Q fever is a bacterial zoonosis caused by Coxiella burnetii, whose main reservoir is sheep and goats. The acute-phase infection is symptomatic in approximately half of cases.1 The most frequent manifestations include flu-like symptoms, which may be accompanied by pneumonia or granulomatous hepatitis. The condition may cause miscarriage or preterm birth in pregnant women.2 Involvement of the central nervous system is an infrequent complication (1%-22% of cases), manifesting with such syndromes as meningoencephalitis (0.2%-7%), optic neuritis, or acute neuropathies.3–6

We present a case of C. burnetii infection that is unusual due to its stroke-like onset and the co-presence of 2 neurological complications, meningoencephalitis and optic neuritis.

Our patient is a 42-year-old woman living at a livestock farm who 5 months previously had presented fever with interstitial pulmonary involvement and cholestasis of undetermined cause, for which she received empirical treatment with azithromycin. She was asymptomatic at discharge. She visited the emergency department due to a witnessed episode of sudden-onset language impairment, which led to code stroke activation when she arrived at the hospital.

In the initial examination, the patient showed no fever or meningeal signs. She presented global aphasia, right homonymous hemianopsia, and mild paresis of the right upper limb (13 points on the NIHSS).

A simple CT scan revealed no significant alterations. Due to the progression time of acute focal deficit of less than 3 hours, we administered intravenous thrombolysis, observing no immediate improvement. A CT angiography detected no vascular occlusion. In the following hours, we obtained more reliable information on the symptoms of the previous days, including headache, nausea, vomiting, and left monocular vision impairment. The patient also developed fever and was started on empirical antibiotic and antiviral treatment.

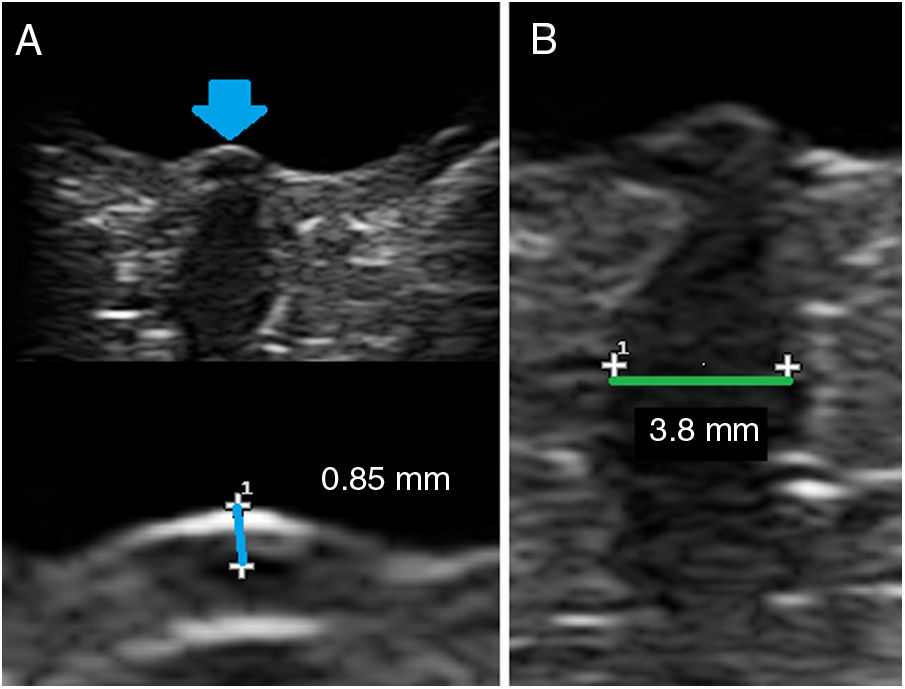

A lumbar puncture performed at 24 hours due to thrombosis revealed pleocytosis (290 mononuclear cells) and high protein levels (1.37 g/dL) without low glucose levels. An MRI study revealed leptomeningeal contrast uptake between the cerebellar folia (Fig. 1), with no meningeal uptake in other regions. A C. burnetii (Q-Fever) phase 2 serology test yielded positive results, with IgG titres of 1/160-640 and IgM titres of 1/100. Negative results were obtained in the remaining serological tests, cultures, and the multiplex polymerase chain reaction assay.

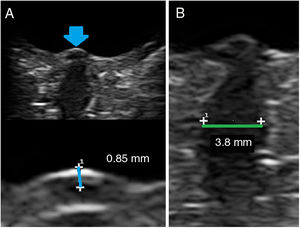

The neuro-ophthalmological evaluation revealed enlarged blind spot bilaterally, visual acuity of 0.4 in the left eye and 0.7 in the right eye, and bilateral haemorrhagic papilloedema. An orbital ultrasound study revealed increased diameter of the optic nerves with no signs of intracranial hypertension (no oedema under the dural sheath), suggesting bilateral optic neuritis (Fig. 2).

We started treatment with intravenous doxycycline and levofloxacin for 3 weeks and boluses of methylprednisolone, subsequently administered in decreasing oral doses. The patient progressively improved until symptom resolution, which persists after one year.

Therefore, we present a case of Q fever with several clinically relevant peculiarities: different nervous system disorders (meningoencephalitis and bilateral optic neuritis) and manifestation as a stroke mimic.

In general, neurological involvement due to C. burnetii infection is infrequent but varied,1,3–8 and includes:

- -

Meningitis or meningoencephalitis: among encephalitis symptoms, we may highlight rhombencephalitis and cerebellitis. Manifestations may be typical or unusual (akinetic-rigid syndrome, cognitive impairment, pseudotumor cerebri).

- -

Septic embolism

- -

Myelitis

- -

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis

- -

Cranial neuritis

- -

Peripheral neuropathy: mononeuritis multiplex, symptoms on the spectrum of Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Cases with multiple simultaneous complications are exceptional in the literature.

Serological diagnosis is established by titres of anti-phase 2 IgG antibodies >1:200 or IgM antibodies >1:500 or titres multiplied by 4 in 2 consecutive samples. Our patient met these criteria, even though the antibody peak titre was probably reached several weeks before, when she presented systemic symptoms. In the context of central nervous system involvement, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis reveals nonspecific data of lymphocytic pleocytosis, with or without high protein levels and no glucose uptake. Definitive diagnosis is established by liquid culture for isolating the pathogen, although C. burnetii is difficult to culture. From a radiological viewpoint, CT and MRI studies show no alterations, although non-specific parenchymal lesions and brain oedema have been described.8

The treatment of choice is doxycycline, as well as fluoroquinolones due to their good CSF penetration.9 Corticosteroids have been used successfully in cases of neuritis or acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Outcomes are generally good, even if treatment is delayed, although fatal outcomes and significant neurological sequelae have occasionally been reported.1

In conclusion, Q fever must be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with multiple neurological syndromes in such endemic areas as Spain. Co-presence of such other systemic symptoms as pulmonary or hepatic involvement, together with fever, accompanied by exposure to animals may support suspicion of the infection. When this aetiology is not suspected, diagnosis is difficult as this is an infrequent complication with no specific clinical or paraclinical findings.

FundingThis study received no funding of any kind.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Romero-Sánchez CM, Ayo-Martín O, Tomás-Labat ME, Segura T. Meningoencefalitis por fiebre Q como stroke mimic. Neurología. 2021;36:477–478.