Paroxysmal painful tonic spasms (PPTS) were initially described in multiple sclerosis (MS) but they are more frequent in neuromyelitis optica (NMO). The objective is to report their presence in a series of cases of NMO and NMO spectrum disorders (NMOSD), as well as to determine their frequency and clinical features.

Patients and methodsWe conducted a retrospective assessment of medical histories of NMO/NMOSD patients treated in 2 hospitals in Buenos Aires (Hospital Durand and Hospital Álvarez) between 2009 and 2013.

ResultsOut of 15 patients with NMOSD (7 with definite NMO and 8 with limited NMO), 4 presented PPTS (26.66%). PPTS frequency in the definite NMO group was 57.14% (4/7). Of the 9 patients with longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM), 44.44% (9/15) presented PPTS. Mean age was 35 years (range, 22-38 years) and all patients were women. Mean time between NMO diagnosis and PPTS onset was 7 months (range, 1-29 months) and mean time from last relapse of LETM was 30 days (range 23-40 days). LETM (75% cervicothoracic and 25% thoracic) was observed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in all patients. Control over spasms and pain was achieved in all patients with carbamazepine (associated with gabapentin in one case). No favourable responses to pregabalin, gabapentin, or phenytoin were reported.

ConclusionsPPTS are frequent in NMO. Mean time of PPTS onset is approximately one month after an LETM relapse, with extensive cervicothoracic lesions appearing on the MRI scan. They show an excellent response to carbamazepine but little or no response to pregabalin and gabapentin. Prospective studies with larger numbers of patients are necessary in order to confirm these results.

Los espasmos tónicos paroxísticos dolorosos (ETPD) fueron descritos inicialmente en la esclerosis múltiple (EM) pero serían más frecuentes en la neuromielitis óptica (NMO). El objetivo es comunicar su presencia en una serie de casos de NMO y su espectro (NMOSD), determinar la frecuencia y las características clínicas.

Métodos y pacientesSe evaluaron retrospectivamente historias clínicas de pacientes con NMO/NMOSD en 2 centros de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires (Hospital Durand y Hospital Álvarez) durante el periodo 2009-2013.

ResultadosDe 15 pacientes con NMOSD (7 con NMO definida y 8 con NMO limitada), 4 presentaron ETPD (26,66%). En los pacientes con NMO definida la frecuencia fue del 57,14% (4/7). De 9 (9/15) pacientes con mielitis longitudinal extensa (LETM) 44,44% presentó ETPD. Edad: media 35 años (rango: 22-38 años). Cien por cien sexo femenino. Tiempo desde el diagnóstico de NMO: media 7 meses (rango: 1-29 meses) y con respecto a la última recaída de LETM: media 30 días (rango: 23-40 días). El 100% presentó LETM (cervicodorsal 75% y dorsal 25%) en resonancia magnética (RM). El 100% presentó control de los espasmos y el dolor con carbamazepina (uno asociado a gabapentin) sin una respuesta adecuada a pregabalina, gabapentin y fenitoína.

ConclusionesLos ETPD son frecuentes en la NMO. Aparecen aproximadamente al mes de una recaída de LETM con lesiones cervicodorsales extensas en RM. Tienen excelente respuesta a carbamazepina y poca o nula a pregabalina y gabapentin. Estos resultados deberán ser confirmados con estudios prospectivos con mayor número de pacientes.

Paroxysmal painful tonic spasms (PPTS) are stereotypical, recurrent, localised muscle spasms (in one or more limbs and/or the trunk) lasting around 20 to 45seconds and accompanied by intense pain and dystonia.1–7 Episodes may or may not be triggered by sudden movements or sensory stimuli and can be classified as either cerebral or spinal depending on the location of the lesion.1–7 Due to their negative impact on quality of life, rehabilitation, and daily living activities,1 PPTS should be suspected, diagnosed, and treated as soon as possible.

Although PPTS were first described by Matthews in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) in 1958,1 recently published studies suggest that they are more frequent in neuromyelitis optica (NMO),7,8 with an incidence ranging between 3% and 35%1–8 in patients with demyelinating myelopathy of different causes (MS, NMO, idiopathic).

We analysed a series of patients who met the diagnostic criteria for NMO/neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) in order to determine clinical characteristics, response to treatment, and frequency of association of PPTS with NMO and NMOSD.

Materials and methodsWe retrospectively reviewed the medical histories of all patients attending the neurology department at 2 centres in Buenos Aires (Hospital General de Agudos Dr. Carlos G. Durand and Hospital General de Agudos Dr. Teodoro Álvarez) between January 2009 and December 2013.

We included all patients with defined NMO or NMOSD with anti-aquaporin-4 (AQP4) antibodies. We used the Wingerchuk et al.9 2006 diagnostic criteria for NMO: (1) acute transverse myelitis (ATM) plus optic neuritis (ON) and (2) at least 2 of the following features: MRI findings that are normal or non-diagnostic for MS according to Barkhof and Tintoré’s criteria, MRI scan showing involvement of at least 3 spinal cord segments (longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis [LETM]), and serum positivity for NMO-IgG or AQP4 antibodies.6 Following the Wingerchuk et al.10 2007 diagnostic criteria, NMOSD included the limited forms of NMO (recurrent or simultaneous bilateral ON, single or recurrent events of LETM), optic-spinal MS, ON or LETM associated with systemic autoimmune disease, and ON or myelitis associated with brain lesions typical of NMO. Likewise, PPTS was defined as previously stated.

ResultsWe found 15 patients with NMO/NMOSD, of whom 7 had defined NMO and 8 had limited NMOSD. Three of the 8 patients with NMOSD had recurrent ON, 3 had isolated ON, and 2 had isolated LETM. Four patients in our sample had PPTS (26.66%). PPTS were detected in 57.14% (4/7) of the patients with defined NMO and none of the patients with NMOSD (0/8). Likewise, PPTS were seen in 44.44% of all patients with LETM (4/9).

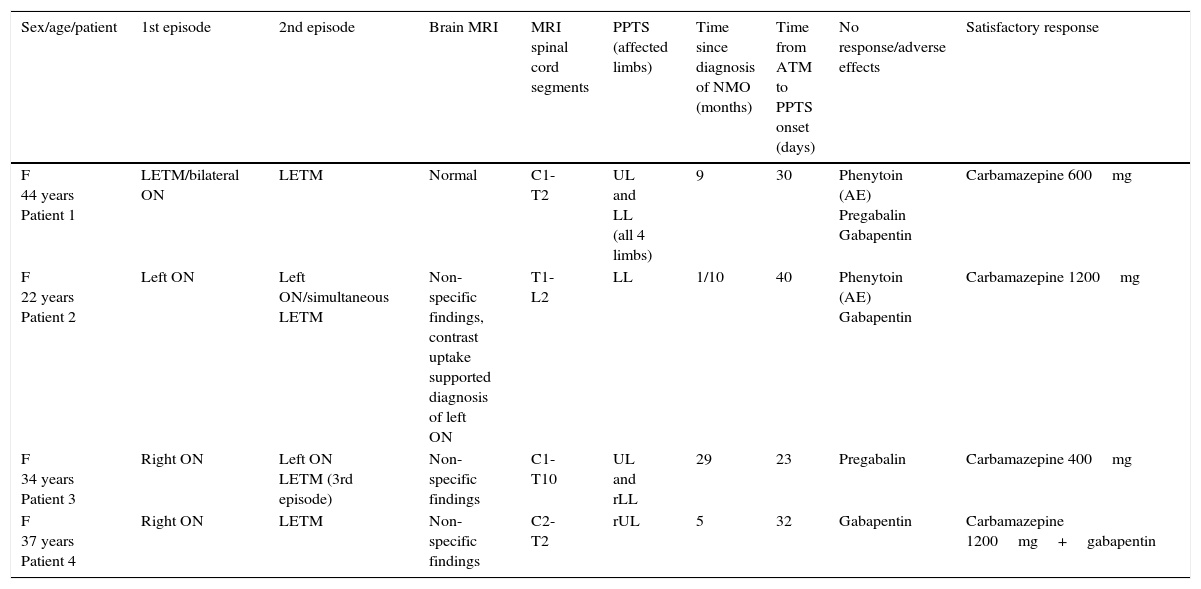

None of the patients had experienced cervicothoracic or head trauma, had a family or personal history of dystonia, or were taking anti-dopaminergic drugs (for example, neuroleptics). We will now describe the 4 reported cases of PPTS (Table 1).

Clinical, radiological, and treatment characteristics of our 4 patients with PPTS.

| Sex/age/patient | 1st episode | 2nd episode | Brain MRI | MRI spinal cord segments | PPTS (affected limbs) | Time since diagnosis of NMO (months) | Time from ATM to PPTS onset (days) | No response/adverse effects | Satisfactory response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F 44 years Patient 1 | LETM/bilateral ON | LETM | Normal | C1-T2 | UL and LL (all 4 limbs) | 9 | 30 | Phenytoin (AE) Pregabalin Gabapentin | Carbamazepine 600mg |

| F 22 years Patient 2 | Left ON | Left ON/simultaneous LETM | Non-specific findings, contrast uptake supported diagnosis of left ON | T1-L2 | LL | 1/10 | 40 | Phenytoin (AE) Gabapentin | Carbamazepine 1200mg |

| F 34 years Patient 3 | Right ON | Left ON LETM (3rd episode) | Non-specific findings | C1-T10 | UL and rLL | 29 | 23 | Pregabalin | Carbamazepine 400mg |

| F 37 years Patient 4 | Right ON | LETM | Non-specific findings | C2-T2 | rUL | 5 | 32 | Gabapentin | Carbamazepine 1200mg+gabapentin |

F: female; LETM: longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis; rLL: right lower limb; LL: lower limbs; UL: upper limbs; rUL: right upper limb; ON: optic neuritis; AE: adverse effects.

Our first patient was a 44-year-old woman with LETM and bilateral ON who was treated with IV methylprednisolone and oral corticosteroids. Treatment led to partial improvement of symptoms. However, 9 months later she experienced a relapse with severe quadriparesis and extensive cervical spinal cord lesions. Treatment with corticosteroids, azathioprine, and plasmapheresis improved her symptoms. A month later she experienced PPTS in all limbs. Although her condition improved rapidly with phenytoin, treatment had to be discontinued due to hepatotoxicity. She responded poorly to pregabalin and gabapentin. Her condition improved with carbamazepine dosed at 600mg/day but treatment was discontinued due to an increase in transaminases. She has improved slowly over the past months.

Patient 2The second patient was a 22-year-old woman with a 4-year history of left ON who experienced thoracic LETM. She improved with IV methylprednisolone, oral corticosteroids, and azathioprine. Forty days later, she presented progressive PPTS in the lower limbs. She showed no response to pregabalin and was subsequently treated with phenytoin with excellent results. However, treatment had to be discontinued due to a skin reaction. She showed no response to gabapentin. Carbamazepine 1200mg/day led to substantial improvements.

Patient 3The third patient was a 34-year-old woman with a 29-month history of right ON who developed left ON 8 months after onset of right ON. She developed cervicothoracic LETM associated with sensory alterations in the upper limbs and paraparesis in the lower limbs. She improved with IV methylprednisolone, oral corticosteroids, and azathioprine. Twenty-three days later she developed PPTS in both upper limbs and the right lower limb. She showed no response to pregabalin but improved significantly with carbamazepine 400mg/day.

Patient 4Our fourth patient was a 37-year-old woman with a 5-month history of right ON who also developed cervicothoracic LETM. Treatment with IV methylprednisolone, oral corticosteroids, and azathioprine improved her symptoms. Thirty days later, she developed PPTS in the right upper limb. In addition to gabapentin, which delivered little relief, she was also treated with carbamazepine 1200mg/day, leading to substantial improvements.

In summary, mean age in our patient sample (n=4) was 35 years (range, 22-38 years). All patients were women. Mean time elapsed from diagnosis of NMO to onset of spasms was 7 months (range, 1-29 months); mean time from the last LETM relapse was 30 days (range, 23-40 days). MRI studies showed all patients to have LETM (cervicothoracic in 75% and thoracic in 25%). Our patients developed PPTS a mean of 7 months after diagnosis (range, 1-29 months) and a mean of 30 days after an LETM relapse (range, 23-40 days). PPTS occurred after the first episode of LETM in 3 patients and after the second episode in the remaining one (patient 1). Seventy-five percent of the patients were treated with gabapentin with no response; 50% did not respond to pregabalin. Half of the patients received phenytoin and while response was good, they had to discontinue treatment due to adverse effects (skin reaction and hepatotoxicity). Carbamazepine successfully managed PPTS and pain in all patients (in association with gabapentin in one case). They all received acute treatment with IV methylprednisolone and were administered azathioprine plus oral meprednisone to prevent relapses.

DiscussionIn our study, 4 of the 15 patients with NMO/NMOSD experienced PPTS (26.66%); this percentage increases if we consider only the patients with LETM (44.44%) and it is even greater among patients with defined NMO (57.14%). In contrast, according to recent literature, fewer than 5% of the patients with MS develop PPTS.7 Studies of MS conducted in Western countries report similar figures (2%-10%).4,11 However, a study conducted in Japan revealed a higher incidence (17.18%) in patients with MS.6 These data may be misleading since a high percentage of these patients showed extensive spinal cord demyelination which might therefore correspond to optic-spinal MS, an entity which some authors include within NMOSD. These data suggest that PPTS are more frequent in NMO than in MS. In addition, a study found that pain is more severe and debilitating in patients with NMO than in those with MS.12 This may be explained by the fact that NMO, unlike MS, frequently causes transverse myelitis with severe demyelination and tissue necrosis (spinal cord) since anti-AQP4 antibodies, which belong to the IgG1 isotype, induce complement-dependent cytotoxicity. Likewise, cytokines (including IL-17, IL-8, and granulocyte colony stimulating factor) recruit neutrophils and eosinophils into perivascular spaces, where neutrophils degranulate and cause astrocyte death.4 Astrocyte loss leads to oligodendrocyte death, which in turn provokes axonal degeneration and neuronal death.12,13

It should be noted that none of our patients experienced PPTS at the onset of NMO. At disease onset, one exhibited ON associated with LETM (patient 1) whereas the remaining patients had ON exclusively. PPTS were associated with LETM relapses, occurring a mean of 30 days after the episode. In a recent study, PPTS were found to be associated with recovery from the first episode of myelitis, suggesting that partial remyelination of the spinal cord plays a major role in PPTS pathogenesis compared to demyelination caused by NMO.7 According to another recent study, presence of PPTS after the first episode of ATM is a criterion with 100% specificity and 67% sensitivity for NMO.9,14 These results suggest that occurrence of PPTS may be included in the diagnostic criteria for NMO.9

The pathophysiology of PPTS in NMO is yet to be fully understood. However, a study by Ostermann and Westerberg11 on MS and PPTS proposed that chemical mediators of inflammation (arachidonic acid, leucotrienes, and prostaglandins) lead to axonal irritation, causing PPTS. In another study, these authors suggested that early impairment of afferent fibres in the spinal cord while corticospinal fibres remain relatively intact would activate ephaptic transmission, leading to axonal diffusion within a partially demyelinated lesion in fibre tracts.4,7,11 Since PPTS are frequently bilateral, one hypothesis is that they are caused by lesions at the level of the medulla oblongata (pyramidal decussation), the spinal cord, or both.7 In our sample, 3 patients (patients 1, 3, and 4) exhibited high cervical lesions; 2 of these patients (1 and 3) showed bilateral PPTS. However, PPTS were also observed in a patient with lesions in the thoracic spinal cord (patient 2). Further studies including larger sample sizes should be conducted to confirm this hypothesis.

Regarding treatment, all 4 patients showed an excellent response to carbamazepine. Two patients responded well to phenytoin but experienced adverse effects and had to discontinue treatment. Gabapentin and pregabalin had no beneficial effects in our patient sample. These results agree with those of most published studies; however, controlled clinical trials should be conducted to confirm our findings.

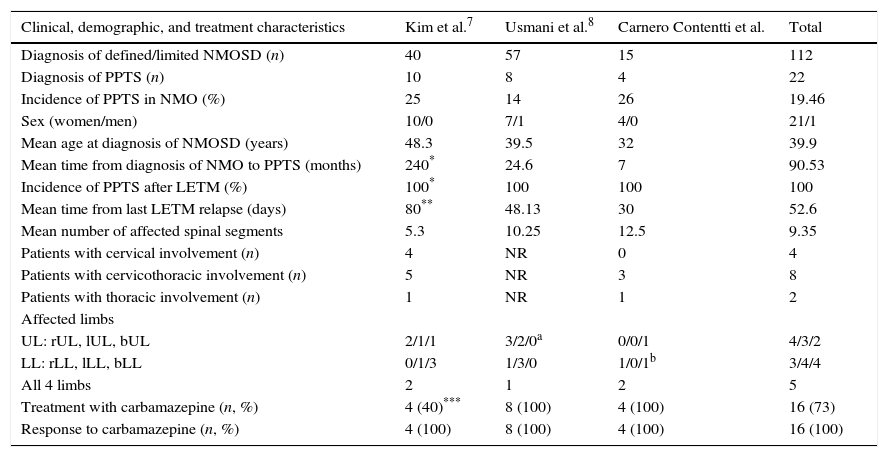

The limitations of our study include its small sample size and its retrospective design. Our results should therefore be confirmed by prospective studies with larger numbers of patients. It should be noted that few published studies (most of which are case series)3,7,8,14–16 have specifically addressed the association between NMO and PPTS and reported similar results to our own (Table 2). This observation led us to publish this study despite its small sample size.

Comparison of clinical, demographic, and treatment characteristics of 2 case series including NMO patients with PPTS and our own.

| Clinical, demographic, and treatment characteristics | Kim et al.7 | Usmani et al.8 | Carnero Contentti et al. | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis of defined/limited NMOSD (n) | 40 | 57 | 15 | 112 |

| Diagnosis of PPTS (n) | 10 | 8 | 4 | 22 |

| Incidence of PPTS in NMO (%) | 25 | 14 | 26 | 19.46 |

| Sex (women/men) | 10/0 | 7/1 | 4/0 | 21/1 |

| Mean age at diagnosis of NMOSD (years) | 48.3 | 39.5 | 32 | 39.9 |

| Mean time from diagnosis of NMO to PPTS (months) | 240* | 24.6 | 7 | 90.53 |

| Incidence of PPTS after LETM (%) | 100* | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Mean time from last LETM relapse (days) | 80** | 48.13 | 30 | 52.6 |

| Mean number of affected spinal segments | 5.3 | 10.25 | 12.5 | 9.35 |

| Patients with cervical involvement (n) | 4 | NR | 0 | 4 |

| Patients with cervicothoracic involvement (n) | 5 | NR | 3 | 8 |

| Patients with thoracic involvement (n) | 1 | NR | 1 | 2 |

| Affected limbs | ||||

| UL: rUL, lUL, bUL | 2/1/1 | 3/2/0a | 0/0/1 | 4/3/2 |

| LL: rLL, lLL, bLL | 0/1/3 | 1/3/0 | 1/0/1b | 3/4/4 |

| All 4 limbs | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Treatment with carbamazepine (n, %) | 4 (40)*** | 8 (100) | 4 (100) | 16 (73) |

| Response to carbamazepine (n, %) | 4 (100) | 8 (100) | 4 (100) | 16 (100) |

bLL: both lower limbs; bUL: both upper limbs; PPTS: paroxysmal painful tonic spasms; LETM: longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis; rLL: right lower limb; lLL: left lower limb; LL: lower limbs; UL: upper limbs; rUL: right upper limb; lUL: left upper limb; n: number; NMOSD: neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder; NR: not reported.

One patient presented PPTS and NMO simultaneously; patient 2 experienced PPTS 4490 days after diagnosis of NMO, and patient 4, 1963 days after diagnosis of NMO. For this reason, the mean time from diagnosis of NMO to PPTS was 240 months. If we excluded the outliers, mean time would be 25.5 months (80% of the sample).

90% of the episodes of PPTS occurred within the first 80 days after the first episode of myelitis. PPTS occurred a mean of 48.13 days after the first episode of LETM (8 out of 10 patients, 80%).

40% of the patients were treated with phenytoin (10% of these in combination with carbamazepine), 20% with gabapentin, and 10% with baclofen and showed good response.

PPTS are frequent in patients with NMO (57.14% in our series). Although first described in MS, they are less common in this disease than in NMO (<10%). In our sample, none of the patients with NMOSD showed this association since these patients mainly had ON (either isolated or recurrent). PPTS generally appear a month after a myelitis relapse and are associated with extensive cervicothoracic lesions in MRI. They should not be regarded as a manifestation of disease relapse but rather as a paroxysmal symptom that should be recognised and treated to minimise their impact on patients’ quality of life. Pregabalin and gabapentin have little to no effect on PPTS whereas carbamazepine achieves excellent results and should therefore be considered the treatment of choice.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Carnero Contentti E, Leguizamón F, Hryb JP, Celso J, Di Pace JL, Ferrari J, et al. Neuromielitis óptica: asociación con espasmos tónicos paroxísticos dolorosos. Neurología. 2016;31:511–515.