We aimed to analyse the prevalence, characteristics, and management of simple and complex febrile seizures. The secondary objective was to compare the risk of underlying organic lesion and epilepsy in both types of seizures, with a particular focus on the different subtypes defining a complex febrile seizure.

Material and methodsWe performed a retrospective cohort study including patients aged 0-−16 years who were treated for febrile seizures in the paediatric emergency department of a tertiary hospital over a period of 5 years. Epidemiological and clinical variables were collected. Patients were followed up for at least 2 years to confirm the final diagnosis.

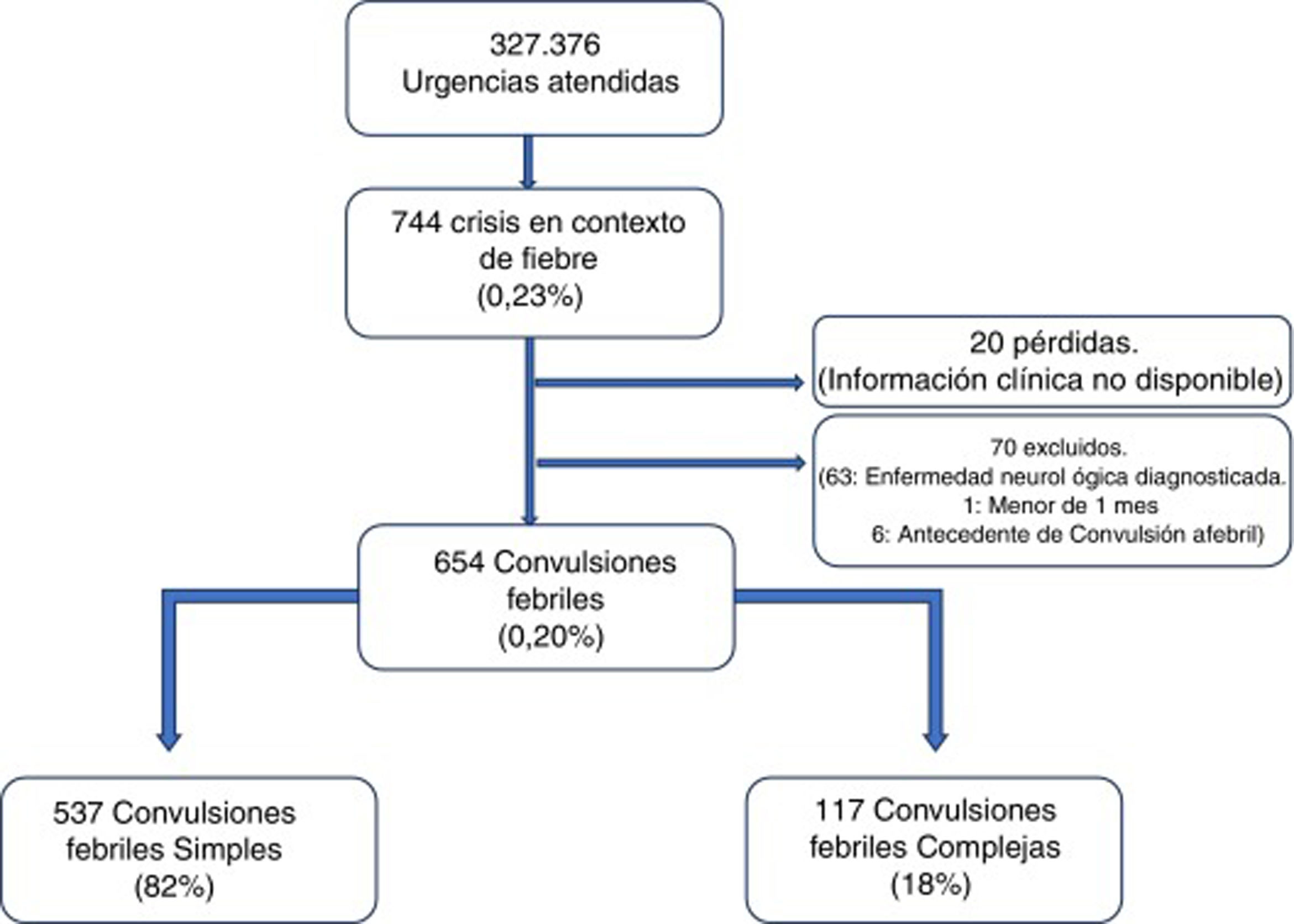

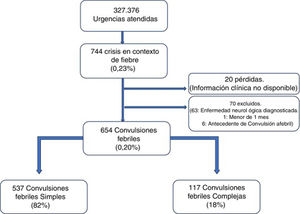

ResultsWe identified 654 patients with febrile seizures, with a prevalence of 0.20% (95% CI, 0.18-0.22); 537 (82%) had simple febrile seizures and 117 (18%) had complex febrile seizures. The clinical and epidemiological characteristics of both types were similar. Significantly more complementary tests were requested for complex febrile seizures: blood tests (71.8% vs 24.2% for simple febrile seizures), urine analysis (10.3% vs 2.4%), lumbar puncture (14.5% vs 1.5%), and CT (7.7% vs 0%). Similarly, admission was indicated more frequently (41.0% vs 6.1%). Underlying organic lesions (central nervous system infection, metabolic disease, tumour/intracranial space-occupying lesion, intoxication) were diagnosed in only 11 patients, 5 of whom had complex forms (4.3%; 95% CI, 0.6-7.9). Risk factors for developing epilepsy, identified in the multivariate analysis, were complex forms with recurrent seizures in a single attack (odds ratio [OR]: 4.94; 95% CI, 1.29-18.95), history of seizures (OR: 17.97; 95% CI, 2.26-−143.10), and seizures presenting at atypical ages (OR: 11.69; 95% CI, 1.99-68.61).

ConclusionsThe systematic indication of complementary tests or hospital admission of patients with complex febrile seizures is unnecessary. The risk of epilepsy in patients with complex forms gives rise to the need for follow-up in paediatric neurology departments.

Analizar la prevalencia, características y manejo de las convulsiones febriles simples y complejas. Secundariamente, comparar el riesgo de lesión orgánica subyacente y epilepsia entre ambos tipos de crisis y particularmente de cada subtipo que define una convulsión febril compleja.

Material y métodoEstudio de cohortes retrospectivo que incluye pacientes de 0-16 años que consultan por convulsión febril en urgencias pediátricas de un hospital terciario durante 5 años. Se recogen variables epidemiológicas y clínicas. Se realiza un seguimiento posterior mínimo de 2 años para confirmar el diagnóstico final.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 654 convulsiones febriles con una prevalencia del 0,20% (IC 95%: 0,18-0,22%), 537 fueron simples (82%) y 117 complejas (18%). Las características clínico-epidemiológicas de ambos tipos fueron similares. En las formas complejas se solicitaron significativamente más pruebas complementarias en forma de analíticas (71,8% vs. 24,2%), tóxicos (10,3% vs. 2,4%), punción lumbar 14,5% vs. 1,5%) y TAC (7,7% vs. 0%). Igualmente se indicó ingreso con mayor frecuencia (41,0% vs. 6,1%). No se diagnosticó ninguna lesión orgánica subyacente (infección del sistema nervioso central, enfermedad metabólica, tumor/lesión intracraneal ocupante de espacio, intoxicación) excepto 11 casos de epilepsia, 5 de ellas en las formas complejas (4,3%; IC 95%: 0,6-7,9%). En el análisis multivariable presentaron mayor riesgo de desarrollar epilepsia las formas complejas por ser recurrentes en el mismo proceso febril (OR: 4,94; IC 95%: 1,29-18,95), aquellos con antecedentes de crisis previas (OR: 17,97; IC 95%: 2,26-143,10) y las manifestadas a edades atípicas (OR: 11,69; IC 95%: 1,99-68,61).

ConclusionesNo está justificada la indicación sistemática de pruebas complementarias o ingreso en las convulsiones febriles complejas. El riesgo de epilepsia en las formas complejas hace necesario el seguimiento en neuropediatría.

Febrile seizures are a frequent reason for consultation with paediatric emergency departments, and constitute the most common neurological disorder in childhood, with an estimated prevalence of 2%-5% in the population aged 6 months to 5 years in the United States. Approximately 25%-35% of these are classified as complex febrile seizures (CFS).1–4

Several international clinical practice guidelines have been issued for the management of febrile seizures.3,5 Despite a certain degree of consensus regarding simple forms, CFS is more controversial, with some documents including excessively restrictive criteria, as subsequent publications have shown. Presence of CFS has classically been associated with increased risk of underlying intracranial lesions and subsequent epilepsy,6–8 with all patients with CFS routinely being admitted for assessment.3,9 However, recent studies have questioned this association and the value of emergency diagnostic tests in patients not presenting focal neurological signs after a febrile seizure.4,5,9,10 In any case, few studies have analysed the risk of complications according to the characteristics of CFS.

This study aimed to analyse the prevalence, characteristics, and management of simple febrile seizures (SFS) and CFS attended at our emergency department. As a secondary objective, we compared the risk of underlying organic lesions and epilepsy between SFS and CFS, and particularly between each subtype of CFS.

Material and methodsStudy designWe conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients aged 0 to 16 years visiting the paediatric emergency department of a tertiary hospital that receives 55 000 emergency visits per year, between January 2010 and December 2015.

The study protocol was approved by the local clinical research ethics committee and complies with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients and settingWe systematically included all patients visiting the paediatric emergency department due to seizures in the context of fever, whether seizure occurred during hospitalisation or elsewhere.

We also included patients presenting episodes that were considered febrile seizures, defined as seizures associated with a febrile disease in the absence of previously known CNS infection or electrolyte imbalance, in children older than one month with no history of afebrile seizures.11 We excluded all patients younger than one month and those with history of neurological or metabolic diseases that may promote seizures or alterations in the level of consciousness, history of afebrile seizures, or history of head trauma. We also excluded patients whose medical records did not include all the data necessary for classifying seizures as simple or complex.

Groups were defined according to the characteristics of febrile seizures,2,12 as follows:

- •

SFS: febrile seizure meeting all of the following criteria:

- o

Generalised and symmetric: tonic-clonic, tonic, or atonic

- o

Duration < 15 min

- o

Single seizure during the episode of fever

- o

Absence of neurological alterations after the episode (including Todd paralysis).

- o

- •

CFS: seizures not meeting all the criteria for SFS.

Sample size: to describe the prevalence of CFS, which is estimated at 20% of all febrile seizures (with a confidence level of 95% and precision of 3%), a total of 683 episodes of febrile seizures were necessary for our study. A review of our hospital’s records revealed that febrile seizures accounted for 0.25% of all emergencies attended in the previous year. As 55 000 annual visits would include 138 episodes of febrile seizures, 273 200 visits (5 years) were deemed to be necessary to reach the desired sample size.

Study variablesWe reviewed the clinical histories of the patients included and our regional healthcare service’s clinical history database, which includes all primary and specialised care records, for a minimum of 2 years.

The following variables were recorded for each case:

- •

Demographic variables. Date of consultation, age (typical vs atypical age, with typical age defined as 6 months to 6 years, as reported in the literature), sex, personal history of seizures, seizure characteristics.

- •

Clinical variables. Signs and symptoms: fever (time from onset of fever to seizure, focus of infection), seizure characteristics (duration, presence and duration of postictal period, focal neurological signs during and after the seizure, recurrence within 24 hours), time to treatment (from onset of seizure to attention at the emergency department), treatment during the episode (drug, dose), complementary tests performed at the emergency department (blood analysis, toxicology test, lumbar puncture, neuroimaging studies [CT]), and clinical progression (need for admission, need for follow-up by the paediatric neurology department for a minimum of 2 years after the episode).

- •

Outcome variables. Final diagnosis: healthy; presence of an underlying organic lesion explaining the episode, diagnosed at discharge from the emergency department, after hospitalisation, at another centre, or during follow-up by primary or specialised care (including CNS infection, metabolic disease, intracranial space-occupying lesion or tumour, toxicity); or epilepsy diagnosed during follow-up by the paediatric neurology department.

The SPSS software (version 20.0) was used for the statistical analysis.

Continuous variables following a normal distribution are presented as means and standard deviation (SD), whereas non–normally distributed variables are presented as medians and quartiles 1 and 3 (Q1-–Q3). Normal distribution was tested with histograms and Q-Q plots. Qualitative variables are presented as absolute frequencies and percentages.

Associations between qualitative variables were determined with the chi square test or the Fisher exact test, and associations between quantitative variables were analysed with the t test or the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test.

The risk of underlying organic lesions was calculated with univariate and multivariate analyses, using logistic regression models. For the multivariate analysis, we created explanatory models initially including all variables, and subsequently eliminated those with P-values > .10 in a stepwise manner. We quantified the risk of underlying organic lesions with odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI). Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

ResultsA total of 327 376 emergencies were attended during the study period, 744 of which corresponded to episodes of seizures associated with fever (0.23%; 95% CI, 0.21-0.24). Our study included 654 episodes of febrile seizures, representing a prevalence of 0.20% (95% CI, 0.18-0.22). No patient was excluded due to history of metabolic disease, CNS infection, or space-occupying intracranial lesions, or due to incomplete data. Although 35 records did not specify seizure duration in minutes, it was possible in all cases to determine whether seizures lasted more or less than 15 minutes, and therefore to classify seizures based on this criterion.

Fig. 1 shows the selection process.

Characteristics of febrile seizuresWe included 537 patients with SFS (0.16%; 95% CI, 0.15-−0.18), accounting for 82% of all febrile seizures, and 117 with CFS (0.04%; 95% CI, 0.03-0.04), which accounted for the remaining 18%. Age ranged from 4.6 months to 9.7 years. The CFS group included 46 patients with prolonged seizures (39.3%), 6 with non-generalised seizures (5.1%), 76 presenting seizure recurrence within 24 hours (65.0%), and 8 patients presenting focal neurological signs after the episode (6.8%); some seizures presented more than one of these characteristics.

Median age of the patients with SFS was 23.0 months (Q1-Q3: 16.5-33.4); boys accounted for 61.5% of this group. Patients in the CFS subgroup had a median age of 22.7 months (Q1-Q3: 16.1-29.8) (P = .561), with 66.7% being boys (P = .291). A total of 227 patients (34.7%) had history of febrile seizures, 181 (33.7%) had history of SFS, and 46 (39.3%) had history of CFS (P = .248). The most frequent type of seizure in both groups was tonic-clonic seizures, accounting for 340 cases of SFS (63.3%) and 76 cases of CFS (65.0%), followed by tonic seizures (22.9% vs 18.8%) and atonic seizures (13.8% vs 11.1%). The focus of infection was identified in 441 patients with SFS (82.1%) and in 97 patients with CFS (82.9%); the respiratory tract was the most frequent focus of infection in both groups (65.1% and 55.7%, respectively).

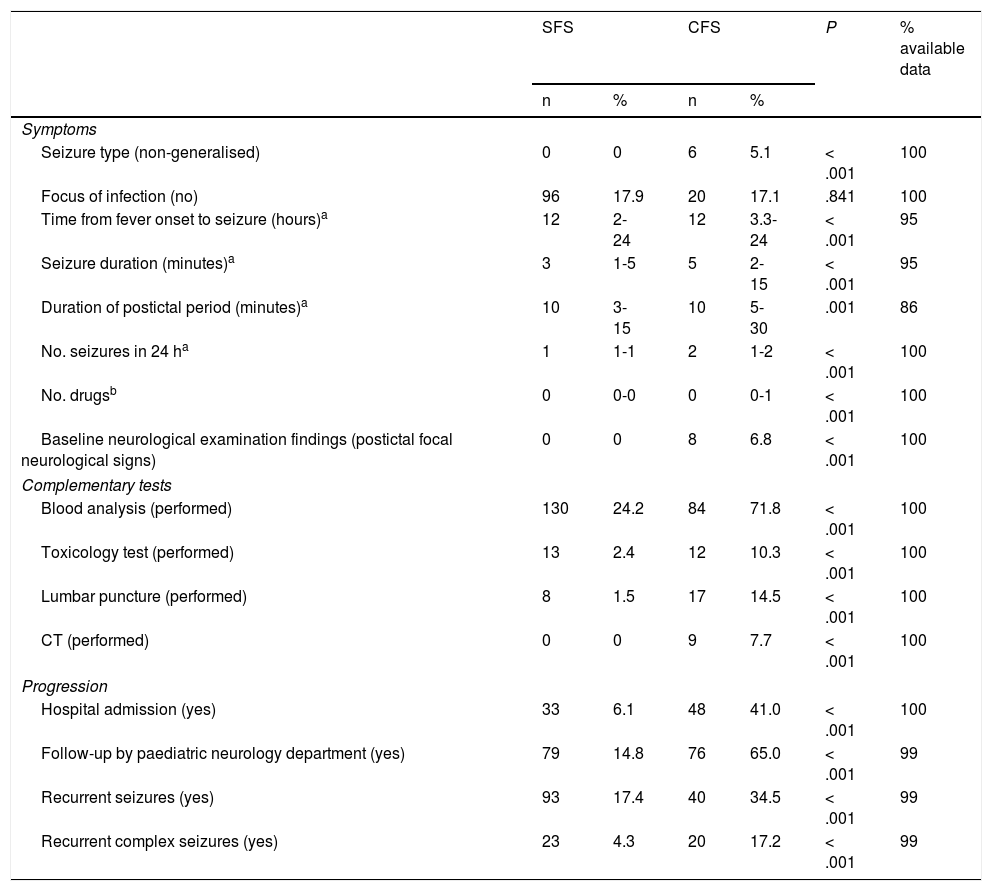

The time interval between onset of fever and seizure was longer in patients with CFS; these seizures also lasted longer and presented a longer postictal period, greater likelihood of recurrence within 24 hours, and greater frequency of focal neurological signs after the episode (Table 1).

Clinical characteristics, management, and progression of simple and complex febrile seizures.

| SFS | CFS | P | % available data | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Symptoms | ||||||

| Seizure type (non-generalised) | 0 | 0 | 6 | 5.1 | < .001 | 100 |

| Focus of infection (no) | 96 | 17.9 | 20 | 17.1 | .841 | 100 |

| Time from fever onset to seizure (hours)a | 12 | 2-24 | 12 | 3.3-24 | < .001 | 95 |

| Seizure duration (minutes)a | 3 | 1-5 | 5 | 2-15 | < .001 | 95 |

| Duration of postictal period (minutes)a | 10 | 3-15 | 10 | 5-30 | .001 | 86 |

| No. seizures in 24 ha | 1 | 1-1 | 2 | 1-2 | < .001 | 100 |

| No. drugsb | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-1 | < .001 | 100 |

| Baseline neurological examination findings (postictal focal neurological signs) | 0 | 0 | 8 | 6.8 | < .001 | 100 |

| Complementary tests | ||||||

| Blood analysis (performed) | 130 | 24.2 | 84 | 71.8 | < .001 | 100 |

| Toxicology test (performed) | 13 | 2.4 | 12 | 10.3 | < .001 | 100 |

| Lumbar puncture (performed) | 8 | 1.5 | 17 | 14.5 | < .001 | 100 |

| CT (performed) | 0 | 0 | 9 | 7.7 | < .001 | 100 |

| Progression | ||||||

| Hospital admission (yes) | 33 | 6.1 | 48 | 41.0 | < .001 | 100 |

| Follow-up by paediatric neurology department (yes) | 79 | 14.8 | 76 | 65.0 | < .001 | 99 |

| Recurrent seizures (yes) | 93 | 17.4 | 40 | 34.5 | < .001 | 99 |

| Recurrent complex seizures (yes) | 23 | 4.3 | 20 | 17.2 | < .001 | 99 |

CFS: complex febrile seizures; SFS: simple febrile seizures. Values are expressed as absolute numbers (n) and percentages (%) for each seizure type.

Non-generalised: partial, partial onset with secondary generalisation.

Patients with CFS more frequently required antiepileptic drugs (39.3%, vs 11.4% of patients with SFS) and underwent a greater number of complementary tests (Table 1). Blood analyses were performed in 130 patients from the SFS group (24.2%), showing abnormal results in 83 cases (63.8%, of which 85.5% presented high levels of acute phase reactants, 12.0% presented ion/glycaemic alterations, and the remaining patients presented other nonspecific alterations). In the CFS group, 84 patients (71.8%) underwent blood analyses, with 58 of these (69.0%) showing alterations (79.3% presented high levels of acute phase reactants, 19.0% presented ion/glycaemic alterations, and the remaining patients presented other nonspecific alterations). All metabolic alterations were mild and transient, resolving without intervention, and elevations in levels of acute phase reactants were not associated with CNS infection in any case. The urine toxicology test detected benzodiazepines in one case; the patient had received treatment with these drugs during the episode. All CSF analyses yielded negative results. None of the patients with SFS underwent emergency neuroimaging studies, whereas 9 patients with CFS (7.7%) underwent emergency CT scans, which revealed no alterations in any case.

Five patients with CFS were admitted to the paediatric intensive care unit, due to status epilepticus in all cases; none of the patients with SFS required admission.

All admissions were either due to infection or due to family concerns. However, 6 of the 43 patients admitted to hospital with CFS were admitted due to convulsive status epilepticus, 26 due to the occurrence of more than one seizure, 3 due to infection, and 8 for observation.

After the episode motivating study inclusion, 20 patients with CFS (17.1%) presented additional episodes of complex seizures and 20 presented additional simple seizures. In the SFS group, in contrast, 23 patients (4.3%) subsequently presented complex seizures, and 70 (13.0%) presented simple seizures.

Clinical, management, and prognostic data are summarised in Table 1.

Seizure aetiologyNone of the patients presented underlying organic lesions, including CNS infection, space-occupying lesions, toxicity, or metabolic disorders.

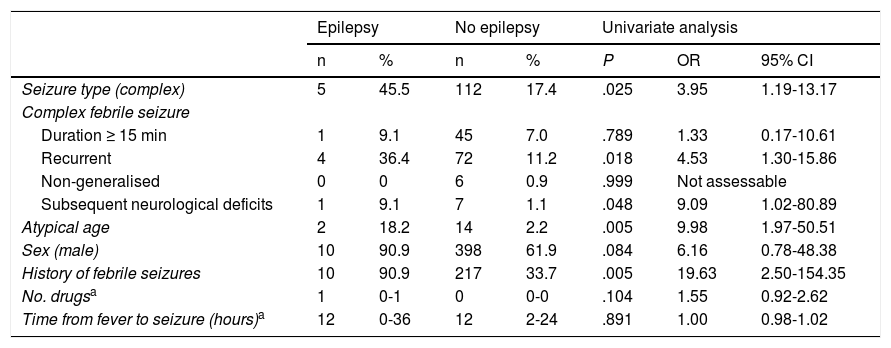

During follow-up (range, 2-7 years), 11 patients were diagnosed with epilepsy: 5 patients from the CFS group (4.3%; 95% CI, 0.6-7.9) and 6 from the SFS group (0.9%; 95% CI, 0.2-2.0).

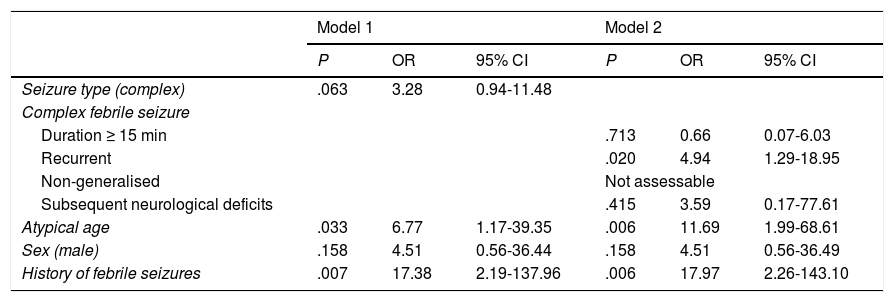

We created 2 logistic regression models with the variables that had displayed an association with subsequent development of epilepsy, with at least a trend toward statistical significance (P < .10), in the univariate analysis (Table 2). The analysis showed a high risk of epilepsy in patients with atypical ages, history of febrile seizures, and presenting CFS, particularly those presenting more than one episode within 24 hours (Table 3).

Risk factors for developing epilepsy. Univariate analysis.

| Epilepsy | No epilepsy | Univariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | P | OR | 95% CI | |

| Seizure type (complex) | 5 | 45.5 | 112 | 17.4 | .025 | 3.95 | 1.19-13.17 |

| Complex febrile seizure | |||||||

| Duration ≥ 15 min | 1 | 9.1 | 45 | 7.0 | .789 | 1.33 | 0.17-10.61 |

| Recurrent | 4 | 36.4 | 72 | 11.2 | .018 | 4.53 | 1.30-15.86 |

| Non-generalised | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0.9 | .999 | Not assessable | |

| Subsequent neurological deficits | 1 | 9.1 | 7 | 1.1 | .048 | 9.09 | 1.02-80.89 |

| Atypical age | 2 | 18.2 | 14 | 2.2 | .005 | 9.98 | 1.97-50.51 |

| Sex (male) | 10 | 90.9 | 398 | 61.9 | .084 | 6.16 | 0.78-48.38 |

| History of febrile seizures | 10 | 90.9 | 217 | 33.7 | .005 | 19.63 | 2.50-154.35 |

| No. drugsa | 1 | 0-1 | 0 | 0-0 | .104 | 1.55 | 0.92-2.62 |

| Time from fever to seizure (hours)a | 12 | 0-36 | 12 | 2-24 | .891 | 1.00 | 0.98-1.02 |

Values are expressed as absolute numbers (n) and percentages (%) for presence or absence of subsequent epilepsy. Some febrile seizures may be classed as complex for more than one reason.

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

Atypical age: age younger than 6 months or older than or equal to 6 years.

No. drugs: drugs needed for the treatment of the active seizure.

Adjusted risk factors for developing epilepsy. Multivariate analysis.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | |

| Seizure type (complex) | .063 | 3.28 | 0.94-11.48 | |||

| Complex febrile seizure | ||||||

| Duration ≥ 15 min | .713 | 0.66 | 0.07-6.03 | |||

| Recurrent | .020 | 4.94 | 1.29-18.95 | |||

| Non-generalised | Not assessable | |||||

| Subsequent neurological deficits | .415 | 3.59 | 0.17-77.61 | |||

| Atypical age | .033 | 6.77 | 1.17-39.35 | .006 | 11.69 | 1.99-68.61 |

| Sex (male) | .158 | 4.51 | 0.56-36.44 | .158 | 4.51 | 0.56-36.49 |

| History of febrile seizures | .007 | 17.38 | 2.19-137.96 | .006 | 17.97 | 2.26-143.10 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

Model 1: risk of developing epilepsy in patients with complex febrile seizures, as compared to those with simple febrile seizures, adjusted for sex, age, and personal history of seizures.

Model 2: risk of developing epilepsy for each subtype of complex febrile seizures, as compared to the other subtypes, adjusted for sex, age, and personal history of seizures.

Atypical age: younger than 6 months or 6 years or older.

Our study is the first comprehensive review of the prevalence and characteristics of SFS and CFS in our setting, and also describes the risk of developing epilepsy by subtype of CFS.

We found one case of febrile seizures for every 500 visits to the emergency department, concluding that this is a relatively frequent reason for consultation. The proportion of SFS and CFS in our sample was similar to those reported for other developed countries.13,14

Although we observed no clinical or demographic differences between patients with SFS and those with CFS (except in the features characterising CFS), management of these 2 types of seizures at the emergency department differed considerably. This has also been observed in other studies including patients with CFS.8,15,16

The action protocol for SFS at the emergency department is well established, based on the available evidence3,5,12; however, emergency management of CFS is controversial. While some studies recommend performing analyses to rule out other causes of seizures, such as electrolyte imbalances, hypoglycaemia, or invasive bacterial infection,3,14,17 others suggest that these tests should not be performed routinely but rather should be limited to patients with clinical suspicion of any of these alterations.2,5,15,18 In our study, complementary analyses were performed for nearly three-quarters of all patients with CFS. Our results reveal no relevant alterations aside from the underlying infectious process; therefore, complementary tests should exclusively aim to determine the focus of infection, or be based on clinical suspicion.

One of the main concerns surrounding CFS is the possibility that the episode may be secondary to meningitis or encephalitis. Lumbar puncture in these patients has also been a controversial subject. According to the most recent reviews, lumbar puncture is not necessary after an episode of CFS in children presenting no symptoms of meningitis.5,10 Kimia et al.10 and Seltz et al.16 reported bacterial meningitis in 0.9% and 1.5% of patients, respectively; the most frequent pathogen was pneumococcus. In our sample, few patients underwent lumbar puncture, and all CSF analyses yielded negative results. Had these analyses yielded positive results, the prevalence of meningitis would have been 0.2% (95% CI, 0-0.5) of all episodes and 0.9% (95% CI, 0-2.5) of all cases of CFS. These low rates may be explained by systematic vaccination with the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in our autonomous community since 2006. These data support the latest recommendations of the American Academy of Pediatrics.5

To date, no association has been found between CFS and pathological intracranial lesions4,19; therefore, systematic emergency neuroimaging studies are not recommended. The largest series of children presenting a first episode of CFS and undergoing neuroimaging studies included 268 patients; only 4 showed alterations in neuroimaging studies, and 3 of these presented alterations in the neurological examination.4 Few patients in our series underwent emergency CT studies (only those presenting focal neurological signs after the episode); no alterations were observed in any case.

Published rates of hospital admission due to CFS range from 47% to 57%4,9,16; similar rates were found in our study. Systematic admission for observation and assessment seems not to be justified in patients with no underlying organic lesions9; rather, it should only be considered in selected cases, based on the patient’s medical history and complementary test results.

During follow-up by the paediatric neurology department, 11 patients were diagnosed with epilepsy, with significantly higher prevalence among patients with CFS, in line with previous observations. Presenting CFS seems to be independently associated with increased risk of epilepsy (trend toward significance, adjusted for age, sex, and history of febrile seizures); however, recurrent seizures during the same episode of fever seem to be the only CFS subtype presenting a higher risk of epilepsy.19–21 As other researchers have proposed,17,18 history of febrile seizures or presentation at atypical ages constitute the main predictors of epilepsy.

ConclusionsOur study has several limitations, mainly its retrospective design and the fact that the sample was drawn from a single centre. No underlying organic lesions were detected in any patient; we are therefore unable to provide a precise estimate of their prevalence. Likewise, the small number of patients diagnosed with epilepsy prevents us from determining the adjusted risk for each subtype of CFS. Furthermore, we cannot compare the risk of developing epilepsy in our population against that of the general population, since our sample did not include children without febrile seizures; however, SFS have been reported to increase the relative risk by 1%.6 Patient follow-up data were gathered from our regional healthcare service’s clinical history database. Therefore, our study does not include data from consultations at centres that do not upload clinical data to this database (eg, private centres), except when patients’ paediatricians are informed of any consultation with private centres, in which case paediatricians would indicate this on the patient’s medical history.

According to our results, systematic complementary testing or hospital admission of patients with CFS is not justified; the decision to do so should be made on a case-by-case basis. We recommend follow-up by the paediatric neurology department due to the increased risk of epilepsy, particularly in patients with history of febrile seizures, those younger than 6 months or older than 6 years, and those with complex seizures (more than one seizure during the same episode of fever).

Multicentre studies including patients with more complications are needed to provide a more precise estimate of the risks associated with febrile seizures.

FundingThis study has received no funding of any kind. None of the authors has received any fees for their role in the study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Rivas-García A, Ferrero-García-Loygorri C, Carrascón González-Pinto L, Mora-Capín AA, Lorente-Romero J, Vázquez-López P. Convulsiones febriles simples y complejas, ¿son tan diferentes? Manejo y complicaciones en urgencias. Neurología. 2022;37:317–324.