial orientation subtest25; the 15-item version of the Boston naming test33 and the Boston diagnostic aphasia examination subtest for auditory comprehension of commands34; WAIS forward and backward digit span and similarity subtests35; Poppelreuter's overlapping figures test36; subtests on constructive praxis in copying, symbolic gesture, imitation of bilateral postures, and animal naming by category from the Barcelona Test–Integrated programme for neuropsychological examination–(PIENB)37; Rey auditory verbal learning test38; lexical fluency test of words beginning with ‘P’ in one minute39; and the Luria-Nebraska battery subtest on motor functions of the hand to measure the dynamic organisation of the motor act.36

Individuals who met inclusion criteria and signed their informed consent then completed the MMSE,25 Reisberg's Global Deterioration Scale,30 and the 12 RBMT subtests mentioned previously.17 All tests were administered in a controlled environment during a single 45-minute session. Tests were scored by a neurologist other than the one who performed the diagnostic evaluation. MMSE25 and RBMT17 were administered on two different occasions, at baseline and at 12 months. For the RBMT, we used Form A (baseline) and Form D (12 months), selected at random. From the direct scores obtained in the 12 subtests, we calculated the total screening score (range, 0-24) and the total profile score (range, 0-12).17 Control subjects were also tested with the Lawton and Brody IADL scale31 at the start of the evaluation.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 12.0 for Windows. We analysed descriptive statistics for scores obtained by each group on every test and performed intergroup cross-sectional comparisons using ANOVA (for parametric data) or Mann-Whitney test, chi-square test or Fisher's exact test for dichotomous variables (non-parametric data). Longitudinal comparison of parametric items was performed with the t-test; the Wilcoxon test was used for non-parametric data, and the McNemar test for dichotomous variables. Using results from the ROC curve, we identified the most suitable cut-off points based on the sensitivity and specificity of each cut-off point. Comparisons were considered statistically significant for P≤.05.

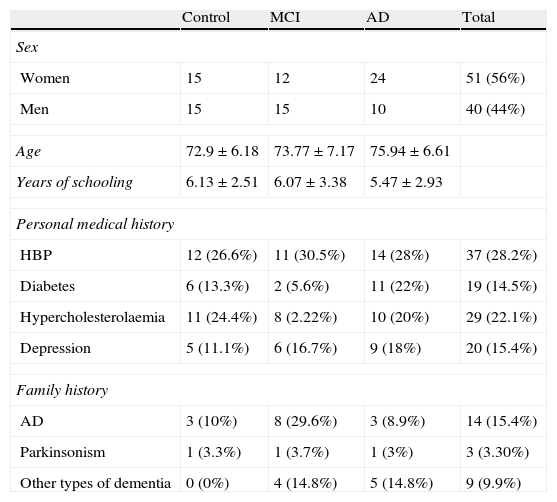

ResultsThe sample consists of 40 men and 51 women distributed in 3 groups (control, MCI, and AD), with a mean age of 74.29±6.71 years and mean years of schooling of 5.87±2.93. Table 1 lists patients’ sociodemographic characteristics. There are no significant differences on age, schooling years or sex between the 3 groups (P>.05). However, significant intergroup differences can be found for the MMSE score and the total RBMT profile and screening scores (P<.001) (Table 2). The intergroup comparison shows that values from the MCI and control groups are significantly higher than in the AD group (P>.001). The control group had significantly better RBMT profile and screening scores, as well as a better MMSE (P>.001 and P>.05, respectively).

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample

| Control | MCI | AD | Total | |

| Sex | ||||

| Women | 15 | 12 | 24 | 51 (56%) |

| Men | 15 | 15 | 10 | 40 (44%) |

| Age | 72.9±6.18 | 73.77±7.17 | 75.94±6.61 | |

| Years of schooling | 6.13±2.51 | 6.07±3.38 | 5.47±2.93 | |

| Personal medical history | ||||

| HBP | 12 (26.6%) | 11 (30.5%) | 14 (28%) | 37 (28.2%) |

| Diabetes | 6 (13.3%) | 2 (5.6%) | 11 (22%) | 19 (14.5%) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 11 (24.4%) | 8 (2.22%) | 10 (20%) | 29 (22.1%) |

| Depression | 5 (11.1%) | 6 (16.7%) | 9 (18%) | 20 (15.4%) |

| Family history | ||||

| AD | 3 (10%) | 8 (29.6%) | 3 (8.9%) | 14 (15.4%) |

| Parkinsonism | 1 (3.3%) | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (3%) | 3 (3.30%) |

| Other types of dementia | 0 (0%) | 4 (14.8%) | 5 (14.8%) | 9 (9.9%) |

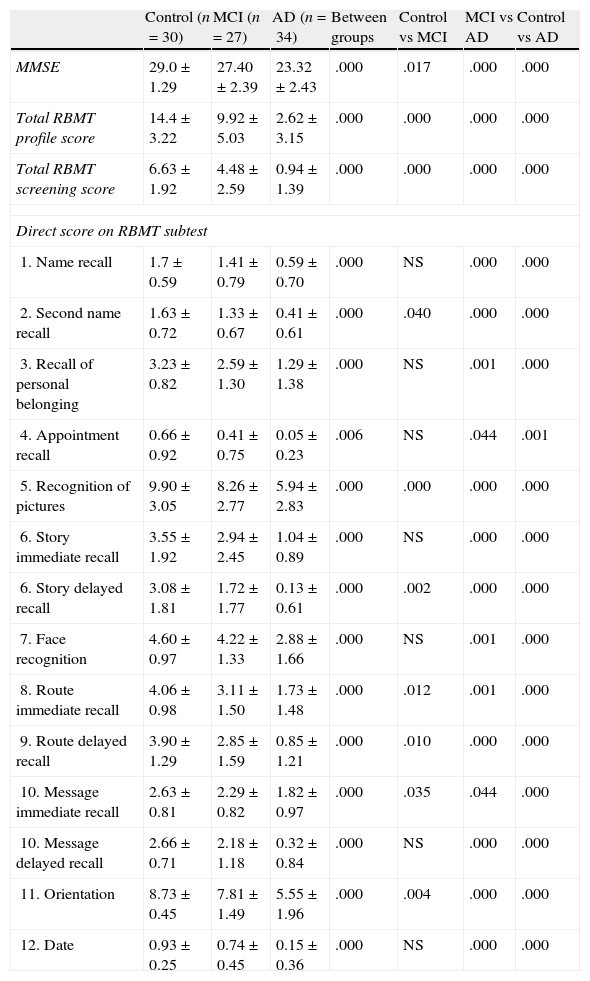

MMSE and RBMT results and comparison between groups

| Control (n=30) | MCI (n=27) | AD (n=34) | Between groups | Control vs MCI | MCI vs AD | Control vs AD | |

| MMSE | 29.0±1.29 | 27.40±2.39 | 23.32±2.43 | .000 | .017 | .000 | .000 |

| Total RBMT profile score | 14.4±3.22 | 9.92±5.03 | 2.62±3.15 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 |

| Total RBMT screening score | 6.63±1.92 | 4.48±2.59 | 0.94±1.39 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 |

| Direct score on RBMT subtest | |||||||

| 1. Name recall | 1.7±0.59 | 1.41±0.79 | 0.59±0.70 | .000 | NS | .000 | .000 |

| 2. Second name recall | 1.63±0.72 | 1.33±0.67 | 0.41±0.61 | .000 | .040 | .000 | .000 |

| 3. Recall of personal belonging | 3.23±0.82 | 2.59±1.30 | 1.29±1.38 | .000 | NS | .001 | .000 |

| 4. Appointment recall | 0.66±0.92 | 0.41±0.75 | 0.05±0.23 | .006 | NS | .044 | .001 |

| 5. Recognition of pictures | 9.90±3.05 | 8.26±2.77 | 5.94±2.83 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 |

| 6. Story immediate recall | 3.55±1.92 | 2.94±2.45 | 1.04±0.89 | .000 | NS | .000 | .000 |

| 6. Story delayed recall | 3.08±1.81 | 1.72±1.77 | 0.13±0.61 | .000 | .002 | .000 | .000 |

| 7. Face recognition | 4.60±0.97 | 4.22±1.33 | 2.88±1.66 | .000 | NS | .001 | .000 |

| 8. Route immediate recall | 4.06±0.98 | 3.11±1.50 | 1.73±1.48 | .000 | .012 | .001 | .000 |

| 9. Route delayed recall | 3.90±1.29 | 2.85±1.59 | 0.85±1.21 | .000 | .010 | .000 | .000 |

| 10. Message immediate recall | 2.63±0.81 | 2.29±0.82 | 1.82±0.97 | .000 | .035 | .044 | .000 |

| 10. Message delayed recall | 2.66±0.71 | 2.18±1.18 | 0.32±0.84 | .000 | NS | .000 | .000 |

| 11. Orientation | 8.73±0.45 | 7.81±1.49 | 5.55±1.96 | .000 | .004 | .000 | .000 |

| 12. Date | 0.93±0.25 | 0.74±0.45 | 0.15±0.36 | .000 | NS | .000 | .000 |

NS, not statistically significant.

Table 2 also shows the scores each group obtained on the different RBMT subtests. All scores show significant differences between groups (P<.01). In general, both the control group and MCI group obtained significantly higher scores on all scales than the AD group, with P≤.0001 and with P<.05 for appointment recall and message immediate recall in the comparison between MCI and AD groups. A comparison between the control and MCI groups reveals that controls obtain significantly higher scores with P≤.01 for picture recognition, story delayed recall, route delayed recall and orientation, and with P<.05 for scores for second name recall, route immediate recall, and message immediate recall.

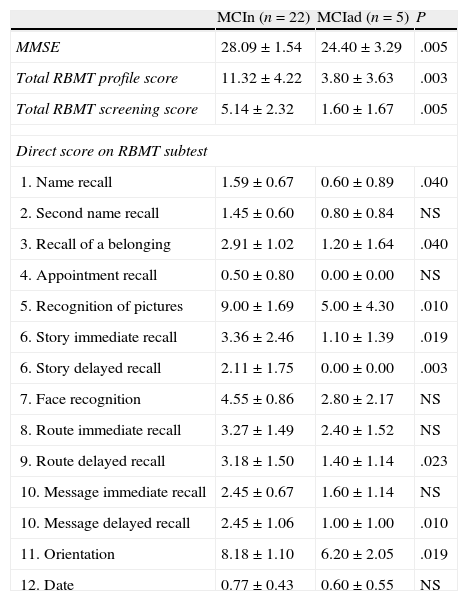

When comparing scores obtained by MCI subjects who remained stable and those who progressed to AD in a year (Table 3), we observed differences in MMSE scores and the total RBMT profile and screening scores (P≤.01). At the level of the different subtests, we observe significantly lower scores (P<.05) in the MCI group that progressed to AD for first name recall, recall of belongings, story immediate recall, route delayed recall, and orientation, with P<.01 for picture recognition, story delayed recall, and message delayed recall.

Results on MMSE and RBMT from MCI patients who remain stable vs patients who progress to AD

| MCIn (n=22) | MCIad (n=5) | P | |

| MMSE | 28.09±1.54 | 24.40±3.29 | .005 |

| Total RBMT profile score | 11.32±4.22 | 3.80±3.63 | .003 |

| Total RBMT screening score | 5.14±2.32 | 1.60±1.67 | .005 |

| Direct score on RBMT subtest | |||

| 1. Name recall | 1.59±0.67 | 0.60±0.89 | .040 |

| 2. Second name recall | 1.45±0.60 | 0.80±0.84 | NS |

| 3. Recall of a belonging | 2.91±1.02 | 1.20±1.64 | .040 |

| 4. Appointment recall | 0.50±0.80 | 0.00±0.00 | NS |

| 5. Recognition of pictures | 9.00±1.69 | 5.00±4.30 | .010 |

| 6. Story immediate recall | 3.36±2.46 | 1.10±1.39 | .019 |

| 6. Story delayed recall | 2.11±1.75 | 0.00±0.00 | .003 |

| 7. Face recognition | 4.55±0.86 | 2.80±2.17 | NS |

| 8. Route immediate recall | 3.27±1.49 | 2.40±1.52 | NS |

| 9. Route delayed recall | 3.18±1.50 | 1.40±1.14 | .023 |

| 10. Message immediate recall | 2.45±0.67 | 1.60±1.14 | NS |

| 10. Message delayed recall | 2.45±1.06 | 1.00±1.00 | .010 |

| 11. Orientation | 8.18±1.10 | 6.20±2.05 | .019 |

| 12. Date | 0.77±0.43 | 0.60±0.55 | NS |

MCIad, MCI subjects who progress to AD; MCIn, subjects who do not progress to AD; NS, not significant.

In the follow-up study, MCI subjects who remained stable after 12 months obtained a score of 26.14±3.27 on the MMSE, a total RBMT profile score of 12.91±5.44, and a total RBMT screening score of 5.91±2.51. On the other hand, the score for the MCI group that converted in one year is 21.00±4.74 on the MMSE, 3.20±3.35 on the total RBMT profile, and 2.20±1.48 on the total RBMT screening. Comparing both MMSE and RBMT evaluations between the 2 groups reveals no significant differences, not even on the subtests. Total RBMT scores for the 31 subjects with AD who underwent both evaluations are 2.48±2.87 in the profile score and 0.87±1.23 in the screening score at baseline, and 1.39±2.03 in the profile score and 0.74±0.93 in the screening score at follow-up (three patients from this group had been lost to the study at the time of the second evaluation). MMSE score at baseline is 25.00±3.17 compared to 23.74±4.97 at 12 months. Differences between the 2 MMSE assessments and the 2 total RBMT profile scores are significant (P<.05). Regarding RBMT subtests, only scores for recall of belongings (mean 1.39±1.41 at baseline and 0.91±1.11 at follow-up) and picture recognition (mean 6.16±2.76 at baseline and 4.64±3.02 at follow-up) show significant differences between the two evaluations in the AD group (P<.05).

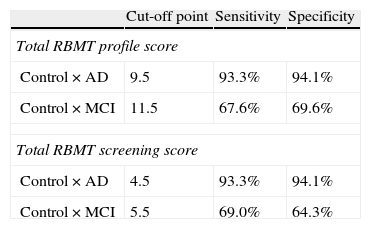

According to the results obtained in ROC curve analysis (Table 4), the best cut-off point for distinguishing between control subjects and AD patients using the total RBMT score is 9.5, with a sensitivity of 93.3% and specificity of 94.1%; for the total RBMT screening, the cut-off point is 4.5, also with a sensitivity of 93.3% and specificity of 94.1%. The cut-off point for distinguishing control subjects from MCI subjects was 11.5 on the total RBMT profile score, with a sensitivity of 67.6% and specificity of 69.5%. For the total RBMT screening score, it was 5.5 with a sensitivity of 69.0% and specificity of 64.3%.

DiscussionThe aim of our study was to determine if the RBMT ecological assessment could be useful in distinguishing between healthy subjects, those with MCI, and those with AD, and to evaluate whether it could contribute to early detection of AD.

Our results show that the RBMT distinguishes between controls, subjects with MCI, and subjects with AD. Total scores (profile and screening) obtained by individuals with MCI are higher than those of AD subjects and lower than those of control subjects. These findings coincide with results from Kazui et al. and Yassuda et al. Regarding RBMT subtests, AD subjects had significantly lower scores on all RBMT subtests than MCI and control subjects, as in the study by Yassuda et al. In contrast, results from Kazui et al. show that most subtest scores do not distinguish between patients with MCI or AD. Yassuda et al. propose subtests for free recall (story and route) and prospective memory (appointment recall), while Kazui et al. propose using delayed recall subtests that do not include prospective memory to identify subjects with MCI.20,22 Our study also proposes using free and delayed recall, immediate recall, and recognition subtests to distinguish between controls, patients with MCI, and patients with AD; it also proposes a prospective and retrospective memory subtest, as do Yassuda et al. and Martins and Damasceno.12,20 These subtests are last name recall, picture recognition, story delayed recall, route immediate and delayed recall, message immediate recall, and orientation.

Results coincide with those obtained by studies of MCI using traditional episodic memory tests. Such studies recommend using immediate and delayed recall tests, recognition tests, word and picture recall, and visual and spatial memory tests, in addition to using different memory tests in the evaluation.7,13,15 Regarding cut-off points, data on the sensitivity and specificity of total profile and screening scores in our study, as in the study by Yassuda et al.,20 show these cut-off points to be highly accurate for identifying AD subjects and moderately accurate for identifying MCI subjects.

One original aspect of our study, compared to other contributions using the RBMT, is that we compare scores obtained by MCI patients who maintain that diagnosis for a year to scores from patients who progress to AD. RBMT distinguishes subjects diagnosed with MCI who remain stable from those who progress to AD; the latter's total profile and screening scores at baseline are significantly poorer. RMBT also lets us identify the memory profile of patients whose MCI is due to AD in the baseline examination. The following tests are recommended for use in routine MCI screenings: belongings recall, message delayed recall (prospective memory), and name recall, picture recognition, story immediate and delayed recall, route delayed recall, and orientation (retrospective memory).

Regarding longitudinal follow-up, RBMT, like the MMSE, reveals the progression of memory loss in AD in a one-year period, both for the total profile score on the belongings subtest and the picture recognition subtest. In both groups with MCI, we observe no significant differences between scores. This highlights the necessity for evaluating other cognitive functions during short-term follow-up of MCI patients, as stated by Summers and Saunders.6

RBMT combines the standard administration and correction procedures of traditional neurospychological tests of episodic memory with greater ecological validity. The test allows us to predict behaviour since it simulates daily life situations, which in turn favours the patient's cooperation and decreases frustration. It also lets us identify compensatory strategies and aids that may benefit the patient and design neuropsychological rehabilitation programmes to stimulate and promote independence in activities of daily living as long as the disease permits. Since the RBMT's results resemble those of traditional tests and it meets the requirements proposed in the new AD criteria,1–4 experts recommend using it in daily clinical practice. We should not forget that one of the main limitations of traditional tests is the low generalisability of their results.16 Furthermore, doctors need to perform evaluations in short periods of time and obtain the most information possible to increase not only efficacy but diagnostic efficiency. These considerations lead us to promote the use of this test, which is also helpful in planning subsequent treatment and providing guidance to families on how to care for patients. Nevertheless, a normative study of this test must be carried out in the Spanish population.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Bolló-Gasol S, Piñol-Ripoll G, Cejudo-Bolivar JC, Llorente-Vizcaino A, Peraita-Adrados H. Evaluación ecológica en el deterioro cognitivo leve y enfermedad de Alzheimer mediante el Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test. Neurología. 2014;29:339–345.