Up to 70% of children currently treated by Palliative Care Units in Europe are neurological patients. Our objective is to assess the knowledge, interest and involvement in paediatric palliative care (PPC) among Spanish paediatric neurologists.

Material and methodsWe contacted 297 neuropaediatricians by and attached a 10-question multiple choice test. This questionnaire was related to the level of knowledge of PPC, identification of patients requiring this specific care, involvement of a paediatric neurologist, use of local palliative resources, and formal training in this subject.

ResultsParticipation rate was 32% (96/297). Around 90% knew the definition of PPC, could identify patients with a short-term survival prognosis, and had treated children who eventually died due to their illnesses. A “non resuscitation order” had been written by 61% of them at least once; 77% considered the patient's home as the preferred location of death (if receiving appropriate care), 9% preferred the hospital, and 14% had no preference for any of these options. Just over half (52%) had contacted local PC resources, and 61% had referred or would refer patients to be seen periodically by both services (PC and Paediatric Neurology). More than half (55%) consider themselves not trained enough to deal with these children, and 80% would like to increase their knowledge about PPC.

ConclusionThe paediatric neurologists surveyed frequently deal with children who suffer from incurable diseases. Their level of involvement with these patients is high. However, there is an overwhelming necessity and desire to receive more training to support these children and their families.

Actualmente en torno al 70% de los niños atendidos en cuidados paliativos (CP) son enfermos neurológicos. Nuestro objetivo es valorar el grado de formación, interés e implicación de los neuropediatras de España en relación con los cuidados paliativos pediátricos (CPP).

Material y métodosNos dirigimos a 297 neuropediatras mediante correo electrónico, adjuntando 10 preguntas tipo test. En ellas se hace referencia al conocimiento de los CPP, reconocimiento de pacientes con estas necesidades, implicación del neuropediatra, conocimiento y utilización de recursos paliativos, y formación individual sobre estos temas.

ResultadosParticipa el 32% (96/297). En torno al 90% conoce qué son los CPP, reconoce a pacientes con pronóstico vital acortado y ha atendido a niños que finalmente han fallecido debido a su enfermedad. El 61% ha realizado alguna vez un informe de «no reanimación». El 77% considera la casa como el lugar idóneo para fallecer (si la atención es adecuada), el 9% el hospital y el 14% cualquiera de los dos previos. El 52% ha contactado alguna vez con recursos locales de CP y el 61% deriva o derivaría pacientes para que sean seguidos conjuntamente (por CP y neuropediatría). Más de la mitad considera no tener formación suficiente para atender estos pacientes y al 80% le gustaría ampliar sus conocimientos en CPP.

ConclusiónLos neuropediatras encuestados atienden con frecuencia niños con pronóstico vital acortado. El grado de implicación con estos pacientes es alto, aunque mayoritariamente se necesita y se desea mayor formación en CP para proporcionar mejor atención a estos enfermos.

Paediatric palliative care (PPC) aims to improve treatment and quality of life for paediatric patients who have terminal or potentially fatal diseases, and for their families, by providing continuous personalised care. It begins at diagnosis of the disease and continues regardless of whether or not the child is also receiving treatment specific to his or her illness. Understanding the palliative approach from the time of diagnosis enables us to establish personalised courses of treatment which improve quality of life for both the patient and the family.1,2

The unique nature and complexity of PPC are due to several factors2–4:

- -

Low prevalence. Compared to the adult population, the number of paediatric cases requiring palliative care is much lower. This fact, added to these patients’ wide geographical distribution, can pose problems in the areas of organisation, training, and care costs.

- -

The wide variety of conditions (neurological, neoplastic, metabolic, chromosomal, cardiac, respiratory, and infectious conditions; complications of pre-term birth; severe cranial and/or spinal trauma), and an unpredictable disease duration. Many diseases are rare, and some lack a precise diagnosis.

- -

Limited availability of medications approved for use in children. At times, there is no specific information regarding the use of certain drugs in children.

- -

Developmental aspects. Children develop continuously on the physical, emotional, and cognitive levels, which affects communication, education and support methods.

- -

The role of the family. In most cases, parents act as their children's representatives when it comes to clinical, therapeutic, ethical and social decisions, although this depends on the child's age and level of competence.

- -

Lack of training. There is a significant lack of training and awareness regarding the care of dying children among healthcare professionals specialising in children and adolescents.

- -

Emotional involvement. When a patient is dying, it may be very difficult for the family and caregivers to accept treatment failure, the incurable nature of the disease, and death. This is even more acute when the patient is a child.

- -

Pain and mourning. Following the death of a child, the feeling of loss is often prolonged and more complex.

- -

Social impact. During the course of a debilitating disease, the child and all the family members may find it hard to maintain their roles in society.

Currently, 70% of children attended in paediatric palliative care units (PPCUs) in Europe suffer from diseases other than cancer. Most are neurological diseases. Since so many of these children have neurological diseases, we decided to evaluate the levels of training, interest and involvement of paediatric neurologists in Spain with regard to PPC.5

Material and methodsCross-sectional descriptive study carried out by means of a questionnaire and distributed in March 2011. We contacted the members of the Spanish Society of Paediatric Neurology (SENEP) and other professionals dedicated to neuropaediatrics (mainly paediatrics residents specialising in paediatric neurology and paediatric neurologists in the Madrid/Central Area paediatric neurology group) by e-mail, attaching a brief questionnaire with 10 multiple choice questions. We provided information on how to fill it in, and also indicated the option of ticking multiple responses to a single question, if appropriate. Participants were asked to return the completed questionnaire to the address provided.

The questionnaire is shown in Table 1. Questions touch on the following topics: knowledge of PPC work (question 1); recognising neurology patients who may benefit from palliative care (questions 2 and 3); involvement of the paediatric neurologist in matters such as “do not resuscitate” and opinion on the best place to die (questions 4 and 5); knowledge of nearby resources for these patients, how they are used and any difficulties with them (questions 6, 7, and 8) and personal ability to provide care for these children and interest in additional training (questions 9 and 10).

Questionnaire sent to paediatric neurologists.

| 1. What do you understand by “paediatric palliative care”? |

| a. Care provided to children who are going to die of an incurable disease when they are expected to live less than 6 months |

| b. The total and continuous care intended to improve quality of life of children who are going to die of an incurable disease, beginning when it is diagnosed |

| c. Care given to children with incurable diseases when they are about to die or experiencing extreme suffering |

| 2. Can you identify any of your current paediatric neurology patients from outpatient clinics or hospital wards as having life-limiting diseases, that is, incurable diseases that result in premature death? |

| a. Yes, one or more |

| b. No, none of my current patients falls into this category |

| 3. If you answered “yes” to the previous question, have any of these patients died from an incurable disease or its complications? |

| a. Yes, one or more |

| b. No, none of them |

| 4. Have you ever issued a “do not resuscitate” order for one of your patients? |

| a. Yes, on one or more occasions |

| b. No, never |

| c. Only at the family's request to “not do any more” |

| 5. In your opinion, where is the best place for these patients to die? |

| a. At home, provided that they are able to receive proper care |

| b. At the hospital, so that families do not feel abandoned |

| c. In an intensive care unit so as to employ all possible measures until the end |

| 6. Do you know of any resource programmes in your autonomous community/health district/hospital that work with these children? |

| a. No |

| b. Yes, they do exist but I have never worked with them |

| c. Yes, they do exist and I have worked with them at some point |

| 7. If you could or wanted to refer a patient to a palliative care unit, when would you do so? |

| a. Upon diagnosis of an incurable and life-limiting disease, depending on the disease, the vital prognosis, and expected progression. |

| b. At the request of the parents |

| c. Upon discovering progressive and irreversible deterioration with increased complications and/or care requirements |

| d. When the patient was in a state of extreme suffering |

| e. Never |

| 8. Is it or would it be difficult for you to refer a patient for palliative care? |

| a. Yes, because I do not know of any local PC units |

| b. Yes, since families are frightened of the term “palliative care” |

| c. Yes, since I would prefer to have these patients treated by the neurology department until the end |

| d. No, I would refer the patient for monitoring by both departments |

| e. No, I would refer the patient for monitoring by palliative care if I could not do anything more. |

| 9. Do you feel that as a paediatric neurologist, you are properly trained and capable of caring for a patient with an incurable disease in the final stage? |

| a. Yes |

| b. No |

| c. I would prefer not to be involved in this stage of the disease. |

| 10. If you had the option of attending a course for paediatric neurologists on paediatric palliative care, would you do so? |

| a. Yes, I feel that it would help me manage my patients |

| b. Yes, but I would rather spend my time being trained in other areas |

| c. No, I am not interested |

Once we received the e-mail responses, we recorded data in an Excel 2003 spreadsheet for later analysis. Quantitative data were given as absolute frequencies (when necessary) and percentages.

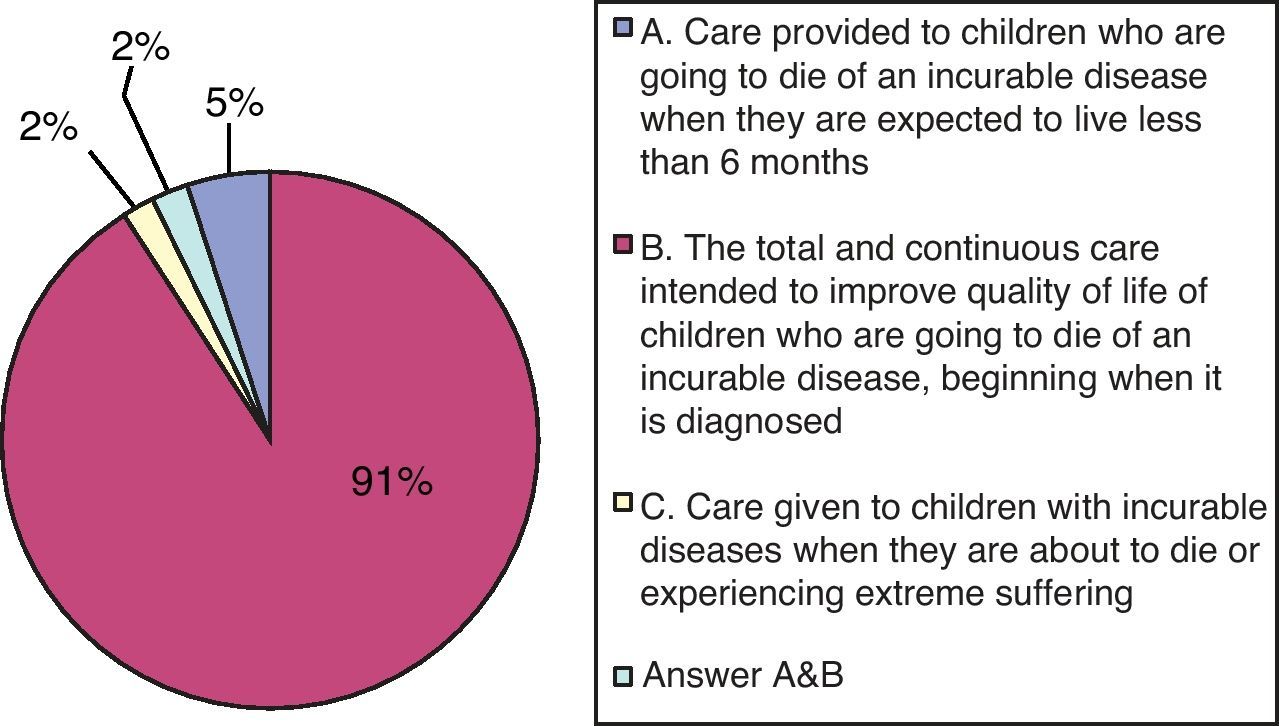

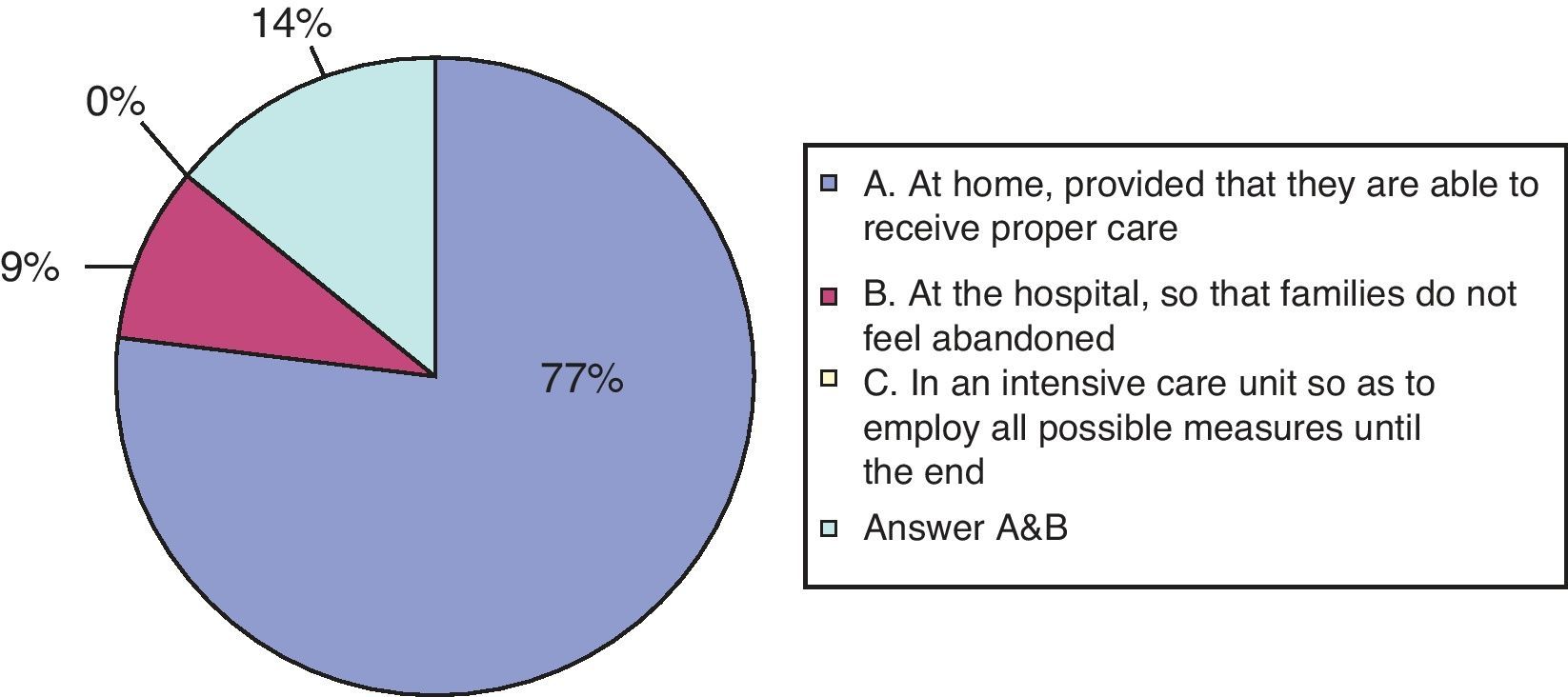

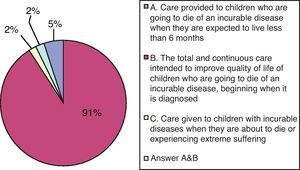

ResultsOf the 297 paediatric neurologists to whom we sent the questionnaire, 96 answered (32%). On the first question, regarding the definition of PPC, the vast majority (91%) knew it as multidisciplinary, continuous care provided to children who are dying of an incurable disease, beginning at time of diagnosis, and which focuses on improving their quality of life. Another 5% thought that it was restricted to the patient's last 6 months of life, and 2% thought that it was only provided in cases of extreme suffering (see Fig. 1).

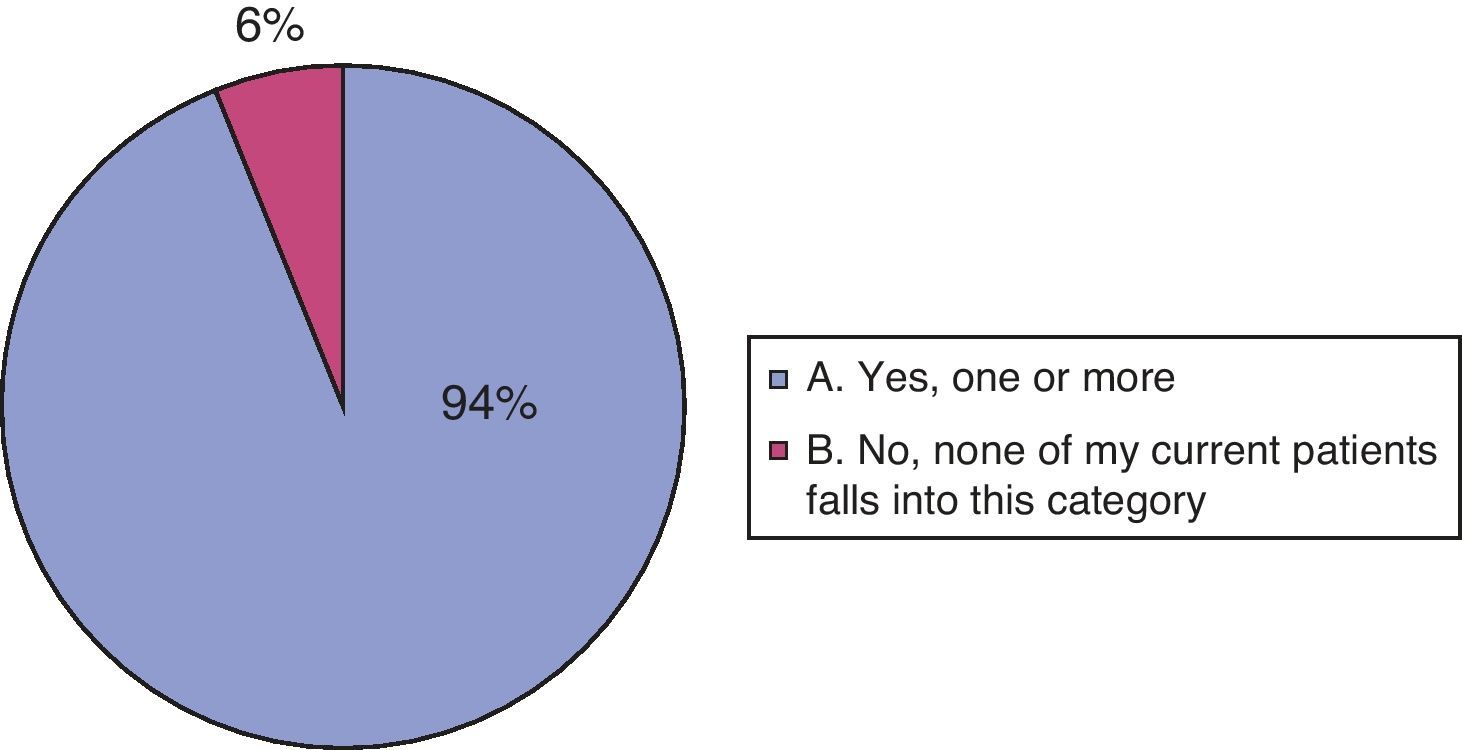

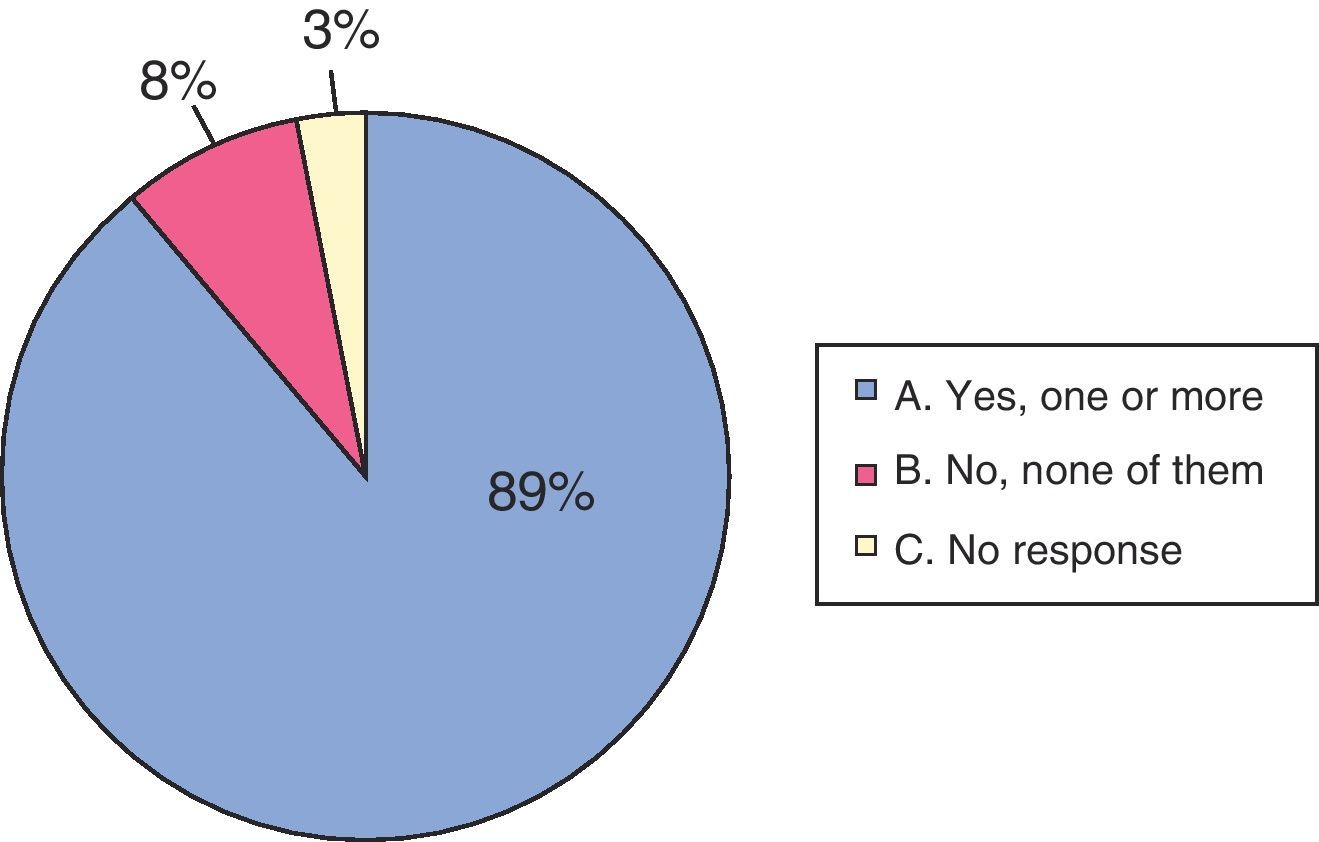

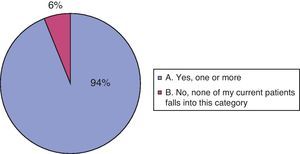

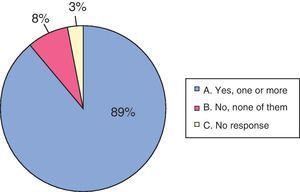

Ninety participants (94%) stated that one or more of their current patients had a disabling or life-limiting disease. The other 6 paediatric neurologists stated that they were not currently treating any patients meeting the above criteria. On the third question, asking whether a patient had died from a neurological disease or its complications, 85 doctors (89%) responded in the affirmative (see Figs. 2 and 3).

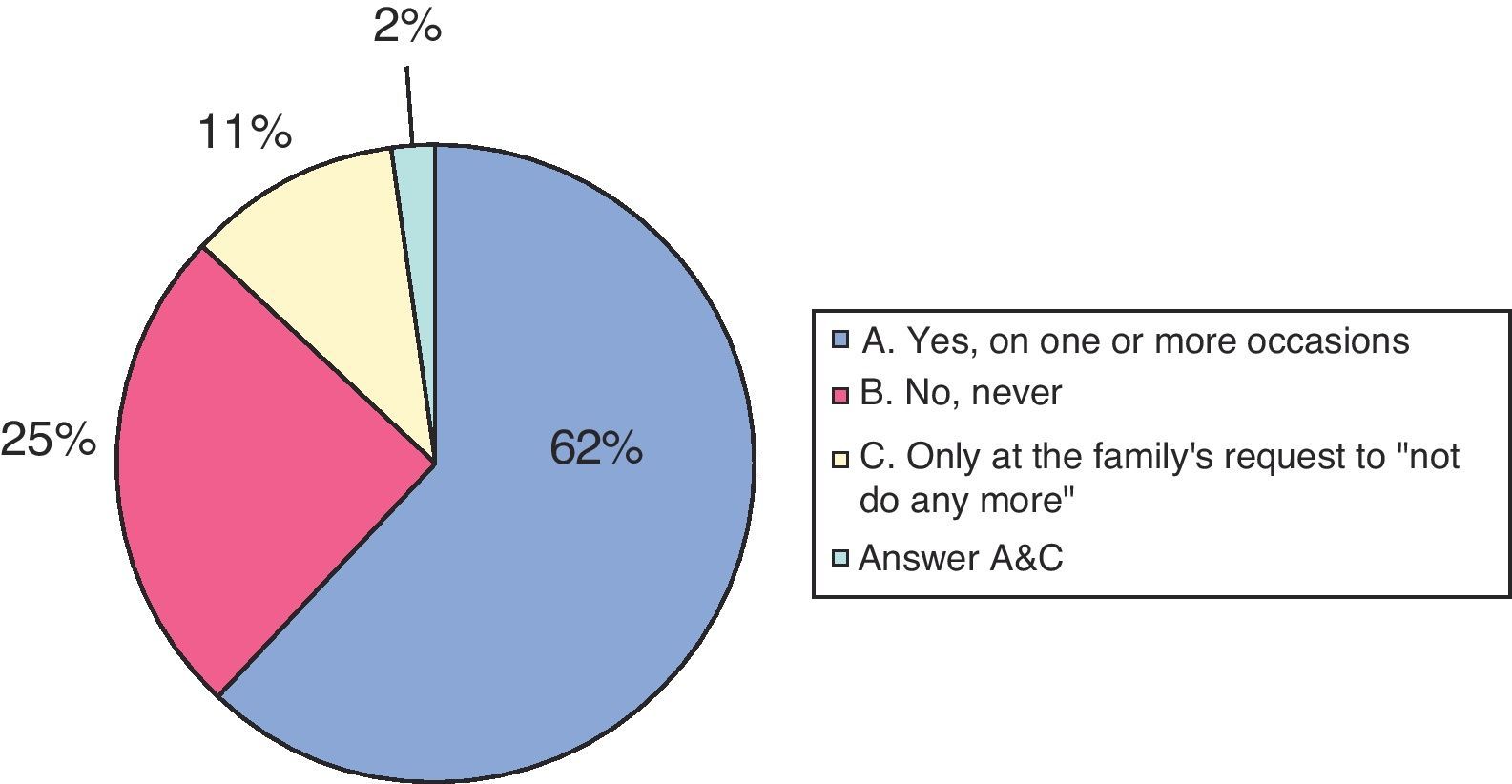

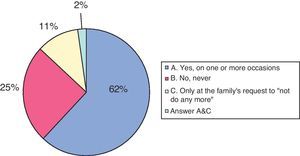

Regarding “do not resuscitate” orders, 62% had prepared them on one or more occasions, 25% had never prepared them, and 11% (11) had only prepared them following a family's request to “not do any more” (see Fig. 4).

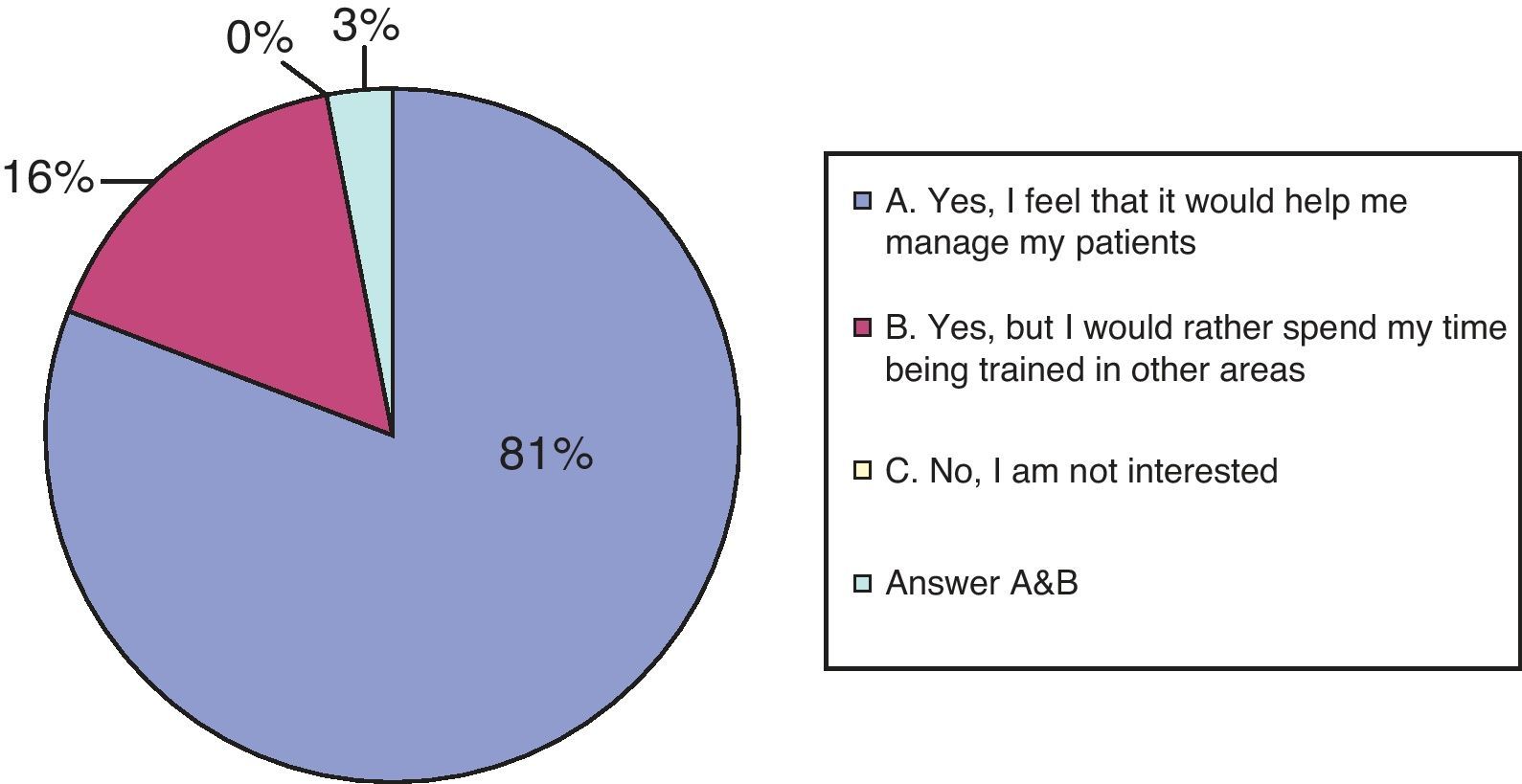

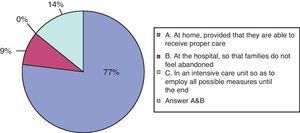

None of the participants believed that children needing PC should die in an intensive care unit. Provided that patients receive an appropriate level of care, 77% of the doctors felt that home was the best place for the patient to die. In contrast, 9 doctors stated that the hospital was preferable so that family members would not feel alone and abandoned. The remaining 14% felt that either of those options was a good choice (see Fig. 5).

Seventy percent identified resource programmes in their autonomous community, health district, or hospital that aid with children needing palliative care. However, 25% (17 of the respondents) had never requested their assistance, despite being aware of these resources. On the other hand, 30% did not know of any local resources aiding with children on palliative care.

In response to the question about wanting or being able to refer patients to a PCU, 44% of the participating doctors stated that they would do so if they detected progressive and irreversible deterioration with increased complications and care needs. Another 38% stated that they would do so upon diagnosing an incurable or life-limiting disease. Five doctors stated that they would recur to a PCU in either of the above situations. Three stated that they would do so only at the parents’ request. In answer to this question, 5 doctors considered the first 4 answers to be possible options, including the situation of “extreme suffering” indicated in option ‘D’. However, none of the participants selected the last option, “never”, meaning that all of them believe that the patient should be referred at some point.

When asked about the difficulties of referring a patient to a palliative care unit, more than half (about 65%) did not feel it was complicated. Fifty-eight doctors stated that they refer or would refer patients so that they could be attended by both units (paediatric neurology and paediatric palliative care); one respondent would refer the patient immediately due to being unable to do anything more. In contrast, 32 participants (33%) found referral difficult for the following reasons: 23 (24%) did not know of any nearby palliative care units for children; 8 stated that the term “palliative care” frightens families; and another doctor felt that the neurology department should be the only one providing care for these patients until the end.

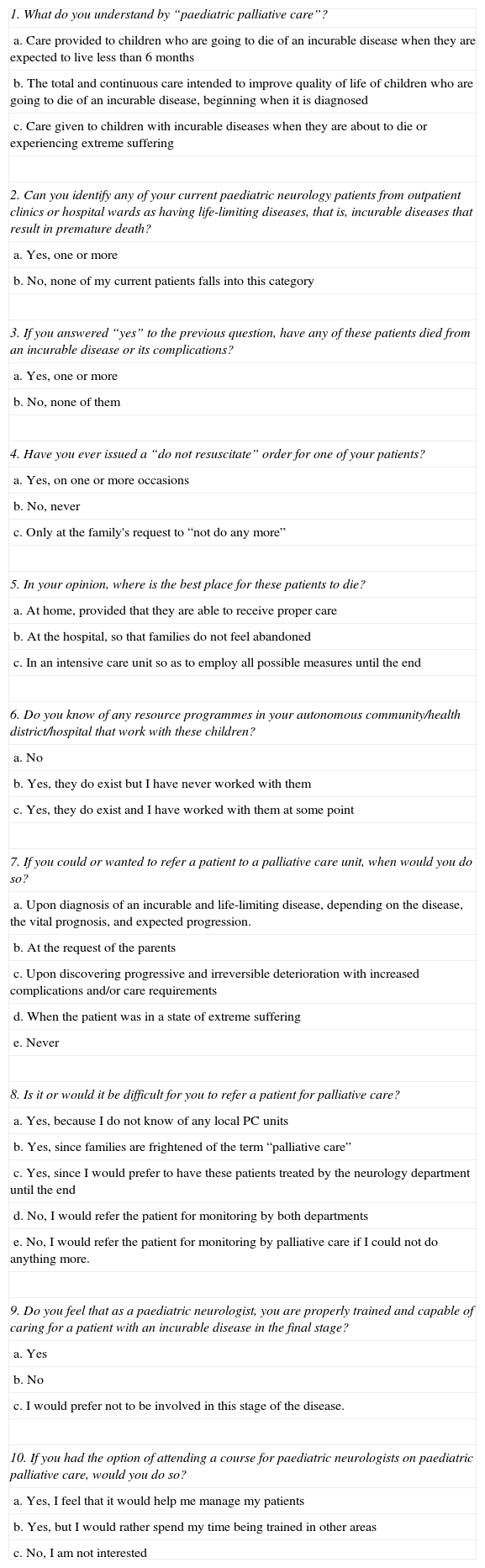

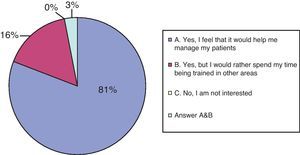

Regarding question 9, on training and ability to care for a patient with an incurable disease in the terminal stage, 40% felt that they were prepared and 55% did not. Another 3 explicitly stated that they would prefer not to be involved in this stage of the disease. Regarding the possibility of attending a course on PPC to receive further training in these areas, most (81%) were receptive and felt that such a course would be useful in order to offer their patients better care. In contrast, 16% would prefer to spend their time researching areas of paediatric neurology other than PPC (see Fig. 6).

DiscussionIn March 2006, a group of health professionals from Europe, Canada, Lebanon and the United States met in Trento (Italy) to discuss the current state of PCC in Europe.6 (International Meeting for Palliative Care in Children, Trento, IMPaCCT). They compared palliative care services in different countries, defined PPC, identified best practises, and reached a consensus on minimum standards. The meeting produced a consensus document for Europe that defined and identified standards of care for children with incapacitating or terminal diseases. They adopted the definition of PCC put forth by the WHO: active total care of the child's body, mind and spirit, including providing support to the family. IMPaCCT states that the main care objective is to increase the quality of life of the child and his/her family. It indicates that palliative care should be initiated as soon as the child is diagnosed with a disease entailing a life-limiting or life-threatening condition. A life-limiting condition is one in which premature death is common (spinal muscular atrophy type I). A life-threatening disease is one in which there is a high probability of premature death due to the severity of the illness itself, but in which long-term survival in adulthood is also likely (cancer).

Previously published studies7 define 4 groups of patients:

- -

Group 1: patients suffering from life-threatening conditions. Curative treatment does exist, but it may fail. Example: cancer patients.

- -

Group 2: patients suffering from conditions inevitably leading to premature death. However, given proper treatment, life can be prolonged and quality of life can be improved during long periods. Example: cystic fibrosis patients.

- -

Group 3: patients with progressive diseases for which only palliative and no curative treatments are available, and who may require care during many years. Example: severe metabolic disorders and neurodegenerative diseases.

- -

Group 4: patients suffering from irreversible but non-progressive conditions. These conditions result in complications which lead to premature death. Examples: Severe cerebral palsy in childhood and sequelae from major trauma or infections.

We should reiterate that only 32% of the surveyed paediatric neurologists responded. This low participation rate may have been due to several factors: (a) some of the doctors receiving a survey may not be exclusively dedicated to paediatric neurology, and only spend part of their working hours in the general paediatrics unit of a hospital or clinic; (b) some professionals may be principally dedicated to prevalent neurological diseases without significant effects on vital prognosis (headaches, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, learning disorder, etc.); (c) the general belief — also present among paediatric neurologists — that neurological patients suffer less than is really the case, a belief which downplays the benefits provided by good palliative care; and (d) the association of the word “palliative” with cancer, although the majority of patients in PPCUs suffer from neurological conditions. All of the above considerations may have had an impact on participation, and as a result, doctors dedicating the larger part of their time to severe or life-limiting neurological diseases may have shown a greater interest in filling out and returning the questionnaire. In turn, this may have influenced the results, as we observe from the most frequent responses to questions 2, 3, and 4 (see following paragraphs).

Most paediatric neurologists who responded are aware of PPC services. It is very important that we highlight that the WHO definition of palliative care, which was accepted by IMPaCCT, never states that palliative care should only be provided during the patient's last 6 months of life, or in end stages marked by “extreme suffering”. It states that care begins when the child is diagnosed with a life-limiting or life-threatening disease.6

In the same way, most participants stated that one or more of their patients had a life-limiting disease. Additionally, a large percentage had treated children who eventually died from a neurological disease or one of its complications. These data make sense when we consider that most patients in PPCUs have neurological conditions (about 70%), and many of them die. Despite being aware of PPC services and working with patients whose life expectancy is curtailed, a significant number of paediatric neurologists have never drawn up a “do not resuscitate” order (25%). It is possible that this percentage is the result of the array of differences in professional experience among the paediatric neurologists. Some have been practising for many years, while others have just begun. However, it may also be a sign of reduced professional involvement, since many of these patients will experience complications of their underlying condition involving an imminent possibility of death. (Examples of such cases are respiratory infections in hypotonic children or those with cerebral palsy.) This brief reflection, alongside the fact that 55% of those surveyed do not feel sufficiently trained or able to manage the end-of-life stage of such a disease, points to the urgent necessity for increased training for all professionals involved. In fact, with regard to the question about attending a course on PPC, most professionals stated that it would be useful. It seems clear that improved training in palliative care would bring about a change in professional attitudes regarding care and follow-up for paediatric neurology patients and their families.

As stated in the standards drawn up at the international meeting mentioned above, a number of studies have been carried out in recent years that provide important information on children's mortality, place of death, and the specific needs of children and their families. They conclude that children generally prefer to be at home, and that families prefer to care for them at home during their illness until death.4,8 Of the survey participants, 77% agreed that the home was the best place for children to die. The hospital (indicated by 9% of the professionals) cannot be considered incorrect; if no home care support services are available nearby, or if the family has come to a standstill, aiding both the patient and the family is crucial. In any case, none of the respondents indicated intensive care units as the best places for children to die.

The questionnaires were sent out by e-mail and answers were received in the same format. Respondents were not required to list their exact location or hospital type (primary, secondary or tertiary care centres). Some included this information voluntarily, but many others did not. Due to the dispersion of respondents and lack of information about their workplaces, an analysis of practitioners’ knowledge of resources open to children receiving palliative care in the same autonomous community, health district or hospital cannot determine if such programmes do not exist, or if they do exist but have been overlooked. There are 3 PPCUs in Spain. The first was founded in 1991 at Hospital Sant Joan de Déu in Barcelona. The second, founded in 1997, is at Hospital Universitario Materno Infantil, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Canary Islands. The most recent is located at Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús, Madrid, founded in 2008. The latter currently provides care to children residing anywhere in Madrid Province. This multidisciplinary team is dedicated exclusively to PPC and provides care 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Increasing attention is being focused on this team's work in conferences, congresses and seminars. However, it still needs more publicity: a survey published in 2010 concluded that this unit was still unknown to a large number of health professionals in Madrid, despite dedicated efforts by the unit since it was founded.9

In other parts of the country, we find palliative care units that do offer care to paediatric patients, depending on practitioners’ individual and collective experience and the child's age and underlying disease. What is interesting here is the percentage of respondents who are aware that these services exist, but have never worked with them (17%). Also interesting are their explanations as to why contacting a PPCU is difficult: some refrain from this step because the term “palliative care” frightens the patients’ families, and one respondent believes that these patients should be monitored by the neurology department until the end, with no need for PPC. We should also highlight a statement by IMPaCCT: the aim of paediatric palliative care is to provide the best total care. It makes no mention of “maintaining sole and exclusive control over the patient”. An ideal situation would be one of joint support provided by different sub-specialties.10,11

The best time to contact a PCU is when the practitioner detects progressive and irreversible deterioration accompanied by an increased number of complications. This is the ideal response, provided by 44% of the participants. However, the answer ‘A’ (“upon diagnosis of an incurable and life-limiting disease, depending on the disease, the vital prognosis and expected progression”) should also be considered valid. This means that palliative care for an incurable disease should be provided upon its diagnosis, without discontinuing any necessary curative treatments. This approach must be put forth by the care group of reference, referring in this case to the paediatric neurologist and the primary care paediatrician. The moment to contact a specialised palliative care team will depend on the clinical, social, and psychological complexity of the patient's (and family's) case. Experience tells us that early referral results in more complete and satisfactory care. Ideally, an interdisciplinary team would care for all of the patient's needs from diagnosis throughout all stages of his or her disease. In any case, if the patient is experiencing extreme suffering, care should be provided by a team which has already built a trusting relationship with the family.12

ConclusionsWhile mindful of the limitations of our sample, we can state that most of the participating paediatric neurologists know what PPC is and how it works, can identify which of their patients suffer from life-limiting illnesses, and have treated children who eventually died due to a neurological disease or a complication of such a disease. In general, the degree of involvement with these patients is high, although additional training in PC is needed overall so as to provide these patients with more complete care. Most respondents expressed a wish to receive specific training in these areas in order to better care for their patients. Public health systems should take significant steps towards improving training in the area of palliative care, especially when we consider how many paediatric neurologists are interested in learning about end-of-life care for patients and their families.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Calleja Gero ML, et al. Cuestionario sobre cuidados paliativos a neuropediatras. Neurología. 2012;27:277–83.

This study was featured as an oral presentation at the 35th Annual Meeting of the Spanish Society of Paediatric Neurology (June 2011, Granada). Submission date: 05 August 2011.