One of the factors contributing to transformation of migraine are sleep disorders, which can act as a trigger and/or perpetuating factor in these patients. This study’s primary objective was to identify predictive factors related to sleep quality in patients with chronic migraine (CM); the secondary objective was to identify any differences in psychological variables and disability between patients with CM with better or poorer sleep quality.

MethodsA total of 50 patients with CM were included in an observational, cross-sectional study. We recorded data on demographic, psychological, and disability variables using self-administered questionnaires.

ResultsA direct, moderate-to-strong correlation was observed between the different disability and psychological variables analysed (P < .05). Regression analysis identified depressive symptoms, headache-related disability, and pain catastrophising as predictors of sleep quality; together, these factors explain 33% of the variance. Statistically significant differences were found between patients with better and poorer sleep quality for depressive symptoms (P = .016) and pain catastrophising (P = .036).

ConclusionsThe predictive factors for sleep quality in patients with CM were depressive symptoms, headache-related disability, and pain catastrophising. Patients with poorer sleep quality had higher levels of pain catastrophising and depressive symptoms.

Uno de los factores contribuyentes en la cronificación de la migraña son los trastornos del sueño que pueden actuar como un factor precipitante y/o perpetuador en estos sujetos. El objetivo primario de este estudio fue identificar los factores predictores relacionados con la calidad del sueño en pacientes con migraña crónica (MC) y el objetivo secundario fue identificar si existían diferencias en variables psicológicas y de discapacidad entre los pacientes con MC que presentaban menor o mayor calidad del sueño.

MétodosSe llevó a cabo un estudio observacional, transversal, formado por 50 participantes con MC. Se registraron una serie de variables demográficas, psicológicas y de discapacidad mediante cuestionarios de autorregistro.

ResultadosSe observaron correlaciones directas, moderadas-fuertes, entre las diferentes variables de discapacidad y psicológicas analizadas (p < 0.05). En la regresión, se estableció como variable criterio la calidad del sueño y las variables predictores fueron los síntomas depresivos, la discapacidad relacionada con la cefalea y el catastrofismo ante el dolor que, en conjunto, explican el 33% de la varianza. En cuanto a la comparación de los grupos de mayor y menor afectación del sueño, se encontraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en la variable de síntomas depresivos (p = 0.016) y catastrofismo ante el dolor (p = 0.036).

ConclusionesLos factores predictores de la calidad del sueño en pacientes con MC fueron los síntomas depresivos, la discapacidad relacionada con la cefalea y, en menor medida, el catastrofismo ante el dolor. Los sujetos con peor calidad de sueño presentaron mayores niveles de catastrofismo ante el dolor y síntomas depresivos.

Migraine affects approximately 12.6% of adults in Spain.1 According to the latest data on the impact of migraine in Europe, migraine has a negative impact on quality of life (mental status, physical status, health), decreases productivity, and incurs high costs both for healthcare systems and for patients themselves. This is especially true for patients with chronic migraine, the most disabling form of the condition.2 Migraine constitutes a major public health problem,3 affecting over 10% of adults worldwide; prevalence is 2–3 times greater among women.4 In 2016, the Global Burden of Disease Study presented migraine as the first cause of years lived with disability worldwide in men and women aged 15–49 years.5

Each year, 2.5% of individuals with episodic migraine progress to chronic migraine.6 Migraine transformation occurs gradually, with the frequency of migraine attacks increasing progressively to the point that the patient experiences more headache days than headache-free days. Several factors have been found to promote migraine transformation; these include sleep disorders,7 which are highly prevalent among patients with migraine,8 and increase disability and decrease health-related quality of life.9 High frequency of migraine attacks is directly correlated with poorer sleep quality.10

Sleep disorders are more frequent among patients with chronic migraine than in those with episodic migraine.11 The association between chronic migraine and sleep disorders is complex; insomnia is the most prevalent sleep disorder in patients with chronic migraine.8 Insomnia is defined as difficulty falling asleep (> 30 min) at least 3 days per week and for over 3 months.12 Around 68%-84% of patients with chronic migraine present symptoms of insomnia nearly on a daily basis.11 Insomnia can increase the risk of headache, including migraine, by 40%.13

However, few studies have analysed sleep disorders in patients with chronic migraine and their association with psychological and disability-related variables, and the available data are from studies with considerable methodological differences. This study is intended to contribute further evidence on the subject. Our primary objective was to identify predictive factors associated with poor sleep quality in patients with chronic migraine. As a secondary objective, we aimed to detect differences in psychological and disability-related variables between patients with better and poorer sleep quality.

Material and methodsStudy designWe conducted a cross-sectional, observational study of a group of patients with chronic migraine. All participants received detailed information about the study and signed informed consent forms. Our study complies with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the research ethics committees of the region of Aragon and Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet (Zaragoza) (project no. CP03/2015). It also meets the STROBE guidelines for observational studies.14

Patient recruitmentPatients were recruited from the outpatient neurology consultation at Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet by non-probability sampling (consecutive sampling). They all met the following inclusion criteria: (1) diagnosis of chronic migraine according to the International Headache Society’s International Classification of Headache Disorders,15 established by a neurologist specialising in headache, and (2) age between 18 and 65 years.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: presenting a migraine attack at the time of assessment; other type of headache disorder; chronic and/or neurological diseases; cognitive, emotional, and/or psychological disorders such as depression, mood, and/or anxiety disorders diagnosed by a healthcare professional; and history of trauma or surgery to the upper half of the body.

We evaluated 65 patients, 15 of whom were excluded: 8 did not meet the inclusion criteria and 7 declined to participate.

ProcedureWe gathered the following demographic data: age, weight and height (body mass index), progression time of chronic migraine, employment status, and education level. We also gathered psychological and disability data using specific validated questionnaires, administered by a rater specialising in headache and craniofacial disorders.

To meet the secondary objective, we created 2 groups according to the impact of chronic migraine on sleep quality, using a cut-off score of 11 points on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI): patients scoring < 11 points were considered to have good sleep quality and those scoring ≥ 11 points were considered to have poor sleep quality.

Variables- -

The Spanish-language version of the PSQI was used to evaluate sleep quality in our participants.16 The questionnaire includes 19 items, grouped into 7 components, each of which is scored 0-3. In all cases, a score of 0 indicates no difficulty whereas a score of 3 indicates significant difficulty. The questionnaire explores the following areas: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction. The sum of scores for these 7 components yields a global score ranging from 0 to 21 points, with higher scores indicating poorer subjective sleep quality.16 The PSQI has demonstrated good psychometric properties, with an internal consistency of 0.81.16

- -

We also used the Spanish-language version of the 6-item Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) to evaluate headache-related disability (severity and impact on the patient’s life). The questionnaire has shown acceptable psychometric properties17 and has been validated for patients with chronic migraine.18 Total scores range from 36 to 78 points, and are classified into 4 categories depending on the severity of headache impact: little or no impact (36-49), some impact (50-55), substantial impact (56-59), and severe impact (60-78). The minimum clinically relevant change in HIT-6 scores for patients with daily chronic migraine is calculated at 2.3-2.7 points.19,20

- -

The Spanish-language version of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS)21 was used to evaluate the magnitude of catastrophic thinking about pain. The scale includes 13 items and assesses 3 dimensions: rumination, magnification, and helplessness. Each item is scored from 0 (never) to 4 (always), and total score ranges from 0 to 52, with higher scores indicating a higher level of pain catastrophising. The PCS has acceptable psychometric properties and an internal consistency of 0.79.21 The minimum detectable change is 10.45 points,22 and the cut-off score for early detection of patients with a tendency to catastrophise is 11 points.23

- -

The Spanish-language version of the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia24 was used to evaluate pain and fear of movement. The scale includes 11 items, scored on a 4-point Likert-type scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 4 (completely agree). Total score ranges from 11 to 44 points, with higher scores indicating greater fear of movement and pain. The scale includes 2 subscales (activity avoidance and somatic focus) and has demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties.24

- -

The Spanish-language version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)25 was used to detect symptoms of depression and anxiety in our sample. This scale includes 14 items, scored on a Likert-type scale from 0 to 4. Depression and anxiety are evaluated independently; higher scores indicate more severe depression and anxiety. The HADS has an internal consistency of 0.90 overall, or 0.84 and 0.85 for the depression and anxiety subscales, respectively.25 The minimal important difference has been established at approximately 1.5 points.26 The cut-off score ranges from 8 to 11 points for each subscale.27

We calculated the necessary sample size to evaluate the strength of association between the criterion variable (sleep quality) and the predictor variables. We calculated a statistical power of 80% (1–β) with a significance level of 0.05; we used ANOVA and a medium effect size (0.29). The analysis included 5 predictor variables. This calculation determined a sample size of 51 participants. Sample size was calculated using G*Power® 3.1.7 for Windows (Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Germany).28

Calculations were also based on a general guideline for regression analysis, according to which 5–10 participants are needed for each predictor variable used in the analysis.29 Considering that our study included 5 predictor variables, the sample should ideally include 50 participants.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was completed using the SPSS software, version 21.0 (IBM Corp; Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was set at P < .05 for all tests. Data are presented as means, standard deviation (SD), and range. Categorical variables are expressed as relative frequencies. We determined whether data followed a normal distribution with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (P > .05).

Multiple linear regression analysis was used to estimate the strength of association between poor sleep quality (criterion variable) and headache-related disability, symptoms of anxiety, symptoms of depression, pain catastrophising, and fear of movement (predictor variables). The variance inflation factor was calculated to determine whether either of the models presented multicollinearity.

The strength of association was examined using regression coefficients (β), P values, and adjusted R2. We report the standardised β coefficients for each predictor variable included in the final models to enable direct comparison between predictor variables in the regression model and the criterion variable.

We used the Pearson correlation coefficient to determine possible associations between variables. Correlation coefficients > 0.60 indicate a strong correlation, 0.30-0.60 a moderate correlation, and < 0.30 a weak correlation.30

The t test was used to compare outcome variables between patients with good vs poor sleep quality. We also calculated the effect size (Cohen d) for the results of this comparison using the Cohen method (small, d = 0.20-0.49; medium, d = 0.50−0.79; large, d ≥ 0.80).31

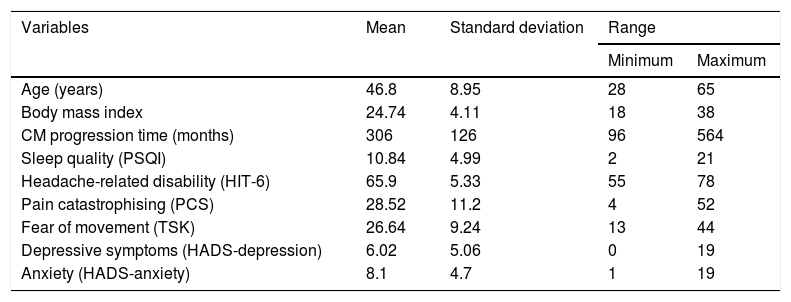

ResultsA total of 50 patients with chronic migraine met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate in our study. Women accounted for 92.6% of the sample. Most patients had completed secondary studies (54%), 24% had university studies, and 22% had primary studies. Regarding employment status, 40% of patients were unemployed, 10% were on medical leave, 3% were retired, and the remaining participants were active workers. Descriptive statistics of sociodemographic and self-reported clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Data followed a normal distribution (P > .05).

Descriptive statistical analysis of demographic and self-reported clinical characteristics.

| Variables | Mean | Standard deviation | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Maximum | |||

| Age (years) | 46.8 | 8.95 | 28 | 65 |

| Body mass index | 24.74 | 4.11 | 18 | 38 |

| CM progression time (months) | 306 | 126 | 96 | 564 |

| Sleep quality (PSQI) | 10.84 | 4.99 | 2 | 21 |

| Headache-related disability (HIT-6) | 65.9 | 5.33 | 55 | 78 |

| Pain catastrophising (PCS) | 28.52 | 11.2 | 4 | 52 |

| Fear of movement (TSK) | 26.64 | 9.24 | 13 | 44 |

| Depressive symptoms (HADS-depression) | 6.02 | 5.06 | 0 | 19 |

| Anxiety (HADS-anxiety) | 8.1 | 4.7 | 1 | 19 |

CM: chronic migraine; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HIT-6: Headache Impact Test; PCS: Pain Catastrophizing Scale; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; TSK: Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia.

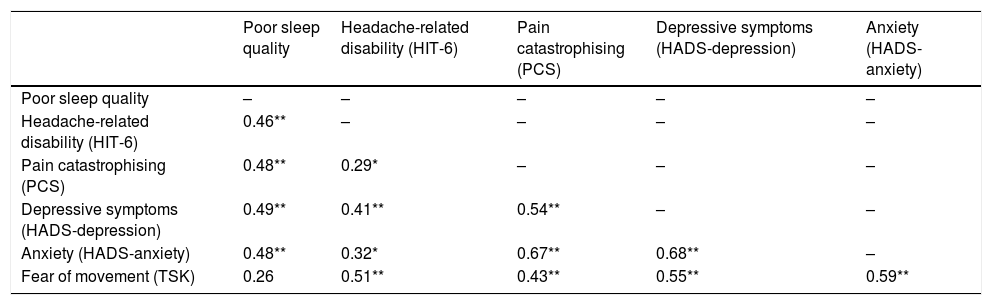

Table 2 shows the results from the correlation analysis examining bivariate associations between outcome measures. The strongest positive correlations were observed between anxiety and pain catastrophising (r = 0.67; P < .001) and between anxiety and depressive symptoms (r = 0.68; P < .001).

Pearson correlation coefficients.

| Poor sleep quality | Headache-related disability (HIT-6) | Pain catastrophising (PCS) | Depressive symptoms (HADS-depression) | Anxiety (HADS-anxiety) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor sleep quality | – | – | – | – | – |

| Headache-related disability (HIT-6) | 0.46** | – | – | – | – |

| Pain catastrophising (PCS) | 0.48** | 0.29* | – | – | – |

| Depressive symptoms (HADS-depression) | 0.49** | 0.41** | 0.54** | – | – |

| Anxiety (HADS-anxiety) | 0.48** | 0.32* | 0.67** | 0.68** | – |

| Fear of movement (TSK) | 0.26 | 0.51** | 0.43** | 0.55** | 0.59** |

HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HIT-6: Headache Impact Test; PCS: Pain Catastrophizing Scale; TSK: Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia.

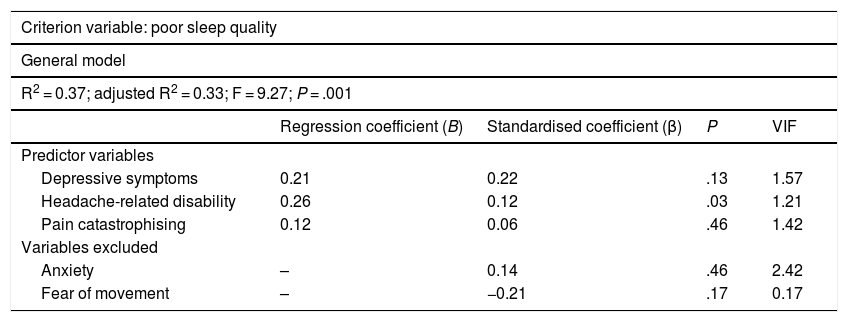

Table 3 presents the linear regression model for the criterion variable. Presence of depressive symptoms, headache-related disability, and pain catastrophising were found to be predictors of poor sleep quality, explaining 33% of variance. Anxiety and fear of movement were excluded from the analysis.

Linear regression analysis.

| Criterion variable: poor sleep quality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General model | ||||

| R2 = 0.37; adjusted R2 = 0.33; F = 9.27; P = .001 | ||||

| Regression coefficient (B) | Standardised coefficient (β) | P | VIF | |

| Predictor variables | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | 0.21 | 0.22 | .13 | 1.57 |

| Headache-related disability | 0.26 | 0.12 | .03 | 1.21 |

| Pain catastrophising | 0.12 | 0.06 | .46 | 1.42 |

| Variables excluded | ||||

| Anxiety | – | 0.14 | .46 | 2.42 |

| Fear of movement | – | −0.21 | .17 | 0.17 |

VIF: variance inflation factor.

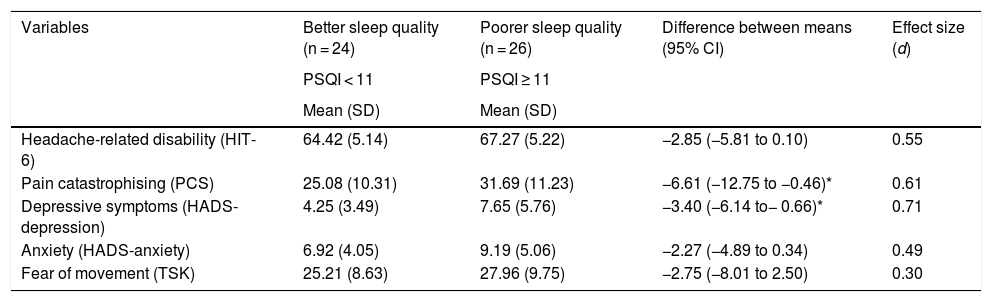

The comparative analysis of outcome variables between patients with better and poorer sleep quality only identified statistically significant differences in depressive symptoms (t = −2.5; P = .016) and pain catastrophising (t = −2.16; P = .036), which were more frequent among patients with poorer sleep quality (Table 4).

Comparative analysis of disability-related and psychological variables between patients with better and poorer sleep quality.

| Variables | Better sleep quality (n = 24) | Poorer sleep quality (n = 26) | Difference between means (95% CI) | Effect size (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSQI < 11 | PSQI ≥ 11 | |||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Headache-related disability (HIT-6) | 64.42 (5.14) | 67.27 (5.22) | −2.85 (−5.81 to 0.10) | 0.55 |

| Pain catastrophising (PCS) | 25.08 (10.31) | 31.69 (11.23) | −6.61 (−12.75 to −0.46)* | 0.61 |

| Depressive symptoms (HADS-depression) | 4.25 (3.49) | 7.65 (5.76) | −3.40 (−6.14 to− 0.66)* | 0.71 |

| Anxiety (HADS-anxiety) | 6.92 (4.05) | 9.19 (5.06) | −2.27 (−4.89 to 0.34) | 0.49 |

| Fear of movement (TSK) | 25.21 (8.63) | 27.96 (9.75) | −2.75 (−8.01 to 2.50) | 0.30 |

CI: confidence interval; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; SD: standard deviation; TSK: Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia.

This study was designed to determine the predictors of poor sleep quality in patients with chronic migraine and to identify differences in psychological and disability-related variables between patients with chronic migraine with better and poorer sleep quality. We also aimed to contribute additional data to the available evidence on sleep quality in patients with chronic migraine.

According to our results, poor sleep quality in patients with chronic migraine may be predicted by the following psychological and disability variables (in decreasing order of importance): headache-related disability, depressive symptoms, and pain catastrophising. These variables explain 33% of variance. Furthermore, patients with chronic migraine and poorer sleep quality (PSQI > 11) more frequently displayed depressive symptoms and pain catastrophising.

Our study found that headache-related disability may predict poor sleep quality in patients with chronic migraine. Migraine is associated with increased excitability of nociceptive pathways; in these patients, inputs from normal stimuli trigger abnormal responses, leading to an alteration in stimulus-response function.32 This phenomenon is known as central sensitisation.33 A number of psychological, emotional, and physical factors are known to increase CNS excitability, increasing pain sensitivity and therefore headache severity.34 According to Houle et al.,34 poor sleep is associated with more severe pain in patients with chronic migraine. Certain brain structures, including the thalamus, hypothalamus, and brainstem nuclei are common to both sleep and headache; this seems to be the basis of the association between poor sleep quality and headache.35,36 Poor sleep quality may increase pain sensitivity by increasing headache frequency; the frequency and severity of sleep disorders have been found to increase in parallel with headache frequency.34

Depressive symptoms have also been found to predict poor sleep quality in patients with chronic migraine, as they are more frequent in patients with chronic migraine and sleep problems than in those with better sleep quality. Epidemiological studies have shown that patients with migraine are 2 to 5 times more likely to present symptoms of depression and anxiety than individuals without this headache disorder.37,38 Anxiety and depression intensify the negative impact of migraine, increasing disability, decreasing health-related quality of life,39,40 and promoting headache transformation.8

Sleep disorders are more common in children and adolescents with severe anxiety and depression than in those without these disorders.41 The association between sleep and anxiety/depression seems to be bidirectional. On the one hand, sleep disorders are common in individuals with anxiety and/or depression. On the other hand, sleep problems cause emotional distress, which may promote anxiety and depression;41 insomnia is a common feature of mood disorders.42 Adults with severe depression present poorer sleep quality if they also have migraine.43

Sleep is an essential physiological process for the CNS, accounting for up to one-third of the human lifetime. In fact, it may be considered one of the most important psychophysiological processes for brain function and mental health.44 In line with our findings, George et al.45 demonstrated that chronic pain (including chronic headache) is associated with poorer sleep quality and depression. According to another study, poor sleep quality is associated with more severe depression;46 this is consistent with our results. This association may be due to the ability of sleep disorders and depression to trigger hyperalgesic responses in the CNS by increasing nociceptor excitability, which in turn favours central sensitisation.33 Headache, depression, and sleep disorders have common central mechanisms.47 Psychological disorders may worsen or trigger insomnia by causing hypervigilance and such other cognitive and behavioural processes as selective attention to threats and negative appraisal,48 which may also explain the variability in sleep quality among patients with chronic pain.49

Another variable that has been found to predict poor sleep quality in patients with chronic migraine is pain catastrophising; this phenomenon is also more marked in patients with chronic migraine and poorer sleep quality. Cognitive, affective, and behavioural responses are important factors in understanding the experience of pain. Pain catastrophising, which is considered a passive, maladaptive pain-coping strategy, is a negative cognitive and affective process that involves an increase in pain symptoms, helplessness, rumination, and pessimism; this predictor should be considered in pain conditions.50,51 The association between catastrophic thinking and poor sleep quality was first studied in 2003; in their study, Harvey and Greenall52 observed that individuals with insomnia more frequently presented catastrophic worry than individuals with good sleep quality. This pattern has been observed both in children53 and in adults.54

In 2017, Costa et al.55 observed that individuals with masticatory myofascial pain and headache presented poorer sleep quality and higher levels of pain catastrophising than those without headache. Another study demonstrated that individuals with chronic migraine present higher levels of pain catastrophising than patients with chronic temporomandibular disorders.56 Catastrophising has been shown to be a predictor of functional disability and poor quality of life in patients with migraine.57 Pain catastrophising may be considered both a risk factor for and a consequence of chronic pain, and has been associated with a higher incidence of headache in the general population.58

According to a recent neuroimaging study, patients with migraine and pain catastrophising display cortical grey matter changes in areas involved in the processing of sensory, affective, and cognitive aspects of pain. This may result from long-term repeated nociceptive stimulation, which would lead to increased sensitivity, mood disturbances, and maladaptive pain-coping strategies.59

The association between sleep disorders and migraine seems to be bidirectional.60 Insomnia may precipitate and/or promote pain in individuals with migraine.60 This association may be due to central sensitisation, which involves increased neuronal response to stimulation in the CNS. In this context, the CNS may change, distort, or magnify pain, causing alterations in pain intensity, duration, and location, altering the relationship between nociceptive stimulus and response.32 From a clinical viewpoint, central sensitisation may cause allodynia (a decrease in the pain threshold causing non-painful stimuli to become painful), or hyperalgesia (increased CNS response, leading to an exaggerated, prolonged pain response to noxious stimuli).61

A single night of total sleep deprivation has been found to induce generalised hyperalgesia and increase the incidence of psychological disorders in asymptomatic individuals.62 Partial sleep deprivation impairs endogenous pain-inhibitory function and increases pain in asymptomatic individuals.63 These findings suggest that sleep alterations may promote CNS hyperexcitability in patients with chronic pain, and even act as a trigger factor in these individuals. Insomnia can increase the risk of headache, including migraine, by 40%.13

According to our results, sleep quality should be evaluated in patients with chronic migraine; treatment should mainly be based on a biopsychosocial model, with equal emphasis placed on psychological and physiological aspects. Our results also underscore the multidimensional impact of chronic migraine on patients’ health-related quality of life.

LimitationsWomen accounted for 92.6% of the sample, which may limit the generalisability of our results. However, scientific evidence has consistently shown a higher prevalence of migraine in women. Our study did not gather data on the participant’s phase of the menstrual cycle or the medications taken at the time of assessment. Furthermore, we did not gather data on other sleep disorders. Our study followed a cross-sectional design; longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate whether the variables associated with poorer sleep quality change over time and whether this has an impact on sleep quality. Lastly, our study evaluated the different variables exclusively in patients with chronic migraine; it would be interesting to analyse these variables in individuals with episodic migraine and controls.

These limitations may help future studies to reach more precise and specific conclusions.

ConclusionDepressive symptoms, headache-related disability, and, to a lesser extent, pain catastrophising are predictors of poor sleep quality in patients with chronic migraine.

Individuals with poorer sleep quality present higher levels of pain catastrophising and depressive symptoms.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. This study has received no specific funding from any public, private, or non-profit organisation.

Please cite this article as: Garrigós-Pedrón M, Segura-Ortí E, Gracia-Naya M, La Touche R. Factores predictores de la calidad del sueño en pacientes con migraña crónica. Neurología 2022;37:101–109.