Recent studies conducted in Europe and the United States suggest upward trends in both incidence and hospitalisation rates for ischaemic stroke in young adults; however, data for Spain are scarce. This study analyses the trend in hospitalisation due to ischaemic stroke in adults aged under 50 years in the region of Murcia between 2006 and 2014.

MethodWe performed a retrospective study of patients discharged after hospitalisation due to cerebrovascular disease (CVD); data were obtained from the regional registry of the Minimum Basic Data Set. Standardised rates were calculated, disaggregated by age and CVD subtype. Time trends were analysed using joinpoint regression to obtain the annual calculated standardised rate and the annual percentage of change (APC).

ResultsA total of 27 064 patients with CVD were discharged during the 9-year study period. Ischaemic stroke was the most frequent subtype (61.0%). In patients aged 18 to 49 years, the annual number of admissions due to ischaemic stroke increased by 26%, and rates by 29.2%; however, the joinpoint regression analysis showed no significant changes in the trend (APC = 2.74%, P ≥ .05). By contrast, a downward trend was identified in individuals older than 49 (APC = –1.24%, P < .05).

ConclusionsNo significant changes were observed in the rate of hospitalisation due to ischaemic stroke among young adults, despite the decline observed in older adults. Identifying the causes of these disparate trends may be beneficial to the development of specific measures targeting younger adults.

Estudios recientes en Europa y Estados Unidos muestran un posible aumento de la incidencia y hospitalización por ictus isquémico en adultos jóvenes, sin embargo en España la información disponible de la tendencia es escasa. Por ello planteamos analizar la tendencia de hospitalización por ictus isquémico en adultos menores de 50 años en la Región de Murcia entre 2006 y 2014.

MétodoSe realizó un estudio retrospectivo de las altas de hospitalización por patología cerebrovascular (PCV) extraídas del Registro del Conjunto Mínimo de Datos al Alta Hospitalaria. Se obtuvieron las tasas estandarizadas, desagregadas según edad y subtipo de PCV. La tendencia de los episodios fue analizada mediante regresión de Joinpoint, obteniendo la tasa estandarizada anual calculada y el porcentaje de cambio anual (PCA).

ResultadosSe identificaron un total de 27.064 altas por PCV en los 9 años del estudio. Los episodios generados por ictus isquémico fueron los más numerosos (61,0%), en pacientes entre 18 y 49 años, entre los años extremos, se registró un aumento del 26% de los episodios por ictus isquémico y del 29,2% de las tasas, mientras que en la regresión de Joinpoint no se observó tendencia (PCA = 2,74%, p ≥ 0,05). Por el contrario, en mayores de 49 años esta tendencia fue descendente (PCA = −1,24%, p < 0,05).

ConclusionesNo se ha identificado una tendencia en la hospitalización por ictus isquémico en adultos jóvenes a pesar del descenso en adultos de mayor edad. Sería importante identificar las causas de este comportamiento desigual para desarrollar medidas específicas dirigidas al grupo de menor edad.

According to data from the World Health Organization, cerebrovascular disease (CVD) is the second leading cause of death worldwide.1 A study into the global burden of disease in Spain found that CVD was the third leading specific cause of death in 2016, after ischaemic heart disease and Alzheimer disease and other dementias.2 In Spain, 3.5% of all disability-adjusted life years (DALY) were attributed to CVD, and specifically ischaemic stroke, in approximately half of these.3

Although the risk of stroke increases with age, CVD in young adults may have a greater impact socioeconomically and in terms of DALYs.4 Studies conducted recently in Europe and the United States reveal an increase in the frequency of ischaemic stroke in young adults.5–14 In our setting, however, little evidence is available on the incidence of ischaemic stroke in this age group.10 Furthermore, the incidence and management of ischaemic stroke in young adults varies between regions,10,15,16 which makes it difficult to extrapolate the results obtained in other geographical areas.

The objective of this study is to analyse hospitalisation trends in young adults (< 50 years) presenting ischaemic stroke in the region of Murcia between 2006 and 2014.

Material and methodsStudy design and population: we conducted a retrospective study of hospital discharges of patients with CVD between 2006 and 2014. Data were gathered from the minimum basic dataset of the Region of Murcia’s Department of Health. This registry includes clinical and administrative information on the activities of all hospitals in the region. Hospital discharge data were coded by trained professionals, most of whom are technicians specialised in health data coding and belong to the coding department of each centre. We selected patients whose main diagnosis at discharge corresponded to the codes used in the Spanish National Health System’s stroke care strategy,17 based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM), who were residents of the region of Murcia and had been hospitalised in public or private non-profit hospitals (that is, patients whose management was covered by public funds). Personal data were anonymised.

To minimise overestimation of the number of cases, we combined consecutive discharges occurring during the same management process due to inter-hospital patient transfer to obtain a single, complete record. We excluded long-stay hospitalisations, defined as patients managed at long-stay centres or those staying at hospital for longer than 90 days.

We gathered demographic (age, sex) and clinical data (main diagnosis, diagnostic intensity). Based on the codes recorded for the main diagnosis, we grouped patients into the following categories: ischaemic stroke (433. × 1 and 434. × 1), haemorrhagic stroke (430.XX to 432.XX), and transient ischaemic attack (TIA; 435.XX). Based on the methods used in previous studies,18 we established 2 age groups: young adults (18-49 years) and older adults (≥ 50 years). Diagnostic intensity, expressed as annual rate per 100 complete episodes, was calculated for the following tests: computerised axial tomography of the head (ICD-9-CM codes 87.03 and 87.04), magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and brainstem (88.91), arteriography of the cerebral arteries (88.41), and diagnostic ultrasound of the head and neck (88.71).

The annual hospitalisation rate was calculated using mid-year population estimates, by arithmetic interpolation based on the local register of residents.19 We also calculated age- and sex-adjusted rates (standardised rates) using the direct method and the European Standard Population.20 Rates are expressed as number of cases per 100 000 population.

The region of Murcia had 1 467 053 inhabitants in 2014,19 with a stable population (mean annual growth of 0.75% during the study period), and 9 easily accessible public general hospitals.

Descriptive analyses were completed using the SPSS software, version 21.0 (IBM Corp; Armonk, NY, USA). The trend in hospitalisation due to CVD and its subtypes was evaluated with joinpoint regression analysis (grid-search method) using the statistical software provided by the US National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance Research Program (version 4.6.0.0).21,22 To this end, we used annual standardised rates, which are represented by dots on our graphs (Figs. 1 and 2, and Fig. A.1 of Supplementary material). Based on these rates, we estimated: (1) the calculated annual rates, represented by a line on the graph (Figs. 1 and 2, and Fig. A.1 of Supplementary material), and (2) the annual percentage change (APC) of the calculated rates, with 95% confidence intervals. The APC value indicates whether the trend was upward (+) or downward (–), and the magnitude of the trend year by year (expressed as a percentage of the rate). APC may be constant for the whole period; however, when the trend changes within the study period (joinpoints), different APC values are obtained, one for each segment. Joinpoint analysis allowed us to detect whether the trend was statistically significant (eg, CVD rates were increasing or decreasing) or non-significant (eg, CVD rates remained stable), and the presence of inflection points (joinpoints) in the trend. Hypothesis testing aimed to detect whether the slope of the trend line was statistically different from 0 (upward/downward trend) and whether significant changes (joinpoints) in the trend occurred during the study period. Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

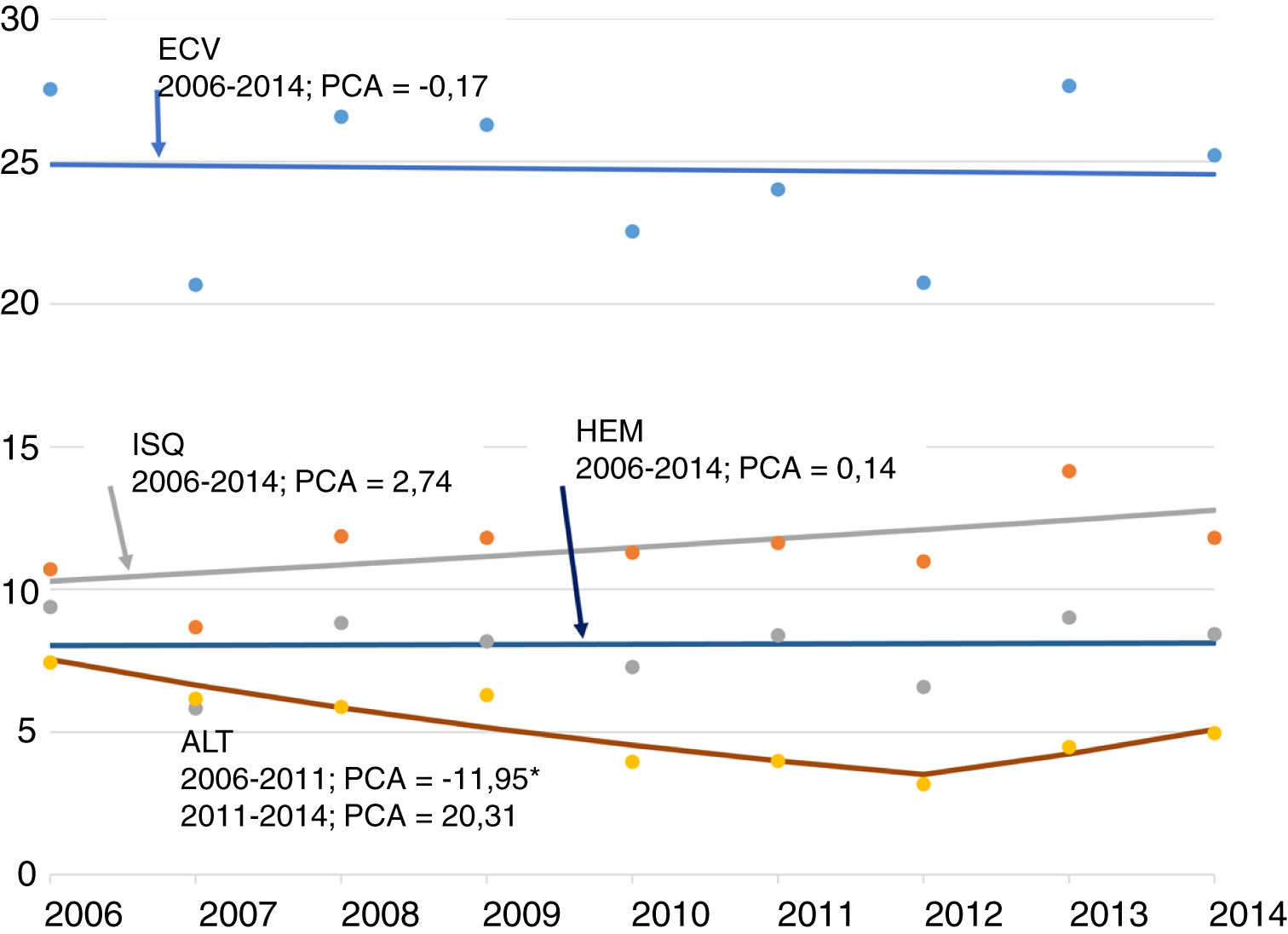

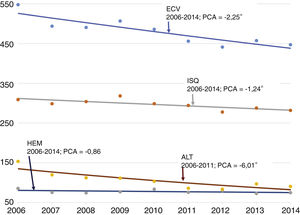

Trend of cerebrovascular disease episodes in patients aged 18-49 years. Standardised rate (European Standard Population): number of episodes per 100 000 population (region of Murcia, 2006-2014).

Dots: values observed (standardised rates). Line: trend (calculated rates). Negative numbers: negative APC. Positive numbers: positive APC.

Statistically significant results: an inflection point (joinpoint) was detected in the trend of hospitalisations due to TIA in 2012. During the 2006-2012 period, the hospitalisation rate decreased by a mean of 11.95% per year.

APC: annual percentage change; CVD: cerebrovascular disease; HS: haemorrhagic stroke; IS: ischaemic stroke; TIA: transient ischaemic attack.

*Statistically significant trend (P < .05).

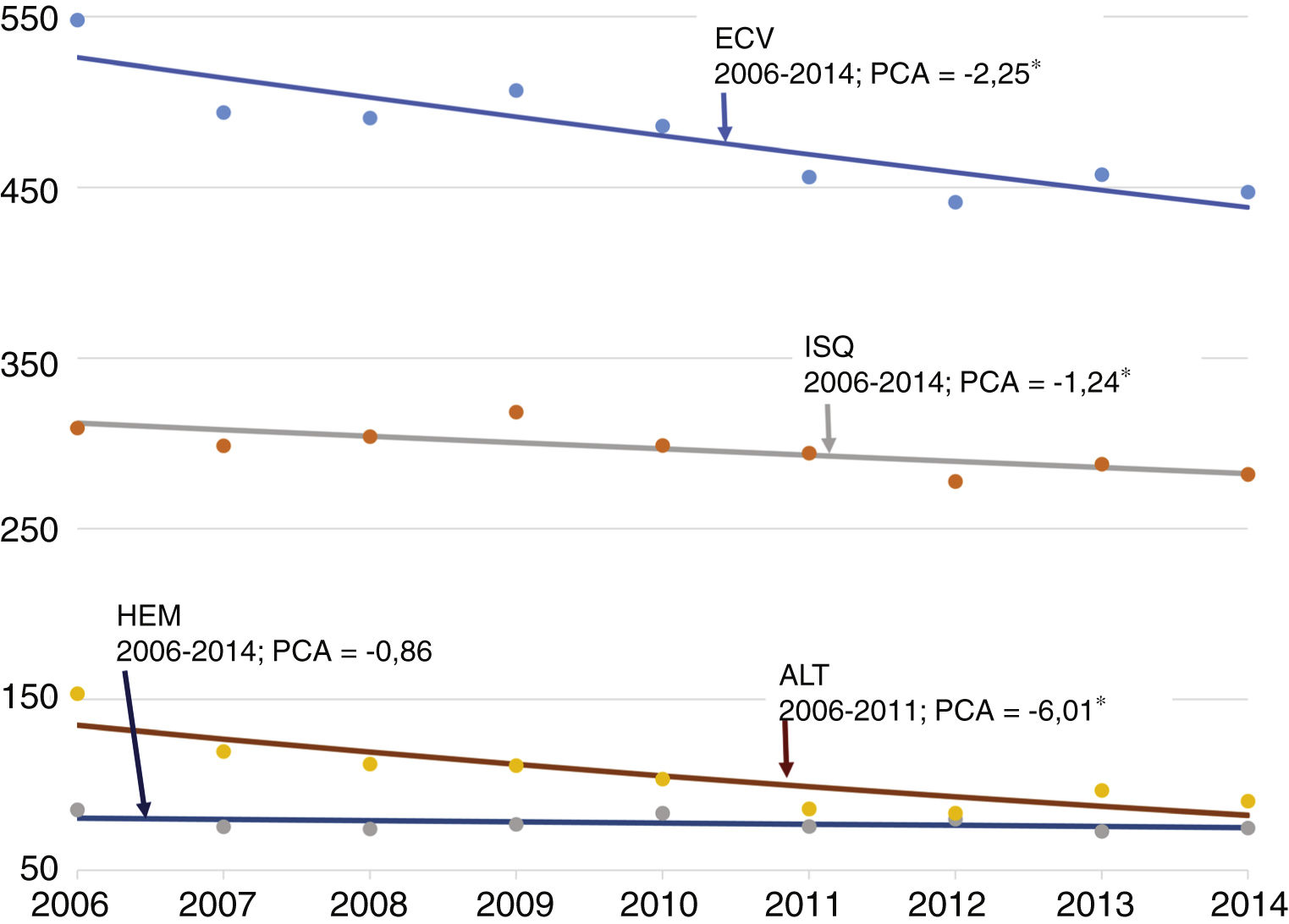

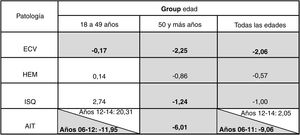

Trend of cerebrovascular disease episodes in patients aged 50 years or older. Standardised rate (European Standard Population): number of episodes per 100 000 population (region of Murcia, 2006-2014).

Dots: values observed (standardised rates). Line: trend (calculated rates). Negative numbers: negative APC.

Statistically significant results: the rates of cerebrovascular disease, ischaemic stroke, and transient ischaemic attack decreased by a mean of 2.25%, 1.24%, and 6.01%, respectively, per year. No joinpoints were detected in the trend.

APC: annual percentage change; CVD: cerebrovascular disease; HS: haemorrhagic stroke; IS: ischaemic stroke; TIA: transient ischaemic attack.

*Statistically significant trend (P < .05).

From 2006 to 2014, a total of 27 064 patients with CVD were discharged, corresponding to 25 346 complete episodes (Table 1 of Supplementary material). Due to patient transfers between hospitals, a total of 1.07 discharges were recorded per episode. This phenomenon increased with time, and was more common among younger patients and those with haemorrhagic stroke and less common among patients with TIA.

The most frequent CVD episodes were ischaemic strokes (61.0%), followed by TIAs (22.1%) and haemorrhagic strokes (17.0%) (Table 1 and Tables 1-3 of Supplementary material). More than half of episodes were recorded in men, with a mean age of around 70 years, which remained stable throughout the study period.

Hospital discharges due to ischaemic stroke by age group (2006-2014), in the region of Murcia.

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ||||||||||

| Complete episodes | 1605 | 1581 | 1680 | 1797 | 1770 | 1782 | 1692 | 1783 | 1759 | 15 449 |

| Discharges | 1640 | 1623 | 1738 | 1894 | 1878 | 1909 | 1856 | 1963 | 1947 | 16 448 |

| Discharges per complete episode | 1.02 | 1.03 | 1.03 | 1.05 | 1.06 | 1.07 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.11 | 1.06 |

| Age (years), mean | 73.5 | 73.9 | 73.8 | 73.4 | 74.6 | 74.3 | 74.0 | 73.1 | 73.8 | 73.8 |

| Age (years), median | 75.0 | 76.0 | 76.0 | 76.0 | 77.0 | 77.0 | 76.5 | 76.0 | 76.0 | 76.0 |

| Women (%) | 45.8 | 46.7 | 48.2 | 48.2 | 49.0 | 49.0 | 45.5 | 46.0 | 45.8 | 47.2 |

| Ratea | 116.20 | 112.20 | 116.97 | 123.57 | 120.73 | 121.04 | 114.85 | 121.34 | 119.90 | 118.57 |

| Standardised ratea,b | 94.56 | 90.78 | 93.79 | 98.12 | 91.87 | 90.78 | 85.86 | 90.30 | 87.36 | 91.45 |

| CT (%) | 88.3 | 87.5 | 88.7 | 89.5 | 89.7 | 88.7 | 88.8 | 90.8 | 90.6 | 89.1 |

| MRI (%) | 30.8 | 34.2 | 36.3 | 39.0 | 37.4 | 35.9 | 33.2 | 38.1 | 36.9 | 34.9 |

| Arteriography (%) | 3.8 | 7.1 | 11.4 | 18.5 | 20.4 | 22.9 | 21.2 | 18.2 | 18.1 | 14.1 |

| Ultrasound (%) | 36.2 | 26.0 | 25.6 | 33.6 | 40.4 | 42.0 | 44.6 | 46.1 | 46.6 | 37.2 |

| Patients aged 18-49 years | ||||||||||

| Complete episodes | 73 | 60 | 84 | 86 | 82 | 87 | 84 | 108 | 92 | 756 |

| Discharges | 75 | 64 | 88 | 97 | 94 | 93 | 95 | 122 | 105 | 833 |

| Discharges per complete episode | 1.03 | 1.07 | 1.05 | 1.13 | 1.15 | 1.07 | 1.13 | 1.13 | 1.14 | 1.10 |

| Age (years), mean | 40.6 | 40.8 | 41.8 | 41.5 | 41.3 | 40.9 | 43.5 | 43.8 | 42.1 | 41.9 |

| Age (years), median | 42.0 | 43.5 | 44.0 | 44.0 | 44.0 | 43.0 | 45.0 | 46.0 | 43.0 | 44.0 |

| Women (%) | 32.9 | 30.0 | 39.3 | 40.7 | 32.9 | 43.7 | 46.4 | 35.2 | 27.2 | 36.6 |

| Ratea | 10.24 | 8.29 | 11.46 | 11.71 | 11.20 | 11.98 | 11.71 | 15.29 | 13.23 | 11.66 |

| Standardised ratea,b | 10.71 | 8.68 | 11.87 | 11.81 | 11.30 | 11.63 | 10.99 | 14.15 | 11.82 | 11.52 |

| CT (%) | 90.4 | 88.3 | 91.7 | 95.3 | 91.5 | 83.9 | 86.9 | 89.8 | 90.2 | 88.8 |

| MRI (%) | 74.0 | 55.0 | 67.9 | 74.4 | 59.8 | 72.4 | 66.7 | 62.0 | 63.0 | 66.4 |

| Arteriography (%) | 13.7 | 13.3 | 29.8 | 41.9 | 45.1 | 47.1 | 38.1 | 38.9 | 35.9 | 32.5 |

| Ultrasound (%) | 47.9 | 23.3 | 36.9 | 29.1 | 41.5 | 54.0 | 56.0 | 46.3 | 45.7 | 43.6 |

| Patients aged ≥ 50 years | ||||||||||

| Complete episodes | 1532 | 1519 | 1594 | 1707 | 1688 | 1694 | 1605 | 1671 | 1665 | 14 675 |

| Discharges | 1565 | 1555 | 1647 | 1793 | 1784 | 1815 | 1758 | 1837 | 1840 | 15 594 |

| Discharges per complete episode | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.03 | 1.05 | 1.06 | 1.07 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.11 | 1.06 |

| Age (years), mean | 75.1 | 75.3 | 75.6 | 75.1 | 76.2 | 76.0 | 75.7 | 75.2 | 75.7 | 75.6 |

| Age (years), median | 76.0 | 77.0 | 77.0 | 77.0 | 77.0 | 78.0 | 77.0 | 77.0 | 77.0 | 77.0 |

| Women (%) | 46.4 | 47.3 | 48.7 | 48.6 | 49.8 | 49.3 | 45.4 | 46.9 | 46.9 | 47.7 |

| Ratea | 398.51 | 384.36 | 391.95 | 408.70 | 393.66 | 385.29 | 357.56 | 366.50 | 358.50 | 381.99 |

| Standardised ratea,b | 309.13 | 298.69 | 304.04 | 318.51 | 298.91 | 294.33 | 277.83 | 287.84 | 281.97 | 296.53 |

| CT (%) | 88.3 | 87.6 | 88.5 | 89.2 | 89.6 | 89.0 | 88.8 | 91.0 | 90.7 | 89.1 |

| MRI (%) | 28.8 | 33.4 | 34.6 | 37.1 | 36.3 | 33.9 | 31.3 | 36.5 | 35.4 | 33.3 |

| Arteriography (%) | 3.3 | 6.8 | 10.4 | 17.2 | 19.2 | 21.6 | 20.2 | 16.8 | 17.1 | 13.1 |

| Ultrasound (%) | 35.6 | 26.1 | 25.0 | 33.9 | 40.3 | 41.3 | 44.1 | 46.1 | 46.7 | 36.9 |

While standardised rates decreased from 208.4 episodes (2006) to 195.0 episodes per 100 000 population (2014), due to population growth, the number of episodes (care activity) remained constant. Joinpoint regression analysis (Fig. A.1 of Supplementary material) revealed a downward trend with an APC of –2.06% (P < .05); this indicates that the rate decreased by 2.06% each year. The number of ischaemic strokes increased (by 9.6% for the whole period), whereas the standardised rate increased to a lesser extent (3.2%, from 116.2 to 119.9); joinpoint regression analysis did not reveal a significant trend (APC of –1.00%; P ≥ .05). The number of TIAs decreased (by 26.0%), as did the standardised rate, which decreased from 58.2 episodes (2006) to 40.6 episodes per 100 000 population (2014). Joinpoint regression analysis identified an inflection point, which resulted in 2 periods with different trends: a first period (2006-2011) with a downward trend (APC of –9.66%; P < .05), and a second period (2012-2014) where the trend remained stable (APC of 2.05%; P ≥ .05). Lastly, episodes of haemorrhagic stroke increased by 8.1%, with a stable standardised rate (34.0-34.6 episodes per 100 000 population); no statistically significant trends were observed (APC of –0.57%; P ≥ .05).

By age, 6.4% of all episodes occurred in individuals aged 18 to 49 years; haemorrhagic stroke (12.3%) was more frequent than ischaemic stroke (4.9%) or TIA (6.0%) in this age group. A similar phenomenon was observed in standardised rates: CVD in young adults accounted for 12.9% of the total, although differences were observed between stroke subtypes (30.3% for haemorrhagic stroke, 12.6% for ischaemic stroke, and 15.5% for TIA). A mean of 180 CVD episodes were recorded per year. No changes were observed in the trend for the number of episodes or in standardised rates (from 26.7 episodes [2006] to 27.9 episodes per 100 000 population [2014]), with an APC of –0.17% (P ≥ .05) (Fig. 1). The number of ischaemic strokes increased (by 26.0% for the whole period), as did the standardised rate (29.2%, from 10.2 to 13.2); joinpoint regression analysis did not reveal a significant trend (APC of 2.74%; P ≥ .05). The number of episodes and standardised rates for TIA showed similar decreases (by 26.9% and 25.1%, respectively), with standardised rates decreasing from 7.3 to 5.5 episodes per 100 000 population. Joinpoint regression analysis identified 2 periods: 2006-2012, with a downward trend (APC of –11.95%; P < .05), and 2013-2014, with no statistically significant trend (APC of 20.31%; P ≥ .05). The number of episodes and standardised rate of haemorrhagic stroke revealed no changes (9.1 episodes per 100 000 population in 2006 and 9.2 in 2014) and a stable trend (APC of 0.14%; P ≥ .05).

Of the total number of episodes, 93.4% occurred in patients aged 50 years or older. We observed a decrease in standardised rates for all CVD and by subtype. Joinpoint regression analysis revealed statistically significant downward trends for all CVD (APC of –2.25%; P < .05), ischaemic stroke (APC of –1.24%; P < .05), and TIA (APC of –6.01%; P < .05), and no significant trend for haemorrhagic stroke (APC of –0.86%; P ≥ .05). Detailed data are presented in Table 1, Fig. 2, and Tables 1-3 of the Supplementary material.

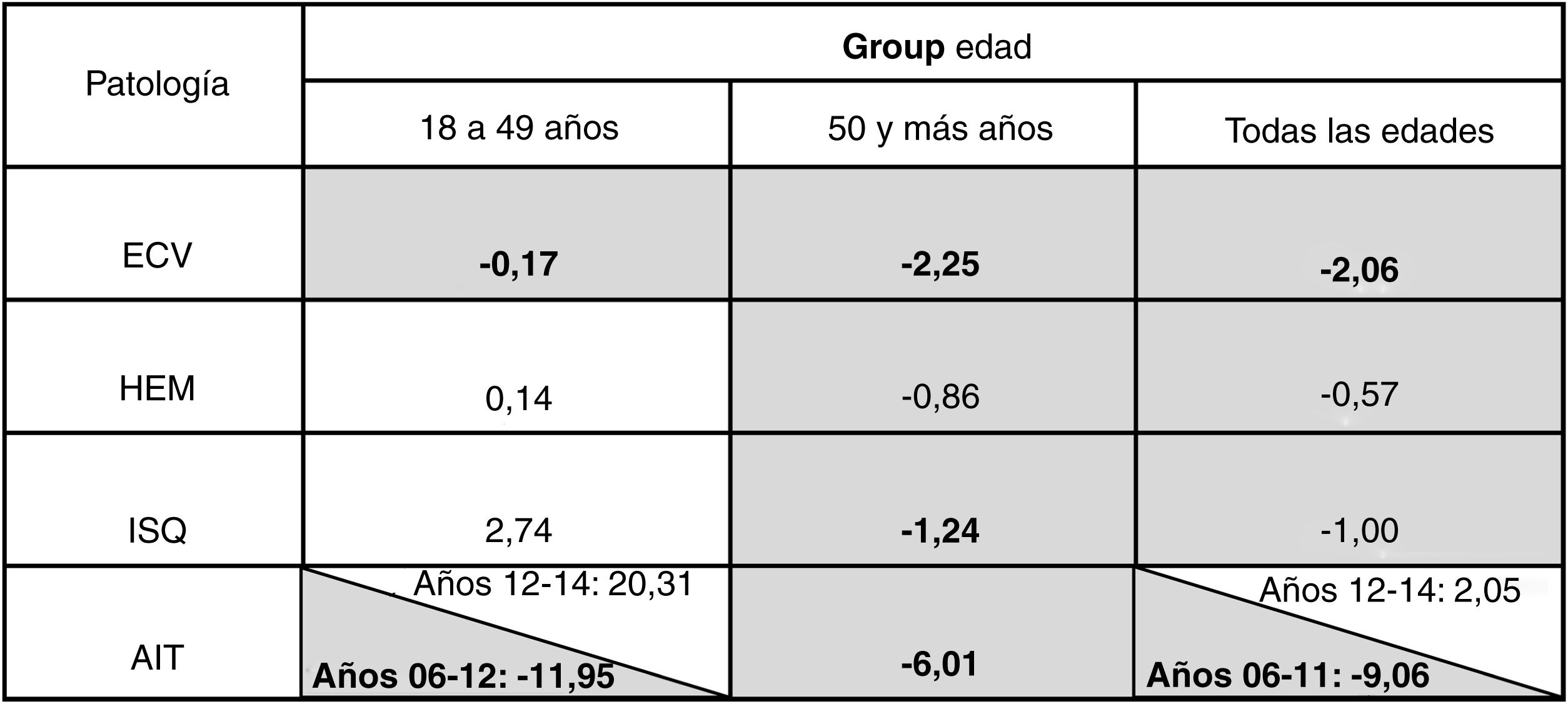

Fig. 3 summarises the results of the trends analysis. Overall, diagnostic intensity (Table 1 and Tables 1-3 of Supplementary material) was stronger among young adults; the most frequently used diagnostic technique was CT, in 85%-90% of episodes.

Average annual percentage change in the trend of cerebrovascular disease, by subtype and age (region of Murcia, 2006–2014).

Grey: negative APC. White: positive APC. Statistically significant results are shown in bold (P < .05). Statistically significant results: hospitalisation rates for all CVD, IS, and TIA in patients aged 50 years and older decreased by a mean of 2.25%, 1.24%, and 6.01%, respectively, per year. In contrast, the hospitalisation rate for TIA (2006-2012) in patients aged 18-49 years decreased by a mean of 11.95% per year, and the rates of all CVD and TIA for the total sample (2006-2011) decreased by 2.06% and 9.06%, respectively, per year.

APC: annual percentage change; CVD: cerebrovascular disease; HS: haemorrhagic stroke; IS: ischaemic stroke; TIA: transient ischaemic attack.

In this study, based on data for a 9-year period from the minimum basic dataset of the region of Murcia, we did not observe a trend in the rate of hospitalisation due to ischaemic stroke in young adults; however, we did observe a downward trend in older adults.

Our results on hospitalisation trends among young adults contradict those reported in previous studies. To our knowledge, only one study has analysed trends in hospitalisation due to ischaemic stroke in young adults in Spain10; that study provides data from the region of Extremadura over a 12-year period. The authors observed a statistically significant increase in hospitalisation rates in the group of patients aged 45 to 54 years, with an average APC of 5.7% for women and 6.7% for men, and an average APC of 6.1% for women aged 20 to 44 years. In recent years, studies conducted in Europe and the United States have also reported upward trends for incidence5,8 and hospitalisation rates.6,7,9,11–14 The most recent study, which was based on a hospital registry from the United States (National Inpatient Sample) used in the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project,13 revealed an increase in standardised rates of ischaemic stroke in patients aged 18-54 years, whereas the trend for haemorrhagic stroke remained stable, as in our study.

The difference between these results may be due to multiple factors. The Spanish IBERICTUS study15 reports geographical differences, with lower incidence of CVD in Mediterranean and central regions than in the remaining areas analysed. However, another study analysing the rate of hospital admissions due to ischaemic stroke found that the southern and Mediterranean regions of Spain presented higher rates than the national average.16 In Europe, a north-south and east-west gradient has been observed,23 with lower incidence rates in southern countries. These geographical variations may be explained by genetic and environmental factors, including differences in the distribution of cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF), local healthcare policies, and socioeconomic factors.15,16,23 For example, in the study of variations in care practice in the Spanish National Health System, while the variability of hospitalisation rates due to ischaemic stroke was low between 2005 and 2010, lower hospitalisation rates were identified in regions with low global hospitalisation rates, higher economic levels, and smaller populations around the tertiary hospital (smaller population at a distance of less than 60 minutes).16

Methodological differences between studies should also be considered. Since 2009, healthcare centres in our region have followed the Stroke Care Programme,24 according to which selected cases are transferred to stroke reference hospitals with stroke units (2 public general hospitals, of the 9 such hospitals in the region). This results in a false increase in the number of hospital discharges due to transfers between hospitals (3 transfers for every 100 discharges in 2006 and 14 transfers for every 100 discharges in 2014, in patients younger than 50 years). This could have resulted in an upward trend in our setting, but was taken into account and corrected for; however, this is not common practice in similar studies. The age ranges and ICD codes used also differ between studies. At present, there is no consensus on the definition of “young adult” in the context of CVD. Maaijwee et al.18 established an age range of 18 to 49 years, which has been used in large studies on ischaemic stroke. Lastly, to eliminate the effect of population ageing in recent years and to facilitate comparisons between populations with different age and sex distributions, we standardised hospitalisation rates using a reference population. Unlike Ramírez-Moreno et al.,10 we used the same reference population throughout the study period to obtain standardised rates, to prevent interference in our results.25

Our study is not without limitations. Due to its retrospective design and the fact that data were extracted from a clinical/administrative registry, we cannot rule out the influence of biases inherent to this type of studies. The validity of this data source depends on the information recorded at discharge and the quality of data coding; therefore, omissions and errors in diagnostic classification or coding may have affected our results. However, the registry is built with data from a single health system with homogeneous coding protocols and specialised coders; therefore, these errors are unlikely to affect temporal trends. Furthermore, our hospital has implemented the Spanish Ministry of Health’s National Health System Quality Plan to improve the quality of the registry.26 However, to minimise the influence of any possible changes in coding, we decided to analyse a shorter period of time (2006-2014), for 2 reasons. Firstly, we found more discharges with “nonspecific” diagnoses in the years before 2006; a similar phenomenon has been described at the national level.16 Secondly, data from the years following 2014 could be influenced by the change in diagnostic coding from ICD-9 to ICD-10.27 The use of clinical/administrative databases may present problems for estimating the incidence of the disease,28 as the number of cases may be underestimated; however, it is unlikely to affect the trend. In fact, the Spanish population is highly likely to seek medical attention when CVD is suspected.15 Therefore, the percentage of unrecorded cases (mild cases [most frequently TIA] not managed in hospitals and severe cases [most frequently haemorrhagic stroke] in which the patient dies before reaching hospital) is likely to be low. Furthermore, the implementation of the Stroke Care Programme of the region of Murcia in 2009,24 which involved training and the creation of regional alerts for stroke diagnosis, may at most have increased the frequency of stroke diagnosis; however, this is not seen in our results (except for patient transfers). In any case, analysis of the causes of this phenomenon is beyond the scope of the present study. The small population of the region of Murcia (approximately 1.5 million, slightly larger than that of Extremadura) and the low frequency of ischaemic stroke in young adults (1-2 cases per week) may have reduced the statistical power of our analysis. Finally, although the calculated rates were adjusted for age and sex, we were unable to adjust for other demographic and clinical characteristics that may have influenced the results (eg, increases in the use of more advanced diagnostic tools).

Although it is not the primary objective of this study, and was included to contextualise our results, the analysis of hospitalisation trends for ischaemic stroke in young adults found that they remained stable, whereas they decreased in patients older than 49 years; TIA followed a similar pattern in recent years. The decrease observed in the older population is similar to that reported in other Spanish and international studies,9,14,29–32 which may be attributed to the widespread implementation of strategies for preventing and controlling classical CVRFs.14,29,30 Although the prevalence of CVRFs has decreased in the younger Spanish population, studies have also reported a larger number of patients in whom these factors are underdiagnosed or poorly controlled,33 as well as the presence of other emerging factors in this age group.4,10 In fact, no specific guidelines have been issued for stroke prevention in young adults, and little evidence is available on the efficacy and risks associated with secondary prevention measures in this age group.17,34 The available information sources do not allow us to confirm this hypothesis; there is a need for specific studies into CVRFs in our population and to identify and implement measures to prevent modifiable CVRFs in young adults,23,33 in order to reduce the incidence and recurrence of the disease.

ConclusionsThe rate of hospitalisation due to ischaemic stroke in adults aged 18 to 49 years has remained stable over the period 2006-2014, despite the decrease among older adults. Future studies into CVD trends should be population-based (rather than single-centre data) and include more homogeneous samples to enable comparisons between regions. Given the impact of CVD on young adults, we should aim to determine the causes underlying the differences between trends in young and older adults with a view to developing strategies specifically targeting this age group.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from any public, commercial, or non-profit organisation.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We thank all the healthcare professionals who enabled us to gather the data necessary for our study.

Please cite this article as: Maldonado-Cárceles AB, Hernando-Arizaleta L, Palomar-Rodríguez JA, Morales-Ortiz A. Tendencia de la hospitalización por ictus isquémico en adultos jóvenes de la Región de Murcia durante el periodo 2006−2014. Neurología. 2022;37:524–531.