Mobile health or mHealth, defined as the provision of health information or healthcare by means of mobile devices or tablets, is emerging as a major game-changer for patients, care providers, and investors. An app is a programme with special characteristics installed on a small mobile device, either a tablet or smartphone, with which the user interacts via a touch-based interface. The purpose of the app is to facilitate completion of a certain task or assist with daily activities.

ObjectiveThe aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review of published information on apps directed at the field of neurorehabilitation, in order to classify them and describe their main characteristics.

Material and methodsA systematic review was carried out by means of a literature search in biomedical databases and other information sources related to mobile applications. Apps were classified into five categories: health habits, information, assessment, treatment, and specific uses.

ConclusionsThere are numerous applications with potential for use in the field of neurorehabilitation, so it is important that developers and designers understand the needs of people with neurological disorders so that their products will be valid and effective in light of those needs. Similarly, professionals, patients, families, and caregivers should have clear criteria and indicators to help them select the best applications for their specific situations.

La mHealth, definida como la prestación de información o asistencia sanitaria a través del uso de dispositivos móviles o tabletas, se postula como una de las grandes apuestas para pacientes, proveedores e inversores. Una app es un programa, con unas características especiales, que se instala en un dispositivo móvil, ya sea tableta digital o teléfono inteligente, y que suele tener un tamaño reducido, y cuyo objetivo es facilitar la consecución de una tarea determinada o asistir en gestiones diarias, siendo el modo de interacción entre el usuario y la aplicación el tacto.

ObjetivoEl objetivo del presente trabajo fue realizar una revisión sistemática acerca de la información publicada sobre las apps enfocadas al campo de la neurorrehabilitación, con el fin de clasificarlas y llevar a cabo una descripción de las principales características de las mismas.

Material y métodosSe realiza una revisión sistemática mediante búsqueda bibliográfica en bases de datos biomédicas, así como en otras fuentes de información propias del ámbito de las aplicaciones tipo apps. Se clasificaron las apps en 5 categorías: hábitos saludables, informativas, valoración, tratamiento y específicas.

ConclusionesExiste gran cantidad de apps con potencial uso en el campo de la neurorrehabilitación, por lo que es importante que los desarrolladores y diseñadores apps conozcan cuáles son las necesidades de la población con patología neurológica para que sus productos sean válidos y eficaces en dicho contexto. Del mismo modo, los profesionales, pacientes, familiares y cuidadores deberían disponer de criterios claros e indicadores que pudieran ayudarles a seleccionar las aplicaciones óptimas para sus necesidades concretas.

According to a report published by the World Health Organisation (WHO) in 2006 under the title ‘Neurological disorders: public health challenges’, neurological disorders affect approximately one billion people worldwide, regardless of sex, education level, or income level.1 This report also states that in Europe, the costs associated with neurological diseases amounted to €139 billion in 2004; these disorders contribute to 6.29% of total disability-adjusted life years (DALY), that is, the sum of years of potential life lost due to premature mortality and the years of productive life lost due to disability. Population increases and ageing have resulted in greater costs and higher percentages of DALYs. Health systems are therefore treating increasing numbers of people with different disorders which may result in disability but not necessarily in mortality, as indicated by the Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study.2,3 The prevalence of neurological diseases is estimated to reach 1136 million people by 2030. In Spain, between 13% and 16% of the population has some type of neurological disorder and nearly one and a half million people have a severe neurological disease.1

Democratisation of information via the Internet and other related tools is one of the main advances of humankind in recent times. Information and communications technologies (ICT) are increasingly being used in healthcare, which changes traditional patient management strategies. These changes will be more marked in the future due to the impact of these technologies on the demand for physicians, and especially because of the possibilities they offer in the care and follow-up for patients with neurological or related disorders.4,5

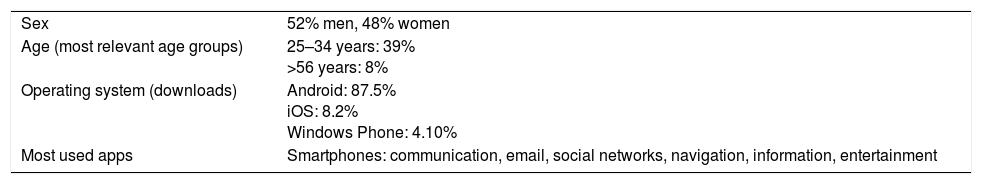

Thanks to these technologies, the healthcare sector can provide more personalised, participatory, and preventive services. The use of ICT for healthcare has been termed ‘eHealth’. In this context, mHealth (the use of mobile devices to provide healthcare and information to consumers) is a groundbreaking initiative for patients, healthcare providers, and investors. Mobile applications, or apps, are a promising tool in healthcare as they provide new perspectives for patients and health professionals alike.6,7 Mobile apps are programmes developed to run on mobile devices (tablets, smartphones, etc.); they are normally adapted to the device's processor specifications and storage capacity.8 The purpose of an app is to assist in achieving a specific goal or aid in daily activities9; interaction between the app and the user is touch-based. From a healthcare viewpoint, the potential goals of apps include patient empowerment (fostering an individual's ability to make decisions and manage his or her own life; the WHO considers this term essential for health promotion), changing the lifestyle habits, changing relationships and processes, and intelligent data storage and monitoring.4 The profile of Spanish app users is shown in Table 1.

Profile of app users in Spain, 2014.

| Sex | 52% men, 48% women |

| Age (most relevant age groups) | 25–34 years: 39% >56 years: 8% |

| Operating system (downloads) | Android: 87.5% iOS: 8.2% Windows Phone: 4.10% |

| Most used apps | Smartphones: communication, email, social networks, navigation, information, entertainment |

Adapted from The App Date (2014): 5° informe estado de las apps en España.30

Since smartphones became popular, numerous health-related apps have been developed for professionals, patients, and the general population. According to the latest study by the Institute for Healthcare Informatics, the Apple App Store in Spain offers around 40000 health-related apps for iPhone and iPad. Together, mobile app stores offer a total of 97000 health-related apps, a large proportion of which are offered by Google Play. Health is the third fastest growing app category after games and general apps. The number of health-related apps is expected to increase at a rate of 23% per year over the following 5 years.10

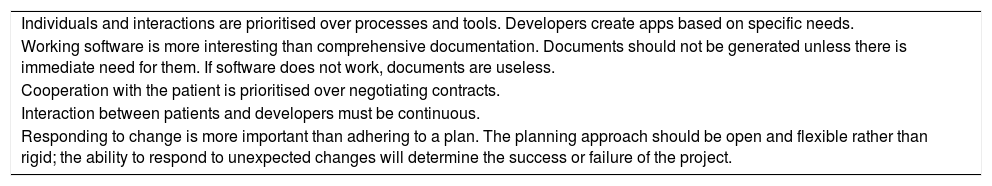

According to estimates presented at MEDICA 2012, a trade fair for the medical industry which was held in Dusseldorf (Germany), the mobile app sector would have 500 million clients in 2015, and the rate of growth in that market would be 800%.10,11 A recent report requested by the Global System for Mobile Communications Association and prepared by PriceWaterhouseCoopers (now PwC) highlighted the potential socioeconomic impact of mHealth and estimated that electronic systems could save approximately €10 billion between 2012 and 2017.7 In view of the astounding increase in the number of health-related apps on the market, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Union are working towards establishing quality criteria for these apps (Table 2).12,13 This also applies to mobile apps potentially used in or specifically designed for neurorehabilitation. To date, no studies have evaluated these apps to classify them by purpose, validity, or target population.

Quality criteria for health-related apps.

| Individuals and interactions are prioritised over processes and tools. Developers create apps based on specific needs. |

| Working software is more interesting than comprehensive documentation. Documents should not be generated unless there is immediate need for them. If software does not work, documents are useless. |

| Cooperation with the patient is prioritised over negotiating contracts. |

| Interaction between patients and developers must be continuous. |

| Responding to change is more important than adhering to a plan. The planning approach should be open and flexible rather than rigid; the ability to respond to unexpected changes will determine the success or failure of the project. |

Adapted from a report by the FDA13 and from Blanco P, Camarero J, Fumero A, Werterski A, Rodríguez P. Metodología de desarrollo ágil para sistemas móviles: introducción al desarrollo con Android y el iPhone. Madrid: Universidad Politécnica de Madrid; 2009.

The purpose of this study is to conduct a systematic review of articles addressing apps developed for neurorehabilitation in order to classify them and describe their characteristics. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to analyse literature on the topic.

As a secondary objective, we aim to summarise the therapeutic potential of each of these apps for neurorehabilitation by analysing their functions, objectives, and technical characteristics.

Material and methodsWe conducted a literature search on biomedical databases and other information sources for apps.

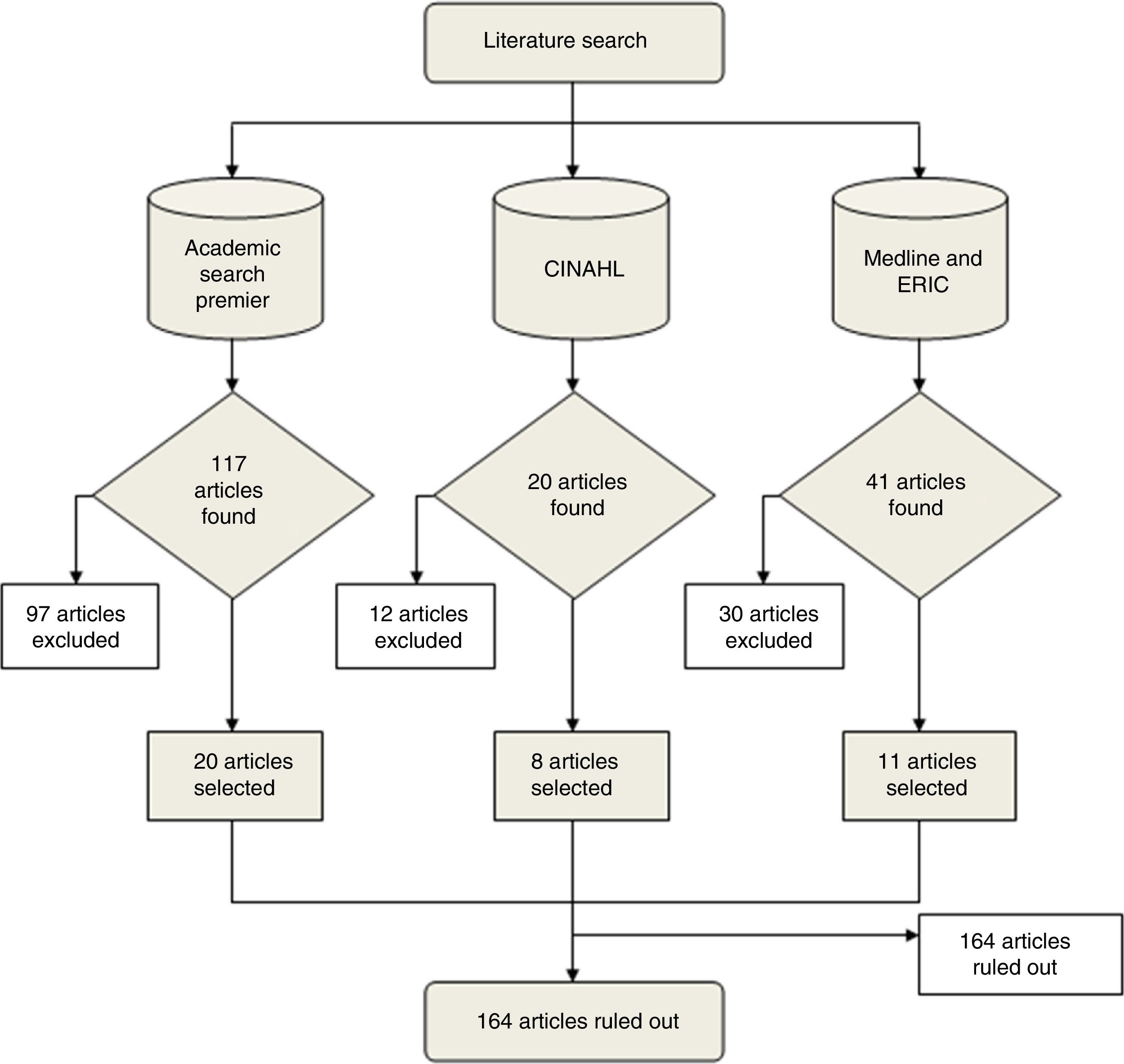

Database literature searchThis systematic review included studies addressing the use of apps in neurorehabilitation. We searched the databases Academic Search Premier, CINAHL, Medline, and ERIC using the following keywords: ‘apps’, ‘rehabilitation’, ‘smartphones’, ‘iPhones’, and ‘iPads’. We included all articles published in English, Spanish, or French between 2000 and February 2015 (2000 is the benchmark for the proliferation and normalisation of health-related tools in society).5 We excluded those studies not addressing apps specific for neurorehabilitation and studies published before 2000 or in other languages than those listed above.

Search in other information sourcesWe searched for apps in specific information sources and classified them using the following 3-stage process:

- (1)

First stage. Between November 2014 and February 2015 we searched for apps for neurorehabilitation. In this stage we included all apps regardless of the language and the country of development. Our research group, which includes specialists in neurorehabilitation, used the main app stores, published reports on health-related apps, app databases, social networks, and news on the mass media. We considered the main operating systems: iOS, Android, BlackBerry, Symbian, and Windows Phone.

- (2)

Second stage. We analysed the identified apps and selected those expressly designed or potentially useful for neurorehabilitation based on the following criteria: therapeutic utility, content, quality, design, user experience, recognition, and awards (if applicable).

- (3)

Third stage. We classified the included apps. As stated in a report on the 50 best health-related apps in Spanish,5 there is no consensus on how to classify apps and each study uses the classification system that best suits its purposes. Our study classified apps in 5 categories based on the type of use and function in neurorehabilitation:

- –

Healthy lifestyle. Apps focusing on improving the patients’ lifestyle by promoting a healthy and balanced diet, adequate hydration, and regular exercise. Although our study addresses neurorehabilitation, these apps were included in the first phase since they complement basic healthcare.

- –

Information. These apps provide complete and detailed data on a specific condition or other medical topics. We did not evaluate the format (whether the app included text, images, or videos).

- –

Assessment. Apps assisting in the diagnosis, assessment, and/or follow-up of patients by providing data for healthcare professionals.

- –

Treatment. This category contains apps that can be used by healthcare professionals to treat patients with neurological disorders. They can be further classified depending on their purpose (physical, cognitive, or speech therapy).

- –

Specific. These apps have been designed by neurorehabilitation teams or units to address specific disorders, based on the team's own criteria or needs. They promote the education and participation of patients and their families by providing relevant data on treatment and home assistance, as well as how to find self-help groups, healthcare professionals, etc.

The articles collected in the literature search were evaluated on the Jadad scale (also known as the Oxford quality scoring system).14 The Jadad scale is a simple and quick-to-administer validated questionnaire which independently assesses the methodological quality of a clinical trial. This scale evaluates randomisation, blinding of patients and raters (double-blind), and withdrawal and drop-out rates. Results are shown on a 5-point scale, with higher scores indicating higher methodological quality. Clinical trials scoring 5 points are regarded as very rigorous whereas those scoring fewer than 3 points are considered to have a poor methodological quality. We administered the Jadad scale to assess the methodological quality of each article in order to make sure that data were supported by good methodology, rather than to evaluate the validity or technical quality of the app itself. The apps mentioned in the studies yielded by the literature search were also classified in the 5 categories mentioned above.

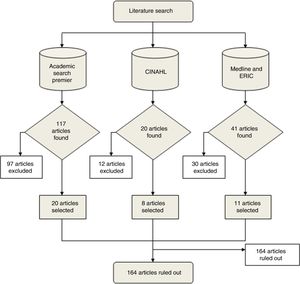

ResultsDatabase literature searchWe initially identified 178 studies, 139 of which were excluded according to our criteria. After a more thorough evaluation, only 14 of the remaining 39 studies15–28 were definitively included. Fig. 1 is a flow chart showing the number of studies identified in each database and the number of studies excluded.

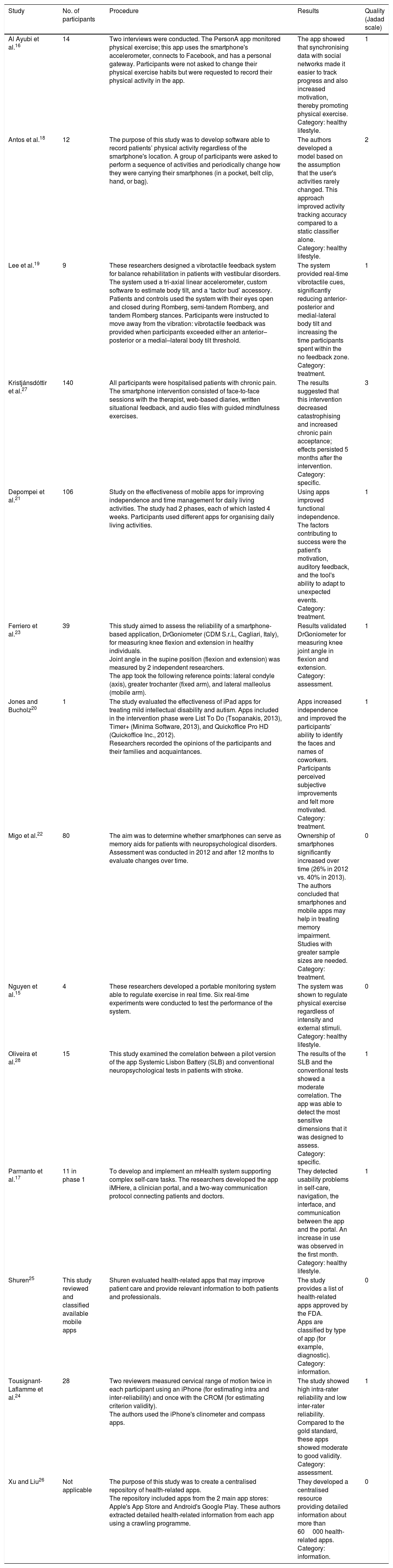

The studies included in this review were highly heterogeneous (Table 3): 4 studies15–18 focused on apps for monitoring healthy habits, physical exercise, and self-care; 4 studies assessed the usefulness of certain apps for improving balance,19 independence,20,21 and memory22; 2 studies assessed the reliability of apps as measuring tools23,24 and 2 studies focused on developing a repository of health-related apps25,26; and the 2 remaining studies contained more specific information: one studied an app that improved communication between patients and therapists27 and the other compared mHealth to traditional medicine.28

Participants, intervention, results, and quality of the included studies.

| Study | No. of participants | Procedure | Results | Quality (Jadad scale) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al Ayubi et al.16 | 14 | Two interviews were conducted. The PersonA app monitored physical exercise; this app uses the smartphone's accelerometer, connects to Facebook, and has a personal gateway. Participants were not asked to change their physical exercise habits but were requested to record their physical activity in the app. | The app showed that synchronising data with social networks made it easier to track progress and also increased motivation, thereby promoting physical exercise. Category: healthy lifestyle. | 1 |

| Antos et al.18 | 12 | The purpose of this study was to develop software able to record patients’ physical activity regardless of the smartphone's location. A group of participants were asked to perform a sequence of activities and periodically change how they were carrying their smartphones (in a pocket, belt clip, hand, or bag). | The authors developed a model based on the assumption that the user's activities rarely changed. This approach improved activity tracking accuracy compared to a static classifier alone. Category: healthy lifestyle. | 2 |

| Lee et al.19 | 9 | These researchers designed a vibrotactile feedback system for balance rehabilitation in patients with vestibular disorders. The system used a tri-axial linear accelerometer, custom software to estimate body tilt, and a ‘tactor bud’ accessory. Patients and controls used the system with their eyes open and closed during Romberg, semi-tandem Romberg, and tandem Romberg stances. Participants were instructed to move away from the vibration: vibrotactile feedback was provided when participants exceeded either an anterior–posterior or a medial–lateral body tilt threshold. | The system provided real-time vibrotactile cues, significantly reducing anterior-posterior and medial-lateral body tilt and increasing the time participants spent within the no feedback zone. Category: treatment. | 1 |

| Kristjánsdóttir et al.27 | 140 | All participants were hospitalised patients with chronic pain. The smartphone intervention consisted of face-to-face sessions with the therapist, web-based diaries, written situational feedback, and audio files with guided mindfulness exercises. | The results suggested that this intervention decreased catastrophising and increased chronic pain acceptance; effects persisted 5 months after the intervention. Category: specific. | 3 |

| Depompei et al.21 | 106 | Study on the effectiveness of mobile apps for improving independence and time management for daily living activities. The study had 2 phases, each of which lasted 4 weeks. Participants used different apps for organising daily living activities. | Using apps improved functional independence. The factors contributing to success were the patient's motivation, auditory feedback, and the tool's ability to adapt to unexpected events. Category: treatment. | 1 |

| Ferriero et al.23 | 39 | This study aimed to assess the reliability of a smartphone-based application, DrGoniometer (CDM S.r.L, Cagliari, Italy), for measuring knee flexion and extension in healthy individuals. Joint angle in the supine position (flexion and extension) was measured by 2 independent researchers. The app took the following reference points: lateral condyle (axis), greater trochanter (fixed arm), and lateral malleolus (mobile arm). | Results validated DrGoniometer for measuring knee joint angle in flexion and extension. Category: assessment. | 1 |

| Jones and Bucholz20 | 1 | The study evaluated the effectiveness of iPad apps for treating mild intellectual disability and autism. Apps included in the intervention phase were List To Do (Tsopanakis, 2013), Timer+ (Minima Software, 2013), and Quickoffice Pro HD (Quickoffice Inc., 2012). Researchers recorded the opinions of the participants and their families and acquaintances. | Apps increased independence and improved the participants’ ability to identify the faces and names of coworkers. Participants perceived subjective improvements and felt more motivated. Category: treatment. | 1 |

| Migo et al.22 | 80 | The aim was to determine whether smartphones can serve as memory aids for patients with neuropsychological disorders. Assessment was conducted in 2012 and after 12 months to evaluate changes over time. | Ownership of smartphones significantly increased over time (26% in 2012 vs. 40% in 2013). The authors concluded that smartphones and mobile apps may help in treating memory impairment. Studies with greater sample sizes are needed. Category: treatment. | 0 |

| Nguyen et al.15 | 4 | These researchers developed a portable monitoring system able to regulate exercise in real time. Six real-time experiments were conducted to test the performance of the system. | The system was shown to regulate physical exercise regardless of intensity and external stimuli. Category: healthy lifestyle. | 0 |

| Oliveira et al.28 | 15 | This study examined the correlation between a pilot version of the app Systemic Lisbon Battery (SLB) and conventional neuropsychological tests in patients with stroke. | The results of the SLB and the conventional tests showed a moderate correlation. The app was able to detect the most sensitive dimensions that it was designed to assess. Category: specific. | 1 |

| Parmanto et al.17 | 11 in phase 1 | To develop and implement an mHealth system supporting complex self-care tasks. The researchers developed the app iMHere, a clinician portal, and a two-way communication protocol connecting patients and doctors. | They detected usability problems in self-care, navigation, the interface, and communication between the app and the portal. An increase in use was observed in the first month. Category: healthy lifestyle. | 1 |

| Shuren25 | This study reviewed and classified available mobile apps | Shuren evaluated health-related apps that may improve patient care and provide relevant information to both patients and professionals. | The study provides a list of health-related apps approved by the FDA. Apps are classified by type of app (for example, diagnostic). Category: information. | 0 |

| Tousignant-Laflamme et al.24 | 28 | Two reviewers measured cervical range of motion twice in each participant using an iPhone (for estimating intra and inter-reliability) and once with the CROM (for estimating criterion validity). The authors used the iPhone's clinometer and compass apps. | The study showed high intra-rater reliability and low inter-rater reliability. Compared to the gold standard, these apps showed moderate to good validity. Category: assessment. | 1 |

| Xu and Liu26 | Not applicable | The purpose of this study was to create a centralised repository of health-related apps. The repository included apps from the 2 main app stores: Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play. These authors extracted detailed health-related information from each app using a crawling programme. | They developed a centralised resource providing detailed information about more than 60000 health-related apps. Category: information. | 0 |

With all of the above in mind, apps were classified as follows: 4 in ‘healthy lifestyle’,15–18 2 in ‘information’,25,26 2 in ‘assessment’,23,24 4 in ‘treatment’,19–22 and 2 in ‘specific’.27,28

Table 3 shows Jadad scores for each of the studies included in this review. In general terms, the methodological quality of the studies was poor. Four articles15,22,25,26 scored 0 points on the Jadad scale, eight scored 1,16,17,19–21,23,24,28 one scored 2,18 and the remaining one scored 3.27 These low scores were due to lack of randomisation or to studies not describing the blinding method.

Searches of other information sourcesA total of 323 apps met the inclusion criteria during the first stage.

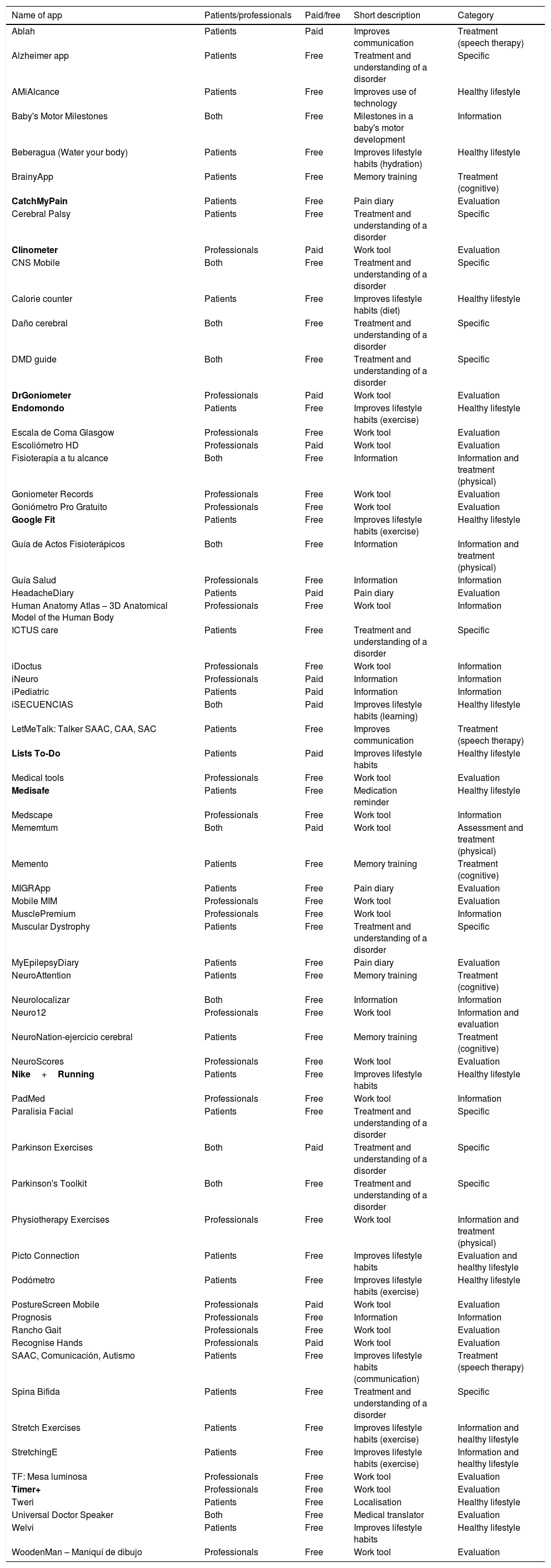

In the second stage, 69 apps were selected. Table 4 provides the names of these apps and the ones found using the literature search, indicates whether they are for use by patients or professionals and whether or not they are free, and provides a short description of each.

List of apps with potential uses in neurorehabilitation.

| Name of app | Patients/professionals | Paid/free | Short description | Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ablah | Patients | Paid | Improves communication | Treatment (speech therapy) |

| Alzheimer app | Patients | Free | Treatment and understanding of a disorder | Specific |

| AMiAlcance | Patients | Free | Improves use of technology | Healthy lifestyle |

| Baby's Motor Milestones | Both | Free | Milestones in a baby's motor development | Information |

| Beberagua (Water your body) | Patients | Free | Improves lifestyle habits (hydration) | Healthy lifestyle |

| BrainyApp | Patients | Free | Memory training | Treatment (cognitive) |

| CatchMyPain | Patients | Free | Pain diary | Evaluation |

| Cerebral Palsy | Patients | Free | Treatment and understanding of a disorder | Specific |

| Clinometer | Professionals | Paid | Work tool | Evaluation |

| CNS Mobile | Both | Free | Treatment and understanding of a disorder | Specific |

| Calorie counter | Patients | Free | Improves lifestyle habits (diet) | Healthy lifestyle |

| Daño cerebral | Both | Free | Treatment and understanding of a disorder | Specific |

| DMD guide | Both | Free | Treatment and understanding of a disorder | Specific |

| DrGoniometer | Professionals | Paid | Work tool | Evaluation |

| Endomondo | Patients | Free | Improves lifestyle habits (exercise) | Healthy lifestyle |

| Escala de Coma Glasgow | Professionals | Free | Work tool | Evaluation |

| Escoliómetro HD | Professionals | Paid | Work tool | Evaluation |

| Fisioterapia a tu alcance | Both | Free | Information | Information and treatment (physical) |

| Goniometer Records | Professionals | Free | Work tool | Evaluation |

| Goniómetro Pro Gratuito | Professionals | Free | Work tool | Evaluation |

| Google Fit | Patients | Free | Improves lifestyle habits (exercise) | Healthy lifestyle |

| Guía de Actos Fisioterápicos | Both | Free | Information | Information and treatment (physical) |

| Guía Salud | Professionals | Free | Information | Information |

| HeadacheDiary | Patients | Paid | Pain diary | Evaluation |

| Human Anatomy Atlas – 3D Anatomical Model of the Human Body | Professionals | Free | Work tool | Information |

| ICTUS care | Patients | Free | Treatment and understanding of a disorder | Specific |

| iDoctus | Professionals | Free | Work tool | Information |

| iNeuro | Professionals | Paid | Information | Information |

| iPediatric | Patients | Paid | Information | Information |

| iSECUENCIAS | Both | Paid | Improves lifestyle habits (learning) | Healthy lifestyle |

| LetMeTalk: Talker SAAC, CAA, SAC | Patients | Free | Improves communication | Treatment (speech therapy) |

| Lists To-Do | Patients | Paid | Improves lifestyle habits | Healthy lifestyle |

| Medical tools | Professionals | Free | Work tool | Evaluation |

| Medisafe | Patients | Free | Medication reminder | Healthy lifestyle |

| Medscape | Professionals | Free | Work tool | Information |

| Mememtum | Both | Paid | Work tool | Assessment and treatment (physical) |

| Memento | Patients | Free | Memory training | Treatment (cognitive) |

| MIGRApp | Patients | Free | Pain diary | Evaluation |

| Mobile MIM | Professionals | Free | Work tool | Evaluation |

| MusclePremium | Professionals | Free | Work tool | Information |

| Muscular Dystrophy | Patients | Free | Treatment and understanding of a disorder | Specific |

| MyEpilepsyDiary | Patients | Free | Pain diary | Evaluation |

| NeuroAttention | Patients | Free | Memory training | Treatment (cognitive) |

| Neurolocalizar | Both | Free | Information | Information |

| Neuro12 | Professionals | Free | Work tool | Information and evaluation |

| NeuroNation-ejercicio cerebral | Patients | Free | Memory training | Treatment (cognitive) |

| NeuroScores | Professionals | Free | Work tool | Evaluation |

| Nike+Running | Patients | Free | Improves lifestyle habits | Healthy lifestyle |

| PadMed | Professionals | Free | Work tool | Information |

| Paralisia Facial | Patients | Free | Treatment and understanding of a disorder | Specific |

| Parkinson Exercises | Both | Paid | Treatment and understanding of a disorder | Specific |

| Parkinson's Toolkit | Both | Free | Treatment and understanding of a disorder | Specific |

| Physiotherapy Exercises | Professionals | Free | Work tool | Information and treatment (physical) |

| Picto Connection | Patients | Free | Improves lifestyle habits | Evaluation and healthy lifestyle |

| Podómetro | Patients | Free | Improves lifestyle habits (exercise) | Healthy lifestyle |

| PostureScreen Mobile | Professionals | Paid | Work tool | Evaluation |

| Prognosis | Professionals | Free | Information | Information |

| Rancho Gait | Professionals | Free | Work tool | Evaluation |

| Recognise Hands | Professionals | Paid | Work tool | Evaluation |

| SAAC, Comunicación, Autismo | Patients | Free | Improves lifestyle habits (communication) | Treatment (speech therapy) |

| Spina Bifida | Patients | Free | Treatment and understanding of a disorder | Specific |

| Stretch Exercises | Patients | Free | Improves lifestyle habits (exercise) | Information and healthy lifestyle |

| StretchingE | Patients | Free | Improves lifestyle habits (exercise) | Information and healthy lifestyle |

| TF: Mesa luminosa | Professionals | Free | Work tool | Evaluation |

| Timer+ | Professionals | Free | Work tool | Evaluation |

| Tweri | Patients | Free | Localisation | Healthy lifestyle |

| Universal Doctor Speaker | Both | Free | Medical translator | Evaluation |

| Welvi | Patients | Free | Improves lifestyle habits | Healthy lifestyle |

| WoodenMan – Maniquí de dibujo | Professionals | Free | Work tool | Evaluation |

Apps in bold were identified in the literature search in databases.

All other apps were identified using alternative information sources.

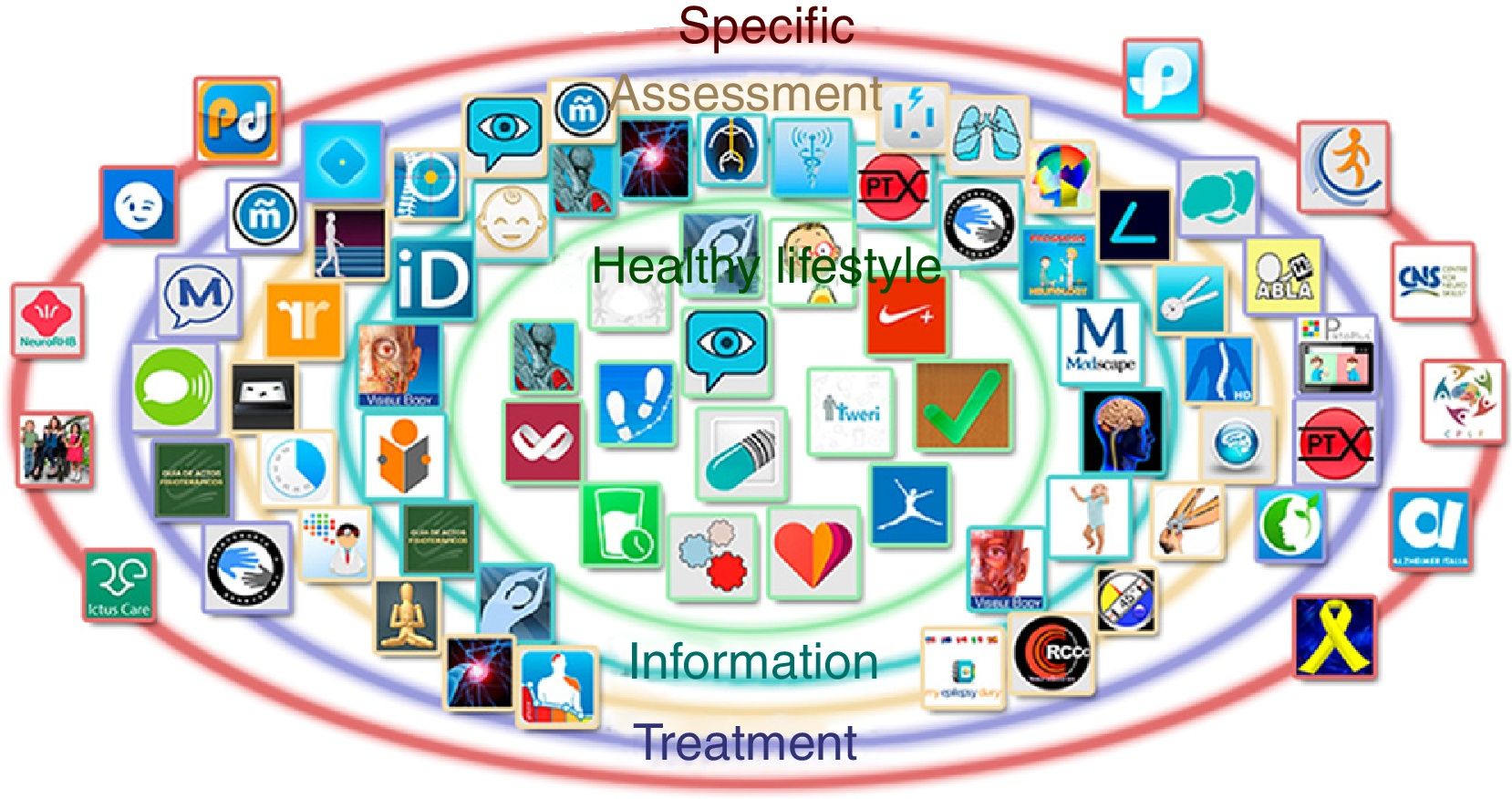

In the third stage of the study, the apps were classified as shown in Fig. 2 and the right column of Table 4: 15 apps focused on healthy lifestyle, 17 apps provided information, 23 apps assisted in assessment, 11 apps focused on treatment (4 for physical and cognitive treatment, and 3 for speech therapy), and 11 apps were specifically meant for neurorehabilitation. We must be mindful that the same app may meet criteria for multiple categories.

Regarding the type of consumer they target, 32 apps were for patients, 25 for healthcare professionals, and 12 for both groups. Lastly, 13 apps were available for a fee and the remaining 56 were free.

DiscussionAt present, more than half of all Spanish residents older than 18 have smartphones. In fact, using a smartphone to access the Internet is leading to a decrease in Internet access by computer.29 Smartphones and tablets are well regarded among users due to their portability. Current mobile devices offer multitouch interfaces and a wide range of functions (camera, videocamera, text messages, geolocation, etc.), feature large screens, and provide the possibility of voice control.8

In Spain, nearly 4 million apps per day were downloaded to mobile devices in 2014, compared to the 2.7 million apps downloaded per day in 2012. According to a recent report,30 there were 23 million active users of apps in Spain in 2014 compared to 12 million in 2012. These figures suggest that health-related apps are a potentially useful resource in a technology-savvy population that includes patients with neurological diseases.

In Spain, as in other countries, Internet and mobile apps are the main route of access to medical information.29 Apps are also useful for healthcare professionals, allowing them to receive further training, look up for information, contact other professionals, transmit information, and promote healthy practices. Use of these agile, powerful, easy-to-use tools is now practically ubiquitous. Several apps included in this review are intended to provide medical information (for example, Guía salud, iNeuro, and iPediatric) or facilitate communication with healthcare professionals (for example, Neurolocalizar); these aims may improve treatment adherence and patient engagement.

Apps are invaluable tools for healthcare professionals; some experts even consider them one of the greatest technological advances of our time.7 This paradigm shift also affects professionals in the field of neurorehabilitation. Many neurorehabilitation experts are now using new technologies for their treatments. However, it is also true that these technologies are less effective than expected since they were not specifically designed for a given intervention, unlike some mobile apps.31 However, given the increasing number of apps on the market, it is difficult to determine which ones are useful and best meet the needs of patients with neurological diseases. We therefore need documents or guidelines to help us decide which apps are the most useful, as recommended by the APP report.30 The purpose of our study was to provide a general perspective on the apps used in neurorehabilitation to help healthcare professionals identify the most useful new tools in this field based on the patients’ needs.

To our knowledge, no previous studies have analysed and classified the apps that are potentially useful for neurorehabilitation. Xu and Liu26 created a repository of health-related apps distributed by the Apple App Store and Google Play Store and gathered detailed data about a total of 60000 apps. In contrast, our purpose was to identify apps specifically designed for neurorehabilitation by conducting a systematic literature search and using other information sources provided by mobile apps themselves. We identified 15 apps promoting healthy lifestyle, 17 apps providing medical information, 23 apps for assessment, 11 apps addressing treatment, and 11 apps specifically intended for neurorehabilitation. Thirty-two apps were targeted towards patients, 25 towards healthcare professionals, and 12 to both profiles. Thirteen apps were fee-based and 56 were free.

There is a wide range of apps promoting a healthy lifestyle; these apps can be synchronised with other devices, they are easy to use, and they provide patients with an independent source of health information.8,32–37 Patient associations seem to agree that quality seals should be used to indicate which apps are reliable; one example is the AppSaludable Quality Seal, the first Spanish seal that recognises quality and safety of health-related apps.34 ‘Endomondo’, ‘Google Fit’, and ‘AMiAlcance’ are especially noteworthy apps due to the wide range of functions they offer. Informative apps usually focus on providing information to patients and establishing clinical guidelines; examples include ‘Fisioterapia a tu alcance’ and ‘iNeuro’. Assessment apps are the most numerous, but they will require studies to demonstrate their validity and reliability in neurorehabilitation. We recommend ‘Goniometer Pro’, ‘DrGoniometer’, and especially ‘Rancho Gait’, an app which evaluates normal and pathological gait and suggests support devices according to the needs it detects. Few apps have been specifically designed for neurorehabilitation. We would like to highlight ‘Mementum’, which was designed for patients with Parkinson's disease, ‘Physiotherapy Exercises’, a repository of 950 exercises for rehabilitating neurological patients, and ‘NeuroRHB – Daño Cerebral’ and ‘IctusCare’, 2 apps specifically focusing on awareness, assessment, and treatment in the brain injury unit setting.

According to the data yielded by the literature search, healthy lifestyle apps focused on promoting or recording physical exercise seem to be effective and have positive results regardless of exercise intensity.15–18 Apps with a two-way communication protocol connecting patients with their doctors promote adherence, allow for prolonged follow-up,17 and reduce pain catastrophising.27 The apps with the greatest impact on the lives of patients and caregivers are those promoting independence,20,21 those using vibrotactile feedback for balance rehabilitation,19 those focusing on memory, and those used for neuropsychological interventions.22,28 Cerrito et al.35 developed an app for quantifying sit-to-stand movement in healthy elderly patients which was found to be reliable and valid. Lastly, 2 of the included studies estimated the reliability of apps measuring the range of motion in joints23,24; one of these uses an inclinometer whereas the other uses a goniometer. This is a promising area for app developers. However, our results should be interpreted with caution due to the low methodological quality of the studies identified by our search.

Aware of the wide range of potential functions of mobile apps, the increasing innovation in the field, and the potential benefits and risks for public health, the FDA has published a document to inform manufacturers, distributors, and other entities about how they intended to regulate apps36 in order to provide oversight in terms of safety and effectiveness.37,38 Some authors12,25 are requesting that the FDA publish a list of approved medical apps. As for the apps included in this study, we need validation studies in target populations and approval of these data by control agencies, based on the patients’ needs. Meulendijk et al.39 explored the essential requirements for health-related apps from the patients’ viewpoint. After several interviews and assessments, these authors identified 9 essential requirements: accessibility, certifiability, portability, privacy, safety, security, stability, trustability, and usability.

Our systematic review has a number of limitations. Firstly, the articles it includes were of poor methodological quality; our recommendations should therefore be interpreted with caution. Additionally, validation studies have not been run on all of the included apps. Future studies should address this gap. Secondly, although these apps may be used in certain diseases as a complementary treatment alongside neurorehabilitation, they are not always applicable: for example, patients with cognitive impairment may have difficulty understanding the instructions of the app, and residual motor deficits in some patients may limit their ability to interact with the app without the help of a family member or carer. Therefore, each patient should be evaluated individually before an app can be recommended. We need further studies of good methodological quality and with sufficient sample sizes to explore these limitations and analyse other apps specifically designed for neurorehabilitation.

ConclusionsThe evidence suggests that for some neurological diseases, certain apps are effective and reliable when used as complementary treatment alongside rehabilitation, especially those apps designed to promote a healthy lifestyle, retrain balance, assess disorders, and let patients and their therapists communicate in real time. However, our results should be interpreted with caution due to the poor methodological quality of the included studies.

In view of the vast quantity of apps that may be useful for neurorehabilitation, app developers should be aware of the needs of patients with neurological diseases in order to create more valid and effective options. Likewise, app selection criteria should be available to make it easier for healthcare professionals, patients, and their families and caregivers to select the most suitable app for each case.

Correct implementation of apps in neurorehabilitation will require guaranteed access to mobile technologies by healthcare professionals, patients, relatives, and caregivers, and making the app industry aware of such aspects as usability, accessibility, and equal opportunities.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez Rodríguez MT, Collado Vázquez S, Martín Casas P, Cano de la Cuerda R. Apps en neurorrehabilitación. Una revisión sistemática de aplicaciones móviles. Neurología. 2018;33:313–326.