Neuropaediatricians manage patients from the neonatal period through adolescence and youth. Whenever their patients are not discharged, sooner or later they must be transferred to adult physicians: family physicians, neurologists, neurosurgeons or other specialists.

This transfer is necessary because neuropaediatricians are experts in children and adolescents but not in adults. Moreover, it is inappropriate for adults to be treated in paediatric wards.

However, this transfer can be traumatic because, in some cases, a relationship has existed for many years. This includes both the way of working and the affection established between neuropaediatricians and patients and their families, who must adapt to new environments and new professionals. Furthermore, neurologists are not always prepared to deal with some neuropaediatric diseases.

The issue of transfers was raised for the first time in the United States, at a convention which took place in 1984, as a result of the significant increase in survival in children with chronic and disabling conditions during the 1970s and 1980s. Subsequently, there have been 2 other conventions in 1989 and 2001.1

A search in PubMed, dated February 13th, 2011, for reviews containing the terms “pediatric to adult transition”, returned 130 articles (of which only 8 were from the 20th century) related to cystic fibrosis, cancer, transplants, congenital heart disease, diabetes mellitus, inflammatory bowel disease, chronic kidney disease, growth hormone deficiency and neurological and neurosurgical pathology.

In total, 12 articles made reference to neurological problems concerning unspecified neurological diseases,2 miopathies,3 hydrocephalus,4 CNS tumours,5 attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),6 neurosurgical pathology,7–9 brain trauma,10 phacomatosis and genetically determined tumours,11 spina bifida12,13 and cerebral palsy.13 In addition, 1 review made reference to inborn errors of metabolism,14 many of which have a neurological effect. Until recently, their diagnosis and follow-up corresponded to paediatricians, but, at present, adult services (especially neurology and internal medicine) must also adapt to them.15

All the articles agree that very little progress has been made and highlight a number of barriers for a successful transition: lack of coordination between paediatric and adult units, problems related to parents, family and patient resistance, lack of planning and lack of institutional support.

Neuropaediatricians deal with:

- –

Problems of low fragility and high prevalence, such as headaches, some non-epileptic paroxysmal disorders, some epilepsies and ADHD.

- –

Problems of high fragility (taken into account separately, although together they represent a large number of patients), lower prevalence, and with a high personal, family and social impact, such as pathological psychomotor retardation (including autism spectrum disorders and mental retardation), cerebral palsy, tumoural pathology, metabolic diseases, neuromuscular unit diseases, spinal disorders including myelomeningocele, refractory epilepsy and neurocutaneous syndromes. Over 8% of our patients suffer rare diseases (with an established diagnosis) and over 8% suffer epilepsies, of which over 20% are refractory.16

We reviewed our experience at Hospital Miguel Servet in Zaragoza for a period of 20 years, from May 1990 to November 2010.16–18 The paediatric neurology database contained 13268 patients from that period, of which 855 (6.4%) were over 14 years of age at the time of last modification: 361 were aged 14 years, 170 were aged 15 years, 103 were aged 16 years, 86 were aged 17 years, 72 were aged 18 years and 62 were aged 19 to 28 years. Of these 855 patients, 274 (32%) continued to be managed by the neuropaediatric unit, 11 (1.2%) died, 353 (41.2%) were discharged (that is, transferred to the care of their family doctor) and 151 (17.6%) were transferred to adult neurology units.

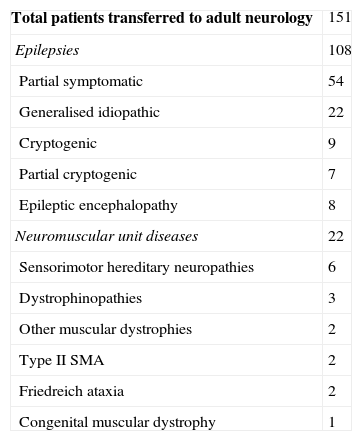

The pathologies suffered by patients who were transferred to adult neurology units were 108 cases of epilepsy and 22 neuromuscular unit diseases (Table 1). The diagnoses of the 353 children who were discharged and, therefore, transferred to their family doctors, included 35 cases of mental retardation, 26 cases of cerebral palsy, 18 cases of ADHD, 6 cases of type 1 neurofibromatosis and 2 cases of autism spectrum disorders.

Diagnoses of the 151 patients transferred from a neuropaediatric unit to an adult neurology service.

| Total patients transferred to adult neurology | 151 |

| Epilepsies | 108 |

| Partial symptomatic | 54 |

| Generalised idiopathic | 22 |

| Cryptogenic | 9 |

| Partial cryptogenic | 7 |

| Epileptic encephalopathy | 8 |

| Neuromuscular unit diseases | 22 |

| Sensorimotor hereditary neuropathies | 6 |

| Dystrophinopathies | 3 |

| Other muscular dystrophies | 2 |

| Type II SMA | 2 |

| Friedreich ataxia | 2 |

| Congenital muscular dystrophy | 1 |

SMA: spinal muscular atrophy.

The neurology and neuropaediatric services and the managers responsible should make an effort to improve the transfer through a transition process, which could be established through different approaches. There are some pathologies which can and should be managed by paediatricians and primary care physicians, others which should be transferred to neurosurgery and, perhaps, psychiatry services, and yet others which should be transferred to neurology services.

Currently, there is no dispute about the need for experts in 2 age groups: neuropaediatricians and neurologists. The figure of an expert in the transition age group (and, therefore, “expert in transition”) could also be very useful.

An “expert in transition” would be a prime tool to implement communication and teamwork between neuropaediatricians, neurologists and neurosurgeons. All have much to learn from each other and communication should be fostered through joint meetings and the use of information and communication technology (especially e-mail).

The keys to a successful transition are:

- –

The transfer should be announced previously.

- –

There should be a perception of continuity by users, of being part of the same team, with the same criteria and work methodology.

- –

Planning.

- –

Institutional support.

Neurology services in Spain generally have more neurologists than neuropaediatric units. Neuropaediatricians are too few to share the burden of healthcare and permanent update in very diverse fields (many of them complex and with continuous advances). Neurology services could share a neurologist with neuropaediatric units (“part-time donation”), ideally one suitable as a neuropaediatrician after 2 years of training at a neuropaediatric unit. This neurologist–neuropaediatrician could alternate between healthcare, teaching, neurology research and management, neuropaediatric and “transition” duties.

In conclusion, neuropaediatric patients should be transferred to adult physicians between the ages of 14 and 18 years, ideally through a transition process led by a neurologist–neuropaediatrician. This professional would rapidly become an expert in such transitions and a key figure in the communication between neurology and neuropaediatric units, as well as in the training of neurologists for problems which they are not used to, including neurocutaneous syndromes, mental retardation, autism spectrum disorders, childhood cerebral palsy, ADHD and metabolic diseases. Ultimately, quality and continuity of care would improve to the benefit of patients, their families and professionals, who would be satisfied by the improvement of their service.

Please cite this article as: López Pisón J, et al. La transferencia de neuropediatría a medicina de adultos. Neurología. 2012;27:183–5.