Stroke affects around 15 million people per year, with 10%-15% occurring in individuals under 50 years old (stroke in young adults). The prevalence of different vascular risk factors and healthcare strategies for stroke management vary worldwide, making the epidemiology and specific characteristics of stroke in each region an important area of research. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of different vascular risk factors and the aetiology and characteristics of ischaemic stroke in young adults in the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain.

MethodsA cross-sectional, multi-centre study was conducted by the neurology departments of all hospitals in the Aragonese Health Service. We identified all patients aged between 18 and 50 years who were admitted to any of these hospitals with a diagnosis of ischaemic stroke or TIA between January 2005 and December 2015. Data were collected on demographic variables, vascular risk factors, and type of stroke, among other variables.

ResultsDuring the study period, 786 patients between 18 and 50 years old were admitted with a diagnosis of ischaemic stroke or TIA to any hospital of Aragon, at a mean annual rate of 12.3 per 100 000 population. The median age was 45 years (IQR: 40-48 years). The most prevalent vascular risk factor was tobacco use, in 404 patients (51.4%). The majority of strokes were of undetermined cause (36.2%), followed by other causes (26.5%). The median NIHSS score was 3.5 (IQR: 2.0-7.0). In total, 211 patients (26.8%) presented TIA. Fifty-nine per cent of the patients admitted with a diagnosis of ischaemic stroke (10.3%) were treated with fibrinolysis.

ConclusionsIschaemic stroke in young adults is not uncommon in Aragon, and is of undetermined aetiology in a considerable number of cases; it is therefore necessary to implement measures to improve study of the condition, to reduce its incidence, and to prevent its recurrence.

Alrededor de 15 millones de personas sufren un ictus cada año, de los que un 10-15% ocurre en menores de 50 años (ictus en el adulto joven). La prevalencia de los distintos factores de riesgo vascular y las estrategias sanitarias para el manejo del ictus varían a nivel mundial, siendo interesante conocer la epidemiología y las características específicas de cada región. El objetivo de este estudio fue determinar la prevalencia de los diferentes factores de riesgo vascular, la etiología y las características de los ictus isquémicos en el adulto joven en la comunidad autónoma de Aragón.

MétodosEstudio multicéntrico, de corte transversal, realizado por los Servicios de Neurología de todos los hospitales del Servicio Aragonés de Salud (SALUD). Se identificó a todos los pacientes entre 18 y 50 años que ingresaron en cualquiera de estos hospitales con el diagnóstico de ictus isquémico o AIT entre enero del 2005 y diciembre del 2015. Se recogieron variables demográficas, factores de riesgo vascular y tipo de ictus isquémico entre otras.

ResultadosEn el periodo de estudio, 786 pacientes entre 18 y 50 años ingresaron con el diagnóstico de ictus isquémico o AIT en algún hospital del SALUD, con una tasa anual promedio de 12,3 por 100.000 habitantes. La mediana de su edad fue de 45 años (RIQ: 40-48 años). El factor de riesgo vascular más prevalente fue el tabaquismo, 404 (51,4%). La mayoría fue de causa indeterminada (36,2%), seguida por «otras causas» (26,5%). La mediana de puntuación en la escala NIHSS fue de 3,5 (RIQ: 2,07,0). En total, 211 (26,8%) de los ingresos fueron por AIT. De los pacientes que ingresaron con el diagnóstico de ictus isquémico, 59 (10,3%) se fibrinolizaron.

ConclusionesEl ictus isquémico en el adulto joven no es infrecuente en Aragón y en un importante número de casos es de etiología indeterminada, por lo que es necesario implementar medidas que nos permitan mejorar su estudio, disminuir su incidencia y prevenir su recurrencia.

Stroke affects around 15 million people worldwide every year, and is associated with a mortality rate of approximately 30% during the first year and severe disability in two-thirds of survivors.1,2 Nearly 80% of strokes are ischaemic, with 10%-15% occurring in individuals younger than 50 years (young adults).3 Individuals in this age group are of working age; therefore, in addition to the impact on patients and their families, mortality and disability in young adults constitute a major socioeconomic burden on society.

Mean age at stroke onset in the general population has decreased in recent years, and the incidence of stroke in young adults has increased; this trend is associated with increased prevalence of the classic vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, etc) in this age group.4 The prevalence of different vascular risk factors and healthcare strategies for stroke management vary between countries and geographical regions; we must therefore exercise caution when extrapolating data to other populations. The epidemiology and specific characteristics of stroke in each region should be considered when developing prevention and treatment strategies.5

The autonomous community of Aragon has a population of 1 325 385 (2017); each year, 2200 patients are admitted due to ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA) in the region, with stroke representing the second leading cause of death globally and the leading cause of death in women. However, the characteristics and factors associated with stroke in young adults have not been studied.

The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of different vascular risk factors and the aetiology and characteristics of ischaemic stroke in young adults (ages 18 to 50 years) in the region of Aragon between 2005 and 2015.

Material and methodsWe conducted a retrospective, observational, multicentre study, gathering data from the neurology departments of all hospitals belonging to the Health Service of Aragon. We identified all patients aged 18 to 50 years who were admitted to any hospital in the Health Service of Aragon with a diagnosis of ischaemic stroke or TIA according to the ICD-9-CM (430 to 431, 433.0A, 433.1A, 433.9A, 4340A, 434.1A, 434.9A, 436, and 437) between January 2005 and December 2015. We excluded those patients whose final diagnosis at discharge was venous sinus thrombosis; brain ischaemia secondary to head trauma, strangulation, or complications of subarachnoid haemorrhage; and any ischaemic stroke secondary to surgery, catheterisation, or angiography studies.

The following data were gathered from patients’ medical histories: demographic variables, hospital where the patient was discharged, vascular risk factors (arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, smoking, history of ischaemic stroke, history of coronary artery disease), whether the event was transient (TIA), type of ischaemic stroke according to the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project (OCSP)6 and the Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) classifications,7 National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score at admission (patients diagnosed with ischaemic stroke only), whether the patient received intravenous fibrinolysis, and whether antiplatelets or oral anticoagulants were prescribed at discharge. To analyse the distribution of vascular risk factors, stroke types, and stroke aetiology by age group, we classified our sample into 3 groups (18-30, 31-40, and 41-50 years).

We conducted a descriptive analysis, with qualitative variables expressed as frequencies and quantitative variables as measures of central tendency (mean or median) and dispersion (standard deviation [SD] or interquartile range [p25-p75]). Normality of data was tested with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

For the inferential analysis we used the chi-square test and the Fisher exact test to compare proportions for qualitative variables, and the t test or ANOVA to compare means when one of the variables was quantitative (Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normally distributed data).

Graphs were created with Microsoft Excel 2010 (v14.0) and statistical analysis was performed with SPSS (v21).

Our study protocol was approved in April 2016 by the Stroke Care Programme of the region of Aragon and the regional ethics committee.

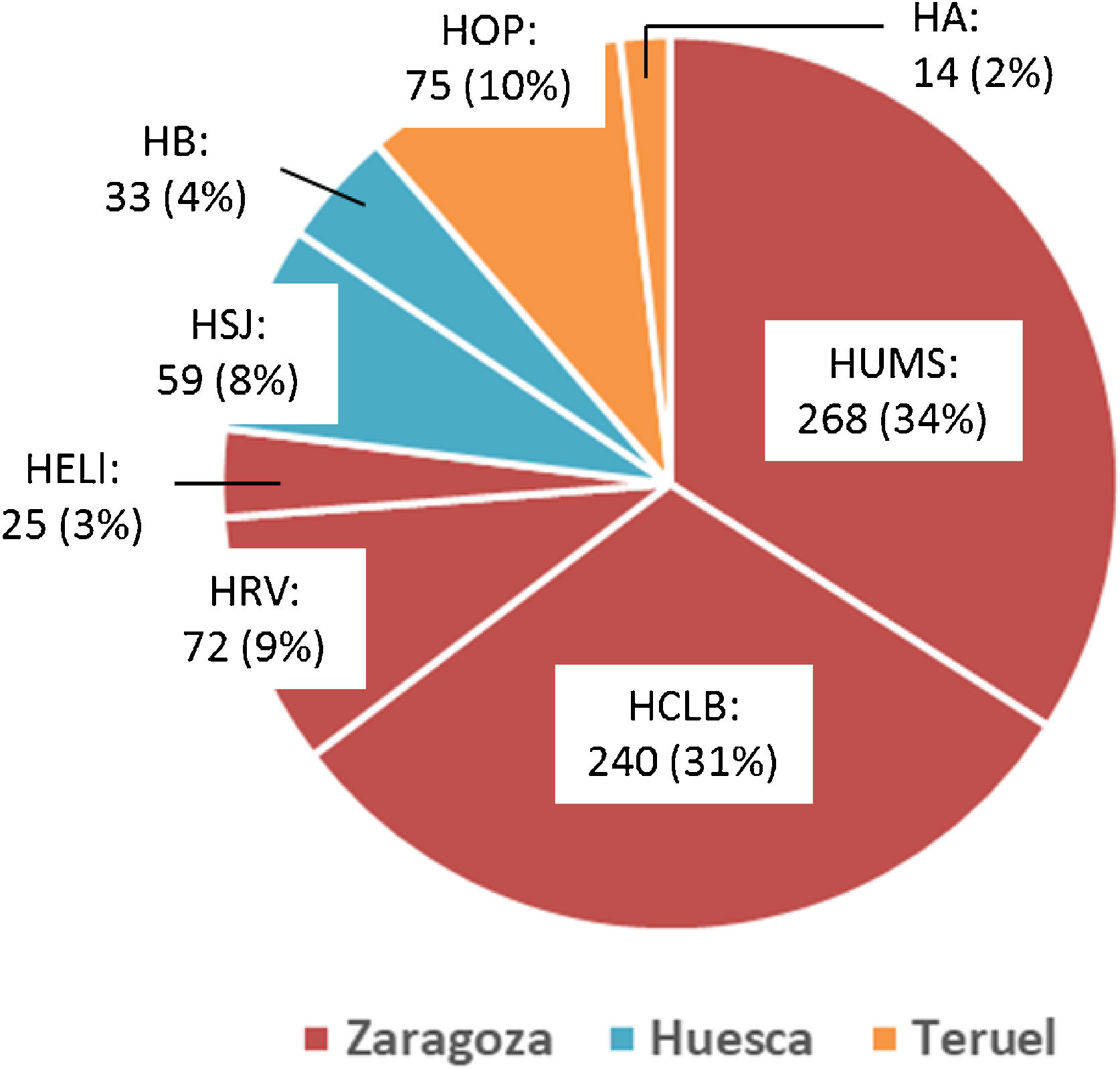

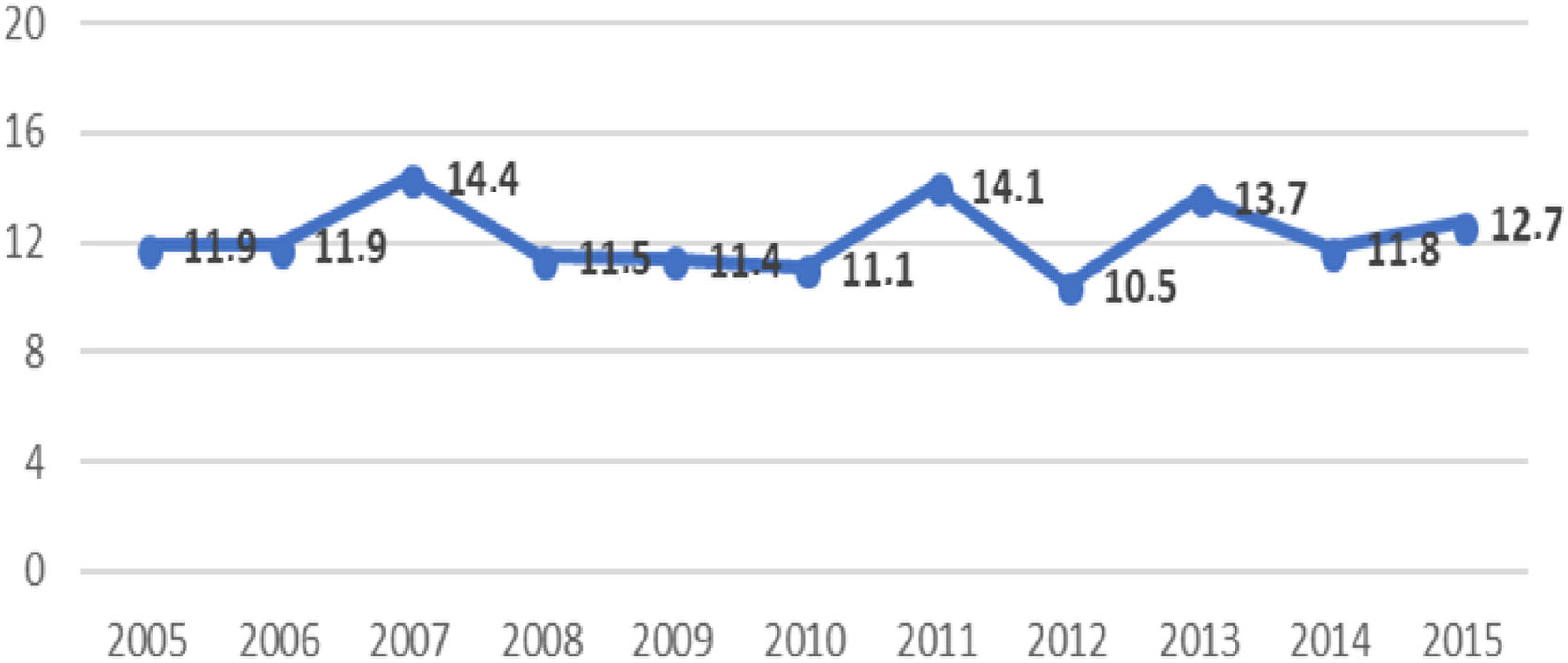

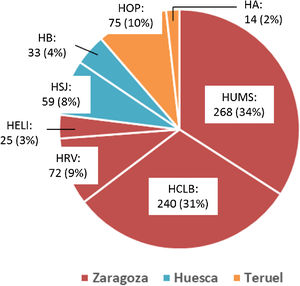

ResultsA total of 786 patients aged 18 to 50 years were admitted with a diagnosis of ischaemic stroke or TIA during the study period. Fig. 1 shows the distribution of the study population by province and by hospital; 2 were tertiary centres (Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet [HUMS] and Hospital Clínico Lozano Blesa), one has a stroke unit (HUMS), and the remaining hospitals have “stroke areas”. Fig. 2 presents the rates of hospital admission due to ischaemic stroke or TIA in patients aged 18 to 50 years per 100 000 person-years in Aragon during the study period.

Hospital admissions due to ischaemic stroke or TIA in young adults between 2005 and 2015, by province and hospital.

HA: Hospital de Alcañiz; HB: Hospital de Barbastro; HCLB: Hospital Clínico Lozano Blesa; HELl: Hospital Ernest Lluch; HOP: Hospital Obispo Polanco; HRV: Hospital Royo Villanova; HSJ: Hospital San Jorge; HUMS: Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet.

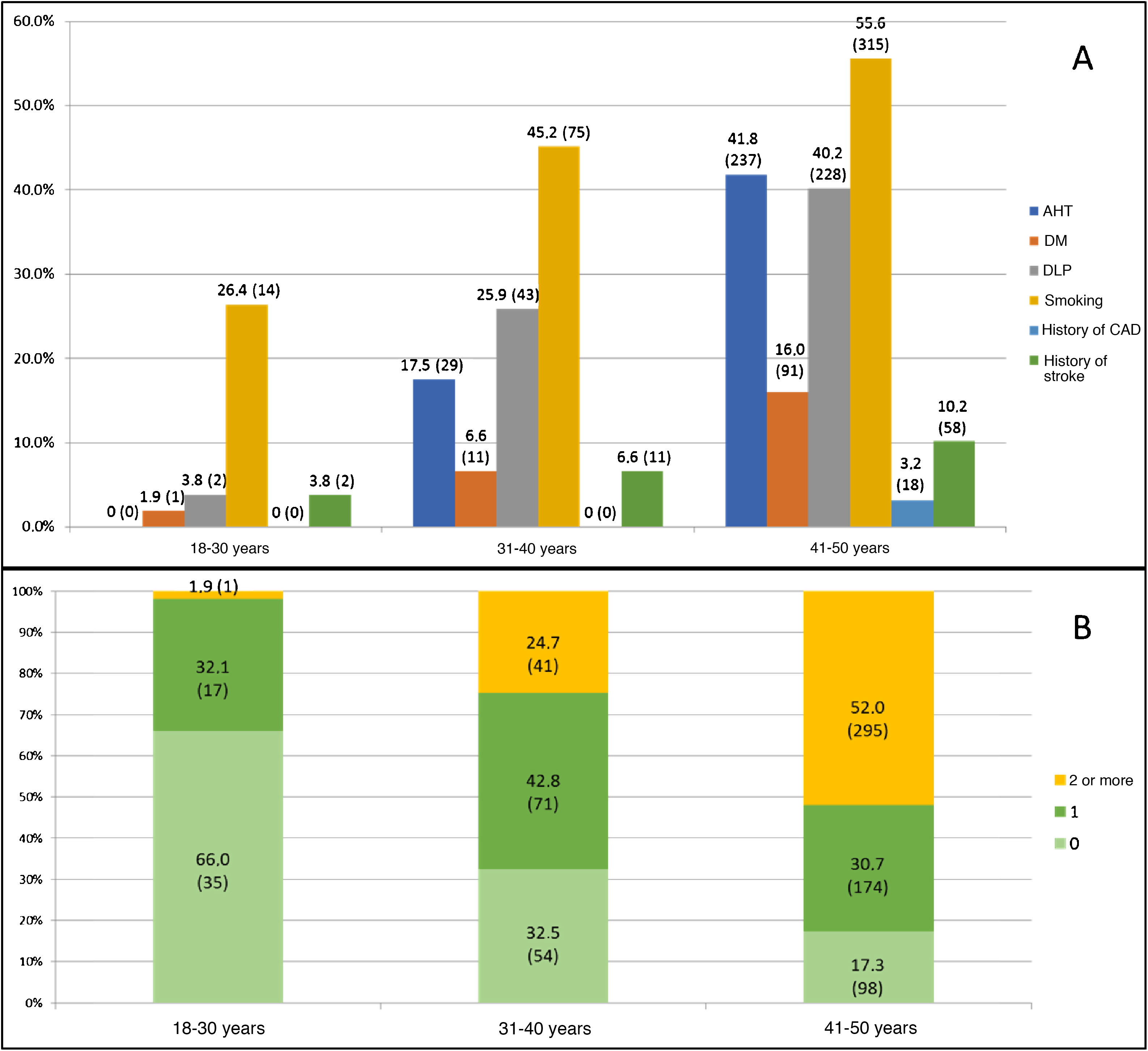

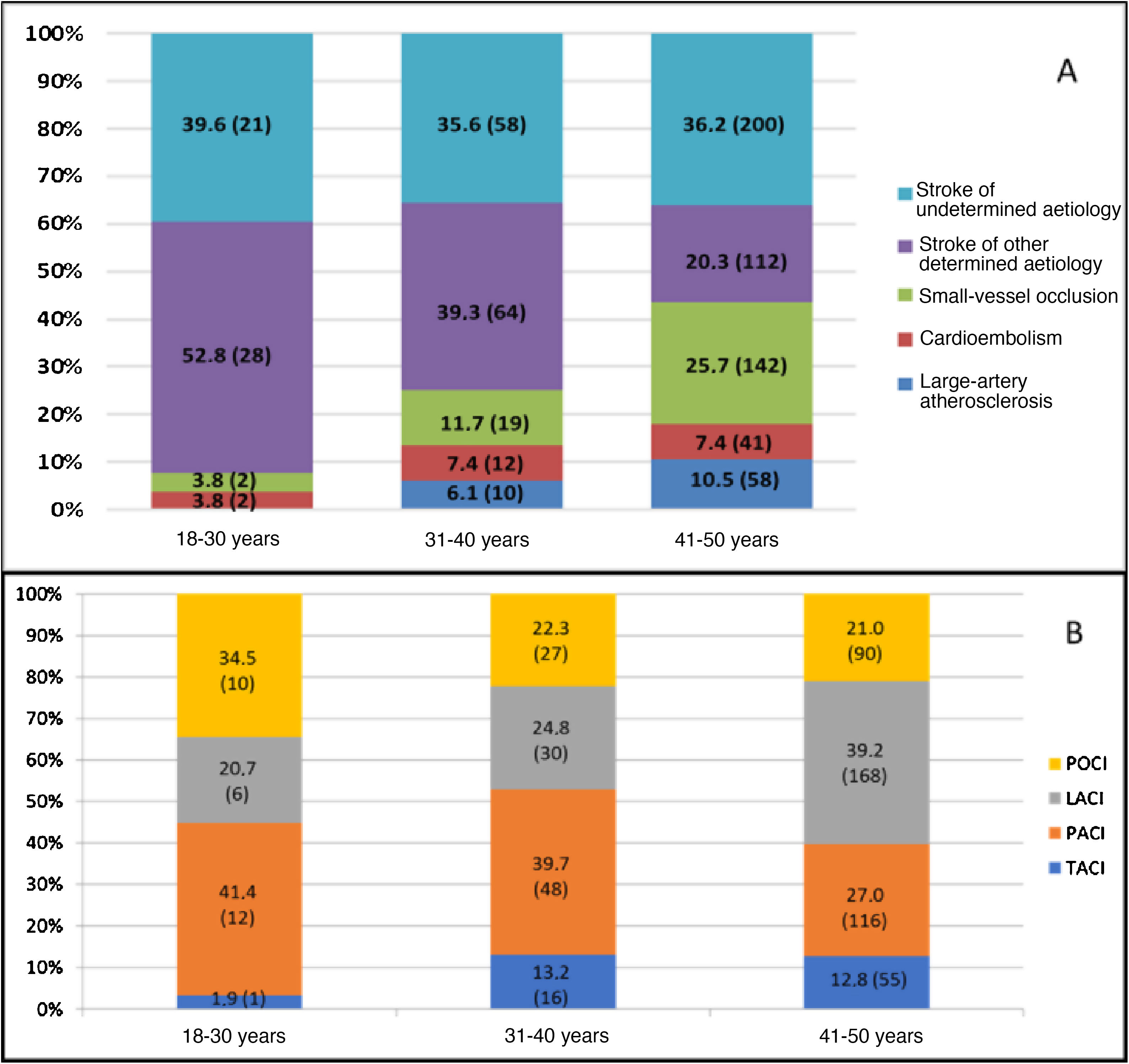

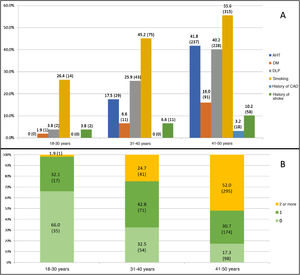

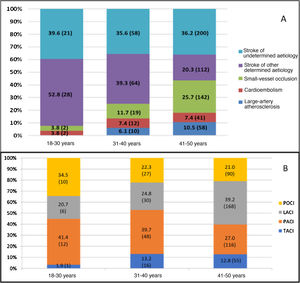

Table 1 presents our sample’s baseline characteristics, vascular risk factors, and other clinical variables. The median age in our sample was 45 years (p25-p75: 40-48); less than one-third of patients (219 patients, 27.8%) were younger than 40 years. The most prevalent vascular risk factor was smoking (404 patients, 51.4%), across all age groups (Fig. 3A); however, this was also the only vascular risk factor whose prevalence showed a statistically significant decrease over the study period. The prevalence of vascular risk factors increased in parallel with age, with over half of the patients aged 41-50 years presenting at least 2 vascular risk factors (52%, vs 19.2%; P < .001) (Fig. 3B). According to the TOAST classification, the most frequent type of stroke in our sample was stroke of undetermined aetiology (36.2%), followed by stroke of other determined aetiology (26.5%). However, as shown in Fig. 4A, frequencies vary between age groups, with stroke of other determined aetiology being the most frequent type among patients younger than 40 years. These differences are statistically significant for all stroke types except for cardioembolism and stroke of undetermined aetiology. Of the 204 cases of stroke of other determined aetiology, 98 (48.0%) were attributable to patent foramen ovale. According to the OCSP classification, the most frequent type of stroke in our sample was lacunar infarct; however, in the subgroup of patients younger than 40 years, the most frequent type was partial anterior circulation infarct (40.3% vs 27%; P = .003) (Fig. 4B). A total of 211 patients (26.8%) were admitted due to TIA. In the group of patients with non-TIA ischaemic stroke, the median NIHSS score at admission was 3.5 (p25-p75: 2.0-7.0); 54 patients (9.9%) were admitted due to severe stroke (NIHSS > 15). Of all patients admitted with a diagnosis of ischaemic stroke, 59 (10.3%) were treated with fibrinolysis and 742 (96.2%) were discharged with antithrombotic therapy (antiplatelets or anticoagulants). Twenty-four of the patients receiving fibrinolysis (40.6%) were treated at the HUMS (the only hospital in the region with a stroke unit). The province with the lowest percentage of young adults with ischaemic stroke receiving fibrinolysis was Huesca (2.9%), and the province with the highest percentage was Zaragoza (12.1%). Fibrinolysis was administered more frequently to patients aged 18-30 years (21.4%) than to patients aged 41-50 years (8.9%) (P = .03); we found no temporal trend in the percentage of patients receiving fibrinolysis per year.

Characteristics of the study population.

| N = 786 | |

|---|---|

| Median age, years (p25-p75) | 45 (40-48) |

| 18-30 | 53 (6.7%) |

| 31-40 | 166 (21.1%) |

| 41-50 | 567 (72.1%) |

| Men | 487 (62%) |

| Vascular risk factors | |

| Arterial hypertension | 266 (33.8%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 103 (13.1%) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 273 (34.7%) |

| Smoking | 404 (51.4%) |

| History of stroke | 71 (9%) |

| History of coronary artery disease | 18 (2.3%) |

| Transient ischaemic attack | 211 (26.8%) |

| Stroke type: TOAST classification 769/786 | |

| Large-artery atherosclerosis | 68 (8.8%) |

| Cardioembolism | 55 (7.2%) |

| Small-vessel disease | 163 (21.2%) |

| Stroke of other determined aetiologya | 204 (26.5%) |

| Stroke of undetermined aetiology | 279 (36.3%) |

| Stroke type: OCSP classification | |

| TACI | 72 (12.4%) |

| PACI | 176 (30.4%) |

| LACI | 204 (35.2%) |

| POCI | 127 (21.9%) |

| NIHSS > 15 | 54 (7.7%) |

| Intravenous fibrinolysis | 59 (10.3%) |

| Antiplatelets, prescribed at discharge | 660 (85.6%) |

| OAC, prescribed at discharge | 82 (10.6%) |

LACI: lacunar infarction; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; OAC: oral anticoagulants; OCSP: Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project; PACI: partial anterior circulation infarction; POCI: posterior circulation infarction; TACI: total anterior circulation infarction; TOAST: Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment.

The incidence of ischaemic stroke in young adults ranges from 3 to 13 cases per 100 000 population8–11; rates vary considerably between geographical regions. The incidence of ischaemic stroke in young adults in Aragon was 12.2 cases per 100 000 person-years, with no significant changes over the study period. Although this rate is similar to those reported by Leno et al.12 in the Spanish region of Cantabria (12 cases per 100 000 person-years), it is still high, particularly in comparison with those reported by other recent studies conducted in Helsinki, Finland and Ferrara, Italy (6.6 and 7.4 cases per 100 000 person-years, respectively).10,11 However, the populations in these 2 studies differ considerably from our own in terms of characteristics and age.

The idea that the risk factors and aetiology of ischaemic stroke in young adults differ from those observed in older adults has arisen from studies, most including patients from tertiary hospitals, that report a high prevalence of unusual causes of stroke among younger individuals.13 However, recent studies have found that the prevalence of traditional vascular risk factors is similar in young adults and in older individuals. Between 19% and 39% of young adults with ischaemic stroke have history of arterial hypertension, 17%-60% have dyslipidaemia, 2%-10% have diabetes, and 42%-57% are smokers.3,10,14–18 In all series, these prevalence rates increase significantly in line with age group, particularly in the case of arterial hypertension and, to a lesser extent, dyslipidaemia.19 This was also observed in our sample, in which the prevalence of these risk factors was within the intervals mentioned previously, with increases in the prevalence rates of arterial hypertension, smoking, and dyslipidaemia in parallel with age: only 17.3% of patients aged between 41 and 50 years did not present any of the classic vascular risk factors, and more than half (52%) presented at least 2. This is particularly relevant in the planning of prevention strategies, considering that the number of vascular risk factors is independently associated with mortality rates in young adults with ischaemic stroke.20

The most frequent type of ischaemic stroke in our sample was stroke of undetermined aetiology, in 279 patients (36.3%). This percentage includes strokes in which the cause could not be identified after a complete study, and also those cases in which the study was incomplete (52.4% of all cryptogenic strokes). Although this percentage lies within the range reported in the literature,21 it is still concerning, since correctly determining the cause of stroke is essential for secondary prevention, and young adults present a considerable risk of recurrent ischaemic stroke in the early years after the initial event (1%-3%).19 In fact, 71 patients in our sample (9%) had history of stroke. Small-vessel disease was another frequent cause of ischaemic stroke in our sample (21.2%), being most frequent in the 41-50 years age group (25.7%), where vascular risk factors are more prevalent. Of the 204 cases of stroke of other determined aetiology, 98 were secondary to patent foramen ovale (48%), which supports the high prevalence of this heart defect in stroke patients younger than 40 years. The low prevalence of atrial fibrillation in our sample (7.2%) is consistent with reports published in the literature22,23; this alteration is clearly linked to older age, with the highest prevalence rates in individuals older than 85 years.24 The same is true for the prevalence of large-artery atherosclerosis as the cause of stroke in young adults (8.8%). As we might expect, in our population the prevalence of these aetiologies of ischaemic stroke, associated with presence of vascular risk factors, increases progressively with age: in patients aged 41 to 50 years, 36.2% of all ischaemic strokes were secondary to large-artery atherosclerosis or small-vessel disease, compared to 3.8% among patients aged 18 to 30 years (P < .001).

LimitationsOur study only included patients admitted due to ischaemic stroke or TIA; we did not include patients who died during transfers, who never consulted, or who were attended on an outpatient basis. While nearly all patients with ischaemic stroke are hospitalised, regardless of symptom severity, it is common practice at our hospitals to follow a fast assessment protocol for TIA, with head CT, blood analysis, ECG, and Doppler ultrasound studies being performed at the emergency department, and complementary tests being performed on an outpatient basis when necessary (eg, ABCD2 score > 4). Therefore, TIA may be under-represented in our sample.

ConclusionIschaemic stroke in young adults is not rare in Aragon. It is associated with presence of one or more traditional vascular risk factors and is of undetermined aetiology in a considerable percentage of cases. Measures should be implemented to reduce its incidence, improve assessment, and prevent recurrence. Our study serves as a reference for evaluating the impact of such measures.

Based on the available evidence, we believe that our results may be generalised to other populations. In doing so, however, the differences in baseline characteristics between population groups should also be considered.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from any public, commercial, or non-profit organisation.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Tejada Meza H, Artal Roy J, Pérez Lázaro C, Bestué Cardiel M, Alberti González O, Tejero Juste C, et al. Epidemiología y características del ictus isquémico en el adulto joven en Aragón. Neurología. 2022;37:434–440.